Abstract

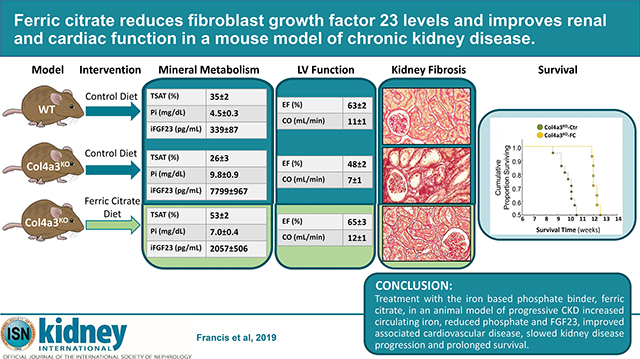

Iron deficiency, anemia, hyperphosphatemia, and increased fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) are common and interrelated complications of chronic kidney disease (CKD) that are linked to CKD progression, cardiovascular disease and death. Ferric citrate is an oral phosphate binder that decreases dietary phosphate absorption and serum FGF23 concentrations while increasing iron stores and hemoglobin in patients with CKD. Here we compared the effects of ferric citrate administration versus a mineral sufficient control diet using the Col4a3 knockout mouse model of progressive CKD and age-matched wild-type mice. Ferric citrate was given to knockout mice for four weeks beginning at six weeks of age when they had overt CKD, or for six weeks beginning at four weeks of age when they had early CKD. Ten-week-old knockout mice on the control diet showed overt iron deficiency, anemia, hyperphosphatemia, increased serum FGF23, hypertension, decreased kidney function, and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Ferric citrate rescued iron deficiency and anemia in knockout mice regardless of the timing of treatment initiation. Circulating levels and bone expression of FGF23 were reduced in knockout mice given ferric citrate with more pronounced reductions observed when ferric citrate was initiated in early CKD. Ferric citrate decreased serum phosphate only when it was initiated in early CKD. While ferric citrate mitigated systolic dysfunction in knockout mice regardless of timing of treatment initiation, early initiation of ferric citrate also reduced renal fibrosis and proteinuria, improved kidney function, and prolonged lifespan. Thus, initiation of ferric citrate treatment early in the course of murine CKD lowered FGF23, slowed CKD progression, improved cardiac function and significantly improved survival.

Keywords: Anemia, Phosphate Binder, Chronic Kidney Disease, Phosphate, FGF23, Cardiac Disease

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

FGF23 is an endocrine hormone that is secreted by osteocytes in response to high phosphate diets and states of impaired phosphate excretion, such as CKD. Under physiologic conditions, FGF23 stimulates phosphaturia and suppresses 1,25(OH)2D levels, thereby maintaining normal phosphate homeostasis 1–3. Although this compensatory response is initially adaptive, in the context of CKD, excess FGF23 leads to calcitriol deficiency that contributes to secondary hyperparathyroidism 3. Excess FGF23 levels are also powerful predictors of CKD progression, cardiovascular disease and death, suggesting that in addition to its classical role in regulating bone and mineral metabolism, markedly elevated FGF23 levels in CKD may have additional effects that directly contribute to these adverse outcomes 4–10. In support of this, FGF23 excess was shown to have a pathogenic role in development of cardiac hypertrophy 11–13 and dampening of host defenses in animal models of CKD 14, 15.

Ideal therapeutic approaches to reduce FGF23 in order to attenuate its potential adverse effects must lower FGF23 without sacrificing normal regulation of phosphate homeostasis because complete removal of FGF23 via administration of anti-FGF23 antibodies precipitates severe hyperphosphatemia that results in diffuse arterial calcification and early mortality 16. However, current approaches to lower FGF23 by reducing phosphate, such as dietary phosphate restriction or administering drugs that reduce gastrointestinal phosphate absorption, have had inconsistent effects in clinical trials 17, 18. This underscores the need to develop novel approaches to reduce FGF23 in patients with CKD.

Disordered iron homeostasis and anemia are also nearly universal clinical features of progressive CKD that develop early in the course of CKD 19. A link between iron metabolism and FGF23 regulation was first reported in 2011 in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) due to activating FGF23 mutations that impair its proteolytic cleavage 20–22. In normal patients and mice, iron deficiency increases FGF23 production, but this was associated with increased proteolytic cleavage to yield FGF23 cleavage fragments that have not been shown to have biologic activity in bone and mineral metabolism 20–22. In ADHR, iron deficiency increases circulating biologically active intact FGF23 (iFGF23) because the newly produced FGF23 cannot be cleaved. This results in hypophosphatemia, vitamin D deficiency, rickets and osteomalacia 20–22. Notably, CKD appears to be analogous to ADHR in that it leads to a state of impaired FGF23 cleavage 23, 24. We and others recently demonstrated that functional iron deficiency, inflammation, and erythropoietin all increase production of FGF23 and FGF23 cleavage, except in conditions that impair FGF23 cleavage, such as CKD, in which these stimuli increased biologically active iFGF23 24–27.

Ferric citrate (Auryxia, Akebia Therapeutics Inc, Boston, MA, USA) was FDA-approved in the United States in 2014 for treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with CKD receiving dialysis and for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in CKD patients not yet on dialysis. Ferric citrate has shown promise in several studies to correct iron deficiency anemia and hyperphosphatemia and lower FGF23 levels in CKD patients 28–30. Since ferric citrate is uniquely positioned among the phosphate binders to lower FGF23 levels through two independent mechanisms by simultaneously correcting iron deficiency and also binding to dietary phosphate, we tested the hypotheses that ferric citrate treatment will reduce FGF23 and mitigate negative outcomes in the Col4a3KO mouse model of progressive CKD.

Results

Col4a3KO mouse model of CKD

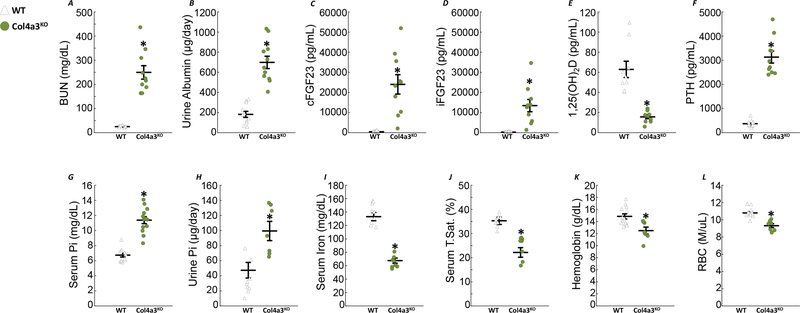

BUN and urinary albumin excretion were all significantly elevated in 9–10-week-old Col4a3KO compared to wild-type (WT) mice fed standard chow (Fig1A–B). As previously published 31–33, circulating total FGF23, measured by a C-terminal assay (cFGF23), and intact FGF23 (iFGF23), were dramatically increased in Col4a3KO compared to WT mice (Fig1C–D). Col4a3KO mice also showed increased PTH and reductions in 1,25(OH)2D together with increased serum phosphate and urinary phosphate excretion compared to WT (Fig1E–H). Systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure (BP) were elevated in CKD mice compared to age-matched WT controls (Table 1). Finally, Col4a3KO mice showed reduced levels of serum iron, transferrin saturation (TSAT), hemoglobin (Hb) and red blood cell (RBC) counts (Fig1I–L), demonstrating that iron absorption and transport are impaired and are accompanied by anemia of CKD.

