Abstract

Previous studies have reported that microRNA-133a (miR-133a) is involved in the pathogenesis of human cancers. This study investigated the effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The expression of miR-133a and YES proto-oncogene 1 (YES1) was detected using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay. The CCK-8 assay was used to measure cell proliferation. The relationship between miR-133a and YES1 was confirmed by dual luciferase assay. Downregulation of miR-133a was identified in NSCLC and correlated with poor prognosis in NSCLC patients. Moreover, the overexpression of miR-133a inhibited proliferation of NSCLC cells. YES1 was also confirmed as a direct target of miR-133a. Downregulation of YES1 was found to inhibit cell proliferation in NSCLC. By contrast, the upregulation of YES1 abolished the inhibitory effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation in NSCLC. miR-133a inhibited cell proliferation in NSCLC by targeting YES1, indicating that miR-133a can be used as an indicator of prognosis in NSCLC patients.

Keywords: miR-133a, non-small-cell lung cancer, YES1, proliferation, prognosis

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world, including small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). NSCLC includes squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. Compared with small cell carcinoma, NSCLC cells grow slowly and have a relatively slow diffusion and metastasis (1). In the past 50 years, many countries have reported a significant increase in incidence and mortality of lung cancer. However, the cause of lung cancer is still unclear to a certain extent. It has been shown that long-term heavy smoking is closely related to the occurrence of lung cancer (2). Moreover, 80–85% of lung cancer is NSCLC. Postoperative recurrence of NSCLC is the most prominent feature of treatment (3). Poor prognosis is also an important feature in patients with advanced NSCLC (4). Therefore, early detection, diagnosis and treatment are the key to improving the cure rate of NSCLC.

Different functions of microRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified in human cancers, including NSCLC. For example, miR-598 suppressed migration and invasion by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and Derlin-1 in NSCLC (5). miR-550a-3p promoted proliferation and metastasis of NSCLC cells by downregulating TIMP2 (6). Recently, miR-133a, a type of non-coding RNA, was demonstrated to function as gene expression regulators involved in tumorigenesis of human cancers. For example, the inhibitory effect of miR-133a was identified in gallbladder carcinoma (7). Moreover, it was reported that the low expression of miR-133a was associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer (8). In addition, the low expression of miR-133a was found to predict poor prognosis in NSCLC patients (9). Moreover, previous studies have shown that miR-133a exerts its effects by regulating the expression of target genes, such as USP39 (10). However, the regulatory mechanism of miR-133a remains unclear in NSCLC. Therefore, the role and target gene of miR-133a was explored in NSCLC.

As a prominent member of Src family tyrosinekinases (SFKs), YES proto-oncogene 1 (YES1) is a key regulator for tumor growth (11). It was reported that the important role of YES1 is also involved in the development of human cancers. Inhibition of YES1 restrained the migration, invasion and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells (12). Moreover, YES1 was identified as a central mediator of cell growth in malignant mesothelioma (13). Additionally, YES1 has been found to play an important role in the nuclear translocation of epidermal growth factor receptor (14). Seki et al (15) proposed that YES1 functioned as a proto-oncogene in primary human gastric cancer. In NSCLC, the function of YES1 and the interaction with miR-133a are ambiguous.

This study focused on measuring the abnormal expression of miR-133a and analyzing the prognostic relevance of miR-133a in NSCLC. In addition, the effect of miR-133a on the proliferation of NSCLC cells was also investigated. Furthermore, the relationship between miR-133a and YES1 was verified. This study will help us better understand the molecular mechanism of miR-133a in NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Clinical tissues

Fifty-two human NSCLC tissues and adjacent normal lung tissues (from patients with lung adenocarcinoma) were obtained from The Affiliated Zhuzhou Hospital of Xiangya Medical College CSU (Zhuzhou, China). NSCLC patients provided informed consent and received no other treatment except surgery. Each sample was confirmed by histopathological evaluation using hematoxylin and eosin staining. Clinical data were recorded at the time of resection and patients were prospectively followed-up to ascertain vital status. The tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C in a refrigerator. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Zhuzhou Hospital of Xiangya Medical College CSU.

