Abstract

Background: Improving the maternal health is one of the world’s most challenging problems. Despite significant movements over the past decades, maternal health has been still considered as a central goal for sustainable development. Maternal near miss (MNM) cases experience long-term physical and psychological effects. To present a clear portrait of the current situation, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis with the purpose to assess the worldwide prevalence of MNM.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review on PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases to find published papers in English, before March 2019 and regardless of the type of study. We, then, assessed the prevalence of MNM according to the World Health Organization(WHO) criteria. Finally, 49 papers were included in the study. Random effects meta-analysis was used to pool the available prevalence. The quality of studies was also evaluated.

Results: The weighted pooled worldwide prevalence of MNM, was 18.67/1000 (95% CI: 16.28-21.06). Heterogeneity was explored using subgroup analyses based on the continent and the country. We used meta-regression of MNM on MD which resulted in adjusted R-squared as78.88%.

Conclusion: The prevalence of MNM was considerable. Low- and middle-income countries should develop systematic approaches to improve quality of care in the facilities and to reducethe risk of MNM events, with the hope to women’s health.

Keywords: Maternal near miss, Maternal health, Prevalence, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

In the way of reaching Millennium Development Goals to end preventable maternal mortality, it is still regarded as an unfinished agenda and one of the world’s most challenging problems. Despite significant movements over the past years, it still continued to be as an open discussion in the post-2015 framework for sustainable development targets and investment priority.1 According to the perspective of World Health Organization (WHO), every pregnant woman and newborn should receive quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal periods.1 Although there was a 45% decrease in the worldwide maternal deaths (MD) since 1990, there are still 800 deaths per day from highly preventable causes before, during, and after the time of childbirth.1

In 2004, WHO published a manual under the title “Beyond the Numbers: reviewing maternal death and complications to make pregnancy safer”,that emphasizes the need for going beyond merely counting deaths to developing an understanding of why they happen and how they can be prevented.2 In recent years the term “near miss” emerged in the lexicon of maternal health for the evaluation of the quality of obstetric care.2 In April 2009, a paper published by the WHO working group defined maternal near miss (MNM) as “a woman who nearly died but survived a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days after childbirth”.3 In other word, a woman is considered a near miss case if she survives a life-threatening condition (i.e. organ dysfunction).3 Accordingly, prevalence of near-miss, MNM, started to gradually find its way as a useful measurement for the evaluation of safe motherhood programs in populations.2

Then, health professionals and administrators have used MNM to evaluate the facilities for maternal care to reduce the fatality among women with near miss complications and to provide a basis on which further researches are conducted.2 Based on WHO criteria MNM ratio (MNMR) mentions to the number of maternal near-miss cases per 1000 live births (LB).3 This criterion is being reviewed to improve the quality of care, because a large number of MNM cases will experience long-term physical and psychological effects.3 That due to the lack of accurate statistics of psychological complications and burden of disease, implementation of supportive care, screening of traumatic childbirth, and early counseling prior to the beginning of post-traumatic stress or depression was suggested.4,5 But at present, studies that have examined the global MNM rate are very low or old6,7 and according to WHO criteria, accurate statistics are not available from these mothers. Considering this gap and need for aggregated information for policy and decision making on reducing maternal morbidity and mortalities, the purpose of this study is to systematically review worldwide prevalence of MNM.

Material and Methods

Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist,8 this study was designed to review the body of the available literature on MNM published until March 2019. We have searched the electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science and manually checked references of the identified relevant papers. Regarding eligibility criteria and regardless of the type of study, we include articles that have identified mothers according to WHO criteria (Including renal, cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, coagulation/hematological, uterine dysfunction and neurological) 3 as well as articles that extract the number of MD and the number of live births. We excluded studies targeted certain groups or conditions such as some ethnic groups, twin pregnancy, post-partum hemorrhage, preeclampsia, ectopic pregnancy etc because of lack of generalizability.

We restricted the search to published articles in English language. The search strategy focused on three key words or phrases: (“maternal near miss” AND (prevalence or incidence)). The full-text articles were read to confirm eligibility and to collect relevant information from the selected abstracts. Each article was read by at least two authors independently for the reading and synthesis stages. The disagreements between them were solved by consensus. The reasons for exclusion criteria were listed in the PRISMA flowchart.

The information of studies include author, year, country, continent , design of study, sample size, MNM, MD, MNMR and quality score were collected in prepared a separate page and are summarized in Table 1.9-57 Quality of the studies was evaluated according to the set of criteria based on Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance on conducting prevalence and incidence reviews.58 The quality of a paper was assessed based on criteria such as the appropriate recruitment of the participants, the representativeness of the sample, the sufficiency of the coverage of the identified sample by the data analysis, the adequacy of the sample size, the objectivity and standard of the criteria used for measurement of the condition, the detailed description of the participants and the setting, the reliability of the condition measurement, the adequacy of the response rate the appropriateness of the statistical analysis, and the appropriate coping with the low response rate, in case it existed. All the article met the high-quality standard. When the indicators were not mentioned, but contained the necessary information for its calculation, it was assessed and added to the results in the review. Among the results, the following quantitative indicators were extracted.

