Abstract

Background

Multiple myeloma is a bone marrow‐based hematological malignancy accounting for approximately two per cent of cancers. First‐line treatment for transplant‐ineligible individuals consists of multiple drug combinations of bortezomib (V), lenalidomide (R), or thalidomide (T). However, access to these medicines is restricted in many countries worldwide.

Objectives

To assess and compare the effectiveness and safety of multiple drug combinations of V, R, and T for adults with newly diagnosed transplant‐ineligible multiple myeloma and to inform an application for the inclusion of these medicines into the World Health Organization's (WHO) list of essential medicines.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL and MEDLINE, conference proceedings and study registries on 14 February 2019 for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing multiple drug combinations of V, R and T for adults with newly diagnosed transplant‐ineligible multiple myeloma.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing combination therapies of V, R, and T, plus melphalan and prednisone (MP) or dexamethasone (D) for first‐line treatment of adults with transplant‐ineligible multiple myeloma. We excluded trials including adults with relapsed or refractory disease, trials comparing drug therapies to other types of therapy and trials including second‐generation novel agents.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias of included trials. As effect measures we used hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) and risk ratios (RRs) for adverse events. An HR or RR < 1 indicates an advantage for the intervention compared to the main comparator MP. Where available, we extracted quality of life (QoL) data (scores of standardised questionnaires). Results quoted are from network meta‐analysis (NMA) unless stated.

Main results

We included 25 studies (148 references) comprising 11,403 participants and 21 treatment regimens. Treatments were differentiated between restricted treatment duration (treatment with a pre‐specified amount of cycles) and continuous therapy (treatment administered until disease progression, the person becomes intolerant to the drug, or treatment given for a prolonged period). Continuous therapies are indicated with a "c". Risk of bias was generally high across studies due to the open‐label study design.

Overall survival (OS)

Evidence suggests that treatment with RD (HR 0.63 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.99), median OS 55.2 months (35.2 to 87.0)); TMP (HR 0.75 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.97), median OS: 46.4 months (35.9 to 60.0)); and VRDc (HR 0.49 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.92), median OS 71.0 months (37.8 to 133.8)) probably increases survival compared to median reported OS of 34.8 months with MP (moderate certainty). Treatment with VMP may result in a large increase in OS, compared to MP (HR 0.70 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.07), median OS 49.7 months (32.5 to 77.3)), low certainty).

Progression‐free survival (PFS)

Treatment withRD (HR 0.65 (95% CI0.44 to 0.96), median PFS: 24.9 months (16.9 to 36.8)); TMP (HR 0.63 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.78), median PFS:25.7 months (20.8 to 32.4)); VMP (HR 0.56 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.90), median PFS: 28.9 months (18.0 to 46.3)); and VRDc (HR 0.34 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.58), median PFS: 47.6 months (27.9 to 81.0)) may result in a large increase in PFS (low certainty) compared to MP (median reported PFS: 16.2 months).

Adverse events

The risk of polyneuropathies may be lower with RD compared to treatment with MP (RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.16 to 1.99), risk for RD: 0.5% (0.1 to 1.8), mean reported risk for MP: 0.9% (10 of 1074 patients affected), low certainty). However, the CIs are also compatible with no difference or an increase in neuropathies. Treatment with TMP (RR 4.44 (95% CI1.77 to 11.11), risk: 4.0% (1.6 to 10.0)) and VMP (RR 88.22 (95% CI 5.36 to 1451.11), risk: 79.4% (4.8 to 1306.0)) probably results in a large increase in polyneuropathies compared to MP (moderate certainty). No study reported the amount of participants with grade ≥ 3 polyneuropathies for treatment with VRDc.

VMP probably increases the proportion of participants with serious adverse events (SAEs) compared to MP (RR 1.28 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.54), risk for VMP: 46.2% (38.3 to 55.6), mean risk for MP: 36.1% (177 of 490 patients affected), moderate certainty). RD, TMP, and VRDc were not connected to MP in the network and the risk of SAEs could not be compared.

Treatment with RD (RR 4.18 (95% CI 2.13 to 8.20), NMA‐risk: 38.5% (19.6 to 75.4)); and TMP (RR 4.10 (95% CI 2.40 to 7.01), risk: 37.7% (22.1 to 64.5)) results in a large increase of withdrawals from the trial due to adverse events (high certainty) compared to MP (mean reported risk: 9.2% (77 of 837 patients withdrew)). The risk is probably slightly increased with VMP (RR 1.06 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.81), risk: 9.75% (5.8 to 16.7), moderate certainty), while it is much increased with VRDc (RR 8.92 (95% CI 3.82 to 20.84), risk: 82.1% (35.1 to 191.7), high certainty) compared to MP.

Quality of life

QoL was reported in four studies for seven different treatment regimens (MP, MPc, RD, RMP, RMPc, TMP, TMPc) and was measured with four different tools. Assessment and reporting differed between studies and could not be meta‐analysed. However, all studies reported an improvement of QoL after initiation of anti‐myeloma treatment for all assessed treatment regimens.

Authors' conclusions

Based on our four pre‐selected comparisons of interest, continuous treatment with VRD had the largest survival benefit compared with MP, while RD and TMP also probably considerably increase survival. However, treatment combinations of V, R, and T also substantially increase the incidence of AEs, and lead to a higher risk of treatment discontinuation. Their effectiveness and safety profiles may best be analysed in further randomised head‐to‐head trials. Further trials should focus on consistent reporting of safety outcomes and should use a standardised instrument to evaluate QoL to ensure comparability of treatment‐combinations.

Plain language summary

Multiple drug combinations of bortezomib, lenalidomide and thalidomide for initial treatment of adults with transplant‐ineligible multiple myeloma

Background

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer. It accounts for approximately 2% of all cancers and is still considered incurable. For people with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), who are unsuitable for a procedure where damaged blood cells are replaced with healthy ones (stem‐cell transplant), treatment is usually a multiple drug combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide, or thalidomide, plus melphalan and prednisolone (MP) or dexamethasone (D). Multiple drug combinations are approved for initial anti‐myeloma therapy, however, access to these medicines is restricted in many countries worldwide.

Aim of the review

To compare the benefits and harms of selected anti‐myeloma drugs (bortezomib (V), lenalidomide (R), thalidomide (T)) for transplant‐unsuitable NDMM.

Study characteristics

We searched selected medical databases and trial registries until 14th February 2019. We included studies comparing multiple drug combinations of V, R, and T for the treatment of people with NDMM who were unsuitable for a stem‐cell transplant. We differentiated between fixed treatment duration and continuous therapy. Fixed therapy is a pre‐specified number of cycles, while a continuous therapy is given until the disease gets worse, the person finds the drug hard to tolerate, or when the treatment is given for a prolonged period. Continuous therapies are indicated with a "c".

Key results

We identified 25 studies involving 11,403 transplant‐unsuitable adults with NDMM, and comparing 21 different treatment regimens.

Survival

People who had the standard treatment, MP, lived for an average of 35 months. People treated with RD, TMP, and VRDc probably live for much longer (moderate certainty). Treatment with VMP may also lead to much longer survival, compared to MP (low certainty). People treated with RD lived for an additional 20.4 months; with TMP an additional 11.6 months; with VRDc an additional 36.2 months, and with VMP an additional 14.9 months.

Harms

On average, 0.9% (9 out of 1000) of people treated with MP experienced peripheral nerve damage (polyneuropathies).The evidence was inconclusive whether treatment with RD decreases the risk of developing a polyneuropathy, compared to MP. The estimated risk of polyneuropathies with RD was 0.5%. Treatment with TMP and VMP probably increases the risk of experiencing polyneuropathies compared to MP (moderate certainty). The estimated risk with TMP was 4.0%, and with VMP 79.4%. No VRDc treatment study reported the number of participants with severe polyneuropathies.

On average, 36.1% (361 out of 1000) of people on MP‐treatment experienced at least one serious adverse event (SAE). VMP probably increases the proportion of participants with SAEs compared to MP to 46.2% (moderate certainty).

