Abstract

Objectives

We explored the short-term impact of pesticide exposure on asthma exacerbation among children with asthma in an agricultural community.

Methods

We obtained repeated urine samples from a subset of 16 school-age children with asthma (n = 139 samples) as part of the Aggravating Factors of Asthma in a Rural Environment (AFARE) study cohort. Biomarkers of organophosphate (OP) pesticide exposure (dialkylphosphates (DAPs)), and asthma exacerbation (leukotriene E4 (uLTE4)) were assessed in urine samples. We used generalized estimating equations to examine the association of summed measures of creatinine-adjusted DAPs (total dimethyl alkylphosphate (EDM), total diethyl alkylphosphate (EDE), and total dialkylphosphate pesticides (EDAP)) and uLTE4 concentration, adjusting for multiple confounders, yielding beta-coefficients with 95% CIs.

Results

A total of 139 observations were obtained from the 16 children over the study period, the total number of samples per subject ranged from 1 to 12 (median: 10.5). The geometric mean (GM) of creatinine-adjusted EDE, EDM and EDAP in this population were 81.0, 71.8 and 168.0 nmol/g respectively. Increase in uLTE4 levels was consistently associated with increased exposures to DAPs (interquartile range in μg/g): βEDE: 8.7 (95%CI: 2.8, 14.6); βEDM: 1.1 (0.5, 1.7); βEDAP: 4.1 (0.7, 7.5).

Conclusion

This study suggests that short-term OP exposure is associated with a higher risk of asthma morbidity, as indicated by increased uLTE4 levels in this cohort of children with asthma in an agricultural community. Additional studies are required to confirm these adverse effects, and explore the mechanisms underlying this relationship.

Keywords: Organophosphate pesticides, Pediatric Asthma, Biomarkers

Introduction

Pediatric asthma affects an estimated 8.3% of children in the United States and is often complicated by acute exacerbation episodes.1 These exacerbations account for over 700,000 childhood emergency department (ED) visits annually, with almost 5% of children with asthma requiring hospitalization.1,2

Environmental pollutants are established risk factors for asthma exacerbation;3,4 the effects of these exposures have been extensively studied, particularly in urban and inner-city asthma populations.5 Though asthma prevalence in rural communities in the United States is comparable to urban communities,6 the effects of these exposures on exacerbation among children living in rural and agricultural areas have received less attention because of apparent poorer air quality in urban areas.4 However, pollutant sources in rural/agricultural communities tend to differ from sources in inner-city/urban communities;6,7 agricultural communities may have fewer urban pollution sources (e.g., motor vehicle traffic and industrial emissions), but have substantially more local sources like pollen and similar aeroallergens, emissions from industrial-scale agricultural operations including windblown dust, animal agricultural emissions, and pesticide drift from large crop-growing operations.8

Organophosphate pesticides (OPs) are widely used in crop production, and exposure levels among children in agricultural communities exceed their non-agricultural counterparts.9 OP exposure levels may reflect off-target drift, parent take-home exposure, and exposure through consumption of local food crops.10 OPs, particularly at high acute doses, result in acetylcholinesterase (AChE) dysfunction11 and can affect respiratory function with resulting airway hyperreactivity and inflammation.11,12 Low level, chronic exposures may also affect respiratory conditions.13,14

Several studies have explored the relationship between exposure to OPs and adverse respiratory health outcomes including asthma;15-17 the few studies investigating these relationships among children have been based on self-reported exposure metrics18,19 and early-life exposures.20,21 However, characterization of short-term exposures among children with asthma and potential exacerbation has been lacking.

