Abstract

Objective:

Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT) is an aggressive tumor, with long term survival at ~30% in early stage disease. SCCOHT is caused by germline and somatic SMARCA4 mutations, but the effect of the mutation type on patients remains unknown. Furthermore, the rarity of SCCOHT has resulted in varied treatment, with no standardized protocols. We analyzed 293 cases to determine the effect of treatment modalities and SMARCA4 mutations on patient diagnosis and outcome.

Methods:

In 293 SCCOHT patients we collected information on age and stage at diagnosis, treatment modality (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue (HDC-aSCR)), SMARCA4 mutation origin (germline/somatic), and overall survival. Cox analysis and log-rank tests were performed on 257 cases with available survival data.

Results:

The strongest prognostic factors were stage at diagnosis (p = 2.72e-15) and treatment modality (p = 3.87e-13). For FIGO stages II-IV, 5-year survival was 71% for patients who received HDC-aSCR, compared to 25% in patients who received conventional chemotherapy alone following surgery (p = 0.002). Patients aged ≥40 had a worse outcome than younger patients (p = 0.04). Twenty-six of 60 tested patients carried a germline SMARCA4 mutation, including all patients diagnosed <15 years; carriers presented at a younger age than non-carriers (p = 0.02).

Conclusions:

Stage at diagnosis is the most significant prognostic factor in SCCOHT and consolidation with HDC-aSCR may provide the best opportunity for long-term survival. The large fraction of SMARCA4 germline mutations carriers warrants genetic counseling for all patients.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, chemotherapy, stem cell rescue, SCCOHT, SMARCA4, mutation

Introduction

Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT) is an uncommon but highly aggressive tumor diagnosed in young women at an average age of 24 years. The clinical and pathologic features of SCCOHT were initially outlined by Robert E Scully in 1979 [1]; small series have since been reported, with a clinical review presented in 2011 [2]. Outcome remains poor, with estimated long term survival at 33% in stage I disease, and 10–20% overall [2–4]. Due to its rarity, individual SCCOHT management has varied considerably, and no guidelines regarding optimal treatment currently exist.

In 2014 it was discovered that SCCOHT is characterized by both germline and somatic deleterious mutations in the gene SMARCA4 [5–8], which encodes the SMARCA4 protein (also called BRG1). It is one of two mutually exclusive enzymatic components of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, the other being SMARCA2. The most well-studied function of the SWI/SNF complex is in chromatin remodeling and the subsequent control of gene expression [9]. Since this finding, further studies have reported germline and somatic mutations in single cases or small series of affected women [10–14]. However, no studies have correlated the effects of mutation origin (germline or somatic) with clinical features and patient outcomes.

Aside from SCCOHT, germline mutations in SMARCA4 have been found to cause rhabdoid tumor predisposition syndrome type 2, a syndrome associated with the development of rhabdoid tumors, including atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRTs) that develop in the brain, and malignant rhabdoid tumors that develop most often in the kidney [15]. While >98% of these tumors are caused by inactivating mutations in SMARCB1, another SWI/SNF component, the remaining cases are associated with deleterious mutations in SMARCA4 [16]. SCCOHT closely resembles rhabdoid tumors on pathological, clinical, and molecular levels, and arguably represents malignant rhabdoid tumor of the ovary [17, 18].

Of the three studies with more than 50 SCCOHT cases [2, 4, 19], none have analyzed the frequency and influence of SMARCA4 mutations. To determine the most significant prognostic factors in SCCOHT, we have gathered 293 SCCOHT cases and analyzed the association of genetic, clinical, and therapeutic factors to patient outcome.

