Abstract

Background and Aims:

A novel device that provides real-time depiction of functional luminal image probe (FLIP) panometry, ie, esophagogastric junction (EGJ) distensibility and distension-induced contractility was evaluated. We aimed to compare real-time FLIP panometry interpretation at the time of sedated endoscopy to high-resolution manometry (HRM) in evaluating esophageal motility.

Methods:

40 consecutive patients (ages 24 – 81; 60% female) referred for endoscopy with a plan for future HRM from two centers were prospectively evaluated with real-time FLIP panometry during sedated upper endoscopy. The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) and contractility profile were applied to derive a FLIP panometry classification at the time of endoscopy and again (post-hoc) using a customized program. HRM was classified according to the Chicago Classification.

Results:

Real-time FLIP panometry motility classification was abnormal in 29 (73%) patients, 19 (66%) of whom had a subsequent major motility disorder on HRM. All 9 patients with an HRM diagnosis of achalasia had abnormal real-time FLIP panometry classifications. 11 (33%) of patients had normal motility on real-time FLIP panometry and 8 (73%) had a subsequent HRM without a major motility disorder. There was excellent agreement (kappa = 0.939) between real-time and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation of abnormal motility.

Conclusions:

This prospective, multi-centered study demonstrated that real-time FLIP panometry could detect abnormal esophageal motility, including achalasia, at the endoscopic encounter. Additionally, normal motility on FLIP panometry was predictive of a benign HRM. Thus, real-time FLIP panometry incorporated with endoscopy appears to provide a suitable and well tolerated point-of-care esophageal motility assessment.

Keywords: manometry, impedance, peristalsis, achalasia, dysphagia

Introduction

The functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) uses high-resolution impedance planimetry to measure luminal dimensions concurrently with distensive pressure, and thus distensibility (ie, the relationship of luminal dimensions and distensive pressure).1–3 Additionally, esophageal contractility can be elicited by FLIP distension, evident by occluding and nonoccluding contractions along the FLIP probe.4, 5 This comprehensive evaluation of esophageal function that incorporates esophagogastric junction (EGJ) distensibility and distension-induced contractility, termed FLIP panometry, provides a novel method to evaluate esophageal motility at the time of endoscopy.6, 7 We previously reported that FLIP panometry could effectively detect abnormal esophageal motility, including achalasia among patients being evaluated for non-obstructive dysphagia.6 Furthermore, FLIP panometry identified abnormalities in EGJ distensibility or the contractile response to distension in patients that otherwise had normal motility on HRM.

A practical limitation of the use of panometry as described above was the reliance on a customized analysis program to generate the FLIP panometry plots and the esophageal motility impression.6 Consequently, although completing the FLIP test at the time of upper endoscopy provided a well-tolerated test for patients, the postprocedural analysis introduced a delay in the FLIP diagnostic impression, thereby limiting the ability to act on the result during that same endoscopic encounter. However, an updated device that displays 40 seconds of continuous FLIP panometry output recently became commercially available (FLIP 2.0; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, Minn) offering the potential for broader application and real-time interpretation at the time of endoscopy. Thus, the aims of this study were to evaluate the feasibility of interpretation of esophageal motility at the time of endoscopy using real-time FLIP panometry by assessing (1) the correlation between FLIP panometry with high-resolution manometry (HRM), and (2) the agreement between real-time interpretation and postendoscopic interpretation of FLIP panometry.

Methods

Patients

Patients presenting to the Esophageal Center of Northwestern and the Gastroenterology clinics of Washington University School of Medicine for evaluation of dysphagia, esophageal chest pain, or reflux symptoms between June 2017 and February 2018 were prospectively enrolled. Patients with a management plan for HRM to follow endoscopy were identified for inclusion. Thus, the HRM diagnosis was not known at the time of the endoscopic evaluation. Patients with previous upper gastrointestinal surgery, significant medical comorbidities, eosinophilic esophagitis, severe reflux esophagitis (LA-classification C or D), or large hiatal hernia were excluded. Enrollment was blocked to include 10 consecutive eligible patients for each of 4 raters (D.A.C., C.P.G., P.J.K., and J.E.P.) to yield a total cohort of 40 patients. The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University and Washington University Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

FLIP

The 16-cm FLIP (EndoFLIP EF-322N; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, Minn) was calibrated to atmospheric pressure before transoral probe placement. With the endoscope withdrawn, the FLIP was positioned within the esophagus such that 1 to 3 impedance sensors were observed beyond the EGJ with this positioning maintained throughout the FLIP study. Stepwise, 10 mL balloon distensions beginning with 20 ml and increasing to target volume of 70 ml were then performed; each stepwise distension volume was maintained for 30 to 60 seconds.

