Abstract

Dynamin-related proteins are multidomain, mechanochemical GTPases that self-assemble and orchestrate a wide array of cellular processes. Over the past decade, structural insights from X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have reshaped our mechanistic understanding of these proteins. Here we provide a historical perspective on these advances that highlights the structural attributes of different dynamin family members and explores how these characteristics affect GTP hydrolysis, conformational coupling, and oligomerization. We also discuss a number of lingering challenges remaining in the field that suggest future directions of study.

Keywords: Dynamin, dynamin-related proteins, helix, GTPase, bundle signaling element, BSE

Graphical abstract

Dynamin-related proteins are multidomain, mechanochemical GTPases that have low affinity for guanine nucleotides (~10–100 μM), high basal hydrolysis rates (~0.4–1 min−1), and the propensity for self-assembly into high-ordered helical arrays 1. They act in a variety of biological processes and contexts including clathrin-mediated endocytosis (dynamin), mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission (Drp1 and Dnm1) and fusion (OPA1, Mgm1, and mitofusins), vacuolar dynamics and endosome regulation (Vps1), interferon-induced viral restriction (Mx), plant cell cytokinesis and membrane fission (Arabidopsis DRPs), and membrane binding and tethering (bacterial dynamin-like proteins)1–4. While biochemical, biophysical, and cellular studies have provided fundamental functional knowledge, the emergence of atomic resolution models from X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have yielded key insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms that govern DRP activity, particularly with respect to how GTP is hydrolyzed, the interactions mediating self-assembly and conformational coupling during membrane remodeling processes (Fig. 1A). Here we highlight recent structures from across the dynamin family and discuss the broader implications arising from new structural insights.

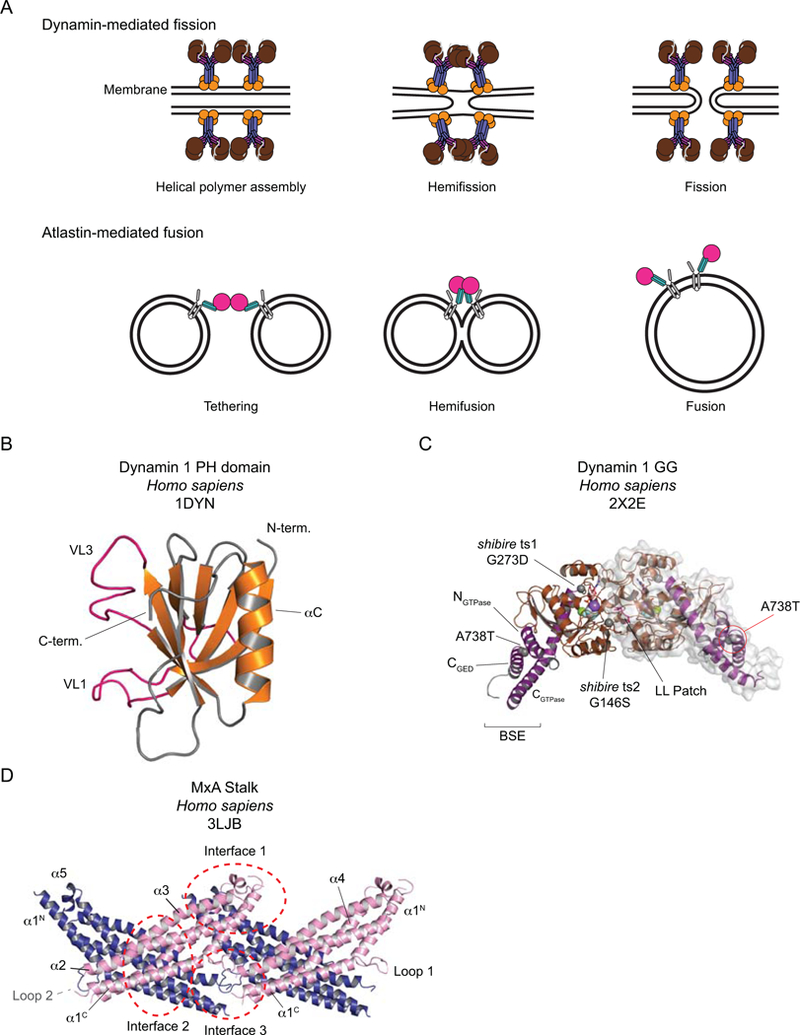

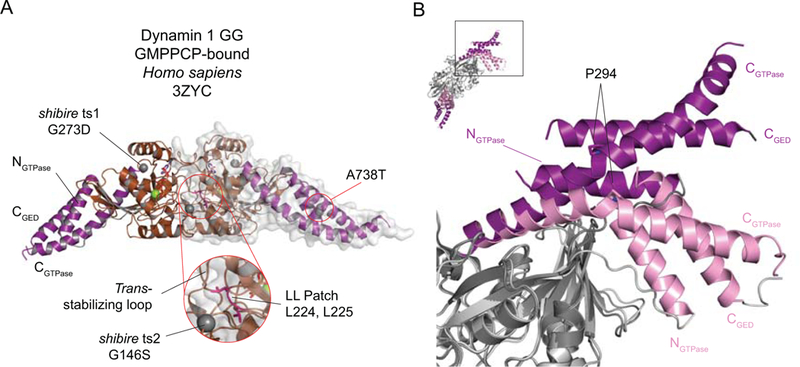

Figure 1.

A. Cartoons of the fission and fusion processes catalyzed by dynamin and atlastin respectively. B-D. The DRP building blocks. B. The dynamin 1 PH domain. The Variable Loops (VL) are shown in pink. C. Dynamin 1 GG, bound to the transition state analog GDP. AlF4-. The BSEs are shown in purple and the G domains in brown. GDP is shown in stick representation, AlF4- (light grey and pale blue), Mg2+ (green) and Na+ (purple) in space-fill. Residues that, when mutated as indicated, generate the shibire ts and sushi mutations are shown in space-fill. The LL Patch with its two leucines is shown in pink. One of the dimer partners is shown with its surface representation. D. The MxA Stalk. The asymmetric unit contains two Stalks (one pink, one blue), assembled via Interface 2. Here two adjacent asymmetric units are depicted, highlighting Interfaces 1 and 3.

X-rays and cryo and structures, oh my!

Traditionally, X-ray crystallography has been the preferred mode of structure determination for achieving an atomic resolution description of the structures of macromolecules. The intricate folding of dynamin family members and their propensity for oligomerization, however, posed a challenge for crystallographic efforts. Despite early success with crystallizing the isolated dynamin PH domain (Fig. 1B)5, the structures of other domains required serendipity, clever construct design, use of purification or crystallization chaperones, or a combination of all these. The GTPase (herein abbreviated G) domains of Dictyostelium discoideum dynamin A (a Drp1 homolog) and rat dynamin, for example, were first purified as fusions to a myosin motor domain and subsequent crystals were phased by molecular replacement using the known structure of the myosin fragment as a search model6,7. In the resulting structural models, an amphipathic α-helix from the C-terminus of myosin fortuitously packs into a hydrophobic groove that is formed by the N- and C-terminal helices of each G domain (NGTPase and CGTPase respectively – see Box 1 for some points of DRP nomenclature). This interaction inspired the design of the first minimal G domain-GTPase effector domain (GED) fusion construct (abbreviated GG), that stabilized the G domain of human dynamin 1 by tethering the C-terminal portion of GED via a short, flexible linker8. GG proved an ideal sample for biochemical and structural studies as it recapitulated dynamin’s basal GTP hydrolysis and could be purified in milligram quantities after heterologous expression in E. coli8. Crystallographic characterization of this construct in complex with the transition state mimic GDP.AlF4- represented a major advance for understanding the mechanisms of basal and assembly-stimulated GTP hydrolysis in that it revealed that (1) only main chain atoms contact the catalytic water directly, (2) a bound cation rather than an arginine finger acts as the charge-compensating element in the transition state, and (3) dimerization across a G domain interface stabilizes the switch regions and properly orients all the catalytic machinery for optimal hydrolysis activity (Fig. 1C)9.

Box 1: Some issues of nomenclature.

The DRPs:

Dynamin, with some exceptions is the name given to the classical or true dynamins, that contain both a PH domain and PRD. Drosophila dynamin is also known as shibire. The gene for Homo sapiens dynamin isoform 1 (dynamin 1) is named DNM1, not to be confused with the fungal and single-cell mitochondrial division DRP, named Dnm1.