Figure 1: Col4a3KO mice: a model of chronic kidney disease with anemia.

Levels of serum BUN (A), urine albumin (B), serum cFGF23 (C), serum iFGF23 (D), serum 1,25(OH)2D (E), serum PTH (F), serum phosphate (G), urine phosphate (H), serum iron (I), serum transferrin saturation (J), hemoglobin (K) and red blood cell number (L) in 9–10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a standard diet. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥11 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice.

Table 1:

Elevated BP in Col4a3KO mice.

| WT | Col4a3KO | |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 139±3 | 170±7* |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 100±3 | 123±6* |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 112±3 | 138±6* |

Non-invasive systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure (BP). Values are Mean ± SE, n≥13 per group

p<0.05 vs. WT.

Ferric citrate supplementation in mice with moderately advanced CKD reverses IDA

To investigate whether ferric citrate (FC) treatment can correct FGF23 elevations in Col4a3KO mice, we first determined the optimal percentage of FC to be added to the food. We fed 8 week-old Col4a3KO animals escalating doses of FC for one week (SFig1) and found that 5% FC supplementation is sufficient to reduce levels of cFGF23.

To further study the long-term impact of FC on FGF23 production, we conducted two different experimental protocols in which we treated Col4a3KO mice with either early stage CKD (4-week-old mice) or overt CKD (6-week-old mice) a mineral sufficient control (Ctr) or a 5% FC diet versus age-matched WT mice. We collected all mice at 10 weeks of age for detailed investigation.

Six-week-old Col4a3KO mice already show signs of impaired kidney function, evidenced by increased BUN and urine albumin excretion (Fig2A&B). Total and intact FGF23 were also slightly elevated in the Col4a3KO mice (Fig2C&D). However, no changes were observed in phosphorus (Fig2E&F), 1,25(OH)2D or PTH levels at this stage (data not shown). Circulating levels of iron, TSAT, Hb and RBC were similar in WT and Col4a3KO mice, indicating that development of anemia occurs later in the course of CKD (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2: FGF23 increase is an early event during CKD progression.

Levels of serum BUN (A), urine albumin (B), serum cFGF23 (C), serum iFGF23 (D), serum phosphate (E), urine phosphate (F) in 6 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a standard diet. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥11 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice.

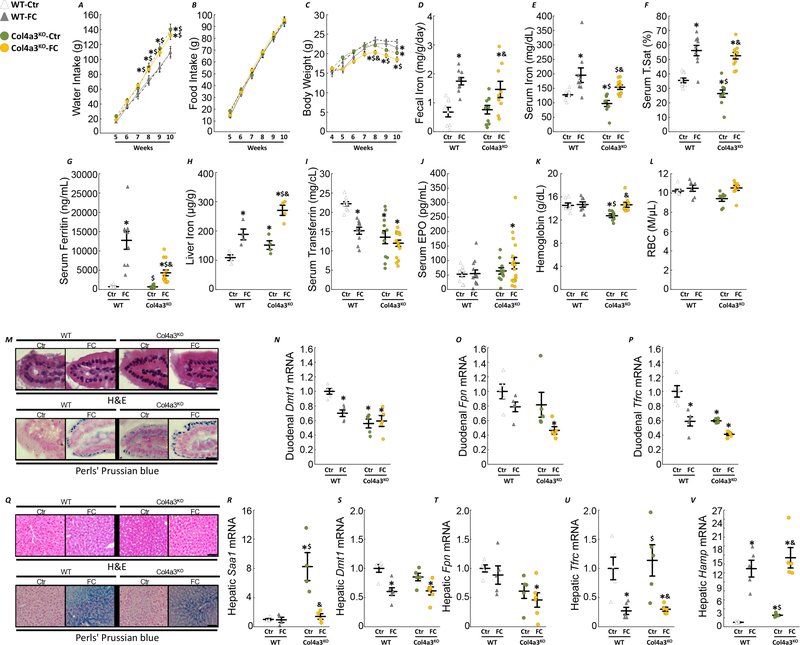

Col4a3KO mice fed the control diet (Col4a3KO-Ctr) had a significantly higher water intake and lower food intake (Fig3A–C) at the end of the study and consequently weighed less than diet matched WT mice (WT-Ctr). Four weeks of ferric citrate supplementation did not alter the water and food intake, and body weight was similar in FC compared to Ctr mice. As expected, FC supplementation increased fecal iron in both WT and CKD mice, compared to their respective controls (Fig3D).

Figure 3: Ferric citrate administration in mice with moderate CKD improves iron deficiency.

Longitudinal measurements of cumulative (A) water intake, (B) food intake and body weight (C). Levels of fecal iron (D), serum iron (E), serum transferrin saturation (F), serum ferritin (G), serum transferrin (H), serum erythropoietin (I), hemoglobin (J) and red blood cell number (K) in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 4 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice.

Col4a3KO-Ctr mice showed decreased serum iron and TSAT in parallel with decreased Hb and RBC (Fig3E–K). FC administration restored serum iron, TSAT and EPO and increased serum ferritin in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig3E–G). As a likely consequence of increased circulating iron and increased EPO levels, Col4a3KO-FC mice showed higher levels of Hb and RBC compared to Col4a3KO-Ctr mice (Fig3J–K).

