Significance

Ubiquitination is a vital posttranslational modification in eukaryotes. A variety of microbial pathogens exploit this pathway during their infection. Legionella pneumophila, the causative bacterial pathogen of Legionnaires’ disease, has been shown to hijack host ubiquitination pathway via a large number of effectors. Recent studies revealed a family of effectors catalyzing a type of ubiquitin (Ub)-dependent posttranslational modification, namely PR-ubiquitination. Here we report 2 players, DupA and DupB, involved in this unconventional pathway. We found that DupA and DupB function as PR-Ub–specific deubiquitinases and play a role in regulating the PR-ubiquitination levels of host targets. Our results not only provide an expanding view of the PR-ubiquitination pathway, but also may facilitate the future identification of PR-ubiquitination pathways in eukaryotes.

Keywords: SidE, SdeA, ubiquitin, phosphoribosyl ubiquitination, deubiquitinase

Abstract

Posttranslational protein modification by ubiquitin (Ub) is a central eukaryotic mechanism that regulates a plethora of physiological processes. Recent studies unveiled an unconventional type of ubiquitination mediated by the SidE family of Legionella pneumophila effectors, such as SdeA, that catalyzes the conjugation of Ub to a serine residue of target proteins via a phosphoribosyl linker (hence named PR-ubiquitination). Comparable to the deubiquitinases in the canonical ubiquitination pathway, here we show that 2 paralogous Legionella effectors, Lpg2154 (DupA; deubiquitinase for PR-ubiquitination) and Lpg2509 (DupB), reverse PR-ubiquitination by specific removal of phosphoribosyl-Ub from substrates. Both DupA and DupB are fully capable of rescuing the Golgi fragmentation phenotype caused by exogenous expression of SdeA in mammalian cells. We further show that deletion of these 2 genes results in significant accumulation of PR-ubiquitinated species in host cells infected with Legionella. In addition, we have identified a list of specific PR-ubiquitinated host targets and show that DupA and DupB play a role in modulating the association of PR-ubiquitinated host targets with Legionella-containing vacuoles. Together, our data establish a complete PR-ubiquitination and deubiquitination cycle and demonstrate the intricate control that Legionella has over this unusual Ub-dependent posttranslational modification.

Ubiquitin (Ub), a 76-amino-acid protein, is attached to specific proteins as a potent posttranslational mechanism. Ubiquitination plays an essential role in a broad aspect of cellular processes, including protein homeostasis (1), cell signaling (2), and membrane trafficking (3, 4). Following the conventional scheme of ubiquitination, Ub is covalently coupled to lysine residues on target proteins via the sequential activities of a collection of enzymes known as E1, E2, and E3 (5). The C-terminal glycine residue of Ub is first activated and covalently linked to the catalytic cysteine residue of the Ub-activating enzyme E1 through a thioester bond with the consumption of an ATP. The activated Ub moiety is then transferred to the active site cysteine of an E2 Ub-conjugating enzyme. The resulting thioester-linked E2∼Ub complex interacts with specific E3 Ub ligases, which promote the direct or indirect transfer of Ub to the ε-amine of a lysine residue of substrates or Ub or the N-terminal amine of another Ub molecule (6–8).

Given the vital role of ubiquitination in cell physiology, it is not surprising that a variety of microbial pathogens exploit this essential posttranslational modification pathway during the infection of their corresponding hosts (9). For example, the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila injects more than 300 effector proteins into host cells via the Dot/Icm transporter (10, 11). Among the hundreds of L. pneumophila effectors, more than 10 proteins are involved in ubiquitin manipulation (10). These include proteins that contain the conserved eukaryotic F- or U-box domains found in some canonical E3 ubiquitin ligases (12–15). Other E3 Ub ligases that have a unique structural fold but similar catalytic chemistry to the HECT-type ligases have also been characterized (16–18). In addition to these Ub ligases, which utilize the canonical host Ub machinery for ubiquitination, recent studies of the L. pneumophila SidE family of effectors (SidEs), such as SdeA, uncovered a novel ubiquitination pathway that acts independently of E1 and E2 enzymes (19–21). Instead, this unusual SdeA-catalyzed ubiquitination involves both mono-ADP ribosyl transferase (mART) and phosphodiesterase (PDE) activities to PR-ubiquitinate substrates. SdeA first uses its mART domain to catalyze the transfer of ADP ribose from NAD+ to the residue R42 of Ub to generate mono-ADP ribosyl Ub (ADPR-Ub). Subsequently, via the activity of the PDE domain, ADPR-Ub can be conjugated to serine residues of substrate proteins to generate a serine-ubiquitinated product and release AMP (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, ADPR-Ub can be transferred to a water molecule to generate phosphoribosyl Ub (PR-Ub) in the absence of substrate proteins (22–26). Our previous data further showed that the mART and the PDE domain function independently and that the isolated PDE domain from SdeA is fully functional to PR-ubiquitinate substrates when ADPR-Ub is supplied (22).