Cell line culture

Normal human bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (ATCC® CRL-9609™) and H1299 (ATCC® CRL-5803™), A549 (ATCC® CCL-185™) NSCLC cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas). The cells were then seeded in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 24 h. In addition, 293 cells (BNCC100530, BNCC) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientifc, Inc.) and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Cell transfection

miR-133a mimics (forward, 5′-UUUGGUCCCCUUCAACCAGCUG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCUGGUUGAAGGGGACCAAAUU-3′) or inhibitor (5′-CAGCUGGUUGAAGGGGACCAAA-3′) and the negative control (miR-NC forward, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′) were obtained from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). YES1 siRNA (5′-ACTCAGGAATCGGCTCTGGAA-3′) and scramble siRNA (si-NC, 5′-GACCTGTACGCCAACACAGTG-3′) were also obtained from GenePharma. They were then transferred to A549 and H1299 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively, according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Plasmid constructs

For the overexpression of YES1, the primers used for amplification were: YES1 forward, 5′-GCGGGTACCATGGGCTGCATTAAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGCCTCGAGTTATAAATTTTCTCCTGGCT-3′. The YES1 cDNA products were cloned into the mammalian expression pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) at sites ‘KpnI and XhoI’ (Takara). Next, the vector was transfected into A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 h.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA in NSCLC tissues and cell lines was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent kit (DRR037A; Takara). We performed RT-qPCR using SYBR-Premix Ex Taq™ II (DRR041A; Takara) on the ABI 7300 HT Sequence Detection System (Biosystems). The cycling conditions were: 95°C for 15 sec, then 40 cycles at the following conditions: 94°C for 15 sec, 56°C for 15 sec, 66°C for 30 sec. The normalization of miRNA and mRNA was U6 and GAPDH, respectively. U6 was used for the normalization of miR-133a. GAPDH was used for the normalization of YES1. The expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆cq method (16). All RT-qPCRs were run in triplicate. The specific primer pairs used were: miR-133a forward, 5′-TGCTTTGCTAGAGCTGGTAAAATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCTACAGCTGGTTGAAGGG-3′; U6 forward, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′; YES1 forward, 5′-TCCAGAACTTTTTCACTTCAGTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTACATTTTCCTCTCTGTTCATC-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′.

CCK-8 assay

CCK-8 assay was performed to measure cell proliferation based on the manufacturer's instructions. Next, 5×104 NSCLC cells were incubated in 96-well plates for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h at 37°C. They were placed in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 reagents (Dojindo) were added to incubate the cells for 2 h. Finally, the cells were detected using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at an absorbance of 450 nm. All experiments were run in triplicate.

Bioinformatics analysis

Bioinformatics prediction TargetScan version 7.1 online software (www.targetscan.org) was used to predict the potential targets of miR-133a, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, human was selected as the target species and miR-133a was inserted as the investigated miRNA. miR-133a was predicted to be able to directly bind to the seeding sequences of the 3′-UTR of YES1.

Dual luciferase assay

Luciferase reporter vectors were constructed by amplifying the 3′-UTR of wild-type or mutant YES1 and subcloning them downstream of the luciferase gene in the pcDNA3.1 luciferase vector (Promega). Then, 50 ng of the above vectors containing firefly luciferase together with 25 ng of miR-133a mimics were transfected into human embryonic kidney 293 cells (ATCC® CRL-3216™). The high transfection efficiency of 293 cells contributes to show clearer changes in luciferase activity to verify the relationship between miR-133a and YES1. 293 cells only with 50 ng of pcDNA3.1 luciferase vector were used as the control (Blank). Subsequently, the luciferase activity was measured through dual luciferase assay system (Promega). All experiments were run in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data were shown as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 or Graphpad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The association between miR-133a and clinicopathological characteristics in NSCLC patients was calculated by χ2 test. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to examine the correlation between the miR-133a and YES1 expression in NSCLC tissues. Differences between groups were calculated by Tukey's one-way ANOVA. Survival curves were detected by Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox analysis. Log-rank test was used to compare survival differences. Significant difference was defined at P<0.05.

