Abstract

The evidence base of policies that improve the timeliness of cancer care is under ongoing debate. Pancreatic cancer is frequently diagnosed in a stage when curative therapy is not feasible; hence, it is an important target for timelier healthcare interventions. The objectives of our research were to identify all clinical studies on pancreatic cancer care delays via a systematic literature review, to assess the study methodologies for possible biases, to conclude on the available evidence, and to formulate research recommendations on evidence gaps. Nineteen studies were identified and eight reported multivariate analyses. Although many sources of bias shifted the results towards negative or paradoxical findings, a statistically significant association of shorter delays with better clinical outcomes was demonstrated in the majority of studies reporting multivariate analyses. Noninferiority analyses were not published. Further efforts to provide timely care for pancreatic cancer patients are encouraged, and studies on the associations of delay with patient experience and healthcare resource utilization are warranted.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, delay, wait time, prognosis, bias, systematic review

Introduction

Patient navigation programs aim to improve outcomes in vulnerable populations by eliminating barriers to the timely diagnosis and treatment of cancers or other chronic diseases.1 The first patient navigation program in the USA was launched in 1990 at the Harlem Hospital Center in New York City, with the ambition of providing free or low-cost examinations and mammograms and patient navigation to achieve timely diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer. After introducing the program, the proportion of breast cancer patients with stage 3–4 disease at diagnosis decreased from 49% to 21%, and their 5-year survival rate improved from 39% to 70% at this center.1 This program also showed that important patient-level barriers linked with socioeconomic deprivation as well as the capacity and organization of the medical system itself may also limit the timeliness of cancer care provision. Several patient navigation demonstration sites have been established in the USA.1,2 In parallel, many European countries with almost full health insurance coverage have made strong efforts for timely cancer care, mostly focusing on the capacity barriers of their generous medical systems. In the UK, cancer waiting time targets were introduced in 2000 as part of the NHS Cancer Plan, setting upper limits for the time to the first specialist visit (14 days) and to treatment initiation (62 days).3 Similarly, the 2015 National Cancer Program in Sweden specified time bounds for patient pathway intervals starting from the event of “well-founded suspicion” defined for each cancer type separately.4 Nevertheless, the evidence basis of introducing delay thresholds for cancer patient pathway intervals is frequently challenged in the scientific literature and may be different according to different cancer types.5–7 Randomized controlled studies are scarce in this field. While many observational studies reported associations of shorter delays with better clinical outcomes in symptomatic cancers, others found paradoxical associations of longer delays with better outcomes.8 Such paradoxical associations may result from multiple sources of methodological bias, as overviewed and explained in Table 1. The contradictory findings may also reflect the wide heterogeneity in study populations, delay definitions, differences in delays across cohorts, and sample sizes across studies.

Table 1.

Sources Of Potential Bias

| Bias Type (Reference) | Explanation | Bias Direction | How To Control For The Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting time paradox8,20 | Patients with the most severe/aggressive disease receive earlier care and have worse prognosis. | Paradoxical association of longer delays with better outcomes. | Assign delays by randomization; or exclude patients who are diagnosed very quickly and/or have very poor outcomes, e.g., early death. |

| Lead time bias21 | Earlier detection of the same cancer results in apparently longer survival, even if the natural history of the tumor is unaltered. | Apparently longer survival in patients with earlier diagnosis. | In time to event analyses, carefully select comparable clock start events in study arms/cohorts. |

| Length bias21 | Patients with most aggressive disease may die before diagnosis/treatment initiation; hence, they may be underrepresented in cohorts with longer delays. | Paradoxical association of longer delays with better outcomes. | Report and consider the proportions of discontinued/excluded patients by reasons. |

| Confounding22–24 | Patients with shorter and longer delays may systematically differ in measurable or unmeasurable confounders. Residual heterogeneity may persist after randomization/matching. | Bias may occur in both directions. | By design: randomized allocation of delays in care. By analysis: matching or weighting of the compared populations for measurable confounders before analysis; adjustment for measurable confounders in multivariate analysis. |

| Adjustment for parameters in the putative causal chain24,25 | Adjusting for intermediate outcomes may hide the association with the final outcome. | False negative findings on delay-outcome associations. | Do not adjust multivariate analyses for intermediate outcomes, i.e., for dependent variables in the putative causal chain. |

Cancer of the exocrine pancreas is one of the leading causes of cancer mortality in developed countries and is one of the most lethal malignant neoplasms worldwide.9,10 Unfortunately, the mortality of pancreatic cancer is almost identical with its incidence since most patients with pancreatic cancer are diagnosed in a locally advanced or metastatic stage when the only curative treatment option, complete surgical resection, is no longer feasible.11–13 In theory, improvements in the timely diagnosis and treatment initiation of pancreatic cancer may contribute to better patient prognosis, given the following findings: i) the progression time of pancreatic adenocarcinomas from stage T1 to T4 is estimated to be just over 1 year;14 ii) large (>2 cm) pancreatic cancers develop CT-detectable metastases in a mean period of 3.5 months (range 1.2–8.4 months);15 and iii) assuming exponential tumor growth, the speed of tumor cell replication is highest in the last weeks of its natural course before treatment initiation.16 Screening opportunities for pancreatic cancer are not available at present. Accordingly, symptomatic pancreatic cancer patients with long wait times could theoretically benefit from shorter delays and earlier diagnosis and treatment. However, many studies reported statistically significant paradoxical associations of longer wait times with better clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients.17–19

To navigate the jungle of contradictory evidence in this important field, we conducted a systematic literature review of all published studies on the association of delays in care with outcomes in patients with cancer of the exocrine pancreas, with the following objectives: 1. to identify the potential sources of methodological bias in each study; 2. to synthetize the available evidence, taking into account the recognized sources of methodological bias; and 3. to formulate recommendations for further research on current evidence gaps. The review was not limited to specific interventions, comparators, outcomes, study designs, or healthcare settings.

