Abstract

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) comprise 10% of the genome, with many of these transcriptionally silenced post early embryogenesis. Several stimuli, including exogenous virus infection and cellular transformation can reactivate ERV expression via a poorly understood mechanism. We identified Interferon Regulatory Factor 1 (IRF-1), a tumor suppressor and an antiviral host factor, as a suppressor of ERV expression. IRF-1 decreased expression of a specific mouse ERV in vitro and in vivo. IRF-3, but not IRF-7, also decreased expression of distinct ERV families, suggesting that suppression of ERVs is a relevant biological function of the IRF family. Given the emerging appreciation of the physiological relevance of ERV expression in cancer, IRF-1-mediated suppression of specific ERVs may contribute to the overall tumor suppressor activity of this host factor.

Keywords: endogenous retroviruses, Interferon Regulatory Factor, cancer

Introduction

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are the proviral remains of ancient exogenous retroviral infections of mammalian ancestors’ germline. ERV sequences represent 8% and 10% of the human and mouse genomes, respectively (Harris et al., 2001; Waterston et al., 2002) and are classically composed of gag, pro, pol, and env genes, which are flanked by long terminal repeats (LTRs). ERVs are generally subdivided into three classes (I, II, III) based on the class of exogenous retroviruses they most closely resemble (reviewed in (Kurth and Bannert, 2010; Stocking and Kozak, 2008)). While ERVs are abundant in mammalian genomes, very few have maintained the ability to form infectious viral particles, as the overwhelming majority have accumulated mutations and deletions over evolution. Additionally, host cells have adapted to suppress ERV transcription. This suppression occurs globally during early embryogenesis, via several mechanisms, such as histone modifications and DNA methylation (Karimi et al., 2011; Rowe et al., 2013).

Although transcription of many ERVs is suppressed beyond early embryogenesis, it has recently become clear that expression of certain ERVs can be reactivated in response to a number of stresses, such as exogenous infection or transformation. Specifically, infection with human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) activates transcription of several human ERVs in vitro (Assinger et al., 2013). In vivo, high HCMV load in kidney transplant patients correlates with higher ERV gene expression (Bergallo et al., 2015) and metagenome analysis of colon tissues from inflammatory bowel disease patients indicates a positive correlation between abundance of herpesvirus sequences and ERV transcripts (Wang et al., 2015). Importantly, the mechanism responsible for reactivation of ERVs following exogenous virus infection remains poorly understood.

ERVs are also reactivated in diverse cancer types, including leukemia, B cell follicular lymphoma, melanoma, and breast cancer (Attig et al., 2017; Bergallo et al., 2017; Buscher et al., 2005; Wang-Johanning et al., 2008). The limited studies that explored the physiological relevance of ERVs in cancer cells showed that genetic targeting of specific transcriptionally active ERVs led to decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, and/or increased immune-mediated elimination of tumors in xenograft models (Mangeney et al., 2005; Oricchio et al., 2007). Conversely, forced expression of select ERV genes induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition in non-tumorigenic cell lines (Lemaitre et al., 2017). While transcriptionally active ERVs may contribute to transformation, including via insertional mutagenesis, the molecular mechanisms responsible for increased expression of these elements in cancer remain mostly unknown or are poorly understood.

Interferon Regulatory Factor-1 (IRF-1) is a transcription factor that attenuates replication of multiple RNA and DNA viruses (Brien et al., 2011; Mboko et al., 2014; Pflugheber et al., 2002; Schoggins et al., 2014; Schoggins et al., 2011) and is also a tumor suppressor (Connett et al., 2005; Kuroboshi et al., 2003; Nozawa et al., 1999; Nozawa et al., 1998; Tanaka et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2007). In spite of its given name (Miyamoto et al., 1988), IRF-1 is not involved in the induction of type I interferon (IFN) responses following viral infections (Brien et al., 2011; Kimura et al., 1994; Maloney et al., 2012; Mboko et al., 2014; Mboko et al., 2016) and thus, the mechanism behind the broad antiviral activity exerted by this transcription factor remains unclear. While some of the molecular mechanisms responsible for IRF-1 tumor suppressor functions have been identified, the extent to which the antiviral and tumor suppressor mechanisms overlap is not known.

In this study we identify a novel role of IRF-1 as a suppressor of a specific mouse ERV. The ability of IRF-1 to suppress ERV expression was evident in several primary mouse cell types cultured in vitro and in animal organs ex vivo. This capacity to attenuate ERVs was found to be shared by related transcription factor IRF-3, but not IRF-7, suggesting that suppression of diverse ERVs may be a relevant biological function of the IRF family.

Results.

IRF-1 suppresses endogenous reverse transcriptase (RT) activity.

Many of the recently integrated ERV families retain an intact RT gene. Due to the genetic diversity of the ERV landscape, a sensitive, real time PCR-based, RT activity assay was adapted from a previous publication (Pyra et al., 1994) to comprehensively detect expression of retroelements that encode an enzymatically active RT gene. In this assay, a commercially available RNA from MS2 phage is used as a template to preclude the presence of the DNA template version in mammalian cell lysates. The level of the detection of this assay is defined by both the linear limits of the standard curve of RT activity generated in each assay as well as the signal produced by real time PCR of the phage RNA template in the absence of exogenous or endogenous RT, with a typical limit of detection of 10−8 units of RT/microgram of protein.

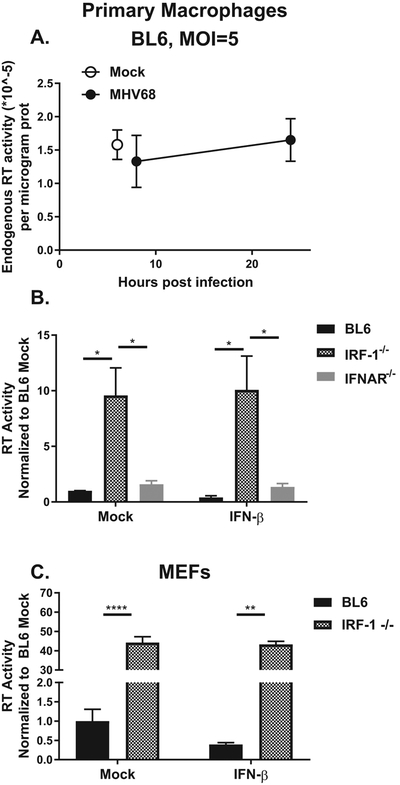

Given previous reports that demonstrated increased expression of ERVs following HCMV infection (Assinger et al., 2013), we wanted to determine if an infection with a cancer-associated gammaherpesvirus increases endogenous RT activity indicating increased expression of retroelements. Gammaherpesviruses, such as mouse gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68), are ubiquitous exogenous pathogens that establish life-long infection and are associated with a number of malignancies (Cesarman, 2014; Tarakanova et al., 2008; Tarakanova et al., 2005). Interestingly, MHV68 infection of primary macrophages failed to alter low levels of endogenous RT activity at both high (Fig. 1A) and low multiplicity of infection (Darrah et al., 2017), in contrast to published HCMV studies.

