Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the third most commonly diagnosed cancer, ranking second among the most common causes of cancer-related mortality. Immune checkpoint therapy has recently been shown to have great potential. However, only some patients respond to immune checkpoint blockade, indicating the unmet need for determining the underlying mechanism of colorectal cancer immunosuppression. In this study, we analyzed The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) datasets and found that high expression of PIPKIγ positively correlated with tumor-associated macrophage infiltration. Further loss-of-function studies revealed that silencing PIPKIγ greatly reduced CCL2 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, leading to weak chemotaxis of cancer cells to macrophages. Mechanistically, PIPKIγ facilitated PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway activation to increase STAT3 phosphorylation levels, thus triggering CCL2 transcription to enhance tumor-associated macrophage recruitment. These findings identify the PIPKIγ signaling pathway as a new actor in colorectal cancer immunosuppression and a potential therapeutic target for this common cancer.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive system. Currently, the incidence of colorectal cancer is ranked third among malignant tumors [1, 2]. In 2019, there were more than 130,000 new patients with colorectal cancer, and more than 50,000 people died of colorectal cancer in the United States. Worldwide, the incidence of colorectal cancer is also on the rise, which emphasizes the importance of further understanding the mechanisms of CRC initiation and progression.

Previous studies have reported that the interaction between tumor cells and the microenvironment, especially transformed cells and infiltrating immune cells, greatly supports the progression of cancer [3, 4]. Treatments such as PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade [5] and chemokine regulation have successfully altered the effects of the interaction between the immune system and cancer on rejection or, at least, have inhibited progression [6]. However, only 20%-30% of patients respond to immunological treatment [7]. Previous studies reported that cancer cells could reshape the immune microenvironment and the function of immune cells. The most important factor in this process is tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which originate mainly from monocytes that are recruited to the tumor microenvironment. TAMs could exert immunosuppressive effects by releasing cytokines/chemokines, expressing checkpoint ligands and inducing cytotoxic T cell apoptosis, leading to immunosuppression and immune evasion. These findings thus emphasize the importance of uncovering mechanisms of how cancer cells recruit and educate immune cells.

Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (PIPKIγ), encoded by PIP5K1C, is a crucial enzyme that plays a key role in multiple biological processes by regulating PI4, 5P2 synthesis [8, 9]. PIPKIγ was reported to regulate cell migration in multiple ways, such as through the EGF receptor (EGFR), upon Y639 phosphorylation by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) [10, 11]. PIPKIγ could regulate neoplastic adhesion formation at the front edge through direct interaction with talin [12]. Additionally, PIPKIγ could bind to AP2, an adaptor of E-cadherin to clathrin, to reform E-cadherin-based intercellular adhesions and restore epithelial polarization [13]. Indeed, recent work shows that upregulation of PIPKIγ expression inversely correlates with the overall survival of patients with various types of cancer [14, 15]. However, the roles of PIPKIγ in tumor immunosuppression microenvironment formation remain unclear.

In this study, we aimed to identify the relationship between PIPKIγ and the tumor immunosuppression microenvironment. By analyzing TCGA data, we found that PIPKIγ expression was positively correlated with macrophage infiltration. Mechanistically, high PIPKIγ expression in CRC cancer increased CCL2 expression by activating the AKT-STAT3 signaling axis, further facilitating macrophage infiltration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116, SW620, LOVO, and SW480 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were grown in regular DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, Gibco) or RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma using the MycoAlert mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza, Portsmouth, NH).

2.2. RNA Interference Studies

For shRNA-mediated knockdown of gene expression experiments, SW480 and LOVO cells were infected with the lentivirus of control (Ctrl), sh PIP5Iγ-1, or sh PIP5Iγ-2 for 48 h and treated with 2 μg/ml puromycin for a further one week to select the stable clones. For siRNA-mediated genes knockdown, Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was used following the protocol provided by manufacturer, and cells were used 48–72 h posttransfection. Knockdown efficiency of PIPKIγ was confirmed by Q-PCR and Western blotting analysis.

2.3. ELISA

Colorectal cancer cells with the indicated treatment were washed twice with PBS and incubated with FBS-free medium for 24 h. Then, the cell medium was collected and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and used immediately. CCL2, CCL5, and TGFβ1 ELISA kits were purchased from BD Biosciences and used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total cell protein was detected for supernatant normalization.

2.4. Luciferase Assay

293 T cells were plated at 60-70% confluence in 24-well plates and transiently transfected with 1 μg of different fragments of CCL2 promoter-connected luciferase reporter constructs together with expression plasmids for STAT3 using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). Empty pcDNA3.1 vector was used as a control. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase, which were cotransfected under the control of the SV40 early enhancer/promoter region (pSV40-RL, Promega).

2.5. Patients and Samples

Patients with CRC were from Shanghai East Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University. The study was conducted in accordance with International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai East Hospital. Patient samples for a human CRC tissue array containing 75 CRC specimens were also obtained from Shanghai East Hospital. Written informed consent was provided to all the patients before enrollment. Patients who had not received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other related antitumor therapies before surgery were enrolled in this study.