Drp1 / Dnm1:

Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) is the mitochondrial division DRP in higher eukaryotes. Homologous proteins in yeast and other single-celled homologs, such as the alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, are usually named Dnm1 (for DyNaMin-related 1). In older literature, Drp1 is occasionally termed dynamin-like protein (Dlp1), although this was also used in a recent structural characterization45. Furthermore, the human Drp1 gene is named DNM1L (for dynamin-1-like) and the structural analysis of its G domain used DNM1L 11. Some additional inconsistencies in nomenclature persist: the GTPase domain from Dictyostelium discoideum dynamin A was one of the first to be solved6 but it is in fact a Drp1 homolog, not a dynamin. Here, we refer to this protein as “Drp1” and we note the inconsistencies and alternate nomenclatures where they arise.

Overall, the whole family is often termed the dynamin-related protein family (DRP), which sadly, has the same initialism as Drp1, one of its most-studied members. For this reason, more recently the initialism DSP, for dynamin superfamily protein, has come into use. We retain the DRP initialism here.

The DRP Bits:

BSE:

The three-helix bundle found in true dynamins and close relatives that consists of two helices that flank the GTPase domain primary sequence (NGTPase and CGTPase) and a helix (CGED) from the end of the GED. The BSE has a key function in intramolecular signaling and possibly force transfer as a result of GTP hydrolysis.

G domain structural elements:

We use the nomenclature for the G domain secondary structural elements that was adopted in the first report of the structure of a dynamin G domain7.

Insert A:

An insert of 25–50 residues within the G domains of Drp1, Dnm1 and Vps1 (but not dynamins or Mx proteins). The insert follows the β2 strand in the G domain. In the case of Drp1 it has also been named the 80-loop as it is centered around residue 80 in the primary sequence11. Where present, it is often disordered in structures of G domains but has been partially modeled in some cases. It is the site of alternative splicing.

Insert B / Variable Domain / Loop 4:

DRPs that lack a PH domain have instead an insert of variable length instead between Stalk helices α3 and α4. In Vps1, the region is known as Insert B and is of length ~75 residues. In Drp1, it is usually referred to as the Variable Domain (VD) and is extensively spliced in higher eukaryotes, with lengths of ~85-~122 residues. In Mx proteins, this region is short (~48 residues) and is termed Loop 4 (L4). In general, these regions are of low complexity though some secondary structure elements may be present.

Dynamin-specific loop:

The 14-residue loop between β6 and αC in the G domain. In the G-G dimer, this segment becomes structured and helps to stabilize the G4 loop. It is conserved in Drp1, Dnm1, and Vps1 but partially conserved in Mx proteins.

LL Patch:

Leucines 224 and 225 in the dynamin G domain, located in the loop between α4 and β6. In the G-G dimer interface, the LL patch aids in the stabilization of Switch 2 in trans.

Trans-stabilizing loop:

A 12-residue loop between β4 and α3 in the G domain. Positions a conserved aspartate (D180 in human dynamin 1) across the G-G dimer interface to stabilize the conformations of switch I and the catalytic glutamine and serine in the P Loop.

Loop 1:

An ~14 residue loop within Stalk helix α1. Mutations in several residues in and around Loop 1 impair assembly and some mutants are disease alleles. In the DRP crystal structures, Loop 1 is typically poorly ordered.

Loop 2:

A short (~8) residue turn connecting Stalk helices α1 and α2. In the crystal structures it is typically disordered. Mutations in and around this loop severely impair or abolish higher-order DRP assembly. Many of the DRP crystal structures relied upon point mutants or more serious engineering at this site to generate crystallizable protein.

Hinge 1:

In the paper describing the structure of Cyanidioschyzon merolae Dnm1 (cmDnm1)65, Hinge 1 refers to the connections between the BSE and the Stalk. Hinge 1 therefore consists of two chains: the linkers between the CGTPase and Stalk α1 helices and the Stalk α4 and CGED helices. These are therefore termed Hinge 1a and 1b respectively. The same nomenclature is used for the hinge connecting the “neck” and “trunk” of BDLP 77, where the neck and trunk are functionally homologous to the BSE and Stalk.

Hinge 2:

In the cmDnm1 paper, Hinge 2 is the equivalent of the proline 294 hinge in dynamin 1, which is the fulcrum around which the CGTPase rotates to generate the open and closed BSE conformations. Hinges 2a and 2b have been proposed in the chains connecting the BDLP GTPase to the neck, functionally the equivalent as the fulcrum between the BSE and GTPase in the dynamins.

The successful GG design was duplicated to examine the catalytic regions of other dynamin relatives, including Arabidopsis thaliana DRP1A10, Drp1 (named DNM1L in the study) (see Box 1)11, MxA12 and Vps113. Similar approaches have also been successful in the structural characterization of the outer mitochondrial membrane fusion DRP Mitofusin 114–16.

The first structural characterization of the “Stalk” of a dynamin – comprising the helical segments of the Middle Domain and GED – was unexpectedly obtained during attempts to crystallize full-length MxA (Fig. 1D)17. The recombinant protein suffered unintended proteolysis at some point during purification and/or the crystallization process. Importantly, the Mx Stalk provided the first insights into the conserved interfaces critical for dynamin higher-order assembly.

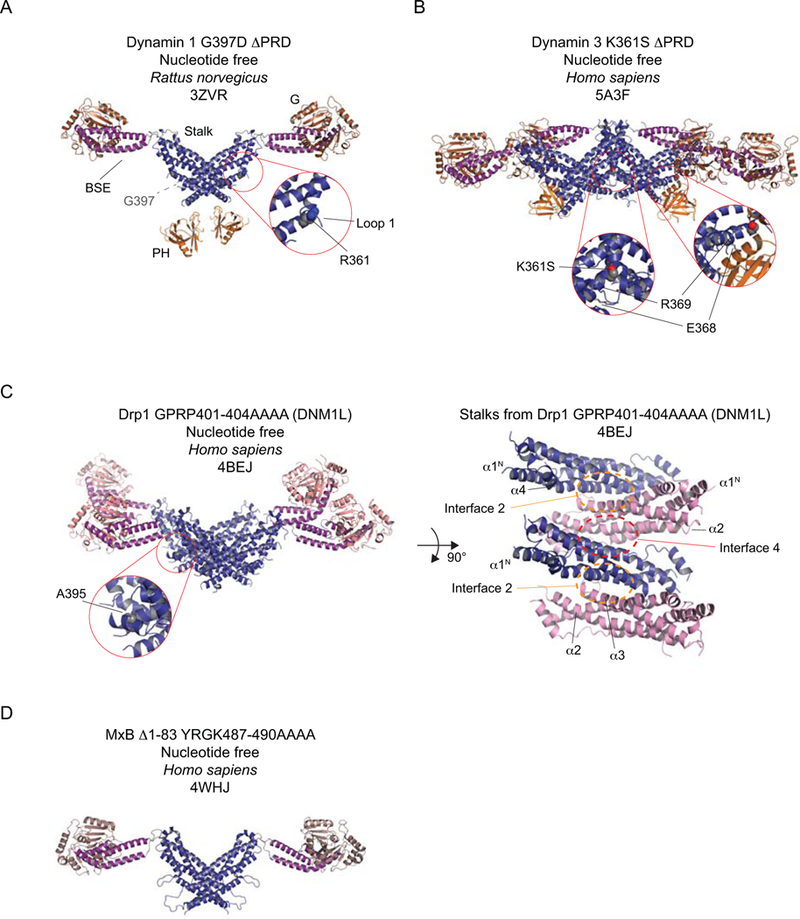

How these domains were organized in the context of the full-length dynamin remained unclear owing to the discontinuity between the available structural models. This problem was eventually overcome by making use of mutations that perturbed self-assembly to varying extents. The first mutants (R361S and R361A) were identified in unrelated mutagenesis screens hunting for potential trans-acting, catalytic arginine fingers. These Middle Domain substitutions were impaired in self-assembly in solution but could still organize into helical structures in the presence of suitable lipid templates18. By contrast, G385D in yeast Dnm1 forms stable, assembly-deficient dimers that lacked cooperative GTP hydrolysis in vitro, a readout for self-assembly19, while A395D in Drp1 precluded assembly beyond the tetrameric building block20. Crystallization of similar assembly-deficient mutants, obtained either by design or by further systematic screening, yielded intact structures of a C-terminally truncated form of human dynamin 1 (ΔPRD)21, rat dynamin 1 ΔPRD (Fig. 2A)22, full-length human mitochondrial Drp1 (Fig. 2C)23, full-length human MxA24 and full-length human MxB (Fig. 2D)25. The subunits adopt an extended conformation with the G domain and BSE at the end of an all-helical Stalk, as initially predicted from small-angle X-ray scattering experiments26. In dynamin, a PH domain is also associated with each Stalk but the linkers between Stalk and PH are disordered. All these crystal structures to date are nucleotide free and, with the exception of the Drp1 structure (Fig. 2C), all form linear arrays in the crystal lattice that are driven by Stalk interactions.