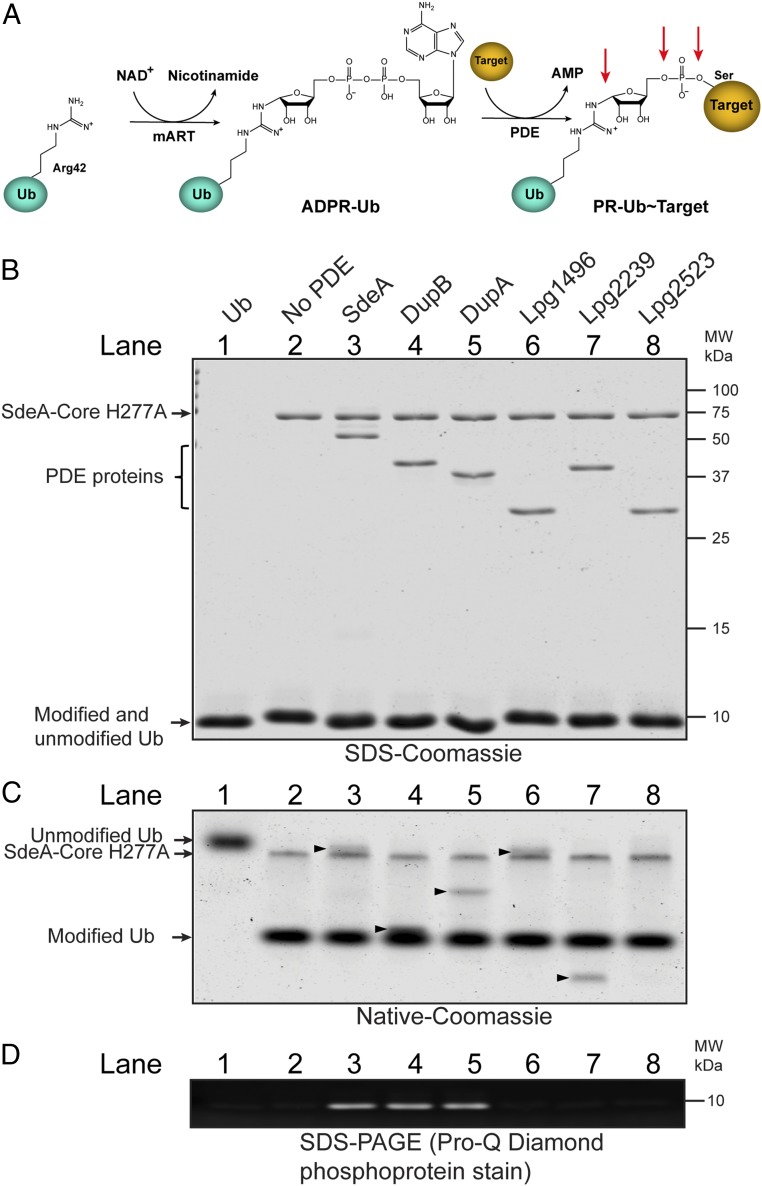

Fig. 1.

The PDE domains from DupA and DupB process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub. (A) Schematic view of the 2-step PR-ubiquitination reaction. The mART domain of SidEs catalyzes ADP ribosylation of residue R42 of Ub and the PDE domain conjugates PR-Ub to a serine residue of substrates. Possible cleavage sites by potential PR-Ub–specific DUBs are indicated by red arrows. (B) ADPR-Ub was first generated with SdeA-Core H277A and then mixed with the PDE domains from the indicated Legionella effectors. The final reaction mixtures were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. The SdeA-Core, PDE, and Ub proteins are indicated on the left side of the gel. (C) Native PAGE analysis of the final reaction mixtures. The modification of Ub was exhibited as the mobility shift of Ub species. The arrowheads mark the migration position of the PDE-domain proteins on the native gel. (D) The processing of ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub was detected by SDS/PAGE followed by Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining. The signals in lanes 3 to 5 indicate the production of PR-Ub.

The PDE domain of SdeA is conserved in 9 L. pneumophila effectors (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In addition to the 3 additional SdeA paralogs, SidE, SdeB, and SdeC, which have been shown to be PR-ubiquitination ligases, there are 5 other PDE-domain–containing effectors that lack an adjacent mART domain. Here we report that the latter 5 PDE-domain–containing proteins do not possess PR-Ub ligase activity, but surprisingly, Lpg2154 and Lpg2509 [previously named SdeD (27)], 2 highly homologous effectors with more than 70% sequence similarity, exhibit a robust activity to process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub and efficiently cleave PR-Ub from PR-ubiquitinated substrates. We thus renamed Lpg2154 and Lpg2509 as DupA (deubiquitinase for PR-ubiquitination) and DupB, respectively. We further show that DupA and DupB can rescue the dispersed Golgi phenotype caused by exogenous expression of SdeA in mammalian cells. Finally, we demonstrate that a strain lacking dupA and dupB markedly promotes the accumulation of PR-ubiquitinated species in host cells during infection. The presence of the 2 bona fide PR-Ub–specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) provides a potential regulatory mechanism for PR-ubiquitination in Legionella infection.

Results

Two PDE Domain-Containing Legionella Effectors Can Process ADPR-Ub to Generate PR-Ub.

Our previous studies have shown that the isolated PDE domain of SdeA is sufficient to PR-ubiquitinate substrates when purified ADPR-Ub is supplied (22). Since the PDE domain is conserved in a total of 9 effectors from the Philadelphia strain of Legionella pneumophila (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), we asked whether other PDE domains have PR-ubiquitination ligase activity similar to SdeA. To answer this question, we prepared recombinant proteins of the PDE domain from SdeA and 5 non-SidE family PDE-domain containing Legionella effectors. We then incubated the PDE-domain proteins with purified human influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ADPR-Ub and whole HEK293T cell lysates for 1 h at 37 °C to allow the PR-ubiquitination reaction to occur. PR-ubiquitinated species were generated in the reaction with the PDE domain of SdeA but not any other PDEs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Consistent with these results, only the SdeA PDE domain could PR-ubiquitinate Rab33b, a previously reported PR-ubiquitinated substrate (19) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Since the PDE domain of SdeA is able to cleave ADPR-Ub to generate PR-Ub and AMP in the absence of substrates (20, 22), we asked whether other PDE domains are also able to process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub. To address this question, we performed a 2-step reaction to track the modification of Ub. In this assay, ADPR-Ub was first generated with a SdeA fragment (SdeA-Core; amino acids 211 to 910) carrying the H277A mutation that lacks the PDE activity but has an intact mART activity. After the first step of the reaction, each PDE-domain protein was then added to the reaction to determine their ability to process ADPR-Ub. All of the proteins involved in the reactions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) (Fig. 1B). The modification of Ub was indicated by the mobility shift of modified Ub in native-PAGE (Fig. 1C), and the generation of PR-Ub was analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining, which specifically stains terminal phosphoryl groups (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, in addition to the PDE domain of SdeA (Fig. 1 A–C, lane 3), both PDE domains from Lpg2509 (DupB/SdeD) and Lpg2154 (DupA) were able to cleave ADPR-Ub to generate PR-Ub (Fig. 1 A–C, lane 4 and 5). In contrast, the PDE domains of Lpg1496, Lpg2239, and Lpg2523 were not able to hydrolyze ADPR-Ub (Fig. 1 A–C, lanes 6 to 8). These results demonstrate that the PDE domains of DupA and DupB are able to process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub, indicating that DupA and DupB may modulate the PR-ubiquitination pathway during Legionella infection.

DupA and DupB Are PR-Ubiquitination–Specific Deubiquitinases.