Materials And Methods

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review was conducted in 5 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, LISTA, and Library of Congress) to identify original research papers on the association of the delay in pancreas adenocarcinoma care with patient-level outcomes, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (the PRISMA checklist is provided in Table S6). Search strings for PubMed and Scopus were composed of a combination of search terms related to pancreatic cancer and delayed care, while the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews search covered all pancreas-related papers. LISTA and Library of Congress were searched for all articles related to pancreatic cancer. For the specific search syntax, please see Table S1 in the online supplementary materials; searches were conducted for the 2000–2017 period. Search records were deduplicated and then underwent title and abstract screening by two independent researchers using EndNote software, and conflicting opinions were resolved by a senior researcher. Papers without an English abstract, not related to cancer of the exocrine pancreas, and/or without original research findings (e.g., nonsystematic reviews) were excluded in the screening phase. Periampullary cancer findings with mixed or unknown histology were included for the sake of completeness, whereas studies solely on ampullary and/or bile duct cancers were excluded. The protocol of this systematic review has not been registered.

All records passing the title-abstract screening were read in full text and checked for eligibility by two researchers. The eligibility criteria in the full text review phase were pancreatic cancer papers with data on the delay of care and at least one outcome reported as a function of delay. Non-peer-reviewed papers, conference posters, and records not available in full text were also excluded. The reference lists of all eligible records were examined for additional relevant articles that underwent the same screening and full text review process as described above. Data extraction on study characteristics, study populations, delay definitions and durations, and study outcomes was completed by one researcher and checked by another researcher. The investigators of the studies were not contacted to obtain missing data in their publications.

Assessment Of Possible Sources Of Bias

The quality assessment of the identified records is an inherent part of systematic literature reviews.26 The possible risk of bias was characterized using the Cochrane Collaboration Quality Assessment Tool for randomized and controlled studies and the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) instrument for nonrandomized studies.27 In both quality assessment tools, the judgments on the risk of bias were made by a single reviewer and were double-checked by another reviewer. Beyond the above generic bias assessment tools, we carefully assessed the risk of specific biases previously described in this research context (Table 1). The risk of bias due to the wait time paradox was excluded if the duration of care delay was assigned by randomization or if patients diagnosed very quickly and/or having very poor outcomes (e.g., early death) were excluded from the analyses.8,20 Lead time bias reflects the apparent improvement in survival when survival time is measured from an earlier time point in natural history.21 Lead time bias was excluded in survival analyses where the clock start event was not shifted by differences in care delay, e.g., measured from the presentation of symptoms or from the time of randomization. Moreover, the risk of lead time bias was considered low if the between-cohort difference in survival was clearly longer than the observed shift of the clock-start event. Length bias reflects the higher mortality of more severe patients and hence the enrichment of patients with less aggressive disease in cohorts with longer delays of care.21 Length bias was excluded in studies with complete follow-up of patients until the study endpoint. The risk of confounding22,24 was considered to be high in studies without multivariate analyses and low in studies with multivariate analyses adjusted for primary tumor histology and for the location within the pancreas or type of initial symptoms. The risk of bias due to adjustment for parameters in the putative causal chain was raised when multivariate analyses were adjusted to interim outcomes, e.g., survival analyses adjusted to tumor staging parameters or resectability at the end of the investigated delay periods.24,25

