Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, head and neck, head and neck neoplasia, cytology diagnostic certainty, fine needle aspiration cytology, developmental neck masses

Primary Objective

Objective HN2.4: Developmental Neck Masses and Other Neck Tumors. Compare and contrast developmental lesions that present as masses in the neck (branchial cyst and thyroglossal duct cyst) from a paraganglioma including pathogenesis and morphologic features of each.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology; Topic HN: Head and Neck; Learning Goal 2: Head and Neck Neoplasias.

Secondary Objective

Objective CYP2.1: Screening. Describe the principles of an effective screening test and the uses and limitations of cytology.

Competency 3: Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology; Topic CYP: Cytopathology; Learning Goal 2: Advantages of Cytopathology.

Patient Presentation

A 31-year-old woman presented with painless swelling in the right side of the lateral neck region. She stated that the swelling was initially small and gradually increased in size for the past 3 years. No pain, numbness, tingling, or dysphagia were reported.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 1

On physical examination, a single, well-circumscribed oval swelling measuring 3.0 × 2.0 cm was observed in the right upper part of the neck. The swelling extended anteriorly from the angle of the mandible and posteriorly to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The overlying skin appeared unremarkable with no associated redness or discoloration. On palpation, the swelling was nontender, smooth, and rubbery in consistency. An ultrasound was performed and revealed a compressible, round-oval, homogenous, hypoechoic mass with well-defined margins and thin walls, consistent with a cyst. A superficial fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy was performed in the office under local anesthesia to assess the possible causes of this mass. The pathologist performed 3 FNA passes using 25-gauge needles without suction, and the initial smears show adequate cellularity.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 1

What Is the Differential Diagnosis of a Cystic Neck Mass in an Adult?

The differential diagnosis of cystic lesions in the neck is broad and includes various developmental neck cysts (see below), reactive lymph nodes, lymphoma, cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, and other metastatic carcinomas such as metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma and other malignancies.2

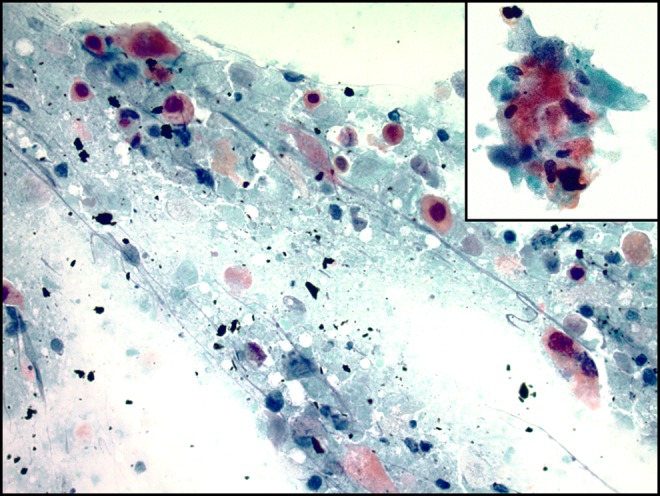

The most critical differential diagnosis of a cystic neck mass in an adult patient is to rule out metastatic carcinoma and lymphoma. Although squamous-lined non-neoplastic cysts can show mild reactive atypia, cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma will generally show more significant atypia. These atypical squamous cells are characterized by hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular nuclear contours, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, mitotic activity, and a background of necrosis (Figure 1). Therefore, FNA cytology is valuable as a presurgical screening tool to rule out a cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.3,4 Pure lymphoid lesions point to either a reactive lymphadenopathy or a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphoma. The latter would usually show a monomorphic and/or atypical population of lymphocytes.

Figure 1.

Papanicolaou stain at ×400 of a fine needle aspiration (FNA) smear of a cystic squamous cell carcinoma showing keratinized squamous cells with marked cytologic atypia, including irregular nuclear contours, nuclear hyperchromasia, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and a background of necrotic debris and cystic contents. The pink-orange color of the cytoplasm (orangeophilia) is consistent with squamous (keratinized) differentiation. Inset: close-up of atypical squamous cells (×400).

Accordingly, it is prudent to conduct a thorough screening before diagnosing a developmental cyst in an adult; many savvy clinicians suggest that there is “essentially no such thing as a branchial cleft cyst in a patient over 50” to emphasize this point. It is critical to undergo careful clinical correlation in older patients or those with major risk factors to exclude a more clinically significant lesion. Any persistent lesions should likely be excised to confirm the diagnosis.