Results

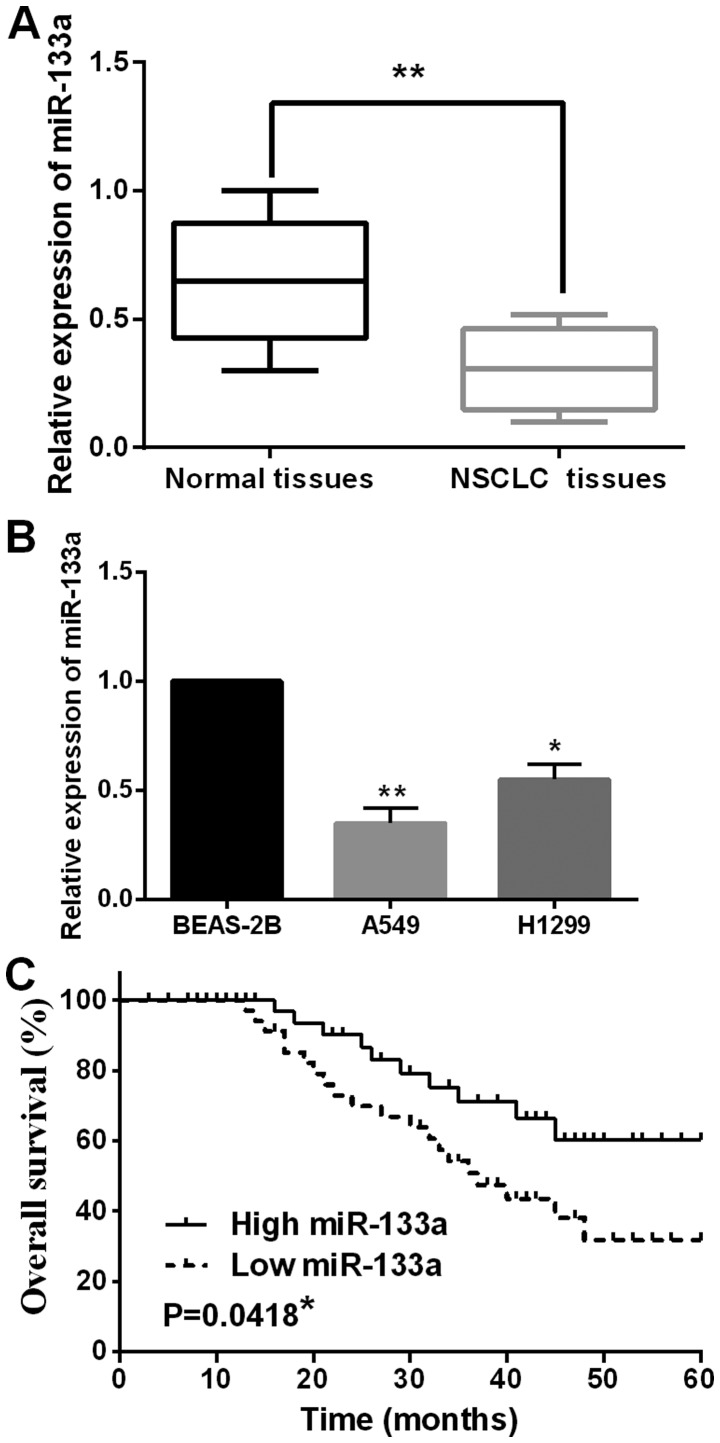

miR-133a is downregulated in NSCLC

First, the expression levels of miR-133a in 52 cases of NSCLC tissues were examined. The median relative expression level of miR-133a in these tissues was taken as a cut-off point to separate low and high expression of miR-133a. We found that the aberrant expression of miR-133a was associated with lymph node metastasis and tumor stage (Table I). Furthermore, the expression of miR-133a was reduced in NSCLC tissues compared to normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Then, miR-133a expression was observed in H1299, A549 and BEAS-2B cell lines. Similarly, downregulation of miR-133a was also detected in H1299 and A549 cell lines compared to BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 1B). In addition, low miR-133a expression was found to have a shorter overall survival rate in NSCLC patients (P=0.0418, Fig. 1C). These results suggest that miR-133a may be involved in tumorigenesis of NSCLC.