Results

Systematic Search Results

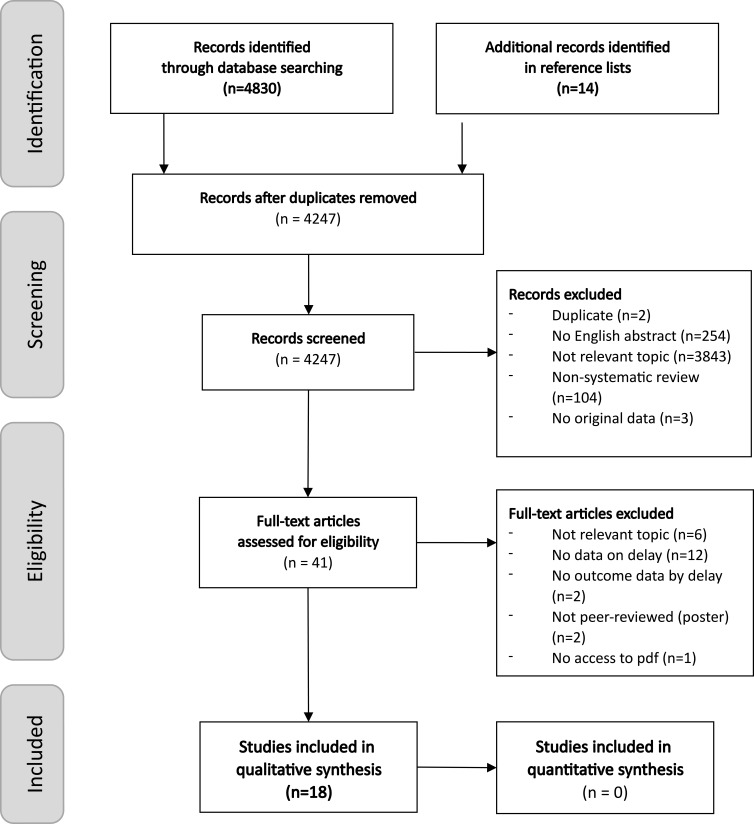

The numbers of identified, screened and excluded papers are shown in the PRISMA flowchart28 in Figure 1. Altogether, 18 pancreatic cancer studies were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. The key characteristics of the included studies are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Most studies were single-center retrospective analyses. The included studies applied a wide range of outcome and delay definitions as well as statistical analysis methods and involved various study populations (e.g., by cancer histology, stage distribution, and extent of delay). Delay periods were measured from symptom onset in 6 studies, from the first specialist consultation in 2 studies, from the first or last cross-sectional imaging in 9 studies, and from cancer diagnosis in 1 study. The delay distributions within studies were typically right-skewed; therefore, the mean values are hardly informative — note that when reported, the standard deviation was always higher than the mean delay (Table 2). Many studies reported only proportions above certain delay thresholds. Quartiles and medians provide more detailed information on nonnormal distributions. No clear trend could be identified in the median delay values over time or across countries. Instead, initial misdiagnosis was reported for 60%, 31.3%, and 9% of patients in studies from Greece, the US, and Germany, respectively;30,31,40 adequate care provision for these patients could be postponed by a couple of months: their median diagnostic delay was in the 3–5 month range, and 25% experienced a diagnostic delay of >6.3 months in the US and >10 months in Germany. The most extreme delays were reported as a 24-month diagnostic delay in Germany and an 18.4-month treatment delay in the UK (Table 2). For details on the enrolled patient populations and for a narrative summary of the key study findings, please see Tables S2 - S4 in the online Supplementary Materials. Potential methodological biases identified in the included studies are detailed in Section 3.2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic literature review.

Table 2.

Extent Of Patient, Diagnostic, And Treatment Delays In Pancreatic Cancer Care

| Study | Country | Years | Cohort | Mean (SD) in Months* | Median (IQR) In Months* | Range In Months* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient delay (from first symptom to first visit) | ||||||

| 19 | Japan | 1991–2000 | All patients | 1.4 (1.8) | 0.7 (0.1–2) | NA |

| 30 | Greece | 1994–2000 | Initial dg. (40%) | NA | 1 (NA) | NA |

| Initial misdg. (60%) | NA | 1.4 (NA) | NA | |||

| 36 | Canada | 2000–2008 | Resectable (61.7%) | 1.2 (1.6) | NA | NA |

| Unresectable (38.3%) | 1.7 (3.2) | NA | NA | |||

| 31 | US | 2000–2010 | Initial dg. (68.7%) | NA | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | NA |

| Initial misdg. (31.3%) | NA | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | NA | |||

| Diagnostic delay (from first visit to diagnosis) | ||||||

| 30 | Greece | 1994–2000 | Initial dg. (40%) | NA | 0 (NA) | NA |

| Initial misdg. (60%) | NA | 3 (NA) | NA | |||

| 40 | Germany | 1994–2000 | Initial misdg. (9%) | NA | 5 (2–10) | 1–24 |

| 31 | US | 2000–2010 | Initial dg. (68.7%) | NA | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | NA |

| Initial misdg. (31.3%) | NA | 3.5 (1.6–6.3) | NA | |||

| Patient delay + diagnostic delay | ||||||

| 32 | Italy | 2001–2010 | All patients | NA | 2.0 (NA) | 0.1–10.4 |

| Treatment delay from first cross-sectional imaging | ||||||

| 33 | UK | 2006–2014 | All patients | NA | 1.6 (NA) | 0.0–18.4 |

| 41 | Canada | 2008–2012 | 1 imaging test (21.5%) | 1.5 (NA) | NA | NA |

| 2 imaging tests (42.3%) | 1.8 (NA) | NA | NA | |||

| 3 imaging tests (23.8%) | 2.0 (NA) | NA | NA | |||

| 4 imaging tests (5.4%) | 2.7 (NA) | NA | NA | |||

| 5 imaging tests (6.2%) | 4.1 (NA) | NA | NA | |||

| 29 | Sweden | 2008–2014 | All patients | NA | 1.4 (NA) | 0.3–5.3 |

| 34 | Ireland | 2010–2015 | Resected (87.9%) | NA | 1.0 (NA) | NA |

| Unexpected progression (12.1%) | NA | 1.5 (NA) | NA | |||

| Treatment delay from latest cross-sectional imaging | ||||||

| 18 | Netherlands | 2003–2008 | Randomized to early surgery | 0.3 (NA) | NA | NA |

| Randomized to preoperative biliary drainage | 1.2 () | NA | NA | |||

| 42 | US | 2004–2009 | Proximal, not metastatic | 0.6 () | NA | 0.0–2.9 |

| Proximal, metastatic | 0.8 (NA) | NA | ||||

| 43 | US | 2006–2007 | All patients | NA | 0.5 (NA) | 0.0–6.6 |

Notes: *Data provided in days or weeks were converted by applying a 30-day per month ratio.