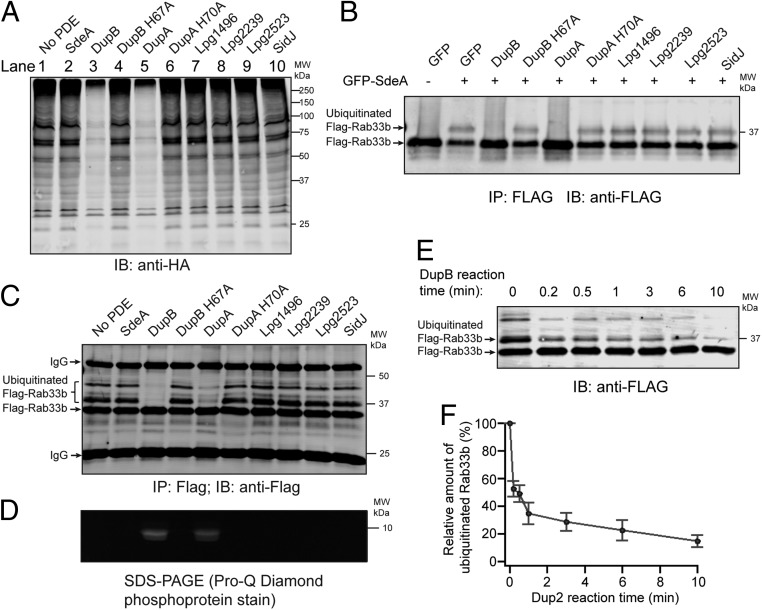

The cleavage of ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub by DupA and DupB led us to hypothesize that DupA and DupB may function as a deubiquitinase that specifically cleaves PR-Ub from PR-ubiquitinated substrates. To test this hypothesis, we incubated whole-cell lysates from HEK293T cells with recombinant HA-Ub, SdeA-Core, and NAD+ to generate PR-ubiquitinated substrates. The PR-ubiquitinated products were then incubated with the indicated wild type (WT) and catalytically inactive mutant PDE domains. Strikingly, PR-ubiquitination signals were markedly reduced after incubation with the WT PDE domains of DupA and DupB, but not their catalytically inactive mutants (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 to 6). By contrast, the PDE domain of SdeA did not reduce the PR-ubiquitination signal (Fig. 2A, lane 2) even though it can process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub (Fig. 1). Similar to SdeA, the other PDE-domain–containing effectors, Lpg1496, Lpg2239, and Lpg2523, showed no effect on the levels of PR-ubiquitinated substrates (Fig. 2A, lanes 7 to 9). Furthermore, the L. pneumophila effector SidJ, which was previously reported as a PR-Ub–specific DUB (28), showed no detectable changes of the PR-ubiquitinated signals when the PR-ubiquitinated substrate mixtures were incubated with purified recombinant SidJ and calmodulin since SidJ is activated by calmodulin (29) (Fig. 2A, lane 10). To further validate this ability, we examined whether DupA and DupB could process a PR-ubiquitinated protein when they were expressed within cells. PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b was processed only by WT DupA and DupB but not DupA or DupB catalytic mutants or other PDE-domain–containing proteins, including, once again, SidJ (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Finally, to address whether DupA and DupB can specifically process only PR-Ub conjugates but not conventional Ub conjugates, we prepared whole-cell lysates from cells expressing HA-Ub and then treated the lysates with the canonical N-terminal DUB domain of SdeA or the PDE-domain–containing proteins. The ubiquitination signals were drastically reduced in the presence of the SdeA DUB domain; however, no observable changes were detected in the presence of each PDE-domain–containing proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Together, these data demonstrate that DupA and DupB are bona fide PR-Ub–specific deubiquitinases.

Fig. 2.

DupA and DupB function as PR-Ub–specific deubiquitinases. (A) PR-ubiquitinated species were generated by incubating HEK293T cell lysates with HA-Ub, NAD+, and SdeA-Core. The PR-ubiquitinated products were then treated with recombinant proteins of the PDE domains from the indicated Legionella effectors or SidJ. The final reaction products were analyzed by Western blot against anti-HA. (B) 4xFlag-Rab33b and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-SdeA were coexpressed with EGFP-tagged full-length Legionella effectors in HEK293T cells. 4xFlag-Rab33b was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by Western blot with anti-Flag antibody. (C) Recombinant 4xFlag-Rab33b was PR-ubiquitinated by SdeA-Core and purified with anti-Flag beads. The bound proteins were then treated with the indicated recombinant PDE-domain proteins or SidJ, and the final products were analyzed by anti-Flag Western blot. (D) Pro-Q phosphoprotein staining of the final products from C to detect the generation of PR-Ub. (E) Reaction time course of the cleavage of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b by DupB. PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b was generated using 6xHis-sumo-SdeA-Core. After removal of 6xHis-sumo-SdeA-Core with cobalt beads, the supernatant was treated with 1 μM DupB PDE domain for the indicated period of time at 37 °C. At each time point, equal amounts of reaction volumes were mixed with SDS loading dye to stop the reaction and analyzed by anti-Flag Western blot. (F) Quantification of the cleavage of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b in E. The intensity of the remaining PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b at each reaction time point was normalized to the value at time 0. The error bars represent the SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Since PR-Ub is linked to a serine residue of substrates via a ribose and phosphate group (19–21), we next investigated which bond is cleaved by DupA and DupB and what products are generated after the cleavage (see potential cleavage sites in Fig. 1A). To address this question, we generated PR-ubiquitinated Flag-Rab33b using SdeA-Core and immobilized it (unmodified or in the PR-ubiquitinated form) onto beads conjugated with anti-Flag antibodies. The immunoprecipitated materials were then treated with PDE-domain proteins or SidJ. The final products were analyzed by an anti-Flag Western blot and Pro-Q diamond phosphoprotein stain. In agreement with our previous results, the amount of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b diminished after treatment with DupA and DupB, but not by their catalytically defective mutants or by any of the other PDE-domain proteins (Fig. 2C). Importantly, phosphoprotein signals were detected in samples treated with WT DupA or DupB and appeared at a band corresponding to the size of Ub, indicating the production of PR-Ub (Fig. 2D). Therefore, these results suggest that DupA and DupB cleave the phosphoester bond between the phosphate group and the hydroxyl group of the serine residue of the substrate to generate PR-Ub and unmodified substrates. The production of PR-Ub was further confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The cleavage of the phosphoester bond between the phosphate group and the hydroxyl group of the serine residue by DupA/DupB is also in agreement with our published crystal structure of the PDE domain of DupB in complex with ADPR-Ub, in which the β-phosphate group of ADPR-Ub is positioned and primed to be attached by the catalytic histidine (H67) to produce PR-Ub (22) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). To further investigate the PR-Ub DUB activity of DupA/DupB, we performed semiquantitative enzymatic assays by measuring the clearance rate of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b in the presence of the DupB PDE domain (Fig. 2E). The amount of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b was reduced to less than 50% within 1 min of reaction when treated with DupB at 1 µM of concentration (Fig. 2 E and F). However, the levels of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b remained unchanged when treated with the same amount of SdeA PDE or SidJ proteins under similar conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Together, these studies show that DupA and DupB but not SidJ function as PR-ubiquitination–specific deubiquitinases.

