Abstract

Background

To investigate the molecular mechanisms determining the coat color of native breed sheep in Xinjiang.

Methods

Bashibai sheep, Yemule white sheep and Tulufan black sheep were selected. Illumina HiSeq X Ten sequencing technology was used to detect the genes responsible for the white, light brown, black and cyan gray coat colors in sheep. Sequence analysis and functional gene annotation analysis were performed to analyze the results. The signal pathways and differentially expressed genes related to sheep hair color production regulation were screened and finally verified by real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Functional annotation by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis revealed significant differences in enrichment of immunity-related pathways as well as melanogenesis synthetic and tyrosine metabolism pathways. Our results showed that the DCT, TYR, TYRP1, PMEL, SLC45A2 and MLANA six genes may be associated with the regulation of coat color development and provide a theoretical basis for selecting natural coat colors of sheep.

Keywords: Sheep, RNA-seq, Molecular mechanism, Coat color

Introduction

The sheep were one of the earliest domesticated animals worldwide and the wool of sheep is an important textile material. Chinese sheep colors mainly include red brown, yellow brown, black, white, spotted and other colors, which are determined by both genetics and the environment. In several vertebrates, the colors of the eyes, feathers and skin are primarily determined by the amount and distribution of melanin, which is secreted by mature melanocytes at the base of the epithelium (Simon et al., 2009; Cieslak et al., 2011). There are two types of melanin: pheomelanin, which is a round red particle dissolved in alkali environments and causes a yellow and red coat color and eumelanin, including black and brown pigment types, the ratio of which determines the animal coat color phenotype (Yue et al., 2015; Visscher, 2017). Melanocytes are derived from the embryonic neural crest and melanoblast specification and migration as well as melanocyte differentiation depend on the regulation of different genes. After the binding of melanocortin one receptor (MC1R) on the cell membrane to melatonin (α-MSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone, the coupled G protein is converted to GTP, thereby activating the adenylate ring on the membrane. The enzyme system produces cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and further activates the tyrosine (TYR) kinase, which, in turn, activates TYR to participate in melanin synthesis. Under normal conditions, melanocytes synthesize pheomelanin; otherwise, under conditions of excessive activation of TYR, they synthesize eumelanin (Abdel-Malek et al., 1995; Suzuki et al., 1996; Marklund et al., 1996). MC1R is antagonized by agouti signaling protein (ASIP), which competes with α-MSH for binding to MC1R. ASIP binds to MC1R to block the initiation signal of α-MSH, which blocks the production of cAMP, ultimately leading to increased synthesis of eumelanin and decreased synthesis of pheomelanin (Jackson et al., 2006).

The number of white sheep is the largest in the world as their coat can be dyed to virtually any color. In Xinjiang, the local sheep have four coat colors. Previous studies have identified two alleles at the extension locus in sheep: the dominant black allele (ED), which accounts for the black pigmentation of colored breeds and the wild type allele (E+), which is widely distributed in most breeds (Våge et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2013; Mahmoud et al., 2017) and has also been observed in 13 breeds of sheep in China (Yang et al., 2013). Significant associations between these alleles and coat color were found within or near the ASIP, ITCH, AHCY and RALY genes on chromosome 13 for black and brown coat colors and the KIT and PDGFRA genes on chromosome six for white coat color using genome-wide association studies in Markhoz (Nazari-Ghadikolaei et al., 2018). A regulatory mutation identified in the ASIP gene was associated with the black recessive non-agouti (Aa) allele (Norris & Whan, 2008; Gratten et al., 2010). In addition, two mutations in ASIP (recessive black allele: g.100_105del (D5) and/or g.5172T>A) were associated with black coat color in Klövsjö and Roslag sheep breeds and in MC1R (dominant black allele: c.218T>A and/or c.361G>A) were associated with black coat color in Swedish Finewool sheep (Rochus et al., 2019).