Abbreviations: Dg, diagnosis; IQR, interquartile range.

Bias Assessment Results Using Generic Tools

The single randomized controlled trial18 had a low risk of bias in all aspects considered by the Cochrane tool. For the nonrandomized comparative studies, MINORS scores ranged from 1339 to 20,34 where the scale range was 0 to 24 (the higher the better). Zero scores were typical for the blinded evaluation of endpoints, prospective calculation of study size and power, and baseline equivalence of groups. For details, please see Table S5 in the online Supplementary Materials. No study was excluded from the narrative synthesis based on these findings.

Assessment Of Specific Sources Of Potential Bias

The waiting time paradox was not explicitly mentioned in any of the identified studies. None of the studies excluded patients with very short wait times from the main or sensitivity analyses, and only one study excluded patients with the worst prognoses (in-hospital and 30-day mortality) from the survival analyses.29 The randomized controlled design is an efficient way of controlling for the wait time paradox in between-arm comparisons. However, some residual biases cannot be excluded in the regression analyses of an RCT study population since the within-arm heterogeneity also shapes these results; and for instance, in the study by Eshuis et al, randomization was overwritten by clinical decisions in approximately 4% of study participants.18

The lead time bias was adequately controlled for in 2 studies, and these studies calculated the length of survival from the presentation of symptoms30 or from the time of randomization.18 In other studies, survival was calculated from the time of diagnosis31–33 or from the time of surgery,17,29,34 or the clock start event was not specified.35–38 Five studies reported statistically significant survival benefits in patients with shorter care delays. The extent of lead time bias was probably marginal in four of these, due to the survival period definition30 or to substantially larger survival benefits than the observed differences in delays.32,37,38 However, one study reported a minor but statistically significant survival benefit (approximately 2-month difference in median survival, p=0.014) in a sensitivity analysis of patients with <143 days versus >143 days from symptom onset to referral letter.35 Since the survival measurement clock start event was not reported in this study and the apparent survival benefit was comparable in size to the difference in delays, this finding could reflect lead time bias.

Length bias could not occur in studies without dropouts.19,29–31,39–41 However, many studies excluded all patients from the analyses who did not complete the diagnostic phase32 or did not undergo surgery18,33,34,36–38,42,43 or other treatment.17,35 Given that patients with the most aggressive disease may die or may become inoperable in higher proportions in cohorts with longer delay periods, these studies are subject to length bias.

Confounding was controlled by randomized design in only one study;18 unfortunately, this study had a significant baseline imbalance of patient age and BMI. None of the studies applied the matching or weighting of cohort populations before analysis to enforce comparability in terms of measurable and related confounders, but the study inclusion criteria occasionally restricted the study populations by histology type or tumor stage. Only 8 of the 18 included studies reported multivariate analyses on the association of delayed care with outcomes. Many of these failed to adjust for histology and primary location or type of initial symptoms (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analyses Of Delayed Care Associations In Pancreatic Cancer

| Study | Analyzed Population | Outcome Parameter | Findings In Multivariate Analyses | Potential Sources Of Confounding, And/Or Adjustment For Intermediate Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Pancreatic cancer | Time from first symptom to first consultation >30 days | Presence of metastasis: OR 1.2 (95% CI 0.8–1.8). Adjusted for age, sex, and type of initial symptoms#. | Not controlled for histology type and time from first consultation to metastasis status assessment. |

| Time from first consultation to first treatment >29 days | Presence of metastasis: OR 0.5 (95% CI 0.3–0.9)#§. Treatment type: medical bypass OR 0.7 (95% CI 0.3–1.7), chemo- or radiotherapy OR 2.1 (95% CI 1.0–4.4). Adjusted for age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, type of initial symptoms#, type of first practitioner (GP/gastroenterologist/emergency room#/other), and socioeconomic quintiles. | Not controlled for histology type and time from first symptom to first consultation. Wait time paradox; length bias (untreated patients excluded). | ||

| Overall survival | Time from first symptom to first consultation >30 days: HR 1.09 (95% CI 0.74–1.63); Time from first consultation to treatment ≥29 days: HR 0.73 (95% CI 0.51–1.06); Both periods above the thresholds: HR 0.84 (95% CI 0.60–1.17). Adjusted for age#, sex, socioeconomic quintiles, and stage/radicality of surgery (M0 with R0/M0 without R0/M1)#. | Not controlled for histology type, and for location within the pancreas or type of initial symptoms. Adjusted for intermediate outcomes (complete resection and presence of distant metastasis). Wait time paradox; length bias (untreated patients excluded). |

||

| 18 | Periampullary cancers of any histology, serum total bilirubin 2.3–14.6 mg/dL, no CT evidence of locoregional irresectable or metastatic disease, all patients who underwent surgery | Overall survival | Time from randomization to surgery in weeks: HR 0.91 (95% CI 0.84–0.99)#§. Adjusted for age, sex, bilirubin quartiles at randomization#, resection of tumor, intraoperative blood transfusion, and surgery complications. |