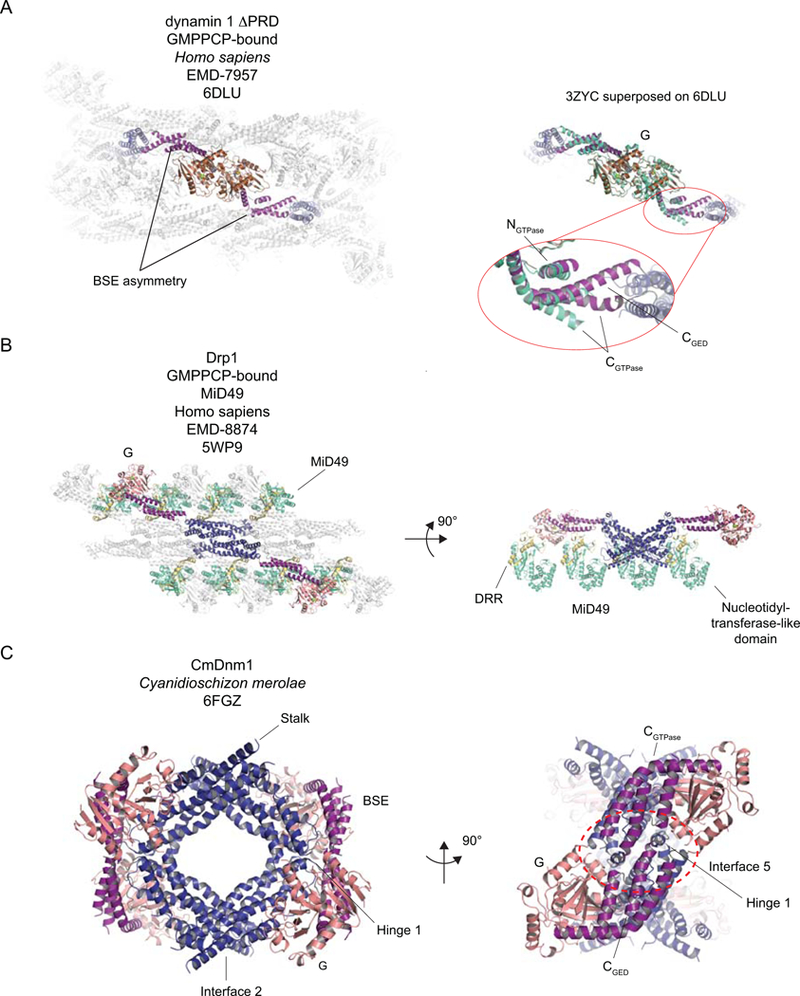

Figure 2.

Selected structures of dynamin and its closest homologs, Drp1 and MxB. A-D The Stalks and BSEs in Drp1 (C) and MxB (D) are highly conserved with those in dynamin (A, B) and are therefore depicted in the same color (Stalk – deep blue; BSE – purple). Some functionally significant sequence differences exist in the Drp1 and MxB G domains when compared to that of dynamin. This is reflected in the slightly different hues used for the respective G domains. The PH domains of the dynamins are depicted in gold. A. Rat dynamin 1 G397D ΔPRD. R361, when mutated, is assembly deficient and is shown in space-fill. B. The human dynamin 3 K361S ΔPRD tetramer. K361S is shown in space-fill. E368 and R369 form contacts with the PH and are mutated in some disease-associated alleles of dynamin 2. C. Left. Human Drp1 with a GPRP->AAAA mutation in Stalk Loop 2. A395, which is assembly-defective when mutated to D, is shown in space-fill. Right. The Stalk region from the structure of Drp1. Alternate Stalks are colored in blue and pink to accentuate the Interfaces. The BSEs and G domains are not shown to improve clarity. In A-C, the insets enlarge the indicated regions. D. Human MxB with a deletion of its N-terminal extension (Δ1–83) and a YRGK->AAAA mutation in Stalk Loop 2.

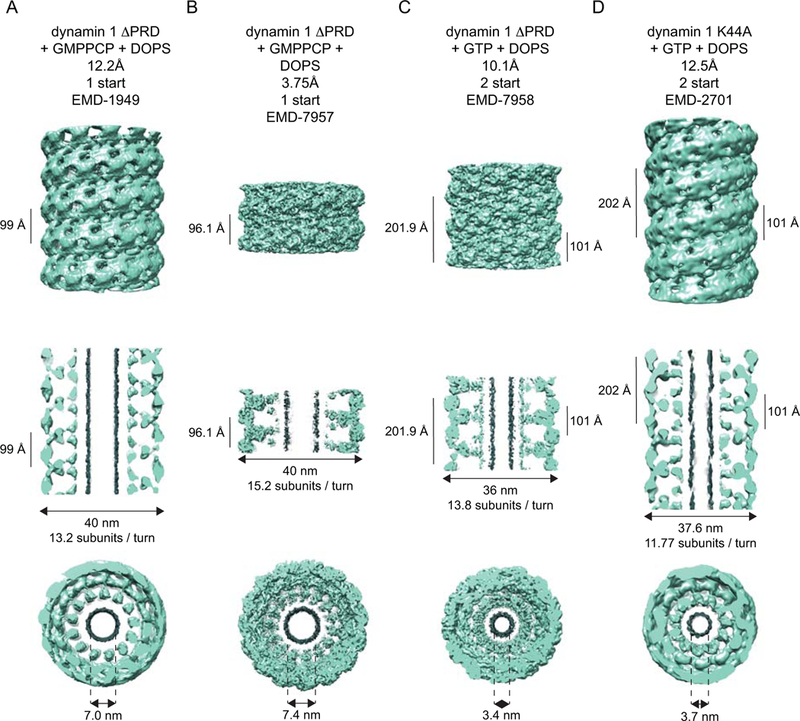

Self-assembly underlies the functional output of dynamin-related proteins. Understanding how they form higher-order structures is therefore essential for understanding their mechanisms of action. While the propensity to oligomerize was problematic for crystallography, this property naturally proved advantageous for cryo-EM. Purified dynamin spontaneously forms rings, spirals and short helices in buffers of low ionic strength27 and helical arrays in the presence of anionic lipid scaffolds28,29. Utilizing a truncated form of human dynamin 1 (ΔPRD), early cryo-EM studies used Fourier-Bessel30 and iterative helical real space reconstruction31,32 methodologies to generate three-dimensional helical reconstructions of the lipid-bound assembled polymer in the absence and presence of the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP (Fig. 3A). While both structures exhibit right-handed, one-start helical symmetry, the inner luminal diameter of the helical assembly shrinks from 20 to 7 nm upon the addition of GMPPCP with a concomitant decrease in the number of subunits per turn (from 14.2 to 13.2) (Table 1). Naturally, these reconstructions acquired the descriptive monikers of “constricted” and “non-constricted”. Characterization of a full-length GTP-bound transition-state-defective human dynamin 1 mutant (K44A) revealed a different subunit arrangement: An alternate 2-start helical symmetry accompanied with a further constriction of the inner luminal diameter to 3.7 nm (Fig. 3D)33, reaching the theoretical limit (~4 nm) wherein the asymmetric distribution of membrane stress would promote spontaneous membrane scission via a hemifission intermediate34–37.

Figure 3.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of dynamins. A-D depict three views of each of the dynamin reconstructions that are deposited in the EM Databank: a side-on view (top row), a central slice (middle row) and an end-on view (bottom row). The central slice straddles the tube’s maximum diameter. Density ascribed to lipid is colored in grey. A. 12.2 Å reconstruction of human GMPPCP- and DOPS-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD, contoured at 1.44 σ. B. 3.75 Å reconstruction of human GMPPCP and DOPS-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD, contoured at 2.51σ with a step size of 4. C. 10.1 Å reconstruction of human GTP- and DOPS-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD, contoured at 3.01 σ. D. 12.5 Å reconstruction of human GTP- and DOPS-bound dynamin 1, contoured at 1.39 σ. DOPS – di-oleoyl phosphatidylserine.

Table 1.