2.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis

First, paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Next, the sections were boiled in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min for antigen retrieval, followed by 3% hydrogen peroxide treatment at 37°C for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, 10% BSA was used to block the sections, and the sections were incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were as follows: PIPKIγ (1 : 200, Proteintech, 27640-1-AP), CD163 (1 : 300, Abcam, ab182422), and p-STAT3 (1 : 100, Cell Signaling Technology, #9145). Then, the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was incubated with the slides for 1 h at room temperature. The reactions were visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.7. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

SW480 and LOVO cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. Cross-linking was then quenched with 0.125 M glycine at room temperature for 5 min, and the cells were washed twice with cold PBS and then scraped and sonicated in lysis buffer for 20 min. Chromatin was centrifuged out at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatants were diluted 10-fold in dilution buffer. The supernatants were incubated with protein G magnetic beads (Millipore 16-662) and STAT3 antibody (1 : 100, Cell Signaling Technology, #9139) overnight at 4°C. The next day, the samples were washed with decreasingly stringent buffers 5 times. ChIP DNA was eluted from the beads with elution buffer for 10 min at 65°C. The supernatants were then incubated overnight with proteinase K. The DNA samples were purified using a Macherey-Nagel DNA purification kit for quantitative PCR, and the ChIP samples were diluted 1 : 20 and used as a template with Power Sybr Master Mix (ABI 4367659); DNA was amplified using a ViiA-7 Real-Time PCR system. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary .

2.8. Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. All experiments were performed with a minimum of three independent replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups. In all tests, p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Increased PIPKIγ Expression Positively Correlated with TAM Infiltration in CRC

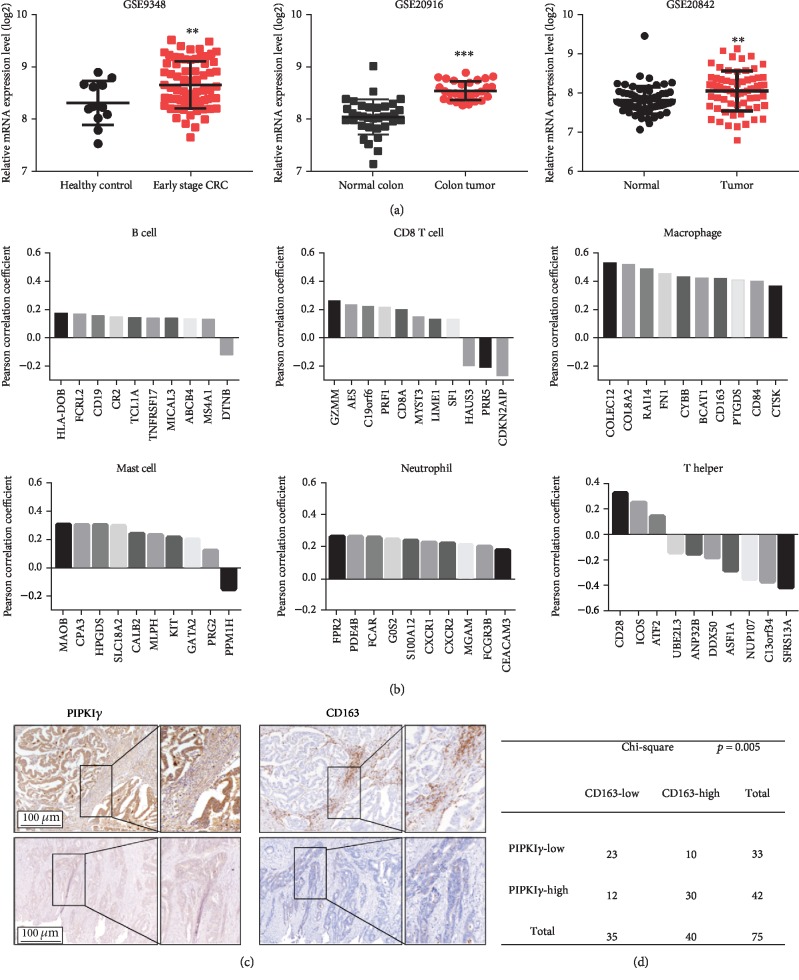

By analyzing Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets, we found that PIPKIγ expression was upregulated in CRC (Figure 1(a)). To characterize the potential immune cell components in the CRC tumor microenvironment affected by PIPKIγ, an immunome compendium was built using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data from purified immune cell subsets [16, 17]. Both innate immune cells (mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils) and acquired immune cells (B, T helper 1 (Th1) and CD8+ T), as well as cytotoxic cells, were used for investigation (Figure 1(b)). Notably, we observed that PIPKIγ was highly correlated with the gene signatures of macrophages. In contrast, no obvious correlation was found between the expression of PIPKIγ and other immune component-related genes (Figure 1(b)). To test whether PIPKIγ is associated with macrophage recruitment, immunohistochemistry was performed on CRC primary cancer serial sections. The results showed that high PIPKIγ expression samples had a stronger capacity to recruit CD163+ macrophages than their low expression counterparts, suggesting that PIPKIγ might facilitate macrophage infiltration in CRC (Figure 1(c)). Moreover, statistical analysis of this independent sample cohort also revealed a positive association between PIPKIγ expression and the number of CD163+ macrophages in CRC tissues (Figure 1(d)). Thus, PIPKIγ might exhibit a regulatory role in macrophage infiltration in CRC.

Figure 1.

Increased PIPKIγ expression positively correlated with TAM infiltration in CRC. (a) mRNA expression levels of PIP5K1C in CRC tumor tissue and corresponding nontumor tissue. (b) Correlation between PIP5K1C and specific gene signatures of B cells, CD8+ T cells, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, and T helper cells. (c) Immunohistochemical analysis of PIPKIγ expression and CD163 in a human CRC tissue microarray. Representative high and low PIPKIγ expression images are shown in the left panel, and the corresponding CD163 staining results are shown in the right panel. (d) The statistical results for PIPKIγ and CD163 tissue scores for low and high staining determined in the CRC cohort. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