Adjustment by design (RCT) was imperfect, imbalance in sex and in BMI. Not controlled for histology in the analyses. Adjusted for an intermediate outcome (tumor resectability at surgical exploration). Length bias (patients not undergoing surgery were excluded). |

| Subgroup undergoing resection surgery | Time from randomization to surgery in weeks: HR 0.85 (95% CI 0.75–0.96)#§. Adjusted for age, sex, histology (PDAC/other)#, nodal status#, microscopically residual disease (R1)#, bilirubin quartiles at randomization#, and surgery complications#. | Adjustment by design (RCT) was imperfect, imbalance in sex and BMI. Adjusted for intermediate outcomes (nodal status and microscopically residual disease). Length bias (patients not undergoing resection surgery were excluded). | ||

| 19 | All solid organ cancers | Presence of metastasis at diagnosis | Time from first symptom to first visit in months: OR 0.97 (95% CI 0.96–0.99)#§. Adjusted for age groups# and sex#. | Not controlled for primary organ, histology type, location within the pancreas or type of initial symptoms, and delay from first visit to diagnosis. Wait time paradox. |

| 29 | Surgical candidates with PDAC deemed resectable by imaging | Presence of unresectable disease | Time from imaging to resection ≤32 days: OR* 0.35 (95% CI 0.14–0.90)#. Adjusted for preoperative tumor size (<30 mm)# and preoperatively assessed vascular involvement (no or minor)#. | Not controlled for age, sex, location within the pancreas or type of initial symptoms. No adjustment for intermediate outcomes. Controlled for length bias and for the wait time paradox. |

| 32 | Pancreatic cancer, stratified by chemotherapy | Overall survival | Time from symptoms to diagnosis in weeks: HR 1.0240 (95% CI 1.0117–1.0365)#. Adjusted for age, sex, location within the pancreas (head/other), histology (PDAC/other), stage (I+II/III+IV), size#§, and surgery type (radical resection/other)#. | Adjusted for an intermediate outcome (radical resection). Tumor size and stage could also be intermediate outcomes if determined after diagnosis from surgery specimens. Wait time paradox; length bias (patients with incomplete diagnostics were excluded). |

| 35 | PDAC; all periampullary tumors excluded | Overall survival | Time from symptoms to referral in days: HR 1.001, 95% CI 1.000–1.002, p=0.010)#; time from referral to treatment: NS, HR not reported. Adjusted for age, sex, type of initial symptoms, operability, resectability#. | Adjusted for intermediate outcomes (operability and resectability). Wait time paradox; length bias (patients not receiving treatment were excluded). Risk of lead time bias in sensitivity analysis of a 143-day threshold for patient delay. |

| 38 | Pancreatic cancer patients undergoing definitive surgery | Overall survival | Time from diagnosis to definitive treatment >31 days: HR 1.23 (95% CI 1.07–1.41)#. Adjusted for age, sex, Charlson comorbidity score, hospital type, insurance, radiotherapy after definitive surgery, chemotherapy after definitive surgery, type of medical care institution, hospital volume#, and year of diagnosis. (No information on the significance of covariates except for hospital volume). |

Not controlled for histology and for location within the pancreas or type of initial symptoms. Adjusted for intermediate outcomes (having radiotherapy and chemotherapy after definitive surgery, probably due to incomplete resection). Wait time paradox; length bias (patients not receiving treatment were excluded). |

Notes: # statistically significant association; § paradoxical association; * Reported as HR but is most likely OR based on the study methods.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Adjustment for parameters in the putative causal chain occurred in all but one multivariate analysis (Table 3), diluting or diminishing the association of longer care delays with worse prognosis.

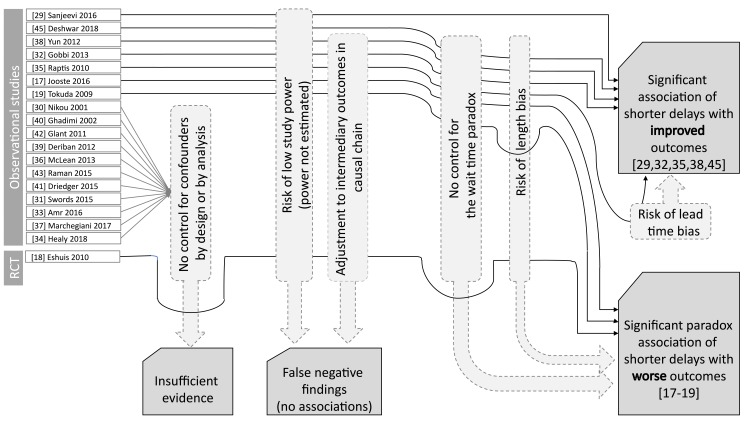

Overview Of Study Results

Multivariate analyses of the identified studies are summarized in Table 3. Although multiple sources of bias shifted the results towards negative or paradoxical findings, a statistically significant association of shorter delays with better clinical outcomes was demonstrated in five of eight studies reporting multivariate analyses (Figure 2). For detailed interpretation of study findings and methodology biases together with their narrative synthesis, please see the Discussion section.

Figure 2.

Overview of key study findings and sources of potential methodological bias.

Discussion

To the extent of the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest systematic literature review on the association of care delay with patient outcomes in pancreatic cancer. For comparison, recent systematic reviews of care delays in all solid organ cancers included five8 and two44 pancreatic cancer studies. An interpretation of the available evidence and research recommendations are provided below.

