Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to perform a quantitative analysis of the structural and functional alterations in the intervertebral disc during in vivo degeneration, using emerging tools that enable rigorous assessment from the microscale to the macroscale, as well as to correlate these outcomes with noninvasive, clinically relevant imaging parameters.

Design:

Degeneration was induced in a rabbit model by puncturing the annulus fibrosus (AF) with a 16-gauge needle. 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks following puncture, degenerative changes in the discs were evaluated via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whole motion segment biomechanics, atomic force microscopy, histology and polarized light microscopy, immunohistochemistry, biochemical content, and second harmonic generation imaging.

Results:

Following puncture, degeneration was evident through marked changes in whole disc structure and mechanics. Puncture acutely compromised disc macro and microscale mechanics, followed by progressive stiffening and remodeling. Histological analysis showed substantial anterior fibrotic remodeling and osteophyte formation, as well as an overall reduction in disc height, and disorganization and infolding of the AF lamellae into the NP space. Increases in NP collagen content and aggrecan breakdown products were also noted within 4 weeks. On MRI, NP T2 was reduced at all post-puncture time points and correlated significantly with microscale indentation modulus.

Conclusion:

This study defined the time dependent changes in disc structure-function relationships during IVD degeneration in a rabbit annular injury model and correlated degeneration severity with clinical imaging parameters. Our findings identified AF infolding and occupancy of the space as a principle mechanism of disc degeneration in response to needle puncture, and provide new insights to direct the development of novel therapeutics.

Keywords: intervertebral disc degeneration, animal model, magnetic resonance imaging, atomic force microscopy

Introduction

The intervertebral discs (IVD) of the spine are the soft tissues that connect adjacent vertebral bodies, and are comprised of multiple distinct anatomical regions1. The inner nucleus pulposus (NP) is a viscous structure, containing type II collagen and hydrated proteoglycan molecules, primarily aggrecan2. The NP is surrounded circumferentially by the annulus fibrosus (AF), composed of type I and type II collagen fibrils, arranged at alternating oblique angles to form concentric lamellae3. The NP and AF act synergistically to transfer loads within the spine, such that when the disc is compressed, pressure is generated within the NP which expands radially, placing the AF in tension4.

During degeneration, the mechanical function of the disc is compromised. Specifically, IVD degeneration is marked by a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional, and structural alterations5. In humans, one of the earliest hallmarks of degeneration is observed in the NP, where decreased aggrecan content and NP fibrosis leads to reduced hydration and impaired mechanical function6,7. With advanced degeneration, there is an eventual loss of disc height and mechanical failure of the entire joint8. IVD degeneration is frequently associated with low back pain, which is the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years in the United States9. Despite the significant clinical burden of IVD degeneration, the underlying mechanisms of disease onset and progression are poorly understood, hampering early clinical diagnosis and the development of novel treatments to interrupt or reverse disease progression.

To that end, a number of animal models have been developed to understand disease progression and evaluate new IVD therapeutics. The rabbit is a frequently used model, as injury (via needle puncture) to the AF induces rapid and progressive IVD degeneration recapitulating several hallmarks of human disease10. Multiple groups have demonstrated the reproducibility of this model, characterizing degeneration through radiographic, qualitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and histologic analyses11–14. While these studies provide important information on the timing of degeneration in this rabbit puncture model, rigorous quantitative outcomes, including MRI, biomechanics and micro-scale analyses, have not yet been performed. A more complete assessment across length scales can be used to define key relationships between structure and function in both healthy conditions and during IVD degeneration which, when validated in human degeneration, may aid in the development of novel diagnostic and treatment strategies.

To accomplish the goal of enhancing diagnostic techniques, we sought to correlate our quantitative outcomes with a non-invasive clinically relevant diagnostic modality, T2 MRI. Current clinical diagnostic tools are limited to plain radiographs and qualitative T2-weighted MRI, based on observational changes to signal intensity12,13. Both of these imaging modalities are insensitive to early degenerative IVD changes14. T2 mapping has the potential to aid in diagnosis by detecting early IVD disease and evaluating therapeutics15. T2 mapping correlates with biomechanical and biochemical outcomes in ex vivo and in vitro models16,17,18, yet correlation analyses for in vivo degeneration have not yet been conducted. Therefore, further characterization of the factors influencing T2 measurements with degeneration is necessary to advance this modality to a clinically relevant diagnostic tool.

The goal of the current study was to perform a quantitative analysis of the structural and functional alterations in the healthy and degenerating rabbit IVD, using emerging tools that enable assessment from the microscale to the macroscale. We utilized the rabbit AF puncture model and evaluated the compositional changes, through MRI, second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging, histology, biochemistry and immunochemistry, as well as mechanical changes across length scales using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and whole motion segment biomechanical testing. Given that it is not clear exactly where degeneration begins and that some of these outcomes can be applied at a very local level (i.e., within a given substructure of the disc), we also interrogated the time sequence of change in these localized regions. We hypothesize that macroscale mechanical properties will be most strongly correlated with quantitative imaging parameters. Insight into the qualitative effects associated with degeneration, and the correlation of quantitative parameters with MRI, could help inform new diagnostic grading tools and more effective intervention strategies for patients with back pain associated with IVD dysfunction.