3.2. Upregulated PIP5Iγ Increased CCL2 Expression in CRC Cancer Cells

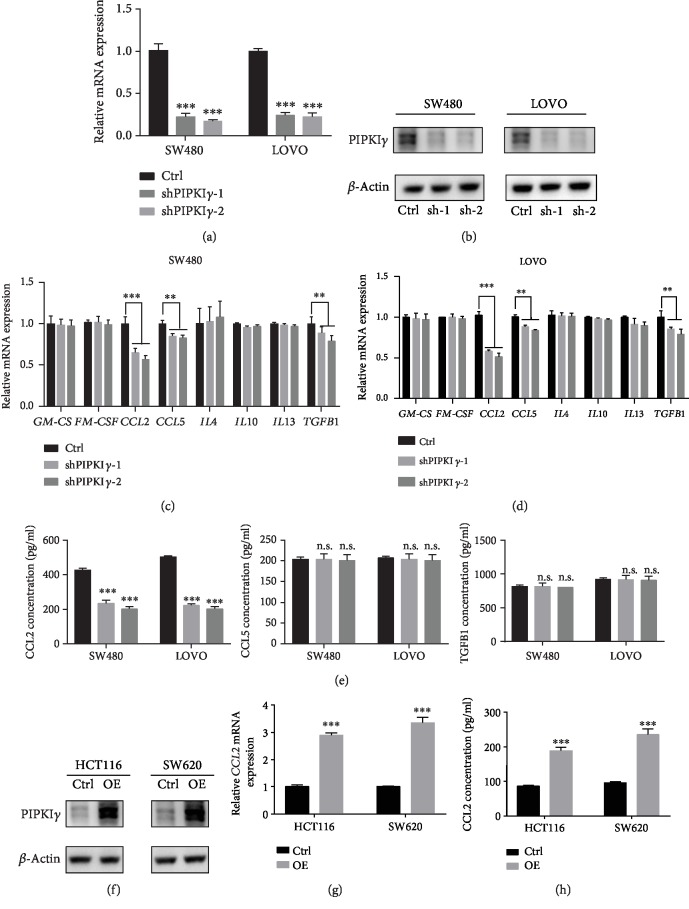

To investigate whether PIP5Iγ might enhance the recruitment of macrophages, we first examined the regulation of macrophage chemokines by PIP5Iγ. SW480 and LOVO cells, two CRC cell lines with high PIP5Iγ expression, were selected to construct stable knockdown cell lines. Q-PCR and immunoblot assays were performed to detect the efficiency of PIP5Iγ silencing. The results showed that PIP5Iγ expression was knocked down by more than 80% at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). Next, we assessed the expression of macrophage chemokines in tumor cells harboring PIP5Iγ short hairpin RNA (shRNA). Among these chemokines and cytokines, only CCL2 and CCL5 presented significantly downregulated. TGFβ1 expression present lightly changed (Figures 2(c) and 2(d)). Consistent with the qPCR analysis of macrophage-related chemokines and cytokines, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) showed that CCL2 expression was greatly decreased in both SW480 and LOVO cell lines. However, CCL5 and TGFβ1 remained almost unchanged (Figure 2(e)). To further characterize the regulation of CLL2 expression by PIP5Iγ, PIP5K1C was transfected into two low PIP5Iγ expression CRC cell lines (HCT116 and SW620) (Figure 2(f)). In agreement with the loss-of-function experiments, CCL2 expression in HCT116 and SW620 cells was remarkably increased upon PIP5K1C transfection (Figures 2(g) and 2(h)).

Figure 2.

Upregulated PIP5Iγ increased CCL2 expression in CRC cancer cells. (a) Stable shPIP5K1C-expressing SW480 and LOVO cells were grown in normal medium for 48 h, and PIP5K1C mRNA levels were measured by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT-qPCR) (n = 3, data are the mean + SD) (b) Western blot analysis of the effect of PIPKIγ knockdown in SW480 and LOVO cells. Experiments were repeated twice, and representative results are presented. (c, d) Stable shPIP5K1C-expressing SW480 and LOVO cells were grown in normal medium for 48 h, and GM-CSF, M-CSF, CCL2, CCL5, IL4, IL10, IL13, and TGFB1 mRNA levels were measured by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT-qPCR) (n = 3, data are the mean + SD). (e) Stable shPIP5K1C-expressing SW480 and LOVO cells were grown in FBS-free medium for 48 h, and ELISAs were performed to determine CCL2, CCL5, and TGFB1 levels in the CM from sh-Ctrl and sh-PIP5K1C SW480 and LOVO cells (n = 3, data are the mean + SD). (f) Western blot analysis of the effect of PIPKIγ overexpression in HCT116 and SW620 cells. Experiments were repeated twice, and representative results are presented. (g) q-PCR analysis of the mRNA level of CCL2 in PIPKIγ-overexpressing HCT116 and SW620 cells. (h) ELISA was performed to determine the protein level of CCL2 in PIPKIγ-overexpressing HCT116 and SW620 cells cultured in FBS-free medium.