Helical parameters of assembled DRPs

| DRP | Ligand | Template | Resolution (Å) |

Start | Hand | Pitch (Å) |

Subunits / turn |

Outer Diameter (nm) |

Luminal Diameter (nm) |

Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hs dynamin 1 ΔPRD1 | GMPPCP | DOPS | 23 | 1 | Right | 94 | 13.2 | ~40 | Fourier-Bessel | |

| Hs dynamin 1 ΔPRD2 | None | DOPS | ~20 | 1 | Right | ~106 | 14.2 | 50 | IHRSR | |

| Hs dynamin 1 ΔPRD3 | GMPPCP | DOPS | 12.2 | 1 | Right | 99.3 | 13.2 | 40 | 7 | IHRSR |

| Hs dynamin 1 K44A ΔPRD4 | GTP | DOPS | 12.5 | 2 | Right | 202 (inter-strand – 101) |

11.8 | 37 | 3.7 | IHRSR |

| Hs dynamin 1 ΔPRD5 | GMPPCP | DOPS | 3.75 | 1 | Right | 96.4 | 15.2 | 40 | 7.4 | IHRSR |

| Hs dynamin 1 ΔPRD5 | GTP | DOPS | 10.1 | 2 | Right | 201.9 (inter-strand – 101) | 13.8 | 36 | 3.4 | IHRSR |

| Sc Dnm16 | GMPPCP | 90% PE + 10% PI or 100% PS | 30 | 2 | Right | 288 (inter-strand – 144) | 24 | 129 | 89 | IHRSR |

| Hs Drp17 | GMPPCP | 70% GalCer + 30% DOPS | 20.8 | 1 | Right | 127 | 10 | 51.4 | IHRSR | |

| Hs Drp17 | GMPPCP | 88% GalCer + 12% CL | 21 | 1 | Right | 130 | 9 | 49.6 | IHRSR | |

| Np BDLP8 | GMPPNP | E. coli extract | 11 | 11 | Left | ~703 (inter-strand ~64) | ~20 | 50 | 10 | IHRSR |

| Hs MxB9 | 4.6 | 1 | Right | 49.4 | 6 | 27.5 | 5.5 | IHRSR | ||

| Ct Vps110 | GMPPCP | 11 | 1 | Right | 157 | 14.9 | 44.4 | IHRSR |

Hs – Homo sapiens; Sc – Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Np – Nostoc punctiforme; Ct – Chaetomium thermophilum

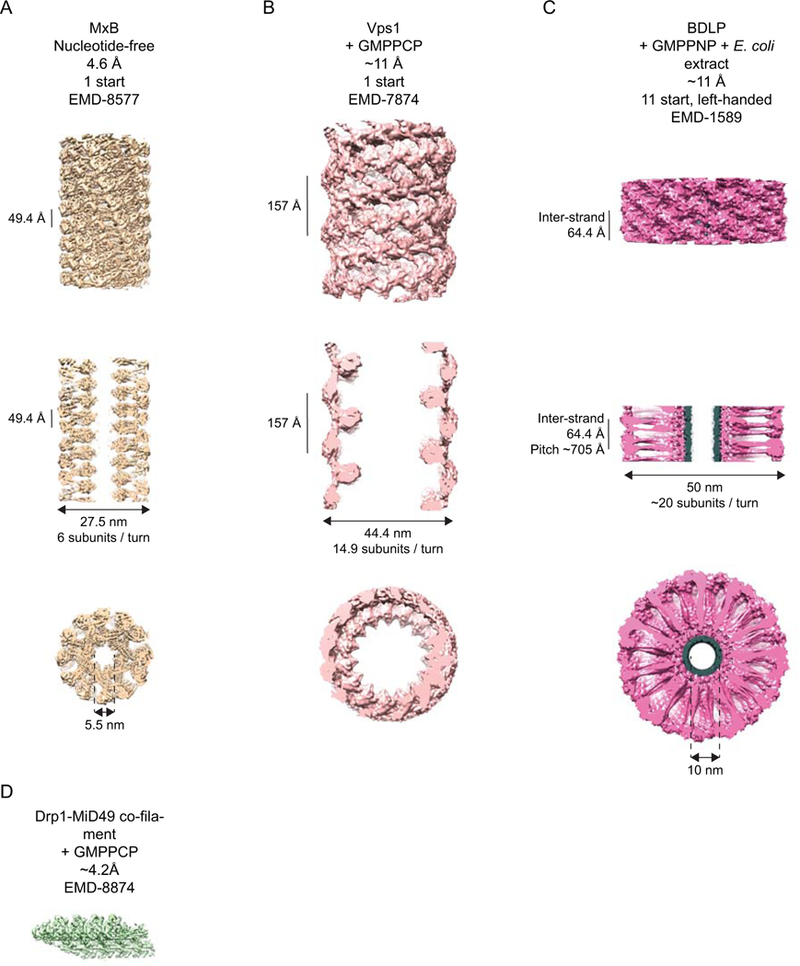

Cryo-EM studies of other dynamin-related proteins also revealed nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements and unique helical symmetries. GMPPCP-bound Dnm1 forms 2-start helices on lipid templates with outer and inner diameters of 129 and ~90 nm respectively. Addition of GTP yields significantly narrower tubes with outer and inner diameters of 59 and 19 nm, underscoring Dnm1’s organizational and conformational flexibility38 (Table 1). Drp1 assembles into right-handed, 1-start helices with outer diameters of 51.4 and 49.6 nm on lipid nanotubes in the absence and presence of cardiolipin, respectively, and with a somewhat larger pitch than was observed for dynamin (~130 vs. 99 Å)39. Vps1 helical assemblies are also right handed, with an even larger pitch of 157 Å (Fig. 4B) (Table 1)13.

Figure 4.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of non-dynamin DRPs that are deposited in the EM Databank. A-C depict three views of the helical reconstructions of MxB (A), Vps1 (B) and BDLP (C): a side-on view (top), a central slice (middle) and an end-on view (bottom). A. The 4.6 Å reconstruction of human MxB, contoured at 2.30s. B. The ~11 Å reconstruction of GMPPCP-bound Chaetomium thermophilum Vps1, contoured at 2.43σ. C. The ~11 Å reconstruction of GMPPNP- and lipid-bound Nostoc punctiforme BDLP, contoured at 1.42 σ. Density ascribed to E. coli lipid is shown in grey. D. The ~4.2 Å reconstruction of the GMPPNP-bound Drp1-MiD49 co-filament, contoured at 2.52 σ with a step size of 4.

Computational docking of available domain crystal structures into these low-resolution envelopes yielded pseudo-atomic models of dynamin21,22,32, Dnm123,38, Drp139, MxA 17,24, and Vps113. Importantly, these revealed how each assembly orients G domain dimerization between subunits in adjacent helical rungs to promote stimulation of GTP hydrolysis.

With the advent of direct electron detectors and improved algorithms for image correction and processing40, the amount of raw data that can be rapidly collected by cryo-EM has exploded. Consequently, it has become possible to address challenges that have long hampered generation of high-resolution helical reconstructions. One difficulty is due to the inherent flexibility of DRP helices, as manifested by variations in pitch and diameter. Abundant data have permitted careful diameter sorting, improving the homogeneity of the input helices that are used for the reconstruction. Long-range helical imperfections also limit the useable information in the power spectrum of the helix, leading to difficulties in indexing, which is a necessary step in generating initial models for the iterative reconstruction, though some brute-force real-space search procedures have been successful in identifying helical parameters. The results of these advances and others are that near atomic resolution reconstructions of lipid- and GMPPCP-bound human dynamin 1 ΔPRD (3.75Å – Fig. 3B)41, Drp1-MiD49 co-filaments (4.2Å – Fig. 4D)42 and MxB polymers (4.6Å – Fig. 4A)43 have recently been achieved by cryo-EM. These models have supported the generation and refinement of detailed atomic models for how the DRPs assemble to generate their respective higher-order assemblies. In all cases, extensive Stalk interactions via three interfaces, similar to those observed in the crystal structures of the dynamins and MxB, stabilize the assembly. The importance of these interfaces has repeatedly been demonstrated for various DRPs by biophysical, biochemical and cell biological approaches and some mutations that disrupt these are known to be responsible for human disease. Beyond that, the atomic resolution reconstructions offer a wealth of novel insight into how the individual DRP domains interact within and between protomers in their respective assemblies and how the basic biology of the DRP may be manipulated by self-assembly or by accessory proteins. Box 2 gives a concise overview of the history and current status of models of membrane fission by dynamin.

Box2: A brief history of scission models.