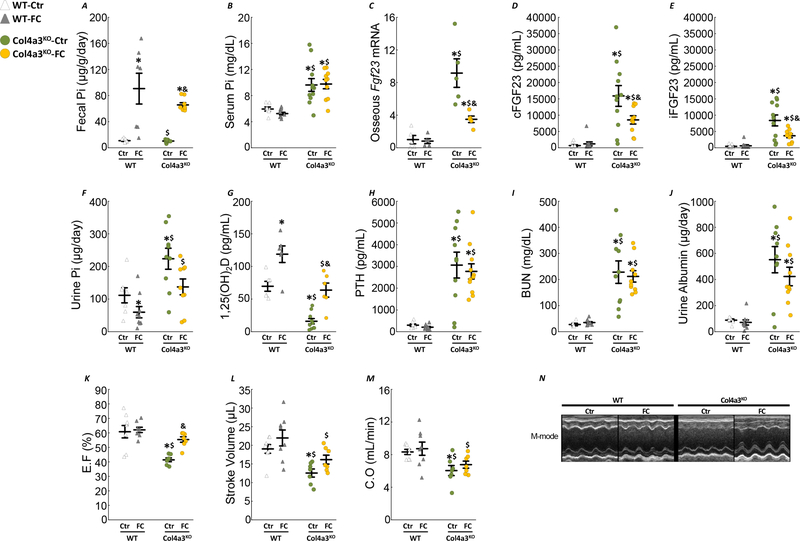

Effects of ferric citrate administration to mice with moderately advanced CKD on mineral metabolism

Despite the reduction in phosphate absorption, FC did not reduce circulating phosphate levels (Fig4A–B) and had no impact on serum calcium levels (SFig2). However, FC administration significantly reduced bone Fgf23 expression, cFGF23 and iFGF23 levels in Col4a3KO mice (Fig4C–E). The combined reduction of phosphate absorption and iFGF23 levels contributed to reduced urinary phosphate excretion in both WT and Col4a3KO mice (Fig4F). FC supplementation increased 1,25(OH)2D levels in WT and Col4a3KO mice, but did not change PTH (Fig4G&H). In addition, FC supplementation did not correct the levels of BUN and albuminuria in Col4a3KO mice (Fig4I&J). Finally, Col4a3KO-Ctr mice displayed increased BP (Table2) and systolic dysfunction, as previously reported 33 and evidenced by reduced ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume and cardiac output (CO) (Fig4K–N). Interestingly, FC administration corrected BP and EF in Col4a3KO-FC mice. Taken together, these results suggest that FC administration to Col4a3KO mice with moderately advanced CKD is able to prevent the dramatic increase in FGF23, hypertension and cardiac disease but does not delay CKD progression.

Figure 4: Ferric citrate administration in mice with moderate CKD reduces FGF23 production.

Levels of fecal phosphate (A), serum phosphate (B), bone Fgf23 expression (C), serum cFGF23 (D), serum iFGF23 (E), urine phosphate (F), serum 1,25(OH)2D (G), serum PTH (H), serum BUN (I) and urine albumin (J). Echocardiography analysis of left ventricular ejection fraction (K), stroke volume (L), cardiac output (M) and representative M-mode echocardiography (N). Measurements performed in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 4 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice.

Table 2:

Administration of ferric citrate corrects blood pressure increase in Col4a3KO mice with moderate CKD.

| WT | Col4a3KO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctr | FC | Ctr | FC | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 142±5 | 145±4 | 165±6*$ | 150±4& |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 104±3 | 106±4 | 124±6*$ | 108±5& |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 117±3 | 119±4 | 137±6*$ | 122±4& |

Non-invasive systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure (BP) in 10-week old animals. Values are Mean ± SE, n≥11 per group, p<0.05 vs.

WT-Ctr

WT-FC

Col4a3KO-Ctr mice.

Effects of ferric citrate administration to mice with early CKD

Given the salutary effects of FC treatment on FGF23 and anemia in 6 week-old Col4a3KO mice, we hypothesized that initiating FC in younger mice, before the onset of advanced CKD, could also have beneficial effects on kidney disease. To study the long-term impact of FC, we fed 4 week-old WT and Col4a3KO mice, a mineral sufficient control (Ctr) or a 5% Ferric Citrate enriched (FC) diet for 6 weeks. As in the prior experiment, FC supplementation had no major effect on water and food intake in mice, although CKD animals fed a FC diet weighed less by the end of the experiment compared to age-matched untreated CKD mice (Fig5A–C). Likewise, FC increased iron absorption in both WT and Col4a3KO mice, as evidenced by increased serum iron, TSAT, ferritin levels and liver iron content (Fig5E–L), and restored Hb levels in Col4a3KO mice. Increased absorption of iron triggered an increase in duodenal iron retention in both WT and Col4a3KO mice, shown by increased iron staining in duodenal microvilli (Fig5M). Of note, Col4a3KO-Ctr mice display abnormally reduced expression levels of the iron transport genes, divalent metal transporter 1 (Dmt1) and transferrin receptor (Tfrc), indicating impaired iron absorption (Fig5N–P). Iron supplementation led to an increase in hepatic iron staining in both FC-fed WT and Col4a3KO mice (Fig5Q), decreased inflammatory burden (Fig5R) coupled to a similar reduction in hepatic Dmt1, Fpn and Tfrc (Fig5S–U). Finally, FC diet increased hepatic expression of the iron regulatory protein hepcidin (Hamp), in WT-FC mice, and further increased Hamp expression in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig5S–V).

Figure 5: Ferric citrate administration in mice with early CKD corrects anemia of CKD.

Longitudinal measurements of cumulative (A) water intake, (B) food intake and body weight (C). Levels of fecal iron (D), serum iron (E), serum transferrin saturation (F), serum ferritin (G), liver iron (H), serum transferrin (I), serum erythropoietin (J), hemoglobin (K) and red blood cell number (L) in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group. Representative sections of duodenal microvilli stained with hematoxylin & eosin or Perls’ Prussian blue iron staining (M, bar=15 μm) and mRNA expression of markers of iron metabolism in duodenum, Dmt1 (N), Fpn (O) and Tfrc (P). Representative sections of liver stained with hematoxylin & eosin or Perls’ Prussian blue iron staining (Q, bar=50 μm) and hepatic mRNA expression of inflammatory marker Saa1 (R) and of markers of iron metabolism, Dmt1 (S), Fpn (T), Tfrc (U) and Hamp (V). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥4 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. Measurements performed in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks.