Methods

Cases

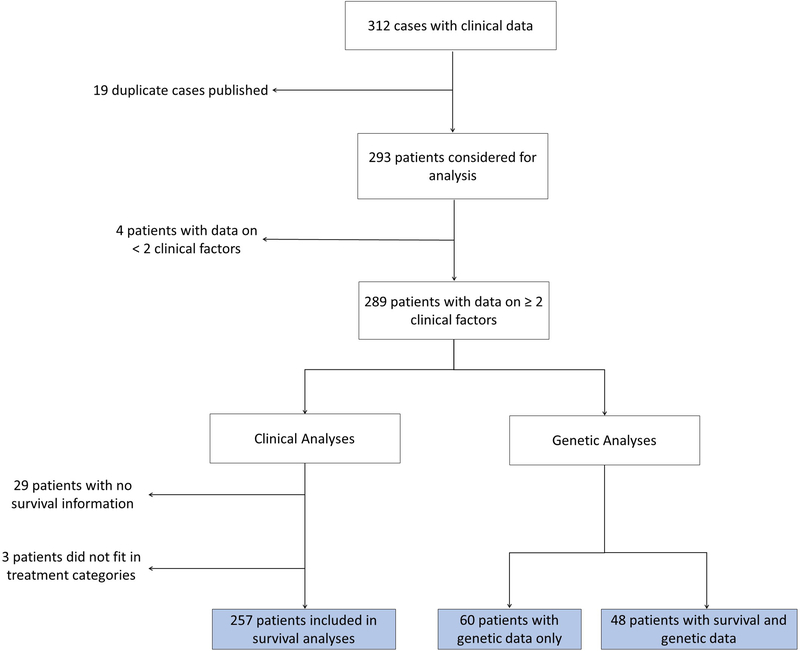

The study cohort comprised 267 previously published and 26 unpublished SCCOHT cases. All English language papers available on PubMed describing SCCOHT patients were compiled along with unpublished cases collected and analyzed in our laboratories (Supplementary Table S1). For each case we gathered available information on age and stage at diagnosis, treatment modalities used for primary disease, vital status, and overall survival (OS). For unpublished cases and those published after 2014, when the link between SMARCA4 and SCCOHT was established, immunohistochemical expression of SMARCA4 in the tumor, and the origin of SMARCA4 mutations (germline or somatic) was documented. In germline cases, inheritance patterns were recorded where available (Supplementary Table S2). Figure 1 summarizes the number of cases included in each analysis.

Figure 1.

Diagram of cases included in each analysis. Of 3 patients who did not fit treatment categories, 2 died before surgery, and one had chemotherapy with no surgery.

Statistical Analyses

We performed Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses on 257 SCCOHT cases with available OS information to determine which clinical factors had the greatest effect on patient outcome. We included a variable for missing information, which was applied to 59 cases with missing treatment or stage information; the results did not change significantly after removal of these cases.

Five treatment groups were assessed: surgery only, surgery with chemotherapy, surgery with radiotherapy, surgery with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and surgery with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue (HDC-aSCR) (Table 1). Three patients excluded from our analysis either died before surgery (n = 2), or received chemotherapy with no surgery (n = 1) [20–22].

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Vital Status (N) | Treatment Modality (N) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | N | Alive | Deceased | NA | Surg | Surg + Chemo |

Surg + RT |

Surg + Chemo + RT |

Surg + Chemo and/or RT + HDC |

NA |

| Age Group | ||||||||||

| 0–19 | 93 | 37 | 53 | 3 | 11 | 39 | 3 | 13 | 12 | 15 |

| 20–29 | 110 | 49 | 49 | 12 | 5* | 54† | 5 | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| 30–39 | 69 | 24 | 35 | 10 | 7 | 33 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 15 |

| 40+ | 21 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 1* | 7 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Total | 293 | 115 | 149 | 29 | 24 | 133 | 8 | 39 | 28 | 61 |

| FIGO Stage | ||||||||||

| I | 98 | 54 | 37 | 7 | 9 | 41 | 4 | 21 | 9 | 14 |

| II | 24 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| III | 108 | 34 | 67 | 7 | 5 | 55 | 3 | 9 | 13 | 23 |

| IV | 19 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 4** | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| NA | 44 | 16 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 19† | 0 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| Total | 293 | 115 | 149 | 29 | 24 | 133 | 8 | 39 | 28 | 61 |

Surg, Surgery; Chemo, Chemotherapy; RT, Radiation Therapy; HDC, High dose chemotherapy; NA, Not available

1 of these patients died before surgery

2 of these patients died before surgery

One of these patients had chemotherapy only

The origin of the SMARCA4 mutation (germline or somatic) was available in 60 of the 89 patients with mutation information available. Cox regression and log-rank tests were performed on 48 of these 60 patients in whom OS was known. All statistical analyses were performed using the ‘Survival’ and ‘car’ packages in R Bioconductor (https://www.bioconductor.org/).