Understanding of dynamin as the fission catalyst has evolved over time. The first models described dynamin strictly as a mechanochemical enzyme, functioning either as a “poppase” that expanded like a spring29, a “pinchase” that squeezed and constricted the deeply invaginated neck of a clathrin-coated pit31, or a “twistase” that, coupled with tension, could exert rotational forces to sheer the membrane in a GTP hydrolysis manner109. More sophisticated biophysical studies argued that fission might instead be driven by partial disassembly of the dynamin polymer35,110,117, curvature-dependent changes in elastic energy at the edge of the dynamin polymer111 or the tilting of the PH domains within short metastable dynamin collars127,129. These studies also argue that dynamin assembly and constriction induce regions of localized membrane stress and high curvature35,36,108, which asymmetrically strains the inner monolayer of the membrane neck to a greater degree35,37. This ultimately promotes formation of a hemifission intermediate if the inner luminal diameter of the neck approaches the bilayer thickness (∼4 nm)35,129. Biochemical and structural characterization of conformationally trapped assemblies reaching this physical limit have suggested that asymmetry of the BSEs and PH domains constrain the degrees of freedom afforded to the subunits within the polymer and that within this context GTP hydrolysis could promote global rearrangement of the helical symmetry, generating a scaffold that is more favorable for hemifission33,41. Still, the wealth of the structural, biophysical and biochemical insights is broadly consistent with two partially incompatible models for fission: constriction by assembly, where constriction to a hemifission intermediate precedes a distinct disassembly step that is coupled to fission, and a ratchet model, where repeated cycles of GTP hydrolysis and BSE conformational changes progressively constricts the membrane to full fission3. Recent computational modeling has predicted that a rotation of the assembled dynamin helix around its longitudinal axis may also be essential50. The observed tilting of PH domains and the development of BSE asymmetry may represent the real-world implementation of this proposed rotation. Additional challenges have emerged and will doubtless inform refinements or revisions to the model in future. These include questions regarding the potential significance of 1- and 2-start helices, both of which can be formed under certain conditions, the significance or partial or closed rings and how the BSE asymmetry is generated and whether this may reflect an asymmetry in GTP hydrolysis.

Here, we discuss the implications derived from the wealth of structural and biochemical observations, particularly as they relate to the DRP building blocks and how they interact with each other to support the extraordinary functional diversity of the DRP family.

The BSE - not so BS after all

The GG structure confirmed the architectural organization of Bundle Signaling Element (BSE), a proposed intramolecular signaling module comprised of the NGTPase, CGTPase, and CGED of human dynamin 1 (see Box 1). Together these segments form a three-helix bundle that buries an extensive, highly conserved hydrophobic interface8,9. Mutations within the bundle core perturb assembly-stimulated GTP hydrolysis and dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission in vitro and impair late stages of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in vivo8,9. The choice of nomenclature was multifunctional. It reflected not only effects of perturbations on the underlying biochemical properties of the dynamin but at the time also represented a sardonic joke about the incessant urge to rename and rebrand everything with a sexy acronym: BSE also meant “bullsh*t element”.

Ironically, this structural motif proved mechanistically important as it undergoes a dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational change: a rotation of ~69° that was immediately dubbed the dynamin ‘power stroke’9. Further crystallographic comparison of GG in the context of dynamin 1 revealed that the BSEs adopt an open conformation in the ground state (Fig. 5A), projecting away from the G domain, and then rotate downward into a closed conformation in the presence of a transition state mimic (Fig. 5B). This motion is facilitated by a conserved proline hinge (P294 in dynamin 1) and occurs with a concomitant tilting of the G domain’s central β-sheet. In the closed conformation, residues along the outer face of the NGTPase helix contact β2, β2A and β3, with the latter extending into Switch 2, suggesting how the nucleotide state can be relayed into the BSE conformation (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

A. Dynamin 1 GG bound to GMPPCP. The BSEs are shown in purple and the G domains in brown. Green spheres depict Mg2+ ions and GMPPCP is shown in stick representation. The sites of the shibire ts and sushi mutations are shown in space-fill. The LL Patch is shown in pink with the two leucines in stick representation. The inset enlarges the indicated region. One of the dimer partners is shown with its surface representation. B. The BSE conformational change. The different conformations of the BSEs in the GMPPCP-bound (purple) and GDP.AlF4--bound (pink) GG structures. The remainder of the structures are shown in dark grey (GMPPCP) and light grey (GDP.AlF4-). Proline 294, a key pivot point for the CGTPase conformational shift, is shown in stick representation. The inset shows the orientation of the superposed GG structures and the boxed area shows the region depicted in the main panel.

The BSE position in other DRPs reflects a conformational coupling with the G domain active site and is sensitive to the nucleotide analog present. GMPCP-bound GG structures adopt an “open” BSE conformation11–13 while GDP bound versions of dynamin44, MxA12, and Arabidopsis thaliana DRP1A10 are in the “closed” conformation, as is a nucleotide-free form of human Drp111. The BSEs are similarly closed in the nucleotide-free full-length structures of dynamin, Drp1, MxA and MxB21–25. Interestingly, the bundles in GG constructs engineered from Arabidopsis thaliana DRP1A (Yan et al., 2011), Drp145 and Chaetomium thermophilum Vps1 13 are in the open conformation with the transition-state mimic GDP.AlF4-. These differences suggest either that the conformational changes are tailored to the unique biological functions of different DRPs or, alternatively, that the open and closed conformations may be overridden by the crystallization conditions.

Genetic evidence from Drosophila melanogaster further supports a critical role for the BSEs in vivo. Temperature sensitive mutations (shits1 and shits2) in the shibire gene, the Drosophila dynamin homolog, lead to a rapid-onset but readily reversible paralysis46. EM analysis of the affected shibire mutant synapses show an accumulation of trapped endocytic intermediates47. The shits1 mutation (G273D) is located in a tight turn upstream of the CGTPase helix (Fig. 1C) where the glycine normally occupies a pocket created by residues from the G domain αC and strand β6. Other residues would not be tolerated by the constraints at this position, with the resulting structural perturbations affecting the nearby BSE more significantly at elevated temperatures. shits2 (G141S), in contrast, lies in a sharp turn immediately following Switch 2. A glycine at this position increases the range of available backbone conformational freedom, which may be necessary to appropriately orient Switch 2 at the G-G dimer interface. The shits2 substitution impairs assembly-stimulated GTP hydrolysis48, likely due to defects in folding and/or G domain dimerization. This defect can be fully suppressed by several intragenic mutations, collectively known as suppressor of shibire (sushi) mutations49. One of these mutants (A738T) (Fig. 1C) disrupts the internal hydrophobic core of the BSE while another (T749I) introduces a hydrophobic residue downstream of the BSE and may impede BSE packing. Perhaps BSE disruption in the sushi mutations counterbalances the reduced GG dimer formation in shits2 by dampening the efficiency of the BSE conformational shift or by preferentially stabilizing one of its conformations.

The recent reconstruction of lipid-and GMPPCP-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD provides an atomic resolution snapshot of the conformation of assembled dynamin (Fig. 3B, Fig. 6A)41. The assembly is, as expected, stabilized via the Stalk interactions. Furthermore, the G domains form the large, canonical G-G interface observed in the GG crystal structures. However, a marked asymmetry in BSE conformation is introduced across the G-G dimer (Fig. 6A)41. While one BSE across the G-G dimer adopts a conformation approximately midway between the open and closed conformations observed in the GG crystal structures, the conformation of the other is novel: a 35° “wrong way” kink is introduced in the CGTPase helix, around T292-P294. This moves the base of the BSE into a conformation not observed in any crystal structure. The reconstruction therefore captures a previously unanticipated intermediate on the pathway of dynamin conformational changes which will necessitate an update to the earlier view of a symmetric power stroke. This may be consistent with the recent proposal of a tangential rotation of the dynamin assembly around the helical axis, that is capable of generating a membrane torque50. The PH domains are of lower local resolution in the assembly, but the emerging model may be that generation of BSE asymmetry may transfer forces from the formation of the G-G interface to the underlying membrane. Indeed, the BSE asymmetry may also permit dynamin helical assembly in the absence of lipid.

Figure 6.

A. The BSE asymmetry across the G-G interface in assembled, GMPPCP- and lipid-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD. Left. The atomic model of the helical reconstruction (EMD-7957 and PDB 6DLU). Two dynamin protomers are shown colored according to the color scheme used in Figure 1: G domain – brown; BSE – purple; Stalk – deep blue; PH – gold. Remaining dynamin protomers are shown in pale grey. The BSE asymmetry is highlighted. Right. To accentuate the BSE asymmetry in the reconstruction of the GMPPCP- and lipid-bound dynamin 1 ΔPRD, the model of the GMPPCP-bound dynamin 1 GG (consisting of G domain and BSE) crystal structure (green-cyan, PDB 3ZYC) is superposed onto the colored G-G dimer shown on the left. The site where the kink in the CGTPase helix is introduced is shown in the detail. B. The model of the human GMPPCP-bound Drp1-MiD49 co-filament. The highlighted Drp1 dimer is colored according to the scheme used in Figure 1: G domain – salmon (to distinguish the structural differences with the dynamin G domain); BSE – purple; Stalk – deep blue. The MiD49 molecules are shown with the nucleotidyltransferase domains colored in green-cyan and the Drp1 Recruitment Region (DRR) in yellow-orange. Right. The full filament viewed from above. The highlighted Drp1 dimer is assembled via Stalk Interface 2. Other Drp1 protomers within the filament are colored in light grey and are rendered partially transparent to permit visualization of the MiD49 molecules. Right. A 90° rotated view of the model. All the transparent Drp1 dimers have been removed for clarity, as have the MiD49 molecules interacting with the “front” of the filament, from this view. This permits the four interaction interfaces MiD49 has with assembled Drp1 to be appreciated. C. Cyanidioschizon merolae Dnm1 (CmDnm1), in closed conformation. The coloration is the same as for Drp1 in B. Left. An overview of the inhibited tetramer with the location of Hinge 1 highlighted. Right. A 90° rotated view to emphasize the inhibitory Interface 5. Where relevant, green spheres depict Mg2+ ions and nucleotides or analogs are shown in stick representation.