Subjects underwent sedated upper endoscopy in the left lateral decubitus position. Upper endoscopy was completed using sedation with midazolam (3 – 13 mg) and fentanyl (75 – 250 µg); propofol (possibly in addition to midazolam and fentanyl) was used with anesthesiologist assistance at the discretion of the performing endoscopist in some cases.

High resolution manometry

Manometry studies were completed using a 4.2-mm outer diameter solid-state assembly with 36 circumferential pressure sensors at 1-cm intervals (Medtronic Inc, Shoreview, Minn). After a minimum 6-hour fast, the HRIM assembly was placed trans-nasally and positioned to record from the hypopharynx to the stomach with approximately 3 intragastric pressure sensors. The HRM protocol included a 5-minute baseline recording, ten 5-mL swallows in a supine position using 50% saline solution for test swallows at 20 to 30 second intervals.8, 9

Analysis

Real-time FLIP panometry

The real-time FLIP panometry display (FLIP 2.0 system; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, Minn) provided 40-seconds of continuous, real-time data output that included distension volume, intra-balloon pressure, and 16 channels of color-coded luminal diameters as a topographic plot generated via interpolation between channels. The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) was calculated by the real-time software as luminal cross-sectional area divided by pressure with the DI values displayed on the real-time monitor for all 16 impedance-planimetry channels.3 The DI corresponding to the narrowest diameter along the probe was highlighted by a change in color.

Each of the four FLIP panometry raters were provided with a brief (20-slides) tutorial for real-time FLIP panometry interpretation. A score sheet was used to capture results of interpretation in real-time during the endoscopic encounter. Interpreters were instructed to use the EGJ-DI (ie, the DI generated from the narrowest diameter across the EGJ) obtained during 60-mL fill volume portion of the FLIP study for clinical interpretation; in the case of EGJ-DI value fluctuation, a median EGJ-DI value was estimated. Focus on the 60-mL fill volume for the primary EGJ-DI assessment was chosen to maintain measurement consistency using the standardized fill volume reported in previous studies.5–7 An abnormal EGJ-DI was determined if the EGJ-DI was <2.8 mm2/mm Hg, which was classified as Reduced EGJ Opening (REO); EGJ-DI was ≥2.8 mm2/mmHg was classified as normal EGJ opening.2, 3, 5–7

The pattern of distension-induced contractility was assessed over the entirety of the FLIP study (20 mL – 70 mL fill volumes). An esophageal contraction, ie, presence of contractility, was defined as occurring when esophageal body diameter changes of >5 mm occurred in >2 adjacent impedance planimetry channels.4–7 Direction of contraction propagation was assessed as antegrade or retrograde. A repetitive pattern of contractility was defined as when ≥3 consecutive contractions of similar morphology (and directionality) occurred. Repetitive contractions could be antegrade (RACs) or retrograde (RRCs). In summary, contractility could be present or absent and when present could include a RAC pattern and/or a RRC pattern.

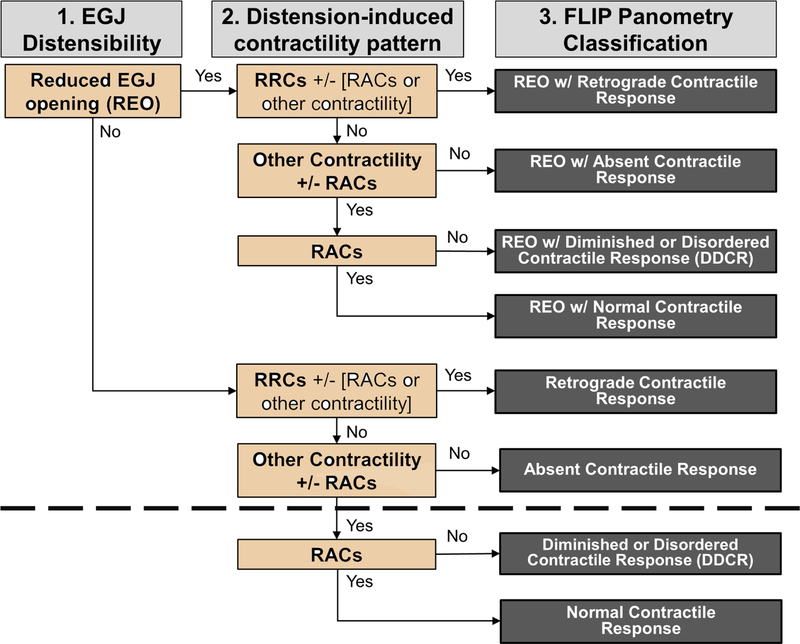

Finally, a FLIP panometry motility classification was generated in a hierarchical fashion by first applying the EGJ-DI to assess EGJ opening and then considering the pattern of the distension-induced contractility (Figure 1).6 FLIP panometry motility classifications not observed in asymptomatic volunteers were considered abnormal FLIP panometry, whereas those observed in asymptomatic volunteers were considered normal FLIP panometry.4–7

Figure 1. Classification of esophageal motility in response to distension via FLIP Panometry.