After excluding malignancy, the next major consideration is developmental neck cysts. In this young patient with no history of malignancy, the most likely differential diagnosis would be a developmental abnormality. Specifically, based on location, that is, lateral neck, the top considerations would be branchial cleft cyst (more common) and lymphangioma (cystic hygroma), followed by rarer entities such as cervical thymic cysts. On the other hand, the differential diagnosis of developmental cysts in the midline neck includes thyroglossal duct cyst (most common), epidermoid inclusion cyst, and dermoid cyst.5,6

What Is the Value of Performing In-Office Fine Needle Aspiration in the Evaluation of Cystic Neck Lesions?

Although the aspirate findings of neck cysts are often nonspecific, cytologic examination is excellent at distinguishing benign lesions from malignancy, which allows for planning for the appropriate management.3 It is important to note that cytology cannot always distinguish the type of malignancy, as limited material may preclude ancillary testing. However, this will prompt further workup to obtain additional tissue, such as the use of radiologically guided core biopsies or surgical excisional biopsies. If the lesion is determined to be a metastatic carcinoma, this will prompt further workup to determine the primary site of the tumor. If the lesion is determined to be a lymphoproliferative disorder, this will prompt additional ancillary testing, such as flow cytometry and molecular testing, to provide a specific diagnosis, guide further radiological workup to determine the extent of systemic involvement, and consideration for the appropriate medical oncological management, such as systemic chemotherapy or radiation therapy. If the lesion is determined to be benign, a limited surgical excision may be considered for symptom control.

What Are the Fine Needle Aspiration Morphologic Features of the Most Common Cystic Neck Masses in Adults?

The cytologic findings of neck cysts are highly variable, and often may be nonspecific. Cytologic findings of branchial cleft cysts include mature squamous cells with centrally located, small round nuclei, anucleate squamous cells, and proteinaceous debris admixed with mature lymphocytes and histiocytes.7,8 On the other hand, in thyroglossal duct cysts, abundant cyst contents with ciliated columnar epithelium is most commonly seen (Figure 2).9,10 Nevertheless, admixed squamous cells are often present and could lead to confusion with squamous-lined cysts, such as brachial cleft cysts and epidermoid inclusion cysts. The cytologic findings of cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma include atypical squamous cells showing hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular nuclear contours, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, mitotic activity, and a background of necrosis (Figure 1).3

Figure 2.

Papanicolaou stain at ×400 of a fine needle aspiration smear of a thyroglossal duct cyst showing ciliated, columnar epithelial cells in clusters with basally aligned nuclei with smooth nuclear contours and no cytological atypia. Arrow: cilia. Inset: close-up of ciliated, columnar epithelial cells (×400).

Diagnostic Findings, Part 2

The cytology findings of the current case are shown in Figure 3. The aspirate shows clusters of mature, bland squamous cells and keratin debris admixed with lymphocytes, and histiocytes with proteinaceous debris. The squamous cells have a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, small round nuclei without hyperchromasia, and abundant keratinized cytoplasm. Occasional anucleate squamous cells are present. These findings are consistent with a benign cyst with squamous epithelial lining and would be compatible with a branchial cleft cyst.

Figure 3.

Papanicolaou stain at ×200 (A) and ×400 (B-D) of the initial fine needle aspiration (FNA) smear showing mature squamous cells with centrally located, small round nuclei, anucleate squamous cells, and proteinaceous debris (A, B), admixed with mature lymphocytes and histiocytes (C, D). Arrow: lymphocytes. Arrowhead: histiocytes.