There are approximately 26 million sheep in Xinjiang, China, with rich and varied coat colors, some of which have four or more coat color phenotypes. Local varieties mostly have coarse wool, which is difficult to utilize and thus, these sheep are mostly used for meat production. However, Xinjiang local sheep produce 1.2–1.9 kg of wool per year per sheep, with a cashmere content of 55.5–58.5%, which can be used as a textile material. Based on the cashmere fitness and length, the four phenotypes of the coat are in the order of light brown > black > cyan gray > white, with cashmere fineness of 20.94 ± 4.03 μm and length of 14.03 ± 1.4 cm for light brown; 20.45 ± 4.13 μm and 20.2 ± 1.6 cm for black; 21.49 ± 4.40 μm and 15.2 ± 1.8 cm for cyan gray; and 21.21 ± 4.51 μm and 19.14 ± 2.6 cm for white. Therefore, understanding the regulation mechanism of wool color determination of local breeds of sheep in Xinjiang is important. In this study, four types of wool color phenotypes observed in sheep in Xinjiang were conducted transcriptome sequencing to analyze the differentially expressed genes. These results provide molecular theoretical basis for breeding sheep with different wool colors.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-six healthy 1-year-old white (Yemule white sheep), black (Tulufan black sheep), light brown and cyan gray (Bashibai sheep) ewe (nine sheep per color) were selected for sample collection from a sheep farm in Xinjiang. Local anesthesia to decrease animal suffering was performed with procaine hydrochloride (1.5 mL, 3%) after obtaining approval (reference number 2018004) to conduct the study from the Animal Hospital of Xinjiang Agricultural University. Two pieces of skin (10 mm in diameter) from the scapular area were collected and immediately placed into liquid nitrogen. Three sheep skin tissues of each color were subjected to sequencing. Light brown skin sample numbers were R1, R2 and R3; black skin sample numbers were B1, B2 and B3; cyan gray skin sample numbers were G1, G2 and G3; and white skin sample numbers were W1, W2 and W3. Total RNA from samples was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing libraries were generated using the NEBNext Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. To select cDNA fragments of approximately 240 base pairs in length, the library fragments were purified with the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Next 3 μL USER Enzyme (New England Biolabs) was added to size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA at 37 °C for 15 min followed by 5 min at 95 °C before PCR.

Quality control of sequencing data

Library sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten (San Diego, CA, USA). The raw data file obtained by high-throughput sequencing was transformed into the original sequencing data after base recognition analysis. Fast QC software was used for evaluating sequenceing quality (QC) and then the reads containing adapters, high N contents, or numerous low-quality bases were filtered out to obtain clean reads. Hisat2 tools were used to map the reads to the reference genome (Nazari-Ghadikolaei et al., 2018). StringTie (Pertea et al., 2015) was used to splice the alignment results of Hisat2 and the type of alternative splicing and the corresponding expression amount of each sample were obtained by ASprofile (Florea, Song & Salzberg, 2013) software. The sequencing data of 12 samples were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (Black group: SRR10143190, SRR10143189, SRR10143186, Cyan gray group: SRR10143185, SRR10143184, SRR10143183, Light brown group: SRR10143182, SRR10143181, SRR10143180, White group: SRR10143188, SRR10143187, SRR10143179) in NCBI.

Differential expression analysis

Transcription levels were calculated using the fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) method. Using DESeq (Love, Huber & Anders, 2014) software to analyze the differential expression between sample groups, two different expression gene sets between biological conditions were obtained and a fold-change ≥2 and false discovery rate <0.05 were set as the threshold for significant differential expression. The fold-change indicates the ratio of the expression levels between the two groups. DESeq provide statistical routines for determining differential expression in digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 found by DESeq were assigned as differentially expressed.

Gene function annotation

Gene function was annotated using the following databases: NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (Nr) (Deng et al., 2006), NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequences (Nt), Protein family (Pfam) (Finn et al., 2014), KOG, Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) (Tatusov et al., 2000; Koonin et al., 2004), Swiss-Prot (A manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG Ortholog database) and Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000).

Quantitative real-time PCR validation

Differentially expressed genes related to coat color were selected. Referring to the sequences of these genes in sheep published in GenBank, specific primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software and synthesized by Bioengineering (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. (Table S1). The relative expression of genes was statistically analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCt method, statistical analysis was performed using student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Results

Data quality control

The base content and base mass distribution statistics of clean reads were obtained by quality control of sequencing data (Figs. S1 and S2). The effective GC ratio was above 51%. Quality value Q 30 means that the base recognition accuracy rate is 99.9%, which is above 94% and that the ratio of each sample aligned to reference genome was 89.69–90.29% (Table S2). Additionally, most read were mapped to the EXON region (Fig. S3), which overall indicates good sequencing data and high utilization. A total of 12 types of variable shear were found in the results of variable splicing analysis, the most important of which were: variable 1st exon (alternative first exons, TSS), variable end exon (alternative last exons, TTS), single exon jumps (skipped exons, SKIP), and variable 5′ or 3′ end shear (alternative exon ends 5′, 3′, or both).