Table I.

Association between miR-133a expression and their clinicopathological characteristics in NSCLC patients.

| miR-133a | YES1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Cases | High | Low | P-value | Cases | High | Low | P-value |

| Age (years) | 0.256 | 0.325 | ||||||

| ≥60 | 30 | 12 | 18 | 31 | 22 | 9 | ||

| <60 | 22 | 5 | 17 | 21 | 16 | 5 | ||

| Sex | 0.235 | 0.301 | ||||||

| Male | 32 | 9 | 23 | 33 | 24 | 9 | ||

| Female | 20 | 8 | 12 | 19 | 14 | 5 | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.082 | 0.073 | ||||||

| ≤3 | 35 | 9 | 26 | 36 | 28 | 8 | ||

| >3 | 17 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 10 | 6 | ||

| Lymph nodes metastasis | 0.048a | 0.032a | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 6 | ||

| No | 40 | 12 | 28 | 41 | 33 | 8 | ||

| Tumor stage | 0.045a | 0.033a | ||||||

| I–II | 41 | 11 | 30 | 39 | 31 | 8 | ||

| III–IV | 11 | 6 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 6 | ||

Statistical analyses were performed by the χ2 test.

P<0.05, indicates significant difference. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Downregulation of miR-133a was detected in NSCLC. (A) The expression of miR-133a was detected in NSCLC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. (B) The expression of miR-133a was measured in A549, H1299 and BEAS-2B cell lines. (C) Low miR-133a expression was related to shorter overall survival in NSCLC patients. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

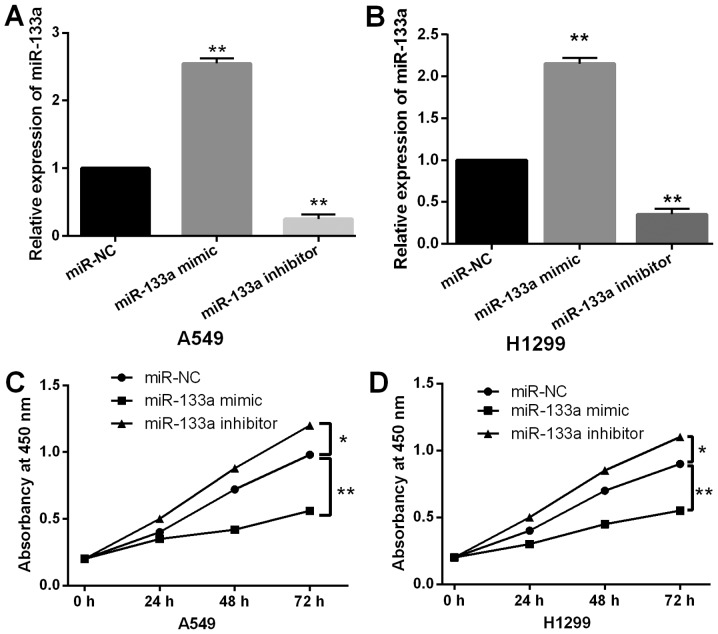

Overexpression of miR-133a inhibits cell proliferation in NSCLC

To explore the role of miR-133a in NSCLC, A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics or inhibitor was prepared to perform gain-loss functional experiment. First, we found that miR-133a expression was increased by miR-133a mimics and decreased by miR-133a inhibitor in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 2A and B). Next, the overexpression of miR-133a was found to inhibit cell proliferation in A549 cells. Additionally, downregulation of miR-133a promoted A549 cell proliferation (Fig. 2C). Consistently, the same effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation was also identified in H1299 cells (Fig. 2D). These findings revealed that miR-133a regulated tumorigenesis of NSCLC by restraining cell proliferation.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of miR-133a inhibits cell proliferation in NSCLC. (A and B) Expression of miR-133a was examined in A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics or inhibitor. (C and D) Cell proliferation was measured in A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics or inhibitor. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