Table 1. Specifications of studies about prevalence Maternal Near Miss based on the WHO approach in world .

| Author | Year | Country | Continent | Design | Sample (LB) | MNM | MD | MNM/1000 | JBI Score |

| Souza9 | 2012 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 82 388 | 770 | 140 | 9/34 | 17 |

| Jabir10 | 2013 | Iraq | Asia | Cross-sectional | 25 472 | 129 | 16 | 5/06 | 16 |

| Nelissen11 | 2013 | Tanzania | Africa | Cross-sectional | 9152 | 216 | 32 | 23/6 | 17 |

| Ps12 | 2013 | India | Asia | Cross-sectional | 7390 | 131 | 17/80 | 18 | |

| Rana13 | 2013 | Nepal | Asia | Cohort | 41 676 | 157 | 3/80 | 15 | |

| Tunçalp14 | 2013 | Ghana | Africa | Cohort | 3438 | 94 | 37 | 28/60 | 17 |

| Setia15 | 2013 | Indonesia | Asia | Cross-sectional | 14 559 | 341 | 23/42 | 16 | |

| Dias16 | 2014 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 2 300 000 | 10/21 | 16 | ||

| Galvão17 | 2014 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 16243 | 77 | 17 | 5/80 | 15 |

| Luexay18 | 2014 | Laos | Asia | Cohort | 1215 | 11 | 2 | 9/80 | 15 |

| Pandey19 | 2014 | India | Asia | Case-control | 5273 | 633 | 247 | 120/04 | 14 |

| Tahira20 | 2014 | Pakistan | Asia | Cross-sectional | 1000 | 67 | 67 | 17 | |

| Bakshi21 | 2015 | India | Asia | Cross-sectional | 688 | 51 | 10 | 5/12 | 18 |

| Bashour22 | 2015 | Egypt* | Africa | Cross-sectional | 9063 | 71 | 6 | 7/83 | 17 |

| Madeiro23 | 2015 | Brazil | South America | Cohort | 5841 | 56 | 10 | 9/60 | 18 |

| Mazhar24 | 2015 | Pakistan | Asia | Cross-sectional | 13 175 | 94 | 38 | 7/13 | 15 |

| Menezes25 | 2015 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 20 435 | 77 | 17 | 3/76 | 16 |

| Oliveira26 | 2015 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 2055 | . | 12/8 | 17 | |

| Rulisa27 | 2015 | Rwanda | Africa | Cross-sectional | 1739 | 13 | 8 | 14 | |

| Tan28 | 2015 | China | Asia | Cross-sectional | 34 547 | 8 | 5 | 2/3 | 15 |

| Abha29 | 2016 | India | Asia | Cohort | 13 895 | 211 | 102 | 15/18 | 17 |

| Cecatti20 | 2016 | Brazil | South America | Cross-sectional | 82 388 | 770 | 140 | 9/34 | 17 |

| De Mucio31 | 2016 | Latin America | South America | Cross-sectional | 3196 | 37 | 12/3 | 16 | |

| Ghazivakili32 | 2016 | Iran | Asia | Cross-sectional | 38 663 | 192 | 7 | 4/97 | 16 |

| Kalisa33 | 2016 | Rwanda | Africa | Cohort | 3994 | 86 | 13 | 21/51 | 16 |

| Mohammadi34 | 2016 | Iran | Asia | Case-control | 12 965 | 82 | 12 | 6/30 | 15 |

| Nakimuli35 | 2016 | Uganda | Africa | Cohort | 25 840 | 695 | 130 | 8/42 | 15 |

| Nansubuga36 | 2016 | Uganda | Africa | Cross-sectional | 1557 | 434 | 287/70 | 18 | |

| Norhayati37 | 2016 | Malaysia | Asia | Cross-sectional | 21 579 | 395 | 2 | 2/20 | 15 |

| Oladapo38 | 2016 | Nigeria | Africa | Cross-sectional | 91 724 | 1451 | 998 | 15/81 | 16 |

| O'Malley39 | 2016 | Ireland | Europe | Cross-sectional | 4502 | 16 | 0 | 3/55 | 17 |

| Parmar40 | 2016 | India | Asia | Cross-sectional | 1929 | 46 | 18 | 23/85 | 18 |