The Stalk: The key to assembly

The first structural characterization of the Stalk of a DRP was that of MxA17 (Fig. 1D). It is an anti-parallel four-helix bundle comprising three helices from the Middle Domain and one from the first part of the GED. The middle (α1-α3) and GED (α4) helices being separated by a flexible loop (Loop 4) that is unresolved in the available crystal structures. Stalk monomers themselves assemble into linear filaments using 3 interfaces, the largest being Interface 2 (~1,700 Å), lying approximately half-way down the Stalk length. Disruption of this interface precludes higher order assembly.

The MxA Stalk shares sequence homology with the analogous regions from dynamin, Drp1/Dnm1 and Vps1. Similar linear oligomers, assembled via the same Stalk interfaces, were observed in the crystal structures of nucleotide-free dynamin 1 ΔPRD21,22 and of both full length MxA and MxB24,25. In all these cases, Stalk Interface 3 was disrupted, either by point mutation or using more severe alterations, to generate protein that could be crystallized. The linear filaments were used to explain the in vitro assembly deficiency of various dynamin and Dnm1 point mutants, some disease-associated. One exception to the linear Stalk filaments seen in dynamins was observed in the crystal structure of nucleotide-free, Drp1 where the Stalks (and the rest of the molecules), stacked via a previously unobserved interface (Stalk Interface 4), opposite Interface 2 (Fig. 2C)23.

A challenge was reconciliation of the linear filaments observed in the crystal lattices with the then available lower resolution helical reconstructions of dynamin. In development of the pseudo-atomic models of assembled dynamin and MxA, Interface 2 was assumed to be invariant due to its relative size. Given the consequences of mutagenesis of the various interfaces on self-assembly, the models of helical assembly proposed introducing a tilt and twist at Interfaces 1 and 3 to accommodate the helical geometry observed in the assemblies. This model received support with the presentation of the crystal structure of the tetramer of an assembly-impaired dynamin 3 ΔPRD mutant (K361S)51 (Fig. 2B), which has a milder assembly-deficiency than was used for the dimeric dynamins18. In this case, the crystal lattice is not built up from linear filaments resulting from assembly at the three Stalk interfaces. Instead, the asymmetric unit consists of two dimers, themselves assembled via the invariant Interface 2, which assemble into the tetramer via an altered interaction at Interfaces 1 and 3. At Interface 1, the two dimers are rotated with respect to one another, when compared to the linear filament, thus pushing the bases of the Stalks closer to one another, at Interface 3. Interface 3 therefore becomes an elaborate interface involving the bases of two Stalks (one from each dimer: those not participating in Interface 1) and the loop (Loop 1) connecting the N- and C-terminal halves of Stalk helix α1 (the Stalks that contribute to Interface 1). In this structure, the full interface is seen, in contrast to the structures of the dimeric dynamins, Drp1 and MxA, where the Stalk Loop 1 and Loop 2 at the base of the Stalk are in general poorly ordered. It also demonstrates why mutation of any of the highly conserved gly residues in Loop 1 and Loop 2 should be particularly assembly-deficient.

The requirement for conformational flexibility at Interface 1 received further experimental support with the presentation of the atomic resolution reconstructions of MxB (Fig. 4A)43 and dynamin 1 ΔPRD (Fig. 3B)41. Furthermore, Drp1 G362D, which harbors a mutation within the Stalk L1 (connecting the N- and C-terminal halves of Stalk helix α1), thereby disrupting Interface 3, assembles into closed rings. In the presence of GMPPCP, stable rings were obtained of this mutant, which permitted the reconstruction of the predominant, 12-membered form42. In this case, Interface 2 was, indeed, conserved in conformation but extensive tilting at Interfaces 1 and 3 was observed to account for the turn between adjacent dimers.

Regulation of DRP assembly: A major source of variation

What prevents inappropriate assembly of dynamin or other family members? In the case of dynamin, a key pre-structural insight came from analysis of dynamin 2 mutations associated with Centronuclear Myopathy or Charcot-Marie-Tooth52. Several of these disease-causing substitutions cluster in the C-terminal alpha helix of the dynamin PH domain (known as PH αC) (see Fig. 1B) and “uncouple” stimulation of GTP hydrolysis from lipid binding26, suggesting that the PH domain may be a regulator of self-assembly. PH αC interacts with residues along the α1C helix of the Stalk (see Fig. 2B) in the dynamin mutant dimer crystal structures21,22. The contact residues on the Stalk (E368, R369) are also mutated in disease-associated alleles of dynamin 221,52. Furthermore, removal of the PH domain via proteolysis or protein engineering yields dynamin constructs that self-assemble in the absence of lipid altogether51,53 (our unpublished observations). Access to Interface 3 as controlled by the PH domain thus appears to be a critical means of regulating dynamin assembly, especially in the absence of nucleotide. The relatively small size of this interface may explain the sensitivity of dynamin self-assembly to changes in salt conditions and pH. Current models suggest that PH domain binding to PI(4,5)P2 weakens the PH-Stalk interface, thereby exposing Interface 3 and promoting oligomerization.

Unlike dynamin, Drp1 lacks a PH domain and instead has an extensively spliced, low complexity Variable Domain (VD) in its place (discussed further below and see Box 1). Functionally the VD is analogous to the dynamin PH domain in that it enhances membrane association and is thought to regulate self-assembly. The VD is particularly efficient where the membrane template contains the dimeric phospholipid cardiolipin54–56. Accordingly, reconstructions of Drp1 assemblies formed in the presence of lipid templates containing cardiolipin display additional density at the membrane surface that has been attributed to the VD39. Cardiolipin is typically an inner mitochondrial membrane component and only becomes enriched in the outer mitochondrial membrane at inner and outer membrane contact sites57 or under certain conditions of mitochondrial injury58, however, suggesting mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 may require additional factors. In mammalian cells, proteins anchored in the mitochondrial outer membrane, such as MFF (Mitochondrial Fission Factor) and the related adaptors MiD49 and MiD51 (Mitochondrial Dynamics), act in this capacity59–62. Co-filaments formed with MiD49 and Drp1 in the presence of GTP or GMPPCP display a unique linear morphology that is distinct from other Drp1 assembles (Fig. 4D, 6B)42,63. In this arrangement, Drp1 subunits associate with each other via the same three Stalk interfaces that stabilize the crystal packing of dimeric dynamin but each Drp1 monomer, additionally, contacts four independent MiD49 molecules. The geometry of the interactions is such that MiD49 can only engage adjacent Drp1 G domains, via its DRR (Drp1 Recruitment Region) when the BSEs are in the open conformation, as is the case in GTP- or GMPPCP-bound Drp1. Addition of GTP triggers disassembly of these co-filaments and promotes the formation of short, curved filaments that close into rings, consisting only of Drp1, in a time-dependent manner42. Perhaps adjacent linear filaments on the mitochondrial surface stimulate GTP hydrolysis, by lateral formation of G-G dimers, with the resulting buckling of the filaments initiating Drp1-mediated constriction (see Box 3).

Box3: A fresh look at mitochondrial constriction.

A recent study42 reported the structure of linear co-filaments of GMPPCP-bound Drp1 with the mitochondrial Drp1 receptor MiD49. These filaments themselves assemble into a triangle via novel, asymmetric G domain interactions at the vertices such that the surfaces of the G domains, which face outward on dynamin helical assemblies, face the interior of the filament. Incubation with GTP results in collapse of the trimer of co-filaments into individual curved filaments and closed rings. These lack density for MiD49. While it is currently unknown whether the G-G interactions responsible for trimer formation occur at the surface of the mitochondrion, the co-filaments do suggest novel models for mitochondrial constriction, or the initial constriction.

In the linear co-filaments, the G domains are held in the fully open conformation by interactions with the soluble part of MiD49. Superposition of the GMPPCP-bound dynamin G-G dimer onto a G domain in the filament shows that, in this conformation, G-G interfaces cannot form due to severe steric clashes with adjacent G domains in the linear Drp1 filament. Adjacent filaments may therefore be able to co-exist without forming G-G interfaces, unless MiD49 is absent. If MiD49 is absent, the G domain can close with respect to the BSE and curvature in all the filaments may be triggered. A key question therefore is the stoichiometry of MiD49/51 on the surface of the mitochondrion when compared to Drp1. This will govern whether linear or curved filaments will form or whether the G-G interfaces can form. It may also influence whether Drp1 rings or helices form.