Analysis of differentially expressed genes

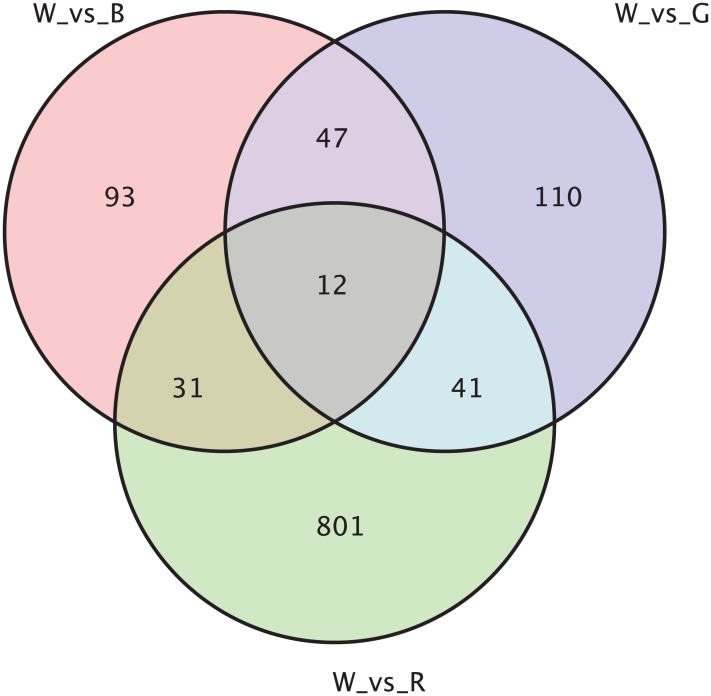

According to the level of gene expression (FPKM), a fold-change ≥2 and false discover rate <0.05 were used as screening criteria. The FPKM box plot of each sample was drawn (Fig. S4) and the gene expression levels of individual samples were distributed at the same expression level. The overall expression levels of the samples were also nearly identical. Additionally, the clustering maps of differentially expressed genes in each group were drawn (Fig. S5). Each group of samples was clustered together and three samples from the same group were clustered in some cluster. Sequence alignments were performed using the NR, GO, COG, KOG and KEGG databases and differences in gene expression among the four color phenotype groups were calculated (Table 1). The white sheepskin was used as the control group and the other three were used as comparison groups (W_vs_B, W_vs_G, W_vs_R). A total of 183 significantly differentially expressed genes in the white and black groups, and 91 up-regulated genes and 92 down-regulated genes in the black group were observed. There were 210 significantly differentially expressed genes in the white and cyan gray group, 56 up-regulated genes and 154 down-regulated genes in the cyan gray group, 885 differentially expressed genes in the white and light brown groups, 584 up-regulated genes and 301 down-regulated genes in the light brown group. Additionally, the number of differentially expressed genes in the three groups was counted and plotted as a Venn diagram to show the number of unique and differentially expressed genes between groups (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Differentially expressed genes annotation by searching against public databases.

| Group | NR | COG | KOG | GO | KEGG | DEGs-total | DEGs-up | DEGs-down |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W_vs_B | 179 | 55 | 82 | 147 | 118 | 183 | 91 | 92 |

| W_vs_G | 209 | 56 | 97 | 176 | 154 | 210 | 56 | 154 |

| W_vs_R | 851 | 207 | 411 | 661 | 558 | 885 | 584 | 301 |

Figure 1. Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes.

GO, COG, KOG and KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

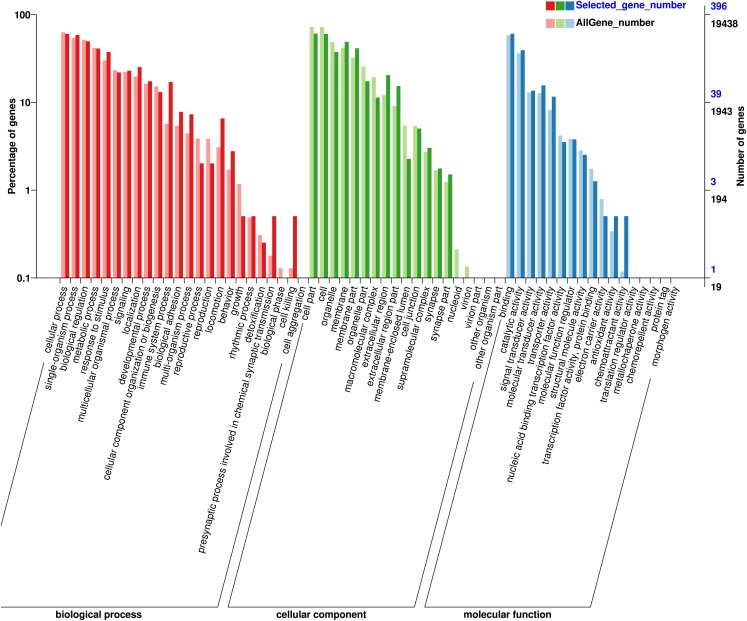

GO annotation analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes in the four groups and GO entries with corresponding gene numbers >2 in the three classifications were screened, including 23 biological processes (BP), 14 cellular components (CC) and 12 molecular functions (MF). In the BP functional classification, the annotated genes were mainly classified into cellular process, single-organism process and biological regulation. In the CC function classification, most annotated genes were mainly classified into cell, cell part and organelle; in the MF function classification, most annotated genes were classified as having binding activity, catalytic activity and signal transducer activity (Fig. 2). Among the three comparison groups, coat color genes were routinely classified into some general functions: melanocyte differentiation (GO:0030318), melanosome transport (GO:0032402), developmental pigmentation (GO:0048066), melanin biosynthetic process (GO:0042438) and melanosome (GO:0042470). The expression levels of six of the aforementioned coat color genes were detected in sheep skin in the present study.