Figure 1. IRF-1 suppresses endogenous reverse transcriptase (RT) activity.

(A, B) Primary macrophages were derived from bone marrow of mice of indicated genotypes. A. Macrophages were mock-treated or infected with MHV68. Reverse transcriptase activity was measured in cell lysates isolated at indicated time post infection. B. Macrophages were mock treated or incubated in the presence of recombinant IFNβ for 8 hours and reverse transcriptase activity measured in cell lysates. C. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts of indicated genotypes were mock-treated or treated with IFNβ as in B. Reverse transcriptase activity was measured in cell lysates collected at 8 hours post treatment. Data were pooled from 2-4 independent experiments. In this and other figures the mean is shown with error bars representing standard error of mean (SEM). *p<0.05; **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. Only those differences that have reached statistical significance are defined as such in all figures.

Due to the profoundly antiviral nature of primary macrophages, we next tested the hypothesis that type I interferon (IFN) signaling or expression of IRF-1, a broadly antiviral host factor, could suppress expression of enzymatically active RT encoded by endogenous retroelements. Macrophages isolated from mice genetically deficient in type I IFN receptor (IFNAR−/−) showed a slight (~ two-fold, no statistical significance) increase in the endogenous RT activity (Fig. 1B). Accordingly, treatment of naïve macrophages with recombinant IFN-β failed to significantly alter endogenous RT activity. In contrast, macrophages derived from IRF-1−/− mice displayed a substantial (~10-fold) increase in endogenous RT activity, an increase that was not further modulated by treatment with IFN-β (Fig. 1B).

IRF-1 can manifest its antiviral activity in a cell type and organ-dependent manner, as evidenced by enhanced replication of West Nile virus in IRF-1−/− macrophages, but not in IRF-1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and enhanced tropism of West Nile virus for the central nervous system in the absence of IRF-1 (Brien et al., 2011). In order to determine whether IRF-1-dependent suppression of endogenous RT activity was cell type specific, RT activity was measured in MEFs. Endogenous RT activity was substantially elevated in IRF-1−/− MEFs and this increase was not affected by IFN-β treatment (Fig. 1C). Of note, IFNβ treatment of wild type, but not IRF-1−/− MEFs resulted in ~2-fold decrease in RT activity that was not statistically significant. In summary, exogenous gammaherpesvirus infection failed to alter endogenous RT activity. In contrast, IRF-1 deficiency of the host resulted in increased endogenous RT activity in primary mouse macrophages and fibroblasts.

IRF-1 selectively suppresses Emv2 expression.

Several families of ERVs are known to encode an enzymatically active RT and reactivation of such ERVs could be responsible for increased endogenous RT activity observed in IRF-1 deficient cells. In order to identify ERV families that may be contributing to increased endogenous RT activity, pan-specific consensus primers were utilized (Table 1). These primers were directed towards three ERV families: the Class I Murine Leukemia Virus (MLV) family, the Class II Mus musculus ERVs that use tRNALys type-10C (mMERVK-10C), and the Class III Intracisternal-A Particle (IAP) family. All three families are present in multiple copies within the C57BL/6J (BL6) genome, have the potential to be transpositionally active, and contain a functional RT gene (Dewannieux et al., 2004; Fasching et al., 2015; Jern et al., 2005; Kozak, 2015). For the MLV family, three separate consensus primer sets were utilized (Emv, xMLV, and pMLV) in order to detect three different variants (ecotropic, xenotropic, and polytropic) present within the genome. Of note, in contrast to xMLV and pMLV, Emv is present as a unique locus in the C57BL/6J genome (Emv2) (Jenkins et al., 1982) and encodes a mutated RT enzyme with a significantly attenuated RT activity (King et al., 1988).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence | Citation | Gene detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT1 | CATAGGTCAAACCTCCTAGGAATG | (Pyra et al., 1994) | MS2 phage |