Materials and methods:

Animal surgery:

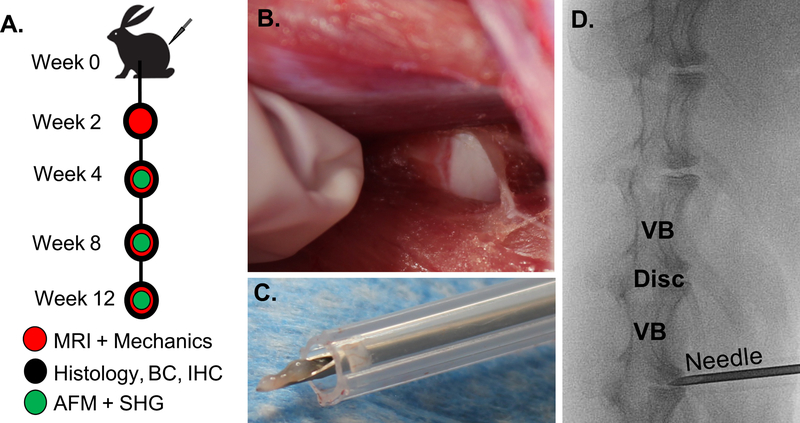

The study design and sample allocation are indicated in Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1. Fifteen New Zealand White male skeletally mature rabbits (~3kg, ~3 months of age) (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) underwent standard perioperative protocols for surgery at the University of Pennsylvania. The anesthesia protocol was defined by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee guidelines for rabbit surgery. A paramedian longitudinal skin incision was made, and dissection continued down through the intermuscular plane between the paraspinous and external abdominal oblique musculature. The plane was bluntly developed, and the peritoneum and abdominal contents were reflected ventrally. The ventrolateral vertebral bodies and IVDs from L2/3 to L6/7 were exposed and confirmed radiographically (Fig. 1B & D). A 16-gauge needle was inserted 5 mm into the anterior AF of discs L2/L3 through L6/L7 and rotated 360° To confirm adequate injury, NP material was visualized on the needle after each puncture (Fig. 1C). At post-operative week 2, 4, 8, and 12, rabbits were sacrificed, and lumbar motion segments without posterior elements (vertebral body–IVD–vertebral body) were isolated for analysis and stored at −20°C in PBS with protease inhibitors. All samples underwent MRI and were then divided for 1) whole motion segment biomechanical testing and AFM, 2) biochemistry, or 3) histology (Fig. 1A). Additional motion segments were harvested from healthy age-matched rabbits (Sierra Medical Science, Whittier, CA) to serve as experimental controls for each assay.

Figure 1.

A) Study design. Fifteen New Zealand White male rabbits underwent surgery to puncture four lumbar intervertebral discs (week 0). At 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks animals were sacrificed and motion segments were evaluated using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), mechanical testing, histology, biochemistry (BC), immunohistochemistry (IHC), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging. To puncture the discs, B) the lumbar disc space was exposed through a retroperitoneal approach. C) A 16-gauge needle was inserted into the anterior AF and turned 360 degrees, such that NP material was extruded. D) An intraoperative radiograph was performed to confirm vertebral level of injury (VB = vertebral body).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI):

MRI scans were performed at 4.7T (Magnex Scientific Limited, Abington, UK) on punctured motion segments (n=12–16 per time point) and control motion segments (n=10). Using a custom-made 17 mm diameter solenoid coil, a series of three mid-coronal slices for T2 mapping (TE=i*11.13ms, i=1,2…16, 195 mm in-plane resolution, 0.5 mm slice thickness) were obtained, and average T2 maps were generated using custom MATLAB software, as previously described19. The NP and AF regions were manually contoured from the T2 maps to calculate mean NP and AF T2.

Biomechanical testing:

Following MRI, samples were frozen until mechanical testing (n=5–6 per group per time point). After thawing, samples were potted in custom fixtures using low-melting temperature indium casting alloy (McMaster-Carr, Robbinsville, NJ). A biomechanical testing protocol consisting of 20 sawtooth cycles (19 cycles of preconditioning, 20th cycle used for analysis) of tension and compression (+21 N to −42N) at 0.5 Hz, followed by a 10-minute creep test at −42 N (~0.48 MPa), was performed as previously described16,20,21 (Instron 5948, Norwood, MA). All tests were performed at room temperature in a bath of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with protease inhibitors (SIGMAFAST Protease Inhibitor Tablets, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Optical tracking of displacement was performed using a high-resolution digital camera (A3800; Basler, Exton, PA) and a custom MATLAB texture tracking program16,21.

The optically measured force-displacement curves obtained from the 20th cycle of tension-compression were fit to a sigmoid function using a custom MATLAB program, from which neutral zone (NZ) modulus, NZ range of motion (ROM), compressive modulus, and compressive ROM were calculated, as previously described16,21. Time-dependent creep behavior from the optical displacement data was fit to a 5-parameter viscoelastic constitutive model to quantify time constants τ1 and τ2 and damping stiffness S1 and S216,21. For both creep and tension-compression, force-displacement data were normalized to disc height and axial area measured from the MRIs.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM):

Following macroscale biomechanical testing, motion segments (n=5–6 per group per time point) were equilibrated in PBS with protease inhibitors at room temperature for one hour, and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature media (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Motion segments were cryosectioned in the sagittal plane at 20µm thick using Kawamoto’s film method 22. After thawing in PBS with protease inhibitors, AFM-nanoindentation was performed on these sections using microspherical colloidal tips (R ≈ 12.5µm, nominal k ≈ 0.6N/m, Q:NSC36/Tipless/Cr-Au, cantilever C, NanoAndMore, Watsonville, CA) using a Dimension Icon AFM (BrukerNano, Santa Barbara, CA). Indentation was applied at a z-piezo displacement rate of 10µm/s to a maximum load of ≈ 120nN. For each microstructural region within the AF (inner AF, outer AF), indentation was performed on 3 12 different locations. At the same location, nanoindentation was repeated three times to ensure repeatability. The indentation modulus, Eind (MPa), at each location, was calculated by fitting the entire loading portion of each force-displacement curve to the finite thickness-corrected Hertz model, via least squares linear regression in MATLAB, as previously described23.