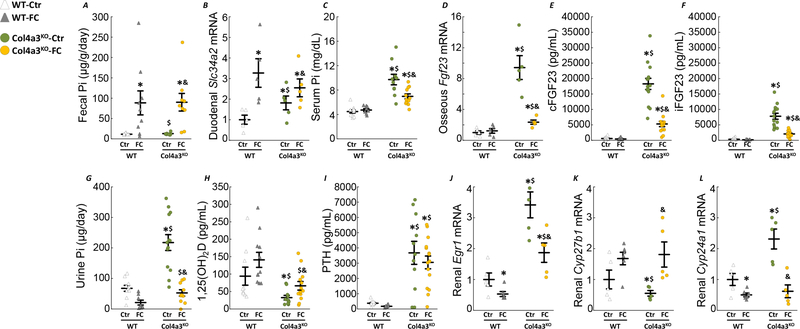

Ferric citrate supplementation in early CKD reduces phosphate and FGF23 levels

FC supplementation significantly reduced phosphate absorption in both WT-FC and Col4a3KO-FC mice, as shown by an increase in fecal phosphate and an increase in duodenal isoform of sodium-phosphate cotransporter solute carrier 34 A 2 (Slc34a2, Npt2b; Fig6A&B). The longer 6-week exposure to FC also reduced serum phosphate, and further reduced FGF23 bone expression and circulating levels in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig6C–F), likely due to the combined increase in circulating iron levels and serum phosphate reduction. Reductions in serum FGF23 and phosphate contributed to a dramatic decrease in urinary phosphate excretion (Fig6G). FC administration restored 1,25(OH)2D levels in Col4a3KO-FC mice, likely due to FGF23 reduction, but did not modify CKD associated hyperparathyroidism (Fig6H–I). Increased renal FGF23 signaling in CKD is evidenced by increased mRNA expression of early growth response protein 1 (Egr1) in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice, suppression of the vitamin D anabolic enzyme (Cyp27b1) and stimulation of vitamin D catabolic enzyme (Cyp24a1) (Fig6J–L). In line with our findings, FC supplementation reduced Egr1 in Col4a3KO-FC mice, and restored Cyp27b1 and Cyp24a1 expression.

Figure 6: Ferric citrate administration in mice with early CKD decreases FGF23 production.

Levels of fecal phosphate (A), duodenal slc34a2 (B), serum phosphate (C), osseous Fgf23 mRNA expression (D), serum cFGF23 (E), serum iFGF23 (F), urine phosphate (G), serum 1,25(OH)2D (H) and serum PTH (I) in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. Renal mRNA expression of FGF23 targets, Egr1 (J), Cyp27b1 (K), Cyp24a1 (L). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥5 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. Measurements performed in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks.

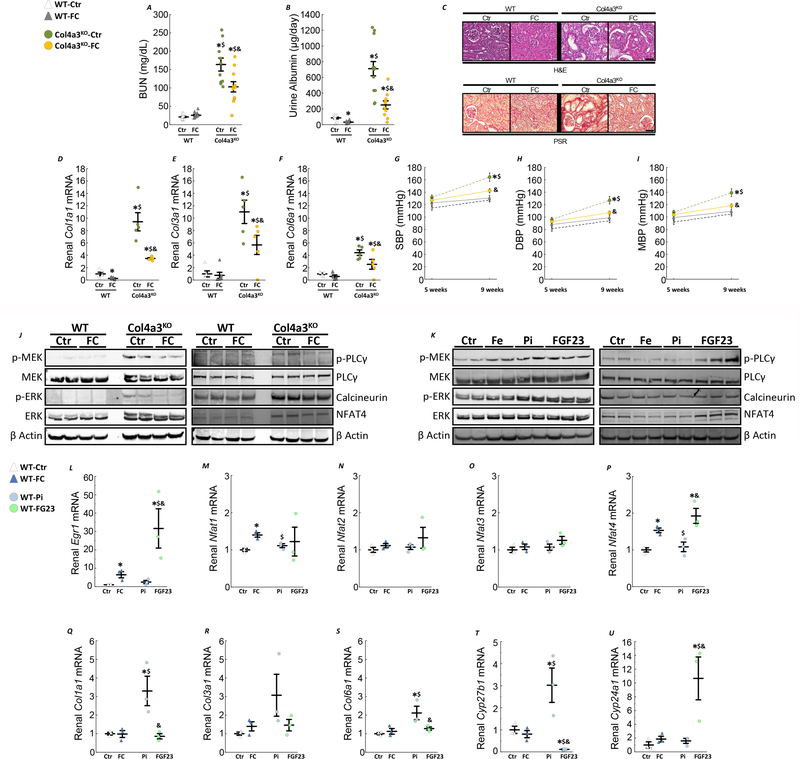

Ferric citrate supplementation in early CKD delays CKD progression and prevents hypertension

In association with improved iron status and reduced circulating phosphate and FGF23 levels, Col4a3KO-FC mice unexpectedly showed improved kidney function after 6 weeks of FC supplementation, evidenced by reduced BUN and albuminuria (Fig7A&B), suggesting that early delivery of FC slowed progression of kidney disease. Reductions in interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy were also evident by histology in Col4a3KO-FC animals compared to Col4a3KO-Ctr group (Fig7C). FC administration significantly reduced kidney expression of several collagen isoforms Col1a1, Col3a1 and Col6a1 in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig7D–F), which are associated with renal fibrosis and were highly elevated in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. In addition, administration of FC to Col4a3KO mice corrected the increase in BP observed in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice (Fig7G–H). Overall, Col4a3KO-FC mice exhibited attenuated activation of MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways, two major signaling pathways for FGF23 (Fig7J). To test the immediate effects of FGF23 on the activation of these pathways, 10 week old WT mice received a single bolus of 100 μL of either 0.9% sodium chloride (Ctr), 25 μg/g ferric citrate (FC), 50 μg/g of sodium monobasic phosphate (Pi; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) or 50 ng/g of FGF23 (R&D Systems, MN, USA). Both phosphate and FGF23 induced MEK/ERK phosphorylation, while only FGF23 induced activation of PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT, suggesting that a reduction of MEK/ERK in CKD is likely due to a reduction of both phosphate and FGF23 burden, while decreased FGF23 explains the reduction in PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT activity (Fig7K). Further analysis showed that FGF23, and to a much lower extent iron, increases Egr1 expression and Nfat4 expression (Fig7L–P). Finally, phosphate but not FGF23 or iron appears to induce collagen expression (Fig7Q–S), while only FGF23 reduces Cyp27b1 and increases Cyp24a1 expression (Fig7T&U).

Figure 7: Ferric citrate administration in mice with early CKD slows CKD progression.

Levels of serum BUN (A), urine albumin (B) in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. Representative sections of kidney stained with hematoxylin & eosin or picro-sirius red staining (C, bar=50 μm) and renal mRNA expression of markers of fibrosis, Col1a1 (D), Col3a1 (E) and Col6a1 (F). Measurements performed in 10 week old WT and Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥5 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. Non-invasive systolic (G), diastolic (H) and mean blood pressure (I). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥11 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. (J) Representative immunoblots of kidney protein extracts stained for MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways activity. (K) Representative immunoblots of kidney protein extracts for MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways from 10 week old WT mice collected two hours post-injection of either 0.9% sodium chloride (Ctr), 25 μg/g ferric citrate (FC), 50 μg/g of sodium monobasic phosphate (Pi) or 50 ng/g of FGF23. Renal mRNA expression of FGF23 potential targets, Egr1 (L), Nfat1 (M), Nfat2 (N), Nfat3 (O), Nfat4 (P), markers of fibrosis, Col1a1 (Q), Col3a1 (R) and Col6a1 (S) and vitamin D enzymes Cyp27b1 (T), Cyp24a1 (T). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥3 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & WT-Pi mice.