Interpretation Of The Available Evidence

All of the 18 included studies suffered from one or more sources of potential methodological bias. Nonrandomized studies without matching/weighting of the compared populations and without multivariate analyses are particularly susceptible to bias, thus providing low-quality evidence. The single randomized controlled study found statistically significant paradoxical associations: every week of postponing surgery decreased the hazard of mortality by 9% in periampullary cancer patients without CT evidence of locoregional irresectable or metastatic disease.18 Nevertheless, this analysis was adjusted for resectability (67% in the early surgery arm and 56% in the postponed surgery arm), an intermediate outcome that could hide the true association of delays with the mortality hazard. Similarly, the subgroup analysis of resection surgery patients showed that every additional week of postponing surgery decreased the hazard of mortality by 15% when adjusted for intermediate outcomes (microscopically residual disease and tumor-positive lymph nodes) that occurred less frequently in the early surgery arm (27% vs. 38% and 65% vs. 70%, respectively). These paradoxical findings clearly indicate that the randomized controlled study design alone is not a guarantee for an unbiased effect estimation, and careful consideration is needed regarding the analytical methods to apply. Some nonrandomized studies with multivariate analyses also reported statistically significant paradoxical associations. Tokuda et al found that every month of patient delay was associated with an approximately 3% reduction in the remote metastasis odds at diagnosis;19 however, this analysis pooled all solid organ cancers and did not adjust for the primary organ or histology. Jooste et al found that a >29-day delay from the first consultation to first treatment was associated with a 50% lower hazard of remote metastasis but did not adjust for histology type, location within the pancreas, or patient delay.17 These studies were not controlled for the wait time paradox, and the latter study was subject to length bias, providing multiple arguments to explain the above clinically nonsensical associations. The largest nonrandomized study with multivariate analysis was published by Yun et al, who retrospectively analyzed 2309 patients and found that a >31-day delay from diagnosis to definitive treatment was associated with an ~23% increase in mortality hazard when adjusted for several covariates but not for histology and tumor location within the pancreas.38 Gobbi et al reported that every additional week of delay from the first symptom to diagnosis was associated with an ~2.4% increase in mortality hazard, adjusted for age, sex, location within the pancreas, histology, stage, size, and surgery type.32 Raptis et al investigated nonperiampullary PDAC patients only and found that every day of patient delay was associated with a minor but statistically significant increase in mortality hazard, whereas the time from the first referral to treatment showed no significant association with mortality.35 The authors stated that “multivariate analysis excluded that the time from referral to treatment was an independent predicting factor of survival (p=0.108)”, which was a controversial conclusion for two reasons. First, a statistically nonsignificant finding is not evidence against the association in general but may result from insufficient statistical power or confounding by intermediate outcomes (e.g., operability and resectability in this analysis). Second, it is biologically unreasonable that the time before but not after the first medical referral is important. Such an inference would assume that the tumor changes its behavior at the first medical visit. Notably, the true associations could be even stronger in these studies due to the waiting time paradox, length bias, and adjustment for one or more intermediate outcomes (Table 3). The single nonrandomized study that controlled both for the wait time paradox and length bias and did not adjust for intermediate outcomes in multivariate analyses was published by Sanjeevi et al.29 This study investigated the association of the imaging-to-resection/reassessment (IR) interval with progression to locally advanced/metastatic disease incompatible with curative resection in 349 surgical candidate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients. The unresectability rate was zero in patients with IR ≤22 days and was significantly lower for IR interval ≤32 days compared with longer waiting times (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21–0.89). In patients with resection surgery, an IR interval ≤32 days was not significantly associated with a reduced mortality hazard (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.61–1.26). Given that unresectability is known to be a strong predictor of mortality in PDAC, the latter finding may reflect the low statistical power of this study but also that if the tumor is operated in the resectable stage, then IR does not have a prognostic role. In contrast, as the main result shows, IR is a strong determinant of resectability.

Recently, Deshwar et al published a relevant study beyond the inclusion period of our systematic literature review.45 They conducted a retrospective chart review of 116 PDAC patients and investigated the association of patient, diagnostic, and treatment delays with surgical resectability rates. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race and all delay periods by thresholds, patient delay ≤30 days and diagnostic delay ≤60 days were significant predictors of resectability (OR 3.41, 95% CI 1.08–13.2; and OR 15.68, 95% CI 2.95–291.00, respectively), while treatment delay ≤30 days was not (OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.68–5.01). This study did not control for the wait time paradox and excluded all untreated patients; therefore, it was subject to length bias, and hence, the true association of delays with resectability could be even stronger.

Overall, a narrative evidence synthesis is provided since heterogeneity in definitions and populations as well as methodological limitations prevents performing a meta-analysis of studies. Lead time bias could have a marginal contribution to the positive associations of shorter care delays with survival. Even though none of the studies reported statistical power calculations, and 7 of 8 studies suffered from other biases that shifted results towards negative and paradoxical findings, 5 of 8 studies showed a statistically significant association of delayed pancreatic cancer care with adverse clinical consequences, especially in patients with potentially curable disease (Figure 2). Importantly, all studies tested the “superiority” of shorter delays, with a null hypothesis that shorter delays do not cause better outcomes. The lack of statistically significant findings in these superiority analyses shall be interpreted as there is no statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis. Such findings do not confer, however, enough evidence against the tested associations, i.e., they do not rule out that a shorter delay causes a better outcome; they simply do not provide enough evidence for that conclusion. This is especially true for studies with small sample sizes and low statistical power. Power calculations were not reported in any of the identified studies; hence, the risk of low study power cannot be ruled out. Instead of superiority analyses, other types of statistical methods, such as “noninferiority” and “equivalence” analyses, would be warranted to exclude the clinical benefits of earlier diagnosis and treatment with high probability, based on predefined equivalence margins.46,47 However, none of the identified studies reported corresponding analyses, testing the hypotheses of whether care with longer delays confers not worse or equivalent outcomes compared with care with shorter delays. Concluding equivalence or noninferiority based on nonsignificant test results in superiority analyses is clearly inappropriate.47 Hence, we conclude that continuous efforts to provide timely care for patients with suspected pancreatic cancer are supported by empirical evidence, while there is no valid scientific rationale behind opposing statements/recommendations at present.