Biochemistry:

IVDs were dissected from the motion segment and manually separated into AF and NP portions (n=3–5 per group per time point). The AF and NP were individually digested overnight in proteinase K at 60°C. Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content of each region was determined using the dimethyl methylene blue dye binding assay (DMMB)24, and collagen content was quantified via the p-diaminobenzaldehyde/chloramine-T assay for ortho-hydroxyproline (OHP)25. GAG and collagen content were normalized to sample wet weight.

Histology:

Additional motion segments (n=3–4 punctured/time point, n=2 controls) were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich), decalcified (Formical 2000; StatLab, McKinney, TX), processed into paraffin, and sectioned at 10mm thick in the sagittal plane. Mid-sagittal sections were stained with Alcian blue and picrosirius red for proteoglycans and collagen, respectively, or hematoxylin and eosin. Stained sections were imaged at 20x using brightfield and polarized light microscopy (ZEISS Axio Scan.Z1, Oberkochen Germany and Nikon Eclipse Ni-E, Melville, NY).

Immunohistochemistry:

Immunohistochemistry was performed on additional mid-sagittal paraffin sections to detect the aggrecan neo-epitope, NITEGE (MD Biosciences, 1042003, Oakdale, MN), indicative of aggrecanase degradation. Rehydrated sections were serially incubated at room temperature in proteinase K (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 5 minutes, 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, horse serum for 30 minutes (Vectastain ABC Universal Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and primary antibody overnight at 4° C. Secondary visualization was performed using the Vectastain ABC Universal HRP Kit (PK-6200, Vector Laboratories, Burlinghame, CA) and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Statistical analysis:

Animal numbers were determined by a power analysis of previous data obtained by our group evaluating differences between MRI T2 values of healthy control rabbit discs and discs digested with chymopapain16, demonstrating an effect size of 30. Achieving a statistical power of 0.8 required four motion segments per group for quantitative outcomes. Statistical analyses of results were performed in Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA), with statistical significance defined as p<0.05. Graphically, data is represented as mean ± standard deviation. Outliers were removed from quantitative data based on p<0.05 using the Grubbs’ test. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was first performed, and then the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was used to determined significant differences in NP and AF T2 values, GAG and collagen content, mechanical properties, and AFM of the AF regions, for IVDs in the control, 2, 4, 8 and 12-week punctured groups. Upper and lower 95% confidence intervals (CI) of mean values are listed in the results section for the measurements that yielded statistical significance in the non-parametric analysis above. Correlation coefficients were calculated for all combinations of measured variables from the same sample, including MRI, macromechanics, and micromechanics, using R-software (http://www.r-project.org/). Correlation matrices of r and p values were generated for all combinations of quantitative measurements using the corrplot function. A forward step-wise multiple linear regression was then performed to develop a statistical model of the relationship between macroscale and microscale mechanics and NP and AF T2.