On average, 9.2% (92 out of 1000) of people treated with MP stop the treatment because of adverse events (AEs). Treatment with RD, TMP, and VRDc leads to a much higher proportion of people stopping treatment because of AEs than MP (high certainty). The risk of stopping treatment with RD is 38.5%; with TMP 37.7%, with VRDc 82.1%. Treatment with VMP probably increases the risk of stopping treatment because of AEs compared to MP (9.75%, moderate certainty).

Quality of life

Quality of life (QoL) was reported in four studies for seven different treatments and was measured with four different tools. Assessment and reporting differed between studies and could not be meta‐analysed. However, all studies reported an improvement in QoL after anti‐myeloma treatment was started for all assessed treatments.

Conclusions

VRDc showed the highest overall survival benefits, compared to MP. RD and TMP also improved OS compared to MP. However, these combinations of drugs also led to more adverse events compared to MP, and led to more people stopping treatment. More trials are needed that look carefully at both harms and QoL.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Multiple drug combinations of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and thalidomide for first‐line treatment in transplant‐ineligible multiple myeloma patients | |||||

|

Patient or population: newly diagnosed, transplant‐ineligible adults with symptomatic multiple myeloma Settings: mostly outpatient; mostly multi‐centre studies across Europe, Asia, North‐ and South America, Australia, and the Pacific region Intervention: lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (RD), thalidomide plus melphalan and prednisone (TMP), bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone (VMP), continuous bortezomib plus lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (VRDc) Comparison: melphalan and prednisone (MP) | |||||

| Outcomes | Effects and 95% confidence intervals in the effects. Main comparator is MP* | ||||

| Risk with MP | Risk with RD | Risk with TMP | Risk with VMP | Risk with VRDc | |

| Overall survival | Median overall survival over all studies in the network1: 34.8 months | NMA‐median OS: 55.2 (35.2 to 87.0) months | NMA‐median OS: 46.4 (35.9 to 60.0) months | NMA‐median OS: 49.7 (32.5 to 77.3) months | NMA‐median OS: 71.0 (37.8 to 133.8) months |

| NMA‐HR: 0.63 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.99) | NMA‐HR: 0.75 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.97) | NMA‐HR: 0.70 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.07) | NMA‐HR: 0.49 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.92) | ||

| ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates due to inconsistency of I² = 53.9% (downgrade minus 1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates due to inconsistency of I² = 53.9% (downgrade minus 1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates due to inconsistency of I² = 53.9% (downgrade minus 1), imprecision (downgrade minus 1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates due to inconsistency of I² = 53.9% (downgrade minus 1) | ||

| Progression‐free survival | Median progression‐free survival over all studies included in the network1: 16.2 months | NMA‐median PFS: 24.9 (16.9 to 36.8) months | NMA‐median PFS: 25.7 (20.8 to 32.4) months | NMA‐median PFS: 28.9 (18.0 to 46.3) months | NMA‐median PFS: 47.6 (27.9 to 81.0) months |

| NMA‐HR: 0.65 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.96) | NMA‐HR: 0.63 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.78) | NMA‐HR: 0.56 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.90) | NMA‐HR: 0.34 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.58) | ||

| ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates due to high risk of bias (downgrade minus 1) and inconsistency of I² = 55.3% (downgrade minus 1). | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates due to high risk of bias (downgrade minus 1) and inconsistency of I² = 55.3% (downgrade minus 1). | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates due to high risk of bias (downgrade minus 1) and inconsistency of I²=55.3% (downgrade minus 1). | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates due to high risk of bias (downgrade minus 1) and inconsistency of I² = 55.3% (downgrade minus 1). | ||

| Polyneuropathies | Mean risk over all studies included in the network²: 0.9% (10/1074) | NMA‐risk: 0.5% (0.1 to 1.8) | NMA‐risk: 4.0% (1.6 to 10.0) | NMA‐risk: 79.4% (4.8 to 1306.0) | No study reported the amount of participants with grade ≥ 3 polyneuropathies for treatment with VRDc. |

| NMA‐RR: 0.57 (95% CI 0.16 to 1.99) | NMA‐RR: 4.44 (95% C: 1.77 to 11.11) | NMA‐RR: 88.22 (95% CI 5.36 to 1451.11) | |||

| ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low confidence in estimates. Downgrade minus 1 for imprecision and minus 1 for high risk of bias. | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates. Downgrade minus 1 for high risk of bias. | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates. Downgrade minus 1 for high risk of bias. | |||

| Serious adverse events | Mean risk over all studies included in the network²: 36.1% (177/490) | Risk not available, because RD is not connected to MP in the network. | Risk not available, because TMP is not connected to MP in the network. | NMA‐risk: 46.2% (38.3 to 55.6) | Risk not available, because VRDc is not connected to MP in the network. |

| NMA‐RR not available, because RD is not connected to MP in the network. | NMA‐RR not available, because TMP is not connected to MP in the network. | NMA‐RR: 1.28 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.54) | NMA‐RR not available, because VRDc is not connected to MP in the network. | ||

| Confidence in estimates can not be assessed, because RD is not connected to MP in the network. | Confidence in estimates can not be assessed, because TMP is not connected to MP in the network. | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates. Downgrade minus 1 for high risk of bias. | Confidence in estimates can not be assessed, because VRDc is not connected to MP in the network. | ||

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | Mean risk over all studies included in the network²: 9.2% (77/837) | NMA‐risk: 38.5% (19.6 to 75.4) | NMA‐risk: 37.7% (22.1 to 64.5) | NMA‐risk: 9.75% (5.8 to 16.7) | NMA‐risk: 82.1% (35.1 to 191.7) |

| NMA‐RR: 4.18 (95% CI 2.13 to 8.20) | NMA‐RR: 4.10 (95% CI 2.40 to 7.01) | NMA‐RR: 1.06 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.81) | NMA‐RR: 8.92 (95% CI 3.82 to 20.84) | ||

| ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high confidence in estimates. | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high confidence in estimates. | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate confidence in estimates. Downgrade minus 1 for imprecision. | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high confidence in estimates. | ||

| Quality of life | One study reported that health‐related QoL scores increased steadily from baseline until completion of cycle 10 | One study reported that global health status of patients improved from baseline over the duration of the study and disease symptoms decreased | One study reported that global health status of patients improved from baseline over the duration of the study and disease symptoms decreased | No study reported the outcome QoL for treatment with VMP. | No study reported the outcome QoL for treatment with VRDc. |

| RD was not compared to MP in this study | TMP was not compared to MP in this study | ||||

| *Basis for the assumed risks: 1: Median OS/PFS over all studies in the network were estimated, calculating the mean of all available MP‐medians (OS and PFS, respectively). 2: mean risk over all studies included in the network was estimated, dividing the total events under MP‐therapy by the total of patients treated with MP. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; MP: Melphalan and Prednisone; RD: Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone; TMP: Thalidomide, Melphalan and Prednisone; VMP: Bortezomib, Melphalan and Prednisone; VRDc: continuous Bortezomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

Background

Description of the condition

Multiple myeloma, also known as plasma cell myeloma, is a bone marrow‐based hematological malignancy. Myeloma arises from asymptomatic premalignant monoclonal plasma cells via a multistep process of genetic and microenvironmental changes (Palumbo 2011). In contrast to other hematological malignancies, multiple myeloma is usually preceded by an age‐progressive benign condition called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), which further progresses to smouldering (asymptomatic) myeloma and finally to symptomatic myeloma (Anderson 2011; Kuehl 2012).

Early diagnosis of the condition is complicated by widely varying symptoms. Some patients might be symptom‐free, while others present with common symptoms like fatigue, bone pain (mostly in the back, or hips), bone fractures, symptoms of light chain amyloidosis, or high calcium levels in the blood. Amongst others, the latter might lead to kidney problems, abdominal pain, or extreme thirst (The American Cancer Society 2018). The criteria for myeloma diagnosis have been revised in 2014 by the International Myeloma Working Group. These criteria are: presence of at least 10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow or biopsy‐proven or extramedullary plasmacytoma and one (or more) myeloma‐defining events (Table 2) (Rajkumar 2014).