(1) Presence (or absence) of reduced esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening (REO) was assessed via EGJ-distensibility index (DI). (2) Contractile response to distension was assessed via the distension-induced contractility pattern. (3) A FLIP panometry classification was designated. Classifications above the dashed line were considered abnormal FLIP panometry, ie, not observed in asymptomatic controls.6, 7 RRCs – repetitive, retrograde contractions; RACs – repetitive, antegrade contractions. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center at Northwestern.

Post-hoc FLIP panometry

FLIP studies were also exported to MATLAB (The Math Works, Natick, Mass, USA) for analysis using a customized program as previously described after the endoscopic encounter. 4–7, 10 The program identified the EGJ-midline by searching for the minimal diameter of the distal impedance planimetry channels. The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) was then calculated by dividing the median EGJ-midline cross-sectional area (CSA) by the median intraballoon pressure over the duration of the 60-mL distension volume: median CSA/median pressure = EGJ-DI in mm2/mm Hg. The FLIP topography plot and 16 channel diameter line tracing output were used to assess esophageal body contractions using the same criteria as stated above for real-time interpretation. Finally, a FLIP panometry motility classification was rendered (Figure 1).6

High resolution manometry

Manometry studies were analyzed using ManoView version 3.0 analysis software to measure basal EGJ pressure (EGJP) at end-expiration, the 4s integrated relaxation pressure (IRP), distal contractile integral (DCI), and distal latency.8, 9 The esophageal motility diagnosis was generated from the ten supine swallows according to the Chicago Classification v3.0, using a median IRP of 15 mm Hg as the upper limit of normal.9 Achalasia, EGJ outflow obstruction (EGJOO), absent contractility, distal esophageal spasm, or jackhammer esophagus were considered major motility disorders (ie, those not observed in asymptomatic controls), whereas ineffective esophageal motility, fragmented peristalsis, and normal motility were considered as HRM without a major motor disorder for the purpose of dichotomous analysis.8, 9

Statistical analysis

Variables are presented as mean (SD), percentage (frequency), and median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Bivariate correlation was evaluated with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Agreement between the real-time FLIP panometry interpretation and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation was assessed using Fleiss’ kappa (κ) statistic. Degree of agreement was interpreted based on kappa values as poor (0–0.2), fair (0.21–0.4), moderate (0.41–0.6), good (0.61–0.8), and excellent (0.81–1).

Results

Patients

Of the 40 enrolled patients, 60% were female and the mean (range) age was 57 (24 – 81) years. The indication for evaluation was dysphagia in 32 (80%), reflux symptoms in 6 (15%), chest pain in 1 (3%), and cough in 1 (3%). The endoscopic sedation used was conscious sedation in 27 (67%) patients with mean (standard deviation) dosages of 7.7 (2.3) mg midazolam and 166 (43) mcg fentanyl. Propofol was used in the remaining 13 (33%) patients. At endoscopy, 6 patients (15%) had a small (<3 cm) hiatal hernia, but the endoscopies were otherwise normal. HRM was performed on the same day, but after endoscopy and FLIP, in 28 (70%) of patients; in the remaining 12 patients, HRM was performed a median (range) of 43 (1 – 140) days after endoscopy and FLIP.

Motility evaluation with real-time FLIP panometry

The FLIP study lasted a mean (SD) 4.3 (0.9) minutes and a FLIP panometry motility classification was successfully derived shortly after completion of the FLIP study (ie, at the time of endoscopy) in all 40 patients. An abnormal FLIP panometry classification was reached in 29 (73%) patients. Among these abnormal FLIP panometries, REO (EGJ-DI <2.8 mm2/mm Hg) was identified in 25 of 29 patients (86%; 63% of the total cohort) with median (IQR; range) EGJ-DI of 0.9 mm2/mm Hg (0.5 – 1.2; 0.2 – 2.0). Contractile response patterns among the 25 patients with REO included an absent contractile response in 11 (44%), retrograde contractile response in 6 (24%), diminished or disordered contractile response (DDCR) in 4 (16%), and normal contractile response in 4 (16%). Of the remaining four patients with abnormal FLIP panometry, but normal EGJ opening (EGJ-DI range 2.9 – 6.0 mm2/mm Hg), 2 had an absent contractile response and 2 had a retrograde contractile response.