It is noted that formation of closed Drp1 rings observed in the study may sever one of the mitochondrial membranes if both are compressed simultaneously. After this, it is tempting to speculate that Drp1 helices may form on the remaining narrower tubule for the final constriction, in a manner perhaps independent of MiD proteins. Alternatively, a dynamin may make this final scission step.

An additional interface observed between MiD49 and Drp1 in the co-filament is regulated by phosphorylation on a conserved serine at the base of Stalk helix α4, which inhibits mitochondrial fission in vivo42,64. Finally, two assembly-deficient disease-associated Drp1 alleles, which mutate conserved glycines in the loop (loop L1) separating the N- and C-terminal halves of Stalk helix α1 and known to be involved in Stalk Interface 3 in the assembled filament, also disrupt an additional interface with MiD49 in the assembled co-filament42. Clearly, MiD49, via its many interfaces with Drp1, regulates multiple aspects of Drp1 assembly.

Together, these observations raise the tantalizing possibility that Drp1 receptors can dictate the type of assembly Drp1 forms. Moreover, receptor heterogeneity, localization and distribution throughout the cell may have significant implications for where and how Drp1 functions.

A novel closed conformation

Analysis of Dnm1 from the alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae (cmDnm1) provides further insight into the flexibility surrounding regulation of Drp1 assembly. Like other Drps, cmDnm1 self-assembles in vitro into curved filaments or closed rings in a concentration-dependent manner. The crystal structure of cmDnm1, however, revealed a novel closed conformation (Fig. 6C)65. The conformation of the BSEs captured in this structure is, as in all nucleotide-free dynamin structures, in the closed state. However, in contrast to the existing dimeric and tetrameric dynamin, Mx and Drp1 structures, an additional conformational change is observed in the short linker region connecting the BSE CGTPase and CGED helices to the tops of the Stalks (named Hinge 1 in this study – see Box 1). Overall, the observed Hinge 1 rotation of 95° compared to the nucleotide-free Drp1 structure allows the cmDnm1 GTPase domain and BSEs to fold against the Stalk helices. Furthermore, the back of the now-closed Hinge 1 forms a novel large interface (named Interface 5) with the back of a symmetry-related GTPase domain, of size 2,359 Å2 65, with the distal ends of two BSEs interacting across the symmetric interface (Fig. 6C). As the basic building block of the crystal remains a cmDnm1 dimer, formed by the conserved interaction at Stalk Interface 2, each dimer also participates in two novel Hinge 1 interfaces, such that the closed conformation consists of a dimer of dimers, in a diamond-shaped conformation. The closed Hinge 1 linker lies in close proximity to a conserved arginine in Switch 1 (Arg61). Although the nucleotide binding site is not occupied in the structure, the proximity of this hinge to the nucleotide pocket does suggest how release of the cmDnm1 from the closed state may be coupled to nucleotide loading. While the closed structure is highly reminiscent of the closed BDLP structure66, it will be of interest to see whether this packing and Interface 5 is conserved and used in other dynamin family members. It is of note that the linker connecting the CGTPase helix to the Stalk in higher-eukaryotic Drp1 sequences (Hinge 1a) is shorter than it is in Dynamins and yeast Dnm1 (four versus eight residues) and three residues shorter than that seen in cmDnm1 (7 residues). Furthermore, dynamins have two prolines in Hinge 1a, the first invariant and the second conserved in all dynamins except Drosophila, whereas higher eukaryotic Drp1 sequences have one, at an approximately conserved location equivalent to the first one in the dynamin Hinge 1a, and yeast Dnm1s have none. Hinge 1b (connecting the Stalk to CGED) is conserved in length in all dynamins and Drps, though has conserved hydrophobic residues in higher eukyaryotic Drps that are absent in dynamins and Dnms. It is unknown whether these variations impact flexibility at Hinge 1 and, indeed, whether members of the DRP family have different propensities for a Hinge 1-closed state. Intriguingly, the tops of the Stalks in the closed tetramer are in close proximity and interact in an additional, novel manner: instead of forming the canonical Stalk Interface 1, required for helical and filament assembly, the tops of the Stalks interact via their backsides, permitting formation of the closed tetramer (Fig. 6C). Whether this is conserved is an exciting, open question.

Strays, waifs, and wannabes: an existential crisis of what defines a dynamin

Classical definitions of what constitutes a dynamin relied on a co-occurrence of several structural and functional features in one polypeptide chain. These included an N-terminal “large” G domain, helical stretches divided between a Middle Domain and a “GTPase effector domain”, cooperativity in GTP hydrolysis upon self-assembly, lack of identifiable GAPs and GEFs, and affinities for GTP and GDP in the low micromolar range29,48,67,68 that are markedly lower than the picomolar affinities recorded for small signaling GTPases69,70. Dynamin family G domains measure at approximately 300 residues and contain conserved GTP-interacting sequence motifs (G1-G4)71. They are also distinguished by a high basal GTP hydrolysis that can be stimulated further by oligomerization29,72. Whereas ras-like G proteins act as molecular switches to modulate cellular signaling, dynamin family members exert mechanochemical functions in a variety of contexts.

The simultaneous presence of all, and later some, of these characteristics historically earned membership of the dynamin superfamily1, which swelled to include examples from prokaryotes and eukaryotes alike. In the absence of structural information, many of these proteins were invoked as proxies to explain the molecular mechanisms underlying human dynamin activities in membrane remodeling. This even extended to members whose functions remained unknown and those that preferentially hydrolyze ATP or have smaller GTPase domains. With the multitude of structural models now available, it is possible to revise the existing classification scheme in a manner that reflects the unique structural features of the individual family members more accurately. We take an overtly bottom-up structural approach, describing conservation of structural elements and differences in enzymology and assembly amongst the family members. Alternative phylogeny or function-driven categorizations can also be envisioned and the interested reader is directed to an outstanding recent review4.

True dynamins

True, prototypical dynamins exhibit a number of defining features (Fig. 2A–B). Fundamentally, GTP hydrolysis relies on G domain dimerization to optimally position the catalytic machinery. Catalysis employs a bound cation as the charge-compensating element rather than a canonical arginine finger. Main chain carbonyls in Switch 1 and a conserved P-loop serine coordinate the charge-compensating cation. Importantly, no side chains make direct contact with the catalytic water, with only a conserved P-loop glutamine providing an indirect interaction via an additional bridging water (Fig. 7). Basal GTP hydrolysis in these enzymes cannot be disrupted without perturbation to the overall protein fold and/or nucleotide binding as a consequence. A conserved “dynamin-specific loop” and a separate LL Patch (see Fig. 5A) within the G domain stabilize the nucleotide pocket and dimer interface while the G4 motif conferring nucleotide specificity is distinguished by the sequence TKxD. The BSEs of true dynamins are clearly separated from the Stalk as a short helical bundle and undergo significant nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements around a conserved proline hinge. At the base of the Stalk, the true dynamins have a PH domain with an intact PH αC helix that preferentially binds PI(4,5)P2 and regulates self-assembly. Following the CGED helix, true dynamins harbor a low-complexity proline and arginine rich domain (PRD) of ~120 residues that mediates interactions with a variety of effector proteins. True dynamins readily self-assemble into right-handed 1- or 2-start helices in the presence of lipid and GTP and catalyze membrane scission reactions in a hydrolysis-dependent manner that are essential for cellular uptake.

Figure 7.

Active site organization of dynamin family members and related proteins. Structural models of nucleotide bound G domains are shown and labeled with associated PDB codes. Coloring denotes family classification (see text): ‘true dynamin’, chocolate; ‘close relatives’, salmon; ‘Mfns and BDLP’, violet; ‘Atlastin and Sey1’, hot pink. Catalytic residues and main chain carbonyls (superscript ‘O’) in each model are depicted as sticks. Guanine nucleotides are shown as sticks and colored deep olive with magnesium ions shown as green spheres. Where applicable, charge compensating ions are shown as purple spheres and catalytic (H2Ocat) and bridging (H2Ob) waters are shown as red spheres. Both monomers of Hs Mfn1-GDP complex are included to illustrate the alternative conformations of Switch 1. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonding interactions.