We describe results of a longitudinal study of children with asthma who reside in an agricultural region of Washington State characterized by extensive organophosphate insecticide use. This well-defined cohort of children provides a unique opportunity to characterize longitudinal variation in exposure to OPs using well established metabolite biomarkers alongside an emerging biomarker of asthma exacerbation, urinary leukotriene (uLTE4). Noninvasive measurement of uLTE4 has been validated as a marker of systemic cysteinyl leukotriene activity, and an indirect marker of lung cysteinyl leukotriene activity (a lipid mediator known to play a central pathophysiological role in asthma).22,23 The primary objective of our investigation was to describe the association between short-term variations in OP exposure and this measure of asthma exacerbation among children with asthma.

Methods

Study population

The Aggravating Factors of Asthma in a Rural Environment (AFARE) project was conducted in the Yakima Valley, an agricultural region of Washington State characterized by a high density of fruit crops, vegetables, and large dairy operations. Pesticides commonly used in the region include OPs such as phosmet, diazinon, malathion, and chlorpyrifos.24,25

Details about recruitment and baseline health evaluations for AFARE have been reported previously.26 Briefly, the study involved collection of longitudinal data to explore and identify environmental factors that exacerbate pediatric asthma in rural settings. The children were of school age (between the ages of 6 and 16 years) at baseline and had no serious illnesses other than asthma. For this analysis, we used the repeated measures made on a subset of children for which urine specimens were collected in the AFARE cohort (n = 16), at 6-day intervals over a 4-month period (July 2012 to October 2012). These participants were chosen based on residential proximity to home-based air monitors used in the main study, as urine samples were collected during trips to attend to monitors.

Outcome assessment

Urinary leukotriene E4 monitoring

Urinary leukotriene E4 (uLTE4) was used to assess acute inflammation among children with asthma. Urinary LTE4 level was measured from a spot urine sample, scheduled to be collected from each child every 6 days during the study period. After collection, samples were stored at −20°C. Quantitative analysis of uLTE4 was performed in the University of Washington Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Studies Functional Genomics Laboratory using the Cayman Human Leukotriene E4 EIA Kit (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Urinary creatinine concentration was measured for each sample to account for urine dilution. Creatinine analysis was conducted by the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the University of Washington. Creatinine-adjusted concentrations were used for final model analyses.

Assessment of pesticide exposure

Organophosphate pesticide monitoring

Dialkylphosphates in urine result from the degradation of organophosphate pesticides and primarily reflect a recent exposure; OP pesticides are quickly metabolized and excreted, with average half-lives of about 48 hours.27 Spot urine samples were analyzed for organophosphates at the same time uLTE4 was assessed. Six urinary DAP metabolites were measured in participants’ urine; dimethylphosphate (DMP), dimethylthiophosphate (DMTP), dimethyldithiophosphate (DMDTP), diethylphosphate (DEP), diethylthiophosphate (DETP), and diethyldithiophosphate (DEDTP). Metabolite reporting limits were based on the limit of detection (LOD) for each DAP compound, and masses below the limit of detection were approximated as LOD/√2. Urinary creatinine concentration was measured to account for urine dilution.

To provide an indicator of total exposure to OPs, we used summative measures of DAPs for evaluation of associations with the outcome, rather than measures of individual analytes.28 Summed measures account for circumstances where individual OP pesticides devolve to more than one DAP metabolite.29 Summed DAP concentrations (total dimethyl alkylphosphate (EDM), total diethyl alkylphosphate (EDE), and total dialkylphosphate pesticides (EDAP)) were estimated by summing up molar concentrations (DAP concentration divided by their molecular weights) of metabolites. Creatinine-adjusted concentrations of EDM, EDE, and EDAP were used for final model analyses.

Covariates

Covariates in our models included potential confounders that were selected a priori based on existing evidence of relationships between the covariate and both respiratory health and ambient exposure to pesticides. Informed by previous studies, subject-specific characteristics potentially associated with asthma and asthma exacerbation were also considered: sex, age, body mass index-for-age, atopy (skin prick test positive to at least one common aeroallergen), use of inhaled corticosteroids at baseline, a measure of pulmonary inflammation collected at baseline (exhaled nitric oxide (eNO) levels), and the number of individuals in household.