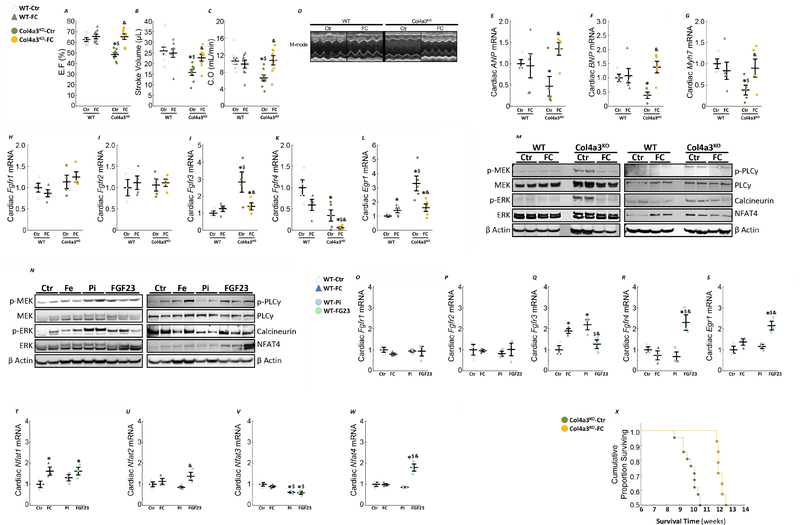

Ferric citrate supplementation in early CKD rescues systolic dysfunction

Compared to WT-Ctr mice, EF, stroke volume and CO were significantly lower in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice consistent with the development of systolic dysfunction (Fig8A–D). These alterations in cardiac function were significantly attenuated by FC in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig8A–D). In line with previous findings13, 33, expression of markers of hypertrophy were reduced (B-type natriuretic peptide -Bnp, Atrial natriuretic peptide-Anp, β-Myosin Heavy Chain- Myh7) in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice (Fig8E–G). Expression of Fgfr4, which mediates the hypertrophic effects of FGF23 on cardiac myocytes 12, was significantly reduced compared to WT-Ctr mice, whereas expression of Fgfr3 was significantly increased and paralleled increased Egr1 expression (Fig8H–L). FC further reduced Fgfr4 expression in Col4a3KO-FC mice but attenuated the increase of Fgfr3 and Egr1. Further analysis of MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways in the heart showed increased activity in Col4a3KO-Ctr mice compared to WT-Ctr mice, and a reduction in Col4a3KO-FC mice (Fig8M), perhaps due to reduced FGF23 signaling. Acute administration of phosphate and FGF23 to WT mice inducde MEK/ERK phosphorylation, while only FGF23 activates PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT. Thus, reduced MEK/ERK signaling in Col4a3KO-FC mice is mainly due to reduced phosphate and FGF23, while reduced PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT signaling might be attributed to decreased circulating FGF23 (Fig8N). Of note, phosphate administration reduces phosphorylation of PLC gamma. Iron and phosphate both increase the expression of Fgfr3, suggesting that higher levels of phosphate in CKD might increase FGF23 signaling through FGFR3. Acute administration of FGF23 paradoxically raises the expression of Fgfr4 and Egr1 expression in the heart (Fig8O–S). In line with our previous results FGF23, but not phosphate increases the expression of Nfat4 (Fig8T–W). Finally, as a likely consequence of the improvements in the renal and cardiac phenotypes following FC administration, Col4a3KO-FC mice lived an average of 2 weeks longer than Col4a3KO-Ctr mice, corresponding to a significant 20% extension of lifespan (Fig 8M).

Figure 8: Ferric citrate administration in mice with early CKD improves cardiac outcomes and survival.

Echocardiography analysis of left ventricular ejection fraction (A), stroke volume (B) and cardiac output (C) and M-mode echocardiography (D). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥8 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. mRNA expression of cardiac markers of hypertrophy ANP (E), BNP (F) and Myh7 (G)and FGF23 signaling Fgfr1 (H), Fgfr2 (I), Fgfr3 (J), Fgfr4 (K), Egr1 (L). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥3 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & Col4a3KO-Ctr mice. (M) Representative immunoblots of heart protein extracts stained for MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways activity. Measurements performed in 10 week old mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) during 6 weeks. (N) Representative immunoblots of heart protein extracts for MEK/ERK and PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT pathways from 10 week old WT mice collected two hours post-injection of either 0.9% sodium chloride (Ctr), 25 μg/g ferric citrate (FC), 50 μg/g of sodium monobasic phosphate (Pi) or 50 ng/g of FGF23. mRNA expression of cardiac markers FGF23 signaling Fgfr1 (O), Fgfr2 (P), Fgfr3 (Q), Fgfr4 (R), Egr1 (S), Nfat1 (T), Nfat2 (U), Nfat3 (V), Nfat4 (W). Data are presented as mean ± SE, n≥3 per group, p<0.05 vs.* WT-Ctr, $ WT-FC, & WT-Pi mice. (X) Cumulative proportion surviving of Col4a3KO mice fed a mineral sufficient diet (Ctr) supplemented or not with 5% ferric citrate (FC) starting at 4 weeks of age.

Discussion

Hyperphosphatemia, anemia and excess FGF23 are associated with adverse outcomes in patients with CKD 34–36. Ferric citrate, an iron-based phosphate binder, has shown promise in clinical studies to reduce phosphate absorption and FGF23 levels, and to replete iron stores and ameliorate anemia in CKD 28, 37–40. In two separate experiments using the Col4a3KO mouse model of progressive CKD, we show that administration of ferric citrate to animals with early or more advanced CKD decreases intestinal phosphate absorption, increases iron stores, corrects anemia and reduces FGF23 levels. Surprisingly, FC intervention beginning in animals with early CKD preserved renal function and mitigated the development of albuminuria and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. In addition, FC improved cardiac function of CKD mice in both experiments independently of its effects on CKD progression. Finally, improvement in mineral homeostasis and heart and kidney dysfunction significantly extended the lifespan of Col4a3KO mice.

Animals tolerated the relatively high dose of iron and showed no overt symptoms of iron overload in terms of activity or behavior, consistent with a low potential for iron overload by oral absorption 41 and even lower in patients with CKD who have high levels of hepcidin that downregulates intestinal iron absorption 42. Ferric citrate repleted iron stores and rescued anemia in CKD animals, as in prior human studies 43, independently of treatment duration despite a significant increase in hepatic hepcidin expression. It is unlikely that the increases in serum ferritin were related to increased inflammatory burden, because hepatic expression of Saa1, an inflammatory marker, was reduced, while TSAT and hepatic iron increased.