| Rathod41 | 2016 | India | Asia | Cohort | 21 992 | 161 | 66 | 7/56 | 17 |

| Ray42 | 2016 | India | Asia | Cross-sectional | 4800 | 220 | 17 | 45/83 | 16 |

| Tanimia43 | 2016 | Papua New Guinea | Oceania | Cross-sectional | 13 338 | 122 | 9 | 9/1 | 16 |

| Witteveen44 | 2016 | Netherlands | Europe | Cross-sectional | 371 623 | 1179 | 3/17 | 15 | |

| Bolnga45 | 2017 | Papua New Guinea | Oceania | Cohort | 6019 | 153 | 10 | 25/4 | 16 |

| Chandak46 | 2017 | India | Asia | Cross-sectional | 13 186 | 137 | 10/38 | 16 | |

| Goldenberg47 | 2017 | Zambia** | Africa | Cross-sectional | 122 707 | 4866 | 39/65 | 15 | |

| Liyew48 | 2017 | Ethiopia | Africa | Cross-sectional | 29 697 | 238 | 8/01 | 15 | |

| Mbachu49 | 2017 | Nigeria | Africa | Cross-sectional | 262 | 52 | 5 | 198 | 15 |

| Serruya50 | 2017 | Latin America | South America | Cross-sectional | 712 081 | 21985 | 1028 | 31/50 | 16 |

| Awowole51 | 2018 | Nigeria | Africa | Case-control | 11 242 | . | 3/8 | 15 | |

| Chikadaya52 | 2018 | Zimbabwe | Africa | Cohort | 11 871 | 110 | 13 | 9/3 | 16 |

| Iwuh53 | 2018 | South Africa | Africa | Case-control | 19 222 | 112 | 13 | 5/83 | 17 |

| Oppong54 | 2018 | Ghana | Africa | Cross-sectional | 8433 | 288 | 62 | 34/2 | 17 |

| Woldeyes55 | 2018 | Ethiopia | Africa | Cross-sectional | 2737 | 138 | 24 | 50/42 | 16 |

| Yang56 | 2018 | China | Asia | Cohort | 14 014 | 265 | 18/90 | 17 | |

| Deepti Gupta57 | 2018 | India | Asia | Cohort | 4533 | 74 | 15 | 16/32 | 16 |

To explore MNM ratio with WHO approach, the number of cases in a thousand LB was considered.3 We applied a random effects meta-analysis to obtain the weighted average prevalence with 95% CIs for studies. Heterogeneity was estimated using the Cochran I2 statistic and its P value.59 Subgroup analysis was accomplished to analyze MNM as WHO criteria. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1(Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

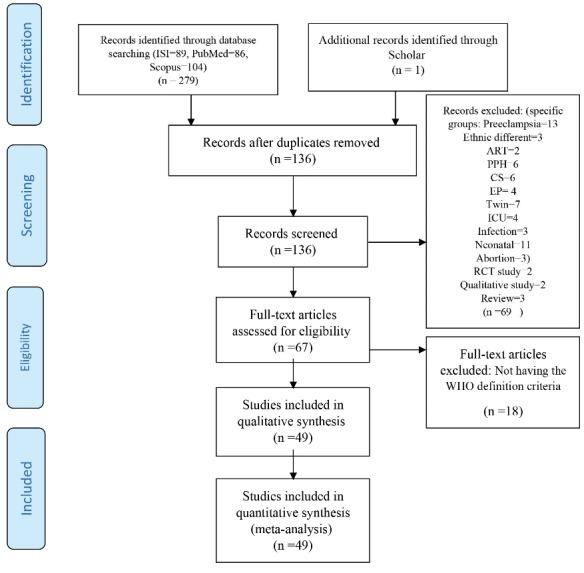

The primary search recognized 300 published papers, including 86 in PubMed, 89 in Web of Science and 104 in Scopus. From those, 164 articles were eliminated after removal of duplicates. Nearly 135 articles were initially screened by abstract. After excluding those who had inclusion criteria, 67 articles remained for full-text screening. Out of these 67 articles, in the next step 18 were excluded either because they had not followed the WHO definition criteria. Data have been extracted from 49 articles (Figure 1). There was well agreement (88.37%) between reviewers on the terminal articles eligible for inclusion.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the selection process of the articles.

Depending on the study design, the selected papers were cross-sectional (n = 34), cohorts (n = 12), case control (n = 3). In almost all continents, the prevalence of MNM was investigated. No studies were conducted in North America and Australia. The number of articles conducted in Asia, South America, Africa, Europe and Oceania was 20, 9, 16, 2, and 2, respectively. Most of these studies were conducted in Brazil (n = 7) and India (n = 9). Of the 34 articles, both MNM and MD were extracted; out of 15, only the prevalence of MNM was extracted. All articles were conducted since 2012, because the WHO criteria for identifying MNM was announced this year. Prevalence of MNM is reported by all the studies ranged from 2.2 to 287.7 /1000 LB.