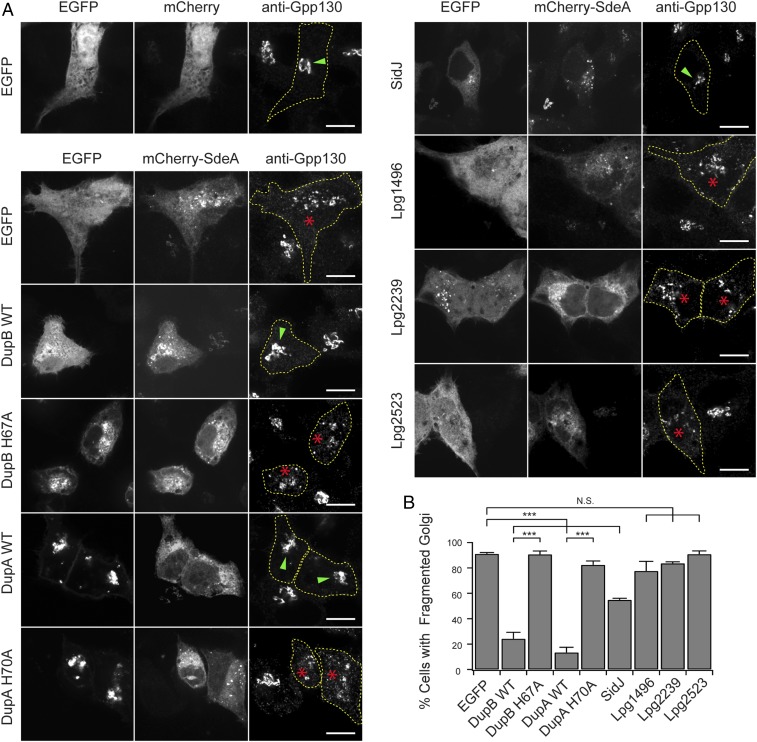

Golgi Fragmentation Caused by SdeA Can Be Suppressed by DupA and DupB.

It has been reported that exogenous expression of SdeA induces Golgi fragmentation in mammalian cells (30). We were able to recapitulate the dispersed Golgi phenotype in HeLa cells when WT full-length SdeA was expressed. Furthermore, we found that both the intact mART and the PDE activities were required to cause Golgi fragmentation since cells expressing the SdeA EE/AA (E860A/E862A) mutant, which is defective in mART activity, or the SdeA H277A mutant, which is defective in PDE activity, showed normal Golgi morphology (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). These observations suggest that the dispersed Golgi morphology is due to PR-ubiquitination of host proteins mediated by SdeA. The identification of DupA and DupB as PR-Ub–specific DUBs led us to hypothesize that DupA and DupB might be able to suppress the dispersed Golgi phenotype caused by SdeA. Indeed, the Golgi morphology was restored when SdeA- transfected cells were cotransfected with either mCherry-DupA or DupB, but not their PDE-defective mutants or other PDE-domain–containing effectors (Fig. 3). In agreement with previously reported results, the Golgi morphology was also rescued by cotransfection with the Legionella effector SidJ (Fig. 3). In summary, the dispersed Golgi caused by SdeA is likely due to PR-ubiquitination of host proteins, and either DupA or DupB can fully restore the Golgi morphology by its PR-Ub–specific DUB activity.

Fig. 3.

DupA and DupB rescue the dispersed Golgi phenotype caused by SdeA. (A) Representative images showing the Golgi morphology of HeLa cells coexpressing mCherry-SdeA and EGFP-tagged full-length Legionella effectors. Cells were fixed and immunostained with rabbit anti-Gpp130. For transfected cells, cell outlines are drawn with dashed lines and Golgi structures with normal stacked or dispersed morphology are indicated by green arrowheads or red stars, respectively. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) Percentage of cells showing dispersed Golgi for the cells expressing the indicated proteins. Data are shown as means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. At least 40 cells/condition were counted. ***P < 0.001, N.S., not significant.

DupA and DupB Do Not Suppress SdeA Toxicity in Yeast.

Previously, it was shown that expression of SdeA in yeast strongly inhibits its growth (19, 30–33). Inhibition by SdeA requires its mART activity since the SdeA mART mutant (SdeA EE/AA) is no longer toxic. In contrast, SdeA’s DUB and PDE activities are not required for toxicity as a SdeA DUB mutant (SdeA C118A) and a SdeA PDE mutant (SdeA H277A) remain inhibitory (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A–C). Expression of the Legionella effector SidJ, which is a negative regulator of SdeA activity, was able to suppress SdeA toxicity when the proteins were coexpressed (SI Appendix, Fig. S9D) (28, 30). As a result, we inquired whether DupA or DupB could similarly alleviate the toxicity of SdeA in yeast. To test this hypothesis, SidJ, DupA, and DupB were coexpressed in yeast with SdeA (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 D and E). Surprisingly, in contrast to SidJ, coexpression of DupA or DupB using either the CYC or GAL promotors could not suppress the toxicity of SdeA (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 D and E and S10). Therefore, even though DupA and DupB are bona fide PR-Ub–specific DUBs, they are unable to block toxicity of SdeA in yeast, suggesting a mechanistic difference between DupA/DupB and SidJ (discussed further below).