Our findings also show that oral ferric citrate performed as expected by reducing enteric phosphate absorption independently of treatment duration. In contrast to the 4-week FC diet, reduction of enteric phosphate reabsorption in early CKD animals supplemented with FC for 6 weeks led to a significant decrease in circulating phosphate levels. Overall, these findings suggest potential benefits of earlier intervention to reduce phosphate levels in CKD, even in the absence of overt hyperphosphatemia. Hyperphosphatemic Col4a3KO-Ctr also showed high duodenal expression of the sodium phosphate co-transporter Npt2b which mediates the active transport component of intestinal phosphate absorption. This suggests that the duodenal phosphate transport may be pathologically altered in the setting of CKD, but further studies are required.

As a likely consequence of increased iron and decreased phosphate absorption, FGF23 levels were significantly decreased following FC administration, similar to previous findings 30, 38, 39. Although FC treatment had different effects on serum phosphate and anemia depending on its timing of initiation and duration, FC reduced osseous Fgf23 transcription in Col4a3KO animals by ~3 fold, regardless of diet duration. Both the 4-week and 6-week administrations were successful in reducing circulating cFGF23 and iFGF23, with a more pronounced effect in the 6-week administration. Importantly, FC administration decreases FGF23 production in the 4-week study without reducing circulating phosphate levels in Col4a3KO-FC mice. This suggests that phosphate absorption rather than circulating phosphate controls FGF23 production, similar to prior findings 44.

Decreased phosphate absorption and reductions in iFGF23 resulted in a dramatic decrease in urine phosphate excretion in Col4a3KO-FC animals, which was reduced to the level of WT-Ctr despite ~3000pg/ml serum iFGF23, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism. A differential response in PTH to ferric citrate administration was also noted in clinical studies, in which reductions of FGF23 resulted in elevation of intact PTH levels in hemodialysis patients receiving ferric citrate 30, while PTH levels significantly decreased compared with baseline following ferric citrate treatment in CKD patients whereas FGF23 levels remained unchanged 38. Our findings are also consistent with previous studies describing lack of changes of PTH, and persistent downregulation of intact FGF23 upon inducible and global removal of Slc34a2, resulting in decreased intestinal phosphate absorption 45. This remarkable persistence of hyperparathyroidism in Col4a3KO-FC animals is even more intriguing given the modest but significant rescue of 1,25(OH)2D levels, likely due to iFGF23 reductions. This suggests that in addition to FGF23 and 1,25(OH)2D other mechanisms control PTH secretion in CKD.

Our results indicate that administration of ferric citrate has benefits extending beyond its effects on mineral metabolism. FC administration to animals with early CKD considerably improved kidney morphology and function. Although the pathogenesis of kidney injury is likely multifactorial, the duration of exposure to phosphate and FGF23 might affect the rate of the decline in renal function. Under physiological conditions, the intestinal absorption of phosphate is matched by an equivalent urinary excretion; a recent report showed that phosphaturia in patients with normal serum phosphate predicts renal disease progression 46. Col4a3KO mice show increased phosphate absorption, likely due to increased duodenal Slc34a2 mRNA, overt hyperphosphatemia and hyperphosphaturia, due to increased phosphaturic hormones FGF23 and PTH. Our data suggests that by directly reducing phosphate absorption and decreasing FGF23, leading to reduced phosphaturia, FC could attenuate kidney disease progression. Consistent with a potential pro-fibrotic effect of phosphate and FGF23 47, Col4a3KO-Ctr mice showed increased renal fibrosis that was reduced by FC along with parallel decreases in Col1a1, Col3a1, and Col6a1 mRNA expression. In addition, we further showed that acute administration of phosphate alone induces the expression of Col1a1 and Col6a1 in WT mice.

Administration of FC improved the cardiac phenotype of CKD mice independently of kidney function, since an improvement in cardiac function was observed in both studies, even in mice treated with FC from 6 to 10 weeks, in absence of measurable improvement in kidney function in Col4a3KO-FC mice. Col4a3KO-Ctr mice showed hypertension, reduced EF and stroke volume indicative of systolic dysfunction, but they did not develop LVH 33, which is the major cardiovascular phenotype associated with FGF23 excess in clinical and animal studies 5, 11, 12. Col4a3KO mice also show reduced markers of cardiac hypertrophy and decreased FGFR4. Thus, improvement in cardiac function following FC administration is unlikely due to reductions in FGF23-FGFR4 signaling. Although it is extremely challenging to dissociate the effects of phosphate, iron and FGF23 corrections on the heart, this suggests that reduction in FGF23, independently of kidney disease progression and circulating phosphate levels, might be associated with improvement of cardiac function. In this case, FGF23 could signal through other FGFR isoforms 48, including FGFR3 which is elevated in Col4a3KO mice 49, perhaps due to hyperphosphatemia. FGF23 activation of Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and/or Egr1 expression 49, 50 might induce systolic dysfunction, which is another clinical complication of CKD 51. Indeed, selective inhibition of Egr1 prevents the onset of systolic dysfunction 52. Consistent with this hypothesis, Col4a3KO-FC mice show decreased Egr1 compared to Col4a3KO-Ctr mice and MEK/ERK activation. Thus, this might represent another mechanism of FGF23-induced cardiac injury in CKD. Nonetheless, despite the reduction of Fgfr4 expression, PLCγ/calcineurin/NFAT activity is increased in CKD mice and attenuated by FC treatment suggesting that FGF23 may also signal through this pathway 11, 12.

Alternatively, the rescue of the cardiac phenotype in Col4a3KO-FC animals might be directly related to increased circulating iron and rescue of anemia, consistent with prior reports showing increased ejection fraction following iv iron administration 53, 54. Indeed, the heart is particularly susceptible to iron deficiency and anemia. The myocardium has a high demand in oxygen 55, thus reduced hemoglobin adversely impacts cardiac function. The heart also relies on free fatty acids as a primary energy source and restricted iron limits the synthesis of iron-sulfur proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation.

Although further studies testing the effects of FC in other models of CKD are needed to fully establish the beneficial effects of ferric citrate on kidney and cardiac functions, exploratory path analysis (SFig3) of changes in BUN partially mediated by changes in TSAT, and indirect additional significant effects of ferric citrate treatment. In addition, path analyses of changes of cardiac output, highlighted significant partial mediation of improvement in cardiac function by changes in iFGF23, TSAT and serum phosphate and additional indirect effects of ferric citrate treatment.