| RT2 | TCCTGCTCAACTTCCTGTCGAG | Pyra et al., 1994 | MS2 phage |

| Emv (Emv2) For | TTCTGCTCCTCTTCTGCCCT | Collins et al., 2015 | gag |

| Emv (Emv2) Rev | GAGGACCCTGGGCAAGAAAC | Collins et al., 2015 | gag |

| pMLV For | CCGCCAGGTCCTCAATATAG | Yoshinobu et al., 2009 | env (gp70) |

| pMLV Rev | AGAAGGTGGGGCAGTCT | Yoshinobu et al., 2009 | env (gp70) |

| xMLV For | TCTATGGTACCTGGGGCTC | Yoshinobu et al., 2009 | env (gp70) |

| xMLV Rev | GGCAGAGGTATGGTTGGAGTAG | Yoshinobu et al., 2009 | env (gp70) |

| Xmv43 For | GGGCAGCAGTGACGACT | This study | pol |

| Xmv43 Rev | TTCGGCACTGTCTCCTTTCT | This study | pol |

| Xmv45 For | GGGATGGCGACAGAGAAGAG | This study | gag |

| Xmv45 Rev | GTCAGCAGAGTCCCCAACAA | This study | gag |

| mMERV-K For | CAAATAGCCCTACCATATGTCAG | Rowe et al., 2013 | gag |

| mMERV-K Rev | GTATACTTTCTTCTTCAGGTCCAC | Rowe et al., 2013 | gag |

| IAP For | AAGCAGCAATCACCCACTTTGG | Collins et al., 2015 | gag |

| IAP Rev | CAATCATTAGATGCGGCTGCCAAG | Collins et al., 2015 | gag |

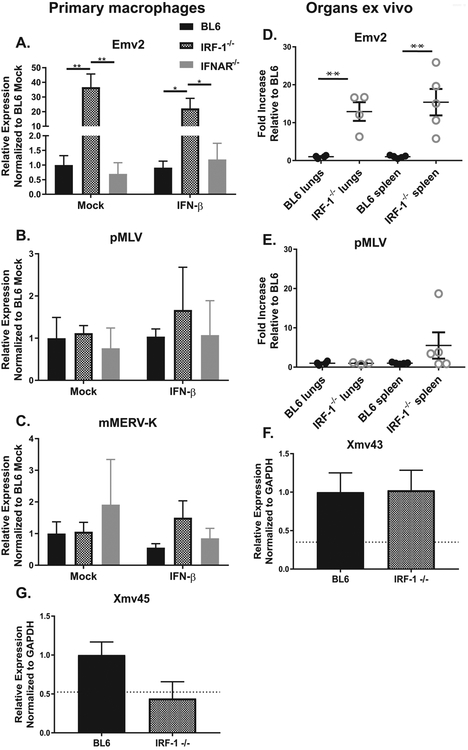

Intriguingly, expression of Emv2 was significantly increased in IRF-1−/− macrophages as compared to BL6 controls (Fig. 2A). Similar to the RT activity, this increase was not significantly altered by IFNβ treatment, nor was Emv2 expression increased in IFNAR−/− macrophages, regardless of experimental conditions (Fig. 2A). In contrast to that observed for Emv2, no other ERV family that was analyzed showed differential expression in IRF-1−/− macrophages (Fig. 2B, C; data not shown for xMLV and IAP). Similarly, IFN-β treatment did not affect low levels of expression of these ERVs, in either wild type or IRF-1−/− conditions. (Fig. 2B, C).

Figure 2. IRF-1 selectively suppresses Emv2 expression.

(A-C, F, G). Primary macrophages of indicated genotypes were mock-treated or treated with IFNβ for 8 hours. Levels of indicated transcripts were measured by RT-qPCR. Data were pooled from at least two independent experiments. Dotted line in F and G indicates level of detection (no RT controls). (D, E). RNA was isolated from lungs and spleens harvested from naïve animals of indicated genotypes. Levels of indicated transcripts were measured by RT-qPCR. Each symbol represents an individual animal.

In order to determine if IRF-1 similarly regulates expression of select ERV families in vivo, expression of ERVs was measured in lungs and spleens harvested from naïve BL6 or IRF-1−/− mice. Similar to that observed in primary macrophages, expression of Emv2 was elevated in lungs and spleens of IRF-1−/− mice as compared to BL6 controls (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, in contrast to that observed in primary macrophages, expression of pMLV appeared to be elevated in IRF-1−/− spleens, albeit the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.11, Fig. 2E). Finally, expression of mMERVK-10C and IAP remained at the level of no RT control in all tested organs (data not shown). In summary, IRF-1 selectively suppressed expression of Emv2 in primary macrophage cultures and in lungs and spleens in vivo.

Direct IRF-1 association with ERV sequences is not necessary to repress ERV expression

IRF-1 regulates gene expression via direct interaction of its DNA binding domain with the IFN stimulated response element that is similar for all members of the IRF family (Fujii et al., 1999). Association of IRF-1 with other cellular transcriptional factors determines the specificity of genes that are directly regulated by IRF-1. Having observed increased Emv2 expression in the absence of IRF-1, it was possible that IRF-1 suppressed Emv2 via direct binding. While ecotropic MLV proviruses can be present in multiple copies in other mouse strains, only a single copy (Emv2) is present on chromosome 8 of C57BL/6J mice (Jenkins et al., 1982). Since this provirus is not repetitive in the BL6 genome, it is identifiable by next generation sequencing data, even if repetitive sequences are removed prior to analyses. To determine if IRF-1 directly bound to the Emv2 genetic locus, data were mined from a published IRF-1 ChIP seq study that utilized primary BL6 macrophages (Langlais et al., 2016). Interestingly, IRF-1 was not associated with the Emv2 provirus, indicating that another cellular protein that is expressed in an IRF-1-dependent manner is responsible for the silencing of Emv2 expression.

Using the same dataset (Langlais et al., 2016) in combination with the Endogenous Retroviral Element (ERE) database (Kao et al., 2012) we identified two additional related ERVs, commonly known as Xmv43 (Bxv1) and Xmv45 (XmvIV) (see genomic coordinates in Table 2) with the former ERV genome bound by IRF-1, and the latter not. Interestingly, expression of either Xmv43 or Xmv45 was not increased in IRF-1−/− macrophages (Fig. 2F, G), supporting the conclusion that direct binding of IRF-1 to ERV sequences is neither necessary nor sufficient to suppress ERV expression.

Table 2.

Genomic coordinates (NCBI37/mm9) of specific mouse ERV loci analyzed in this study.

| ERV | chr | start | end | coding direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xmv43 | chr1 | 172871652 | 172880308 | + |

| Xmv45 | chr5 | 23206397 | 23215063 | − |

| Emv2 | chr8 | 125949704 | 125958431 | − |

IRF-3 suppresses expression of several ERV families.