1. Myeloma defining events.

| Myeloma defining events (Rajkumar 2014) | |

| CRAB criteria | |

| Hypercalcaemia | > 2.75 mmol/L (> 11 mg/dL) |

| Renal insufficiency | creatine clearance < 40 mL per min or serum creatine > 177 µmol/L (> 2 mg/dL) |

| Anaemia | haemoglobin value < 100 g/L |

| Bone lesions | 1 or more oseolytic lesions on skeletal radiography, computer tomography, or positron emission tomography‐computer tomography |

| Biomarkers of malignancy (SLiM criteria) | |

| clonal bone marrow plasma cell %‐age | ≧ 60 (Sixty)% |

| Involved to uninvolved serum free Light chain ratio | ≧ 100 |

| focal lesions on Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies | < 1 |

To date, multiple myeloma is still considered incurable and accounts for approximately ten per cent of all hematological malignancies and two per cent of all cancers (Cancer Research UK 2018). Globally, there were 138,509 incident cases in 2016 (Cowan 2018). The incident rate increased worldwide by 126% between 1990 and 2016 and is strongly related to age (Cancer Research UK 2018; Cowan 2018). Based on the latest statistics in the USA, the median age of myeloma diagnosis across all races and both genders is 69 years of age (National Cancer Institute 2018). The prognosis of five‐year survival differs widely between high‐income countries and low‐ and middle‐income countries. In the UK, 47% of people diagnosed with multiple myeloma are predicted to survive for at least five years (32.5% for at least 10 years). The reported five‐year survival for men is 49.8%, and for women 43.8% (Cancer Research UK 2018). Later diagnosis and limited access to specialised health care reduces the survival period. In comparison, a recent study in Nigeria reported a five‐year survival rate of only 7.6% (Nwabuko 2017).

Description of the intervention

First‐line treatment for people with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

The recommended first‐line standard treatment for people with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) in good clinical condition consists of induction chemotherapy followed by high‐dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (Moreau 2017). Some individuals with myeloma might be unsuitable for transplantation because of co‐morbidities, frailty, or limited financial resources (Anderson 2015; Cowan 2018). The combination of melphalan and prednisone (MP) was the former standard treatment for individuals unsuitable for transplantation. This was modified after the introduction of so‐called "novel agents" in the late 1990s to early 2000s. Since then, the preferred first‐line therapy regimens for transplant‐ineligible individuals, consists of two‐, three‐ or multiple‐drug combinations of novel agents. These agents belong to different drug classes including: proteasome inhibitors, e.g. bortezomib; immunomodulatory drugs, e.g. lenalidomide and thalidomide; and corticosteroids, e.g. dexamethasone and prednisone (Anderson 2015; Kumar 2018; Moreau 2017).

The introduction of immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors in the treatment of transplant‐ineligible individuals with NDMM has shown a major improvement in overall and progression‐free survival (OS and PFS, respectively). Adding thalidomide (T) and lenalidomide (R) to the melphalan and prednisone (MP) standard regimen led to an increase of OS (40 months versus 31 months, respectively) (Wijermans 2010), and PFS in 65 to 75 year old adults (median PFS with RMP: (lenalidomide,melphalan and prednisone) 15 months versus median PFS with MP: 12 months) (Palumbo 2012), respectively. Extending the standard regimen with bortezomib (V) likewise increased OS (median OS with MP alone: 43.1 months versus 56.4 months with added bortezomib), resulting in a 31% death‐risk reduction following VMP versus MP (San Miguel 2013). Furthermore, various two‐ and three‐drug combinations of bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and cyclophosphamide are recommended options for the treatment of transplant‐ineligible individuals with NDMM after showing highly satisfying results in OS and PFS (Anderson 2015; Moreau 2017). Selecting the best first‐line myeloma treatment when faced with multiple effective drug regimens is challenging. Evidence‐based, as well as consensus‐based clinical practice guidelines recommend multiple treatment combinations, without stating a clear ranking of the options (Kumar 2018; Moreau 2017).

Fixed and continuous treatments

Nowadays anti‐myeloma therapies are either administered as fixed or continuous therapies. Fixed therapy usually refers to a treatment with a fixed or pre‐specified number of cycles. Continuous therapies in transplant‐ineligible myeloma refers to: a therapy which is administered until progressive disease or emerging intolerances, a therapy where the treatment is given for a prolonged period but is still limited (e.g. until a plateau in response), or a therapy where an initial therapy is followed by maintenance treatment (Ludwig 2017b). The aim of continuous therapies is to prolong PFS and OS through improving the depth of the response and suppression of minimal residual disease (Richardson 2018). In the early days, anti‐myeloma therapies were administered for a fixed duration of cycles, because long‐term therapy with conventional chemotherapy agents led to an accumulating, indefensible toxicity. Introducing immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors allowed the exploration of continuous therapies, as toxicities of these agents are less severe (Ludwig 2017b). However, although these agents are less toxic, accumulating toxicities of these drug classes are expected to be important. We therefore wanted to focus on drug‐specific adverse events (polyneuropathy, neutropenia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, thromboembolism, and infections) in this review.

Immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors can reduce bone marrow activity (myelosuppression), which may lead to a decrease in red blood cells (anaemia), white blood cells (neutropenia), and platelets (thrombocytopenia) (Miceli 2008). Myelosuppression, especially severe neutropenia can substantially increase the risk of infections. Thalidomide decreases the neutrophil count during the treatment period (days one to 11), whereas lenalidomide decreases the platelet count. During the rest period (days 12 to 21), blood counts return to baseline. During bortezomib treatment thrombocytopenia is the most common haematological toxicity, occurring in around one third of patients, whereas significant neutropenia and anaemia are uncommon.

Bortezomib‐induced peripheral neuropathy usually occurs within the first five courses of bortezomib administration and shows a significant dose‐limiting toxicity of approximately 30 mg/m². Thereafter, typically it does not appear to increase (Argyriou 2008; Windebank 2008).

Generally, the risk for venous thromboembolism is increased in adults with myeloma. Single agent thalidomide or lenalidomide treatment does not increase this risk further. Hovewer, combining immunomodulatory drugs with steroids substantially increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (Palumbo 2008). Most events occur during the first six months of treatment (Kimpton 2016).

In this context, we decided to divide treatment regimens between fixed and continuous therapies to not only compare the effectiveness of treatment regimens, but also of different treatment durations, and to assess whether toxicity of continuous therapies is tolerable.

How the intervention might work

Proteasome‐inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs belong to a new generation of anti‐cancer agents that work by targeting the microenvironment of the tumour, including specific cell receptors, proteins and signalling pathways (Bianchi 2015).

Approved proteasome inhibitors for myeloma treatment include the first‐in‐class agent bortezomib, and the second‐generation agents carfilzomib, and ixazomib. The mode of action in the treatment of multiple myeloma is generally similar for all proteasome inhibitors. It is based on the supreme sensitivity of myeloma cells to the inhibition of the 26S proteasome. This is a critical complex of the ubiquitin‐proteasome system and responsible for regulation and degradation of the majority of intracellular proteins. These proteins are involved in cell cycle progression, cell growth, and survival. In multiple myeloma, the ubiquitin‐proteasome system is dysregulated, resulting in increased activity of proteasome 26S. This leads to a reduction in the levels of important proteins, like the tumour suppressor p53 and the inhibitor of the anti‐apoptotic protein nuclear factor‐κB, IκB. The continuous activity of the nuclear factor‐κB transcription pathway enables myeloma cells to proliferate rapidly and drive tumour progression. Inhibition of the 26S proteasome leads to multiple downstream effects, resulting in growth arrest and cell death. As cancer cells have an increased level of proteasome activity in general, the pro‐apoptotic effects of proteasome inhibitors can therefore be directly targeted (Gandolfi 2017; Moreau 2012).