In aggregate, our results suggest that the combined corrections of FGF23 and phosphate excess and increases in iron stores following FC administration might improve the kidney and cardiovascular diseases in patients with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Heterozygous 129X1/SvJ-Col4a3tm1Dec mice were crossed to generate 129X1/SvJ-Col4a3+/+ (WT) and 129X1/SvJ-Col4a3−/− (Col4a3KO). Mice were maintained on a standard diet (Teklad 7012, Harlan Teklad, USA) containing 240 ppm iron, except when otherwise specified. To assess the effects of ferric citrate (FC), 4 week-old mice or 6 week-old mice were fed a mineral adequate control diet that contained 48 ppm of iron, enriched or not with 5% ferric citrate. In a separate set of animals, we recorded the age of death on ten Col4a3KO male littermates per group to assess effects on lifespan. Finally, 10 week-old WT mice received a single bolus of 100 μL of either 0.9% sodium chloride (Ctr), 25 μg/g ferric citrate (FC), 50 μg/g of sodium monobasic phosphate (Pi; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) or 50 ng/g of FGF23 (R&D Systems, MN, USA). Animals were collected two hours post-injection. All experiments were performed in male mice. All studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Northwestern University.

Biochemistry

We collected overnight urine samples from fasted animals housed overnight in metabolic cages and serum samples by intracardiac exsanguination. We used a murine intact FGF23 ELISA assay to measure the iFGF23 and a cFGF23 ELISA to measure total FGF23 (Quidel, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We measured parathyroid hormone (PTH) using a mouse intact ELISA (Quidel), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2 D] by immunoassay (Immundiagnostik Inc., Manchester, NH, USA) and calcium, phosphate, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), albumin, creatinine, iron and transferrin saturation (TSAT) using colorimetric assays (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI, USA). Serum ferritin and transferrin levels were measure using mouse ELISA assays (Alpco, Salem, NH, USA).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRI-reagent, and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from different organs 56. The iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system and iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) were used for real-time quantitative PCR analysis. The expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the same sample and expressed as fold-change versus wild-type.

Blood pressure

We measured blood pressure (BP) in sentient mice as previously described13, 33.

Echocardiography

We performed echocardiography under isoflurane anesthesia 1 week prior to sacrifice (at 9 weeks of age) as previously described 13, 33.

Hematologic analysis

Hematologic parameters were acquired in whole blood using the HEMAVET 950 hematology system (Drew Scientific Inc., Oxford, CT, USA) and analyzed with multispecies software using mouse settings.

Histology

Duodena, kidneys and livers were collected at sacrifice, fixed in 100% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. We collected 5-μm-thick sections using a rotary microtome. We stained the sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to determine duodenal, renal and hepatic morphology, picrosirius red (PSR) to determine renal fibrosis, and Perls’ prussian blue for iron content. Images were acquired using bright field microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA.

SDS-Page

Tissue lysates were prepared in using T-Per lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) containing protease inhibitors cocktail and immunoblots performed as previously described 24 using rabbit antibodies against phosphorylated Erk1/2 (p44/42 MAPK) (1:1000; 4370S; Cell Signaling), Erk1/2 (p44/42 MAPK) (1:1000; 4659S), phosphorylated MEK1/2 (1:1000; 9154S), MEK1/2 (1:1000; 9122L), phosphorylated phospholipase C gamma 1 (1:1000; 8713S), pan calcineurin (1:1000, 2614S), NFAT4 (1:1000, 4998S) from Cell Signaling (MA, USA) and rabbit anti-phospholipase C gamma 1 (1:1000; 76155) and goat anti-β Actin (1:1000, 8229) from abcam (MA, USA).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SE. ANOVA followed by Fisher and t tests were used for statistical difference using Statistica software (Statsoft, OK, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To test the major effects of ferric citrate treatment we used structural equation modeling (path analysis) using SEPATH module (SFig3). Generalized least square followed by maximum likelihood was used as discrepancy function to validate our model.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Ferric citrate administration to 9-week-old Col4a3KO mice decreases FGF23 production.

Supplementary Figure 2: Serum Calcium levels in WT and Col4a3KO mice.

Supplementary Figure 3: Path analysis of the major effects of Ferric Citrate treatment in Col4a3KO mice.

Supplementary Table 1: Iron and hematologic parameters in 6-week-old WT and Col4a3KO mice with moderate CKD.

Translational Statement.

Our study performed in an animal model of progressive CKD suggests that patients with CKD may benefit from a combined reduction of dietary phosphate intake and increased serum iron. In mice with CKD, early treatment with the iron based phosphate binder, ferric citrate, reduced the magnitude of FGF23 elevation, attenuated associated cardiovascular disease, slowed kidney disease progression, and prolonged survival. This suggests that ferric citrate might mitigate cardiac and renal injury and possibly improve survival in patients with CKD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Keryx pharmaceuticals to VD and by grants from National Institute of Health to VD (R01DK102815, R01DK114158), MW (R01DK076116) and AM (R01DK101730).

TI has received research support from Shire from Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and Regeneron and consulting honoraria from Bayer and Eli Lilly.

Disclosure

VD receives research funding from Keryx Biopharmaceuticals and has received research funding from Vifor Pharma and consulting honoraria from Keryx Biopharmaceuticals, Vifor Pharma, Luitpold and Amgen.

MW has received consulting fees from Keryx, Akebia, Amgen, Diasorin, Ardelyx, and Pharmacosmos.