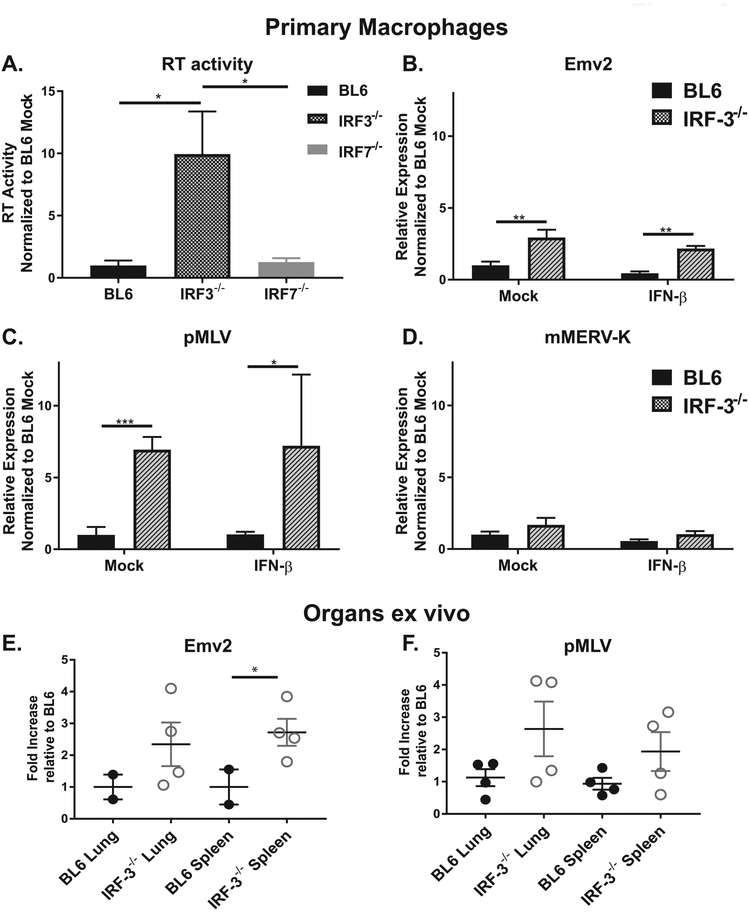

IRF-1 is the founding member of the IRF family, which comprises 9 members in humans and mice (reviewed in (Tamura et al., 2008)). While all IRF transcription factors have a similar DNA binding domain, each regulates a distinct group of genes and biological processes, a regulation that is frequently modified in a cell type-specific manner. IRF-3 and IRF-7 are most relevant members of the family with respect to viral infection: both of these transcription factors (in contrast to IRF-1) are important in induction of type I IFN expression in infected cells (Sato et al., 2000). Importantly, in addition to indirect regulation of cellular gene expression via induction of type I IFN, both IRF-3 and IRF-7 can directly regulate specific cellular genes (Barnes et al., 2004; Freaney et al., 2013). In order to determine the extent to which IRF-3 or IRF-7 regulate ERV expression, endogenous RT activity was measured in IRF-3−/− and IRF-7−/− primary macrophages. IRF-7 deficiency had no effect on the endogenous RT activity (Fig. 3A). In contrast, IRF-3−/− macrophages displayed a significant increase in RT activity (Fig. 3A), suggesting that IRF-3 may suppress ERV expression.

Figure 3. IRF-3 suppresses expression of several ERV families.

A. Endogenous RT activity was measured in cell lysates harvested from bone marrow derived macrophages of indicated genotypes. (B-D). Macrophages of indicated genotypes were treated as in Fig. 2. Levels of indicated transcripts were measured by RT-qPCR. Data were pooled from at least two independent experiments. (E, F). RNA was isolated from lungs and spleens harvested from naïve animals of indicated genotypes. Levels of indicated transcripts were measured by RT-qPCR. Each symbol represents an individual animal.

To test this hypothesis, expression of specific ERV families was assessed. Unlike IRF-1−/− macrophages, IRF-3−/− macrophages displayed only a modest increase in the expression of Emv2 (~3-fold, Fig. 3B). In contrast, expression of pMLV family of ERVs was robustly increased in IRF-3−/− macrophages (Fig. 3C, ~ 7 fold). Similar to that observed for IRF-1, IRF-3 deficiency had no effect on the expression of mMERV-K ERV family (Fig. 3D). Further, type I IFN treatment had very little effect on the expression of ERVs in IRF-3−/− macrophages (Fig. 3B-D). In summary, IRF-3 deficiency led to selective expression of pMLV and, to a lesser extent, Emv2 in primary macrophages.

To determine the extent to which IRF-3 regulates transcription of select ERVs in vivo, transcription of Emv2 and pMLV was analyzed in organs of IRF-3−/− mice. Expression of Emv2 remained elevated in IRF-3−/− as compared to BL6 spleens (Fig. 3E). Expression of pMLV in lungs and spleens of IRF-3−/− mice was more heterogenous, with only half of the IRF-3−/− animals displaying increased expression (Fig. 3F). Thus, IRF-3 deficiency led to a modest elevation in expression of Emv2 and pMLV in lungs and spleens and this phenotype was not always fully penetrant in the analyzed animal cohorts. In summary, repression of select ERV expression was not a unique function of IRF-1, but was, instead, shared with at least one other member of IRF family, IRF-3.

Discussion

In this study we identified IRF-1 as a novel suppressor of Emv2 expression. This suppression was evident in diverse somatic cells and organs of adult mice, suggesting that IRF-1 is an important host factor that controls expression of Emv2 post embryogenesis. Interestingly, IRF-3, a related IRF family member, also suppressed expression of select type I family ERVs, including Emv2, suggesting that attenuation of ERV expression may be a biologically relevant function of the IRF family members.

Mechanism of ERV suppression.

While our studies identify a novel role of IRF-1 in suppression of Emv2, other immune mechanisms were previously shown to suppress ERVs past early embryogenesis. One of such immune mechanisms is mediated via toll like receptor 7 (TLR7) (Yu et al., 2012). TLR7−/− mice lack class switched ERV neutralizing antibodies, a deficiency that was proposed to be responsible for the ERV viremia (Yu et al., 2012). This was further supported by the Kassiotis group that demonstrated increased Emv2 expression in several mouse models of B cell deficiency and defined the requirement for Myd88, a critical adaptor downstream of TLR7, for the control of Emv2 expression in vivo (Young et al., 2012). In contrast, IRF-1 deficiency does not interfere with efficient generation of class-switched neutralizing antiviral antibodies against exogenous DNA and RNA viruses (Brien et al., 2011; Mboko et al., 2015), making this an unlikely mechanism by which IRF-1 suppresses Emv2 expression. Intriguingly, increased Emv2 expression in TLR7−/− and B cell deficient mice was ablated when mice were given acidified water, suggesting microbiome effects on the observed phenomenon (Young et al., 2012). In contrast, despite receiving acidified water in our animal facility, IRF-1−/− mice maintained increased Emv2 expression, suggesting that microbiome does not affect IRF-1-mediated Emv2 suppression.

We found that type I IFN was neither sufficient nor necessary to significantly alter expression of examined ERVs, including in the absence of IRF-1. This is consistent with the reports demonstrating that IRF-1 is not involved in the induction of type I IFN responses following viral infections (Brien et al., 2011; Kimura et al., 1994; Maloney et al., 2012; Mboko et al., 2014; Mboko et al., 2016) While IRF-1 expression is stimulated by both type I and type II IFN, IRF-1 is constitutively expressed in unstimulated MEFs and primary macrophages. This baseline IRF-1 expression is sufficient to attenuate exogenous gammaherpesvirus replication even in the absence of type I IFN signaling (Mboko et al., 2016), supporting the hypothesis that IRF-1-mediated suppression of Emv2 is IFN-independent. Interestingly, we discovered that IRF-3, a related IRF family member with constitutive expression, also suppresses expression of pMLV family, and to a much lesser extent Emv2 (Fig. 3). Unlike IRF-1, IRF-3 is important for induction of type I IFN expression in response to viral infection. However, IRF-3 can also directly regulate expression of target genes independent of IFN, a potential mechanism by which ERV suppression is mediated.