Figure 2. GO analysis of differentially expressed genes.

The abscissa is the GO classification, left ordinate is the percentage of the number of genes and right ordinate is the number of genes. This figure shows the gene enrichment of each secondary function of GO in the background of differentially expressed genes and of all genes, reflecting the status of each secondary function in the two backgrounds. The difference in the proportion of secondary functions indicates that the enrichment trend of differentially expressed genes differs from that of all other genes.

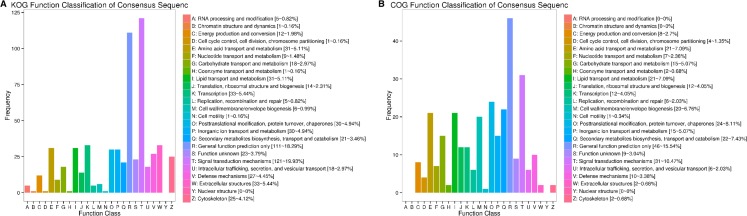

KOG annotation analysis of comparative groups of differential expression genes (Fig. 3A) showed that the main functions of homologous proteins of differentially expressed genes were concentrated in T: signal conduction mechanism (121–19.93%); R: general function (111–18.29%); and K: Transciption (33–5.44%). COG annotation analysis of differentially expressed genes between groups (Fig. 3B) showed that gene expression protein function was mainly concentrated in R: general function (46–15.54%); T: signal conduction mechanism (31–10.47%); and O: Posttranslational modification (24–8.11%).

Figure 3. KOG and COG analysis of differentially expressed genes.

(A) KOG analysis of differentially expressed genes, (B) COG analysis of differentially expressed genes.

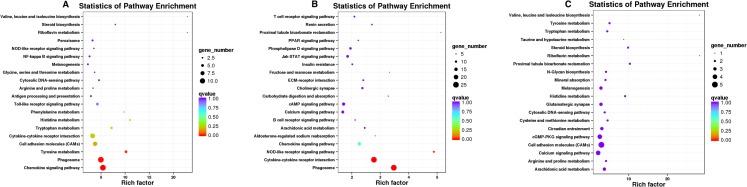

KEGG annotation analysis of differentially expressed genes between groups (Fig. 4) showed that the differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in pathways associated with immunomodulation, chemokine, cell adhesion molecules, Toll-like receptor, NF-κ B, melanogenesis and melanin metabolism and TYR metabolism and finally, six differentially expressed genes related to coat color generation including DCT, TYR, TYRP1, PMEL, SLC45A2 and MLANA, were identified.

Figure 4. KEGG analysis of differentially expressed genes.

(A) W_vs_G, (B) W_vs_R, (C) W_vs_B. Each circle in the figure represents a KEGG pathway and the vertical coordinate represents the name of the pathway while the horizontal coordinate is the enrichment factor, which is the ratio of the number of genes annotated to a certain pathway in differential genes and number of genes annotated to the pathway in all genes. A greater enrichment factor indicates a more significant enrichment level of differentially expressed genes in this pathway. The color of the circle represents q-value and the q-value is p value after multiple hypothesis testing and correction. A smaller q-value indicates a more reliable is the enrichment significance of differentially expressed genes in this pathway. The size of the circle indicates the number of genes enriched in the pathway and a larger circle indicates a greater number of genes.