Meteorological conditions have been shown to effect asthma morbidity30 and influence the potential for exposure to pesticides through various routes including an influence on exposure dose due to behavioral changes or the physiochemical properties of pesticides.31-33 To capture meteorological conditions for the week prior to uLTE4 measurements, we used data downloaded from the county weather package in R, which provides data from the national Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Historical Climatology Network on 24-hour average, maximum, and dew-point temperature, precipitation, and wind speed. We explored both forward addition and backward elimination of the covariates to fit the base models, and covariates were included in final models if they substantively influenced effect estimates (≥ 10% change in beta coefficients).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were examined, including proportions and means of sociodemographic characteristics of children in this AFARE sub-cohort, exposure to OP pesticides, and uLTE4 levels. To understand the potential exposure differential to pesticides in an agricultural population, we conducted a comparison of adjusted geometric mean levels of DAPs between children in the AFARE cohort and children of similar age participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007/2008 survey cycle (a national population-based comparison group),34 using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The 2007/2008 NHANES sample included 476 children between the age of 9 and 17 years; no sample weights were added to the NHANES data.

We evaluated associations of uLTE4 with OP metabolite concentrations using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with an exchangeable correlation matrix. The use of GEE accounts for the correlation and lack of independence of observations observed in this panel study by using quasi-likelihood methods and fairly robust variance estimators.35 Although GEE calculation of standard errors are fairly robust to the choice of correlation matrix, we explored associations using both the exchangeable (assuming all of the correlations are equal) and autoregressive (decreasing correlation for farther time periods) working correlation structures.

We fit three separate regression models for the effect of summed measures of dimethyl alkylphosphate (EDM), diethyl alkylphosphate (EDE), and all dialkylphosphate pesticides (EDAP) on uLTE4, adjusted for the set of selected confounders. In all models, the mean outcome was modeled as the linear response to the primary exposure of interest. We presented the results in models as effect sizes per interquartile range increases in exposure for comparability among the summed pesticide measures. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) for GEE analysis, and R version 3.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for exploratory and descriptive analyses.

Results

Study population

Baseline demographic and general health characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sixteen children were included in our analysis. The average age at baseline was 12 years (SD: 3), 56.3% were male, and nearly all (93.8%) self-identified as Hispanic/Latino. Most of the children resided in-town (81.3%); 56.3% were from low-income families; and about 87.5% relied on public health insurance/aid. Approximately 69% of the children were taking corticosteroid medication at the time of enrollment, and 12 children (75.0%) were identified to be skin prick positive to at least one aeroallergen. Based on a clinical examination performed at baseline, more than half of the subjects (56.3%) were classified as overweight, defined as body mass index-for-age above the 85th percentile. We compared the subset of participants selected for our study with the main AFARE cohort (n=58), and found no significant differences in attributes likely to modify the exposure-outcome association (see Supplemental Table).

Table 1.

AFARE Sub-cohort Characteristics (N = 16)

| Variable | Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 9 (56.3) |

| Birth country | United States | 11 (68.8) |

| Other | 5 (31.3) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/ Latino | 15 (93.8) |

| Income | ≤ $15k/year | 9 (56.3) |

| Residence | In Town/Urban | 13 (81.3) |

| Rural | 3 (18.8) | |

| Total number of household members | < 5 | 5 (31.3) |

| ≥ 5 | 11 (68.8) | |

| Insurance | Public Insurance or Aid | 14 (87.5) |

| Private Insurance/Self | 2 (12.5) | |

| Skin prick test positive (atopy) | Yes | 12 (75.0) |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use | Yes | 11 (68.8) |

| Body mass index for age (85th percentile) | Above | 9 (56.3) |

| Age (years) | Median (IQR) | 11.0 (4.0) |

| Baseline fractional exhaled nitric oxide level (ppb) | Median (IQR) | 12.0 (12.0) |

| Creatinine adjusted Leukotriene E4 level (μg/g creatinine) | Median (IQR) | 84.8 (73.3) |

Compliance with collection of urine samples varied: the total number of samples per subject ranged from 1 to 12 (median: 10.5). A total of 139 observations were obtained from the 16 children over the study period. One observation was excluded because of incomplete data, resulting in 138 observations for analyses. The median level of creatinine-adjusted uLTE4 among participants was 84.8 μg/g creatinine (geometric mean: 84.8 μg/g) over the study period.