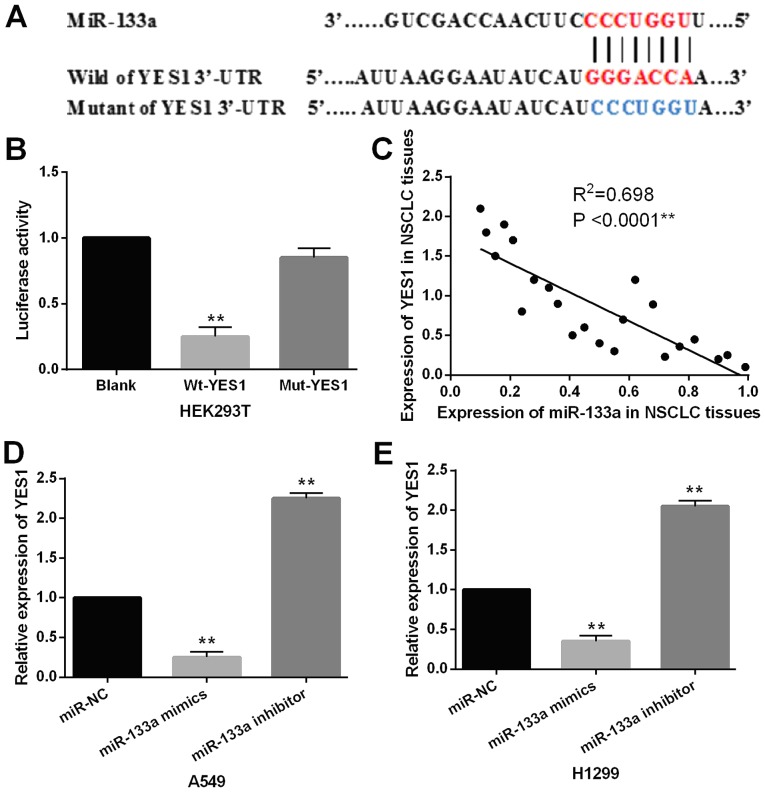

YES1 is a direct target gene of miR-133a

YES1 was selected as a target gene of miR-133a. TargetScan database (http://www.targetscan.org/) shows that miR-133a has a binding site with the 3′-UTR of YES1 (Fig. 3A). Luciferase reporter was preformed to confirm this prediction in 293 cells. We found that miR-133a mimics significantly reduced the luciferase activity of Wt-YES1. However, the luciferase activity of Mut-YES1 was not affected by miR-133a mimics (Fig. 3B). Then, a negative correlation between YES1 and miR-133a was identified in NSCLC tissues (P<0.0001, R2=0.698; Fig. 3C). Next, the expression level of YES1 was examined in A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics or inhibitor. The results showed that miR-133a mimics reduced YES1 expression, while miR-133a inhibitor enhanced YES1 expression in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 3D and E). Thus, YES1 was confirmed as a direct target of miR-133a and inversely regulated miR-133a expression in NSCLC.

Figure 3.

YES1 is a direct target of miR-133a. (A) miR-133a has binding sites with the 3′-UTR of YES1. (B) Luciferase reporter assay. 293 cells only with 50 ng of pcDNA3.1 luciferase vector were used as the control (Blank) (C) miR-133a was inversely correlated with YES1 expression in NSCLC tissues. (D and E) The expression of YES1 was observed in A549 and H1299 cells with miR-133a mimics or inhibitor. **P<0.01. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