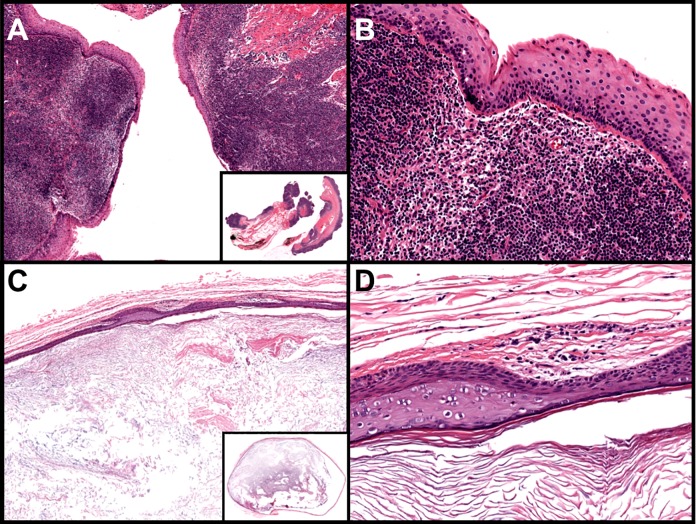

Given symptomatic persistent mass effect, the patient elected to undergo surgical excision of the cyst. Histologic sections from the resection specimen demonstrated a cystic structure lined by stratified squamous epithelium with underlying lymphoid aggregates in the cyst wall (Figure 4A and B). These findings, in conjunction with the location in the lateral neck, are diagnostic of a second branchial cleft cyst.

Figure 4.

A and B, Branchial cleft cyst: nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium-lined cysts with abundant lymphocytic aggregates within the cyst wall (A: ×40 [inset: whole slide], B: ×200). C and D, Epidermoid inclusion cyst: thin-walled cysts with a keratinized squamous epithelium lining containing a granular layer; the cyst contains abundant keratin debris or laminated keratin (C: ×40 [inset: whole slide], D: ×200; hematoxylin and eosin staining).

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 2

Describe the Histologic Appearance, Embryologic Origin, and Classification of Branchial Cleft Cysts

Branchial cleft cysts

Branchial cleft cysts are generally located in the lateral neck near the mandibular angle and make up to 20% of all congenital neck cysts. Although rare, branchial cleft cysts represent one of the most common congenital anomalies encountered in pediatric otolaryngologic practices. The most common epithelial lining is squamous, although occasionally, respiratory or transitional epithelium can be seen in the lining, especially in uninflamed cysts. The wall of the cyst nearly always contains lymphoid hyperplasia. Sometimes, reactive germinal centers are present and could resemble a reactive lymph node; however, true lymph node architecture, such as subcapsular sinuses or interfollicular zones, is absent. Acute and chronic inflammation are also frequently seen. In many cases, the lumen is filled with keratinaceous debris. Importantly, the squamous epithelium should not show dysplasia, pleomorphism, or increased mitoses (Figure 4A and B).11

Second branchial cleft cysts comprise approximately 80% to 90% of all branchial cleft anomalies. They arise from the second branchial cleft remnant, which itself arises from the branchial apparatus, the precursor of many head and neck structures (Figure 5A and B). The embryogenesis of the branchial apparatus is usually complete by 6 to 7 weeks of gestation. When the second branchial arch overgrows the second, third, and fourth branchial clefts, forming the developmental cervical sinus, the failure of its obliteration results in the second branchial cleft remnant. The native sinus is lined by respiratory epithelium, but as a result of immunologic stimulation during inflammation or infection, the respiratory epithelial lining often undergoes squamous metaplasia, resulting in the characteristic squamous epithelial lining most often seen in branchial cleft cysts. The cyst wall nearly always develops lymphoid hyperplasia, resulting in the classic pathologic features seen in Figure 4. In addition to cysts, second branchial cleft remnants can also give rise to fistulas, which extend from the anterior skin to the sternocleidomastoid muscle through the carotid artery bifurcation to terminate in the tonsillar fossa.

Figure 5.

A, The branchial apparatus at fifth week of gestation including the branchial arches, the external branchial clefts, and internal branchial pouches prior to obliteration. B, The anatomical locations of the first, second, and third branchial cleft remnants in the lateral neck, which could give rise to branchial cleft cysts, sinuses, or fistula tracts.

A minority (8%) of branchial cleft-derived cysts/sinuses arise from the first branchial arch and are known as first branchial cleft cysts. These cysts typically present as recurrent swelling or sinus drainage at the preauricular or postauricular region (type I first branchial cleft cyst/sinus) or the anterior neck, superior to the hyoid (type II first branchial cleft cyst/sinus; Figure 5A and B).