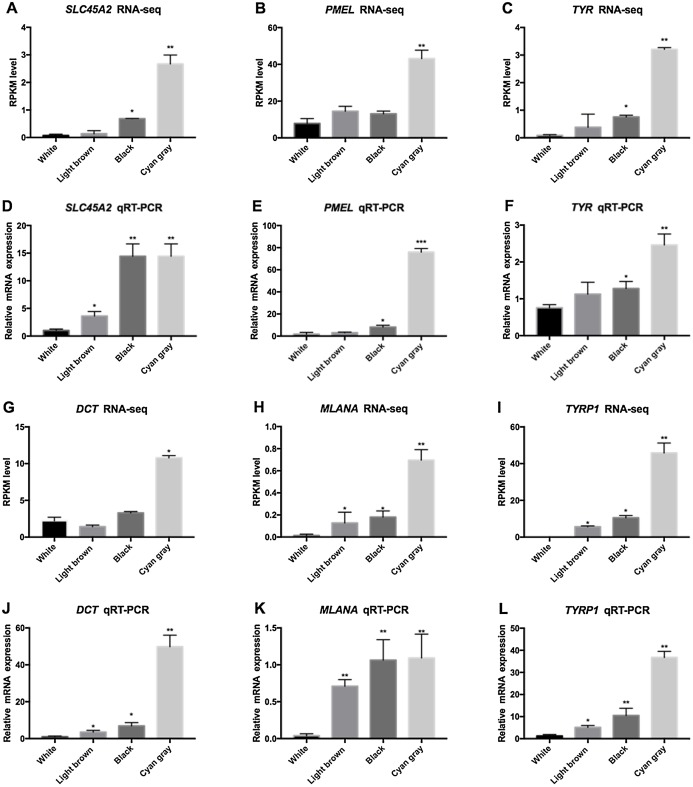

Relative quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Six color-related differentially expressed genes (DCT, TYR, TYRP1, PMEL, SLC45A2, MLANA) were screened for gene expression validation in the four sheep groups by real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (Fig. 5). The results showed that the expression of these six genes in the cyan gray group was higher than that in the black group and the expression trend was consistent with the sequencing results of the transcriptome, indicating the reliability of the sequencing results.

Figure 5. DEGS of qRT-PCR verification analysis.

(A–C, G–I) The FPKM values for the six genes selected for this study. The FPKM values are indicated on the y-axis, and gene names are indicated on the x-axis. (D–F, J–L) The qRT-PCR for the 6 genes selected for this study. The Relative expression of six genes on the y-axis, and gene names are indicated on the x-axis.

Discussion

Most mammals have two or more coat colors, which are determined by two pigments on the skin surface. Coat color is an important phenotype in sheep, as it can affect the economic value of the wool. Melanin is produced by various proteins during melanosome development. Melanosomes are organelles in melanocytes that can synthesize and transport melanin (Cieslak et al., 2011).

The premelanosome protein (PMEL) is a precursor protein of melanin and important component of the small-molecular weight melanin. It is closely related to the production and deposition of melanin and plays an important role in the synthesis of melanin. Previous studies have shown that PMEL gene was related to the silver phenotype. In Bos taurus (cattle) with plateaued light-colors, PMEL mutation affects melanin synthesis and plays a semi-dominant role in color determination (Schmutz & Dreger, 2013). Two mutations in the PMEL gene cause the silvery phenotype of the hourse Equus caballus (Sevane, Sanz & Dunner, 2019) and may cause the plumage of Gallus gallus to be smoky cyan gray or white (Kerje et al., 2004). Deactivation of PMEL in mice caused a large reduction in eumelanin in hair, which plays an important role in maintaining epidermal pigment deposition, but only slightly affected the hair color phenotype of mice (Hellström et al., 2011). In this study, the PMEL gene was enriched in the cellular component, melanosome; and in the two BP, melanosome organization and melanin biosynthetic process. This further indicates that the PMEL gene is a component of melanosomes in the skin of 1-year-old sheep and also participates in the synthesis of melanin. In addition, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) verification found that the expression levels of the PMEL gene were up-regulated in the cyan gray group compared with those in the white group but showed no difference between the W_vs_B and W_vs_R groups. This result is similar to observations in Pashmina goats—black, white and brown (Bhat et al., 2019).

An important group of closely related genes that regulate melanogenesis is the tyrosinase gene family (TYR, tyrosinase-related protein 1, TYRP1, and dopachrome tautomerase DCT). TYR is the key enzyme for regulation of melanogenesis. TYR, TYRP1 and DCT function in stage III of melanosome development, while the melanin corpuscle protein gene, PMEL, is one of the major candidate genes that control coat color (Suzuki, 2013). Dopaquinone is a highly active intermediate cycled through a series of complex redox reactions to finally form melanin (Ito, 2006). When TYR activity is high, eumelanin is synthesized. In contrast, pheomelanin is synthesized when the activity is not high (Gunnarsson et al., 2007; Nadeau, Burke & Mundy, 2007). The missense mutation His214Asn in TYR may induce changes in the chocolate color and melanosome structure in chicken (Ko et al., 2012). Deletion of the 3′ untranslated region of the TYR gene in rabbits resulted in reduced melanin synthesis (Sun et al., 2018).

In our study, the TYR, TYRP1 and DCT genes were enriched in the cellular component, melanosome membrane; TYR and TYRP1 genes were enriched in the BP, melanin biosynthetic process, melanosome organization, and pigmentation; and the DCT gene was enriched in the BP, developmental pigmentation and melanin biosynthetic process from TYR. qRT-PCR verification found that the expression levels of the TYRP1 gene were up-regulated in the three comparison groups, consistent with studies in the black and white mink (Song et al., 2017). The expression levels of the TYR gene were higher in the cyan gray and black groups than in the white group, which was consistent with studies in chicken (Zhang et al., 2015), but showed no significant differences between the light brown and white groups, consistent with the results of RNA-seq. However, the expression of the DCT gene was merely up-regulated in the cyan gray group, consistent with studies in mink and rabbits (Qin et al., 2016; Song et al., 2017).