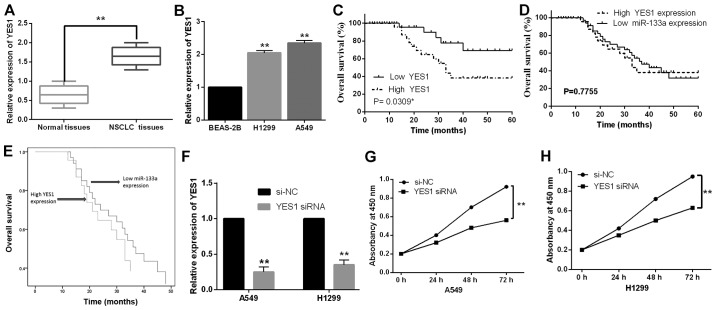

Downregulation of YES1 inhibits proliferation of NSCLC cells

Next, the expression levels of YES1 were detected in 52 cases of NSCLC tissues. The median relative expression level of YES1 in these tissues was taken as a cut-off point to distinguish the low or high YES1 expression. The abnormal expression of YES1 was found to be correlated with lymph node metastasis and tumor stage (Table I). In addition, the expression of YES1 was increased in NSCLC tissues compared to normal tissues (Fig. 4A). Similarly, upregulation of YES1 was also observed in H1299 and A549 cell lines compared to BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, in NSCLC patients high YES1 expression was found to predict poor prognosis (P=0.0309, Fig. 4C). Next, the unfavorable patterns (low miR-133a expression and high YES expression) were combined in the Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox analysis. We found that there was no significant difference in overall survival rate between low miR-133a expression and high YES1 expression (P>0.05, Fig. 4D and E). To explore the effect of YES1 on cell proliferation in NSCLC, YES1 siRNA was transfected into H1299 and A549 cells. RT-qPCR showed that the expression of YES1 was significantly reduced by YES1 siRNA in A549 and H1299 cells compared with the control (Fig. 4F). Functionally, knockdown of YES1 was found to inhibit cell proliferation in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 4G and H). These results suggested that YES1 promoted cell proliferation and predicted prognosis in NSCLC.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of YES1 inhibits cell proliferation in NSCLC. (A) Expression of YES1 was measured in NSCLC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. (B) The expression of YES1 was observed in H1299, A549 and BEAS-2B cell lines. (C) High YES1 expression was related to shorter overall survival in NSCLC patients. (D and E) Combination of unfavorable pattern (low miR-133a expression and high YES1 expression) was evaluated in NSCLC patients using Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox analysis. (F) Expression of YES1 was observed in A549 and H1299 cells with YES1 siRNA or si-NC. (G and H) The cell proliferation was measured in A549 and H1299 cells with YES1 siRNA or si-NC. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Upregulation of YES1 abolishes the inhibitory effect of miR-133a in NSCLC

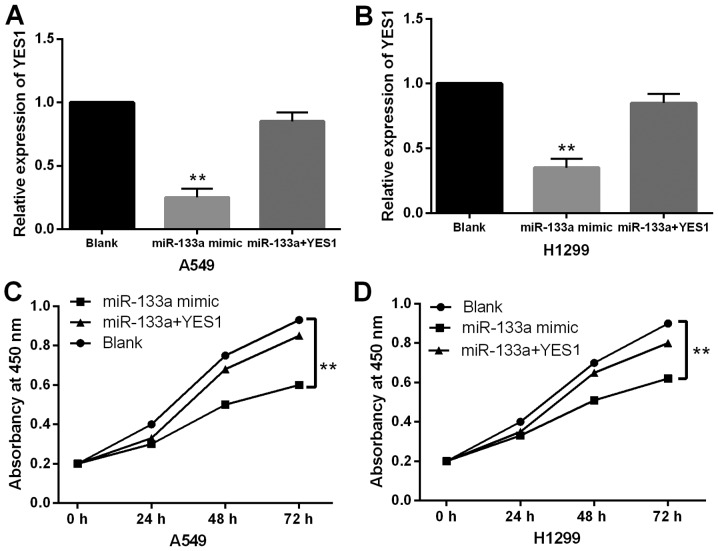

To verify the interaction between miR-133a and YES1 in NSCLC, YES1 overexpression vector was transfected into A549 and H1299 cells containing miR-133a mimics. First, it was found that miR-133a mimics-induced decrease in YES1 expression was restored by YES1 overexpression vector in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 5A and 5B). Functionally, the inhibitory effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation was weakened by the upregulation of YES1 in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 5C and D). Collectively, upregulation of YES1 abolished the inhibitory effect of miR-133a in NSCLC.

Figure 5.