Unpublished case details

For unpublished cases, germline DNA was available for 16 cases and was extracted as previously described [6, 7] from blood (n = 8), saliva (n = 5), or non-tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue (n = 3). Tumor DNA was extracted from FFPE (n = 19) or fresh frozen tumor (n = 2). Immunohistochemical staining for SMARCA4 and sequencing were performed as previously described [6, 7] or using a standard custom HaloPlex targeted capture (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

For 293 cases, details on age and stage at diagnosis, treatment modalities, vital status, and OS were recorded where available (Supplementary Table S1). Age was available for all patients (median = 25 years (1–71)); 270 patients (92%) were diagnosed between 10 and 40 years. Stage and treatment information were available for 249 and 232 patients, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the number of patients in each group.

One hundred fifteen patients (39%) were alive at last follow-up (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3, median follow-up of living patients = 33 months). Of 41 patients who were known to survive more than five years post-diagnosis, only three later died (at 63, 66, and 93 months), but those patients had relapsed at 26, 60, and 48 months respectively, suggesting that recurrence-free survival of longer than 60 months predicts long-term survival.

Multivariate comparison of clinical factors influencing outcome

Within the examined parameters, stage at diagnosis was the most significant determinant of survival (p = 2.72e-15, Table 2). Patients diagnosed at FIGO stage I had a 5-year survival rate of 55% (confidence interval (CI) = 44%−68%), whereas stage II and III patients had 5-year survival rates of 40% (CI = 23%−69%) and 29% (CI = 20%−41%), respectively. None of the stage IV patients survived past 13 months post-diagnosis (Figure 2A).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression

| Vital Status (N) |

Univariate (n=257) |

Multivariate (n=257) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Alive | Deceased | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Stage | 113 | 144 | 1.54E-10 | 2.72E-15 | ||

| 1* | 53 | 35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 11 | 12 | 1.79 (0.93–3.46) | 0.081 | 3.86 (1.91–7.84) | 1.79E-04 |

| 3 | 34 | 67 | 2.73 (1.81–4.11) | 1.77E-06 | 3.88 (2.45–6.14) | 6.93E-09 |

| 4 | 0 | 14 | 11.04 (5.76–21.15) | 5.54E-14 | 20.19 (9.84–41.45) | 2.22E-16 |

| Missing | 15 | 16 | 2.04 (1.13–3.69) | 0.019 | 1.60 (0.86–2.96) | 0.136 |

| Treatment | 113 | 144 | 1.47E-09 | 3.87E-13 | ||

| Surg* | 2 | 19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Surg+Chemo | 56 | 74 | 0.33 (0.20–0.55) | 1.94E-05 | 0.14 (0.08–0.26) | 9.46E-11 |

| Surg+RT | 3 | 5 | 0.28 (0.10–0.75) | 0.034 | 0.24 (0.08–0.68) | 7.54E-03 |

| Surg+Chemo+RT | 22 | 17 | 0.19 (0.10–0.37) | 4.65E-07 | 0.10 (0.05–0.21) | 1.66E-09 |

| Surg+Chemo/RT+HDC | 23 | 5 | 0.07 (0.03–0.20) | 2.19E-07 | 0.03 (0.01–0.09) | 1.20E-10 |

| Missing | 7 | 24 | 0.60 (0.33–1.10) | 0.099 | 0.36 (0.19–0.70) | 2.34E-03 |

| Age group | 113 | 144 | 0.18 | 0.02 | ||

| 0–19* | 36 | 52 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 20–29 | 49 | 47 | 0.85 (0.57–1.26) | 0.42 | 0.84 (0.55–1.28) | 0.42 |

| 30–39 | 23 | 34 | 1.21 (0.78–1.86) | 0.40 | 1.43 (0.90–2.25) | 0.13 |

| 40+ | 5 | 11 | 1.66 (0.87–3.19) | 0.13 | 2.11 (1.05–4.23) | 0.04 |

| Mutation Status | 113 | 144 | 0.13 | 0.45 | ||

| Somatic* | 14 | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Germline | 11 | 13 | 1.33 (0.58–3.04) | 0.50 | 0.63 (0.26–1.52) | 0.30 |