Notably, all studies focused on clinical outcomes, e.g., stage distribution, resectability and overall survival, even though patient experience of the care process and healthcare resource utilization are also important aspects to consider in health policy decisions, according to the framework of the Triple Aim in Healthcare.48 This is a critical evidence gap: the overall value of improving the timeliness of pancreatic cancer care cannot be reliably evaluated from the health economic perspective without these considerations. The additional costs of capacity development in a healthcare system and impacts on patient experience in the care process also need to be carefully considered when forming health policy decisions on interventions to improve timely access to cancer care.

An inherent limitation of our review is that the identified studies were typically not randomized and controlled. Given that early diagnosis and treatment is thought to be associated with longer patient survival, the implementation of randomized controlled studies on the impact of longer delays in pancreatic cancer is hardly acceptable from the ethical perspective. Hence, observational studies have an important role in evidence generation despite their methodological limitations. The included observational studies suffered from multiple sources of potential bias, mostly predisposing them to negative or paradoxical findings, as well as applied heterogeneous delay and outcome definitions that prevented the quantitative integration of findings across studies. However, our systematic review methodology was sound and robust, and the potential sources of methodological bias were taken into account in a systematic manner in the narrative synthesis. Accordingly, the following research recommendations and conclusions were formed based on the best level of current evidence regarding the impact of care delays in cancer of the exocrine pancreas.

Research Recommendations

Future studies should consider and adequately discuss the wait time paradox, length bias, lead time bias, and confounding bias and should not adjust multivariate analyses for intermediate outcomes in the putative causal chain. The effect of delay on disease prognosis should be studied specifically by cancer types. The adequate prevention of confounding might be achieved by matching or weighting the study groups for prognostic factors at the start; however, in practice, controlling for them in the analysis is more feasible and efficient. Tumor progression indicators (e.g., stage or resectability) at the start of the investigated delay period are important to control for in order to enhance the comparability across cohorts. However, the same indicators measured at later time points, e.g., at the end of the investigated delay period, should be regarded as intermediate outcomes in the causal chain to longer-term benefits, including patient survival. Beyond clinical outcomes, patient experience as well as resource utilization and care costs also need to be investigated to support health economic analyses and subsequent evidence-based health policy decisions. The extrapolation of study findings to other populations and health systems also needs to be critically assessed, keeping in mind the differences in study populations and current performance of healthcare systems, e.g., different length of wait lists.

Conclusions

Care delays show right-skewed distributions due to patient subgroups with unusually long patient, diagnostic, and/or treatment delays. Despite the methodological limitations of the available studies, the clinical advantage of reducing long care delays in pancreatic cancer patients is supported by empirical evidence, especially in patients with potentially curable disease. None of the published analyses were designed to prove the opposite statement. To support health economic analyses and evidence-based health policy decisions on patient navigation programs for pancreatic cancer patients, further research is warranted on patient experience outcomes and on healthcare resource utilization, as well as on the costs of capacity development.

Acknowledgments

Native speaker review of the manuscript was provided by American Journal Experts (www.aje.com), verification code 5908-518F-4C1C-372B-1DCC.

Disclosure

The employers of the coauthors received public funding for qualitative and quantitative studies on a patient navigation program (OnkoNetwork) from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 634288 (project acronym: SELFIE). Mr Marcell Csanádi report grants from Syreon Research Institute, during the conduct of the study; Dr Mariann Moizs report grants from Grant Agreement No. 634288 from the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, outside the submitted work; Professor Zoltán Kaló report grants from European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program, during the conduct of the study; Professor Zoltán Vokó report other from Syreon Research Institute, outside the submitted work; Dr János György Pitter report grants from European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3537–3540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v117.15s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, et al. Cancer care coordination: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 30 years of empirical studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):532–546. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9876-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health, The NHS Cancer Plan. 2000. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130222181549/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4014513.pdf Accessed June6, 2019.