Immunomodulatory drugs are glutamic acid derivatives presenting a wide range of biological activities. Their anti‐myeloma properties consist of their immunomodulatory, anti‐angiogenic, anti‐inflammatory, and anti‐proliferative properties, though their exact mechanism of action remains unclear. The molecular target of immunomodulatory drugs is Cereblon (reviewed in Asatsuma‐Okumura 2019) and their binding to Cereblon leads to reduction of Ikaros zinc finger family proteins (IKZF) 1 and 3 by ubiquintination and degradation. IKFZ1 and 3 are critical for myeloma cell survival and downregulation of IKFZ1 and 3 suppressed myeloma cell lines in vitro (Fink 2015; Lu 2014). Three immunomodulatory drugs are clinically used for the treatment of multiple myeloma: thalidomide and its analogues, lenalidomide and pomalidomide (the latter only used in relapsed or refractory myeloma) (Quach 2010). Despite their similar structure, thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide differ in their pharmacological properties (Holstein 2017). The immunomodulatory activities are based on the upregulation of T‐cell (CD4+ and CD8+) and natural killer T‐cell production and downregulation of regulatory T‐cells, leading to an increased proliferation of natural killer cells and raised cytotoxicity (Bianchi 2015; Quach 2010). The T‐cell proliferative effects of lenalidomide are 50 to 2000 times higher than that of thalidomide and the effectiveness of T‐cell IL‐2 and IFNγ production augmentation is 300 to more than 1200 times higher (Quach 2010). Likewise, lenalidomide is more effective in decreasing the production of TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, and IL‐12 than thalidomide (Holstein 2017). Increasing natural killer cell proliferation results in enhanced death of myeloma cell lines. In addition to the potentiation of natural killer cell proliferation, lenalidomide (not thalidomide) enhances antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity and natural cytotoxicity of natural killer cells, resulting in induced myeloma cell death (Quach 2010). The cytotoxic capacities of lenalidomide originate from multiple mechanisms, comprising inter alia the inhibition of nuclear factor‐κB, downregulation of C/EBPβ (resulting in a decrease of interferon regulatory factor 4 production), activation of caspases, augmented expression of pro‐apoptotic factors and likewise, deduction of anti‐apoptotic factors, and the interruption of the PI3K/Akt pathway (Holstein 2017).

Combination therapies of proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs and corticosteroids result in synergistic or enhanced activity of the anti‐cancer agents on anti‐myeloma properties (Gandolfi 2017). Corticosteroids probably enhance anti‐cancer activity through the downregulation of IL‐6‐induced signalling pathways. Synergistic effects of proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs are probably due to the combined effects of overlapping activation of caspase pathways, the activation of the proapoptotic BH‐3 protein BIM, the downregulation of interferon regulatory factor 4, the proto‐oncogene MYC, and the apoptosis regulator MCL1 in myeloma cells, and the inhibition of myeloma cell migration and angiogenesis (Gandolfi 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

Double‐ and triple‐drug combinations of novel agents, such as bortezomib, lenalidomide, and thalidomide, are commonly used in high‐income countries for first‐line treatment of adults with multiple myeloma who are unsuitable for transplantation. However, high prices of these anti‐myeloma medicines are limiting their availability in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 150 countries worldwide use the WHO's list of essential medicines (EML) as a guidance for the development of national EMLs and reimbursement lists (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics 2015; World Health Organization 2019). However, currently anti‐myeloma medicines are not in the EML. We therefore decided to prepare an application for the '22nd WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines' for the inclusion of anti‐myeloma medicines into the EML. In several discussions with the respective WHO working group, we decided to focus on bortezomib, lenalidomide, and thalidomide, which belong to the first generation of proteasome‐inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs and are all approved for first‐line treatment. In HICs, a second‐generation of novel agents (e.g. the monoclonal antibody daratumumab) have already been introduced into treatments, however, they are much more expensive. We have therefore concentrated on bortezomib, lenalidomide and thalidomide only, as they more likely to be affordable and available in LMICs.

As there are few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that perform direct head‐to‐head comparisons of different drug combinations, a systematic review and network meta‐analysis was needed to evaluate the cumulative clinical evidence for the effectiveness and safety of these combinations and to create a clinically meaningful ranking of the treatments. The aim of our systematic review and network meta‐analysis was to provide a comprehensive overview on the effectiveness and harms of novel agents for non‐transplant first‐line multiple myeloma treatment. The network meta‐analysis allowed a hierarchy of the therapeutic options, in particular, if the benefits of one option compared to another translated into a clinically important difference. This comprehensive overview was necessary for clinical decision making, and has the potential to affect international guidelines, clinical pathways, and decision support systems for treatment strategies.

The results of this network meta‐analysis will be published in the Cochrane Library and presented at national and international expert meetings and conferences (e.g. European Hematology Association). The results of the network meta‐analysis have the potential to influence the design of new RCTs on novel agents for myeloma treatment. As patient‐related outcomes were evaluated, a direct impact on patient care and treatment is expected.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of different combinations of one or more novel agents (bortezomib, lenalidomide, thalidomide) as treatment of adults with transplant‐ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) to generate a clinically meaningful treatment ranking according to their efficacy and safety and to inform an application for the inclusion of these medicines into the WHO's list of essential medicines.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (Piechotta 2018). We included studies if they were individually randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We included both full‐text and abstract publications if sufficient information on study design, characteristics of participants and interventions provided. There was no limitation with respect to the length of follow‐up.

We excluded studies that were cluster‐randomised, non‐randomised, case reports and clinical observations.

Types of participants

We included trials involving adults according to the definition in the studies (usually ≧ 18 years of age), with a newly confirmed diagnosis of multiple myeloma, irrespective of type and stage of cancer and gender. We assumed that participants who fulfil the inclusion criteria were equally eligible to be randomised to any of the interventions we planned to compare.

We excluded trials including adults with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.

Types of interventions

We included trials that included participants receiving a combination therapy of selected immunomodulatory drugs and/or proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib (V)*, lenalidomide (R)**, thalidomide (T)) in combination with a glucocorticoid (dexamethasone (D), or prednisone (P)) or a glucocorticoid and alkylating agent (cyclophosphamide (C)), or melphalan (M)) in at least one treatment arm for first‐line treatment of transplant‐ineligible myeloma patients.

* V stands for 'Velcade®', the proprietary name of bortezomib.

** R stands for 'Revlimid®', the proprietary name of lenalidomide.

Nowadays, the recommended treatment for adults with transplant‐ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) is either a double‐ or a triple‐drug combination therapy (Kumar 2018; Moreau 2017), consisting of:

immunomodulatory drug (R or T) in combination with a glucocorticoid (D, P) or glucocorticoid and alkylating agent (CD, CP or MP)

proteasome inhibitor (V) in combination with a glucocorticoid (D, P) or glucocorticoid and alkylating agent (CD, CP or MP)

immunomodulatory drug (R or T) in combination with proteasome inhibitor (V), and a glucocorticoid (D, P) or glucocorticoid and alkylating agent (CD, CP or MP)

Regimens, which include either an immunomodulatory drug or a proteasome inhibitor will be referred to as double‐drug combinations. We will refer to triple‐drug combinations, when a immunomodulatory drug and a proteasome inhibitor is included in the regimen.

Combinations of these interventions at any dose and by any route were compared to each other in a full network. We included trials with any treatment duration and divided treatment regimens between fixed and continuous therapies (Description of the intervention).To increase the amount of potential comparisons and to strengthen the network, we also included studies comparing the described double‐ or triple‐drug combinations to the former standard treatment MP. As the aim of this review was to inform an application for the WHO list of essential medicines, the focus of this review was to compare the effectiveness and safety of V, R, and T. Therefore, if we identified additional new drugs for first‐line treatment of multiple myeloma, these were excluded from the network and this review.

We assumed that any participant that meets the inclusion criteria was, in principle, equally likely to be randomised to any of the eligible interventions. We planned to group interventions by evaluating different drug doses together as one drug of interest, according to the product characteristics.