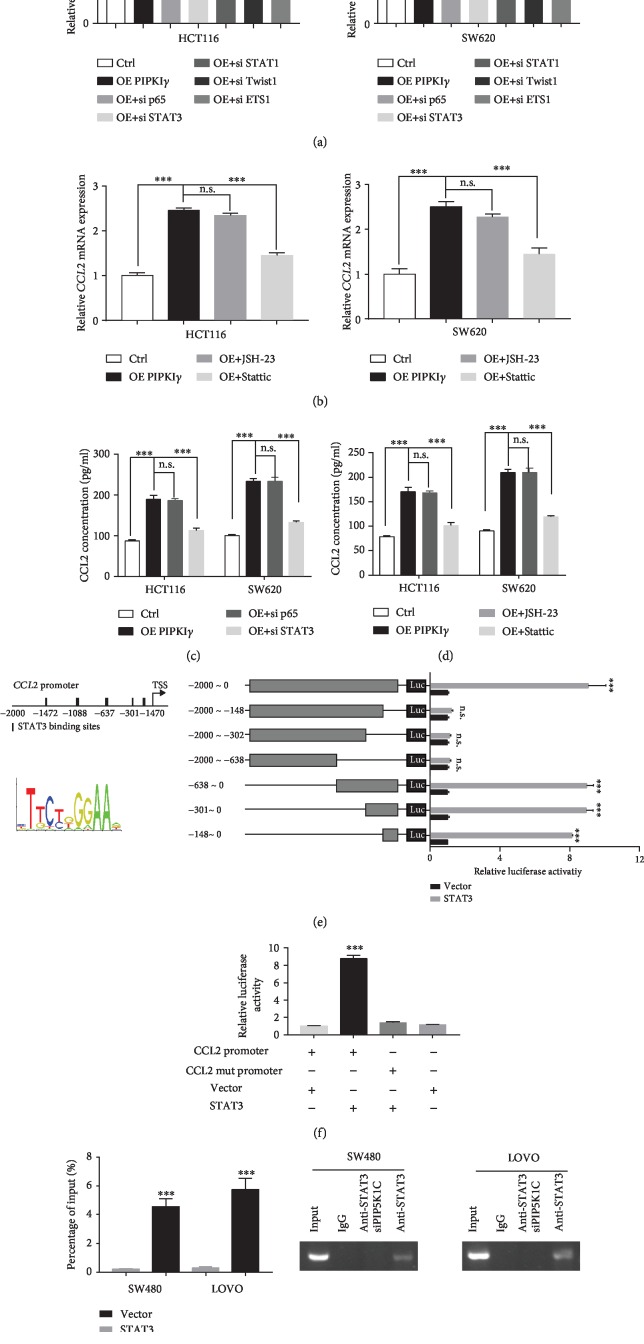

3.3. STAT3 Transcriptionally Regulates PIP5Iγ to Increase CCL2 Expression

Next, we aimed to reveal the underlying molecular mechanism through which high PIP5Iγ expression induces CCL2 upregulation. Considering that CCL2 mRNA expression increased upon ectopic expression of PIP5Iγ in CRC cells, transcription factor regulation was considered a top candidate. Previous studies reported that CCL2 could be transactivated by NF-κB, STAT3, STAT1, Twist1, and ETS1 [18–22]. Thus, we silenced these molecules in HCT116 and SW620 cells ectopically expressing PIP5Iγ. The results showed that STAT1, Twist1, and ETS1 knockdown did not considerably affect CCL2 mRNA levels. However, siRNA-induced STAT3 depletion blocked the CCL2 increase induced by PIP5Iγ (Figure 3(a)). The similar results were overserved in SW480 and LOVO (Supplementary a). In addition, the results indicated that NF-κB seems to be involved in CCL2 expression regulation. To further reveal one or both transcription factors involved in CCL2 transactivation, JSH-23 and Stattic, inhibitors of NF-κB and STAT3, were administered to PIP5Iγ-overexpressing CRC cells or high PIP5Iγ expression CRC cells. The results showed that only Stattic treatment dramatically reduced CCL2 expression, and the NF-κB inhibitor barely changed the CCL2 mRNA level (Figure 3(b) and Supplementary b). Consistently, ELISA data also implied that only STAT3 was involved in CCL2 expression regulation (Figures 3(c) and 3(d) and Supplementary c–d). To gain further evidence that CCL2 was directly transactivated by STAT3, we screened the potential binding site on the CCL2 promoter by performing a dual luciferase reporter gene assay. Among the five predicted sites, STAT3 was predominantly associated with the -147~-138 motif (Figure 3(e)), which was further confirmed by introducing mutations at this site. STAT3 transfection could not induce CCL2 upregulation after -147~-138 motif mutation (Figure 3(f)). To definitively prove that PIP5Iγ induced CCL2 expression via STAT3, CHIP-PCR was performed on PIP5Iγ-depleted SW480 and LOVO cells. As expected, CCL2 promoter binding to STAT3 was sharply reduced (Figure 3(g)). Taken together, these results suggested that STAT3 is the mediator between PIP5Iγ and CCL2.

Figure 3.

STAT3 transcriptionally regulates PIP5Iγ to increase CCL2 expression. (a) Stable PIPKIγ-expressing HCT116 and SW620 cells were transfected with siP65, siSTAT3, siSTAT1, siTwist1, or siETS1 for 48 h, and the CCL2 mRNA level was measured by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription. (b) CCL2 mRNA expression levels were detected in stable PIPKIγ-expressing HCT116 and SW620 cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. (c) Stable PIPKIγ-expressing HCT116 and SW620 cells were transfected with si p65 and siSTAT3 for 48 h, and the CCL2 protein level was measured by ELISA. (d) CCL2 protein expression levels were detected in stable PIPKIγ-expressing HCT116 and SW620 cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. (e) The predicted STAT3 binding site on the upstream 0-2000 bp and the STAT3 binding motif. HEK 293 cells were transiently cotransfected with luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3) containing the CCL2 DNA promoter region [-2000/0]) or different promoter fragment constructs, Renilla, vector, or STAT3 as indicated. After 30 h, luciferase activities were determined by dual luciferase assay. Luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activities. The values indicated represent normalized luciferase activities and are shown as the mean ± S.E. from triplicate assays. (f) Luciferase assay for HEK 293 cells transiently cotransfected with luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3) containing the CCL2 DNA promoter region [-2000/0]) or motif mutant constructs, Renilla, vector, or STAT3 as indicated. (g) ChIP-PCR analysis of STAT3 binding to the CCL2 promoter in the presence or absence of PIPKIγ silencing in SW480 and LOVO cells.