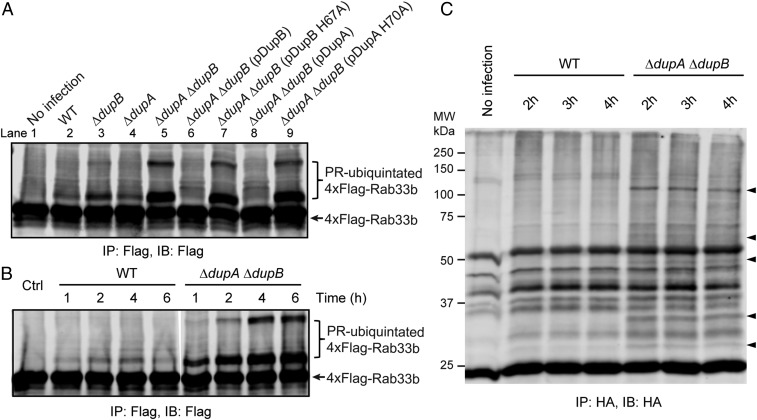

DupA and DupB Regulate PR-Ubiquitination of Host Targets in Legionella Infection.

To test if DupA and DupB function as PR-Ub–specific DUBs during intracellular infection by L. pneumophila, we created ΔdupA, ΔdupB, and ΔdupA ΔdupB double-deletion mutants and confirmed that dupA deletion does not interfere with the expression of sidJ, which is situated next to dupA in the L. pneumophila genome (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). We theorized that the absence of DupA and/or DupB would result in the overaccumulation of PR-ubiquitinated proteins during an infection. As predicted, infection of ΔdupA or ΔdupB single-knockout strains resulted in a modest increase in PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b in HEK293T cells whereas substantially more PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b accumulated using the ΔdupA ΔdupB double-knockout strain (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 5). This effect was due to the absence of DupA and DupB as the double-mutant could be complemented by expression of WT DupA or DupB, but not their catalytic mutants (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 to 9). Furthermore, the levels of PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b remained low up to 6 h post infection in the WT strain while the PR-ubiquitinated Rab33b levels increased dramatically in the ΔdupA ΔdupB mutant over the same time frame of infection (Fig. 4B). The elevated levels of PR-ubiquitinated substrates were not limited to the exogenously overexpressed substrate Rab33b. The enhancement of PR-ubiquitination of endogenous host proteins was also evident in cells infected with the ΔdupA ΔdupB strain (Fig. 4C). These results convincingly demonstrate that DupA and DupB play a role in regulating the PR-ubiquitination of host targets during Legionella infection. We next asked whether the deletion of these 2 PR-Ub–specific DUBs has an effect on Legionella intracellular growth. Unlike the ∆sidJ mutant, the ∆dupA ∆dupB mutant does not have a significant growth defect on its own within Acanthamoebae castellanii. However, similar to what was previously seen with a ∆sidJ mutant (30), the growth of the ∆dupA ∆dupB mutant was inhibited by overexpression of SdeA (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). These data suggest a mechanistic distinction between DupA/DupB and SidJ and further support a role of DupA and DupB in regulating the PR-ubiquitination pathway.

Fig. 4.

DupA and DupB regulate PR-ubiquitination of host targets during Legionella infection. (A) HEK293T cells expressing 4xFlag-Rab33b were infected with relevant L. pneumophila strains for 2 h. Rab33b proteins were enriched by anti-Flag immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-Flag Western blot. (B) HEK293T cells expressing 4xFlag-Rab33b were challenged with either the WT or the ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella strain for the indicated periods of time, and Rab33b proteins were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by anti-Flag Western blot. (C) HEK293T cells expressing HA-Ub G76A were infected with WT or ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella strains. PR-ubiquitinated host proteins were enriched by anti-HA immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-HA Western blot. Specific bands detected during infection the by ΔdupA ΔdupB strain are marked by arrowheads. For all of the infection experiments, cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing FcγRII, and the Legionella bacteria were opsonized by polyclonal anti-Legionella antibody prior to infection.

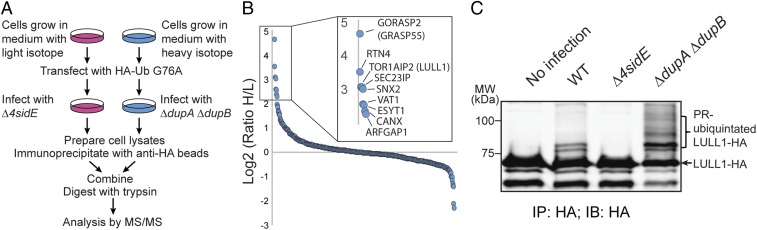

Identification of PR-Ubiquitinated Host Targets in Legionella Infection.

The increased levels of PR-ubiquitinated proteins during an infection with the ΔdupA ΔdupB mutant provided us with the opportunity to identify PR-ubiquitinated host targets via a SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture) approach (Fig. 5A). In this approach we employed a Ub mutant, HA-Ub G76A, as it has a decreased propensity to be used in the conventional Ub pathway, but can be used in the PR-ubiquitination pathway due to its intact residue R42. We transformed HEK293T cells with HA-Ub G76A and then challenged the cells grown in medium containing light-isotope–labeled Arg/Lys with the Δ4sidE strain, which lacks all 4 members of the SidE family, and cells grown in medium containing heavy-isotope–labeled Arg/Lys with the ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella strain for 2 h. Cell lysates were prepared, treated, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 5A). Applying these strategies, we identified a list of potential host PR-ubiquitination targets by mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 5B and Dataset S1). In agreement with a previous publication (21), we identified the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein Rtn4 as a PR-ubiquitinated protein. Other substrates included GORASP2 (Golgi reassembly-stacking protein 2, also named GRASP55) and TOR1AIP2 (Torsin-1A–interacting protein 2, also named LULL1). GRASP55 is a Golgi and ER membrane localized protein and plays a role in membrane stacking of Golgi cisternae (34, 35) or in regulating an unconventional ER-stress–induced secretory pathway (36). The other protein, LULL1, is an ER membrane protein regulating the activity and distribution of an AAA family ATPase, Torsin 1A, between ER and the nuclear envelope (37, 38). We validated this approach using both GRASP55 and LULL1. PR-ubiquitinated LULL1 could be detected in cells infected with the WT L. pneumophila strain Lp02, and a more robust signal was observed in cells infected with the ΔdupA ΔdupB mutant. However, no PR-ubiquitinated LULL1 was detected in cells in the absence of infection or cells infected with the Δ4sidE Legionella strain, which lacks PR-ubiquitination activity (Fig. 5C). Similarly, PR-ubiquitinated GRASP55 was also confirmed in cells infected with WT L. pneumophila strain Lp02 and the ΔdupA ΔdupB mutant but not the Δ4sidE mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S13A). Thus, this approach has revealed with high confidence a set of host targets that are PR-ubiquitinated during Legionella infection.