Upregulation of YES1 abolishes the inhibitory effect of miR-133a in NSCLC. (A and B) Expression of YES1 was measured in A549 and H1299 cells with YES1 overexpression vector and miR-133a mimics. (C and D) Cell proliferation was measured in A549 and H1299 cells with YES1 overexpression vector and miR-133a mimics. Untreated cells were used as the controls (Blank). **P<0.01. miR-133a, microRNA-133a; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Discussion

An increasing number of miRNAs has been proposed to be involved in the pathogenesis of human cancer, including NSCLC (17,18). Among them, the downregulation of miR-133a was identified in several human cancers, including breast cancer (19) and colorectal cancer (20). In this study, miR-133a was also downregulated in NSCLC. Furthermore, this downregulation was found to be correlated with adverse lymph node metastasis and tumor stage in NSCLC patients, which has not been reported in previous studies. We also found that low miR-133a expression was closely correlated with shorter overall survival in NSCLC patients. Consistent with our results, miR-133a was also reported to predict poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (21). In addition, the overexpression of miR-133a was identified to restrain NSCLC cell proliferation in our study. Previous studies have demonstrated the inhibitory effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation in gastric cancer (22) and laryngeal carcinoma (23). These findings indicate that miR-133a may promote the tumor growth of NSCLC. However, the correlation between miR-133a expression and tumor size in NSCLC patients were not found in the present study. We speculate that this difference may be due to the small number of samples we collected. The number of samples will be expanded to further confirm our results.

In addition, it is well-known that miRNAs exhibit their effect through regulating expression of target genes (24). Moreover, miR-133a was also identified to regulate tumorigenesis by mediating target genes, such as SENP1 (25) and USP39 (26). To further explain the regulatory mechanism of miR-133a in NSCLC, we also investigated its downstream target in this study. Here, YES1 was confirmed as direct target gene of miR-133a, which has not been found in previous studies. Furthermore, we found that miR-133a restrained proliferation of NSCLC cells by downregulating YES1.

The role of YES1 was also explored in the current study. Upregulation of YES1 was detected in NSCLC, which was correlated with worse clinical outcomes and prognosis in NSCLC patients. Moreover, knockdown of YES1 was found to suppress NSCLC cell proliferation. Similar to our results, it has been reported that YES1 promoted lung cancer growth and progression (27). In the present study, upregulation of YES1 was found to abolish the inhibitory effect of miR-133a on cell proliferation in NSCLC. Similar interaction between YES1 and other miRNAs was also reported in previous studies, such as miR-140-5p (28). All these findings suggest that miR-133a serves as an inhibitor for NSCLC development by suppressing YES1 expression. However, the role of miR-133a in vivo and the effect of miR-133a on NSCLC cell metastasis have not yet been investigated.