Results

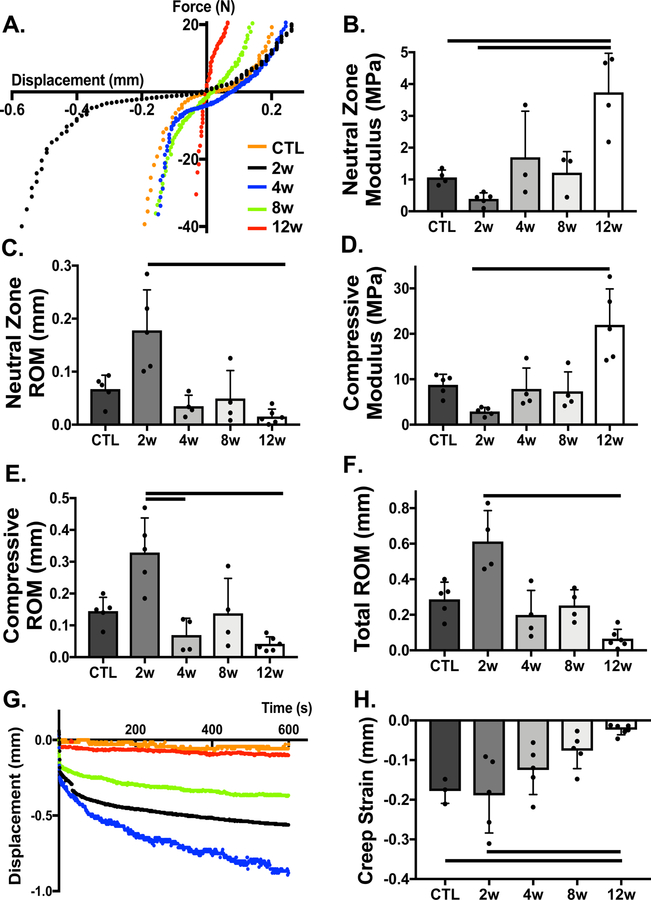

All animals survived surgery without complication and returned to normal cage activity. Following needle puncture of the IVD, degeneration was readily apparent via marked changes in whole disc structure and mechanics over time. Representative force-displacement and creep curves for each group, shown in Fig. 2A & G, demonstrate changes in whole disc mechanical function. Qualitatively, motion segments appeared to have increased ROM and reduced modulus at 2 weeks, followed by subsequent stiffening, compared to healthy controls (Fig. 2B–F). There was a statistically significant (p=0.0009) decrease (89%) in ROM from 2 weeks (95% CI: 0.335, 0.889 mm) to 12 weeks (95% CI: 0.010, 0.121 mm) (Fig. 2F). Creep strain followed a similar trend (Fig. 2G), with a statistically significant 89% reduction at 12 weeks (95% CI: −0.037, 0.009 mm) compared to the control (95% CI: −0.256, −0.100 mm) and 2 week (95% CI: −0.307, −0.071 mm) punctured groups (p=0.01, p=0.004, respectively) (Fig. 2H). At 12 weeks, the early (S1) (95% CI: 5.531, 59.630 MPa) and late (S2) (95% CI: 5.339, 48.120 MPa) creep moduli significantly increased (p=0.005 and p=0.1, respectively) relative to the 2 week group (S1 95% CI: [0.766, 6.676], S2 95% CI: [0.800, 3.116] MPa), and the creep time constants (τ1 and τ2) generally decreased over time, with statistically significant differences observed for τ2 between 8 weeks (95% CI: 108.900, 1569 s) and 12 weeks (95% CI: 10.180, 366.4 s) (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Macro mechanical properties of whole motion segments are altered with time following needle puncture. A) Representative force-displacement curves of motion segments in tension and compression, from which B) neutral zone modulus C) neutral zone range of motion (ROM), D) compressive modulus, E) compressive ROM, and F) total ROM were quantified each experimental group. G) Representative displacement over time curves for each experimental group under constant creep load for 10 minutes. H) Creep strain was quantified as the change in disc height from the beginning of creep to the end of test, normalized by disc height and axial area. Bars indicate statistical significance (p<0.05)

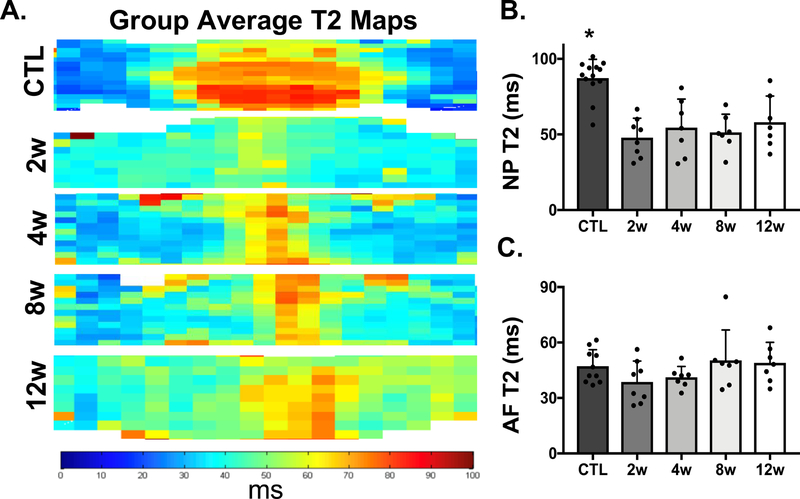

MRI T2 maps from each experimental group provided additional information with respect to the spatial distribution of T2 across the NP and AF regions of the IVD after needle puncture (Fig. 3A). After puncture, the boundary between the NP and AF became less distinct, and T2 values in the NP statistically significantly (p<0.04) decreased (43% change) at 2 weeks (95% CI: 46.75, 88.21 ms), 4 weeks (95% CI: 61.54, 89.05 ms), 8 weeks (95% CI: 42.57, 78.52 ms), and 12 weeks (95% CI: 49.21, 89.74 ms), compared to control NP values (95% CI: 96.94, 141.70 ms) (Fig. 3B). There were no statistically significant differences detectable in AF T2 at any time point compared to healthy controls.

Figure 3.

MRI evaluation of control (CTL) and experimental groups (2w-12w). A) Average T2 maps from the CTL and punctured groups. B) T2 values (ms) of the NP region of each sample in the CTL and punctured groups. Asterisks indicate significance (p<0.05) compared to all punctured groups. C) T2 values (ms) of the AF region of each sample in the CTL and punctured groups.