A normal FLIP panometry was observed in 11 (28%) patients. The median (IQR; range) EGJ-DI among these patients was 4.2 mm2/mm Hg (3.8 – 10; 3.5 – 12). All 11 had a RAC pattern observed and were classified as normal contractile response.

HRM results

On HRM that occurred after endoscopy with FLIP, a major motor disorder was diagnosed in 22 (55%) patients: 9 (23%) with achalasia (1 type I, 3 type II, and 5 type III achalasia), 10 (25%) EGJOO, 1 (3%) distal esophageal spasm, and 2 (5%) jackhammer esophagus; none of the patients had a HRM-diagnosis of absent contractility. The remaining 18 (45%) did not have a major motor disorder on HRM: 4 (10%) had ineffective esophageal motility and 14 (45%) had normal motility.

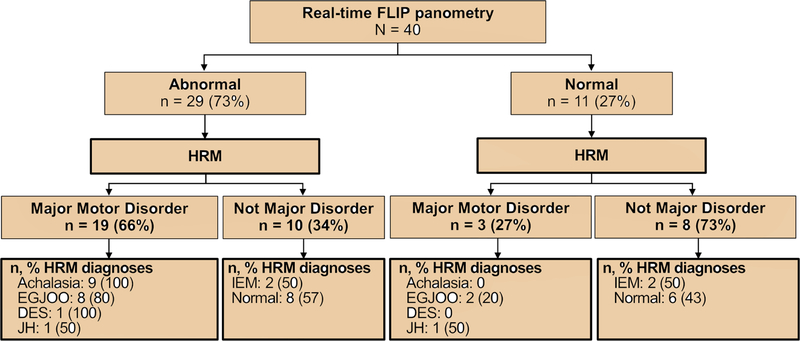

Relationship of FLIP panometry motility classification with HRM

The relationship between FLIP panometry classification and HRM-Chicago Classification are displayed in Table 1. Of the 29 patients with an abnormal FLIP panometry, 19 (66%) went on to have an abnormal HRM, whereas 10 (34%) subsequently had an HRM without a major motor disorder (Figure 2). From the other perspective, of the 22 patients that subsequently had an abnormal HRM, 19 (87%) had a preceding abnormal FLIP panometry. All 9 patients with achalasia on HRM had an abnormal FLIP panometry, which included REO (EGJ-DI range 0.3 – 1.5 mm2/mmHg) and an abnormal contractile response to distension (Figure 3). Ten of 18 patients (56%) that had an HRM without a major motor disorder per the Chicago Classification (2 with IEM, 8 with normal motility) had an abnormal FLIP panometry (Figure 4A–C).

Table 1. Relationship of real-time FLIP panometry and high-resolution manometry esophageal motility diagnoses.

EGJOO – esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. REO – Reduced EGJ Opening. DDCR – diminished or disordered contractile response. IEM – ineffective esophageal motility

| FLIP Panometry motility classification (n, % HRM diagnosis) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRM diagnosis | n | REO with retrograde contractile response | REO with absent contractile response | REO with DDCR | REO with normal contractile response | Absent Contractile Response | Retrograde Contractile Response | DDCR | Normal contractile response |

| N | 6 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 11 | |

| Type I Achalasia | 1 | 1 (100) | |||||||

| Type II Achalasia | 3 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | ||||||

| Type III achalasia | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | ||||||

| EGJOO | 10 | 1 (10) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | |||

| Distal esophageal spasm | 1 | 1 (100) | |||||||

| Jackhammer | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | ||||||

| IEM | 4 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | |||||

| Normal | 14 | 1 (7) | 2 (14) | 2 (14) | 1 (7) | 2 (14) | 6 (43) | ||

Figure 2. Relationship of FLIP panometry and high-resolution manometry (HRM) motility classification.

EGJOO - esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. DES – distal esophageal spasm. JH – jackhammer esophagus. IEM – ineffective esophageal motility. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center at Northwestern.