3.4. AKT Activation by PIPKIγ Mediated STAT3 Phosphorylation and CCL2 Expression in CRC

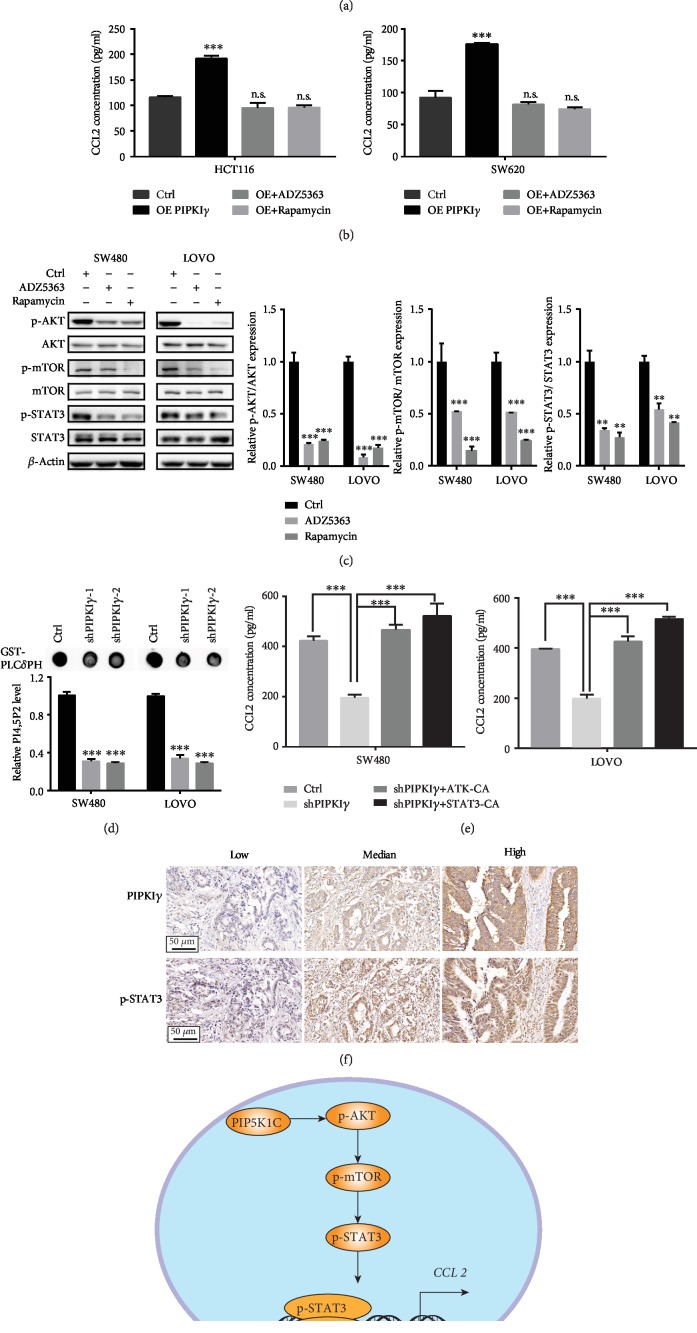

Next, we aimed to elucidate the signaling pathway between PIPKIγ and STAT3. Considering that PIPKIγ functions as a crucial substrate of the PI3K/AKT pathway, we hypothesized that AKT might mediate the response to PIPKIγ and induce STAT3 phosphorylation. To verify this hypothesis, a specific inhibitor of AKT, ADZ5363, and a specific inhibitor of mTOR, rapamycin, were administered to PIPKIγ-overexpressing HCT116 and SW620 cells as well as SW480 and LOVO cells. The results showed that AKT and mTOR inhibition significantly blocked the increase in CCL2 induced by PIPKIγ overexpression (Figure 4(a) and Supplementary ), which was further confirmed by ELISA (Figure 4(b) and Supplementary ). To further confirm the necessity of the AKT-mTOR pathway in the interaction between PIPKIγ and STAT3, AKT and mTOR inhibitors were used to treat SW480 and LOVO cells. The phosphorylation levels of STAT3, AKT, and mTOR were detected in SW480 and LOVO cells upon ADZ5363 or rapamycin treatment. We noticed that the phosphorylation level of STAT3 was markedly reduced after AKT or mTOR suppression (Figure 4(c)). Considering that PIP2 is predominantly product of PIPKIγ and the precursor compound of PIP3, we measured the level of PIP2 and PIP3 in PIPKIγ-deficient CRC cells by protein-lipid overlay assay [23]. We observed that the level of PIP2 and PIP3 were significantly decreased in PIPKIγ knockdown cells (Figure 4(d) and Supplementary ). This indicates that PIP2 generated by PIPKIγ is associated with PIP3 synthesis, resulting in PI3K/Akt activation. Next, to prove that AKT and STAT3 are indeed involved in the PIPKIγ-induced CCL2 increase, continuously activated AKT and STAT3 were transfected into PIPKIγ-depleted SW480 and LOVO cells. The results indicated that both AKT and STAT3 could rescue the reduction in CCL2 (Figure 4(e) and Supplementary ). Additionally, PIPKIγ expression and p-STAT3 expression in CRC clinical samples were positively associated (Figure 4(f)). Collectively, these results suggested that PIPKIγ may activate the PI3K-Akt-STAT3 signaling pathway, which can further increase CCL2 levels in colorectal cancer (Figure 4(g)).

Figure 4.

