Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine whether the tooth crown sexual dimorphism pattern reported in previous small studies can be generalized for a broader range of populations.

Literature review

A systematic literature review was performed by two independent examiners. The following databases were searched from October 2015 to July 2016: PubMed, Scopus, Lilacs, ScienceDirect, Medline, and Cochrane Reviews. No language restrictions were applied to the search.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised original studies investigating mesiodistal permanent teeth that reported the sample population and standard deviation. All right-sided teeth, except the third molars, were measured and separated by sex in the included studies. Thirty-one studies were included in the quantitative data synthesis and meta-analysis. Studies of non-human teeth, skeletal remains, or an overly specific study population were excluded.

Main results

Thirty-one trials, involving 6481 participants, provided data for the meta-analysis of teeth. Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal crowns was found in all teeth across a range of populations, principally in lower canines (5.73%) and maxillary canines (4.72%), followed by the lower second molars (3.54%) and upper second molars(3.20%), and finally in the lower first molars(3.14%) and upper first molars(2.64%).

Conclusions

A small degree of sexual dimorphism exists in all human teeth. Second molars and canines show the greatest sexual dimorphism. Additionally, smaller racial differences are present in mesiodistal crowns among groups living in different geographic areas; however, it is not possible to establish a single value applicable for all populations.

KEYWORDS : Forensic Dentistry, Odontometry, Sexual Dimorphism, Tooth Crown, Permanent dentition, Crown dimension

Introduction

Dental anatomy is an important factor in establishing an accurate diagnosis, and can be used in the assessment of treatment and control cases. (1) Dental crown dimensions and root dimensions are important in determining appropriate treatment (2) and achieving greater stability in orthodontic planning. (3) Dental parameters are also used for the identification of human remains by anthropologists, biologists, and forensic experts; such parameters enable post-mortem determination of sex and age, as teeth may be more likely to remain intact when other bony structures are destroyed. (4, 5)

Within this context, human dentition and crown size are considered a useful aid in determining a subject's sex; most teeth are fully developed before skeletal maturation, and are thus valuable sex indicators. (6)

The two most commonly used measures of the tooth crown are mesiodistal and buccolingual diameters (7, 8) notably, other measures have been developed: trigonid mesiodistal, trigonid buccolingual, talonid mesiodistal, and talonid buccolingual diameters. (9) Moreover, there are more sophisticated methods to measure the dental crown, as well as the whole tooth, with reduced discrepancy. (10, 11) Prior studies have shown that the dental crown dimensions of permanent dentition tend to be larger in men than in women; the lower lateral incisors and canines are the most useful teeth for determining dental sexual dimorphism (12). However, a study in Nepal (8) provided a contradictory conclusion, in that the mesiodistal measurements of the lower second premolars were larger in women than in men; this study indicated that the measurement variables had greater utility in sex assessment when using discriminant analyses. Thereafter, several studies attempted to identify the differences between sexes through measurements of human dental crowns in different populations, with inconsistent results. (1, 4, 13)

Considering the number of anatomical studies in the dental literature and the diversity of their outcomes, this observed variation in dental dimensions is of fundamental importance; the future of dental anatomy depends on the use of new methods to study anatomical variations. (14) The present study aimed to determine whether the pattern of dental sexual dimorphism found in a small number of samples by previous researchers is consistent when tested more extensively across a wider range of populations.

METHODS:

Protocol

The present study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA statement for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The review protocol can be accessed online (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO. Registration number: CRD42015023373).

Search Strategy

A systematic review was performed. The electronic literature search was performed by two independent examiners to guarantee the quality of the data collected in the studies. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, Lilacs, Science direct, Medline, BBO and Cochrane Reviews. The search was performed during the period between October 2015 and July 2016. In addition to the peer-reviewed literature search, a grey literature and hand search was performed in USP web science (http://www.sibi.usp.br/bibliotecas/) and Banco de Theses CAPES. No language restrictions or dates were imposed; keyword searches used Boolean operators. The search terms included: Sex characteristics, Odontometric, Dental index, Dental index determination, Sex determination, Dental dimorphism, Sexual dimorphism, and Tooth crown; these terms were present in the title or abstract of identified studies.

Inclusion criteria

Original studies that were conducted in different population groups and investigated mesiodistal crowns in the permanent teeth were the targets of this analysis. Comparison groups were male and female populations. Outcomes included studies that measured all right-sided teeth, except the third molars. Analyses of mesiodistal crowns, odontometric population characteristics, and sexual dimorphism from cross-sectional studies were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies using non-human teeth, skeletal remains, or a very specific study population were excluded. Studies that did not report the sample population and studies without full text accessibility were not reviewed.

Data items

Data were collected regarding the mesiodistal measurements of each tooth crown: population, sample, calibration, standard deviation, collection instrument, and detection of sexual dimorphism. In the event of any irregularities in the data, authors were contacted by email for supplementary information. If these were unavailable, the article was excluded.

Synthesis of results

Syntheses of the results are presented according to sex, specifically on the right side. Analyses did not include the right and left sides together.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using BioStat v. 5.3 (InstitutoMamirauá, Amazonas, Brazil) and STATA 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software for mean differences between sexes with respect to teeth. Dissimilarity indices between studies were determined by heterogeneity tests using both the chi-squared test and I-squared statistic. Percentage dimorphism was calculated as (median male/median female -1) × 100. (15) A positive value indicated that the male tooth dimension was larger, whereas a negative value indicated that the female tooth dimension was larger. The total percentage dimorphism was the sum of all percentages / number of all teeth. (16)

RESULTS

Study selection:

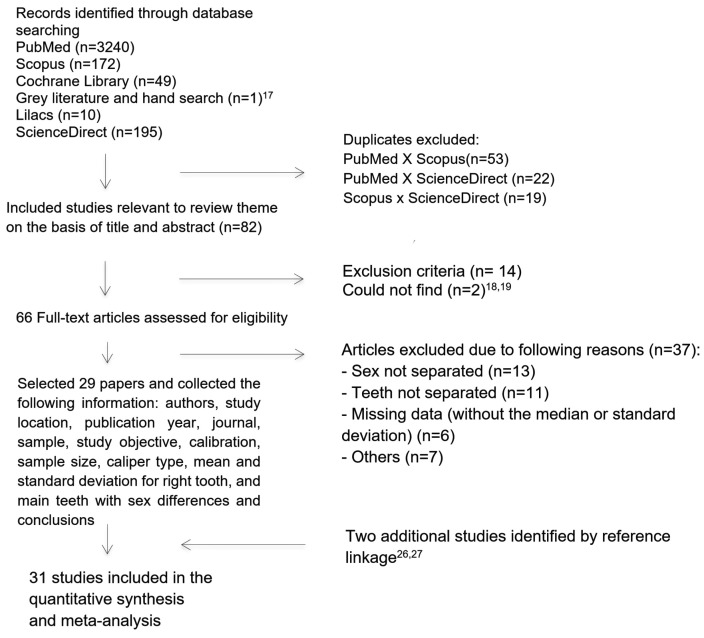

Potential records identified through database searches were as follows: PubMed (n=3240), Scopus (n=172), Cochrane Library (n=49), Hand Searching (n=1), Lilacs (n=10), and ScienceDirect (n=195). Principal duplicates excluded were as follows: PubMed X Scopus (n=53), PubMed X ScienceDirect (n=22), and Scopus X ScienceDirect (n=19). According to pre-determined inclusion criteria, 82 abstracts were initially obtained. An article was read in full if one reviewer considered the abstract to be of potential relevance. If there was a lack of consensus regarding study credibility between the two reviewers, a third examiner performed the evaluation. In grey literature just one thesis (17) was found.

Full text articles that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded from further analysis (n=14). Two additional studies were excluded because the full article could not be obtained, (18, 19) despite direct contact with the authors. Sixty-six full text articles were assessed for eligibility. Thirty-seven studies in this section were excluded for a variety of reasons: sex not separated (n=13); teeth not separated (n=11); missing data (without the median or standard deviation) (n=6); identical values in the tables for upper and lower teeth; (20) male data only; (21, 22) duplicate data from the same population; (23) graphics only, (24) data were not for mesiodistal crowns; (25) only the values of the differences were available. (26) Therefore, two additional studies were identified by reference linkage. (27, 28) Finally, 31 studies were selected for review and meta-analysis. The details and results of the search strategy are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the study selection process

Risk of bias results

The risk of individual bias is shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, which compare the selected studies and their relative contribution to the final results of the systematic review.

Table 4. Risk of bias: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented in all 31 included studies.

| Articles | Khamis et al.28, Angadi et al.30, Ling & Wong34, Yuen & Tang.40 | Thapar et al.4, Martins-Filho 17, Al-Gunaid et al. 31, Phabhu & Acharya.32, Hashim & Al-Ghamdi.38, Hattab et al.41 | Kieser et al.45, Richardson &Malhotra.49, Moorrees et al.51 | Lukacs &Hemphill.43, Bishara et al.44, Axelsson &Kirveskari.46 | Archarya & Mainali.8 , Ngom et al.35, Ates et al.36 | Fernandes et al.1 | Antoszewski et al.33 | Santoro et al.39 | Hashim & Murshid38 | Singh &Goyal37 | Mitsea et al. 29 | Castillo et al. 27 | Lund & Mörnstad6 | Ghose & Baghdady48, Garn et al.13,50, Potter et al.47 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibrating | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NO | Not clear | Not clear | No | Yes | Yes | No | Not clear |

| Sample size >110 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | Yes | NO | NO | Yes |

| Random sample | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Not clear | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Digital caliper | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Standard deviation <0.7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Differences detected | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all 31 included studies.