Using published ChIP-seq dataset (Langlais et al., 2016) we ruled out direct association of IRF-1 with the Emv2 locus, indicating that another transcription factor that is expressed in an IRF-1-dependent manner is responsible for the observed phenotype. Zfp809 was identified by the Goff group as a zinc finger protein that suppresses Emv2 expression in embryonic stem cells (Wolf and Goff, 2009). However, Zfp809 protein is rapidly and constitutively degraded in somatic cells (Wang and Goff, 2017). Further, Zfp809 was not differentially expressed in IRF-1−/− macrophages (Langlais et al., 2016), making it an unlikely contributor to the observed Emv2 suppression. Future studies are needed to determine the identity of the IRF-1-dependent cellular factor that mediates suppression of Emv2.

Emv2 encodes a mutated RT that only maintains a fraction of the original enzymatic activity (King et al., 1988), which may explain differences we observed between the endogenous RT activity and Emv2 expression in IRF-1−/− cells (~10-fold vs. ~40-fold, Fig. 1B, 2A). It is possible that derepressed expression of other retroelements that were not detected by the primers used in this study contributes to the endogenous RT activity in IRF-1−/− cells. Another important future direction is to determine whether expression of Emv2 in IRF-1−/− mice is accompanied by its recombination with other ERVs, leading to a change in the tropism of the resulting recombinant virus (via envelope switch), an acquisition of a fully functional RT gene, or other genetic changes. We detected a similar increase in the expression of Emv2 env and gag genes in IRF-1−/− macrophages (data not shown), making the first possibility unlikely; however, other recombination events cannot be ruled out.

Implications of IRF-1-mediated suppression of endogenous retroelements.

IRF-1 is a well-established tumor suppressor; however, the mechanisms responsible for tumor suppression are incompletely understood. IRF-1 expression mediates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of malignant cells (Armstrong et al., 2012; Bouker et al., 2005; Kroger et al., 2007) and IRF-1 cooperates with p53 downstream of genotoxic stress (Tanaka et al., 1996). However, IRF-1 deficiency synergizes with p53 deficiency to exacerbate tumorigenesis in mouse models (Nozawa et al., 1999), suggesting that some of tumor suppressor functions of IRF-1 are p53 independent.

Increased expression of Emv2 in antibody-deficient mice led to the generation of recombinant infectious virus and subsequent lymphomagenesis (Young et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012), with the evidence of insertional mutagenesis in lymphomas. In contrast, while expression of ERVs is induced in a number of human cancers, the physiological relevance of such induction is mostly unclear. The handful of studies that explored the physiological relevance of ERVs in transformed cells showed that increased expression supported proliferation, cell viability and immune evasion of tumors in xenograft models (Mangeney et al., 2005; Oricchio et al., 2007). Our findings offer an intriguing possibility that IRF-1-mediated repression of specific ERVs may contribute to its tumor suppressor functions. Intriguingly, mice with single IRF-1 deficiency have not been reported to spontaneously develop cancer. However, increased ERV expression in TLR7−/− mice also did not lead to tumorigenesis and additional deficiencies of TLR3 and TLR9 were required for spontaneous generation of T cell lymphomas with a very long latency time (over 12 months) (Yu et al., 2012). Thus, it is possible that aging of IRF-1−/− mice or introduction of additional genetic modifications (such as IRF-3 deficiency) would unveil spontaneous tumorigenesis.

Materials and Methods.

Animals.

C57BL/6J (BL6) and IRF-1−/− mice (Matsuyama et al., 1993) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). IFNAR1−/− mice on the BL6 background were a gift from Dr. Mitchell Grayson (Grayson et al., 2007). IRF-3−/− and IRF-7−/− mice were a gift from Dr. Michael Diamond (Honda et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2000). All mice utilized in this study are on the C57BL/6J background. Organs were harvested from naïve mice between 8 and 12 weeks of age. Mice were housed and bred in a specific-pathogen-free barrier facility in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines. All experimental manipulations of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Primary Macrophage Derivation and Treatment.

Primary bone marrow derived macrophages were harvested from mice between 3 and 10 weeks of age, as previously described (Tarakanova et al., 2007). Macrophages were infected with MHV68 (WUMS) at indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 1 hour to allow for adsorption, and washed three times with PBS prior to media replenishment. Alternatively, recombinant interferon-β (IFN-β) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) was added at a concentration of 10U/mL.

Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast (MEF) Derivation.

MEFs were derived on day 12-14 of pregnancy. Embryos were separated from placenta, fetal tissue homogenate was seeded in T175 flask and cultured in DMEM (Corning, Corning, NY) containing 10% Fetal Calf Serum (Biowest, Riverside, MO), and supplemented with nonessential amino acids, glutamine, and pen/strep (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). MEFs were passaged twice before experimental use.

Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Activity Assay.

Reverse transcriptase (RT) activity assay was adapted from published study (Pyra et al., 1994). Briefly, cells were harvested in lysis buffer containing 0.5% triton X-100, Tris-Cl (pH8.3), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Samples were freeze thawed (−80 °C) and cleared by centrifugation, to ensure removal of cellular debris. 5μL of the precleared cell lysate was added to a master mix containing MS2 phage RNA (US Biological Life Sciences, Salem, MA), which acted as an RT template. The master mix also contained RT1 primer, specific to the phage RNA sequence (Table 1), RNAseOUT™ (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), and salmon sperm DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to attenuate endogenous DNAse activity of the cell lysates. Prior to being added to the master mix, the MS2 phage RNA and RT1 primer were pre-mixed separately and heated at 60°C for 2 minutes to denature RNA secondary structures and allow for primer binding. Following the addition of the precleared lysate to the master mix, reverse transcription was allowed to proceed for 45 minutes at 42°C. To control for residual endogenous endonuclease activity in individual cell lysates that could target the RT-generated cDNA, each cell lysate was run in duplicate, with one of the duplicate reactions spiked with excess of recombinant M-MLV reverse transcriptase (20mU/sample, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). After the reverse transcription reaction, samples and standards were analyzed by real time PCR using RT1 and RT2 primers (Table 1). For each run a standard curve from 10−3 to 10−7 units of RT was created using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), providing a typical limit of detection of 10−8 units of RT/microgram of protein. RT activity was normalized to protein concentration in each sample. Individual endogenous RT activity was further corrected based on the level of inhibition of spiked RT activity observed for each sample. Additional controls performed in each run included real time PCR of phage RNA template (in the presence of RT1 and RT2, but in the absence of cell lysate or recombinant RT) to evaluate the level of DNA contamination of MS2 RNA that was considered when defining the sensitivity of the RT assay.