We excluded trials including participants receiving neither V, R, or T (triple or double combination) in at least one treatment arm, and trials including participants receiving no corticosteroid. We excluded trials evaluating the effectiveness and safety of the interventions of interest for supportive treatment during stem cell transplantation, or maintenance therapy, or both. Medications used to treat myeloma in subsequent lines of therapy might be the same as for first‐line treatment, but to ensure that the assumption that participants within the included trials were similar, we focused on first‐line treatment.

Comparison of direct interest

There are few randomised controlled trials comparing directly the effectiveness and safety of double‐ and triple‐combination therapies of the agents of interest (V, R, T) for first‐line treatment of adults with multiple myeloma. Therefore, there is a high degree of uncertainty about whether their effectiveness is comparable, and if not, which one is more effective or safer or both.

Additional interventions to supplement the analysis

Included trials should be comparable in terms of clinical and methodological criteria to ensure the transitivity assumption has been met (Chaimani 2017). Therefore, we did not include any additional interventions.

Types of outcome measures

We included all trials fitting the inclusion criteria mentioned above, irrespective of reported outcomes. We estimated the relative ranking of the competing interventions according to each of the following outcomes.

Overall survival (OS): we used the longest follow‐up available

Progression‐free survival (PFS): we used the longest follow‐up available

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AEs)* (with a special focus on polyneuropathy, neutropenia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, thromboembolism, and infections): number of participants with at least one event

Serious adverse events (SAEs): number of participants with at least one event

Withdrawals due to AEs: number of participants

-

Quality of life (QoL) measured at certain time points with a validated instrument (e.g. EORTC QLQ‐C30)

short (one to three months)

medium (six to nine months)

long (12 months and longer

*The Grades are referring to the severity of AEs according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE): Grade 1 refers to mild AEs; Grade 5 to death related to AEs

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases without language restrictions. We searched for all possible comparisons formed by the interventions of interest. Thalidomide was the first of our agents of interest, which was used for anti‐myeloma therapy. Therefore, we started the search in 1998, as thalidomide had been mentioned for the first time for myeloma treatment in 1999 (Singhal 1999).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 14 February 2019)

Medical subject headings (MeSH) or equivalent and text word terms were used. There were no language restrictions. Searches were tailored to individual databases. The search strategy for CENTRAL is in Appendix 1, the search strategies for MEDLINE in Appendix 2. No member of the author team had access to Embase at the time of the search, so we did not include Embase in our search strategy. We will search Embase in any future updates of this review.

Searching other resources

In addition, we searched the following databases/sources.

-

Study registries (up to 14 February 2019, search criteria in Appendix 3)

EU clinical trials register: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr‐search/search

World Health Organization: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/

Clinicaltrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/

ISRCTN: http://www.isrctn.com/

-

Conference proceedings of annual meetings of the following societies for abstracts, were hand searched for abstracts published since 1 January 2010 up to 14 February 2019. Search criteria in Appendix 4).

American Society of Hematology

American Society of Clinical Oncology

European Hematology Association

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 14 February 2019) for systematic reviews (Appendix 2): Additionally to searching MEDLINE for randomised controlled trials, we searched for systematic reviews and meta analyses on multiple myeloma. We screened all records to identify systematic reviews and meta analyses investigating immunotherapies for transplant‐ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. We screened the included studies reference lists and compared them with the records of our Electronic searches.

We checked reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies and we performed citation searches on key articles.

We contacted experts in the field for unpublished and ongoing trials.

We contacted authors where necessary for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

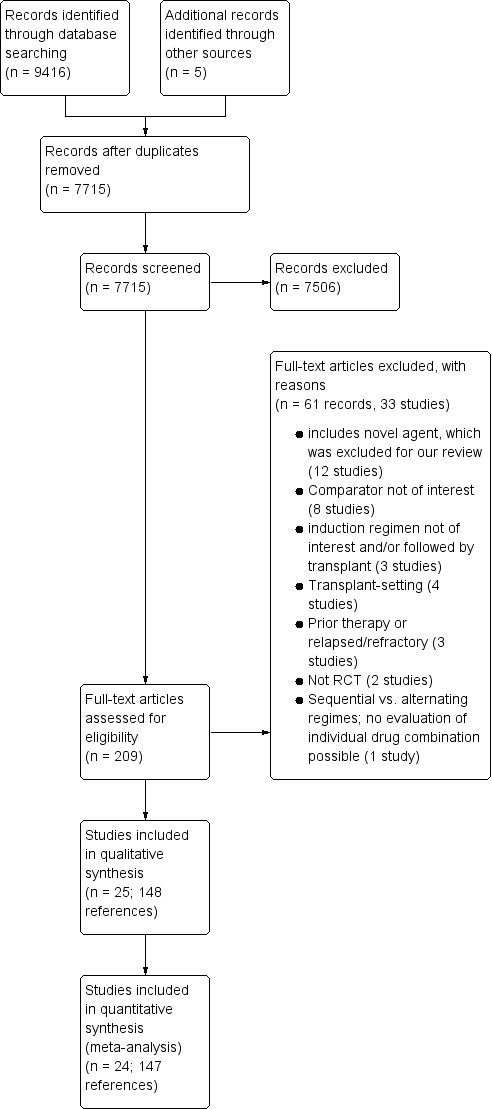

Two review authors (VP, NS) independently screened the results of the search strategies for eligibility for this review by reading the abstracts using Covidence software (Covidence systematic review software). We coded the abstracts as either 'include' or 'exclude'. In the case of disagreement, or if it was unclear whether we should retrieve the abstract or not, we obtained the full‐text publication for further discussion. Independent review authors eliminated studies that clearly did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, and obtained full‐text copies of the remaining studies. Two review authors read these studies independently to select relevant studies, and in the event of disagreement, a third author adjudicated. We did not anonymise the studies before assessment. We included a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Figure 1) in the full review that shows the status of identified studies (Moher 2009) as recommended in Part 2, Section 11.2.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We included studies in the review irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported in a ‘usable’ way.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (VP, BS) extracted data using a standardised data extraction form developed in Covidence (Covidence systematic review software). If the review authors were unable to reach a consensus, we consulted a third review author (NS) for final decision. If required, we contacted the authors of specific studies for supplementary information (Higgins 2011a). We contacted Prof. Jesús San Miguel (contact author of the VISTA trial (San Miguel 2008)) and asked how the primary endpoint time‐to‐progression was defined. The author responded that he is currently travelling, and suggested to search for the definition in the supplemental material of the paper. After agreement has been reached, we entered data into Review Manager (RevMan 2014). We extracted the following information.

-

General information:

author, title, source, publication date, country, language, duplicate publications.

-

Quality assessment:

sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel, outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias.

-

Study characteristics:

trial design, aims, setting and dates, source of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, comparability of groups, subgroup analysis, treatment cross‐overs, compliance with assigned treatment, length of follow‐up.

-

Participant characteristics:

newly diagnosed individuals, cytogenetic subtype, additional diagnoses, age, gender, ethnicity, number of participants recruited/allocated/evaluated, participants lost to follow‐up, type of treatment (multi‐agent standard treatment (intensity of regimen, number of cycles)).

-

Interventions:

type, dose and cycles of treatment; duration of follow‐up.

-

Outcomes:

overall survival (OS), progression‐free survival (PFS), grade 3 and 4 adverse events, serious adverse events(SAEs), polyneuropathies, neutropenia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, thromboembolisms, infections, quality of life, withdrawals due to adverse events.

-

Notes:

sponsorship/funding for trial and notable conflict of interest of review authors.

We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We collected characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate a Characteristics of included studies table in the full review.

Data on potential effect modifiers

We extracted from each included study data on the following.

Intervention and population characteristics that may act as effect modifiers (age, stage of disease, performance score, treatment duration, duration of follow‐up, region)

Year of publication

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (VP, BS) independently assessed risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b), with any disagreements resolved by discussion. In order to rate the certainty of the evidence, risk of bias was assessed per endpoint rather than per study only. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study using the 'Risk of bias' tool in RevMan (RevMan 2014).