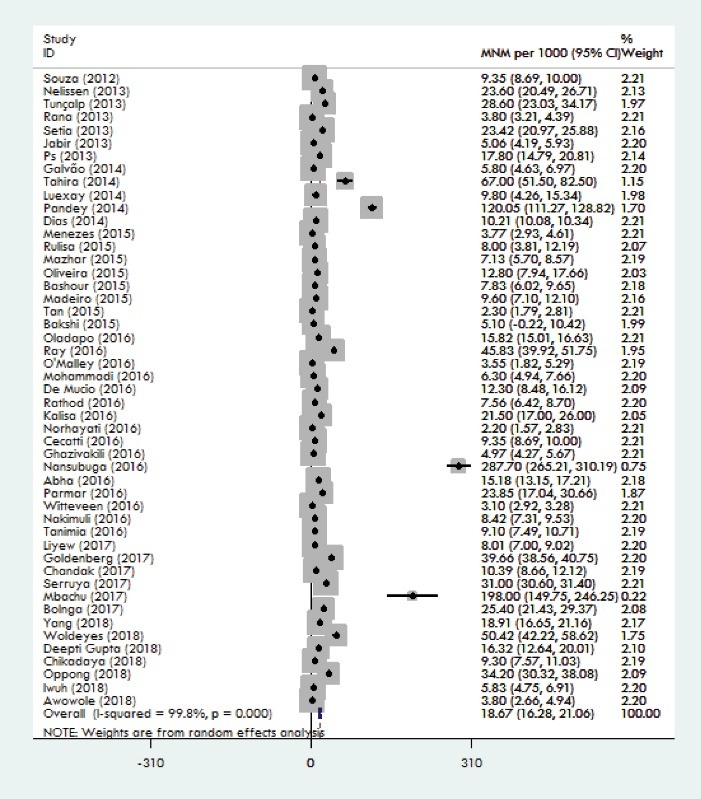

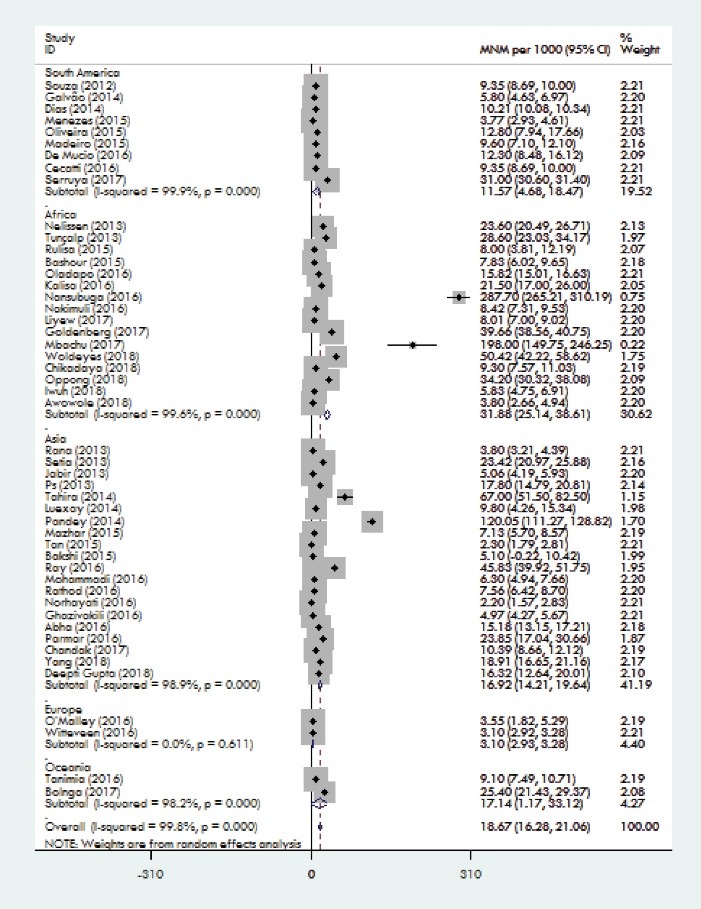

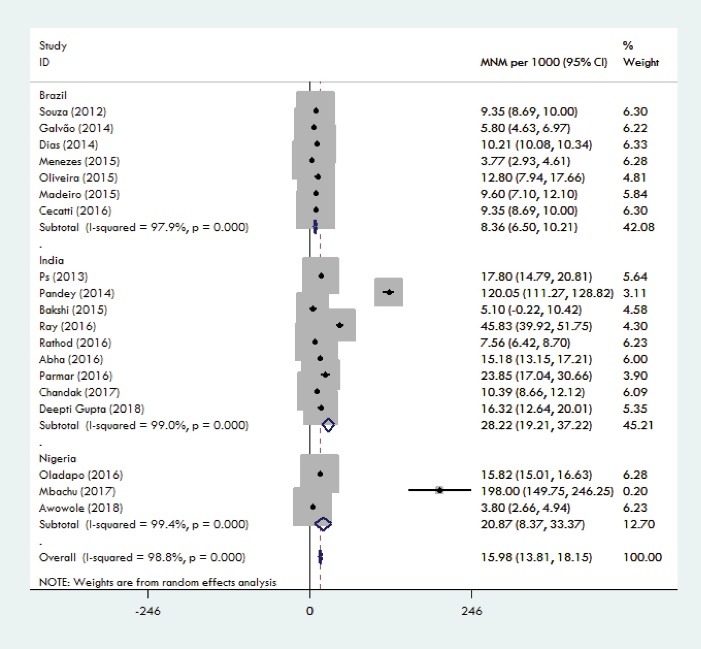

The weighted pooled worldwide prevalence of MNM, was 18.67/1000 (95% CI: 16.28-21.06). There was a large volume of heterogeneity in the prevalence of MNM (I2 = 99.8%; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.0001; Figure 2). The subgroup analysis will help to explore heterogeneity in the MNM prevalence. Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the continent and the country. Because maternal health indicators are very diverse in countries and continents. By continents, MNM prevalence ranged from 3.10/1000 in the Europe to 31.88/1000 LB in the Africa. Among the studies that had been conducted in Asia, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 16.92 (95% CI: 14.21-19.64) with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2= 98.9%; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001).Among the studies that had been conducted in South America, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 11.57 (95% CI: 4.68-18.47) with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 99.9%; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001).Among the studies that had been conducted in Africa, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 31.88 [95% CI: 25.14-38.61] with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 99.6%; Cochran Q-statistic P = 0.00). Among the studies that had been conducted in Europe, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 3.10 (95% CI: 2.93-3.28) with non-significant little heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0.0%; Cochran Q-statistic P = 0.61). Among the studies that had been conducted in Oceania, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 17.14 (95% CI: 1.17-33.12) with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 98.2%; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001; Figure 3). For heterogeneous justification, a subgroup analysis was also conducted based on the country; for example, the prevalence of MNM in Brazil was 8.36 (95% CI: 6.50-10.21) with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 