RT-qPCR Analysis.

Total RNA was harvested, reverse transcribed, and analyzed by RT-qPCR as previously described (Mboko et al., 2014). Organs were harvested into 1ml of Trizol (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) containing 1 mm zirconia beads (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK) and disrupted by Magnalyzer (Roche) prior to RNA isolation. Random hexamer primers (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) were used during the RT step. cDNA was assessed in triplicate, along with corresponding minus reverse transcriptase reactions, by real-time PCR using a CFX Connect system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Analysis was performed using previously published primers for MMERVK-10C (Fasching et al., 2015), pMLV (Yoshinobu et al., 2009), and Emv (Collins et al., 2015); primer sequences are provided in Table 1. Primers used in this study were validated for sensitivity and specificity using bioinformatic and wet lab approaches; the slope and linear range was established for each primer pair, and all primers were utilized within their linear range.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All p values were calculated using Student’s t-test. Student’s t-test was preformed between each experimental condition for data pooled from multiple experiments, with only the significant p values represented in each figure.

Acknowledgements.

This study was supported by CA183593, CA203923 (V.L.T.), CA204231 (S.R).

References.

- Armstrong MJ, Stang MT, Liu Y, Gao J, Ren B, Zuckerbraun BS, Mahidhara RS, Xing Q, Pizzoferrato E, Yim JH, 2012. Interferon Regulatory Factor 1 (IRF-1) induces p21(WAF1/CIP1) dependent cell cycle arrest and p21(WAF1/CIP1) independent modulation of survivin in cancer cells. Cancer Lett 319, 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assinger A, Yaiw KC, Gottesdorfer I, Leib-Mosch C, Soderberg-Naucler C, 2013. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) induces human endogenous retrovirus (HERV) transcription. Retrovirology 10, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attig J, Young GR, Stoye JP, Kassiotis G, 2017. Physiological and Pathological Transcriptional Activation of Endogenous Retroelements Assessed by RNA-Sequencing of B Lymphocytes. Front Microbiol 8, 2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes BJ, Richards J, Mancl M, Hanash S, Beretta L, Pitha PM, 2004. Global and distinct targets of IRF-5 and IRF-7 during innate response to viral infection. J Biol Chem 279, 45194–45207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergallo M, Galliano I, Montanari P, Gambarino S, Mareschi K, Ferro F, Fagioli F, Tovo PA, Ravanini P, 2015. CMV induces HERV-K and HERV-W expression in kidney transplant recipients. J. Clin. Virol 68, 28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergallo M, Montanari P, Mareschi K, Merlino C, Berger M, Bini I, Dapra V, Galliano I, Fagioli F, 2017. Expression of the pol gene of human endogenous retroviruses HERV-K and -W in leukemia patients. Arch Virol 162, 3639–3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouker KB, Skaar TC, Riggins RB, Harburger DS, Fernandez DR, Zwart A, Wang A, Clarke R, 2005. Interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) exhibits tumor suppressor activities in breast cancer associated with caspase activation and induction of apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 26, 1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien JD, Daffis S, Lazear HM, Cho H, Suthar MS, Gale M Jr., Diamond MS, 2011. Interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) shapes both innate and CD8(+) T cell immune responses against West Nile virus infection. PLoS. Pathog 7, e1002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher K, Trefzer U, Hofmann M, Sterry W, Kurth R, Denner J, 2005. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus K in melanomas and melanoma cell lines. Cancer Res 65, 4172–4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, 2014. Gammaherpesviruses and lymphoproliferative disorders. Annu. Rev. Pathol 9, 349–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PL, Kyle KE, Egawa T, Shinkai Y, Oltz EM, 2015. The histone methyltransferase SETDB1 represses endogenous and exogenous retroviruses in B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 8367–8372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connett JM, Badri L, Giordano TJ, Connett WC, Doherty GM, 2005. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 expression in breast cancer tissue microarrays. J. Interferon Cytokine Res 25, 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrah EJ, Stoltz KP, Ledwith M, Tarakanova VL, 2017. ATM supports gammaherpesvirus replication by attenuating type I interferon pathway. Virology 510, 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewannieux M, Dupressoir A, Harper F, Pierron G, Heidmann T, 2004. Identification of autonomous IAP LTR retrotransposons mobile in mammalian cells. Nat Genet 36, 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasching L, Kapopoulou A, Sachdeva R, Petri R, Jonsson ME, Manne C, Turelli P, Jern P, Cammas F, Trono D, Jakobsson J, 2015. TRIM28 represses transcription of endogenous retroviruses in neural progenitor cells. Cell Rep. 10, 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freaney JE, Kim R, Mandhana R, Horvath CM, 2013. Extensive cooperation of immune master regulators IRF3 and NFkappaB in RNA Pol II recruitment and pause release in human innate antiviral transcription. Cell Rep 4, 959–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Shimizu T, Kusumoto M, Kyogoku Y, Taniguchi T, Hakoshima T, 1999. Crystal structure of an IRF-DNA complex reveals novel DNA recognition and cooperative binding to a tandem repeat of core sequences. EMBO J 18, 5028–5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson MH, Cheung D, Rohlfing MM, Kitchens R, Spiegel DE, Tucker J, Battaile JT, Alevy Y, Yan L, Agapov E, Kim EY, Holtzman MJ, 2007. Induction of high-affinity IgE receptor on lung dendritic cells during viral infection leads to mucous cell metaplasia. J. Exp. Med 204, 2759–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Andrew ESL., Lauren ML, Bruce B, Chad N, Michael CZ, Jennifer B, Keri D, Ken D, Michael D, William F, Roel F, Diane G, Katrina, 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, Taniguchi T, 2005. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 434, 772–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Taylor BA, Lee BK, 1982. Organization, distribution, and stability of endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia virus DNA sequences in chromosomes of Mus musculus. J Virol 43, 26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jern P, Sperber GO, Blomberg J, 2005. Use of endogenous retroviral sequences (ERVs) and structural markers for retroviral phylogenetic inference and taxonomy. Retrovirology 2, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao D, Hsu K, Chiu S, Tu V, Chew A, Lee KH, Lee YK, Kwon DN, Greenhalgh DG, Cho K, 2012. ERE database: a database of genomic maps and biological properties of endogenous retroviral elements in the C57BL/6J mouse genome. Genomics 100, 157–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi MM, Goyal P, Maksakova IA, Bilenky M, Leung D, Tang JX, Shinkai Y, Mager DL, Jones S, Hirst M, Lorincz MC, 2011. DNA methylation and SETDB1/H3K9me3 regulate predominantly distinct sets of genes, retroelements, and chimeric transcripts in mESCs. Cell Stem Cell 8, 676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Nakayama K, Penninger J, Kitagawa M, Harada H, Matsuyama T, Tanaka N, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Mak TW, Taniguchi T, 1994. Involvement of the IRF-1 transcription factor in antiviral responses to interferons. Science 264, 1921–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SR, Berson BJ, Risser R, 1988. Mechanism of interaction between endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia viruses in (BALB/c X C57BL/6) hybrid cells. Virology 162, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak CA, 2015. Origins of the Endogenous and Infectious Laboratory Mouse Gammaretroviruses. 7, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger A, Stirnweiss A, Pulverer JE, Klages K, Grashoff M, Reimann J, Hauser H, 2007. Tumor suppression by IFN regulatory factor-1 is mediated by transcriptional down-regulation of cyclin D1. Cancer Res 67, 2972–2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroboshi H, Okubo T, Kitaya K, Nakayama T, Daikoku N, Fushiki S, Honjo H, 2003. Interferon regulatory factor-1 expression in human uterine endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol 91, 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth R, Bannert N, 2010. Beneficial and detrimental effects of human endogenous retroviruses. Int J Cancer 126, 306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais D, Barreiro LB, Gros P, 2016. The macrophage IRF8/IRF1 regulome is required for protection against infections and is associated with chronic inflammation. J. Exp. Med 213, 585–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre C, Tsang J, Bireau C, Heidmann T, Dewannieux M, 2017. A human endogenous retrovirus-derived gene that can contribute to oncogenesis by activating the ERK pathway and inducing migration and invasion. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney NS, Thackray LB, Goel G, Hwang S, Duan E, Vachharajani P, Xavier R, Virgin HW, 2012. Essential Cell-Autonomous Role for Interferon (IFN) Regulatory Factor 1 in IFN-gamma-Mediated Inhibition of Norovirus Replication in Macrophages. J. Virol 86, 12655–12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeney M, Pothlichet J, Renard M, Ducos B, Heidmann T, 2005. Endogenous retrovirus expression is required for murine melanoma tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 65, 2588–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama T, Kimura T, Kitagawa M, Pfeffer K, Kawakami T, Watanabe N, Kundig TM, Amakawa R, Kishihara K, Wakeham A, . 1993. Targeted disruption of IRF-1 or IRF-2 results in abnormal type I IFN gene induction and aberrant lymphocyte development. Cell 75, 83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboko WP, Mounce BC, Emmer J, Darrah E, Patel SB, Tarakanova VL, 2014. Interferon regulatory factor-1 restricts gammaherpesvirus replication in primary immune cells. J. Virol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboko WP, Olteanu H, Ray A, Xin G, Darrah EJ, Kumar SN, Kulinski JM, Cui W, Dittel BN, Gauld SB, Tarakanova VL, 2015. Tumor suppressor IRF-1 counteracts germinal center reaction driven by a cancer-associated gammaherpesvirus. J. Virol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboko WP, Rekow MM, Ledwith MP, Lange PT, Schmitz KE, Anderson S, Tarakanova VL, 2016. IRF-1 and type I interferon cooperate to control acute gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Virol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto M, Fujita T, Kimura Y, Maruyama M, Harada H, Sudo Y, Miyata T, Taniguchi T, 1988. Related expression of a gene encoding a nuclear factor, IRF-1, that specifically binds to IFN-beta gene regulatory elements. Cell 54, 903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa H, Oda E, Nakao K, Ishihara M, Ueda S, Yokochi T, Ogasawara K, Nakatsuru Y, Shimizu S, Ohira Y, Hioki K, Aizawa S, Ishikawa T, Katsuki M, Muto T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N, 1999. Loss of transcription factor IRF-1 affects tumor susceptibility in mice carrying the Ha-ras transgene or nullizygosity for p53. Genes Dev 13, 1240–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa H, Oda E, Ueda S, Tamura G, Maesawa C, Muto T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N, 1998. Functionally inactivating point mutation in the tumor-suppressor IRF-1 gene identified in human gastric cancer. Int. J. Cancer 77, 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oricchio E, Sciamanna I, Beraldi R, Tolstonog GV, Schumann GG, Spadafora C, 2007. Distinct roles for LINE-1 and HERV-K retroelements in cell proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression. Oncogene 26, 4226–4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugheber J, Fredericksen B, Sumpter R Jr., Wang C, Ware F, Sodora DL, Gale M Jr., 2002. Regulation of PKR and IRF-1 during hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyra H, Boni J, Schupbach J, 1994. Ultrasensitive retrovirus detection by a reverse transcriptase assay based on product enhancement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe HM, Kapopoulou A, Corsinotti A, Fasching L, Macfarlan TS, Tarabay Y, Viville S, Jakobsson J, Pfaff SL, Trono D, 2013. TRIM28 repression of retrotransposon-based enhancers is necessary to preserve transcriptional dynamics in embryonic stem cells. Genome Res 23, 452–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T, 2000. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity 13, 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins JW, MacDuff DA, Imanaka N, Gainey MD, Shrestha B, Eitson JL, Mar KB, Richardson RB, Ratushny AV, Litvak V, Dabelic R, Manicassamy B, Aitchison JD, Aderem A, Elliott RM, Garcia-Sastre A, Racaniello V, Snijder EJ, Yokoyama WM, Diamond MS, Virgin HW, Rice CM, 2014. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 505, 691–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM, 2011. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472, 481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocking C, Kozak CA, 2008. Murine endogenous retroviruses. Cell Mol Life Sci 65, 3383–3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T, 2008. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol 26, 535–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Ishihara M, Lamphier MS, Nozawa H, Matsuyama T, Mak TW, Aizawa S, Tokino T, Oren M, Taniguchi T, 1996. Cooperation of the tumour suppressors IRF-1 and p53 in response to DNA damage. Nature 382, 816–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakanova VL, Kreisel F, D.W. W, Virgin HW IV, 2008. Murine gammaherpesvirus-68 genes both induce and suppress lymphoproliferative disease. Journal of Virology 82, 1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakanova VL, Leung-Pineda V, Hwang S, Yang C-W, Matatall K, Basson M, Sun R, Piwnica-Worms H, Sleckman BP, Virgin HW, 2007. Gamma-Herpesvirus Kinase Actively Initiates a DNA Damage Response by Inducing Phosphorylation of H2AX to Foster Viral Replication. Cell Host and Microbe 1, 275–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakanova VL, Suarez FS, Tibbetts SA, Jacoby M, Weck KE, Hess JH, Speck SH, Virgin HW, 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection induces lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma in BALB b2 microglobulin deficient mice. J Virol 79, 14668–14679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang-Johanning F, Radvanyi L, Rycaj K, Plummer JB, Yan P, Sastry KJ, Piyathilake CJ, Hunt KK, Johanning GL, 2008. Human endogenous retrovirus K triggers an antigen-specific immune response in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res 68, 5869–5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Goff SP, 2017. Differential control of retrovirus silencing in embryonic cells by proteasomal regulation of the ZFP809 retroviral repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E922–E930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Jovel J, Halloran B, Wine E, Patterson J, Ford G, O’Keefe S, Meng B, Song D, Zhang Y, Tian Z, Wasilenko ST, Rahbari M, Reza S, Mitchell T, Jordan T, Carpenter E, Madsen K, Fedorak R, Dielemann LA, Ka-Shu WG, Mason AL, 2015. Metagenomic analysis of microbiome in colon tissue from subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases reveals interplay of viruses and bacteria. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis 21, 1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu DP, Chen PP, Koeffler HP, Tong XJ, Xie D, 2007. Involvement of IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and IRF-2 in the formation and progression of human esophageal cancers. Cancer Res 67, 2535–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, Agarwala R, Ainscough R, Alexandersson M, An P, Antonarakis SE, Attwood J, Baertsch R, Bailey J, Barlow K, Beck S, Berry E, Birren B, Bloom T, Bork P, Botcherby M, Bray N, Brent MR, Brown DG, Brown SD, Bult C, Burton J, Butler J, Campbell RD, Carninci P, Cawley S, Chiaromonte F, Chinwalla AT, Church DM, Clamp M, Clee C, Collins FS, Cook LL, Copley RR, Coulson A, Couronne O, Cuff J, Curwen V, Cutts T, Daly M, David R, Davies J, Delehaunty KD, Deri J, Dermitzakis ET, Dewey C, Dickens NJ, Diekhans M, Dodge S, Dubchak I, Dunn DM, Eddy SR, Elnitski L, Emes RD, Eswara P, Eyras E, Felsenfeld A, Fewell GA, Flicek P, Foley K, Frankel WN, Fulton LA, Fulton RS, Furey TS, Gage D, Gibbs RA, Glusman G, Gnerre S, Goldman N, Goodstadt L, Grafham D, Graves TA, Green ED, Gregory S, Guigo R, Guyer M, Hardison RC, Haussler D, Hayashizaki Y, Hillier LW, Hinrichs A, Hlavina W, Holzer T, Hsu F, Hua A, Hubbard T, Hunt A, Jackson I, Jaffe DB, Johnson LS, Jones M, Jones TA, Joy A, Kamal M, Karlsson EK, Karolchik D, Kasprzyk A, Kawai J, Keibler E, Kells C, Kent WJ, Kirby A, Kolbe DL, Korf I, Kucherlapati RS, Kulbokas EJ, Kulp D, Landers T, Leger JP, Leonard S, Letunic I, LeVine R, Li J, Li M, Lloyd C, Lucas S, Ma B, Maglott DR, Mardis ER, Matthews L, Mauceli E, Mayer JH, McCarthy M, McCombie WR, McLaren S, McLay K, McPherson JD, Meldrim J, Meredith B, Mesirov JP, Miller W, Miner TL, Mongin E, Montgomery KT, Morgan M, Mott R, Mullikin JC, Muzny DM, Nash WE, Nelson JO, Nhan MN, Nicol R, Ning Z, Nusbaum C, O’Connor MJ, Okazaki Y, Oliver K, Overton-Larty E, Pachter L, Parra G, Pepin KH, Peterson J, Pevzner P, Plumb R, Pohl CS, Poliakov A, Ponce TC, Ponting CP, Potter S, Quail M, Reymond A, Roe BA, Roskin KM, Rubin EM, Rust AG, Santos R, Sapojnikov V, Schultz B, Schultz J, Schwartz MS, Schwartz S, Scott C, Seaman S, Searle S, Sharpe T, Sheridan A, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Singer JB, Slater G, Smit A, Smith DR, Spencer B, Stabenau A, Stange-Thomann N, Sugnet C, Suyama M, Tesler G, Thompson J, Torrents D, Trevaskis E, Tromp J, Ucla C, Ureta-Vidal A, Vinson JP, Von Niederhausern AC, Wade CM, Wall M, Weber RJ, Weiss RB, Wendl MC, West AP, Wetterstrand K, Wheeler R, Whelan S, Wierzbowski J, Willey D, Williams S, Wilson RK, Winter E, Worley KC, Wyman D, Yang S, Yang SP, Zdobnov EM, Zody MC, Lander ES, 2002. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf D, Goff SP, 2009. Embryonic stem cells use ZFP809 to silence retroviral DNAs. Nature 458, 1201–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinobu K, Baudino L, Santiago-Raber ML, Morito N, Dunand-Sauthier I, Morley BJ, Evans LH, Izui S, 2009. Selective up-regulation of intact, but not defective env RNAs of endogenous modified polytropic retrovirus by the Sgp3 locus of lupus-prone mice. Journal of Immunology 182, 8094–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young GR, Eksmond U, Salcedo R, Alexopoulou L, Stoye JP, Kassiotis G, 2012. Resurrection of endogenous retroviruses in antibody-deficient mice. Nature 491, 774–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Lubben W, Slomka H, Gebler J, Konert M, Cai C, Neubrandt L, Prazeres da Costa O, Paul S, Dehnert S, Dohne K, Thanisch M, Storsberg S, Wiegand L, Kaufmann A, Nain M, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Bettio S, Schnierle B, Kolesnikova L, Becker S, Schnare M, Bauer S, 2012. Nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors are essential for the control of endogenous retrovirus viremia and ERV-induced tumors. Immunity 37, 867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]