Solute carrier family 45 member 2 (SLC45A2, also known as MATP) is a transport-related protein, which plays a role in the classification of melanocyte vesicles and in regulating melanin synthesis (Newton et al., 2001; Inagaki et al., 2006). The proteins encoded by this gene are involved in the processing and transportation of TYR, TYRP1 and TYRP2 in cells. Missense mutations can also cause albinism in dogs (Wijesena & Schmutz, 2015). An exon four mutation of SLC45A2 gene may be related to pearl coat color (Sevane, Sanz & Dunner, 2019). In our study, the SLC45A2 gene was enriched in the cellular component, melanosome membrane; and in the two BP, melanin biosynthetic process and developmental pigmentation. The expression levels of the SLC45A2 gene were up-regulated in the cyan gray and black groups, which was consistent with studies in small-tailed Han sheep (Wang et al., 2016) and with the results of our RNA-seq analysis.

Melan-A (MLANA) participates in the production of melanosomes by maintaining the stability of GPR143, which is crucial for the expression, stability, transport and processing of the melanocyte protein PMEL. Together with PMEL, it is regulated by the transcription factor MITF and up-regulation or down-regulation of MITF can regulate endogenous PMEL and MLANA in melanoma cells. Expression of the MLANA gene can also be detected in the skin of patients with vitiligo. In this study, the MLANA gene was merely enriched in the cellular component, melanosome. Its expression level in the four groups of coat color was relatively low, although it was up-regulated in the three comparison groups, consistent with the results of RNA-seq.

The six aforementioned color-related differentially expressed genes showed similar expression trends in the four groups of coat color, even though they have different functions. The PMEL and MLANA genes are components of melanosomes. PMEL is involved in melanosome structure determination and acts as a scaffold in melanosomes by forming a proteolytic fibrillar matrix wherein melanin is deposited. Melanosome formation can be subdivided into different stages of maturity, wherein the PMEL and MLANA genes play a role. Among the four groups of coat color, the expression level of the PMEL gene was higher than that of the MLANA gene, suggesting that the PMEL gene plays a major role in mature melanosomes. Four genes (DCT, TYR, TYRP1 and SLC45A2) were components of the melanosome membrane. Melanosome membrane channels play an important role in melanin synthesis and thus are also involved in melanin synthesis and transportation. The expression level of the four genes (DCT, TYR, TYRP1 and SLC45A2) was the highest in the cyan gray group, suggesting that genes determining the dark color of coats are not expressed more than those determining the light color of coats, consequently, further investigations are required to confirm the mechanism of light color phenotype.

Conclusions

In this study, transcriptome sequencing analysis of the four groups of sheep coat color phenotypes (cyan gray, black, light brown and white) revealed that six differentially expressed genes (DCT, TYR, TYRP1, PMEL, SLC45A2, MLANA) are involved in coat color regulation. These genes were associated with melanocyte differentiation, melanosome transport, developmental pigmentation and melanin biosynthetic process. These six genes, exclusively expressed in the sheep skin with four coat colors, are of particular interest for further studies to elucidate their functional roles in coat color regulation.

Supplemental Information

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the single-base error rate.

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the proportion of a single base.

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the proportion of a single base.

The abscissa represents the sample name and clustering result of the sample and the ordinate represents the clustering result of the differentially expressed genes.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Support Project of China (2015BAD29B06) and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (31260530). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Lidan Yao conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Aodungerile Bao performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Wenjuan Hong performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Chenxi Hou performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Zhenliang Zhang performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, approved the final draft.

Xiaopeng Liang performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, approved the final draft.

Jueken Aniwashi conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Animal Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The Animal Hospital of Xinjiang Agricultural University approved the study (reference number 2018004).

DNA Deposition

The following information was supplied regarding the deposition of DNA sequences:

The sequences are available at NCBI and Figshare. Black group: SRR10143190, SRR10143189, SRR10143186; Cyan gray group: SRR10143185, SRR10143184, SRR10143183; Light brown group: SRR10143182, SRR10143181, SRR10143180; White group: SRR10143188, SRR10143187, SRR10143179.

Lidan, Yao (2019): different coat color sheep skin. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8856698.v1.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data is available as a Supplemental File.