Some studies had an insufficient sample size (n<110) for in-depth analysis regarding dental sexual dimorphism, especially if the purpose of the study was to analyze differences between the sexes. (1, 6, 27, 33, 35-39) Therefore, we considered that these studies presented a high risk of bias for the analysis of differences in the dimensions of dental crowns. However, these smaller sample studies would have had less influence on our meta-analysis.

Only two studies (29, 37) presented a standard deviation above 0.7; although this value did not apply to all teeth, this may indicate methodological flaws, and was considered a risk of bias. In the specific case of a North Indian study, (37) no examiner calibration was reported. In another study, (29) the sample was considered insufficient to detect a high standard deviation.

Potential problems regarding tooth measurement method were evaluated; however, a significant difference between manual and digital methods was not found, indicating that these are interchangeable (52). Despite this indication, we considered manual measurements (37, 39, 43-46, 48-50) as a risk of bias in the present review, due to their reduced accuracy with respect to digital calipers. However, it should be noted that some studies were published before the advent of digital calipers. (44-46, 49, 5) In addition, non-specification of the calipers used (13, 27) was considered a risk of bias in the present study,

In one study, (33) the odontometric characteristics of transsexual women were evaluated in comparison with male and female subjects; this review collected male and female participants. One study that did not find sexual dimorphism (27) was considered a type of bias, because our initial hypothesis was that there is difference in mesiodistal measurements in all teeth. In some studies (37-39), the differences between single teeth were unclear; therefore, no statistical proof could be considered.

Three studies (6, 33, 37) did not describe the calibration process and were therefore considered to have a risk of bias. In other studies, (13, 38, 39, 47, 48, 50) the risk of bias was unclear due to poorly defined calibration methodologies or a lack of information.

Regarding the type of sample, we considered whether the sample was representative of the population, on the basis of being randomized or specifically selected.

Most selected studies (6, 8, 13, 17, 19, 31, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 45, 47-50) used a sample of convenience and were therefore considered to have a high risk of bias. However, we must consider that in some of studies, the aim was not to determine dental sexual differences. The risk of bias in one study (1) was unclear, because, despite the authors' concern for dividing the sample by racial origin, the sample size per group was small.

The use of the right side only as a reference does not influence the results, because the differences due to asymmetry in humans are not significant. (15, 17, 27, 31, 38, 40, 53)

We did not separate the studies based on whether they measured plaster casts or human teeth. It has been shown that human teeth and plaster measurements can produce similar results; (53) therefore, this was not considered a risk of bias.

We also excluded skeletal remains in this review, because the mesiodistal diameter of the crown is typically not preserved; (54) similarly, very specific populations exhibit particular intrinsic (genetic) and extrinsic (environmental) variables. (13, 16) Therefore, our results focused on young adults with permanent teeth.

Meta-analysis by individual tooth

The meta-analysis graphs were generated by teeth. The mean differences between male and female subjects are in Table 5. The I-squared statistic should be interpreted as follows: 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 50% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity. (55) The results of Egger's test for small-study effects were not significant and did not indicate publication bias.

Table 5. Meta-analysis by individual tooth: mean differences between male and female subjects.

| Tooth | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17# | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 0.242 (0.013) |

0.174 (0.014) |

0.359 (0.011) |

0.170 (0.011) |

0.145 (0.011) |

0.274 (0.013) |

0.306 (0.020) |

0.091 (0.008) |

0.135 (0.009) |

0.378 (0.010) |

0.165 (0.010) |

0.171 (0.012) |

0.348 (0.015) |

0.365 (0.020) |

| 95% CI | 0.2167 0.26 75 0.1478 a 0.2030 0.3369 a 0.3815 0.1490 a 0.1922 0.1227 a 0.1667 0.2476 a 0.3009 0.2648 a 0.3441 | 0.1469 0.2018 | 0.3368 0.3814 | 0.1492 0.1924 | 0.1238 0.1676 | 0.2480 0.3011 | 0.2667 0.3452 | 0.0743 0.1083 | 0.1169 0.1539 | 0.3585 0.3974 | 0.1445 0.1869 | 0.1481 0.1951 | 0.3188 0.3778 | 0.3259 0.4041 |

| P= | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

|

Heterogeneity test I-squared |

34.4% | 34.4 % | 23.7% | 10.2% | 36.4% | 44.5% | 78.1% | 44.2% | 24.3% | 44.0% | 57.7% | 36.6% | 42.9% | 47.3% |

| P=0.017 | P=0.017 | P=0.087 | P=0.284 | P=0.011 | P=0.001 | P=0.000 | P=0.001 | P=0.082 | P=0.001 | P=0.000 | P=0.011 | P=0.001 | P=0.007 | |

|

Publication bias (Egger's test) |

P= 0.424 | P= 0.378 | P= 0.549 | P= 0.490 | P= 0.886 | P= 0.391 | P= 0.811 | P= 0.220 | P= 0.603 | P= 0.437 | P= 0.423 | P= 0.726 | P= 0.279 | P= 0.772 |

DISCUSSION

The primary question addressed by this review constituted whether the tooth crown sexual dimorphism pattern previously reported in limited samples could be verified when tested more extensively across a range of populations. Over 6700 males and females participated in the 31 included trials.

Tables 1 and 2 present the 31 selected articles, publication dates, study population, sample population and main objectives. Of these published studies, only one (11) failed to find sexual dimorphism through mesiodistal measurements, while another (30) found it only in canines. However, due to the risk of bias, only 4 articles (Table 3) fulfilled the requirements for all considered items, which makes this study very vulnerable to bias.

Table 1. The 31 selected articles including publication dates, sample, study population, and main objectives.

| Article | Male sample | Female sample | Population sample | Year | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martins-Filho17 | 100 | 100 | Brazilians | 2013 | Sexual dimorphism through dental measurements. |

| Khamis et al.28 | 200 | 200 | Malaysians Chinese, Tamils and Malays | 2014 | Sex prediction model to Malaysians. |

| Mitsea et al.29 | 64 | 108 | Greeks | 2014 | Sex assessment from tooth measurements |

| Angadi et al.30 | 294 | 306 | Indians | 2013 | Develop a logistic regression for sex prediction. |

| Fernandes et al.1 | 50 | 50 | Brazilians African ancestry, Caucasian ancestry and Japanese ancestry | 2013 | Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal crown with normal occlusion and compared between these populations. |

| Thapar et al.4 | 96 | 104 | Indians | 2012 | Correlation between tooth and skull size in sex determination. |

| Al-Gunaid et al.31 | 82 | 94 | Yemeni Arabians | 2012 | Determination of mean mesiodistal crown and Bolton's ratios. |

| Castillo et al.27 | 39 | 27 | Colombians | 2011 | Determination of the mean diameter of each tooth, sexual dimorphism, and bilateral symmetry. |

| Phabhu & Acharya.32 | 52 | 52 | Indians | 2009 | Determination of odontometric standards and sexual dimorphism with statistical analyses. |

| Antoszewski et al.33 | 67 | 62 | Polonies | 2009 | Odontometric characteristics of transsexual women in comparison of males and females. |

| Archarya & Mainali8 | 60 | 56 | Nepalese | 2007 | Sexual dimorphism through dental measurements. |

| Ling & Wong (34) | 264 | 148 | Southern Chinese | 2007 | Sexual dimorphism through dental measurements. |

| Ngom et al.35 | 52 | 52 | Moroccan and Senegalese | 2007 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns. |

| Ates et al.36 | 50 | 50 | Turks | 2006 | Sexual dimorphism through dental measurements and compared with others populations. |

| Singh & Goyal37 | 40 | 70 | North Indians - Punjabis | 2006 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns. |

| Hashim & Al-Ghamdi38 | 60 | 60 | Saudi Arabians | 2005 | Comparison of mesiodistal crown between normal occlusion and malocclusion in both sexes. |

| Santoro et al.39 | 36 | 18 | Dominican Americans | 2000 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns. |

| Lund & Mörnstad6 | 28 | 28 | Swedes | 1999 | Investigation of the accuracy with which sex can be differentiated by odontometric analyses. |

| Yuen & Tang40 | 60 | 49 | Southern Chinese | 1997 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns and compared with others populations. |

| Hattab et al.41 | 82 | 110 | Jordanians | 1996 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns |

| Hashim & Murshid (42) | 60 | 60 | Saudi Arabians | 1993 | Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal crowns. |

| Lukacs & Hemphill43 | 344 | 237 | Northwest India – Bhils, Rajput and Garasias | 1993 | Analysis of odontometric characteristics compared among these populations. |

| Bishara et al.44 | 91 | 80 | Americans, Mexican and Egyptians | 1989 | Odontometric characteristics of normal occlusion and comparison among these populations. |

| Kieser et al.45 | 55 | 65 | South Africa Caucasoid | 1985 | Odontometric characteristics of this population and comparison with other populations. |

| Axelsson & Kirveskari46 | 465* | 482* | Icelanders | 1983 | Odontometric characteristics and Sexual dimorphism. |

| Potter et al.47 | 183 | 164 | Filipinos | 1981 | Odontometric characteristics of this population and sexual dimorphism compared with other populations. |

| Ghose & Baghdady48 | 30 | 30 | Iraqis, Bedouins and Yemenites | 1979 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns. |

| Richardson & Malhotra49 | 158 | 160 | Americans Negroes | 1975 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns. |

| Garn et al.50 | 288 | 322 | Americans - Southwest | 1968 | Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal crowns. |

| Garn et al.13 | 204 | 258 | Americans - Ohio | 1967 | Odontometric characteristics of this population and comparison with other populations. |

| Moorrees et al.51 | 85 | 87 | Americans - Northeast | 1957 | Analysis of mesiodistal crowns: permanent and deciduous. |

* Lower incisors

Table 2. All mesiodistal values of crowns for every tooth (mean and standard deviation) found in the 31 selected studies separated by male and female.