AKT activation by PIPKIγ mediated STAT3 phosphorylation and CCL2 expression in CRC. (a) q-PCR analysis of CCL2 mRNA levels in HCT116 and SW620 cells overexpressing PIPKIγ or not and treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. (b) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in HCT116 and SW480 cells overexpressing PIPKIγ or not and treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin in FBS-free medium. (c) Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation levels of AKT, mTOR, and STAT3 in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. Densitometric analysis presented in the right plane. Experiments were repeated twice; representative results are presented. (d) PIP2 level in the control, shPIPKIγ1, and shPIPKIγ2 cells was examined by a protein-lipid overlay assay. (e) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in PIPKIγ-depleted SW480 and LOVO cells transfected with continuously activated AKT or STAT3 plasmid. (f) Immunohistochemical analysis of PIPKIγ and p-STAT3 expression in a human Renji CRC tissue microarray. Representative low, median, and high PIPKIγ expression images are shown in the upper panel, and the corresponding samples' p-STAT3 expression levels are shown in the lower panel. (g) Proposed mechanism of PIPKIγ-AKT-mTOR-STAT3-driven CCL2 expression in colorectal cancer cells.

4. Discussion

Although early detection and overall survival have improved, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Current treatment paradigms, including chemotherapy and biologics, appear to have hit their bottleneck. Immunotherapy, especially checkpoint inhibitors, has shown considerable clinical benefits in a variety of cancers, including CRC. However, previous studies reported that only some patients respond to checkpoint inhibitors [24, 25], emphasizing the importance of further understanding the mechanism of immunosuppression microenvironment formation. In this study, we found that PIPKIγ expression positively correlated with macrophage infiltration in colorectal cancer. Further studies revealed that high expression PIPKIγ could induce the AKT-mTOR pathway, leading to increased STAT3 phosphorylation and ultimately promoting CCL2 expression.

PIPKIγ functions mainly as a phosphoinositide-producing enzyme and is highly involved in phosphoinositide metabolism. Upregulation of PIPKIγ expression is often reported in human primary tumors. We have previously shown that PIPKIγ is upregulated in pancreatic cancer cell lines, indicating the pathogenic role of PIPKIγ in malignant transformation [15]. Additionally, pY639-PIPKIγ is significantly increased in invasive ductal carcinoma, suggesting the importance of PIPKIγ in tumor progression [26]. Through the generation of PI(4,5)P2, PIPKIγ is critically important in a variety of biological processes, such as focal adhesion assembly [27, 28], ciliogenesis [29], centriole duplication [30], and leukocyte recruitment [31]. Notably, PIPKIγ is also widely implicated in many oncogenic phenotypes, such as cell proliferation [10, 23], migration [32], invasion [26], and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [11]. Analysis of TCGA cohorts showed that increased PIPKIγ expression levels positively correlated with increased macrophage infiltration, indicating that PIPKIγ might act as a new modulator of the immunosuppression environment in colorectal cancer. By both gain- and loss-of-function studies, we confirmed that PIPKIγ could significantly regulate CCL2 at both the mRNA and protein levels. However, PIPKIγ had no significant impact on other monocyte-recruited cytokines or macrophage-induced cytokines. The effect of other immune cell-related cytokines should be further studied.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathways are often activated in human cancers [33]. These pathways are initiated by the generation of PI [3–5] P3 via the PI3K-mediated phosphorylation of PI [4, 5] P2. Previously, Thapa et al. clearly demonstrated the mechanism by which PIPKIγ couples with PI3K to activate PI3K/Akt signaling [23]. In line with this, our results showed that the inhibition of p-Akt and downstream p-mTOR blocks PIPKIγ-induced STAT3 phosphorylation. Notably, PI3K/Akt signaling and the downstream mTORC1 complex are crucial regulators of STAT3 [34, 35]. In breast cancer, the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway plays a crucial role in cancer stem-like cell viability and stem maintenance [36]. In leukemia, blocking AKT-mTOR-STAT3 signaling through glycyrrhizic acid could remarkably inhibit leukemia cell migration and invasion [37]. Our data showed that high PIPKIγ expression induced AKT-mTOR-STAT3 signaling, leading to increased CCL2 transcription and immunosuppression microenvironment formation. Previous research has reported that STAT1, Twist1, ETS1, and NF-κB are also involved in CCL2 transcription [18]. In our experiment, CCL2 mRNA and protein levels were decreased in only STAT3-disrupted CRC. Similarly, the regulation of CCL2 by STAT3 was also reported in prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts [20, 38].

The infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) has been linked to tumor progression in many tumor diseases, suggesting the potential of TAM-targeting therapy for the treatment of advanced cancer [39]. It has been shown that TAMs can provide growth and survival factors, induce angiogenesis [40, 41], and enhance matrix remodeling [42] in the tumor microenvironment, consequently leading to tumor metastases. On the other hand, TAMs are a major component of immunosuppressive cells in almost all types of tumors. TAMs express molecular inducers of checkpoint proteins that inhibit T cell activation. TAMs promote the immunosuppressive activity of regulatory T (Treg) cells via bidirectional interactions, which are mediated by immunosuppressive cytokines, including IL-10 and TGFβ. Moreover, many essential amino acids are consumed by TAMs, resulting in the metabolic starvation of T cells.

CCL2, also known as MCP1, binds to CCR2 and mediates LY6Chi monocyte recruitment [43]. However, the precise mechanism by which CCL2 recruit monocytes/macrophages remains unclear. One potential mechanism is that circulating CCL2 associates with glycosaminoglycans in specific tissues and establishes gradients that guide monocytes towards these sites [44]. There is sufficient evidence that CCL2 recruits monocytes and macrophages in the tumor microenvironment [45–47]. CCL2 is highly expressed in malignant tumor cells and may play an essential role in TAM recruitment [48, 49]. After recruitment, TAMs can also produce CCL2, suggesting that a positive feedback loop may exist in the crosstalk between cancer cells and TAMs. In addition, CCL5 is another typical chemokine that recruits monocytes. In our study, we found that its mRNA expression, but not its protein expression, fluctuated after disrupting PIPKIγ expression. Considering that CCL5 has been reported to coordinate with the β-catenin/Slug pathway to promote CRC epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [50], we speculated that CRC cells may operate via another compensatory pathway to promote CCL5 translation. Besides, Chun et al. reported that CCL2 fostered MDSC accumulation in evolving colonic tumors and enhanced polymorphonuclear- (PMN-) MDSC immunosuppressive features, leading to the progression of colorectal cancer [51]. Thus, CCL2 may also promote other immune suppression cell functions, which may require more effort.