Fig. 5.

Proteomic identification of host PR-ubiquitination targets. (A) Experimental flowchart of SILAC sample preparation. (B) MS/MS analysis of SILAC samples prepared from cells expressing HA-Ub G76A and infected with either Δ4sidE (light, L) or ΔdupA ΔdupB (heavy, H) strain. The geometric mean of heavy/light peptide ratios for all detected proteins are plotted from left to right in descending order. For a protein to be considered in the plot, it required SILAC quantification from at least 6 independent peptide identifications. (C) Confirmation of PR-ubiquitinated host targets. HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing LULL1-HA and then infected with relevant Legionella strains for 2 h. LULL1 was enriched by anti-HA immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-HA Western blot.

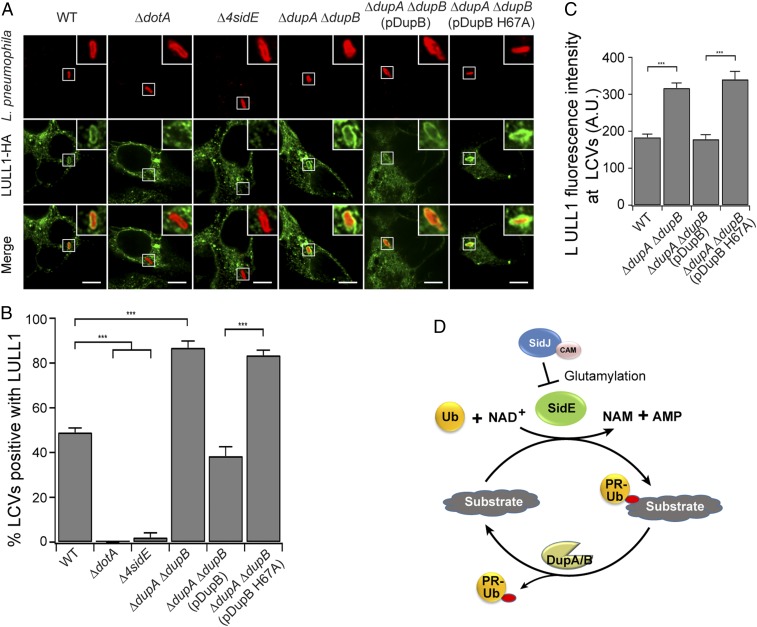

DupA and DupB Modulate the Recruitment of PR-Ubiquitinated Host Proteins to Legionella-Containing Vacuoles.

Since PR-ubiquitinated Rtn4 was recruited to the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) and the Rtn4-LCV association depended on the PR-ubiquitination activity of SidEs (21, 39), we hypothesized that other PR-ubiquitinated host substrates may also be recruited to the LCV. We tested this hypothesis by examining the location of LULL1-HA and GRASP55-HA in HEK293T cells infected with several different Legionella strains. In cells infected with WT L. pneumophila, 49% of the LCVs were positive for LULL1 2 h post infection (Fig. 6 A and B). In contrast, LULL1 LCV recruitment did not occur with a Dot/Icm-deficient strain or the Δ4sidE strain. However, the association of LULL1 with the LCVs was nearly doubled in cells challenged with the ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella strain. Importantly, enhanced LULL1 association did not occur when the ΔdupA ΔdupB mutant was complemented with WT DupB but remained at high levels in cells expressing the DupB catalytically inactive H67A mutant (Fig. 6 A and B). Interestingly, quantitative analysis of LULL1 signals at the LCV revealed that the fluorescence intensity of LCV-associated LULL1 was nearly doubled in cells infected with the ΔdupA ΔdupB or the ΔdupA ΔdupB + pDupB H67A strain compared to that in cells infected with the WT or the ΔdupA ΔdupB + pDupB strain (Fig. 6C). This observation is apparently in agreement with increased levels of PR-ubiquitination substrates in cells infected with the ΔdupA ΔdupB strain (Fig. 4). Furthermore, as expected, we also observed a similar pattern of GRASP55 recruitment to the LCV in cells upon Legionella infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 B–D). Therefore, PR-ubiquitination of more than one protein results in LCV association during an infection, and the PR-Ub DUB activity of DupA and DupB plays a role in modulating the accumulation of PR-ubiquitinated host targets to the bacterial phagosome.

Fig. 6.

PR-ubiquitination of LULL1 facilitates its recruitment to the LCV. (A) Representative confocal images show the recruitment of LULL1 (green) in HEK293T cells challenged with specified Legionella strains (red) for 2 h. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of LULL1-positive LCVs in cells infected with the indicated Legionella strains. Data are shown as means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. More than 80 LCVs were counted for each condition. ***P < 0.001. (C) Quantitative analysis of the LULL1 fluorescence intensity associated with the LCV. Data are shown as means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The value was averaged from more than 35 LULL1-positve LCVs for each condition. ***P < 0.001. (D) Schematic model of the PR-ubiquitination and deubiquitination cycle. The SidE family PR-Ub ligases catalyze PR-ubiquitination while DupA and DupB catalyze the removal of PR-Ub from substrates. The effector SidJ inhibits the mART activity of SidE ligases by polyglutamylation modification of SidE family ligases in a calmodulin (CAM)-dependent manner.

Discussion

In our search for additional PR-ubiquitination ligases among Legionella effectors, we discovered 2 PDE-domain–containing effectors, DupA (Lpg2154) and DupB (Lpg2509), that function as PR-Ub–specific deubiquitinase. We showed that DupA and DupB can specifically process ADPR-Ub to PR-Ub and can deubiquitinate PR-ubiquitinated substrates to release PR-Ub and unmodified substrates. We also demonstrated that DupA and DupB are capable of rescuing the Golgi fragmentation phenotype caused by exogenous expression of SdeA in mammalian cells and can modulate the levels of PR-ubiquitination of endogenous host targets during infection. Our findings establish a complete PR-ubiquitination and deubiquitination cycle, in which the SidE family effectors catalyze the ligation of PR-Ub to substrates while DupA and DupB deubiquitinate PR-Ub from modified substrates.