| TOOTH | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populations | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F |

|

Brazilians (2013) |

8.75 0.70 |

6.94 0.64 |

8.13 0.56 |

7.15 0.44 |

7.03 0.55 |

10.95 0.70 |

10.04 0.87 |

5.36 0.82 |

5.75 0.54 |

7.17 0.64 |

7.36 0.55 |

7.56 0.52 |

10.80 1.08 |

10.89 0.78 |

| 8.52 0.69 |

6.70 0.62 |

7.80 0.54 |

6.91 0.55 |

6.75 0.58 |

10.45 0.82 |

9.75 0.85 |

5.18 0.52 |

5.62 0.63 |

6.83 0.50 |

7.10 0.56 |

7.28 0.57 |

10.63 0.62 |

10.49 0.72 |

|

|

Malaysian Chinese (2014) |

8.89 0.45 |

7.35 0.52 |

8.33 0.47 |

7.73 0.40 |

7.32 0.44 |

10.68 0.49 |

10.32 0.45 |

5.60 0.31 |

6.14 0.35 |

7.23 0.40 |

7.54 0.35 |

7.54 0.45 |

11.67 0.47 |

10.81 0.49 |

| 8.55 0.47 |

7.05 0.56 |

8.03 0.46 |

7.48 0.46 |

7.06 0.39 |

10.36 0.50 |

9.88 0.49 |

5.46 0.35 |

6.05 0.35 |

6.86 0.39 |

7.32 0.38 |

7.25 0.44 |

11.20 0.53 |

10.14 0.40 |

|

|

Malaysian Tamils (2014) |

8.81 0.32 |

6.99 0.41 |

7.92 0.34 |

7.31 0.36 |

6.97 0.37 |

10.64 0.51 |

10.38 0.55 |

5.52 0.30 |

6.07 0.36 |

6.99 0.36 |

7.33 0.32 |

7.40 0.35 |

11.40 0.58 |

10.57 0.28 |

| 8.52 0.46 |

6.89 0.51 |

7.68 0.37 |

7.17 0.37 |

6.81 0.31 |

10.37 0.50 |

10.01 0.55 |

5.41 0.31 |

5.89 0.34 |

6.62 0.29 |

7.19 0.38 |

7.23 0.45 |

11.07 0.52 |

10.29 0.51 |

|

|

Malays (2014) |

8.66 0.46 |

7.07 0.54 |

8.25 0.38 |

7.47 0.45 |

7.03 0.40 |

10.62 0.48 |

10.13 0.48 |

5.54 0.34 |

6.13 0.34 |

7.19 0.41 |

7.39 0.49 |

7.34 0.47 |

11.60 0.53 |

10.55 0.64 |

| 8.44 0.51 |

6.91 0.62 |

7.81 0.46 |

7.40 0.38 |

6.96 0.41 |

10.47 0.46 |

9.90 0.51 |

5.43 0.30 |

6.06 0.36 |

6.77 0.34 |

7.27 0.42 |

7.32 0.40 |

11.32 0.46 |

10.27 0.57 |

|

|

Greeks (2014) |

8.93 0.82 |

6.49 1.67 |

8.04 0.51 |

6.16 2.31 |

6.86 0.45 |

10.06 2.00 |

- - |

5.66 0.66 |

6.11 0.56 |

7.17 0.52 |

6.27 2.36 |

5.87 2.86 |

10.43 2.33 |

- - |

| 8.59 0.95 |

6.45 1.36 |

7.74 0.51 |

6.16 2.07 |

6.74 0.56 |

9.38 2.65 |

x x |

5.45 0.49 |

5.95 0.71 |

6.83 0.48 |

6.55 1.66 |

6.24 2.40 |

9.84 2.91 |

x x |

|

|

Indians (2013) |

8.58 0.57 |

6.81 0.64 |

7.84 0.51 |

7.05 0.50 |

6.68 0.47 |

10.29 0.55 |

9.83 0.73 |

5.41 0.37 |

5.94 0.41 |

6.84 0.45 |

7.03 0.50 |

7.09 0.54 |

10.96 0.65 |

10.26 0.66 |

| 8.38 0.59 |

6.64 0.64 |

7.51 0.48 |

6.89 0.48 |

6.58 0.57 |

10.09 0.57 |

9.49 0.75 |

5.35 0.43 |

5.82 0.39 |

6.47 0.40 |

6.96 0.46 |

6.97 0.50 |

10.70 0.61 |

9.92 0.62 |

|

|

Brazilian African ancestry (2013) |

9.05 0.56 |

7.37 0.53 |

8.26 0.50 |

7.63 0.59 |

7.10 0.67 |

10.96 0.62 |

- - |

5.61 0.40 |

6.33 0.45 |

7.44 0.57 |

7.70 0.46 |

7.63 0.57 |

11.66 0.49 |

- - |

| 8.63 0.57 |

7.03 0.68 |

7.73 0.54 |

7.31 0.64 |

6.84 0.52 |

10.22 0.48 |

x x |

5.25 0.40 |

5.97 0.42 |

6.86 0.49 |

7.30 0.54 |

7.11 0.60 |

11.09 0.58 |

x x |

|

|

Brazilian Caucasian ancestry (2013) |

8.70 0.55 |

6.53 0.48 |

7.82 0.45 |

6.86 0.49 |

6.60 0.34 |

10.01 0.39 |

- - |

5.29 0.29 |

5.81 0.31 |

6.84 0.33 |

7.05 0.43 |

7.04 0.38 |

11.01 0.77 |

- - |

| 8.40 0.36 |

6.51 0.50 |

7.54 0.46 |

6.89 0.42 |

6.56 0.31 |

9.80 0.55 |

x x |

5.14 0.21 |

5.71 0.30 |

6.48 0.33 |

6.85 0.43 |

6.90 0.42 |

10.42 0.57 |

x x |

|

|

Brazilian Japanese ancestry (2013) |

8.54 0.40 |

7.16 0.36 |

7.95 0.44 |

7.35 0.52 |

6.82 0.40 |

10.36 0.57 |

- - |

5.31 0.35 |

5.92 0.36 |

7.02 0.42 |

7.24 0.43 |

6.98 0.48 |

11.21 0.41 |

- - |

| 8.36 0.39 |

6.74 0.56 |

7.70 0.50 |

7.16 0.39 |

6.69 0.37 |

10.19 0.41 |

x x |

5.07 0.22 |

5.62 0.32 |

6.61 0.48 |

7.11 0.47 |

7.01 0.33 |

11.05 0.51 |

x x |

|

|

Indians (2012) |

8.50 0.61 |

6.70 0.62 |

7.80 0.51 |

6.90 0.52 |

6.50 0.48 |

10.10 0.60 |

9.90 0.77 |

5.30 0.36 |

5.90 0.43 |

6.80 0.44 |

6.90 0.42 |

6.90 0.60 |

10.80 0.63 |

10.31 0.64 |

| 8.40 0.73 |

6.60 0.68 |

7.50 0.97 |

6.70 0.58 |

6.40 0.63 |

9.97 0.74 |

9.60 0.80 |

5.40 0.39 |

5.80 0.44 |

6.50 0.36 |

7.00 0.49 |

6.80 0.53 |

10.60 0.66 |

9.90 0.70 |

|

|

Yemeni Arabians (2012) |

8.57 0.56 |

6.50 0.52 |

7.57 0.41 |

6.68 0.50 |

6.33 0.53 |

9.95 0.65 |

- - |

5.21 0.44 |

5.74 0.44 |

6.73 0.43 |

6.74 0.51 |

6.80 0.55 |

10.87 0.74 |

- - |

| 8.34 0.61 |

6.40 0.66 |

7.30 0.44 |

6.49 0.49 |

6.22 0.53 |

9.82 0.55 |

x x |

5.12 0.48 |

5.62 0.48 |

6.42 0.38 |

6.61 0.50 |

6.67 0.49 |

10.54 0.62 |

x x |

|

|

Colombians 2011) |

8.65 0.62 |

6.89 0.57 |

7.91 0.58 |

7.26 0.78 |

7.00 0.72 |

10.16 1.26 |

- - |

5.32 0.46 |

5.86 0.50 |

6.91 0.51 |

7.25 0.44 |

7.21 0.50 |

11.33 0.57 |

- - |

| 8.37 0.46 |

6.88 0.58 |

7.93 0.72 |

7.19 0.77 |

6.90 0.61 |

10.19 0.55 |

x x |

5.30 0.38 |

5.94 0.46 |

6.83 0.62 |

7.22 0.44 |

7.11 0.63 |

11.03 0.64 |

x x |

|

|

Indians (2009) |

8.39 0.61 |

6.63 0.78 |

7.65 0.54 |

6.87 0.64 |

6.50 0.63 |

9.96 0.55 |

9.43 0.72 |

5.37 0.40 |

5.88 0.35 |

6.61 0.38 |

6.76 0.45 |

6.88 0.66 |

10.80 0.67 |

9.89 0.69 |

| 8.29 0.57 |

6.50 0.59 |

7.44 0.40 |

6.77 0.45 |

6.59 0.83 |

9.79 0.49 |

9.24 0.75 |

5.23 0.37 |

5.75 0.33 |

6.45 0.41 |

6.78 0.46 |

6.74 0.48 |

10.54 0.56 |

9.83 0.64 |

|

|

Polonies (2009) |

8.68 0.61 |

6.61 0.68 |

7.78 0.72 |

6.73 0.52 |

6.49 0.50 |

10.52 0.92 |

9.70 0.85 |

5.44 0.39 |

5.93 0.43 |

6.76 0.54 |

6.92 0.53 |

6.97 0.52 |

11.20 0.83 |

10.46 0.79 |

| 8.54 0.67 |

6.47 0.63 |

7.48 0.81 |

6.80 0.59 |

6.53 0.60 |

10.16 0.82 |

9.54 0.91 |

5.30 0.43 |

5.87 0.35 |

6.49 0.54 |

6.90 0.53 |

6.76 0.61 |

10.69 0.82 |

10.20 0.83 |

|

|

Nepalese (2007) |

8.79 0.62 |

6.87 0.67 |

7.94 0.45 |