Finally, fewer than 5% of all branchial cleft cysts are third and fourth branchial cleft cysts (Figure 5A and B). These cysts are located above and below the superior laryngeal nerve, respectively. Most third branchial cleft cysts are located in the posterior cervical space, posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and can present as recurrent neck abscesses. The vast majority of fourth branchial cleft cysts are left sided and most often present as fistulae/sinus tracts coursing from the apex of the pyriform fossa to the upper left thyroid lobe, leading to recurrent suppurative thyroiditis.5,6

Describe the Histologic Appearance, Embryologic Origin, and Classification of Other Common Developmental and Nondevelopmental Neck Masses

Epidermoid and dermoid cysts

Epidermoid and dermoid cysts are most commonly found in the midline of the neck. Epidermoid (inclusion) cysts are typically seen after puberty and in the acne-prone areas of the face and neck. They are lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium with a distinct granular layer. The cyst contains keratin debris or lamellated keratin (Figure 4C and D). The cyst wall of dermoid cysts also frequently contain adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, or eccrine glands.5,6

Epidermoid cysts originate from epidermal cells derived from ectodermal tissue that become trapped during closure of the first and second branchial arches during the third and fourth week of gestation. Alternatively, they may arise after inflammation or infection of a hair follicle.

Dermoid cysts are benign, developmental cysts that originate from the ectoderm and mesoderm, but not endoderm. They are thought to arise in embryonic suture lines as developmental invaginations of embryonic skin when migrating tissue is trapped in deeper planes. Another theory is that dermoid cysts are derived from anatomically isolated totipotential rests from the mesoderm and ectoderm that undergo disorganized growth.5,6

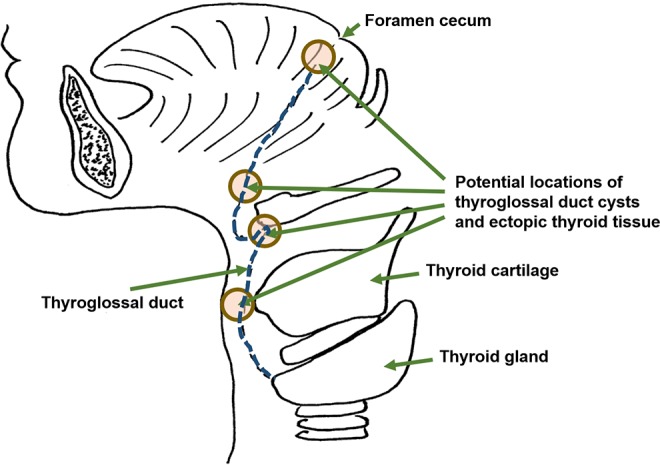

Thyroglossal duct cysts and ectopic thyroid

In contrast to branchial cleft cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts are located in the midline neck. Thyroglossal duct cysts are the most common congenital anomaly of the neck, and represent 70% of congenital neck masses. Due to the descent path of the thyroglossal duct, thyroglossal duct cysts are almost always connected to the hyoid bone. Thyroglossal duct cysts are usually asymptomatic midline neck masses that move upward when swallowing but could present clinically as a site of recurrent infections. Since they are almost always connected to the hyoid bone, removal of the hyoid bone is indicated when thyroglossal duct cysts are resected. The most characteristic histologic feature of thyroglossal duct cyst is the presence of cyst lining of pseudostratified, ciliated columnar and cuboidal epithelium, and/or transitional epithelium. Often, the cyst wall shows thyroid follicles (Figure 6A and B). Importantly, neuroendocrine C-cells are not found in thyroglossal duct cysts due to their embryologic derivation, which is different from thyroid follicular epithelial cells. The presence of thyroid tissue is generally found in >50% of cases and is dependent on specimen sampling.12 In rare cases, carcinomas can arise in thyroglossal duct cysts: thyroid carcinomas, most commonly papillary thyroid carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinomas arising from metaplastic columnar epithelial cells.13

Figure 6.

A and B, Thyroglossal duct cyst: ciliated columnar (respiratory) epithelium-lined cyst with the presence of thyroid tissue in the cyst wall (A: ×40 [inset: whole slide], B: ×200). C and D, Cervical thymic cyst: cyst lined by squamous, cuboidal, or columnar epithelium with the presence of thymic tissue containing lymphoid aggregates and Hassall corpuscles (D, black arrow and inset) in the cyst wall (C: ×40 [inset: whole slide], D: ×200 [inset: ×400]; hematoxylin and eosin staining).