We assessed the following for each study.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias): we assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as: low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated). Studies using a non‐random process (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) were excluded.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias): the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated). Studies that do not conceal allocation (e.g. open list) were excluded.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). we assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed methods as: low risk of bias (study states that it was blinded and describes the method used to achieve blinding, such as identical tablets matched in appearance or smell, or a double‐dummy technique); unclear risk of bias (study states that it was blinded but did not provide an adequate description of how it was achieved). Studies that were not double‐blinded are considered to have high risk of bias.

-

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). we assessed the methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as: low risk of bias (study has a clear statement that outcome assessors were unaware of treatment allocation, and ideally describes how this was achieved); unclear risk of bias (study states that outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation, but lacks a clear statement on how it was achieved). Studies where outcome assessment were not blinded were considered as having a high risk of bias. We assessed blinding of outcome assessment in three separate outcome‐categories:

not dependent on outcome assessor: OS;

partly dependent on outcome assessor: PFS;

dependent on outcome assessor: safety outcomes.

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias): we assessed whether primary and secondary outcome measures were pre‐specified and whether these were consistent with those reported: low risk of bias ( study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that were of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way, or the study protocol was not available but it was clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk'); high risk of bias (not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported or one or more primary outcomes were reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data that were not pre‐specified or one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified or one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis, or the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study).

-

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data): we assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data in two separate outcome categories:

time to event data: low risk (censored Kaplan‐Meier curves were provided and study discontinuations were described and balanced between arms); unclear risk (neither Kaplan‐Meier curves, nor flow‐charts were accessible); high risk (‘last observation carried forward’ analysis);

safety data: low risk (safety data was only reported for patients, who received at least one study drug); high risk (intention‐to‐treat population was used to report safety data, however it was stated that participants changed to the other study arm or stopped the study before they received the first dose); unclear risk (it was not described, which population was used to report safety outcomes.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative treatment effect

We used intention‐to‐treat data. For binary outcomes, we extracted number of patients and number of events per arm and calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each trial. For time‐to‐event outcomes, we extracted hazard ratios (HRs) from published data according to Parmar 1998 and Tierney 2007. We checked whether the study authors had checked the proportional hazards assumption. For quality of life (QoL) data, we had planned to calculate continuous outcomes as mean differences (MDs) when assessed with the same instruments; otherwise we had planned to calculate standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs. As reporting of QoL data was scarce, network meta‐analysis was not possible and MDs and SMDs were not calculated. We will do as described in an update of this review.

Relative treatment ranking

We obtained a treatment hierarchy using P scores (Rücker 2015). P scores allow ranking treatments on a continuous zero to one scale (higher P score is indicating the better treatment) in a frequentist network meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies with multiple treatment groups

As recommended in Chapter 16.5.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c), for studies with multiple treatment groups we combined arms as long as they could be regarded as subtypes of the same intervention.

When arms could not be pooled this way, we included multi‐arm trials using an network meta‐analysis approach that accounted for the within‐study correlation between the effect sizes by re‐weighting all comparisons of each multi‐arm study (Rücker 2012; Rücker 2014). For pairwise meta‐analysis, we treated multi‐arm studies as multiple independent comparisons and did not combine these data in any analysis.

Dealing with missing data

As suggested in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c), we took the following steps to deal with missing data.

Whenever possible, we contacted the original investigators to request relevant missing data. We contacted Prof. Jesús San Miguel (contact author of the VISTA trial (San Miguel 2008)) and asked how the primary endpoint time‐to‐progression was defined. The author responded that he is currently travelling, and suggested to search for the definition in the supplemental material of the paper. There we could also find data on PFS. If the number of participants evaluated for a given outcome was not reported, we used the number of participants randomised per treatment arm as the denominator. If only percentages but no absolute number of events were reported for binary outcomes, we calculated numerators using percentages. If estimates for mean and standard deviations were missing, we calculated these statistics from reported data whenever possible, using approaches described in Chapter 7.7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). If data were not reported numerically but graphically, we estimated missing data from figures. We addressed in the Discussion section the potential impact of missing data on findings of the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity within treatment comparisons

To evaluate the presence of clinical heterogeneity, we generated summary statistics for the important clinical and methodological characteristics across all included studies. Within each pairwise comparison, we assessed the presence of clinical heterogeneity by visually inspecting the similarity of these characteristics.

Assessment of transitivity across treatment comparisons

To ensure that the assumption of transitivity was justified, we assessed whether the characteristics of included studies were similar; for example inclusion criteria, study period, dosing, route of administration, co‐medication. Furthermore, we assessed whether the patient characteristics were similar across treatment comparisons; for example age, gender, stage of disease, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score.

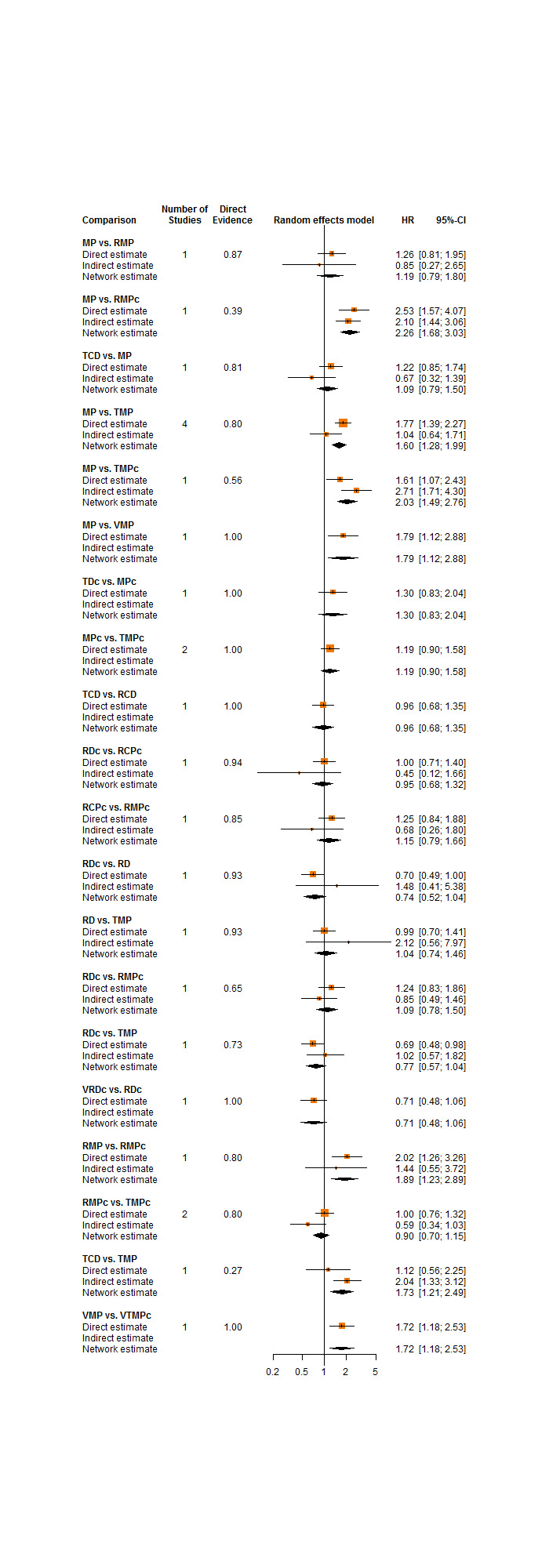

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity and inconsistency

To evaluate the presence of heterogeneity and inconsistency in the entire network, we gave the generalised heterogeneity statistic Qtotal and the generalised I2 statistic, as described in Schwarzer 2015. We used the decomp.design command in the R package netmeta (R 2018; Rücker 2018) for decomposition of the heterogeneity statistic into a Q statistic for assessing the heterogeneity between studies with the same design and a Q statistic for assessing the designs inconsistency to identify the amount of heterogeneity/inconsistency within as well as between designs.