- 4.Wilkens J, Thulesius H, Schmidt I, et al. The 2015 national cancer program in Sweden: introducing standardized care pathways in a decentralized system. Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1378–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharpe D, Williams RN, Ubhi SS, et al. The “two-week wait” referral pathway allows prompt treatment but does not improve outcome for patients with oesophago-gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(10):977–981. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aslam MI, Chaudhri S, Singh B, et al. The “two-week wait” referral pathway is not associated with improved survival for patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Surg. 2017;43:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meechan D, Gildea C, Hollingworth L, et al. Variation in use of the 2-week referral pathway for suspected cancer: a cross-sectional analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(602):e590–7. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X654551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(Suppl S1):S92–S107. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, et al., eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; 2018. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/. Accessed June 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberstein PE, Olive KP. Pancreatic cancer: why is it so hard to treat? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(4):321–337. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13478680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenner BJ, Go VLW, Chari ST, et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: the role of industry in the development of biomarkers. Pancreas. 2017;46(10):1238–1241. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fric P, Škrha J, Šedo A, et al. Precursors of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(3):e13–e18. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J, Blackford AL, Dal Molin M, et al. Time to progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma from low-to-high tumour stages. Gut. 2015;64(11):gutjnl-2014-308653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn SJ, Choi SJ, Kim HS. Time to progression of pancreatic cancer: evaluation with multi-detector computed tomography. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48(2):164–169. doi: 10.1007/s12029-016-9876-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehrara E, Forssell-Aronsson E, Ahlman H, et al. Specific growth rate versus doubling time for quantitative characterization of tumor growth rate. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3970–3975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jooste V, Dejardin O, Bouvier V, et al. Pancreatic cancer: wait times from presentation to treatment and survival in a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(5):1073–1080. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eshuis WJ, van der Gaag NA, Rauws EAJ, et al. Therapeutic delay and survival after surgery for cancer of the pancreatic head with or without preoperative biliary drainage. Ann Surg. 2010;252(5):840–849. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd36a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokuda Y, Chinen K, Obara H, et al. Intervals between symptom onset and clinical presentation in cancer patients. Intern Med. 2009;48(11):899–905. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawford SC, Davis JA, Siddiqui NA, et al. The waiting time paradox: population based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poruk KE, Firpo MA, Adler DG, et al. Screening for pancreatic cancer: why, how, and who? Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):17–26. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825ffbfb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz S, Campbell UB, Gatto NM, et al. Toward a clarification of the taxonomy of “bias” in epidemiology textbooks. Epidemiology. 2015;26(2):216–222. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):488–495. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitter JG, Lukács G, Csanádi M, et al. Clinical impact of treatment delay in pancreatic cancer patients revisited. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(12):2621–2622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.University of York. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York, Centre for Reviews & Dissemination; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjeevi S, Ivanics T, Lundell L, et al. Impact of delay between imaging and treatment in patients with potentially curable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103(3):267–275. doi: 10.1002/bjs.2016.103.issue-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikou GC, Tsatali E, Th A,et al. The significance of the early detection of clinical symptoms in the overall survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. Ann Gastroenterol. 2001;14(1):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swords DS, Mone MC, Zhang C, et al. Initial misdiagnosis of proximal pancreatic adenocarcinoma is associated with delay in diagnosis and advanced stage at presentation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(10):1813–1821. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2923-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gobbi PG, Bergonzi M, Comelli M, et al. The prognostic role of time to diagnosis and presenting symptoms in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amr B, Shahtahmassebi G, Briggs CD, et al. Assessment of the effect of interval from presentation to surgery on outcome in patients with peri-ampullary malignancy. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18(4):354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy GM, Redmond CE, Murphy S, et al. Preoperative CT in patients with surgically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: does the time interval between CT and surgery affect survival? Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(3):620–628. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1254-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raptis DA, Fessas C, Belasyse-Smith P, et al. Clinical presentation and waiting time targets do not affect prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Surgeon. 2010;8(5):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean SR, KARSANJI D, WILSON J, et al. The effect of wait times on oncological outcomes from periampullary adenocarcinomas. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(8):853–858. doi: 10.1002/jso.23338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchegiani G, Andrianello S, Perri G, et al. Does the surgical waiting list affect pathological and survival outcome in resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma? HPB. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yun YH, Kim YA, Min YH, et al. The influence of hospital volume and surgical treatment delay on long-term survival after cancer surgery. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(10):2731–2737. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deriban G, Andreevski B, Mishevski J, et al. Obstructive jaundice caused by pancreatic head malignancies are there predictive factors for successful endoscopic biliary stenting? Prilozi. 2012;33(2):59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghadimi BM, Horstmann O, Jacobsen K, et al. Delay of diagnosis in pancreatic cancer due to suspected symptomatic cholelithiasis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(12):1437–1439. doi: 10.1080/003655202762671323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Driedger MR, Dixon E, Mohamed R, et al. The diagnostic pathway for solid pancreatic neoplasms: are we applying too many tests? J Surg Res. 2015;199(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glant JA, Waters JA, House MG, et al. Does the interval from imaging to operation affect the rate of unanticipated metastasis encountered during operation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma? Surgery. 2011;150(4):607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raman SP, Reddy S, Weiss MJ, et al. Impact of the time interval between MDCT imaging and surgery on the accuracy of identifying metastatic disease in patients with pancreatic cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(1):W37–W42. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mangel L, Tornóczky T, Zemplényi A, et al. Az első onkológiai ellátás időfaktorának szerepe a daganatos betegségek túlélési mutatóiban. Irodalmi áttekintés. Orv Hetil. 2018;159(14):535–546. doi: 10.1556/650.2018.30920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deshwar AB, Sugar E, Torto D, et al. Diagnostic intervals and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) resectability: a single-center retrospective analysis. Ann Pancreat Cancer. 2018;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka S, Kinjo Y, Kataoka Y, et al. Statistical issues and recommendations for noninferiority trials in oncology: a systematic review. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(7):1837–1847. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.European Medicines Agency. ICH Topic E9. Statistical principles for clinical trials. 1998. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002928.pdf, Accessed June6, 2019.

- 48.Institute for Healthcare Improvement, IHI triple aim initiative. 2017. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed June6, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Department of Health, The NHS Cancer Plan. 2000. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130222181549/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4014513.pdf Accessed June6, 2019.