A major differential diagnosis of thyroglossal duct cyst is ectopic thyroid. Also known as aberrant thyroid rests or thyroid heterotopia, these are almost exclusively seen in suprahyoid locations and usually located in or close to the midline. The most common site of thyroid ectopia is at the base of tongue (also called lingual thyroid), just deep to the foramen cecum (the embryological origin of developing thyroid follicles). However, it can also be found within skeletal muscle or adipose tissue of the cervical neck, in intrathymic locations, or in suprathyroidal sites. Similar to thyroglossal duct cysts, malignant thyroid neoplasms, such as papillary thyroid carcinoma or follicular carcinoma, may also arise from ectopic thyroid tissue. Histologically, ectopic thyroid consists of normal-appearing thyroid tissue with colloid-filled follicles. Importantly, in contrast to the normal thyroid, neuroendocrine C-cells are not identified. It is essential to distinguish ectopic thyroid tissue from metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma, particularly those found in lymph nodes and in older patients. Since the latter is much more common than ectopic thyroid tissue, any morphologic signs of malignancy, such as a desmoplastic response or cytologic evidence of malignancy, should prompt a diagnosis of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma until proven otherwise.14

Developmentally, thyroid follicular epithelium develops from the foramen cecum, which is located at the base of tongue. The developing thyroid then migrates down the midline in the caudad direction until it reaches the normal anatomic position at the midline cervical neck. This path of migration is also known as the thyroglossal duct (Figure 7). Failure of the thyroglossal duct to obliterate, which normally occurs by the sixth week of gestation, results in the development of thyroglossal duct cysts. Ectopic thyroid tissue can be found anywhere along the midline, descending from the foramen cecum to the cervical neck. Of note, thyroid neuroendocrine cells (C-cells) do not migrate in this fashion. Rather, C-cells originate from the neural crest and migrate to the ultimobranchial apparatus, which is located in the third to fourth branchial arches, and migrate only to the lateral lobes of thyroid glands. And thus C-cells or C-cell-related lesions, including medullary carcinomas, do not occur in either midline ectopic thyroid tissue or thyroglossal duct cysts.5,6

Figure 7.

The thyroglossal duct (blue dotted line) is the embryonic tract from the foramen cecum at the base of the tongue from which the developing thyroid gland descends to its destination in the neck. Shown are the various potential locations where both thyroglossal duct cysts and ectopic thyroid glands could arise when the thyroglossal duct fails to obliterate.

Cervical thymic cysts

Rarely, cystic neck masses can arise from cervical thymic cysts. Cervical thymic cysts are lateral neck masses, usually located anterior or deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, although they can be found anywhere between the angle of mandible and sternum, including the lateral and midline neck. Histologically, the cyst is lined by columnar, cuboidal, or squamous epithelium. The cystic wall by definition contains thymic tissue, consisting of lymphoid aggregates and Hassall corpuscles, which are concentric islands of squamous cells often with central keratinization (Figure 6C and D).

The thymus arises primarily from the third branchial pouch (mesoderm), and failure of the thymus to descend results in cervical thymic cysts, the majority of which occur during first decade of life. They can present as an isolated mass or in continuity with the intrathoracic thymus gland. The path of descent extends from the anterior mediastinum into the lower neck along the course of the thymopharyngeal duct, which is anatomically closely associated with the carotid space.5,6

Metastatic malignancies

The most important differential diagnosis of any squamous epithelium-lined cysts in the cervical neck is a metastatic malignancy, particularly in older patients, or patients with major risk factors, such as history of tobacco use. Metastatic cystic squamous cell carcinoma typically contains a very thick-walled capsule. The atypical epithelium lacks maturation and shows cellular enlargement, mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and tumor necrosis (Figure 8). Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is most often found in cervical lymph nodes. A high proportion of cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated squamous cell carcinoma. The most likely primary sites of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma are the tonsils and base of tongue, but in 30% of patients, the primary site of the tumor may never be identified.15

Figure 8.

Cystic squamous cell carcinoma: predominantly cystic structure with a dense, fibrous capsule, and a ribbon- or band-like, complex lining of thick squamous epithelium with frequent papillary folds or projections. The epithelial lining shows loss of maturation toward the cystic lumen, disorganization, high nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio, and pleomorphism. Nests of tumor cells are found within the cyst wall with central necrosis (×40; inset, ×200; hematoxylin and eosin staining).

Paraganglioma

Another noncystic neoplasm that could be seen in the head and neck is paragangliomas. Microscopically, the tumor cells are arranged in an organoid (Zellballen) pattern. They are typically composed of chief cells characterized by abundant pale cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, and spindle-shaped sustentacular cells located peripherally around the nests. A prominent vascular network usually separates tumor cell nests.