| Unknown | 88 | 121 | 1.76 (0.92–3.35) | 0.09 | 0.92 (0.46–1.86) | 0.82 |

Reference used for Hazard Ratio calculation. Overall p-values were taken from an ANOVA test and were used to determine signifcance of each category. Surg, surgery only; Surg + Chemo, Surgery and chemotherapy; Surg+RT, Surgery and Radiotherapy; Surg+Chemo+RT, Surgery, Chemotherapy, and Radiotherapy; Surg+Chemo/Rad+HDC, Surgery with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and high dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue. Alive and deceased numbers represent only patients included in the Cox analysis (n=258).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the effect of clinical factors on patient outcome. P-values were determined by log-rank tests. (A) Survival of SCCOHT patients according to stage at diagnosis. (B-C) Survival of patients according to treatment received for primary tumor in stage I patients (B) and stage II-IV patients (C). (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of SCCOHT patients according to age at diagnosis in years. Patients over 40 have a significantly worse outcome than younger patients as found by multivariate Cox analysis (p = 0.04). Surg, surgery only; Surg + Chemo, Surgery and chemotherapy; Surg+RT, Surgery and Radiotherapy; Surg+Chemo+RT, Surgery, Chemotherapy, and Radiotherapy; Surg+Chemo/RT+HDC, Surgery with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue.

The next strongest determinant of survival was treatment modality (p = 3.87e-13, Table 2). Of 28 patients who received HDC-aSCR, 23 were alive at last follow-up (Supplementary Table S4). Due to the significantly better prognosis of stage I than stage II-IV patients [2], we separated these groups for treatment analyses. In all stages, log-rank and Cox regression analyses showed that addition of HDC-aSCR resulted in better OS than standard chemotherapy alone (Table 2, Figure 2B-C), with 100% of stage I patients and 71% of stage II-IV patients (CI = 52%−97%) alive after 5 years; however, this difference was only significant in stage II-IV patients (Figure 2B-C, p = 0.007 for stages II-IV); only 25% of stage II-IV patients who received chemotherapy alone lived longer than five years. The addition of radiotherapy did not improve outcome compared to chemotherapy alone in patients of all stages (p = 0.19 in stages II-IV). Patients treated with surgery alone had the poorest outcome, with a median OS of 5 months and only 2/22 patients were alive at last follow-up. Of 131 patients who received surgery with chemotherapy alone, the median OS was 14.5 months.

When comparing four age groups (0–19 years, 20–29 years, 30–39 years, and ≥40 years), we found that patients diagnosed at 40 years or older had a worse outcome than younger patients (Figure 2D, Table 2, hazard ratio = 2.11 (CI = 1.05–4.23, p = 0.04)).

SMARCA4 mutation spectrum in SCCOHT

Of 89 patients for whom SMARCA4 data was available, 26 had germline mutations, 34 had somatic mutations only, and in 29 cases the mutation origin was unknown (Supplementary Table S2). Of the 26 (43%) germline mutation carriers, 21 had no reported family history of SCCOHT. Inheritance patterns were available in 10 patients (from 8 families). One mutation arose de novo, while 8 mutations were inherited: 4 from unaffected fathers, 4 from affected mothers, and one case where the parents were not tested, but the siblings carried the mutation [23, 24]. (Supplementary Table S2).

Thus far, 96 unique SMARCA4 mutations have been described [5–8, 10–14, 25, 26]; the types of mutations have varied and include 21 splice mutations, 25 stop mutations, 41 frameshift mutations, 6 missense mutations, 2 in-frame deletions and 1 synonymous mutation (Supplementary Table S2). Regardless of the mutation type, however, almost all have led to loss of the SMARCA4 protein, with only 2 mutations leading to retained SMARCA4 protein: a missense mutation (p.Glu1080Asp) [7] and an in-frame deletion (Supplementary Table S2) [5].