Pesticide exposure levels

OP metabolite concentrations are summarized in Table 2. Percentage above the limit of metabolite detection ranged between < 0.7% and 64.0%; DMTP and DMP were the most prevalent DAP metabolites (detected in approximately 64.0% and 35.3% of participants respectively), whereas DEDTP was the least prevalent metabolite (detected in < 0.7% of participants). The geometric mean (GM) of creatinine-adjusted EDE, EDM and EDAP were 81.0, 71.8 and 168.0 nmol/g respectively, and the two summed measures of DAP (EDE and EDM) were moderately correlated (ρ = 0.5; p = 0.1).

Table 2.

Concentrations of organophosphate pesticide urinary metabolites in study population

| Pesticide Metabolite (ng/mL) |

Unadjusted (nmol/L) |

Creatinine adjusted (nmol/g creatinine) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD | Percent > LOD |

Mean | GM | Median | IQR | Max | Mean | GM | Median | IQR | Max | |

| DEP | 1.0 | 28.8 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 31.0 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 57.7 |

| DETP | 1.0 | 28.8 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 28.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 20.5 |

| DEDTP | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 11.5 |

| DMP | 5.0 | 35.3 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 177.0 | 9.5 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 273.8 |

| DMTP | 5.0 | 64.0 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 384.0 | 10.9 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 594.0 |

| DMDTP | 2.5 | 18.7 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 43.2 |

| EDE | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 125.4 | 81.0 | 71.2 | 79.9 | 1324.9 |

| EDM | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 166.2 | 71.8 | 58.3 | 77.5 | 6591.1 |

| EDAP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 291.6 | 168.0 | 142.9 | 197.3 | 6696.8 |

• Abbreviations: LOD, limit of detection; GM, geometric mean; IQR, interquartile range; DMP, dimethyl phosphate; DMTP, dimethyl thiophosphate; DMDTP, dimethyl dithiophosphate; DEP, diethyl phosphate; DETP, diethyl thiophosphate; DEDTP, diethyl dithiophosphate; EDE, diethyl alkylphosphates; EDM, dimethyl alkylphosphate; EDAP, total dialkylphosphate.

• Metabolites were adjusted to creatinine standards of 100mg/dl.