97.9%; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001). Among the studies that had been conducted in India, weighted pooled prevalence of MNM was 28.22 [95% CI: 19.21-37.22] with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 99 %; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001) and in the Nigeria was 20.87 [95% CI: 8.37-33.37] with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 99.4 %; Cochran Q-statistic P < 0.001; Figure 4). The results indicate that the heterogeneity between studies is significant in a country (Including Brazil, India and Nigeria).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the pooling of overall worldwide prevalence of MNM.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the pooling of overall continents prevalence of MNM.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the pooling of overall countries prevalence of MNM.

To further assess the source of heterogeneity we used meta-regression of MNM on MD which resulted in adjusted R-squared as 78.88%. This means that much of the observed heterogeneity among studies could be explained by maternal death as Pearson correlation coefficient between MNM and MD among included studies was also 70.16% (P < 0.001). The coefficient of meta-regression shows that for each unit increase in MD (per 100 000) the average of MDM (per 1000) is expected to increase by 0.024. This implies that in order to reduce the risk of MNM events, it’s helpful to work on the risk factors on MD. The weighted pooled worldwide prevalence of MD among 35 studies that had reported it, was 294.75/100 000 LB [95% CI: 244.06-345.44]. A sensitivity analysis using metainf command which was performed to see whether the total result is affected by any individual studies showed that some studies had some impact on the total result but this impact was not statistically significant. Publication bias was assessed visually and statistically using funnel plot and Egger’s and Begg’s test. Regarding the asymmetry shape of the funnel plot and the P values of Egger’s and Begg’s test that were 0.160 and 0.000 respectively, it seems that there could be some sort of publication bias. However, the results tended to be unchanged after applying Trim and Fill approach.