References

- Abdel-Malek et al. (1995).Abdel-Malek Z, Swope VB, Suzuki I, Akcali C, Harriger MD, Boyce ST, Urabe K, Hearing VJ. Mitogenic and melanogenic stimulation of normal human melanocytes by melanotropic peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(5):1789–1793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner et al. (2000).Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat et al. (2019).Bhat B, Singh A, Iqbal Z, Kaushik JK, Rao AR, Ahmad SM, Bhat H, Ayaz A, Sheikh FD, Kalra S, Shanaz S, Mir MS, Agarwal PK, Mohapatra T, Ganai NA. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals the genetic basis of coat color variation in Pashmina goat. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):6361. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42676-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak et al. (2011).Cieslak M, Reissmann M, Hofreiter M, Ludwig A. Colours of domestication. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 2011;86:885–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng et al. (2006).Deng YY, Li JQ, Wu SF, Zhu Y, Chen Y, He F. Integrated nr Database in Protein Annotation System and Its Localization. Computer Engineering. 2006;32(5):71–72. doi: 10.1109/INFOCOM.2006.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finn et al. (2014).Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, Sonnhammer ELL, Tate J, Punta M. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(D1):D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florea, Song & Salzberg (2013).Florea L, Song L, Salzberg SL. Thousands of exon skipping events differentiate among splicing patterns in sixteen human tissues. F1000Research. 2013;2:188. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-188.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratten et al. (2010).Gratten J, Pilkington JG, Brown EA, Beraldi D, Pemberton JM, Slate J. The genetic basis of recessive self-colour pattern in a wild sheep population. Heredity. 2010;104(2):206–214. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson et al. (2007).Gunnarsson U, Hellström AR, Tixier-Boichard M, Minvielle F, Bed’hom B, Ito S, Jensen P, Rattink A, Vereijken A, Andersson L. Mutations in SLC45A2 cause plumage color variation in chicken and Japanese quail. Genetics. 2007;175(2):867–877. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström et al. (2011).Hellström AR, Watt B, Fard SS, Tenza Dèle, Mannström P, Narfström K, Ekesten Börn, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Larsson J, Ulfendahl M, Kullander K, Raposo G, Kerje S, Hallböök F, Marks MS, Andersson L. Inactivation of Pmel alters melanosome shape but has only a subtle effect on visible pigmentation. PLOS Genetics. 2011;7(9):e1002285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki et al. (2006).Inagaki K, Suzuki T, Ito S, Suzuki N, Adachi K, Okuyama T, Nakata Y, Shimizu H, Matsuura H, Oono T, Iwamatsu H, Kono M, Tomita Y. Oculocutaneous albinism type 4: six novel mutations in the membrane-associated transporter protein gene and their phenotypes. Pigment Cell Research. 2006;19(5):451–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito (2006).Ito S. Encapsulation of a reactive core in neuromelanin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(40):14647–14648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606879103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson et al. (2006).Jackson PJ, Douglas NR, Chai B, Binkley J, Sidow A, Barsh GS, Millhauser GL. Structural and molecular evolutionary analysis of agouti and agouti-related proteins. Chemistry & Biology. 2006;13(12):1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerje et al. (2004).Kerje S, Sharma P, Gunnarsson U, Kim H, Bagchi S, Fredriksson R, Schütz K, Jensen P, Von Heijne G, Okimoto R, Andersson L. The Dominant white, Dun and Smoky color variants in chicken are associated with insertion/deletion polymorphisms in the PMEL17 gene. Genetics. 2004;168(3):1507–1518. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko et al. (2012).Ko JM, Yang J-A, Jeong S-Y, Kim H-J. Mutation spectrum of the TYR and SLC45A2 genes in patients with oculocutaneous albinism. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2012;5(4):943–948. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin et al. (2004).Koonin EV, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Krylov DM, Makarova KS, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, Rao BS, Rogozin IB, Smirnov S, Sorokin AV, Sverdlov AV, Vasudevan S, Wolf YI, Yin JJ, Natale DA. A comprehensive evolutionary classification of proteins encoded in complete eukaryotic genomes. Genome Biology. 2004;5(2):R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, Huber & Anders (2014).Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud et al. (2017).Mahmoud AH, Mashaly AM, Rady AM, Al-Anazi KM, Saleh AA. Allelic variation of melanocortin-1 receptor locus in Saudi indigenous sheep exhibiting different color coats. Asian–Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2017;30(2):154–159. doi: 10.5713/ajas.16.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund et al. (1996).Marklund L, Moller MJ, Sandberg K, Andersson L. A missense mutation in the gene for melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MCIR) is associated with the chestnut coat color in horses. Mammalian Genome. 1996;7(12):895–899. doi: 10.1007/s003359900264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, Burke & Mundy (2007).Nadeau NJ, Burke T, Mundy NI. Evolution of an avian pigmentation gene correlates with a measure of sexual selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274(1620):1807–1813. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari-Ghadikolaei et al. (2018).Nazari-Ghadikolaei A, Mehrabani-Yeganeh H, Miarei-Aashtiani SR, Staiger EA, Rashidi A, Huson HJ. Genome-wide association studies identify candidate genes for coat color and mohair traits in the Iranian Markhoz goat. Frontiers in Genetics. 