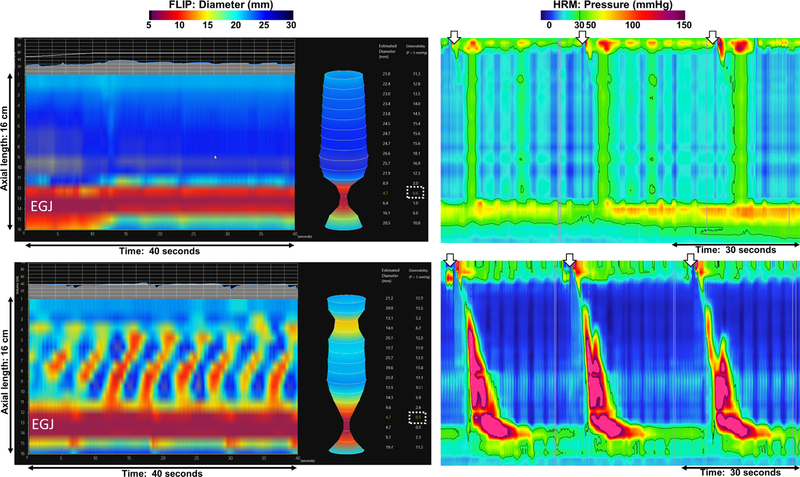

Figure 3. Achalasia on FLIP panometry.

The real-time FLIP panometry display included 40 seconds of data with FLIP topography (representing 16-cm of axial length) below the continuous output of pressure and fill volume. The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) could be recognized by the area of narrow diameter on the FLIP topography plot and the waist in the instantaneous display of the FLIP balloon to the right. The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) was displayed on the right of the display (dashed white boxes). Several swallows (white arrows) from corresponding high-resolution manometries are also displayed (far right). A, The EGJ-DI was 0.6 mm2/mm Hg at the 60ml FLIP fill volume (displayed) whereas there was an absent contractile response throughout the duration of the FLIP study, yielding a classification of reduced EGJ opening (REO) with absent contractile response. On HRM, the median integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) was 29 mm Hg with absent contractility and panesophageal pressurization: type II achalasia. B, Repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs) were observed at the 40 mL (displayed) and 50 mL fill volume and the EGJ-DI was 0.4 mm2/mm Hg at the 60ml FLIP fill volume. FLIP panometry was classified as REO with retrograde contractile response. On HRM, the median integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) was 21 mm Hg with premature contractility (distal latencies 4 seconds): type III achalasia. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center at Northwestern.

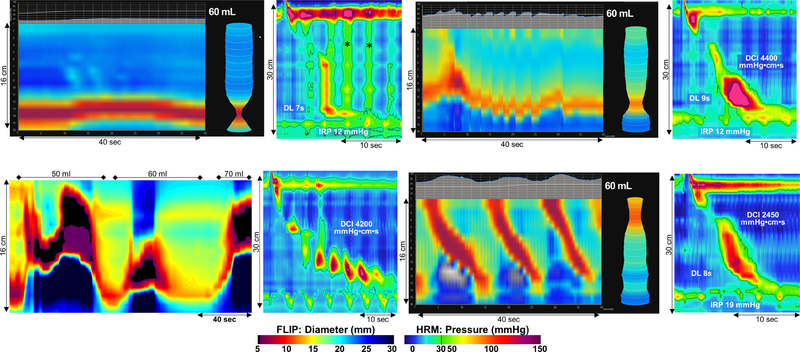

Figure 4. Examples of discordant FLIP panometry and HRM-derived motility classifications.

FLIP output (left: real-time display for A, B, D; post-hoc program generated topography for C) and a single supine swallow on HRM (right) from 4 patients are displayed. A, Real-time FLIP panometry classification was of abnormal motility: Reduced EGJ Opening (REO), EGJ-distensibility index, DI = 0.7 mm2/mm Hg, with an absent contractile response, while strict application of the Chicago Classification to the HRM yielded a classification of ineffective esophageal motility with a median integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) 13 mm Hg and 6/10 ineffective swallows. However, given the observed intermittent pan-esophageal pressurization (*), an early or evolving motor disorder was suspected. B, Real-time FLIP panometry classification was of abnormal motility: REO, EGJ-DI = 1.8 mm2/mm Hg, with diminished or disordered contractile response. The HRM was classified as normal motility with a median IRP of 14 mmHg. On esophagram, a 12.5 mm barium tablet became impacted at the EGJ. The patient underwent a second upper endoscopy at which time a balloon dilation to 19 mm caused a mucosal disruption at a subtle EGJ-stricture. C, Real-time FLIP panometry was classified as abnormal as absent contractile response (of the esophageal body) and an EGJ-DI of 2.9 mm2/mm Hg. The esophageal shortening events with prolonged contraction of the lower esophageal sphincter were observed. Strict application of the Chicago Classification to the HRM yielded a classification of normal motility with a median IRP of 7 mm Hg and 10/10 swallows with a distal contractile integral (DCI) between 1400 and 3500 mm Hg•cm•s, despite the HRM-contractile pattern of repetitive contractions. The patient underwent a second upper endoscopy at which time a subtle ring at the squamocolumnar junction was observed that was disrupted with biopsy forceps and a balloon dilation to 20 mm was performed; low dose nortriptyline was also prescribed. The presenting symptoms of solid-food dysphagia, retrosternal pain, and belching completely resolved. D, Real-time FLIP panometry classification was of normal motility with EGJ-DI of 3.8 mm2/mm Hg) and a normal contractile response (pattern of repetitive antegrade contractions observed). The HRM was classified as EGJ outflow obstruction with a median IRP of 20 mmHg and normal peristalsis. The elevated IRP was ultimately attributed to pressure artifact. DL – distal latency. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center at Northwestern.