Discussion

We found that more than 18.67/1000 LB of the general population of the world suffered from MNM based on WHO criteria. So far, two systematic review in 20046 and 20117 have been conducted to determine the prevalence of maternal mortality globally. In recent years, a review study conducted to determine the death of mothers based on WHO criteria, has not been carried out. Therefore, comparing the prevalence’s changes during the passage of time is relatively difficult. In a review conducted by Say et al, prevalence’s of MNM ranged from 0.80% to 8.23% in studies which had disease-specific criteria while it was from 0.38% to1.09% in studies which had organ-system based criteria and it was from 0.01% to 2.99% in studies which had management-based criteria.6

In another review conducted by Tunçalp et al, the prevalence’s varied between 0.6 and 14.98% in studies which had disease specific criteria while it varied between 0.14% and 0.92% in studies which had Mantel (organ dysfunction) criteria and it varied between 0.04% and 4.54% in studies which had management-based criteria. A meta-analysis in the aforementioned study, estimated that MNM was 0.42% (95% CI 0.40-0.44%) for the Mantel (organ dysfunction) criteria.7 In both of these studies, the reported MNM prevalence is in 100 live birth, but in our study, according to the WHO definition, the number of MNM reported in 1000 live births, Which indicates that the MNM rate has declined in general, and the WHO’s unit case-identification criteria of MNM and its declare to all countries has played a major role in improving quality care.

Other results of our study were exploring the MNM prevalence in countries. In our study the prevalence of MNM according to the WHO criteria in Brazil was 8.36/1000, which is consistent with the systematic review of da Silva et al in Brazil (the MNMR varied from 4.4/1000 LB).60 The reason for the little statistical difference is the difference in the years of the study as well as various definitions in identifying the cases of maternal death. In the present study the MNM prevalence in middle and low income countries of Asia and Africa to compare to high-income countries, are higher; which is in line with the study of Tunçalp et al.7 Of course, in these continents, countries such as Iran have a MNM prevalence (1/1000 LB) similar to that of European countries.61 The meta-regression between MNM and MD justifies the heterogeneity of studies in countries, because even in one country, there is variation in the factors like the quality of care which are major determinant for both MD and MNM. In fact, the high correlation between MNM and MD is because of possible common risk factors.

The limitation of this study is the selection of articles based on WHO criteria that led to automatically deletion of the articles published before 2012. Despite this limitation, the study has a number of strengths. First, it is the first worldwide systematic review of the prevalence of MNM conducted according to WHO criteriathat we examined study quality, publication bias and sensitivity analysis. Secondly, the number of articles that have been Meta-analyzes is high and reflects a comprehensive view of the health of mothers.

Conclusion

The prevalence of MNM is considerable in many countries, especially in low- and middle-income countries. An important finding of this study was, the significant and direct relationship between MNM and maternal death. This means that fluctuations in one lead to another change. Therefore, the maternal mortality index can be considered as the most reliable indicator in the assessment of maternal health. Based on this index, countries should establish a national health care system for increase standard and safety practices of health providers. It is recommended that, in view of the fact that improving maternal health is one of the goals of sustainable development by 2030, similar studies will be undertaken in the future to investigate the trend of MNM rate in order to plan the necessary program and make the appropriate policies.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public.

Authors’ contributions

TK and SA designed the research, conducted systematic research, extracted data and wrote the manuscript. HHM and SA analyzed data. All authors had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their deepest thanks to all librarians who helped them to access information resources in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Citation: Abdollahpour S, Heidarian Miri H, Khadivzadeh T. The global prevalence of maternal near miss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9(4):255-262. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2019.35.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Maternal mortality fact sheet No. 348. Geneva: WHO; 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112318/1/WHO_RHR_14.06_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 5 February 2018.

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Beyond the numbers: Reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications: the WHO near-miss approach for maternal health. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