7.00 0.42 |

6.61 0.37 |

10.61 0.56 |

9.76 0.66 |

5.45 0.38 |

6.05 0.40 |

6.96 0.39 |

7.08 0.40 |

6.96 0.42 |

11.10 0.58 |

10.50 0.67 |

| 8.52 0.55 |

6.81 0.57 |

7.60 0.40 |

6.96 0.45 |

6.53 0.39 |

10.35 0.56 |

9.69 0.69 |

5.40 0.33 |

5.93 0.33 |

6.58 0.35 |

7.02 0.39 |

7.02 0.76 |

10.95 0.61 |

10.13 0.63 |

|

|

Southern Chinese (2006) |

8.85 0.53 |

7.36 0.59 |

8.30 0.47 |

7.77 0.42 |

7.26 0.36 |

10.99 0.51 |

10.26 0.49 |

5.62 0.34 |

6.22 0.41 |

7.31 0.42 |

7.58 0.42 |

7.56 0.41 |

11.69 0.60 |

10.73 0.67 |

| 8.69 0.47 |

7.18 0.61 |

7.92 0.37 |

7.57 0.35 |

7.10 0.34 |

10.67 0.50 |

9.95 0.65 |

5.57 0.33 |

6.14 0.31 |

6.89 0.34 |

7.36 0.34 |

7.35 0.37 |

11.29 0.51 |

10.37 0.55 |

|

|

Moroccan (2007) |

9.08 0.60 |

7.71 0.58 |

8.11 0.53 |

7.29 0.47 |

6.90 0.45 |

10.69 0.54 |

- - |

5.74 0.35 |

6.24 0.44 |

7.06 0.55 |

7.46 0.57 |

7.44 0.75 |

11.20 0.66 |

- - |

| 8.80 0.65 |

6.83 0.67 |

7.69 0.43 |

7.12 0.41 |

6.72 0.36 |

10.56 0.66 |

x x |

5.48 0.42 |

5.96 0.46 |

6.70 0.37 |

7.14 0.45 |

7.09 0.42 |

11.02 0.58 |

x x |

|

|

Senegalese (2007) |

9.22 0.67 |

7.42 0.75 |

8.36 0.53 |

7.81 0.46 |

7.27 0.48 |

10.91 0.68 |

- - |

5.58 0.43 |

6.23 0.48 |

7.54 0.55 |

8.01 0.64 |

7.89 0.64 |

11.1 0,65 |

- - |

| 8.98 0.49 |

7.37 0.68 |

7.99 0.52 |

7.73 0.42 |

7.03 0.42 |

10.70 0.51 |

x x |

5.56 0.37 |

6.13 0.39 |

7.10 0.40 |

7.72 0.48 |

7.68 0.44 |

11.20 0.47 |

x x |

|

|

Turks (2006) |

8.51 0.49 |

6.75 0.55 |

7.89 0.45 |

6.97 0.49 |

6.67 0.60 |

10.24 0.51 |

10.03 0.72 |

5.37 0.36 |

5.88 0.43 |

6.95 0.48 |

7.02 0.51 |

7.13 0.47 |

10.98 0.61 |

10.46 0.76 |

| 8.41 0.52 |

6.50 0.59 |

7.49 0.38 |

6.86 0.39 |

6.54 0.44 |

10.04 0.61 |

9.88 0.56 |

5.32 0.34 |

5.86 0.34 |

6.58 0.34 |

6.95 0.39 |

7.01 0.42 |

10.80 0.62 |

10.39 0.63 |

|

|

North Indians (2006) |

9.05 3.00 |

7.07 2.66 |

8.16 2.85 |

7.35 2.71 |

7.10 2.66 |

10.35 3.21 |

9.95 3.15 |

5.68 2.38 |

6.31 2.50 |

7.26 2.69 |

7.42 2.72 |

7.55 2.73 |

11.23 3.35 |

10.33 3.22 |

| 8.62 2.93 |

6.95 2.63 |

7.86 2.80 |

7.20 2.68 |

6.76 2.60 |

10.03 3.16 |

9.57 3.08 |

5.55 2.35 |

5.98 2.44 |

6.88 2.61 |

7.02 2.62 |

7.17 2.67 |

10.80 3.28 |

10.01 3.16 |

|

|

Saudi Arabia (2005) |

8.78 0.60 |

6.80 0.58 |

7.95 0.48 |

6.98 0.41 |

6.48 0.42 |

10.14 0.57 |

- - |

5.46 0.37 |

5.95 0.44 |

6.88 0.47 |

7.03 0.44 |

6.86 0.50 |

11.08 0.66 |

- - |

| 8.60 0.52 |

6.68 0.51 |

7.54 0.42 |

6.87 0.39 |

6.40 0.45 |

10.08 0.63 |

x x |

5.34 0.36 |

5.81 0.39 |

6.53 0.44 |

6.91 0.42 |

6.96 0.65 |

10.71 0.58 |

x x |

|

|

Dominican Americans (2000) |

8.96 0.67 |

6.98 0.69 |

8.15 0.52 |

7.54 0.49 |

7.10 0.42 |

10.81 0.70 |

- - |

5.56 0.36 |

6.16 0.42 |

7.12 0.55 |

7.48 0.52 |

7.53 0.56 |

11.32 0.60 |

- - |

| 8.72 0.56 |

6.99 0.56 |

7.84 0.48 |

7.37 0.44 |

6.97 0.49 |

10.51 0.66 |

x x |

5.47 0.35 |

6.08 0.36 |

6.82 0.40 |

7.44 0.51 |

7.34 0.49 |

11.02 0.67 |

x x |

|

|

Suécia (1999) |

8.88 0.68 |

6.98 0.50 |

8.26 0.49 |

6.87 0.31 |

6.73 0.52 |

11.00 0.63 |

10.40 0.65 |

5.48 0.43 |

6.09 0.39 |

7.19 0.52 |

7.12 0.38 |

7.36 0.53 |

11.13 0.63 |

10.52 0.76 |

| 8.48 0.60 |

6.65 0.55 |

7.61 0.48 |

6.76 0.39 |

6.65 0.53 |

10.58 0.72 |

9.94 0.61 |

5.32 0.48 |

5.90 0.41 |

6.56 0.39 |

6.98 0.47 |

6.92 0.38 |

10.80 0.60 |

10.22 0.57 |

|

|

Hong Kong (1997) |

8.73 0.51 |

7.18 0.60 |

8.30 0.41 |

7.76 0.42 |

7.24 0.42 |

10.41 0.50 |

- - |

5.48 0.33 |

6.10 0.33 |

7.29 0.37 |

7.58 0.36 |

7.44 0.38 |

11.30 0.54 |

- - |

| 8.66 0.46 |

7.12 0.50 |

8.02 0.40 |

7.54 0.43 |

7.07 0.47 |

10.11 0.45 |

x x |

5.53 0.32 |

6.13 0.35 |

6.92 0.43 |

7.44 0.47 |

7.28 0.40 |

11.15 0.44 |

x x |

|

|

Jordanians (1996) |

8.99 0.61 |

6.99 0.66 |

8.10 0.59 |

7.19 0.49 |

6.99 0.43 |

10.57 0.53 |

- - |

5.67 0.33 |

6.23 0.43 |

6.94 0.44 |

7.39 0.45 |

7.40 0.41 |

11.29 0.62 |

- - |

| 8.66 0.52 |

6.72 0.60 |

7.68 0.50 |

7.02 0.47 |

6.84 0.54 |

10.25 0.57 |

x x |

5.54 0.39 |

6.09 0.52 |

6.61 0.45 |

7.03 0.39 |

7.16 0.48 |

10.84 0.66 |

x x |

|

|

Saudi Arabians (1993) |

8.60 0.67 |

6.77 0.58 |

7.80 0.50 |

7.00 0.56 |

6.59 0.43 |

10.59 0.59 |

- - |

5.33 0.36 |

5.99 0.59 |

6.80 0.40 |

6.88 0.65 |

7.10 0.49 |

11.05 0.69 |

- - |

| 8.63 0.46 |

6.58 0.41 |

7.37 0.46 |

6.84 0.31 |

6.58 0.32 |

10.48 0.42 |

x x |

5.37 0.29 |

6.00 0.40 |

6.50 0.43 |

7.03 0.39 |

7.07 0.31 |

10.89 0.54 |

x x |

|

|

Northwest India – Bhils (1993) |

8.57 0.52 |

6.76 0.55 |

7.79 0.44 |

7.02 0.44 |

6.52 0.46 |

10.37 0.54 |

9.58 0.67 |

5.37 0.36 |

5.96 0.42 |

6.89 0.38 |

7.00 0.47 |

7.07 0.48 |

11.22 0.62 |

10.36 0.52 |

| 8.21 0.62 |

6.43 0.60 |

7.40 0.42 |

6.90 0.43 |

6.41 0.43 |

10.01 0.48 |

9.19 0.70 |

5.28 0.35 |

5.81 0.38 |

6.43 0.38 |

6.87 0.42 |

6.93 0.47 |

10.89 0.65 |

10.11 0.65 |

|

|

Northwest India – Rajputs (1993) |

8.62 0.56 |

6.70 0.52 |

7.64 0.48 |

6.77 0.47 |

6.45 0.46 |

10.35 0.57 |

9.71 0.84 |

5.30 0.40 |

5.87 0.44 |

6.86 0.46 |

6.80 0.44 |

6.88 0.50 |

11.02 0.60 |

9.89 0.76 |

| 8.28 0.67 |

6.47 0.51 |

7.32 0.41 |

6.64 0.53 |

6.30 0.62 |

10.00 0.57 |

9.10 0.70 |

5.18 0.38 |

5.68 0.33 |

6.42 0.35 |

6.65 0.50 |

6.62 0.55 |

10.54 0.67 |

9.51 0.63 |

|

|

Northwest India – Garasias (1993) |

8.53 0.61 |

6.73 0.65 |

7.67 0.48 |

6.97 0.58 |

6.49 0.71 |

10.53 0.59 |

9.47 0.84 |

5.30 0.43 |

5.94 0.44 |

6.84 0.48 |

6.91 0.50 |

6.94 0.53 |

10.89 0.56 |

10.22 0.67 |

| 8.33 0.54 |

6.47 0.67 |

7.28 0.44 |

6.71 0.45 |

6.29 0.57 |