Although we convincingly demonstrated that DupA and DupB function as PR-Ub–specific DUBs, a recent study reported that the effector SidJ catalyzes the same PR-Ub deubiquitination reaction (28). However, in contrast to this earlier report, we have been unable to detect this activity for SidJ. Consistent with our observed functional differences between SidJ and DupA/DupB, expression of SidJ, but not DupA or DupB, is able to suppress SidE-mediated yeast toxicity (30, 31, 40). This is notable as SdeA yeast toxicity can be recapitulated with the SdeA H277A mutant, which generates ADPR-Ub through its intact mART domain but lacks the PR-Ub ligase activity. As a result, yeast toxicity is not caused by PR-ubiquitination of host proteins but instead is likely due to the accumulation of ADPR-Ub or PR-Ub or depletion of Ub in yeast. Therefore, the most parsimonious explanation is that SidJ has an activity other than as a PR-Ub DUB. Indeed, 4 recent publications reported that SidJ is a polyglutamylase that attaches glutamate residues to SidE family ligases and thus inhibits the mART activity of the ligases (29, 41–43). Although it is now confirmed that DupA/DupB and SidJ catalyze completely different reactions, it is worth noting that dupA (lpg2154) is encoded adjacent to sidJ (lpg2155) whereas dupB (lpg2509) is encoded next to the sidJ paralog sdjA (lpg2508). How the activity and specificity of these 2 loci (dupA-sidJ and dupB-sdjA) have diverged since their duplication is an interesting topic for future experimental interrogation.

Our results on DupA/DupB, as well as recently published data on SidJ, has revealed additional regulatory layers for how Legionella controls the PR-ubiquitination cycle during an infection (Fig. 6C). The various PR-Ub ligases (SidE, SdeA, SdeB, SdeC) presumably have different targets with the host cell, and we speculate that the initial PR-ubiquitination triggered by these factors is important for the bacterium to establish a proper niche for intracellular growth. However, unregulated modification of the PR-Ub ligase targets is toxic to the cell and therefore must be restricted. DupA and DupB likely function at an early stage of infection and persist at later time points to limit excessive PR-ubiquitination by the cleavage of PR-Ub from target proteins. This theorem is supported by the observation of the enhancement of PR-ubiquitinated substrates as early as 1 h and up to 6 h post infection with the ΔdupA ∆dupB strain (Fig. 4B). At a later point in the infection, SidJ directly suppresses the activity of SidE ligases through polyglutamylation of the ligases after they are no longer needed consistent with the previously published observation that SidJ regulates the disappearance of SidE proteins from the LCV (30). Thus, PR-ubiquitination is tightly regulated through concerted actions of PR-Ub–specific DUBs and PR-Ub ligase suppressors.

Since all of the PDE domains from L. pneumophila effectors have a similar structural fold and nearly identical catalytic residues, it is puzzling that the PDE domains of the SidE proteins function as a PR-Ub ligase, whereas the PDEs domains of DupA and DupB deconjugate PR-ubiquitinated substrates. One possible explanation is that the SdeA PDE domain showed no detectable interaction with Ub in solution, while the DupB PDE domain exhibited a direct and specific interaction with Ub as revealed by our previous NMR chemical shift titration experiments (22). As a result, it is possible that the differential Ub-binding affinity of the PDE domains determines whether they act as a ligase or a DUB. In the case of SdeA, its PDE domain might bind ADPR-Ub, primarily due to the interaction with the ADPR moiety. However, its low Ub-binding affinity prohibits its binding with PR-ubiquitinated substrates, and thus the PDE domain of SdeA can function only as a ligase but not a PR-Ub DUB. On the other hand, the PDE domains of DupA/DupB have a high affinity for Ub, which allows high affinity binding with both ADPR-Ub and PR-ubiquitinated substrates, thereby mediating their PR-Ub DUB activity. Nevertheless, future structural and biochemical studies will be required to resolve the molecular mechanism of different PDE domains.

Finally, by using the ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella mutant, we were able to identify additional host PR-ubiquitinated substrates with a SILAC approach and demonstrate that modified LULL1 and GRASP55 were recruited to the LCV. Interestingly, many of the top hits are proteins localized on the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, or intermediate transport vesicles between these membrane-bound organelles. This is consistent with the previous observation that PR-ubiquitination of Rtn4 is required for its recruitment to the LCV (21). Therefore, PR-ubiquitination may play a key role in the hijacking host endomembrane system during the maturation of bacteria-containing vacuoles. Another interesting finding of our SILAC experiment is that quite a few proteins involved in canonical ubiquitination pathways are also among the top hits of the list. These proteins include the Ub-activating enzyme E1, UBA1; the Ub-conjugating enzyme E2s, UBE2L3 and UBE2; several Ub E3 ligases; and the Ub adaptor proteins, Bag6 and p62/SQSTM1. Although these targets have yet to be confirmed under infection conditions, we speculate that PR-ubiquitination of these proteins may inhibit host endogenous ubiquitination pathways and thus may interfere with some Ub-dependent cellular process, such as autophagy, for the establishment of bacteria-containing vacuoles. In addition, it is plausible that inhibition of host endogenous ubiquitination pathways diverts additional free Ub for usage by the SidE family PR-Ub ligases. The exact biological consequence of PR-ubiquitination remains largely unknown; nevertheless, the list of potential PR-ubiquitinated substrates generated by using the ΔdupA ΔdupB Legionella mutant will certainly serve as a stepping stone for future investigations of this unusual type of Ub-dependent posttranslational modification.

To date, the PR-ubiquitination pathway is found only in Legionella species. It remains a fascinating question whether other organisms, particularly eukaryotes, encode a similar unique Ub-dependent posttranslational modification mechanism. The identification of 2 PR-Ub–specific DUBs not only completes the components involved in the PR-ubiquitination pathway but also provides key tools to probe for PR-ubiquitinated proteins and may facilitate the identification of PR-ubiquitination pathways in other organisms.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods are described at length in SI Appendix, Supplemental Materials and Methods. This includes cloning, site-directed mutagenesis, expression and purification of recombinant proteins, in vitro PR-ubiquitination assays, Legionella infection analyses, SILAC experiments, and immunofluorescence imaging.

Data Availability.