Comparison with NHANES data

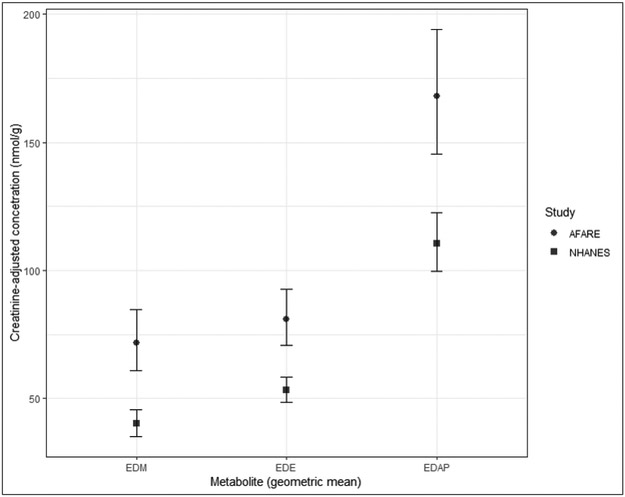

Figure 1 presents creatinine-adjusted geometric means and surrounding 95% confidence intervals for the total diethyl and dimethyl phosphate molar concentrations for children from our AFARE study and the NHANES study population. The distribution of summed DAP metabolite levels for children in the AFARE study were significantly higher than NHANES levels, with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction for comparing geometric means for all three measures resulted in p-values less than 0.05. The geometric mean of summed concentration of DAPs in the AFARE cohort were over 1.5 times that of the NHANES population (EDE: 81.0 vs. 53.1 nmol/g, EDM: 71.8 vs. 40.1 nmol/g, and EDAP: 168.0 vs. 110.6 nmol/g; all p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of creatinine-adjusted summed DAP metabolite distributions from AFARE children with distributions observed in children in NHANES. Abbreviations. EDE, diethyl alkylphosphate; EDM, dimethyl alkylphosphate; EDAP, total dialkylphosphate; AFARE, Aggravating Factors of Asthma in a Rural Environment study; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Relationships between DAP concentrations and uLTE4

Regression analyses demonstrated that IQR increases in the creatinine-corrected urinary concentration of summed DAPs (EDE: 79.9 nmol/g; EDM: 77.5 nmol/g; and EDAP: 197.3 nmol/g) was associated with increases in urinary LTE concentrations (βEDE: 9.3 (95%CI: 1.7, 16.9); βEDM: 0.9 (0.3, 1.6); βEDAP: 3.9 (−0.1, 7.9) all in μg/g creatinine, Table 3). These observed associations persisted after adjusting models for age, use of inhaled corticosteroids, allergy, maximum temperature and wind speed (βEDE: 8.7 (95%CI: 2.8, 14.6); βEDM: 1.1 (0.5, 1.7); βEDAP: 4.1 (0.7, 7.5) all in μg/g creatinine).

Table 3.

Observed increase in creatinine-adjusted uLTE4 levels per IQR increase in pesticide exposure

| Exposure | Urinary leukotriene Ɛ4 concentration (μg/g creatinine) |

|

|---|---|---|

| unadjusted β (95% CI) | adjusted β (95% CI) | |

| EDE | 9.3 (1.7, 16.9) | 8.7 (2.8, 14.6) |

| EDM | 0.9 (0.3, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.5, 1.7) |

| EDAP | 3.9 (−0.1, 7.9) | 4.1 (0.7, 7.5) |

• Separate models were fit for each exposure measure.

• Adjusted models included age, atopy (skin prick test positive to at least one common aeroallergen), use of control medication, wind speed and temperature.

• Abbreviations. EDE, diethyl alkylphosphates; EDM, dimethyl alkylphosphate; EDAP, total dialkylphosphate.

Discussion

Pesticides may be overlooked contributors to the risk of asthma and asthma exacerbation, especially among children. Our study provides novel evidence on the role of organophosphate pesticides as acute environmental triggers for worsening asthma morbidity among children with asthma.

Our results suggest that uLTE4 was associated with short-term exposure to OPs. The increases in uLTE4 levels were observed across summed measures of methyl DAPs and ethyl DAPs (EDE and EDM respectively), as well as total DAPs (EDAP). These findings extend the results of previous studies that suggest use of pesticides in homes or early life exposure may be associated with increased risk of asthma or wheezing.19-21,36 More specifically, due to its repeated measure design and biomarker based exposure assessment and outcome, our study provides unique insight into the adverse association between acute exposure to OPs in an agricultural community and pediatric asthma morbidity.