Collectively, our observations revealed that high PIPKIγ expression in tumor cells could induce AKT-mTOR signaling activation. Increased activation of AKT-mTOR increases the phosphorylation levels of STAT3, leading to CCL2 expression and suppressing cancer immune reaction activation. These findings lay the theoretical foundation for targeting PIPKIγ for the treatment of colorectal cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Excellent Young Doctor Training Program of Shanghai Pudong New Area (PWRq2014–30), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (22120180331), the Outstanding Clinical Discipline Project of Shanghai Pudong (PWYgy2018-02), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81702360).

Data Availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: (a) SW480 and LOVO cells were transfected with siP65, siSTAT3, siSTAT1, siTwist1, or siETS1 for 48 h, and the CCL2 mRNA level was measured by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription. (b) CCL2 mRNA expression levels were detected in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. (c) S SW480 and LOVO cells were transfected with si p65 and siSTAT3 for 48 h, and the CCL2 protein level was measured by ELISA. (d) CCL2 protein expression levels were detected in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. Supplementary Figure 2: (a) q-PCR analysis of CCL2 mRNA levels in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. (b) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in H SW480 and LOVO cells treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin in FBS-free medium. (c) PIP3 level in the control, shPIPKIγ1, and shPIPKIγ2 cells was examined by a protein-lipid overlay assay. (d) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in HCT116 and SW620 transfected with continuously activated AKT or STAT3 plasmid.

Supplementary Material Table 1 is “Q-PCR primers used in this study”.