10.23 0.58 |

9.20 0.84 |

5.19 0.39 |

5.76 0.41 |

6.38 0.39 |

6.77 0.44 |

6.81 0.50 |

10.56 0.52 |

9.74 0.71 |

|

|

Americans (1989) |

8.60 0.50 |

6.70 0.40 |

7.80 0.50 |

6.90 0.40 |

6.70 0.4 |

10.5 0.6 |

- - |

5.4 0.40 |

5.90 0.40 |

6.80 0.40 |

6.9 0.40 |

7.0 0.4 |

11.00 0.70 |

- - |

| 8.50 0.70 |

6.60 0.60 |

7.50 0.40 |

6.70 0.40 |

6.50 0.40 |

10.10 0.50 |

x x |

5.20 0.40 |

5.75 0.40 |

6.40 0.40 |

6.80 0.40 |

6.80 0.30 |

10.40 0.60 |

x x |

|

|

Mexican (1989) |

8.40 0.60 |

6.60 0.60 |

7.90 0.60 |

6.90 0.305 |

7.00 0.50 |

10.55 0.50 |

- - |

5.50 0.40 |

6.00 0.40 |

6.90 0.30 |

7.00 0.40 |

7.30 0.40 |

10.90 0.60 |

- - |

| 8.20 0.50 |

6.50 0.60 |

7.60 0.50 |

6.60 0.40 |

6.60 0.40 |

10.20 0.70 |

x x |

5.40 0.40 |

5.80 0.40 |

6.45 0.40 |

6.70 0.50 |

7.00 0.60 |

10.50 0.50 |

x x |

|

|

Egyptians (1989) |

8.90 0.50 |

6.90 0.50 |

7.90 0.50 |

7.10 0.40 |

6.80 0.30 |

10.40 0.50 |

- - |

5.40 0.30 |

5.90 0.40 |

6.90 0.40 |

7.10 0.40 |

7.20 0.40 |

11.0 0.75 |

- - |

| 8.90 0.50 |

6.80 0.60 |

7.50 0.40 |

7.10 0.40 |

6.70 0.30 |

10.25 0.50 |

x x |

5.55 0.50 |

6.00 0.30 |

6.60 0.40 |

7.10 0.35 |

7.20 0.40 |

11.00 0.60 |

x x |

|

|

South Africa Caucasoid (1985) |

8.94 0.70 |

7.08 0.54 |

8.43 0.59 |

7.53 0.51 |

7.49 0.63 |

11.22 0.65 |

10.71 0.67 |

5.54 0.32 |

6.20 0.43 |

7.34 0.48 |

7.68 0.50 |

7.81 0.51 |

11.56 0.58 |

10.80 0.62 |

| 8.40 0.66 |

6.56 0.57 |

7.74 0.42 |

7.24 0.45 |

7.04 0.41 |

10.74 0.50 |

10.00 0.49 |

5.33 0.37 |

6.01 0.46 |

6.79 0.36 |

7.30 0.53 |

7.38 0.44 |

10.88 0.55 |

10.20 0.59 |

|

|

Icelanders (1983) |

8.99 0.54 |

6.95 0.54 |

8.14 0.42 |

7.22 0.41 |

6.89 0.43 |

10.98 0.57 |

10.08 0.58 |

5.59 0.35 |

6.20 0.36 |

7.13 0.41 |

7.30 0.41 |

7.45 0.46 |

11.45 0.58 |

10.85 0.60 |

| 8.75 0.52 |

6.83 0.51 |

7.79 0.40 |

7.07 0.42 |

6.84 0.42 |

10.70 0.57 |

9.78 0.53 |

5.48 0.34 |

6.02 0.37 |

6.80 0.35 |

7.12 0.42 |

7.27 0.44 |

11.12 0.60 |

10.49 0.64 |

|

|

Filipinos (1991) |

8.33 0.49 |

6.76 0.63 |

7.75 0.51 |

6.89 0.44 |

6.56 0.50 |

10.02 0.67 |

9.24 0.65 |

5.08 0.34 |

5.74 0.39 |

6.77 0.47 |

6.77 0.44 |

6.75 0.47 |

10.73 0.68 |

10.24 0.78 |

| 8.03 0.48 |

6.44 0.66 |

7.45 0.45 |

6.82 0.47 |

6.41 0.41 |

9.77 0.50 |

9.65 0.56 |

4.98 0.34 |

5.58 0.43 |

6.37 0.41 |

6.66 0.50 |

6.64 0.54 |

10.48 0.64 |

9.92 0.72 |

|

|

Iraqis (1979) |

9.03 0.64 |

6.95 0.75 |

8.06 0.60 |

7.17 0.53 |

6.94 0.50 |

10.70 0.60 |

- - |

5.61 0.44 |

6.20 0.50 |

6.97 0.44 |

7.12 0.48 |

7.36 0.57 |

11.26 0.69 |

- - |

| 8.84 0.60 |

6.87 0.69 |

7.84 0.53 |

7.06 0.55 |

6.92 0.53 |

10.62 0.67 |

x x |

5.66 0.45 |

6.19 0.45 |

6.78 0.52 |

7.04 0.61 |

7.28 0.52 |

11.03 0.64 |

x x |

|

|

Bedouins (1979) |

8.76 0.55 |

6.89 0.48 |

7.80 0.49 |

7.02 0.46 |

6.75 0.47 |

10.63 0.58 |

- - |

5.45 0.55 |

6.09 0.48 |

7.03 0.49 |

7.03 0.46 |

7.21 0.47 |

11.27 0.58 |

- - |

| 8.49 0.59 |

6.79 0.63 |

7.49 0.49 |

6.72 0.39 |

6.53 0.59 |

10.22 0.62 |

x x |

5.23 0.33 |

5.88 0.44 |

6.52 0.44 |

6.78 0.40 |

6.92 0.44 |

10.76 0.64 |

x x |

|

|

Yemenites (1979) |

8.06 0.54 |

6.32 0.37 |

7.51 0.66 |

6.88 0.41 |

6.49 0.64 |

10.12 0.63 |

- - |

5.61 0.28 |

6.17 0.41 |

6.49 0.24 |

6.70 0.45 |

6.97 0.64 |

10.83 0.75 |

- - |

| 8.42 0.69 |

6.26 0.85 |

7.28 0.56 |

6.78 0.55 |

6.61 0.52 |

10.44 0.67 |

x x |

5.23 0.43 |

5.62 0.48 |

6.43 0.40 |

6.59 0.64 |

6.98 0.48 |

10.75 0.34 |

x x |

|

|

American Negroes (1975) |

9.12 0.67 |

7.26 0.64 |

8.19 0.53 |

7.66 0.49 |

7.25 0.49 |

11.04 0.64 |

10.74 0.63 |

5.53 0.39 |

6.13 0.44 |

7.37 0.57 |

7.76 0.51 |

7.85 0.55 |

11.76 0.72 |

11.53 0.86 |

| 8.72 0.58 |

7.08 0.56 |

7.74 0.38 |

7.37 0.43 |

6.94 0.39 |

10.57 0.52 |

10.35 0.73 |

5.38 0.39 |

5.99 0.46 |

6.86 0.42 |

7.41 0.50 |

7.61 0.50 |

11.28 0.62 |

10.94 0.73 |

|

|

Americans Southwest (1968) |

8.83 0.58 |

6.73 0.57 |

7.99 0.44 |

7.09 0.44 |

6.78 0.43 |

10.14 0.49 |

9.99 0.60 |

5.44 0.38 |

6.03 0.41 |

6.97 0.38 |

7.21 0.47 |

7.24 0.43 |

11.39 0.63 |

10.69 0.67 |

| 8.58 0.55 |

6.61 0.64 |

7.65 0.42 |

6.93 0.45 |

6.64 0.47 |

9.89 0.54 |

9.69 0.60 |

5.38 0.38 |

5.91 0.39 |

6.59 0.39 |

7.02 0.42 |

7.09 0.51 |

10.96 0.68 |

10.41 0.66 |

|

|

Americans Ohio (1967) |

8.78 0.57 |

6.71 0.58 |

7.95 0.45 |

7.14 0.47 |

6.84 0.46 |

10.17 0.49 |

10.05 0.58 |

5.38 0.38 |

6.02 0.42 |

6.98 0.40 |

7.27 0.47 |

7.26 0.46 |

11.38 0.55 |

10.63 0.62 |

| 8.50 0.57 |

6.47 0.67 |

7.51 0.44 |

6.90 0.40 |

6.60 0.41 |

9.81 0.60 |

9.63 0.61 |

5.31 0.39 |

5.86 0.40 |

6.56 0.41 |

6.99 0.40 |

7.03 0.40 |

10.86 0.67 |

10.18 0.60 |

|

|

Americans Northeast (1957) |

8.78 0.46 |

6.64 0.63 |

7.95 0.42 |

7.01 0.38 |

6.82 0.37 |

10.81 0.56 |

10.35 0.63 |

5.42 0.31 |

5.95 0.38 |

6.96 0.36 |

7.07 0.35 |

7.29 0.52 |

11.18 0.47 |

10.76 0.71 |

| 8.40 0.53 |

6.47 0.62 |

7.53 0.37 |

6.85 0.42 |

6.62 0.43 |

10.52 0.51 |

9.81 0.49 |

5.25 0.36 |

5.78 0.38 |

6.47 0.32 |

6.87 0.38 |

7.02 0.40 |

10.74 0.56 |

10.34 0.62 |

|

| TOOTH | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 |

| Sex | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F | M F |

|

Median Total |

8.75 | 6.89 | 7.98 | 7.17 | 6.83 | 10.50 | 10.00 | 5.46 | 6.03 | 7.01 | 7.17 | 7.22 | 11.17 | 10.53 |

| 8.51 | 6.71 | 7.62 | 7.01 | 6.69 | 10.23 | 9.69 | 5.35 | 5.89 | 6.63 | 7.02 | 7.05 | 10.83 | 10.17 | |

| % Sexual dimorphism | 2.82 | 2.68 | 4.72 | 2.28 | 2.09 | 2.64 | 3.20 | 2.06 | 2.38 | 5.73 | 2.14 | 2.41 | 3.14 | 3.54 |