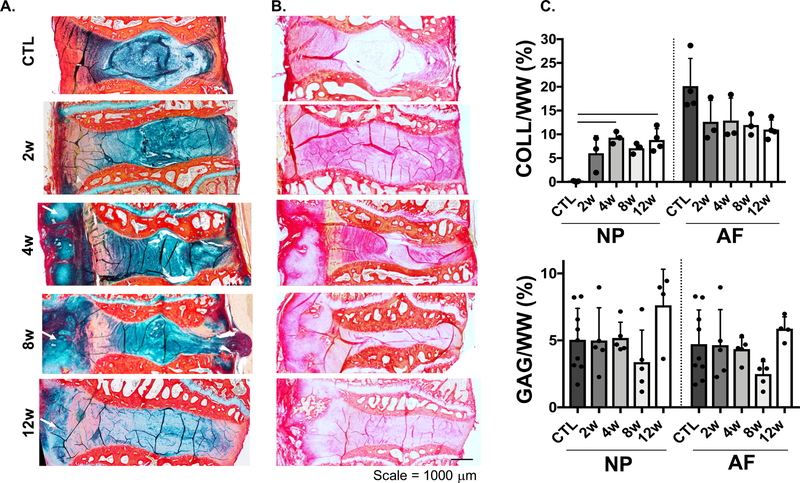

Histological analysis of motion segments at 4, 8 and 12 weeks post-puncture showed substantial anterior fibrotic remodeling and osteophyte formation at the location of puncture. There was also an overall reduction in disc height, general disorganization of the annular lamellar structure, condensation of the remaining NP matrix, and a posterior herniation in one animal into the spinal cord region (Fig. 4). Interestingly, a noticeable loss of proteoglycans was only noted at the latest time point (12 weeks), indicated by less Alcian blue staining throughout the remaining NP region (Fig. 4A). However, no significant differences in GAG content in the AF and NP were observed (Fig. 4C). With respect to collagen, there was a substantial increase in picrosirius red staining in the NP region in all punctured groups, compared to controls (Fig. 4B). This increase in NP staining corresponded to a statistically significant 98% (p<0.04) increase in collagen content at 4 weeks (95% CI: 4.288, 9.873 collagen/wet weight) and 12 weeks (95% CI: 5.022, 12.580 collagen/wet weight) relative to controls (95% CI: 0.0334, 0.223 collagen/wet weight) (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

A) Histology of the motion segments stained with alcian blue (GAG) and picrosirius red (collagen), B) picrosirius red staining, arrows indicate anterior fibrotic remodeling and osteophyte formation. C) Quantification of collagen and GAG content (% wet weight, WW) of the nucleus pulposus (NP) and annulus fibrosus (AF) regions, bars represent significance (p<0.05).

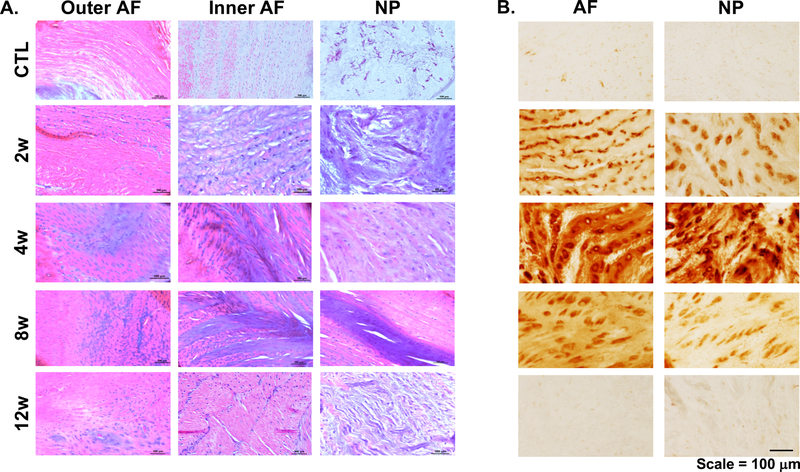

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections showed evidence that the inner AF had collapsed into the NP region, beginning at 2 weeks and continuing through 8 weeks (Fig. 5A), and that substantial condensation and fibrotic remodeling of the NP matrix had occurred as early as 2 weeks. Cellular morphology was also substantially altered following puncture, with cells in the AF region transitioning from an elongated shape to rounded morphology, and cells within the NP transitioning from a rounded shape to elongated morphology. Staining for NITEGE, an aggrecan C-terminal neo-epitope that is generated by aggrecanase-mediated proteolysis26, was absent in control and 12 week samples, but was elevated in intensity at 2, 4 and 8 weeks, with the most robust staining present at 4 weeks (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the outer and inner annulus fibrosis (AF) regions, and the nucleus pulposus (NP), B) immunohistochemistry for NITEGE of the AF and NP regions.

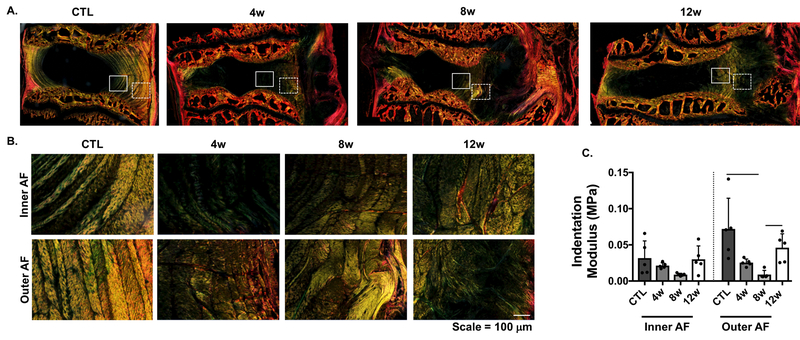

Polarized light microscopy revealed disorganization in the AF, with loss of lamellar structure in the inner AF as early as 2 weeks post-puncture. This initial disruption in lamellar organization progressed to total disorganization of both the inner and outer AF over time, and increased collagen deposition by 12 weeks (Fig. 6A & B). AFM analysis demonstrated a reduction in the indentation modulus (Eind) in both the inner and outer AF from 4 to 8 weeks compared to controls, consistent with these structural changes. At 8 weeks, Eind of the outer AF (95% CI: 0.002, 0.016 MPa) was statistically significantly (p=0.002) lower (88% change) than the same region of control samples (95% CI: 0.019, 0.125 MPa). Eind of the outer AF significantly (p=0.03) increased 80% from 8 to 12 weeks (95% CI: 0.022, 0.070 MPa)(Fig. 6C), suggestive of AF remodeling and potential scar tissue formation.