To evaluate the presence of inconsistency locally, we compared direct and indirect treatment estimates of each treatment comparison. This can serve as a check for consistency of a network meta‐analysis (Dias 2010). For this purpose, we used the netsplit command in the R package netmeta, which enables the splitting of the network evidence into direct and indirect contributions (R 2018; Rücker 2018). For each treatment comparison, we presented direct and indirect treatment estimates plus the network estimate using forest plots. In addition, for each comparison we gave the z‐value and P value of test for disagreement (direct versus indirect). It should be noted that in a network of evidence there may be many loops and with multiple testing there is an increased likelihood to find an inconsistent loop by chance. Therefore, we were cautious deriving conclusions from this approach.

If we found substantive heterogeneity and/or inconsistency, we explored possible sources by performing pre‐specified sensitivity and subgroup analyses (see below). In addition, we reviewed the evidence base, reconsidered inclusion criteria as well as discussed the potential role of unmeasured effect modifiers to identify further sources.

Assessment of reporting biases

In pairwise comparisons with at least 10 trials, we examined the presence of small‐study effects graphically by generating funnel plots. As we had no such comparison, we were unable to assess small‐study effects. In future updates, we will use linear regression tests (Egger 1997) to test for funnel plot asymmetry. A P value less than 0.1 will be considered significant for this test (Sterne 2011). We will examine the presence of small‐study effects for the OS only.

Moreover, we searched study registries, to identify completed, but not published trials.

Data synthesis

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

Pairwise comparisons were part of the network meta‐analysis, thus we did not plan to perform pairwise meta‐analysis in addition. In order to outline available direct evidence, we provided forest plots for pairwise comparisons, without giving an overall estimate. Only when data could not combined in a network meta‐analysis, e.g. due to inconsistency, did we performed pairwise meta‐analyses according to recommendations provided in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). We used random‐effects models. We used the R package meta (R 2018; Schwarzer 2018) for statistical analyses. When trials were clinically too heterogenous to be combined, we performed only subgroup analyses without calculating an overall estimate.

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

Where we considered the data to be sufficiently similar to be combined, we performed a network meta‐analysis using the frequentist weighted least squared approach described by Rücker 2012. We used a random‐effects model, taking into account the correlated treatment effects in multi‐arm studies. We assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across the different comparisons. To evaluate the extent to which treatments were connected, we gave a network plot for all outcomes. For each comparison, we gave the estimated treatment effect along with its 95% CI. We graphically presented the results using forest plots, with melphalan/prednisone as reference. We used the R package netmeta (R 2018; Rücker 2018) for statistical analyses.

GRADE

Quality of the evidence

Two review authors independently rated the certainty of the evidence for pre‐selected outcomes (OS, PFS, SAEs, withdrawals due to AEs, polyneuropathies, QoL) and comparisons (RD, TMP, VMP, and VRDc, respectively compared to MP), respectively. We used the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system to rank the certainty of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler Guideline Development Tool software (McMaster 2015), and the guidelines provided in Chapter 12.2 of the CochraneHandbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011a) and specifically for network meta‐analyses (Puhan 2014).

The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grade of evidence.

High = we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate = we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low = our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low = we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning a certainty level to a body of evidence (Chapter 12, Schünemann 2011a).

High: randomised trials; or double‐upgraded observational studies.

Moderate: downgraded randomised trials; or upgraded observational studies.

Low: double‐downgraded randomised trials; or observational studies.

Very low: triple‐downgraded randomised trials; or downgraded observational studies; or case series/case reports.

We decreased grade if:

serious (‐1) or very serious (‐ 2) limitation to study quality;

important inconsistency (‐ 1);

some (‐1) or major (‐ 2) uncertainty about directness;

imprecise or sparse data (‐ 1);

high probability of reporting bias (‐ 1).

'Summary of findings' table

We included a 'summary of findings' table to present the main findings in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, we included key information concerning the certainty of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes OS, PFS, SAEs, withdrawals due to AEs, polyneuropathies and QoL for the treatment combinations of RD, TMP, VMP, and VRDc, respectively compared to MP.

To obtain the median survival times (OS and PFS, respectively) for each of our selected comparisons, we applied the network meta‐analysis hazard ratio (NMA‐HR) to the assumed median survival times of our comparator melphalan and prednisone as recommended in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2019) and by Tierney 2007, e.g.:

median OS for patients treated with intervention x = median survival for patients treated with comparator/ corresponding NMA‐HR (intervention x versus comparator).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered performing subgroup analyses using the following characteristics.

Follow‐up (short‐term (< 5 years) versus long‐term >= 5 years)

Multiple myeloma international staging system (I, II, III)

Age (<75 versus >75)

Region (low‐ and middle‐income versus high‐income)

Subgroup analysis could not be performed due to the characteristics of included studies. The detailed reasons for incomplete subgroup analysis have been outlined in the Differences between protocol and review section of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the robustness of the results, we conducted fixed‐effect pairwise and network meta‐analyses. We reported the estimates of the fixed‐effect only if they showed a difference to the random‐effects model. We had planned to explore the influence of quality components with regard to low and high risk of bias.

Risk of bias sensitivity analysis could not be performed for each outcome due to overall high risk of included studies. The detailed reasons for incomplete sensitivity analysis have been outlined in the 'Differences between protocol and review' section of this review.

Results

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The primary electronic searches performed in June 2018 and February 2019 yielded a total of 9416 potentially relevant references related to the treatment of multiple myeloma. Of these, we identified 1706 as duplicates and excluded 7509 at the initial stage of screening because they did not fulfil our predefined inclusion criteria. The remaining 209 publications were retrieved as full‐text publications or abstract publications for detailed evaluation, out of which 61 (33 studies) were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included: regimen included novel agents which were excluded for our review; comparator not of interest; induction regimen not of interest and/or followed by transplantation; transplant‐setting; prior therapy or relapsed/refractory myeloma; not randomised controlled trial ( RCT); and sequential versus alternating regimens (no evaluation of individual drug combination possible). Five additional records were identified through the screening of reference lists of relevant studies. So finally, 25 studies (148 references) with 11,403 patients were formally included in this review. One study did not report any of our pre‐specified outcomes and could therefore not be included in the main analyses of this review. Overall, we could include 24 studies with 11,337 patients in the main analysis.

The overall number of trials screened, identified, selected, excluded and included are documented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Included studies

A total of 25 trials met our pre‐specified eligibility criteria. The trials included a total of 11,403 randomised participants from Europe, Asia, North‐ and South America, and the Pacific region, with a median age ranging from 52 to 78.5 years. The first patient enrolment started in August 2001 (Ludwig 2009), and two trials are still ongoing (Magarotto 2016; Pawlyn 2017). Twenty trials were published as full texts, four trials were only published as an abstract (Katsuoka 2013; Kim 2007; Mookerjee 2017; Pawlyn 2017), and one trial has only been published as a letter to the editor (Jacobus 2016). Individual patient data of six trials comparing thalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (TMP) versus melphalan plus prednisone (MP) has also been meta‐analysed (Fayers 2011; Palumbo 2013). Presuming higher comparability between the single studies, we extracted all available data from this meta‐analysis as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in the table Characteristics of included studies.

Design

All included trials were RCTs. The majority of trials were open‐label, however two studies (Palumbo 2012; Waage 2010) were double‐blind and placebo‐controlled. Of the 25 included trials, 20 were two‐armed RCTs; and five were three‐armed RCTs (Bahlis 2017; Hungria 2016; Magarotto 2016; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2012). The duration of treatment varied in each study based on differences in the duration and number of treatment cycles and the possibility of continuous treatment or maintenance treatment.

In seven trials, participants received a previously defined amount of treatment cycles (Beksac 2011; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Jacobus 2016; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008).

In seven trials, all participants received maintenance treatment (Durie 2017;Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Stewart 2015; Zweegman 2016).