In conclusion, downregulation of miR-133a was detected in NSCLC and was correlated with poor clinical outcomes and prognosis in NSCLC patients. Importantly, miR-133a inhibited proliferation of NSCLC cells via targeting YES1. Our findings show potential to provide a new approach to the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YS contributed to the study design, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. FC was involved in data acquisition and revision of the manuscript. YL contributed to the study design, data analysis, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Zhuzhou Hospital of Xiangya Medical College CSU (Zhuzhou, China). Signed informed consents were obtained from the patients or their guardians.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ramalingam SS, Owonikoko TK, Khuri FR. Lung cancer: New biological insights and recent therapeutic advances. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:91–112. doi: 10.3322/caac.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma A, O'Connor R, Celestino P, Killion S, Griswold-Krupski L, Bansal-Travers M. Focus groups and in-depth interviews to guide the development of lung cancer screening informational materials. J Cancer Educ. 2018 Apr 20; doi: 10.1007/s13187-018-1362-4. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1007/s13187-018-1362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Z, Li J, Shen Q, Feng J, Liu H, Wang W, Xu L, Shi G, Ye X, Ge M, et al. Contribution of upregulated dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) in promoting tumorigenicity, metastasis and the prediction of poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1620–1632. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F, Wei K, Qin Z, Liu W, Shao C, Wang C, Ma L, Xie M, Shu Y, Shen H. miR-598 suppresses invasion and migration by negative regulation of Derlin-1 and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;47:245–256. doi: 10.1159/000489803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang JZ, Bian L, Hou JG, Wang HY. miR-550a-3p promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and metastasis through down-regulating TIMP2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4156–4165. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201807_15408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y, Wu Y, Dong J, Han D, Yang S, Jiang L. MicroRNA-133a-3p exerts inhibitory effects on gallbladder carcinoma via targeting RBPJ. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:2448–2462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao SH, Liu J, Zhang HJ, Zhao N, Zhang J. Low miR-133a expression is a predictor of outcome in patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:3788–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Li J, Chen H, Mo Y, Ye H, Luo Y, Guo K, Mai Z, Zhang Y, Chen B, et al. Down-regulation of miR-133a as a poor prognosticator in non-small cell lung cancer. Gene. 2016;591:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai J, Liu T, Huang P, Yan W, Guo C, Xiong L, Liu A. USP39, a direct target of microRNA-133a, promotes progression of pancreatic cancer via the AKT pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeung CL, Ngo VN, Grohar PJ, Arnaldez FI, Asante A, Wan X, Khan J, Hewitt SM, Khanna C, Staudt LM, et al. Loss-of-function screen in rhabdomyosarcoma identifies CRKL-YES as a critical signal for tumor growth. Oncogene. 2013;32:5429–5438. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Je DW, O YM, Ji YG, Cho Y, Lee DH. The inhibition of SRC family kinase suppresses pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Pancreas. 2014;43:768–776. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato A, Sekine M, Virgona N, Ota M, Yano T. Yes is a central mediator of cell growth in malignant mesothelioma cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1889–1893. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida M, Brand TM, Campbell DA, Li C, Wheeler DL. Yes and Lyn play a role in nuclear translocation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncogene. 2013;32:759–767. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seki T, Fujii G, Mori S, Tamaoki N, Shibuya M. Amplification of c-yes-1 proto-oncogene in a primary human gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1985;76:907–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Sun L, Li J, Jiang R. miR-577 suppresses cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating the WNT2B mediated Wnt/β-catenin pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:2753–2761. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han L, Chen W, Xia Y, Song Y, Zhao Z, Cheng H, Jiang T. miR-101 inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer by targeting zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10:1172–1183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sui Y, Zhang X, Yang H, Wei W, Wang M. MicroRNA-133a acts as a tumour suppressor in breast cancer through targeting LASP1. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:473–482. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Li W, Chen A, Xiong L, Chen T, Tao F, Lu Y, He Q, Zhao L, Ou R, Xu Y. miR-133a acts as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer by targeting eIF4A1. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317698389. doi: 10.1177/1010428317698389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun L, Guo Z, Sun J, Li J, Dong Z, Chen J, Kan Q, Yu Z. miR-133a acts as an anti-oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting FOSL2 through TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;107:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Li X, Gao S, Li C, Ma L. MicroRNA-133a inhibits proliferation of gastric cancer cells by downregulating ERBB2 expression. Oncol Res. 2017;25:1169–1176. doi: 10.3727/096504017X14847395834985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Wang Y, Li YZ. MicroRNA-133a suppresses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of laryngeal carcinoma cells by targeting CD47. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:16103–16113. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5451-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farazi TA, Juranek SA, Tuschl T. The growing catalog of small RNAs and their association with distinct Argonaute/Piwi family members. Development. 2008;135:1201–1214. doi: 10.1242/dev.005629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou GQ, Han F, Shi ZL, Yu L, Li XF, Yu C, Shen CL, Wan DW, Zhu XG, Li R, et al. miR-133a-3p targets SUMO-specific protease 1 to inhibit cell proliferation and cell cycle progress in colorectal cancer. Oncol Res. 2018;26:795–800. doi: 10.3727/096504017X15004613574679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong X, Su H, Jiang F, Li H, Shi G, Fan L. miR-133a, directly targeted USP39, suppresses cell proliferation and predicts prognosis of gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:8311–8318. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garmendia I, Pajares MJ, Hermida-Prado F, Ajona D, Bértolo C, Sainz C, Lavín A, Remírez AB, Valencia K, Moreno H, et al. YES1 drives lung cancer growth and progression and predicts sensitivity to dasatinib. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Jun 5; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1292OC. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1292OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang Z, Yin S, Sun R, Zhang S, Fu M, Wu Y, Zhang T, Khaliq J, Li Y. miR-140-5p suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer by regulating YES1. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:139. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0708-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.