Figure 6.

A) Macroscopic view of polarized light microscopy, where the inner AF and outer AF are denoted by the solid and dashed rectangles, respectively. B) Higher magnification of the inner and outer AF regions in A, and corresponding C) indentation modulus of these regions using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Bars indicate statistical significance (p<0.05).

Correlations (Table 1) between quantitative outcome metrics (NP T2, AF T2, NZ modulus, compressive modulus, NZ ROM, compressive ROM, total ROM, inner AF Eind, outer AF Eind, and creep strain) demonstrated that all biomechanical outcomes were statistically significantly correlated with each other (p<0.01). Additionally, NP T2 significantly correlated with Eind of the inner (p=0.05) and outer (p<0.001) AF, and AF T2 trended towards correlation (p=0.1) with compressive modulus. A forward step-wise multiple regression identified a model for NP T2 and AF T2 that incorporated micro and macroscale biomechanical outcome parameters (Table S1). Outer (p=0.06) and inner (p=0.08) AF Eind, AF T2 (p=0.02), NZ modulus (p=0.004), compressive modulus (p=0.01), and NZ ROM (p=0.22) were included in the model for NP T2, yielding a multiple r2 of 0.68 (p=0.002) with the equation:

A similar analysis was performed to develop a model for AF T2. However, compressive modulus was the only parameter included in the model (p=0.10), with a multiple r2 value of 0.12.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients.

| AF T2 | NZ Modulus | Compressive Modulus | NZ ROM | Compressive ROM | Total ROM | Eind – Inner AF | Eind – Outer AF | Creep Strain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP T2 | 0.26 | −0.17 | 0.19 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.17 | 0.40* | 0.58** | −0.12 |

| AF T2 | 0.26 | 0.35* | −0.22 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.08 | 0.33 | |

| NZ Modulus | 0.67** | −0.46** | −0.54** | 0.56** | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.48** | ||

| Compressive Modulus | −0.59 | 0.65 | −0.72** | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.59** | |||

| NZ ROM | 0.89 | 0.81** | −0.33 | −0.13 | −0.66** | ||||

| Compressive ROM | 0.91** | −0.33 | −0.07 | −0.61** | |||||

| Total ROM | −0.32 | −0.11 | −0.55** | ||||||

| Eind – Inner AF | 0.66** | −0.03 | |||||||

| Eind – Outer AF | −0.23 |

= p<0.05

= p<0.1

Discussion

In this study, we utilized a rabbit AF injury model to define the time sequence of alterations in disc structure-function relationships during degeneration, and to correlate degeneration severity with clinical imaging parameters. To our knowledge, this is the first study to probe the local micromechanics of the disc in an in vivo degeneration model, and subsequently correlate these microscale properties with MRI. This work builds on previous studies which have demonstrated reproducible degeneration after annular puncture in the rabbit, evaluated through radiographic disc height changes27,10, loss of MRI signal intensity28, T219 in the NP, a decrease of macroscale dynamic modulus27, and histologic alterations10. These previous studies attributed degenerative functional changes in the IVD to fibrotic remodeling of the NP tissue itself.

Our work supports these previous findings and provides further insight into the origin of ‘NP’ remodeling. Consistent with previous work, starting at 2 weeks post-puncture, progressive degeneration of the IVD occurred, characterized by structural and mechanical alterations across length scales. While NP T2 was reduced at 2 weeks post-puncture, suggestive of reduced water and proteoglycan content16,29, quantification of GAG content did not show significant changes over time. However, NITEGE staining indicated that NP aggrecan was fragmented due to the proteolytic activity of aggrecanase as early as 4 weeks. Therefore, although GAG content remained unchanged over time, aggrecan in the NP lost its normal molecular organization and structural integrity during degradation, thereby affecting water retention30,31. This could contribute to the alterations to NP T2 and disc mechanics, despite the absence of detectable changes in GAG content16.

The reductions in NP T2 that we noted are suggestive of NP fibrosis, supportive of the accepted mechanism of degeneration in this model. However, our histological data demonstrated at 4 weeks post-puncture, that the morphology and proliferation of cells within the NP resembled that of cells normally found in the AF, and that the NP matrix itself structurally resembled AF lamellae (Fig. 5A). This observation supports a new mechanism of degeneration in this model, where IVD degeneration in response to needle puncture is precipitated by the inner AF collapsing into the NP region. This AF collapse is then followed by remodeling, in an attempt to restore mechanics, due to the loss of pre-stress from the original hydrostatic stress of the native NP region. This local healing response has been documented in a mouse degeneration model32,33, where the cells in the native NP region proliferate and produce excessive extracellular matrix constituents, particularly type II collagen and aggrecan. As the rabbit annular puncture model is commonly used for the evaluation of regenerative therapeutics27,28,34, treatment strategies that fail to address this initial acute infolding of the AF may have poor efficacy in this particular model. A treatment that restores NP pressurization and AF structure such as a combined hydrogel injection35 and annular patch36, and does so very quickly after NP depressurization, may prove to be most efficacious in this model of degeneration.