2018;9:267. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton et al. (2001).Newton JM, Cohen-Barak O, Hagiwara N, Gardner JM, Davisson MT, King RA, Brilliant MH. Mutations in the human orthologue of the mouse underwhite gene (uw) underlie a new form of oculocutaneous albinism, OCA4. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;69(5):981–988. doi: 10.1086/324340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris & Whan (2008).Norris BJ, Whan VA. A gene duplication affecting expression of the ovine ASIP gene is responsible for white and black sheep. Genome Research. 2008;18(8):1282–1293. doi: 10.1101/gr.072090.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea et al. (2015).Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang T-C, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature Biotechnology. 2015;33(3):290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin et al. (2016).Qin LZ, Wang WZ, Shi LJ, Wan XY, Yan XR, Weng QQ, Wu XS. Transcriptome expression profiling of fur color formation in domestic rabbits using Solexa sequencing. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2016;15(2):8409–8413. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15027413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochus et al. (2019).Rochus CM, Westberg Sunesson K, Jonas E, Mikko S, Johansson AM. Mutations in ASIP and MC1R: dominant black and recessive black alleles segregate in native Swedish sheep populations. Animal Genetics. 2019;50(6):712–717. doi: 10.1111/age.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz & Dreger (2013).Schmutz SM, Dreger DL. Interaction of MC1R and PMEL alleles on solid coat colors in Highland cattle. Animal Genetics. 2013;44(1):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2012.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevane, Sanz & Dunner (2019).Sevane N, Sanz CR, Dunner S. Explicit evidence for a missense mutation in exon 4 of SLC45A2 gene causing the pearl coat dilution in horses. Animal Genetics. 2019;50(3):275–278. doi: 10.1111/age.12784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon et al. (2009).Simon JD, Peles D, Wakamatsu K, Ito S. Current challenges in understanding melanogenesis: bridging chemistry, biological control, morphology, and function. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2009;22(5):563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al. (2017).Song X, Xu C, Liu Z, Yue Z, Liu L, Yang T, Cong B, Yang F. Comparative transcriptome analysis of mink (Neovison vison) skin reveals the key genes involved in the melanogenesis of black and white coat colour. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):12461. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2018).Sun W, Shen Y, Shan S, Han L, Li Y, Zhou Z, Zhong Z, Chen J. Identification of TYR mutations in patients with oculocutaneous albinism. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2018;17(6):8409–8413. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki (2013).Suzuki H. Evolutionary and phylogeographic views on Mc1r and Asip variation in mammals. Genes & Genetic Systems. 2013;88(3):155–164. doi: 10.1266/ggs.88.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki et al. (1996).Suzuki I, Cone RD, Im S, Nordlund J, Abdel-Malek ZA. Binding of melanotropic hormones to the melanocortin receptor MC1R on human melanocytes stimulates proliferation and melanogenesis. Endocrinology. 1996;137(5):1627–1633. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov et al. (2000).Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Våge et al. (1999).Våge DI, Klungland H, Lu D, Cone RD. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of dominant black coat color in sheep. Mammalian Genome. 1999;10(1):39–43. doi: 10.1007/s003359900939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher (2017).Visscher MO. Skin color and pigmentation in ethnic skin. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2017;25(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2016).Wang H, Xue L, Li Y, Zhao B, Chen T, Liu Y, Chang L, Wang J. Distribution and expression of SLC45A2 in the skin of sheep with different coat colors. Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 2016;54(3):143–150. doi: 10.5603/FHC.a2016.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesena & Schmutz (2015).Wijesena HR, Schmutz SM. A missense mutation in SLC45A2 is associated with Albinism in several small long haired dog breeds. Journal of Heredity. 2015;106(3):285–288. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esv008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2013).Yang G-L, Fu D-L, Lang X, Wang Y-T, Cheng S-R, Fang S-L, Luo Y-Z. Mutations in MC1R gene determine black coat color phenotype in Chinese sheep. Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013(5):675382. doi: 10.1155/2013/675382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue et al. (2015).Yue X, Nie Q, Xiao G, Liu B. Transcriptome analysis of shell color-related genes in the clam Meretrix meretrix. Marine Biotechnology. 2015;17(3):364–374. doi: 10.1007/s10126-015-9625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2015).Zhang J, Liu F, Cao J, Liu X. Skin transcriptome profiles associated with skin color in chickens. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0127301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the single-base error rate.

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the proportion of a single base.

Horizontal coordinate is the base location of reads and vertical coordinate is the proportion of a single base.

The abscissa represents the sample name and clustering result of the sample and the ordinate represents the clustering result of the differentially expressed genes.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data is available as a Supplemental File.