Germline SMARCA4 mutations and Clinicopathological Factors

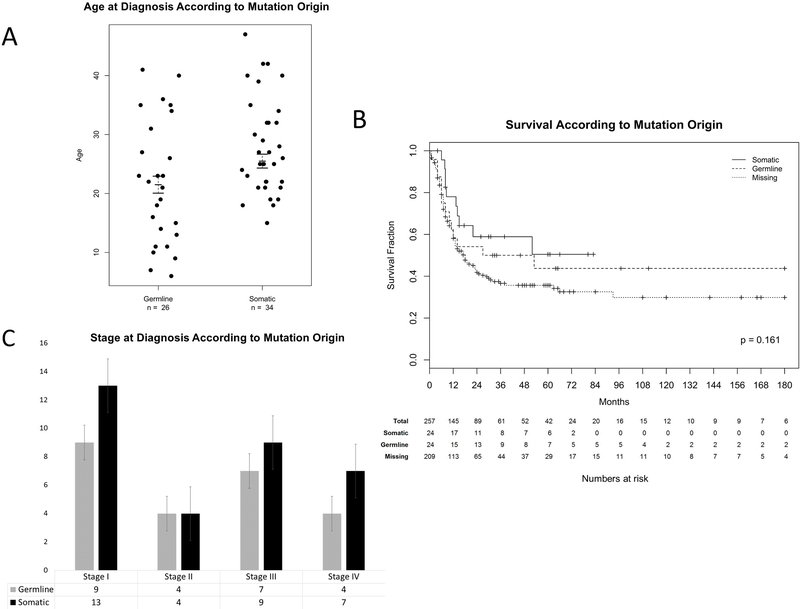

The 26 patients carrying germline mutations were diagnosed at a significantly younger median age (21.5 years) than the 34 non-carriers (25.5 years, p = 0.02, Mann-Whitney U test, Figure 3A). All eight tested patients diagnosed under 15 years carried a germline mutation. The odds ratio of carrying a germline mutation if diagnosed below 18 years was 20.63 (CI 2.4–175.4, p = 5.50e-04). A multivariate Cox regression analysis on 48 cases with available genetic and OS information showed no significant difference in OS or in relative risk of death from disease between patients with (n = 24) or without (n = 24) germline SMARCA4 mutations (multivariate p = 0.30, Table 2, Figure 3B). A chi-squared test comparing patients with germline and somatic SMARCA4 mutations showed no significant difference in tumor stage (p = 0.53, Figure 3C), although the small sample size precludes a conclusive analysis.

Figure 3.

The effect of mutation origin on SCCOHT patients. (A) Stripchart showing difference in age at diagnosis between patients with germline mutations and those with somatic mutations only. Each dot represents one patient. Black bars are mean and standard error. Median age at diagnosis was 21.5 for patients with germline mutations and 26 for patients with somatic mutations only. P = 0.02 by Mann-Whitney U test. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of SCCOHT patients according to SMARCA4-carrier status. The difference between somatic and germline patients only was not significant by log-rank test (p = 0.09). We suspect that the slight difference in survival between tested and non-tested patients is due to ascertainment bias. (C) Distribution of stage at diagnosis of patients with germline mutations or somatic mutations only. No significant difference was seen between the two groups (p = 0.53, Chi-squared test).

Discussion

Here we compiled data on all published and a series of unpublished SCCOHT cases in an attempt to determine which factors may have a significant effect on patient diagnosis and outcome. Stage at diagnosis was the most significant prognostic factor, consistent with previous studies [2, 4, 19]. Once the patient has been staged, the best opportunity for long-term survival is multimodal therapy that includes HDC-aSCR. At least 20/28 patients who received HDC-aSCR showed a complete response to chemotherapy prior to receiving HDC-aSCR, and only 5/20 (25%) relapsed (Supplementary Table S4). This suggests that the most effective use for this modality is in preventing recurrence, as overall relapse rates were previously reported to be 65% [2]. Importantly, we found that patients who had not relapsed within five years of diagnosis are likely to be cured.

Genetically, 35% (21/60) of patients with no family history of SCCOHT carried a SMARCA4 germline mutation. Similar to other cancer predisposition syndromes, patients with germline mutations were diagnosed at a younger age (median = 21.5 vs 25.5 years for non-carriers, p = 0.02, Figure 3A) [27], and all patients under 15 years carried germline mutations (n = 8). Contrary to previous studies [19], our data showed that patients aged 40 years or older had a poorer outcome (Table 2, Figure 2D). While the previously recorded oldest age of onset of SCCOHT is 71 years, the oldest reported patient with SMARCA4 loss is 56 years; therefore, cases diagnosed older than 60 years may represent misdiagnoses. As SMARCA4 immunohistochemical staining can now be used as a diagnostic tool to correctly diagnose SCCOHT, the true age range of SCCOHT will be more apparent in the future.