Paragangliomas are rare tumors that could be found throughout the body. In the head and neck, they could arise from the carotid body, vagal nerve, middle ear, and larynx. Paragangliomas are nonepithelial, neuroendocrine neoplasms that originate from neural crest–derived paraganglia of the parasympathetic nervous system. In contrast to pheochromocytomas of the adrenal gland and other extra-adrenal paragangliomas in the abdomen that often present with hypertension and tachycardia, paragangliomas of the head and neck are rarely functional.16 Other neck masses or structures that could be biopsied but are not cystic include lymph nodes, parathyroid glands, and rare tumors such as rhabdomyoma, the discussion of which is outside of the scope of this article.

Teaching Points

Although cytologic findings of neck masses can be nonspecific, the use of FNA and cytology is useful as a presurgical screening tool in neck masses to exclude malignancies, including metastatic cystic squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis of cystic neck masses is broad and includes branchial cleft cysts, epidermoid inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts, lymphoma, cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, and other metastatic malignancies.

Branchial cleft cysts account for 20% of all developmental cervical cysts and are usually located in the lateral neck near the mandibular angle.

Histologic features of branchial cleft cysts include a bland squamous-lined cyst with lymphoid-rich wall and variable inflammation.

Epidermoid (inclusion) cysts are typically lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium with a distinct granular layer, and the cyst contains keratin debris. Dermoid cysts are similar to epidermoid cysts but also contain adnexal structures in the cyst wall.

The most important differential diagnosis of a squamous-lined cyst is a metastatic cystic squamous cell carcinoma. Features suggestive of malignancy include nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear irregularity and hyperchromasia, mitotic figures, and tumor necrosis.

Thyroglossal duct cysts are the most common congenital anomaly of the neck and are found in the midline of the neck adjacent to the hyoid bone.

Histologic features of thyroglossal duct cysts include a respiratory epithelium-lined cyst with or without thyroid follicles in the cyst wall.

Ectopic thyroid tissue represents a failure from proper migration of thyroid follicles, and can be found anywhere along the midline from the foramen cecum to the cervical neck.

Histologic features of cervical thymic cysts consist of a cyst that is variably lined by columnar, cuboidal, or squamous epithelium, with thymic tissue within the cyst wall.

The thymus arises primarily from the third branchial pouch (mesoderm), and failure of a portion of the thymus to descend results in cervical thymic cysts.

Paragangliomas are rare tumors that could arise from the carotid body, vagal nerve, larynx, and middle ear in the head and neck.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Josephine Kamtai Dermawan  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1139-2914

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1139-2914

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology competencies for medical education and educational cases. Acad Pathol. 2017:4 doi:10.1177/2374289517715040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krane JF, Faquin WC. Salivary gland In: Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, eds. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 4th ed Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Layfield LJ, Esebua M, Schmidt RL. Cytologic separation of branchial cleft cyst from metastatic cystic squamous cell carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of nineteen cytomorphologic features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson LD, Heffner DK. The clinical importance of cystic squamous cell carcinomas in the neck: a study of 136 cases. Cancer. 1998;82:944–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goins MR, Beasley MS. Pediatric neck masses. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;24:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosa PA, Hirsch DL, Dierks EJ. Congenital neck masses. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slater J, Serpell JW, Woodruff S, Grodski S. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the preoperative investigation of branchial cysts. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Begbie F, Visvanathan V, Clark LJ. Fine needle aspiration cytology versus frozen section in branchial cleft cysts. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129:174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandanwale SS, Buch AC, Chawla KR, Mittal PU. Fine needle aspiration cytology of thyroglossal duct cyst: diagnostic pitfalls and a study of 14 cases. Thyroid Res Pract. 2013;10:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen KT. Cytology of thyroglossal cyst papillary carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:318–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson LD. Branchial cleft cyst. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei S, LiVolsi VA, Baloch ZW. Pathology of thyroglossal duct: an institutional experience. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Choi YM, Kim TY, Song DE, et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma arising from a thyroglossal duct cyst: a single institution experience. Endocr J. 2013;60:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. LiVolsi VA, Perzin KH, Savetsky L. Carcinoma arising in median ectopic thyroid (including thyroglossal duct tissue). Cancer. 1974;34:1303–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldenberg D, Sciubba J, Koch WM. Cystic metastasis from head and neck squamous cell cancer: a distinct disease variant? Head Neck. 2006;28:633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams MD. Paragangliomas of the head and neck: an overview from diagnosis to genetics. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:278–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]