Cysteinyl leukotrienes are well known to play a major role in airway inflammation and asthma exacerbation.22,37,38 Urinary LTE4 serves as a stable indicator of cysteinyl leukotrienes pathway activity associated with asthma37,38 and has been recommended as a valid biomarker to predict risk of asthma exacerbation especially in acute settings. 23,38,39 In recent years researchers have used uLTE4 as a biomarker of adverse respiratory effect in environmental epidemiology. For example, Rabinovitch and colleagues conducted a longitudinal cohort study of asthmatic school children in Denver and found that the morning maximum ambient particulate matter concentrations were significantly associated with uLTE4.40 In a subsequent study, they also found that uLTE4 predicted severe asthma exacerbations among children exposed to tobacco smoke.39 Although the severity of asthma exacerbations are traditionally categorized using patient symptoms/signs and lung function tests,41 several studies have shown positive correlations between inflammatory markers, such as uLTE4, and measures of asthma morbidity (using traditional measurements as a proxy).38,39,42

Despite positive methyl DAP- and ethyl DAP-associations with uLTE4 observed among children, the effect estimate for EDE association was stronger than that of EDM. The reasons for this difference are unclear, but this result might suggest that the OP-related adverse respiratory effects identified in this community could stem largely from the OPs that devolve to DE metabolites (e.g., chlorpyrifos, diazinon).43

Our results also indicated that the geometric mean concentrations of the DAP metabolites observed in the AFARE cohort were higher than those observed in children of similar age in a representative US population (NHANES). The elevated levels of DAPs in our study, compared to US children, highlight the additional exposure burden (most likely ambient and proximity-based) encountered in populations with significant agricultural activity.9,10

Several mechanisms underlying OP-associated asthma morbidity have been suggested. OPs primarily inhibit various forms of cholinesterase, leading to excessive cholinergic activity in neuronal junctions of the parasympathetic nervous system responsible for modulating airway control.11,14,44 In addition, evidence from animal models and human epidemiology and toxicology studies suggest that other non-cholinergic mechanisms may be responsible for respiratory morbidity. While acute OP intoxication may induce a significant systemic inflammatory response with consequent pulmonary inflammation,45 low-level chronic exposures may result in disruption of muscarinic receptors activity in the airways, production of reactive oxygen species, and subsequent activation of a series of stress-responsive signaling pathways, or interaction with irritant receptors in the bronchial mucosa causing release of inflammatory mediators.44,45 However, future studies at the molecular level are needed to clarify the role of OPs in asthma morbidity.

Our study has a number of important limitations, most notably the use of DAPs as biomarkers of OP exposure. Although DAP metabolites in urine are considered an objective measure of OP exposures, pesticide-specific information cannot be derived from the quantitative measurement of these metabolites; consequently, we were unable to provide information on the specific OPs to which participants were exposed. Moreover, we were unable to provide information on the origin of the DAPs (environmentally preformed DAPs vs. metabolite DAPs resulting from exposure to the parent compounds). However, DAPs have been employed as a measure of OP exposure in numerous epidemiological studies and represent a non-invasive validated marker of broad exposure to OPs.21,28,29

We are limited by a lack of more traditional clinically-defined measures of asthma exacerbation like symptom reports, use of albuterol, and spirometry. Although we used uLTE4 as an inflammatory biomarker as with previous studies, we were unable to directly translate this marker to the clinical level/severity of asthma exacerbation. However, a few studies have provided some context for correlation between acute exacerbation events and uLTE4. For example, Rabinovitch et al. showed clinically significant decreases in pulmonary function (percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1-second, FEV1 by 4.7%) per IQR increase in uLTE4 among children with asthma.42

An additional study limitation is with regards to collection of urine samples. First morning void samples have been suggested as a more stable or representative measurement of exposures in urine.46 We believe that the longitudinal nature of our study, as well as using creatinine-adjusted values, minimizes issues of measurement variability in our population, providing more representative exposure information.

Finally, our study was conducted within an agricultural community, and as such levels of OP exposure are bound to be higher than in the general population. This limits our ability to generalize our results to these populations.

Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of understanding the role of OP exposure as a potential pediatric asthma exacerbator. Increased exposure to OP pesticides was associated with a marker of asthma exacerbation through inflammation in this cohort of children with asthma in an agricultural community in the United States.