Of the 11 patients that had a normal FLIP panometry, 8 (73%) had an HRM without a major motor disorder. Of the 3 patients that had normal FLIP panometry, but abnormal HRM, one had an HRM diagnosis of EGJOO with a median IRP of 20 mm Hg and had a timed-barium esophagram with normal clearance of barium by 1 minute and normal passage of a 12.5 mm barium tablet: the elevated IRP and EGJOO was ultimately attributed to pressure artifact; Figure 4D. The second had an HRM diagnosis of EGJOO with median IRP of 17 mm Hg that was attributed to a small hiatal hernia (peristalsis was otherwise normal). The third had an HRM diagnosis of jackhammer esophagus based on 2 of 10 swallows with a DCI >8000 mm Hg•cm•s in the setting of a hiatal hernia.

Of the 6 patients that were evaluated with a primary indication of reflux symptoms, all had normal EGJ opening (ie, normal EGJ-DI) and 4 of 6 had a normal contractile response; the remaining two patients were classified as absent contractile response and retrograde contractile response. The patient evaluated primarily for chronic cough (and occasional dysphagia) had a FLIP panometry classification of REO with retrograde contractile response and an HRM with distal esophageal spasm. The patient evaluated for chest pain had a FLIP panometry classification of REO with normal contractile response and an HRM with EGJOO. The remainder of the patients (n = 32) were evaluated for non-obstructive dysphagia.

Agreement between real-time FLIP panometry interpretation and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation

There was excellent agreement (κ = 0.939; P < 0.001) between real-time FLIP panometry interpretation and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation with regard to designating abnormal or normal FLIP panometry classification; percent agreement was 39 of 40 (98%) patients. The lone disagreement was with a patient with absent contractile response interpretation in real-time and DDCR on the post-hoc analysis; the HRM was IEM. The correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) between real-time EGJ-DI and post-hoc EGJ-DI was 0.922 (P < 0.001). There was excellent agreement for reduced or normal EGJ opening (κ = 0.946; P < 0.001), with percent agreement of 98% (39/40). The lone disagreement had real-time assessment of EGJ-DI of 2.9 mm2/mmHg and a post-hoc EGJ-DI calculation of 1.1 mm2/mmHg; the HRM diagnosis by strict application of the Chicago Classification was normal motility even though abnormal motility was suspected (Figure 4C). There was good agreement (κ = 0.643; P < 0.001) between real-time and post-hoc FLIP panometry motility classification with percent agreement of 70% (28/40); Table 2. The most common scenario for disagreement (5/12, 42%, disagreements) was interpretation of REO with absent contractile response in real-time and REO with DDCR on post-hoc interpretation (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2. Agreement in real-time and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation.

Shaded boxes indicate agreement. The HRM classification for this patient* was type III achalasia and among these 5 patients** included 2 type III achalasia, 1 type II achalasia, 1 esophagogastric junction (EGJ) outflow obstruction, and 1 normal motility. REO – Reduced EGJ Opening. DDCR – diminished or disordered contractile response

| Real-time interpretation - FLIP Panometry motility classification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-hoc interpretation | n | REO with retrograde contractile response | REO with absent contractile response | REO with DDCR | REO with normal contractile response | Absent Contractile Response | Retrograde Contractile Response | DDCR | Normal contractile response | |

| n | 6 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 11 | ||

| Post-hoc interpretation | REO with Retrograde contractile response | 7 | 6 | 1* | ||||||

| REO with Absent contractile response | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| REO with DDCR | 11 | 5** | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| REO with normal contractile response | 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| Absent Contractile Response | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Retrograde Contractile Response | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| DDCR | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| Normal contractile response | 9 | 9 | ||||||||

Discussion

In a prospective, multicenter study, we evaluated the esophageal motility assessment at the time of endoscopy using real-time FLIP panometry and found that major motor disorders, particularly achalasia, were effectively identified. All 9 patients that had achalasia subsequently diagnosed on HRM also had an abnormal FLIP panometry classification with reduced EGJ opening and an abnormal contractile response to distension. Additionally, an interpretation of normal motility on FLIP panometry at the time of endoscopy was generally associated with a normal subsequent HRM. Overall, these findings suggest that FLIP panometry may provide an accurate esophageal motility assessment at the time of sedated endoscopy, potentially improving patient tolerance and convenience as compared with the traditional manometric evaluation.