-

In five trials, only participants in one arm of the study received maintenance treatment:

in the trial of Palumbo 2012, one arm received lenalidomide maintenance treatment, two arms received placebo maintenance;

in two trials one arm received maintenance treatment and one arm did not; whereas both arms received initial treatment until a plateau in response was reached (Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010);

In two trials the experimental arm received maintenance treatment and the control arm did not (Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2014).

In the trial of Bahlis 2017, one arm received continuous treatment, and two arms received a fixed amount of treatment cycles.

In two trials, participants were randomised between maintenance and observation regardless of previous therapy (Morgan 2011; Pawlyn 2017).

Three trials did not provide any information regarding maintenance treatment (Katsuoka 2013; Kim 2007; Mookerjee 2017).

Sample sizes

The smallest trial had a sample size of 18 participants (Katsuoka 2013), while the largest trial had a sample size of 1852 participants (Pawlyn 2017).

Location

The majority of trials were multi‐centre trials and included participants from Europe, Asia, North‐ and South America, Australia, and the Pacific region. Seventeem trials included participants from European Countries (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Morgan 2011; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016), six trials from northern America (Bahlis 2017; Durie 2017; Jacobus 2016; Niesvizky 2015; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015), and Asia (Bahlis 2017; Katsuoka 2013; Kim 2007; Palumbo 2012; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015), respectively; two trials from southern America (Hungria 2016; San Miguel 2008), and one trial from Australia (Palumbo 2012) and the Pacific region (Bahlis 2017), respectively.

Participants

All trials included adults (at least 18 years old) with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) with measurable disease according to either the Durie‐Salmon staging system or International Staging System (ISS). Participants were either ineligible for transplant because they were too old (more than 65 years old) or because of significant co‐morbidities or because stem cell transplantation was not planned. Women of childbearing age had to agree to use adequate contraception.

Interventions

In addition to the differentiation between drug combinations, treatment regimens were differentiated into fixed therapy (first‐line therapy was stopped after a pre‐specified amount of therapy cycles) and continuous therapy (first‐line treatment followed by maintenance therapy, continuous first‐line therapy, or continuous first‐line therapy until a plateau phase (response) was reached). Accordingly, the included participants were randomised to a total of 21 different treatment regimens.

Melphalan and prednisone (MP)

Continuous melphalan and prednisone (MPc)

Lenalidomide plus cyclophosphamide plus dexamethasone (RCD)

Continuous lenalidomide plus cyclophosphamide plus prednisone (RCPc)

Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (RD)

Continuous lenalidomide and dexamethasone (RDc)

Lenalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (RMP)

Continuous lenalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (RMPc)

Thalidomide plus cyclophosphamide plus dexamethasone (TCD)

Continuous thalidomide and dexamethasone (TDc)

Thalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (TMP)

Continuous thalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (TMPc)

Bortezomib and dexamethasone (VD)

Continuous bortezomib and dexamethasone (VDc)

Bortezomib plus melphalan plus prednisone (VMP)

Continuous bortezomib plus melphalan plus prednisone (VMPc)

Bortezomib plus lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (VRD)

Continuous bortezomib plus lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (VRDc)

Continuous bortezomib plus thalidomide plus dexamethasone (VTDc)

Continuous bortezomib plus thalidomide plus melphalan plus prednisone (VTMPc)

Continuous bortezomib plus thalidomide plus prednisone (VTPc)

Outcome measures

Survival outcomes

Out of the 25 trials, included in this review, 24 reported overall survival (OS) (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Durie 2017; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Jacobus 2016; Kim 2007; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Mookerjee 2017; Morgan 2011; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016) and progression‐free survival (PFS) (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Durie 2017; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Jacobus 2016; Kim 2007; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Mookerjee 2017; Morgan 2011; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016).

The Cox proportional hazards model was used by all study authors to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) of survival outcomes. However, it is not clear whether all of the trials checked the assumption of proportional hazards.

Safety outcomes

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were reported in nine studies (Durie 2017; Katsuoka 2013; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Stewart 2015; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016). Reporting of individual grade 3 and 4 adverse events (AEs) was more frequent: polyneuropathy was reported in 18 trials (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Katsuoka 2013; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Waage 2010; Zweegman 2016); infections in 15 trials (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Durie 2017; Facon 2007; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Morgan 2011; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Sacchi 2011; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016); thromboembolism in 14 trials (Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Mateos 2014; Mookerjee 2017; Morgan 2011; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2014; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016); neutropenia in 14 trials (Bahlis 2017; Facon 2007; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Zweegman 2016); anaemia in 14 trials (Bahlis 2017; Facon 2007; Hungria 2016; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Mookerjee 2017; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015; Zweegman 2016); and thrombocytopenia in 12 trials (Bahlis 2017; Facon 2007; Hungria 2016; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; San Miguel 2008; Zweegman 2016). Serious adverse event (SAE) data were available in eight studies (Bahlis 2017; Durie 2017; Jacobus 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2012; San Miguel 2008; Stewart 2015). The outcome “withdrawals due to adverse events” was defined in retrospect and reported in 16 studies (Bahlis 2017; Durie 2017; Hulin 2009; Hungria 2016; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Palumbo 2014; Sacchi 2011; San Miguel 2008; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016).

Quality of Life

Quality of life (QoL) was assessed and reported in four trials (Bahlis 2017; Palumbo 2012; Waage 2010; Wijermans 2010).

See Characteristics of included studies for further details.

Excluded studies

After the screening of abstracts we excluded 7509 references that obviously did not match the inclusion criteria.

In the full text stage, 33 studies, comprising 26 references, were excluded after detailed evaluation due to the following main reasons.

Twelve trials included a novel agent in the treatment regimen, which was excluded for our review (Facon 2017; Facon 2018; Ludwig 2017a; Mateos 2018; NCT01850524; NCT01863550; NCT02586038; NCT03710603; Palumbo 2016; San Miguel 2014; Takezako 2017; Usmani 2014)

Eight trials included interventions not of interest (Anonymous 2003; Facon 2006; Hernández 2004; Niesvizky 2003; Rajkumar 2006b; Rajkumar 2008; Merz 2015; Zonder 2010)

Three trials, the induction regimens were not of interest or followed by transplantation or both (Hejlova 2000; NCT00522392; Morgan 2002)

Four studies were conducted in a transplant setting (Brioli 2014; Kumar 2012; NCT00734877; Harousseau 2003)

Three trials, participants received a prior therapy or were relapsed/refractory (Barlogie 2004; Foa 2007; Offidani 2004)

Two trials were non‐randomised (Montefusco 2013; White 2007)

One trial reported sequential versus alternating regimens; no evaluation of individual drug combinations was possible ( Mateos 2016)

These publications we described under Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The summary of the methodological quality of the included studies for all assessed domains across included studies and per included study are presented in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

In total, 14 of the 25 included studies (56%) reported a central randomisation process and were therefore judged at low risk of bias (Bahlis 2017; Beksac 2011; Durie 2017; Hulin 2009; Ludwig 2009; Magarotto 2016; Mateos 2014; Morgan 2011; Niesvizky 2015; Palumbo 2006; Palumbo 2012; Sacchi 2011; Stewart 2015; Waage 2010). The remaining 11 studies (44%) did not provide enough information to assess sequence generation and allocation concealment and risk of selection bias was therefore judged to be unclear (Facon 2007; Hungria 2016; Jacobus 2016; Katsuoka 2013; Kim 2007; Mookerjee 2017; Palumbo 2014; Pawlyn 2017; San Miguel 2008; Wijermans 2010; Zweegman 2016).

Blinding

As, in general, RCTs in oncology are performed as open‐label trials, we assumed participants and personnel were not blinded unless blinding was explicitly stated. Two of the 25 included trials were (12%) double‐blind trials and were therefore judged to be at low risk of bias (Palumbo 2012; Waage 2010). The remaining 23 studies (88%), were either stated as, or assumed to be open‐label trials and were therefore judged to be at high risk of bias.