- 4.Abdollahpour S, Keramat A, Mousavi SA, Khosravi A, Motaghi Z. The effect of debriefing and brief cognitive-behavioral therapy on postpartum depression in traumatic childbirth: a randomized clinical trial. J Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2018;6(1):1122–31. doi: 10.22038/jmrh.2017.10000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdollahpour S, Khosravi A, Motaghi Z, Keramat A, Mousavi SA. Effect of brief cognitive behavioral counseling and debriefing on the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder in traumatic birth: a randomized clinical trial. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(7):1173–8. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Say L, Pattinson RC, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss) Reprod Health. 2004;1(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunçalp O, Hindin MJ, Souza JP, Chou D, Say L. The prevalence of maternal near miss: a systematic review. BJOG. 2012;119(6):653–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souza JP, Cecatti JG, Haddad SM, Parpinelli MA, Costa ML, Katz L. et al. The WHO maternal near-miss approach and the maternal severity index model (MSI): tools for assessing the management of severe maternal morbidity. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e44129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabir M, Abdul-Salam I, Suheil DM, Al-Hilli W, Abul-Hassan S, Al-Zuheiri A. et al. Maternal near miss and quality of maternal health care in Baghdad, Iraq. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelissen EJ, Mduma E, Ersdal HL, Evjen-Olsen B, van Roosmalen JJ, Stekelenburg J. Maternal near miss and mortality in a rural referral hospital in northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ps R, Verma S, Rai L, Kumar P, Pai MV, Shetty J. “Near miss” obstetric events and maternal deaths in a tertiary care hospital: an audit. J Pregnancy. 2013;2013:393758. doi: 10.1155/2013/393758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rana A, Baral G, Dangal G. Maternal near-miss: a multicenter surveillance in Kathmandu Valley. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2013;52(190):299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunçalp O, Hindin MJ, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Adanu RM. Assessment of maternal near-miss and quality of care in a hospital-based study in Accra, Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setia S, Mutahar R, Destriatania S. Determinant of Maternal Near Miss Incidence in Indonesia (Analysis Ofsecondary Data Sdki 2007) J Ilmu Kesehat Masy. 2013;4(3):270–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dias MA, Domingues RM, Schilithz AO, Nakamura-Pereira M, Diniz CS, Brum IR. et al. Incidence of maternal near miss in hospital childbirth and postpartum: data from the Birth in Brazil study. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30 Suppl 1:S1–12. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00154213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galvão LP, Alvim-Pereira F, de Mendonça CM, Menezes FE, Góis KA, Ribeiro RF Jr. et al. The prevalence of severe maternal morbidity and near miss and associated factors in Sergipe, Northeast Brazil. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luexay P, Malinee L, Pisake L, Marie-Hélène BC. Maternal near-miss and mortality in Sayaboury Province, Lao PDR. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:945. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey A, Das V, Agarwal A, Agrawal S, Misra D, Jaiswal N. Evaluation of obstetric near miss and maternal deaths in a tertiary care hospital in north India: shifting focus from mortality to morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2014;64(6):394–9. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tahira G, Sarfraz M. Cross-sectional retrospective study on prevalence of maternal near miss in mnch department of Social Security Hospital, Islamabad. Paki J Public Health. 2014;4(4):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakshi RK, Aggarwal P, Roy D, Nautiyal R, Kakkar R. Indicators of maternal ‘near miss’ morbidity at different levels of health care in North India: a pilot study. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2015;14(3):254–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bashour H, Saad-Haddad G, DeJong J, Ramadan MC, Hassan S, Breebaart M. et al. A cross sectional study of maternal ‘near-miss’ cases in major public hospitals in Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:296. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madeiro AP, Rufino AC, Lacerda ÉZ, Brasil LG. Incidence and determinants of severe maternal morbidity: a transversal study in a referral hospital in Teresina, Piaui, Brazil. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:210. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0648-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazhar SB, Batool A, Emanuel A, Khan AT, Bhutta S. Severe maternal outcomes and their predictors among Pakistani women in the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;129(1):30–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menezes FE, Galvão LP, de Mendonça CM, Góis KA, Ribeiro RF Jr, Santos VS. et al. Similarities and differences between WHO criteria and two other approaches for maternal near miss diagnosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(11):1501–6. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira LC, da Costa AA. Maternal near miss in the intensive care unit: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2015;27(3):220–7. doi: 10.5935/0103-507x.20150033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rulisa S, Umuziranenge I, Small M, van Roosmalen J. Maternal near miss and mortality in a tertiary care hospital in Rwanda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:203. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan J, Liu XH, Yu C, Chen M, Chen XF, Sun X. et al. Effects of medical co-morbidities on severe maternal morbidities in China: a multicenter clinic register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(8):861–8. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abha S, Chandrashekhar S, Sonal D. Maternal near miss: a valuable contribution in maternal care. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(Suppl 1):217–22. doi: 10.1007/s13224-015-0838-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cecatti JG, Costa ML, Haddad SM, Parpinelli MA, Souza JP, Sousa MH. et al. Network for Surveillance of Severe Maternal Morbidity: a powerful national collaboration generating data on maternal health outcomes and care. BJOG. 2016;123(6):946–53. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Mucio B, Abalos E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Serruya S, Giordano D. et al. Maternal near miss and predictive ability of potentially life-threatening conditions at selected maternity hospitals in Latin America. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0250-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghazivakili Z, Lotfi R, Kabir K, Norouzi Nia R, Rajabi Naeeni M. Maternal near miss approach to evaluate quality of care in Alborz province, Iran. Midwifery. 