In a previous study describing esophageal motility evaluation with FLIP panometry, we reported that FLIP panometry effectively identified non-obstructive dysphagia patients with abnormal HRM.6 Recognition of achalasia, the prototypical primary esophageal motility disorder, is an essential component of esophageal motility assessment and similar to the present study, FLIP panometry was abnormal in all patients that had achalasia diagnosed with HRM: 70 of 70 patients with achalaia in the previous study.6 However, the previous study interpreted esophageal motility on FLIP panometry via postendoscopic processing using a customized program, which limited both the generalizability and immediate utilization of the FLIP panometry interpretation.6 The use of a novel, commercially available display system in the present study addressed these limitations. Additionally, systematic evaluation of the real- time interpretation of FLIP panometry across 2 centers and 4 raters starts to explore the broader application of real-time FLIP panometry. However, generalizability may remain limited as the four raters participating have significant experience with esophageal motility evaluation.

Also consistent with the previous study, abnormal FLIP panometry was observed among a moderate proportion of patients with normal motility (or IEM) on HRM. In the current study, this scenario occurred in 8/14 (57%) patients with normal motility on HRM, whereas it occurred in 15 of 29 (52%) patients with normal motility in the previous study.6 However, both of these studies represent clinical evaluation of symptomatic patients, in which a finding of “normal” motility implied that a cause of symptoms remained unidentified on HRM. An abnormality in the biomechanical properties of the EGJ may be reflected by an abnormal response to distension (ie, a low EGJ-DI), but not by an abnormal lower esophageal sphincter relaxation pressure (ie, the IRP). Additionally, abnormalities in secondary peristalsis, which are likely reflected as an abnormal contractile response on FLIP panometry, were previously reported in both patients with non-obstructive dysphagia (like the majority of patients in this study) and GERD.11–14 However, while abnormal FLIP panometry was often seen among patients with subsequent normal HRM, normal FLIP panometry almost universally led to a benign esophageal motility impression. Even though there were 3 of 11 patients with normal FLIP panometry and abnormal HRMs, the clinical significance of the HRM abnormalities appeared minimal: marginal IRP elevations in the 2 patients with HRM-EGJOO, and hypercontractile esophagus potentially secondary to the small hiatal hernia in the third.

In contemplating the imperfect correspondence between the FLIP panometry motility assessment and HRM, these techniques do assess different aspects of esophageal physiology: the esophageal response to distension versus primary peristalsis. Additionally, we recognize that HRM is not a perfect diagnostic tool (eg, susceptibility to pressure artifacts) and the Chicago Classification is not a perfect classification scheme (eg, Figure 4, A and C in particular).9 Thus, clinical uncertainty can persist despite HRM diagnoses. Further, motility assessment with FLIP panometry is a relatively new application of this technology and the analysis paradigm and classification scheme used in this study will likely evolve with continued use and broader application, similar to the evolution observed with HRM and the Chicago Classification.8, 9, 15 Ultimately, the objective in esophageal motility evaluation with FLIP panometry is not necessarily to reproduce HRM findings, but rather to detect functional abnormalities with clinical significance. Even within this relatively modest clinical sample size, several examples were observed in which abnormalities on FLIP panometry were related to subtle findings amenable to endoscopic interventions (Figure 4B and 4C); results of this study lend support to applying the FLIP panometry findings to guide endoscopic decisions at the time of the initial endoscopy. Unfortunately, the current study is limited in evaluation of clinical outcomes as a standardized treatment plan or follow-up protocol was not incorporated. Thus, future studies to evaluate whether or not patients with a discrepancy between FLIP panometry and HRM findings have clinically significant disease are needed.