Although there is a growing body of epidemiological and toxicological research exploring the associations between OP exposure and respiratory symptoms and conditions, there is limited evidence of effects of OPs in children with asthma. Future studies on OP-associated respiratory morbidity in children with asthma should consider including clinically defined measures of asthma exacerbation such as spirometry, medication use, and symptom days.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) K22-ES023815 (PI: Magzamen) and R21-ES17906 (PI: Karr).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

At the time this paper was written and submitted, there were no relevant financial or nonfinancial relationships to disclose for all named authors.

References

- 1.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Damon SA, Garbe PL, Breysse PN. Vital Signs : Asthma in Children — United States, 2001–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5):149–155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walls TA, Hughes NT, Mullan PC, Chamberlain JM, Brown K. Improving Pediatric Asthma Outcomes in a Community Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20160088. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federico MJ, Hoch HE, Anderson WC, Spahn JD, Szefler SJ. Asthma Management for Children. Adv Pediatr. 2016;63(1):103–126. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1581–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milligan KL, Matsui E, Sharma H. Asthma in Urban Children: Epidemiology, Environmental Risk Factors, and the Public Health Domain. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16(4). doi: 10.1007/s11882-016-0609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estrada RD, Ownby DR. Rural Asthma: Current Understanding of Prevalence, Patterns, and Interventions for Children and Adolescents. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17(6):37. doi: 10.1007/s11882-017-0704-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strosnider H, Kennedy C, Monti M, Yip F. Rural and Urban Differences in Air Quality, 2008–2012, and Community Drinking Water Quality, 2010–2015 — United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(13):1–10. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6613a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aneja VP, Schlesinger WH, Erisman JW. Effects of Agriculture upon the Air Quality and Climate: Research, Policy, and Regulations. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(12):4234–4240. doi: 10.1021/es8024403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu C, Fenske RA, Simcox NJ, Kalman D. Pesticide Exposure of Children in an Agricultural Community: Evidence of Household Proximity to Farmland and Take Home Exposure Pathways. Environ Res. 2000;84(3):290–302. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karr C Children’s Environmental Health in Agricultural Settings. J Agromedicine. 2012;17(2):127–139. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.658009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fryer AD. Mechanisms of organophosphate insecticide-induced airway hyperreactivity. AJP Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;286(5):L963–L969. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00343.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terry AV. Functional consequences of repeated organophosphate exposure: Potential non-cholinergic mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández AF, Casado I, Pena G, Gil F, Villanueva E, Pla A. Low Level of Exposure to Pesticides Leads to Lung Dysfunction in Occupationally Exposed Subjects. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20(9):839–849. doi: 10.1080/08958370801905524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Androutsopoulos VP, Hernandez AF, Liesivuori J, Tsatsakis AM. A mechanistic overview of health associated effects of low levels of organochlorine and organophosphorous pesticides. Toxicology. 2013;307:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamane a, Baldi I, Tessier J-F, Raherison C, Bouvier G. Occupational exposure to pesticides and respiratory health. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(136):306–319. doi: 10.1183/16000617.00006014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye M, Beach J, Martin JW, Senthilselvan A. Pesticide exposures and respiratory health in general populations. J Environ Sci. 2017;51:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordgren TM, Bailey KL. Pulmonary health effects of agriculture. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(2):144–149. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salam MT, Li YF, Langholz B, Gilliland FD. Early-life environmental risk factors for asthma: Findings from the children’s health study. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(6):760–765. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salameh PR, Baldi I, Brochard P, Raherison C, Abi Saleh B, Salamon R. Respiratory symptoms in children and exposure to pesticides. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):507–512. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00107403a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raanan R, Harley KG, Balmes JR, Bradman A, Lipsett M, Eskenazi B. Early-life Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and Pediatric Respiratory Symptoms in the CHAMACOS Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;123(2):179–185. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raanan R, Balmes JR, Harley KG, et al. Decreased lung function in 7-year-old children with early-life organophosphate exposure. Thorax. 2016;71(2):148–153. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu CY, Tsai MH, Yao TC, et al. Urinary LTE4 levels as a diagnostic marker for IgE-mediated asthma in preschool children: A birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szefler SJ, Wenzel S, Brown R, et al. Asthma outcomes: Biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3):S9–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson B, Griffith WC, Barr DB, Coronado GD, Vigoren EM, Faustman EM. Variability in the take-home pathway: Farmworkers and non-farmworkers and their children. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24(5):522–531. doi: 10.1038/jes.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coronado GD, Holte S, Vigoren E, et al. Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure and Residential Proximity to Nearby Fields. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(8):884–891. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318222f03a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loftus C, Yost M, Sampson P, et al. Ambient Ammonia Exposures in an Agricultural Community and Pediatric Asthma Morbidity. Epidemiology. 2015;26(6):794–801. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr DB. Biomonitoring of exposure to pesticides. J Chem Heal Saf. 2008;15(6):20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jchas.2008.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye M, Beach J, Martin JW, Senthilselvan A. Urinary Dialkyl Phosphate Concentrations and Lung Function Parameters in Adolescents and Adults: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;124(4):491–497. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradman A, Castorina R, Barr DB, et al. Determinants of Organophosphorus Pesticide Urinary Metabolite Levels in Young Children Living in an Agricultural Community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(12):1061–1083. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Amato G, Holgate ST, Pawankar R, et al. Meteorological conditions, climate change, new emerging factors, and asthma and related allergic disorders. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8(1):1–52. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damalas CA, Eleftherohorinos IG. Pesticide Exposure, Safety Issues, and Risk Assessment Indicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(5):1402–1419. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maxwell SK, Airola M, Nuckols JR. Using Landsat satellite data to support pesticide exposure assessment in California. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramaprasad J, Tsai MG-Y, Fenske R a, et al. Children’s inhalation exposure to methamidophos from sprayed potato fields in Washington State: Exploring the use of probabilistic modeling of meteorological data in exposure assessment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19(6):613–623. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Analytic guidelines, 1999-2010. Vital Heal Stat Ser 2 Data Eval Methods Res. 2013. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84884559811&partnerID=40&md5=ac26d43d490d58c249fb66965b751608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubbard AE, Ahern J, Fleischer NL, et al. To GEE or Not to GEE. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):467–474. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181caeb90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, Nembhard WN, Kan H, Becker A, Talbott EO. Residential Pesticide Use Is Associated With Childrenʼs Respiratory Symptoms. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(10):1281–1287. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31825cb6ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paruchuri S, Tashimo H, Feng C, et al. Leukotriene E 4 –induced pulmonary inflammation is mediated by the P2Y 12 receptor. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2543–2555. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green SA. Increase in urinary leukotriene LTE4 levels in acute asthma: correlation with airflow limitation. Thorax. 2004;59(2):100–104. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.006825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabinovitch N Urinary LTE4 Levels Identify Children with Tobacco Smoke Exposure At Risk for Asthma Exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;128(2):323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.035.Urinary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabinovitch N, Strand M, Gelfand EW. Particulate Levels Are Associated with Early Asthma Worsening in Children with Persistent Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1098–1105. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1393OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Asthma Control and Exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):59–99. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabinovitch N, Zhang L, Gelfand EW. Urine leukotriene E4 levels are associated with decreased pulmonary function in children with persistent airway obstruction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(3):635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouchard MF, Chevrier J, Harley KG, et al. Prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1189–1195. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernández AF, Parrón T, Alarcón R. Pesticides and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(2):90–96. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283445939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banks CN, Lein PJ. A review of experimental evidence linking neurotoxic organophosphorus compounds and inflammation. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33(3):575–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kissel JC, Curl CL, Kedan G, et al. Comparison of organophosphorus pesticide metabolite levels in single and multiple daily urine samples collected from preschool children in Washington State. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):164–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.