Table 3. Percentage dimorphism for every tooth and population.

|

Tooth Article |

11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | Total | Ranking | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martins-Filho17 | 2.70 | 3.58 | 4.23 | 3.47 | 4.15 | 4.78 | 2.97 | 3.47 | 2.31 | 4.98 | 3.66 | 3.85 | 1.60 | 3.81 | 3.541 | 14 | Brazilians |

| Khamis et al.28 | 3.98 | 4.26 | 3.74 | 3.34 | 3.68 | 3.09 | 4.45 | 2.56 | 1.49 | 5.39 | 3.01 | 4.00 | 4.20 | 6.61 | 3.842 | 12 | Malaysian Chinese |

| Khamis et al.28 | 3.40 | 1.45 | 3.13 | 1.95 | 2.35 | 2.60 | 3.70 | 2.03 | 3.06 | 5.59 | 1.95 | 2.35 | 2.98 | 2.72 | 2.804 | 21 | Malaysian Tamils |

| Khamis et al.28 | 2.61 | 2.32 | 5.63 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.43 | 2.32 | 2.03 | 1.16 | 6.20 | 1.65 | 0.27 | 2.47 | 2.73 | 2.341 | 28 | Malays |

| Mitsea et al.29 | 3.96 | 0.62 | 3.88 | 0.00 | 1.78 | 7.25 | x | 3.85 | 2.69 | 4.98 | -4.27 | -5.93 | 6.00 | x | 2.066 | 33 | Greeks |

| Angadi et al.30 | 2.39 | 2.56 | 4.39 | 2.32 | 1.52 | 1.98 | 3.58 | 1.12 | 2.06 | 5.72 | 1.01 | 1.72 | 2.43 | 3.43 | 2.588 | 23 | Indians |

| Fernandes et al.1 | 4.87 | 4.84 | 6.86 | 4.38 | 3.80 | 7.24 | x | 6.86 | 6.03 | 8.45 | 5.48 | 7.31 | 5.14 | x | 5.938 | 2 | Brazilian African ancestry |

| Fernandes et al.1 | 3.57 | 0.31 | 3.71 | -0.44 | 0.61 | 2.14 | x | 2.92 | 1.75 | 5.56 | 2.92 | 2.03 | 5.66 | x | 2.562 | 24 | Brazilian Caucasian ancestry |

| Fernandes et al.1 | 2.15 | 6.23 | 3.25 | 2.65 | 1.94 | 1.67 | x | 4.73 | 5.34 | 6.20 | 1.83 | -0.43 | 1.45 | x | 3.085 | 18 | Brazilian Japanese ancestry |

| Thapar et al.4 | 1.19 | 1.52 | 4.00 | 2.99 | 1.56 | 1.30 | 3.13 | -1.85 | 1.72 | 4.62 | -1.43 | 1.47 | 1.89 | 4.14 | 1.874 | 36 | Indians |

| Al-Gunaid et al.31 | 2.76 | 1.56 | 3.70 | 2.93 | 1.77 | 1.32 | x | 1.76 | 2.14 | 4.83 | 1.97 | 1.95 | 3.13 | x | 2.484 | 25 | Yemeni Arabians |

| Castillo et al.27 | 3.35 | 0.15 | -0.25 | 0.97 | 1.45 | -0.29 | x | 0.38 | -1.35 | 1.17 | 0.42 | 1.41 | 2.72 | x | 0.843 | 41 | Colombians |

| Phabhu & Acharya.32 | 1.21 | 2.00 | 2.82 | 1.48 | -1.37 | 1.74 | 2.06 | 2.68 | 2.26 | 2.48 | -0.29 | 2.08 | 2.47 | 0.61 | 1.586 | 37 | Indians |

| Antoszewski et a l.33 | 1.64 | 2.16 | 4.01 | -1.03 | -0.61 | 3.54 | 1.68 | 2.64 | 1.02 | 4.16 | 0.29 | 3.11 | 4.77 | 2.55 | 2.138 | 31 | Polonies |

| Archarya & Mainali8 | 3.17 | 0.88 | 4.47 | 0.57 | 1.23 | 2.51 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 2.02 | 5.78 | 0.85 | -0.85 | 1.37 | 3.65 | 1.950 | 34 | Nepalese |

| Ling & Wong 34 | 1.84 | 2.51 | 4.80 | 2.64 | 2.25 | 3.00 | 3.12 | 0.90 | 1.30 | 6.10 | 2.99 | 2.86 | 3.54 | 3.47 | 2.951 | 19 | Southern Chinese |

| Ngom et al.35 | 3.18 | 12.88 | 5.46 | 2.39 | 2.68 | 1.23 | x | 4.74 | 4.70 | 5.37 | 4.48 | 4.94 | 1.63 | x | 4.474 | 3 | Moroccan |

| Ngom et al.35 | 2.67 | 0.68 | 4.63 | 1.03 | 3.41 | 1.96 | x | 0.36 | 1.63 | 6.20 | 3.76 | 2.73 | -0.89 | x | 2.348 | 27 | Senegalese |

| Ates et al.36 | 1.19 | 3.85 | 5.34 | 1.60 | 1.99 | 1.99 | 1.52 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 5.62 | 1.01 | 1.71 | 1.67 | 0.67 | 2.103 | 32 | Turks |

| Singh & Goyal37 | 4.99 | 1.73 | 3.82 | 2.08 | 5.03 | 3.19 | 3.97 | 2.34 | 5.52 | 5.52 | 5.70 | 5.30 | 3.98 | 3.20 | 4.026 | 7 | North Indians |

| Hashim & Al-Ghamdi38 | 2.09 | 1.80 | 5.44 | 1.60 | 1.25 | 0.60 | x | 2.25 | 2.41 | 5.36 | 1.74 | -1.44 | 3.45 | x | 2.212 | 30 | Saudi Arabia |

| Santoro et al.39 | 2.75 | -0.14 | 3.95 | 2.31 | 1.87 | 2.85 | x | 1.65 | 1.32 | 4.40 | 0.54 | 2.59 | 2.72 | x | 2.233 | 29 | Dominican Americans |

| Lund & Mörnstad6 | 4.72 | 4.96 | 8.54 | 1.63 | 1.20 | 3.97 | 4.63 | 3.01 | 3.22 | 9.60 | 2.01 | 6.36 | 3.06 | 2.94 | 4.274 | 4 | Suécia |

| Yuen & Tang40 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 3.49 | 2.92 | 2.40 | 2.97 | x | -0.90 | -0.49 | 5.35 | 1.88 | 2.20 | 1.35 | x | 1.901 | 35 | Hong Kong |

| Hattab et al.41 | 3.81 | 4.02 | 5.47 | 2.42 | 2.19 | 3.12 | x | 2.35 | 2.30 | 4.99 | 5.12 | 3.35 | 4.15 | x | 3.608 | 13 | Jordanians |

| Hashim & Murshid42 | -0.35 | 2.89 | 5.83 | 2.34 | 0.15 | 1.05 | x | -0.74 | -0.17 | 4.62 | -2.13 | 0.42 | 1.47 | x | 1.282 | 39 | Saudi Arabians |

| Lukacs & Hemphill43 | 4.38 | 5.13 | 5.27 | 1.74 | 1.72 | 3.60 | 4.24 | 1.70 | 2.58 | 7.15 | 1.89 | 2.02 | 3.03 | 2.47 | 3.353 | 16 | Northwest India/Bhils |

| Lukacs & Hemphill43 | 4.11 | 3.55 | 4.37 | 1.96 | 2.38 | 3.50 | 6.70 | 2.32 | 3.35 | 6.85 | 2.26 | 3.93 | 4.55 | 4.00 | 3.845 | 11 | Northwest India/Rajputs |

| Lukacs & Hemphill43 | 2.40 | 4.02 | 5.36 | 3.87 | 3.18 | 2.93 | 2.93 | 2.12 | 3.13 | 7.21 | 2.07 | 1.91 | 3.13 | 4.93 | 3.513 | 15 | Northwest India/Garasias |

| Bishara et al.44 | 1.18 | 1.52 | 4.00 | 2.99 | 3.08 | 3.96 | x | 3.85 | 2.61 | 6.25 | 1.47 | 2.94 | 5.77 | x | 3.300 | 17 | Americans |

| Bishara et al.44 | 2.44 | 1.54 | 3.95 | 4.55 | 6.06 | 3.43 | x | 1.85 | 3.45 | 6.98 | 4.48 | 4.29 | 3.81 | x | 3.901 | 10 | Mexican |