Another important finding in the current study was of excellent agreement between real-time and post-hoc FLIP panometry interpretation for detection of EGJ outflow obstruction and major motility abnormalities. This provides reassurance that results from studies in which FLIP panometry was interpreted with post-hoc interpretation are applicable to studies (and clinical practice) using real-time FLIP panometry.5–7 With respect to FLIP panometry motility interpretation, there was still good agreement between real-time and post-hoc studies, but discrepancies were observed in the designation of the FLIP-panometry contractile pattern. These often involved detection of subtle contractions on post-hoc interpretation that were not appreciated in real-time leading to a DDCR interpretation. This may have been related to difficulty in quantifying small-caliber diameter changes in real-time (easier in the post-hoc setting) or to filtering algorithms incorporated into the real-time display. Modifying the filtering on the real-time display may foster improved agreement in future utilization, as may future analysis software when it becomes available.

In conclusion, we prospectively evaluated 40 patients across 2 centers and 4 raters and demonstrated that esophageal motility interpretation at the time of upper endoscopy effectively identified major esophageal motor disorders and normal motility as verified by HRM. Demonstration that esophageal motility evaluation with real-time FLIP panometry performs similarly and agrees well with post-endoscopic analysis supports generalizability of previous FLIP panometry studies to research and clinical use of real-time FLIP interpretation. Thus, motility evaluation with FLIP panometry during sedated endoscopy is feasible and effective and may reduce the need for manometry (along with the discomfort associated with the transnasal catheter placement) in some patients, such as when normal FLIP panometry is observed during a nonobstructive dysphagia evaluation and the focus can instead shift toward reflux or functional dysphagia management. Alternatively, an abnormal FLIP panometry may direct when HRM should be obtained to confirm or complement FLIP panometry findings. Although further study is needed to optimize FLIP panometry motility evaluation and further investigate the application of FLIP panometry motility assessment for other indications (eg, reflux), real-time FLIP panometry incorporated with endoscopy appears poised to become a valuable addition to patient-centered management of esophageal symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by R01 DK079902 (JEP) and P01 DK117824 (JEP, THT) from the Public Health service.

Glossary

- CSA

cross-sectional area

- DDCR

diminished or disordered contractile response

- DI

distensibility index

- DCI

distal contractile integral

- EGJ

esophagogastric junction

- DES

distal esophageal spasm

- DL

distal latency

- EGJOO

EGJ outflow obstruction

- FLIP

functional luminal image probe

- HRM

high-resolution manometry

- IEM

ineffective esophageal motility

- IRP

integrated relaxation pressure

- IQR

interquartile range

- JH

jackhammer esophagus

- RACs

repetitive antegrade contractions

- RRCs

repetitive retrograde contractions

- REO

Reduced EGJ Opening

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dustin A. Carlson, Peter J. Kahrilas, Zhiyue Lin, and John E. Pandolfino hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic Inc.

Dustin A. Carlson: Medtronic (Speaking. Consulting)

C. Prakash Gyawali: Medtronic, Diversatek (Speaking, Consulting); Torax, Ironwood, Quintiles (consulting)

Peter J. Kahrilas: Ironwood (Consulting)

John E. Pandolfino: Crospon, Inc (stock options), Given Imaging (Consultant, Grant, Speaking), Sandhill Scientific (Consulting, Speaking), Takeda (Speaking), Astra Zeneca (Speaking), Medtronic (Speaking. Consulting), Torax (Speaking, Consulting), Ironwood (Consulting), Impleo (Grant).

Joseph R. Triggs, Sophia Falmagne, Jacqueline Prescott, Emily Dorian, Wenjun Kou: none.

References

- 1.Kwiatek MA, Pandolfino JE, Hirano I, et al. Esophagogastric junction distensibility assessed with an endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP). Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rohof WO, Hirsch DP, Kessing BF, et al. Efficacy of treatment for patients with achalasia depends on the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology 2012;143:328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfino JE, de Ruigh A, Nicodeme F, et al. Distensibility of the esophagogastric junction assessed with the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) in achalasia patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013;25:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Rogers MC, et al. Utilizing functional lumen imaging probe topography to evaluate esophageal contractility during volumetric distention: a pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, et al. The Functional Lumen Imaging Probe Detects Esophageal Contractility Not Observed With Manometry in Patients With Achalasia. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson DA, Kou W, Lin Z, et al. Normal Values of Esophageal Distensibility and Distension-Induced Contractility Measured by Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:674–81 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, et al. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, Xiao Y, et al. Functional luminal imaging probe topography: an improved method for characterizing esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2013;6:97–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Gut 1994;35:1523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Integrity and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 1995;36:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CL, Szczesniak MM, Cook IJ. Identification of impaired oesophageal bolus transit and clearance by secondary peristalsis in patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:980–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwakiri K, Hayashi Y, Kotoyori M, et al. Defective triggering of secondary peristalsis in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:2208–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Chicago Classification Criteria of Esophageal Motility Disorders Defined in High Resolution Esophageal Pressure Topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.