It is clear that surgery alone is not adequate treatment for SCCOHT, even in early stages [28, 29]. Currently no standard therapy exists, and retrospective examination of chemotherapy regimens has reached varying conclusions [2, 20]. Combined surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy has been used in most SCCOHT cases based on recommendations in other ovarian tumors and small cell lung carcinoma. However, despite similar nomenclature, SCCOHT is genetically distinct from small cell carcinoma of neuroendocrine type and ovarian epithelial and non-epithelial cancers, but rather resembles a rhabdoid tumor [17].

Although randomized clinical trials are challenging in this rare disease, our review suggests that HDC-aSCR represents the best opportunity for long-term survival. In the two largest studies describing patients who received HDC-aSCR, 28/38 patients had a complete response to standard chemotherapy, half of whom subsequently received HDC-aSCR. Of these 14 patients, only 3 relapsed and one died, whereas of the 14 who did not receive HDC-aSCR, 11 relapsed and 7 died [28, 30]. While patients ideally have a complete chemotherapy response prior to receiving HDC-aSCR, one patient has been reported to receive HDC-aSCR following a partial response and ultimately survived long term [31]. Several other reports support the superiority of HDC-aSCR and its curative potential for patients with SCCOHT [10, 29, 31–36] (Supplementary Table S4).

Reports documenting radiotherapy use in SCCOHT provide conflicting results, making the role of this treatment modality unclear [3]. In our study, addition of radiotherapy did not significantly increase OS compared to chemotherapy alone (p = 0.19), although small patient numbers limited conclusive results.

An important consideration in the treatment of patients with SCCOHT is the similarity between SCCOHT and rhabdoid tumors. The morphological, genetic, and epigenetic overlap between SCCOHT and rhabdoid tumors is clear [17, 18], but differences in age of onset and tumor location has masked these similarities and has resulted in distinct tumor management. In ATRT, multimodal therapy and HDC-aSCR have been incorporated into the treatment guidelines [37]. In ATRT, multimodal therapy and HDC-aSCR have proven beneficial and have been incorporated into the treatment guidelines of these tumors [15, 37–39]. In extra-cranial rhabdoid tumors, although not yet standard of care, HDC-aSCR has also shown to be beneficial [40]. Similarly, our data suggest that incorporating HDC-aSCR into the therapeutic regimen for SCCOHT gives the best opportunity for survival.

As 43% of tested patients carried a germline SMARCA4 mutation, all SCCOHT patients should be referred to a genetics service. Of 26 mutation carriers, familial genotypes were available in 8 families, three of which included an unaffected female carrier; however, all were still younger than 40 years [7, 12]. While the penetrance of these mutations remains unclear, only one female SMARCA4-mutation carrier has been reported healthy past her sixth decade [16].

Given these results, all at-risk relatives of a SMARCA4 germline mutation carrier should receive genetic counseling. The efficacy of ovarian surveillance for at-risk females is undetermined, but until data are available, ovarian imaging is a reasonable option for at-risk females. Bilateral oophorectomy would likely be an effective preventive measure for females with a germline mutation [23], but without penetrance data, determining the optimal age to consider this option is difficult.

We recognize that a major limitation of this study is that the analysis was based mainly on published data, potentially limiting available details in recruited cases. Furthermore, the small number of patients and disproportionate weights of different stage and treatment modality groups limits the statistical significance of our analyses. Thirdly, estimation of the effect of germline mutations on development and progression of SCCOHT was restricted, as germline DNA was available in only 20% of the cases.