All DNA plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhao-Qing Luo (Purdue University) for Legionella strains and antibodies; Dr. Anthony Bretscher (Cornell University) for yeast strains, plasmids, and confocal microscope support; and Dr. William Brown (Cornell University) for antibodies. This work was supported by NIH Grants 5R01GM116964 (to Y.M.) and R01GM097272 (to M.B.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1916287116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover A., Varshavsky A., Basic medical research award. The ubiquitin system. Nat. Med. 6, 1073–1081 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z. J., Sun L. J., Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol. Cell 33, 275–286 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurley J. H., Stenmark H., Molecular mechanisms of ubiquitin-dependent membrane traffic. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40, 119–142 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haglund K., Dikic I., The role of ubiquitylation in receptor endocytosis and endosomal sorting. J. Cell Sci. 125, 265–275 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffner M., Nuber U., Huibregtse J. M., Protein ubiquitination involving an E1-E2-E3 enzyme ubiquitin thioester cascade. Nature 373, 81–83 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huibregtse J. M., Scheffner M., Beaudenon S., Howley P. M., A family of proteins structurally and functionally related to the E6-AP ubiquitin-protein ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 2563–2567 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel D. M., Lissounov A., Brzovic P. S., Klevit R. E., UBCH7 reactivity profile reveals parkin and HHARI to be RING/HECT hybrids. Nature 474, 105–108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciechanover A., Ben-Saadon R., N-terminal ubiquitination: More protein substrates join in. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 103–106 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin Y. H., Machner M. P., Exploitation of the host cell ubiquitin machinery by microbial effector proteins. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1985–1996 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu J., Luo Z. Q., Legionella and Coxiella effectors: Strength in diversity and activity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 591–605 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Best A., Abu Kwaik Y., Evolution of the arsenal of Legionella pneumophila effectors to modulate protist hosts. MBio 9, e01313–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price C. T., et al. , Molecular mimicry by an F-box effector of Legionella pneumophila hijacks a conserved polyubiquitination machinery within macrophages and protozoa. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000704 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubori T., Hyakutake A., Nagai H., Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 1307–1319 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubori T., Shinzawa N., Kanuka H., Nagai H., Legionella metaeffector exploits host proteasome to temporally regulate cognate effector. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001216 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ensminger A. W., Isberg R. R., E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and targeting of BAT3 by multiple Legionella pneumophila translocated substrates. Infect. Immun. 78, 3905–3919 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu F., et al. , The Legionella effector SidC defines a unique family of ubiquitin ligases important for bacterial phagosomal remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 10538–10543 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo X., et al. , Structure of the Legionella virulence factor, SidC reveals a unique PI(4)P-specific binding domain essential for its targeting to the bacterial phagosome. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004965 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Y. H., et al. , RavN is a member of a previously unrecognized group of Legionella pneumophila E3 ubiquitin ligases. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006897 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu J., et al. , Ubiquitination independent of E1 and E2 enzymes by bacterial effectors. Nature 533, 120–124 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhogaraju S., et al. , Phosphoribosylation of ubiquitin promotes serine ubiquitination and impairs conventional ubiquitination. Cell 167, 1636–1649.e13 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotewicz K. M., et al. , A single Legionella effector catalyzes a multistep ubiquitination pathway to rearrange tubular endoplasmic reticulum for replication. Cell Host Microbe 21, 169–181 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akturk A., et al. , Mechanism of phosphoribosyl-ubiquitination mediated by a single Legionella effector. Nature 557, 729–733 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong Y., et al. , Structural basis of ubiquitin modification by the Legionella effector SdeA. Nature 557, 674–678 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalayil S., et al. , Insights into catalysis and function of phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination. Nature 557, 734–738 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., et al. , Structural insights into non-canonical ubiquitination catalyzed by SidE. Cell 173, 1231–1243.e16 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim L., et al. , Structural and biochemical study of the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase domain of SdeA, a ubiquitylating/deubiquitylating enzyme from Legionella pneumophila. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2843–2856 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo Z. Q., Isberg R. R., Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 841–846 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu J., et al. , A unique deubiquitinase that deconjugates phosphoribosyl-linked protein ubiquitination. Cell Res. 27, 865–881 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black M. H., et al. , Bacterial pseudokinase catalyzes protein polyglutamylation to inhibit the SidE-family ubiquitin ligases. Science 364, 787–792 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong K. C., Sexton J. A., Vogel J. P., Spatiotemporal regulation of a Legionella pneumophila T4SS substrate by the metaeffector SidJ. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Havey J. C., Roy C. R., Toxicity and SidJ-mediated suppression of toxicity require distinct regions in the SidE family of Legionella pneumophila effectors. Infect. Immun. 83, 3506–3514 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campodonico E. M., Chesnel L., Roy C. R., A yeast genetic system for the identification and characterization of substrate proteins transferred into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 918–933 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidtman M., Chen E. J., Moy M. Y., Isberg R. R., Large-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates that modulate host cell vesicle trafficking pathways. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 230–248 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shorter J., et al. , GRASP55, a second mammalian GRASP protein involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae in a cell-free system. EMBO J. 18, 4949–4960 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barr F. A., Puype M., Vandekerckhove J., Warren G., GRASP65, a protein involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae. Cell 91, 253–262 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gee H. Y., Noh S. H., Tang B. L., Kim K. H., Lee M. G., Rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking via a GRASP-dependent unconventional secretion pathway. Cell 146, 746–760 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vander Heyden A. B., Naismith T. V., Snapp E. L., Hodzic D., Hanson P. I., LULL1 retargets TorsinA to the nuclear envelope revealing an activity that is impaired by the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2661–2672 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao C., Brown R. S., Chase A. R., Eisele M. R., Schlieker C., Regulation of Torsin ATPases by LAP1 and LULL1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E1545–E1554 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haenssler E., Ramabhadran V., Murphy C. S., Heidtman M. I., Isberg R. R., Endoplasmic reticulum tubule protein reticulon 4 associates with the Legionella pneumophila vacuole and with translocated substrate Ceg9. Infect. Immun. 83, 3479–3489 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urbanus M. L., et al. , Diverse mechanisms of metaeffector activity in an intracellular bacterial pathogen, Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Syst. Biol. 12, 893 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhogaraju S., et al. , Inhibition of bacterial ubiquitin ligases by SidJ-calmodulin catalysed glutamylation. Nature 572, 382–386 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gan N., et al. , Regulation of phosphoribosyl ubiquitination by a calmodulin-dependent glutamylase. Nature 572, 387–391 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sulpizio A., et al. , Protein polyglutamylation catalyzed by the bacterial calmodulin-dependent pseudokinase SidJ. bioRxiv, 10.1101/738567 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All DNA plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study are available upon request.