Structural degeneration of the IVD was also associated with alterations in disc mechanical function across length scales. In the short term, we observed a drastic alteration in macroscale mechanical function, such that punctured discs initially had increased range of motion and decreased modulus, likely due to the acute severing of AF connectivity due to the needle puncture itself. Indeed, we observed similar mechanical changes to the IVD when motion segments were punctured in an ex vivo setting and then immediately subjected to mechanical testing (Fig. S3). As degeneration progressed, we observed whole motion segment stiffening at the macroscale from 4 to 12 weeks. This was at least in part dictated by the formation of anterior bridging osteophytes, which were observed in all motion segments at time points beyond 4 weeks (Fig. 4). Because the macroscale mechanical response of the disc was likely governed by the anterior osteophytes present at later time points, we also utilized AFM to probe changes to the local mechanical properties within the disc over the time course of degeneration.

At 4 weeks, Eind decreased relative to controls, yet by 8 and 12 weeks following puncture, this microscale mechanical measure of both the inner and outer AF appeared to recover to control levels. Polarized light and SHG imaging demonstrated progressive loss of the lamellar architecture and remodeling of the AF over time post-puncture. (Fig. 6 and Fig. S4). This ‘restored’ mechanics, but persistent altered structural organization, has been previously reported with needle puncture injury in a mouse model32, suggesting that attempted repair of the AF following needle puncture includes accelerated deposition of collagenous, disorganized, matrix, indicative of a fibrotic scarring response. However, despite the increase in Eind at 12 weeks, the pronounced alteration in the structure and composition of the NP indicates that the NP may lose its critical mechanical function of shock absorption between vertebrae, which is largely endowed by the highly negatively-charged aggrecan molecules37.

In order to facilitate the non-invasive detection of these multi-scale alterations with degeneration, we correlated quantitative MRI parameters with measures of disc function. The correlation matrix data demonstrated that NP T2 was statistically significantly correlated with the outer AF Eind, measured via AFM, contrary to our original hypothesis that macroscale mechanical properties would significantly correlate with T2. This discrepancy is likely due to the fact that the macroscale mechanics were predominantly dictated by the anterior bridging osteophytes; MRI was intended to measure disc space changes, not peripheral structures. However, multiple regression generated a model including both micromechanical and macroscale mechanical outcomes, highlighting the multifactorial nature of T2 relaxation in the degenerating disc. Nevertheless, upon further investigation in human discs, quantitative MRI may provide a useful tool to both locally and non-invasively assess changes to disc mechanics that occur with degeneration or regeneration.

In humans, disc degeneration is a complex and multifactorial process. Our data show that this rabbit AF puncture model recapitulates some, but not all, aspects of the human disease. The loss of AF organization, progressive fibrosis of the NP region, and alterations in whole disc mechanics seen in this rabbit model are also classically observed in human degeneration. Anterior osteophyte formation is also observed concomitant with disc degeneration in human patients, but usually not as early in disease onset as we have observed in this model8,38. In humans and animal models, degeneration of a single motion segment is associated with degenerative changes in adjacent discs39,40. Due to our study design, we were unable to assess these effects, but could utilize the rabbit puncture model to examine this in future studies, with puncture performed at a single level. Nevertheless, similar structure-function alterations likely occur in both the rabbit model and human degeneration41. Here, we demonstrate that MRI can be used to non-invasively determine the severity of these mechanical changes to the disc. This imaging modality, particularly when applied with high resolution scanning and validated in human patients, may facilitate improved diagnostics for early stage disc degeneration, provide insight into optimizing appropriate treatments for varying degrees of disc degeneration, and the capacity to longitudinally assess response to therapies.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Allocation of animals and motion segments to outcome assays.