References

- 1.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds P. D., Best L., George S., et al. Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a systematic review. The Lancet. 2000;356(9234, article S0140673600027136):968–974. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West N. R., McCuaig S., Franchini F., Powrie F. Emerging cytokine networks in colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2015;15(10, article BFnri3896):615–629. doi: 10.1038/nri3896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aras S., Zaidi M. R. TAMeless traitors: macrophages in cancer progression and metastasis. British Journal of Cancer. 2017;117(11, article BFbjc2017356):1583–1591. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen R., Hain E., Buhard O., et al. Association of primary resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer with misdiagnosis of microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency status. JAMA Oncology. 2018;5(4):p. 551. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topalian S. L., Drake C. G., Pardoll D. M. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4, article S1535610815000896):450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh P. P., Sharma P. K., Krishnan G., Lockhart A. C. Immune checkpoints and immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology Report. 2015;3, article gov053:289–297. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heck J. N., Mellman D. L., Ling K., et al. A conspicuous connection: structure defines function for the phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase family. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2007;42(1):15–39. doi: 10.1080/10409230601162752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xue J., Chen C., Qi M., et al. Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase regulates PD-L1 expression by activating NF-κB. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26, article 17123):42414–42427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H., Xiao N., Wang Y., et al. Smurf1 regulates lung cancer cell growth and migration through interaction with and ubiquitination of PIPKIγ. Oncogene. 2017;36(41, article BFonc2017166):5668–5680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thapa N., Tan X., Choi S., Wise T., Anderson R. A. PIPKIγ and talin couple phosphoinositide and adhesion signaling to control the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2017;36(7, article BFonc2016267):899–911. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L., Kolodziej T., Jafari N., et al. Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation regulates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type I γ 90 activity and cell invasion. The FASEB Journal. 2019;33(1):631–642. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800296R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahlfeldt N., Vahedi-Faridi A., Koo S. J., et al. Molecular basis for association of PIPKIγ-p90 with clathrin adaptor AP-2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(4):2734–2749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y., Turbin D. A., Ling K., et al. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates invasion and proliferation and its expression correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2010;12(1):p. R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C., Wang X., Fang J., et al. EGFR-induced phosphorylation of type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase promotes pancreatic cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26, article 16730):42621–42637. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Tosolini M., et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4, article S1074761313004378):782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charoentong P., Finotello F., Angelova M., et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Reports. 2017;18(1, article S2211124716317090):248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Low-Marchelli J. M., Ardi V. C., Vizcarra E. A., van Rooijen N., Quigley J. P., Yang J. Twist1 induces CCL2 and recruits macrophages to promote angiogenesis. Cancer Research. 2013;73(2):662–671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fantuzzi L., Spadaro F., Purificato C., et al. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C activation is required for CCR5-dependent, NF-κB-driven CCL2 secretion elicited in response to HIV-1 gp120 in human primary macrophages. Blood. 2008;111(7):3355–3363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X., Lin Y., Shi Y., et al. FAP promotes immunosuppression by cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment via STAT3-CCL2 signaling. Cancer Research. 2016;76(14):4124–4135. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An S. Y., Youn G. S., Kim H., Choi S. Y., Park J. Celastrol suppresses expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines by inhibiting JNK-STAT1/NF-κB activation in poly(I:C)-stimulated astrocytes. BMB Reports. 2017;50(1):25–30. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamatovic S. M., Keep R. F., Mostarica-Stojkovic M., Andjelkovic A. V. CCL2 regulates angiogenesis via activation of Ets-1 transcription factor. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(4):2651–2661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thapa N., Choi S., Tan X., Wise T., Anderson R. A. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate 5-kinase Iγ and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling couple to promote oncogenic growth. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290(30):18843–18854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.596742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao Y. P., Freeman G. J. The microsatellite instable subset of colorectal cancer is a particularly good candidate for checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Cancer Discovery. 2015;5(1):16–18. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le D. T., Uram J. N., Wang H., et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C., Wang X., Xiong X., et al. Targeting type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase inhibits breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2015;34(35, article BFonc2014393):4635–4646. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ling K., Doughman R. L., Firestone A. J., Bunce M. W., Anderson R. A. Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature. 2002;420(6911, article BFnature01082):89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nader G. P. F., Ezratty E. J., Gundersen G. G. FAK, talin and PIPKIγ regulate endocytosed integrin activation to polarize focal adhesion assembly. Nature Cell Biology. 2016;18(5, article BFncb3333):491–503. doi: 10.1038/ncb3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Q. W., Zhang Y. X., Wei Q., Huang Y., Hu J. H., Ling K. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase PIPKIγ and phosphatase INPP5E coordinate initiation of ciliogenesis. Nature Communications. 2016;7(1, article BFncomms10777) doi: 10.1038/ncomms10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Q. W., Zhang Y. X., Xiong X. H., et al. PIPKIγ targets to the centrosome and restrains centriole duplication. Journal of Cell Science. 2014;127(6):1293–1305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.141465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stadtmann A., Block H., Volmering S., et al. Cross-talk between Shp1 and PIPKIγ controls leukocyte recruitment. Journal of Immunology. 2015;195(3):1152–1161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi S., Thapa N., Hedman A. C., Li Z. G., Sacks D. B., Anderson R. A. IQGAP1 is a novel phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate effector in regulation of directional cell migration. The EMBO Journal. 2013;32(19):2617–2630. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu P., Cheng H., Roberts T. M., Zhao J. J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2009;8(8, article BFnrd2926):627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bromberg J. F., Wrzeszczynska M. H., Devgan G., et al. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98(3, article S0092867400819595):295–303. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cairns R. A., Harris I. S., Mak T. W. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11(2, article BFnrc2981):85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou J., Wulfkuhle J., Zhang H., et al. Activation of the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway in breast cancer stem-like cells is required for viability and maintenance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(41):16158–16163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702596104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He S. Q., Gao M., Fu Y. F., Zhang Y. N. Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits leukemia cell growth and migration via blocking AKT/mTOR/STAT3 signaling. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2015;8:5175–5181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin T. H., Izumi K., Lee S. O., Lin W. J., Yeh S., Chang C. Anti-androgen receptor ASC-J9 versus anti-androgens MDV3100 (enzalutamide) or Casodex (bicalutamide) leads to opposite effects on prostate cancer metastasis via differential modulation of macrophage infiltration and STAT3-CCL2 signaling. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4(8, article e764) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawa-Wejksza K., Kandefer-Szerszen M. Tumor-associated macrophages as target for antitumor therapy. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2018;66(2, article 480):97–111. doi: 10.1007/s00005-017-0480-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu C., Kros J. M., Cheng C., Mustafa D. The contribution of tumor-associated macrophages in glioma neo-angiogenesis and implications for anti-angiogenic strategies. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19(11):1435–1446. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riabov V., Gudima A., Wang N., Mickley A., Orekhov A., Kzhyshkowska J. Role of tumor associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2014;5:p. 75. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afik R., Zigmond E., Vugman M., et al. Tumor macrophages are pivotal constructors of tumor collagenous matrix. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2016;213(11):2315–2331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsou C. L., Peters W., Si Y., et al. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(4):902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Proudfoot A. E., Handel T. M., Johnson Z., et al. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(4):1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee H. W., Choi H. J., Ha S. J., Lee K. T., Kwon Y. G. Recruitment of monocytes/macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1835;2013:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook J., Hagemann T. Tumour-associated macrophages and cancer. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2013;13(4, article S1471489213000775):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollard J. W. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9(4, article BFnri2528):259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakatsumi H., Matsumoto M., Nakayama K. I. Noncanonical pathway for regulation of CCL2 expression by an mTORC1-FOXK1 axis promotes recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Reports. 2017;21(9, article S2211124717316340):2471–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X. G., Yao W. B., Yuan Y., et al. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66(1):157–167. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen K., Liu Q., Tsang L. L., et al. Human MSCs promotes colorectal cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition and progression via CCL5/β-catenin/Slug pathway. Cell Death & Disease. 2017;8(5, article e2819) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chun E., Lavoie S., Michaud M., et al. CCL2 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by enhancing polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell population and function. Cell Reports. 2015;12(2, article S2211124715006221):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: (a) SW480 and LOVO cells were transfected with siP65, siSTAT3, siSTAT1, siTwist1, or siETS1 for 48 h, and the CCL2 mRNA level was measured by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription. (b) CCL2 mRNA expression levels were detected in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. (c) S SW480 and LOVO cells were transfected with si p65 and siSTAT3 for 48 h, and the CCL2 protein level was measured by ELISA. (d) CCL2 protein expression levels were detected in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with JSH-23 and Stattic in FBS-free medium. Supplementary Figure 2: (a) q-PCR analysis of CCL2 mRNA levels in SW480 and LOVO cells treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. (b) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in H SW480 and LOVO cells treated with the AKT inhibitor ADZ5363 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin in FBS-free medium. (c) PIP3 level in the control, shPIPKIγ1, and shPIPKIγ2 cells was examined by a protein-lipid overlay assay. (d) ELISA analysis of CCL2 protein levels in HCT116 and SW620 transfected with continuously activated AKT or STAT3 plasmid.

Supplementary Material Table 1 is “Q-PCR primers used in this study”.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.