Footnotes

All other authors have nothing to disclose

Supplementary information is available at Kidney International’s website.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shimada T, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, et al. FGF-23 transgenic mice demonstrate hypophosphatemic rickets with reduced expression of sodium phosphate cotransporter type IIa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004; 314: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pool LR, Wolf M. FGF23 and Nutritional Metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 2017; 37: 247–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. The New England journal of medicine 2008; 359: 584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2009; 119: 2545–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiler S, Reichart B, Roth D, et al. FGF-23 and future cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease before initiation of dialysis treatment. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2010; 25: 3983–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf M, Molnar MZ, Amaral AP, et al. Elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 is a risk factor for kidney transplant loss and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 956–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnlov J, Carlsson AC, Sundstrom J, et al. Higher fibroblast growth factor-23 increases the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the community. Kidney international 2013; 83: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baia LC, Humalda JK, Vervloet MG, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and cardiovascular mortality after kidney transplantation. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2013; 8: 1968–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacchetta J, Salusky IB, Hewison M. Beyond mineral metabolism, is there an interplay between FGF23 and vitamin D in innate immunity? Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2013; 28: 577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. The Journal of clinical investigation 2011; 121: 4393–4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabner A, Amaral AP, Schramm K, et al. Activation of Cardiac Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 Causes Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Cell metabolism 2015; 22: 1020–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dussold C, Gerber C, White S, et al. DMP1 prevents osteocyte alterations, FGF23 elevation and left ventricular hypertrophy in mice with chronic kidney disease. Bone research 2019; 7: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossaint J, Oehmichen J, Van Aken H, et al. FGF23 signaling impairs neutrophil recruitment and host defense during CKD. The Journal of clinical investigation 2016; 126: 962–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S, Grabner A, Yanucil C, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 directly targets hepatocytes to promote inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Kidney international 2016; 90: 985–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalhoub V, Shatzen EM, Ward SC, et al. FGF23 neutralization improves chronic kidney disease-associated hyperparathyroidism yet increases mortality. The Journal of clinical investigation 2012; 122: 2543–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isakova T, Ix JH, Sprague SM, et al. Rationale and Approaches to Phosphate and Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Reduction in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 2328–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ix JH, Isakova T, Larive B, et al. Effects of Nicotinamide and Lanthanum Carbonate on Serum Phosphate and Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 in CKD: The COMBINE Trial. 2019; 30: 1096–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foundation NK. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2006; 47: S11–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imel EA, Peacock M, Gray AK, et al. Iron modifies plasma FGF23 differently in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets and healthy humans. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2011; 96: 3541–3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrow EG, Yu X, Summers LJ, et al. Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011; 108: E1146–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinkenbeard EL, Farrow EG, Summers LJ, et al. Neonatal iron deficiency causes abnormal phosphate metabolism by elevating FGF23 in normal and ADHR mice. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2014; 29: 361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith ER, Cai MM, McMahon LP, et al. Biological variability of plasma intact and Cterminal FGF23 measurements. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2012; 97: 3357–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David V, Martin A, Isakova T, et al. Inflammation and functional iron deficiency regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Kidney international 2016; 89: 135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanudel MR, Chua K, Rappaport M, et al. Effects of dietary iron intake and chronic kidney disease on fibroblast growth factor 23 metabolism in wild-type and hepcidin knockout mice. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2016; 311: F1369–f1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinkenbeard EL, Hanudel MR, Stayrook KR, et al. Erythropoietin stimulates murine and human fibroblast growth factor-23, revealing novel roles for bone and bone marrow. Haematologica 2017; 102: e427–e430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabadi S, Udo I, Leaf DE, et al. Acute blood loss stimulates fibroblast growth factor 23 production. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2018; 314: F132–F139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokoyama K, Hirakata H, Akiba T, et al. Ferric citrate hydrate for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in nondialysis-dependent CKD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2014; 9: 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Block GA, Fishbane S, Rodriguez M, et al. A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ferric citrate for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia and reduction of serum phosphate in patients with CKD Stages 3–5. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2015; 65: 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iguchi A, Kazama JJ, Yamamoto S, et al. Administration of Ferric Citrate Hydrate Decreases Circulating FGF23 Levels Independently of Serum Phosphate Levels in Hemodialysis Patients with Iron Deficiency. Nephron 2015; 131: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stubbs JR, He N, Idiculla A, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2012; 27: 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai B, David V, Alshayeb HM, et al. Assessment of 24,25(OH)2D levels does not support FGF23-mediated catabolism of vitamin D metabolites. Kidney international 2012; 82: 1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuburg S, Dussold C, Gerber C, et al. Genetic background influences cardiac phenotype in murine chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2018; 33: 1129–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin A, Thompson CR, Ethier J, et al. Left ventricular mass index increase in early renal disease: impact of decline in hemoglobin. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 1999; 34: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Jama 2011; 305: 2432–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hara M, Nakamura Y, Suzuki H, et al. The hepcidin-25/erythroferrone ratio predicts improvement of anemia in hemodialysis patients treated with ferric citrate hydrate. Nephrology (Carlton, Vic) 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iguchi A, Yamamoto S, Yamazaki M, et al. Effect of ferric citrate hydrate on FGF23 and PTH levels in patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease with normophosphatemia and iron deficiency. Clinical and experimental nephrology 2018; 22: 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maruyama N, Otsuki T, Yoshida Y, et al. Ferric Citrate Decreases Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Improves Erythropoietin Responsiveness in Hemodialysis Patients. American journal of nephrology 2018; 47: 406–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCullough PA, Uhlig K, Neylan JF, et al. Usefulness of Oral Ferric Citrate in Patients With Iron-Deficiency Anemia and Chronic Kidney Disease With or Without Heart Failure. The American journal of cardiology 2018; 122: 683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleming RE, Ponka P. Iron overload in human disease. The New England journal of medicine 2012; 366: 348–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min HK, Sung SA, Oh YK, et al. Hepcidin, iron indices and bone mineral metabolism in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umanath K, Jalal DI, Greco BA, et al. Ferric Citrate Reduces Intravenous Iron and Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Use in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 2578–2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burnett SM, Gunawardene SC, Bringhurst FR, et al. Regulation of C-terminal and intact FGF-23 by dietary phosphate in men and women. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2006; 21: 1187–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabbagh Y, O’Brien SP, Song W, et al. Intestinal npt2b plays a major role in phosphate absorption and homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 2348–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santamaria R, Diaz-Tocados JM, Pendon-Ruiz de Mier MV, et al. Increased Phosphaturia Accelerates The Decline in Renal Function: A Search for Mechanisms. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith ER, Tan SJ, Holt SG, et al. FGF23 is synthesised locally by renal tubules and activates injury-primed fibroblasts. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu X, Ibrahimi OA, Goetz R, et al. Analysis of the biochemical mechanisms for the endocrine actions of fibroblast growth factor-23. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 4647–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Touchberry CD, Green TM, Tchikrizov V, et al. FGF23 is a novel regulator of intracellular calcium and cardiac contractility in addition to cardiac hypertrophy. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism 2013; 304: E863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamazaki M, Ozono K, Okada T, et al. Both FGF23 and extracellular phosphate activate Raf/MEK/ERK pathway via FGF receptors in HEK293 cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2010; 111: 1210–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dounaevskaia V, Yan AT, Charytan D, et al. The management of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Journal of nephrology 2011; 24: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rayner BS, Figtree GA, Sabaretnam T, et al. Selective inhibition of the master regulator transcription factor Egr-1 with catalytic oligonucleotides reduces myocardial injury and improves left ventricular systolic function in a preclinical model of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Heart Association 2013; 2: e000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Blum M, et al. The use of subcutaneous erythropoietin and intravenous iron for the treatment of the anemia of severe, resistant congestive heart failure improves cardiac and renal function and functional cardiac class, and markedly reduces hospitalizations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ponikowski P, Filippatos G, Colet JC, et al. The impact of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose on renal function: an analysis of the FAIR-HF study. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kodde IF, van der Stok J, Smolenski RT, et al. Metabolic and genetic regulation of cardiac energy substrate preference. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2007; 146: 26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.David V, Dai B, Martin A, et al. Calcium regulates FGF-23 expression in bone. Endocrinology 2013; 154: 4469–4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Ferric citrate administration to 9-week-old Col4a3KO mice decreases FGF23 production.

Supplementary Figure 2: Serum Calcium levels in WT and Col4a3KO mice.

Supplementary Figure 3: Path analysis of the major effects of Ferric Citrate treatment in Col4a3KO mice.

Supplementary Table 1: Iron and hematologic parameters in 6-week-old WT and Col4a3KO mice with moderate CKD.