Supplemental Figure 2. Biomechanics of the A) early (S1) and B) late (S2) creep moduli and the creep time constants C) τ1 and D) τ2. Bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Supplemental Figure 3. A) T2 maps of control (CTL), the ex vivo acute punctured and 2 week in vivo punctured groups, B) NP T2 quantification, C-F) macroscale biomechanics and G) AFM indentation modulus. Bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Supplemental Figure 4. Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of the inner and outer AF regions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Nathaniel Dyment at the University of Pennsylvania for providing the polarized light images. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (F30AG060670), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (F32AR072478-01), the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (NIH, P30 AR069619), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (IK1 RX002445, IK2 RX001476, I01 RX001321, AND I01 RX002274).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors have no competing interests or financial/personal relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Bonnevie ED & Mauck RL Physiology and Engineering of the Graded Interfaces of Musculoskeletal Junctions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 20, 403–429 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts S Disc morphology in health and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans 30, 864–869 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith LJ & Fazzalari NL The elastic fibre network of the human lumbar anulus fibrosus: architecture, mechanical function and potential role in the progression of intervertebral disc degeneration. Eur. Spine J 18, 439–448 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humzah MD & Soames RW Human intervertebral disc: structure and function. Anat. Rec 220, 337–56 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker MH & Anderson DG Molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. Off. J. North Am. Spine Soc 4, 158S–166S (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urban JPG & Roberts S Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res. Ther 5, 120–30 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boxberger JI, Orlansky AS, Sen S & Elliott DM Reduced nucleus pulposus glycosaminoglycan content alters intervertebral disc dynamic viscoelastic mechanics. J. Biomech 42, 1941–1946 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haefeli M et al. The course of macroscopic degeneration in the human lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine 31, 1522–31 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray CJL & Lopez AD Measuring the global burden of disease. N. Engl. J. Med 369, 448–457 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuda K et al. A novel rabbit model of mild, reproducible disc degeneration by an anulus needle puncture: correlation between the degree of disc injury and radiological and histological appearances of disc degeneration. Spine 30, 5–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobajima S et al. A slowly progressive and reproducible animal model of intervertebral disc degeneration characterized by MRI, X-ray, and histology. Spine 30, 15–24 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ & Wiesel SW Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 72, 403–408 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J & Boos N Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 26, 1873–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urban JPG & Winlove CP Pathophysiology of the intervertebral disc and the challenges for MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 25, 419–432 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry J et al. The value of T2 relaxation times to characterize lumbar intervertebral disks: preliminary results. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol 27, 337–342 (2006). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gullbrand SE et al. Correlations between quantitative T 2 and T 1 ρ MRI, mechanical properties and biochemical composition in a rabbit lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration model. J. Orthop. Res 34, 1382–1388 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoniou J et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of degenerative disc disease. Magn. Reson. Med 40, 900–907 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoniou J et al. Analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and biomechanical parameters on human discs with different grades of degeneration. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 38, 1402–1414 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin JT et al. Population average T2 MRI maps reveal quantitative regional transformations in the degenerating rabbit intervertebral disc that vary by lumbar level. J. Orthop. Res 33, 140–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connell GD, Jacobs NT, Sen S, Vresilovic EJ & Elliott DM Axial creep loading and unloaded recovery of the human intervertebral disc and the effect of degeneration. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 4, 933–42 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin JT et al. Needle puncture injury causes acute and long-term mechanical deficiency in a mouse model of intervertebral disc degeneration. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc 31, 1276–82 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamoto T & Shimizu M A method for preparing whole-body sections suitable for autoradiographic, histological and histochemical studies. Stain Technol 61, 169–83 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q et al. Micromechanical anisotropy and heterogeneity of the meniscus extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater 54, 356–366 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hukins DW A simple model for the function of proteoglycans and collagen in the response to compression of the intervertebral disc. Proc. Biol. Sci 249, 281–5 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy GK & Enwemeka CS A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clin. Biochem 29, 225–229 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lark MW et al. Cell-mediated catabolism of aggrecan. Evidence that cleavage at the ‘aggrecanase’ site (Glu373-Ala374) is a primary event in proteolysis of the interglobular domain. J. Biol. Chem 270, 2550–2556 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto K et al. Intradiscal injections of osteogenic protein-1 restore the viscoelastic properties of degenerated intervertebral discs. Spine J 6, 692–703 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aoki Y et al. Nerve fiber ingrowth into scar tissue formed following nucleus pulposus extrusion in the rabbit anular-puncture disc degeneration model: effects of depth of puncture. Spine 31, E774–780 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piazza M et al. Quantitative MRI correlates with histological grade in a percutaneous needle injury mouse model of disc degeneration. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc (2018). doi: 10.1002/jor.24028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Roughley PJ Biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration: involvement of the extracellular matrix. Spine 29, 2691–2699 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roughley PJ & Mort JS Analysis of aggrecan catabolism by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 836, 219–237 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torre OM, Das R, Berenblum RE, Huang AH & Iatridis JC Neonatal mouse intervertebral discs heal with restored function following herniation injury. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol 32, 4753–4762 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y et al. Early onset of disc degeneration in SM/J mice is associated with changes in ion transport systems and fibrotic events. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol 70, 123–139 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyazaki S et al. ISSLS PRIZE IN BASIC SCIENCE 2018: Growth differentiation factor-6 attenuated pro-inflammatory molecular changes in the rabbit anular-puncture model and degenerated disc-induced pain generation in the rat xenograft radiculopathy model. Eur. Spine J 27, 739–751 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gullbrand SE et al. Translation of an injectable triple-interpenetrating-network hydrogel for intervertebral disc regeneration in a goat model. Acta Biomater 60, 201–209 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz MA et al. Cell-Seeded Adhesive Biomaterial for Repair of Annulus Fibrosus Defects in Intervertebral Discs. Tissue Eng. Part A 24, 187–198 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nia HT et al. High-bandwidth AFM-based rheology reveals that cartilage is most sensitive to high loading rates at early stages of impairment. Biophys. J 104, 1529–1537 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernick S & Cailliet R Vertebral end-plate changes with aging of human vertebrae. Spine 7, 97–102 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frick SL, Hanley EN, Meyer RA, Ramp WK & Chapman TM Lumbar intervertebral disc transfer. A canine study. Spine 19, 1826–1834; discussion 1834–1835 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee CK Accelerated degeneration of the segment adjacent to a lumbar fusion. Spine 13, 375–377 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berg-Johansen B, Fields AJ, Liebenberg EC, Li A & Lotz JC Structure-Function Relationships at the Human Spinal Disc-Vertebra Interface. J. Orthop. Res doi: 10.10, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Allocation of animals and motion segments to outcome assays.

Supplemental Figure 2. Biomechanics of the A) early (S1) and B) late (S2) creep moduli and the creep time constants C) τ1 and D) τ2. Bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Supplemental Figure 3. A) T2 maps of control (CTL), the ex vivo acute punctured and 2 week in vivo punctured groups, B) NP T2 quantification, C-F) macroscale biomechanics and G) AFM indentation modulus. Bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Supplemental Figure 4. Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of the inner and outer AF regions.