2016;41:118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalisa R, Rulisa S, van den Akker T, van Roosmalen J. Maternal Near Miss and quality of care in a rural Rwandan hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):324. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1119-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammadi S, Essén B, Fallahian M, Taheripanah R, Saleh Gargari S, Källestål C. Maternal near-miss at university hospitals with cesarean overuse: an incident case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(7):777–86. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakimuli A, Nakubulwa S, Kakaire O, Osinde MO, Mbalinda SN, Nabirye RC. et al. Maternal near misses from two referral hospitals in Uganda: a prospective cohort study on incidence, determinants and prognostic factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:24. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0811-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nansubuga E, Ayiga N, Moyer CA. Prevalence of maternal near miss and community-based risk factors in Central Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135(2):214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norhayati MN, Nik Hazlina NH, Sulaiman Z, Azman MY. Severe maternal morbidity and near misses in tertiary hospitals, Kelantan, Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:229. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oladapo OT, Adetoro OO, Ekele BA, Chama C, Etuk SJ, Aboyeji AP. et al. When getting there is not enough: a nationwide cross-sectional study of 998 maternal deaths and 1451 near-misses in public tertiary hospitals in a low-income country. BJOG. 2016;123(6):928–38. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Malley EG, Popivanov P, Fergus A, Tan T, Byrne B. Maternal near miss: what lies beneath? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parmar NT, Parmar AG, Mazumdar VS. Incidence of Maternal “Near-Miss” Events in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Central Gujarat, India. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(Suppl 1):315–20. doi: 10.1007/s13224-016-0901-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rathod AD, Chavan RP, Bhagat V, Pajai S, Padmawar A, Thool P. Analysis of near-miss and maternal mortality at tertiary referral centre of rural India. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(Suppl 1):295–300. doi: 10.1007/s13224-016-0902-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray N, Patil SK, Kshirsagar NS, Patil Y, Laddad M. Maternal near miss in a tertiary care hospital: a cross sectional study. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2016;5(51):3352–4. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2016/755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanimia H, Jayaratnam S, Mola GL, Amoa AB, de Costa C. Near-misses at the Port Moresby General Hospital: a descriptive study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56(2):148–53. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witteveen T, de Koning I, Bezstarosti H, van den Akker T, van Roosmalen J, Bloemenkamp KW. Validating the WHO Maternal Near Miss Tool in a high-income country. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(1):106–11. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolnga JW, Morris M, Totona C, Laman M. Maternal near-misses at a provincial hospital in Papua New Guinea: A prospective observational study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(6):624–9. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chandak PO, Kedar KV. Maternal near miss- a review from tertiary care hospital. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2017;6(47):3633–7. doi: 10.14260/Jemds/2017/783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldenberg RL, Saleem S, Ali S, Moore JL, Lokangako A, Tshefu A. et al. Maternal near miss in low-resource areas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(3):347–55. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liyew EF, Yalew AW, Afework MF, Essén B. Incidence and causes of maternal near-miss in selected hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mbachu II, Ezeama C, Osuagwu K, Umeononihu OS, Obiannika C, Ezeama N. A cross sectional study of maternal near miss and mortality at a rural tertiary centre in southern Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1436-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serruya SJ, de Mucio B, Martinez G, Mainero L, de Francisco A, Say L. et al. Exploring the concept of degrees of maternal morbidity as a tool for surveillance of maternal health in Latin American and Caribbean settings. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8271042. doi: 10.1155/2017/8271042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Awowole IO, Omitinde OS, Arogundade FA, Bola-Oyebamiji SB, Adeniyi OA. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury requiring dialysis as an indicator of severe adverse maternal morbidity at a tertiary center in Southwest Nigeria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;225:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chikadaya H, Madziyire MG, Munjanja SP. Incidence of maternal near miss in the public health sector of Harare, Zimbabwe: a prospective descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):458. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwuh IA, Fawcus S, Schoeman L. Maternal near-miss audit in the Metro West maternity service, Cape Town, South Africa: a retrospective observational study. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(3):171–5. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oppong SA, Bakari A, Bell AJ, Bockarie Y, Adu JA, Turpin CA. et al. Incidence, causes and correlates of maternal near-miss morbidity: a multi-centre cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2019;126(6):755–62. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woldeyes WS, Asefa D, Muleta G. Incidence and determinants of severe maternal outcome in Jimma University teaching hospital, south-West Ethiopia: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang YY, Fang YH, Wang X, Zhang Y, Liu XJ, Yin ZZ. A retrospective cohort study of risk factors and pregnancy outcomes in 14,014 Chinese pregnant women. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(33):e11748. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000011748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deepti Gupta NA, Noor N, Joshi T, Bhargava M. Incidence of maternal near miss and mortality cases in central India tertiary care centre and evaluation of various causes. The New Indian Journal of OBGYN. 2018;4(4):112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.da Silva JM, Fonseca SC, Dias MAB, Izzo AS, Teixeira GP, Belfort PP. Concepts, prevalence and characteristics of severe maternal morbidity and near miss in Brazil: a systematic review. Rev Bras Saúde Mater Infant. 2018;18(1):7–35. doi: 10.1590/1806-93042018000100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abdollahpour S, Miri HH, Khadivzadeh T. The maternal near miss incidence ratio with WHO approach in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24(3):159–66. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_165_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]