| Bishara et al.44 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 5.33 | 0.00 | 1.49 | 1.46 | x | -2.70 | -1.67 | 4.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | x | 0.828 | 42 | Egyptians |

| Kieser et al.45 | 6.43 | 7.93 | 8.91 | 4.01 | 6.39 | 4.47 | 7.10 | 3.94 | 3.16 | 8.10 | 5.21 | 5.83 | 6.25 | 5.88 | 5.972 | 1 | South Africa Caucasoid |

| Axelsson & Kirveskari46 | 2.74 | 1.76 | 4.49 | 2.12 | 0.73 | 2.62 | 3.07 | 2.01 | 2.99 | 4.85 | 2.53 | 2.48 | 2.97 | 3.43 | 2.770 | 22 | Icelanders |

| Potter et al.47 | 3.74 | 4.97 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 2.34 | 2.56 | -4.25 | 2.01 | 2.87 | 6.28 | 1.65 | 1.66 | 2.39 | 3.23 | 2.463 | 26 | Filipinos |

| Ghose & Baghdady48 | 2.15 | 1.16 | 2.81 | 1.56 | 0.29 | 0.75 | x | -0.88 | 0.16 | 2.80 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 2.09 | x | 1.260 | 40 | Iraqis |

| Ghose & Baghdady48 | 3.18 | 1.47 | 4.14 | 4.46 | 3.37 | 4.01 | x | 4.21 | 3.57 | 7.82 | 3.69 | 4.19 | 4.74 | x | 4.071 | 6 | Bedouins |

| Ghose & Baghdady48 | -4.28 | 0.96 | 3.16 | 1.47 | -1.82 | -3.07 | x | 7.27 | 9.79 | 0.93 | 1.67 | -0.14 | 0.74 | x | 1.391 | 38 | Yemenites |

| Richardson & Malhotra49 | 4.59 | 2.54 | 5.81 | 3.93 | 4.47 | 4.45 | 3.77 | 2.79 | 2.34 | 7.43 | 4.72 | 3.15 | 4.26 | 5.39 | 4.260 | 5 | American Negroes |

| Garn et al.50 | 2.91 | 1.82 | 4.44 | 2.31 | 2.11 | 2.53 | 3.10 | 1.12 | 2.03 | 5.77 | 2.71 | 2.12 | 3.92 | 2.69 | 2.826 | 20 | Americans/Southwest |

| Garn et al.13 | 3.29 | 3.71 | 5.86 | 3.48 | 3.64 | 3.67 | 4.36 | 1.32 | 2.73 | 6.40 | 4.01 | 3.27 | 4.79 | 4.42 | 3.925 | 9 | Americans/Ohio |

| Moorrees et al.51 | 4.52 | 2.63 | 5.58 | 2.34 | 3.02 | 2.76 | 5.50 | 3.24 | 2.94 | 7.57 | 2.91 | 3.85 | 4.10 | 4.06 | 3.930 | 8 | Americans/Northeast |

| Total | 2.74 | 2.71 | 4.64 | 2.3 | 2.15 | 2.64 | 3.22 | 2.04 | 2.45 | 5.64 | 2.14 | 2.37 | 3.09 | 3.51 | 2.74 | ||

| Ranking | 6 | 7 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 5 | 3 | total |

The selected studies generally focused on young adults; deterioration factors such as tooth wear, mainly for mesiodistal diameters of the crown, had a very important effect that reduced the number of teeth recorded, affecting >50% of the measures for some teeth. (53)

The greater dimensions of masculine canines are the consequences of differing enamel thickness, due to the longer period of amelogenesis in males. (4) Our results confirm that canines reflect the greatest sexual dimorphism: approximately 0.3585-0.3974 mm for lower canines and 0.3368-0.3814 mm for upper canines (Table 4); however, the second molars were not reported by other specific studies in this area. (30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 50) Notably, we found great differences in values: 0.3259-0.4041 mm for lower second molar and 0.2667-0.3452 mm for upper second molar (Table 4). Of the studies selected for this systematic review, only 23 measured second molars, which indicates that the authors did not focus on the analysis of these teeth.

In the data ranking (Table 4), the teeth with the greatest mesiodistal crown sexual dimorphism were the lower canines, followed in order by the lower second molars, upper canines, and upper second molars. Several studies reported canines and first molars to be the most diffuse teeth with the greatest variation in morphology between male and female subjects. (32, 33, 35, 38, 44, 48, 50) Other studies found significant differences in central and/or lateral teeth. (1, 6, 27-30, 38) We found it in fifth and sixth ranking. Some studies reported that the premolars exhibited sexual dimorphism, (6, 30, 31, 35, 37, 40, 43, 44, 47, 49, 51) while some studies reported the opposite. (1, 8, 29, 32, 33, 35, 48) Our results did not verify findings of sexual dimorphism. In both upper premolars and the first lower premolar, the differences were <2.3%.

Anatomical variation among populations is normal; (14, 55) however, we cannot explain why only upper second molars and lower first premolars exhibited substantial heterogeneity (Table 5), although Egger's test showed no publication bias.

The crowns of premolar teeth showed the smallest dimorphism between males and females throughout the population studied. Linear measurement with extractions of premolar permanent teeth will be very similar between men and women (Table 2). However, measurements of the crowns of the remaining canines and molars should serve to determine an appropriate treatment plan and achieve greater stability in orthodontic planning, in addition to calculating these different forces in relation to the dental crown. (2) This implies important considerations of this study for this aspect. The measurement of the dental crowns is important for orthodontic forces and anchorage; (1, 2) notably, the movement of the tooth as a whole will be realized. (11) Use of the second molar, when possible, for anchorage is a viable alternative to conventional molar anchorage. (56)

The differences between populations in the mesiodistal crowns are very large, even when considering all teeth (Table 4), which shows the fragility of this measurement with respect to sexual dimorphism. The total amounts range from 5.97% to 0.82% for all teeth. This cannot be fully explained by anatomical variables; factors such as genetics and environmental are closely related. (29, 54) Some researchers suspect that the analyses for mesiodistal measurements should discriminate sex better than those for buccolingual dimensions; however, these measurements are lower than those derived by combining both dimensions. (8, 57) However, our results showed the opposite; the difference between the sexes in all populations varied greatly, but this variation was insufficient to be considered a single method of differentiation between the sexes, with respect to teeth.

Most current articles regarding dental anatomy work with 3D technologies, (5, 10, 11) exceeding the accuracy of the results attained in our systematic review. However, the idea of working solely with mesiodistal measures was to provide an easy technique that could be reproduced in practice without sophisticated equipment. (29, 53) For forensic experts, our study shows that using measurements of canine crowns and second molars will help in the identification of human remains to determine sex and age, even in cases where skeletal remains are damaged or destroyed. (4) However, mesiodistal crowns do not exhibit sufficient evidence of sexual dimorphism among the populations and probably should not be the sole method used.

LIMITATION OF STUDY:

The study was unable to identify differences between the populations; the data collected do not allow this inference.

Most current articles work with 3D technologies, thus exceeding the accuracy of the results attained in our systematic review.

The studies concentrated on either mesiodistal or buccolingual dimensions, or both. We focused on mesiodistal measurements; some important information may have been lost as a result.

Finally, we included studies conducted in different areas, which utilized different data collection techniques. Nevertheless, similar results were recorded across these studies.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that a small degree of sexual dimorphism exists in all human teeth. The second molars and canines show the greatest sexual dimorphism. Our results also indicate that this dental dimorphism occurs among different racial groups living in different geographic areas; however, it is not possible to establish a single value applicable to all populations.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Scientific rational for study

For forensic dentistry, this study supports other studies in the area using canines and second molars, as well as other cranial measurements for the post-mortem detection of sex; it supports the establishment of patterns that can be used across populations.

Practical implications

For forensic experts, our study shows that using measurements of canine crowns and second molars may help in the identification of remains for post-mortem determination of sex and age, along with other cranial measurements.

For orthodontics, premolars exhibit little mesiodistal difference between the sexes; however, orthodontic forces differ between males and females.