Nevertheless, this is the largest study on SCCOHT to date and is the first to analyze the outcome of patients based on treatment modalities and SMARCA4 mutations. The data presented suggest that HDC-aSCR offers the best chance of cure, but international collaboration will be required to test this further. As targeted therapies have already proven effective in other cancers with specific driver mutations, there is hope that similar therapies could be developed for SMARCA4-deficient cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the families and patients for their important contributions to this study, as well as the clinical and sample acquisition support provided by many physicians: Drs. Stephen P. Anthony, Blaise A Clarke, Mrs. Ariane Dunant, Drs. John H. Farley, Sara Fernandez, Marc Gander, Martin Gore, Olivier Ingster, Conxi Lazaro, Patricia M. LoRusso, Bradley J. Monk, Joseph G. Pressey, Richard Roden, Marc Tischkowitz, Claire Senechal, Ms. Darcy Thull, Dr. Daniel D. Von Hoff, and Dr. James J. Vredenburgh. We thank John R Priest for his critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was supplied by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé and CCSRI Innovation Grant (WDF); National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA195670. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by grants from The Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research, The Anne Rita Monahan Foundation, The Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, The Small Cell Ovarian Cancer Foundation, and Foster and Lynn Friess (WH, PR, HC, JT).

Footnotes

Disclosure

Patricia Pautier is a consultant for Roche, PharmaMar, and GlaxoSmithKline. David G Huntsman is partial owner of Contextual Genomics. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Scully RE. Tumors of the ovary and maldeveloped gonads In: Hartmann WH, Cowan WR, editors. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. second series, fascicle 16 ed. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Estel R, Hackethal A, Kalder M, Münstedt K. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary of the hypercalcaemic type: an analysis of clinical and prognostic aspects of a rare disease on the basis of cases published in the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(5):1277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Callegaro-Filho D, Burke TW, Eifel PJ, Ramirez PT, Euscher EE, Schmeler KM. Radiotherapy for recurrent small cell carcinoma of the ovary: A case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2015;11:23–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jamy O, Yaghmour G, Hare F, Martin MG. Population-based Analysis of the Clinical Features of Primary Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(5):3091–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jelinic P, Mueller JJ, Olvera N, Dao F, Scott SN, Shah R, et al. Recurrent SMARCA4 mutations in small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):424–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ramos P, Karnezis AN, Craig DW, Sekulic A, Russell ML, Hendricks WP, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type, displays frequent inactivating germline and somatic mutations in SMARCA4. Nat genet. 2014;46(5):427–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Witkowski L, Carrot-Zhang J, Albrecht S, Fahiminiya S, Hamel N, Tomiak E, et al. Germline and somatic SMARCA4 mutations characterize small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):438–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kupryjańczyk J, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Moes-Sosnowska J, Plisiecka-Hałasa J, Szafron L, Podgórska A, et al. Ovarian small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type - evidence of germline origin and SMARCA4 gene inactivation. a pilot study. Pol J Pathol. 2013;64(4):238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Witkowski L, Foulkes WD. In Brief: Picturing the complex world of chromatin remodelling families. J Pathol. 2015;237(4):403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bailey S, Murray MJ, Witkowski L, Hook E, Hasselblatt M, Crawford R, et al. Biallelic somatic SMARCA4 mutations in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(4):728–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jelinic P, Schlappe BA, Conlon N, Tseng J, Olvera N, Dao F, et al. Concomitant loss of SMARCA2 and SMARCA4 expression in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(1):60–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moes-Sosnowska J, Szafron L, Nowakowska D, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Budzilowska A, Konopka B, et al. Germline SMARCA4 mutations in patients with ovarian small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rabinovich A, Witkowski L, Shaco-Levi R, Meirovitz M, Hasselblatt M, Foulkes WD. Primary rhabdoid tumor of the ovary: When large cells become small cells. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2015;12:64–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ramos P, Karnezis AN, Hendricks WPD, Wang Y, Tembe W, Zismann VL, et al. Loss of the tumor suppressor SMARCA4 in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT). Rare Dis. 2014;2(1):e967148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brennan B, Stiller C, Bourdeaut F. Extracranial rhabdoid tumours: what we have learned so far and future directions. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):e329–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hasselblatt M, Nagel I, Oyen F, Bartelheim K, Russell RB, Schuller U, et al. SMARCA4-mutated atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors are associated with inherited germline alterations and poor prognosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(3):453–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fahiminiya S, Witkowski L, Nadaf J, Carrot-Zhang J, Goudie C, Hasselblatt M, et al. Molecular analyses reveal close similarities between small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. Oncotarget. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Foulkes WD, Clarke BA, Hasselblatt M, Majewski J, Albrecht S, McCluggage WG. No small surprise - small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcaemic type, is a malignant rhabdoid tumour. J Pathol. 2014;233(3):209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Young RH, Oliva E, Scully RE. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. A clinicopathological analysis of 150 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(11):1102–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Harrison ML, Hoskins P, du Bois A, Quinn M, Rustin GJS, Ledermann JA, et al. Small cell of the ovary, hypercalcemic type—Analysis of combined experience and recommendation for management. A GCIG study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(2):233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Idei Y, Kitazawa S, Fujimori T, Ajiki T, Asaka K, Takeuchi S, et al. Ovarian small cell carcinoma with K-ras mutation: A case report with genetic analysis. Hum Pathol. 1996;27(1):77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Saikia UN, Malhotra P, Khandelwal N, Varma S, Joshi K. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary presenting as bone marrow metastasis: a rare presenting feature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2005;48(3):402–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Berchuck A, Witkowski L, Hasselblatt M, Foulkes WD. Prophylactic oophorectomy for hereditary small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2015;12(0):20–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Martinez-Borges AR, Petty JK, Hurt G, Stribling JT, Press JZ, Castellino SM. Familial small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Pediatr Blood Canc. 2009;53(7):1334–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Le Loarer F, Watson S, Pierron G, de Montpreville VT, Ballet S, Firmin N, et al. SMARCA4 inactivation defines a group of undifferentiated thoracic malignancies transcriptionally related to BAF-deficient sarcomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lavrut P-M, Le Loarer F, Normand C, Grosos C, Dubois R, Buenerd A, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type/ ovarian malignant rhabdoid tumor: report of a bilateral case in a teenager associated with SMARCA4 germline mutation. Pediatr Dev Path. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Stuckey AR, Onstad MA . Hereditary breast cancer: an update on risk assessment and genetic testing in 2015. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Distelmaier F, Calaminus G, Harms D, Sträter R, Kordes U, Fleischhack G, et al. Ovarian small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type in children and adolescents. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pressey JG, Kelly DR, Hawthorne HT. Successful treatment of preadolescents with small cell carcinoma of the ovary hypercalcemic type. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(7):566–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pautier P, Ribrag V, Duvillard P, Rey A, Elghissassi I, Sillet-Bach I, et al. Results of a prospective dose-intensive regimen in 27 patients with small cell carcinoma of the ovary of the hypercalcemic type. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(12):1985–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Christin AA. Successful treatment for advanced small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(6):1276–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kopp LM, Desoky S, Pugh J, Herzog CE. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary of the Hypercalcemic Type Presenting in a 5-Year-Old Girl. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(5):e217–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Origoni H. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary: Report of Three Cases of a Poor Prognosis Disease. J Med Cases. 2013;4(3):189. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schleef J, Wagner A, Kleta R, Schaarschmidt K, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Willital GH, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the ovary of the hypercalcemic type in an 8-year-old girl. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999;15(5–6):431–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schultz KAP, Sencer SF, Messinger Y, Neglia JP, Steiner ME. Pediatric ovarian tumors: A review of 67 cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(2):167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Woopen H, Sehouli J, Pietzner K, Darb-Esfahani S, Braicu EI, Fotopoulou C. Clinical experience of young patients with small cell ovarian carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type (OSCCHT). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(2):313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Benesch M, Bartelheim K, Fleischhack G, Gruhn B, Schlegel PG, Witt O, et al. High-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with auto-SCT in children with atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (AT/RT): a report from the European Rhabdoid Registry (EU-RHAB). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2014;49(3):370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lafay-Cousin L, Hawkins C, Carret AS, Johnston D, Zelcer S, Wilson B, et al. Central nervous system atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours: The Canadian Paediatric Brain Tumour Consortium experience. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(3):353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lau CSM, Mahendraraj K, Chamberlain RS. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors: a population-based clinical outcomes study involving 174 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1973–2010). Cancer Manag Res. 2015;7:301–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Venkatramani R, Shoureshi P, Malvar J, Zhou S, Mascarenhas L. High dose alkylator therapy for extracranial malignant rhabdoid tumors in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(8):1357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.