For prosthetics, use of the mesiodistal measurements of crowns for making prostheses (implant supported or not) that follow the mean values found in the populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the University of São Paulo librarians for helping to find some difficult papers and the reviewers for improving this work.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fernandes TM, Sathler R, Natalício GL, Henriques JF, Pinzan A. Comparison of mesiodistal tooth widths in Caucasian, African and Japanese individuals with Brazilian ancestry and normal occlusion. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013. May-Jun;18(3):130–5. 10.1590/S2176-94512013000300021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee B. The dimensions of the roots of the human permanent dentition as a guide to the selection of optimal orthodontic forces. Aust Orthod J. 2010. May;26(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doris JM, Bernard BW, Kuftinec MM, Stom D. A biometric study of tooth size and dental crowding. Am J Orthod. 1981. Mar;79(3):326–36. 10.1016/0002-9416(81)90080-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thapar R, Angadi PV, Hallikerimath S, Kale AD. Sex assessment using odontometry and cranial anthropometry: evaluation in an Indian sample. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2012. Jun;8(2):94–100. 10.1007/s12024-011-9247-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinchi V, Pradella F, Buti J, Baldinotti C, Focardi M, Norelli GA. A new age estimation procedure based on the 3D CBCT study of the pulp cavity and hard tissues of the teeth for forensic purposes: A pilot study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2015. Nov;36:150–7. 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund H, Mörnstad H. Gender determination by odontometrics in a Swedish population. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 1999. Dec;17(2):30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moorrees CF, Reed RB. Correlations among crown diameters of human teeth. Arch Oral Biol. 1964. Nov-Dec;9:685–97. 10.1016/0003-9969(64)90080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya AB, Mainali S. Univariate sex dimorphism in the Nepalese dentition and the use of discriminant functions in gender assessment. Forensic Sci Int. 2007. Nov 15;173(1):47–56. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adler CJ, Donlon D. Sexual dimorphism in deciduous crown traits of a European derived Australian sample. Forensic Sci Int. 2010. Jun 15;199(1-3):29–37. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Angelo L, Di Stefano P, Bernardi S, Continenza MA. A new computational method for automatic dental measurement: The case of maxillary central incisor. Comput Biol Med. 2016. Mar 1;70:202–9. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Li H, Zhao T, Gao Y, Guo J, Wang X, et al. Crown-to-root ratios in terms of length, surface area and volume: A pilot study of premolars. Int J Morphol. 2016;34(2):465–70. 10.4067/S0717-95022016000200009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettenati-Soubayroux I, Signoli M, Dutour O. Sexual dimorphism in teeth: discriminatory effectiveness of permanent lower canine size observed in aXVIIIth century osteological series. Forensic Sci Int. 2002. May 23;126(3):227–32. 10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00080-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garn SM, Lewis AB, Swindler DR, Kerewsky RS. Genetic control of sexual dimorphism in tooth size. J Dent Res. 1967. Sep-Oct;46(5):963–72. 10.1177/00220345670460055801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yammine K. Evidence-based anatomy. Clin Anat. 2014. Sep;27(6):847–52. 10.1002/ca.22397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garn SM, Lewis A, Kerewsky R. Buccolingual size asymmetry and its developmental meaning. Angle Orthod. 1967. Jul;37(3):186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieser JA, Groeneveld HT. The unreliability of sex allocation based on human odontometric data. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 1989. Jun;7(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins-Filho IE. Relationship between gender and tooth measures: a Brazilians study (thesis). São Paulo (Brazil): Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Odontologia; 2013 (cited 2015 Oct 10).Available from: (http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/23/23153/tde-04112013-145957/pt-br.php). Portuguese.

- 18.Jofré CA, Jaime SPV, Iván SG. Sexual dimorphism in the tooth dimensions of Spanish and Chilean peoples. Int J Odontostomatol. (Print). 2009;3(1):41–50. [Spanish.] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair P, Rao BB, Anniger RG. A study of tooth size, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism. Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology. 1999;16(2):10–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suazo GI, Cantin LM, López FB, Sandoval MC, Torees MS, Gajardo RP, et al. Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal and buccolingual tooth dimensions in Chilean people. Int J Morphol. 2008;26(3):609–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakash S, Kaul V, Kanta S. Observations on Bhutanese dentition. Hum Biol. 1979;51(1):23–30, 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumura H, Hudson MJ. Dental perspectives on the population history of Southeast Asia. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;127(2):182–209. 10.1002/ajpa.20067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuen KK, Tang EL, So LL. Relations between the mesiodistal crown diameters of the primary and permanent teeth of Hong Kong Chinese. Arch Oral Biol. 1996. Jan;41(1):1–7. 10.1016/0003-9969(95)00107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doris JM. Doris, Bernard BW, Kuftinec MM, Stom D. A biometric study of tooth size and dental crowding. Am J Orthod. 1981. Mar;79(3):326–36. 10.1016/0002-9416(81)90080-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brosco HB, de Souza-Freitas JA, Mazzottini R, Abdo RC, Damante JH, Bonfante G. [Efficacy and applicability of some odontometric methods (author's transl)]. Estomatol Cult. 1975. Jul-Dec;9(2):203–12. [Portuguese.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garn SM, Lewis AB, Kerewsky RS, Jegart K. Sex differences in intraindividual tooth-size communalities. J Dent Res. 1965. May-Jun;44:476–9. 10.1177/00220345650440030601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castillo L, Castro AM, Lerma C, Lozada D, Moreno F. Mesiodistal and buccolingual dental diameters in a group of mixed ethnicity population in Cali, Colombia. Rev Estomat. 2011;19(2):16–22. [Spanish.] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khamis MF, Taylor JA, Malik SN, Townsend GC. Odontometric sex variation in Malaysians with application to sex prediction. Forensic Sci Int. 2014. Jan;234:183.e1. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitsea AG, Moraitis K, Leon G, Nicopoulou-Karayianni K, Spiliopoulou C. Sex determination by tooth size in a sample of Greek population. Homo. 2014. Aug;65(4):322–9. 10.1016/j.jchb.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angadi PV, Hemani S, Prabhu S, Acharya AB. Analyses of odontometric sexual dimorphism and sex assessment accuracy on a large sample. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013. Aug;20(6):673–7. 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Gunaid T, Yamaki M, Saito I. Mesiodistal tooth width and tooth size discrepancies of Yemeni Arabians: A pilot study. J Orthod Sci. 2012. Apr;1(2):40–5. 10.4103/2278-0203.99760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prabhu S, Acharya AB. Odontometric sex assessment in Indians. Forensic Sci Int. 2009. Nov 20;192(1-3):129.e1. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoszewski B, Zadzińska E, Foczpański J. The metric features of teeth in female-to-male transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 2009. Jun;38(3):351–8. 10.1007/s10508-008-9315-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling JY, Wong RW. Tooth dimensions of Southern Chinese. Homo. 2007;58(1):67–73. 10.1016/j.jchb.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngom PI, Diagne F. IdrissiOuedghiri D, IdrissiOuedghiri H. (Comparative odontometric data between Moroccan and Senegalese). Odontostomatol Trop. 2007. Mar;30(117):17–25. [French.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ateş M, Karaman F, Işcan MY, Erdem TL. Sexual differences in Turkish dentition. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2006. Oct;8(5):288–92. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh SP, Goyal A. Mesiodistal crown dimensions of the permanent dentition in North Indian children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006. Dec;24(4):192–6. 10.4103/0970-4388.28076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashim HA, Al-Ghamdi S. Tooth width and arch dimensions in normal and malocclusion samples: an odontometric study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005. May 15;6(2):36–51. 10.5005/jcdp-6-2-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santoro M, Ayoub ME, Pardi VA, Cangialosi TJ. Mesiodistal crown dimensions and tooth size discrepancy of the permanent dentition of Dominican Americans. Angle Orthod. 2000. Aug;70(4):303–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuen KK, So LL, Tang EL. Mesiodistal crown diameters of the primary and permanent teeth in southern Chinese a longitudinal study. Eur J Orthod. 1997. Dec;19(6):721–31. 10.1093/ejo/19.6.721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hattab FN, al-Khateeb S, Sultan I. Mesiodistal crown diameters of permanent teeth in Jordanians. Arch Oral Biol. 1996. Jul;41(7):641–5. 10.1016/S0003-9969(96)00066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashim HA, Murshid ZA. Mesiodistal tooth width. A comparison between Saudi males and females.Part 1. Egypt Dent J. 1993. Jan;39(1):343–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukacs JR, Hemphill BE. Odontometry and biological affinity in south Asia: analysis of three ethnic groups from northwest India. Hum Biol. 1993. Apr;65(2):279–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Abdallah EM, Fernandez Garcia A. Comparisons of mesiodistal and buccolingual crown dimensions of the permanent teeth in three populations from Egypt, Mexico, and the United States. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989. Nov;96(5):416–22. 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90326-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kieser JA, Groeneveld HT, Preston CB. A metric analysis of the South African Caucasoid dentition. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1985. Mar;40(3):121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Axelsson G, Kirveskari P. Crown size of permanent teeth in Icelanders. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983. Jun;41(3):181–6. 10.3109/00016358309162321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potter RH, Alcazaren AB, Herbosa FM, Tomaneng J. Dimensional characteristics of the Filipino dentition. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1981. May;55(1):33–42. 10.1002/ajpa.1330550106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghose LJ, Baghdady VS. Analysis of the Iraqi dentition: mesiodistal crown diameters of permanent teeth. J Dent Res. 1979. Mar;58(3):1047–54. 10.1177/00220345790580030301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson ER, Malhotra SK. Mesiodistal crown dimension of the permanent dentition of American Negroes. Am J Orthod. 1975. Aug;68(2):157–64. 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90204-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garn SM, Lewis AB, Walenga AJ. Maximum-confidence values for the human mesiodistal crown dimension of human teeth. Arch Oral Biol. 1968. Jul;13(7):841–4. 10.1016/0003-9969(68)90107-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moorees CFA, Thosen SO, Jensen E, Kai-Jen Yen P. Mesiodistal crown diameters of the deciduous and permanent teeth in individuals. J Dent Res. 1957.Feb;36(1):39-47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Diop Ba K, Diagne F, Diouf JS, Ndiaye R, Diop F. Odontometric data in a senegalese population: comparison between the manual method and digital analysis. Int Orthod. 2008. Sep;6(3):285–99. [English, French.] 10.1016/S1761-7227(08)75164-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hunter WS, Priest WR. Errors and discrepancies in measurement of tooth size. J Dent Res. 1960. Mar-Apr;39:405–14. 10.1177/00220345600390022301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luna LH. Interpretative potential of dental metrics for biodistance analysis in hunter-gatherers from central Argentina. A theoretical-methodological approach. Homo. 2015. Oct;66(5):432–47. 10.1016/j.jchb.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henry BM, Tomaszewski KA, Walocha JA. Methods of evidence-based anatomy: a guide to conducting systematic reviews and meta-analysis of anatomical studies. Ann Anat. 2016. May;205:16–21. 10.1016/j.aanat.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nienkemper M, Wilmes B, Pauls A, Yamaguchi S, Ludwig B, Drescher D. Treatment efficiency of mini-implant-borne distalization depending on age and second-molar eruption. J Orofac Orthop. 2014. Mar;75(2):118–32. 10.1007/s00056-013-0199-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Acharya AB, Mainali S. Sex discrimination potential of buccolingual and mesiodistal tooth dimensions. J Forensic Sci. 2008. Jul;53(4):790–2. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]