Close relatives (Drp1/Dnm1/Vps1)

Close dynamin relatives share similar architectural organization and functional properties but lack the PRD and a genuine PH domain (Fig. 2C). The BSE helices are structurally and functionally distinct from the Stalk and GTP hydrolysis requires the same G domain dimerization and the same catalytic motifs observed in the true dynamins, including the charge compensating cation (Fig 7). Although the dynamin-specific loop is conserved, the LL Patch is replaced with the sequence Val-Ile. These siblings also contain an insert of variable length (Insert A, also known as the 80 loop – see Box 1) after the β2 strand in the G domain. In Vps1, this insert regulates the morphology of helical assemblies 13. Stalk mutations analogous to those characterized in true dynamins yield comparable assembly-deficient phenotypes13,19,42. The extent of stimulation of GTP hydrolysis upon self-assembly, however, is often markedly less pronounced in vitro for these enzymes.

Mx proteins

Mx proteins retain the G domain, Stalk and BSE architecture with a short, distinct BSE that adopts different conformations depending on nucleotide state (Fig. 2D)12. Although critical catalytic motifs in the G domain and the charge compensating cation are conserved, the LL Patch is not (the first residue is replaced by a hydrophilic side chain in some family members) and the dynamin-specific loop is only partially conserved. The G domains in Mx proteins also do not have an Insert A. Mx proteins have N-terminal extensions of 5–85 residues and a low-complexity L4 Loop at the base of the Stalk, both of which have been implicated in the recognition and restriction of viral growth73,74. Conserved Stalk interactions facilitate self-assembly into tight right-handed helices in the absence of lipid (Fig. 4A) (Table 1)43.

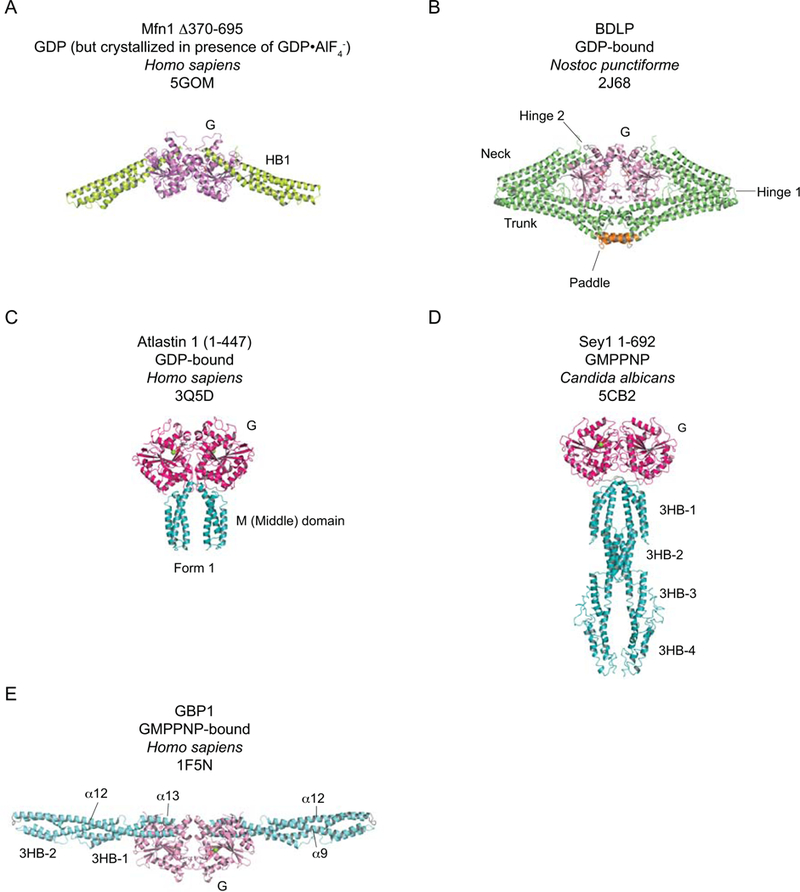

Mfns and BDLP

Mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn1 and Mfn2 respectively) are closely related proteins that are required for fusion of mitochondrial outer membranes in higher eukaryotes2. Loss of either Mfn1 or Mfn2 results in embryonic lethality in mice \75. Yeast have a single functional homolog (Fzo1) and strains harboring a temperature-sensitive fzo1 allele exhibit fragmented mitochondria and quantitatively lose mitochondrial genomes at the restrictive temperature76. Mfns and Fzo1 contain a common domain arrangement that includes an N-terminal G domain, a heptad repeat region (HR1), two transmembrane regions, and a second heptad repeat region (HR2). Structural analysis of a minimal Mfn1 construct containing truncated segments of HR1 and HR2 connected via a flexible linker (here referred to as mini-Mfn1) showed that the G domain is flanked by an extended four-helix bundle (HB1) (Fig. 8A)14,15. The helical segments that make up HB1 are distributed through the Mfn1 primary sequence: two of them lie upstream of the G domain at the very N-terminus, the third immediately follows the G domain, and the final helix is situated at the extreme C-terminus of the protein. As with the minimal GG constructs, mini-Mfn1 is monomeric in the absence of nucleotide but dimerizes through G domain interactions in the presence of GDP.AlF4-, with the G4 contributing to the interface. The HB1 bundles extend out linearly from the G domains – oriented perpendicular to the two-fold symmetry axis – such that the dimer measures 180 Å in length. HB1 rotates downward by 82° in the structure of mini-Mfn1 complexed with GDP.BeF316, mirroring the nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements observed in other DRPs. Thus, while Mfn1 does not have a true distinct BSE, HB1 may be functionally analogous.

Figure 8.

The crystal structures of selected other DRPs. A-B. Mfn1 and BDLP share structural homology and are therefore colored similarly (G domains – pinks; HB1, neck and trunk, as appropriate – greens). A. Human Mfn1 Δ370–695, bound to GDP.AlF4- (only density for GDP is observed). B. GDP-bound Nostoc punctiforme BDLP. The membrane-interacting “paddle” is shown in orange. C-D. Examples of structures from the atlastin/Sey1 subfamily. As these share structural and biochemical features, their G and helical domains are colored similarly (G domains – hot pink; helical domains – teal). C. Human atlastin 1 residues 1–447 bound to GDP. D. Candida albicans Sey1 residues 1–692 bound to GMPPNP. E. Human GBP1 bound to GMPPNP. Significant differences in G domain structural features are noted compared to the dynamin G domain, hence the coloration is distinct. GBPs do not have BSEs but rather have a complex Stalk consisting of two three-helix bundles, sharing a common helix α9, which are connected by a common helix α12 (all colored in aquamarine). Where relevant, green spheres depict Mg2+ ions and nucleotides or analogs are shown in stick representation.

The mini-Mfn1 crystal structures also reveal key features in the G domain that contribute to nucleotide binding and hydrolysis. Mfns and Fzo1 uniquely contain the G4 variant sequence NRWD. The Trp from this motif occludes the nucleotide-binding pocket in the apo structure and reorients upon nucleotide loading, allowing the conserved G4 Asn and Asp to engage of the guanine base for recognition15. His107 was proposed to function as the charge-compensating element based on its proximity to the β-phosphate in the GDP-bound mini-Mfn1 structure (Fig. 5)15. The structure of mini-Mfn1 in complex with the transition-state mimic GDP.BeF316, however, contains a charge-compensating potassium ion that is coordinated by main chain carbonyls in Switch 1 and has H107 flipped away from the phosphates (Fig. 7). The distinct orientations of H107 in the GDP-bound structure thus appear to be an artifact of the non-canonical conformations Switch can adopt in the absence of the required ion cofactor. It is important to note that the H107A mutant impairs mitochondrial elongation and fails to restore mitochondrial morphology in MFN1-deleted mouse embryonic fibroblasts15,16 suggesting it may still play an important functional role.

Mini-Mfn1 also shares significant sequence and structural conservation with the Nostoc punctiforme bacterial dynamin-like protein (BDLP), which contains a G domain, two extended helical bundles (HB1 and HB2), and a helical paddle that replaces the transmembrane regions and associates directly with lipids (Fig. 8B)66. In the absence of nucleotide, BDLP monomers form a tight hairpin wherein HB2 and the paddle fold back toward the G domain, bending around a loose hinge (Hinge 1) that links HB1 and HB2. GDP binding induces BDLP G domain dimerization without altering this compacted conformation66. The paddles also associate and contribute to the dimer interface while the HB1 bundles extend outward, oriented perpendicular to the two-fold symmetry axis in a conformation akin to the apo and GDP.AlF4- bound mini-Mfn1 structures66. BDLP assembly in vitro in the presence of a E. coli lipids and GMPPNP triggers major conformational rearrangements, which unfurls the molecule and reorients HB1 and HB2 in a head-to-tail in a configuration that lies parallel to the two-fold symmetry axis, generating a complex left-handed helical assembly with 11-start symmetry (Fig. 4D) (Table 1)77. Rotation around a second hinge connecting HB1 to the G domain (Hinge 2) plays a critical role in this transition. Interestingly, the resulting HB1 conformation mirrors that seen in the structure of the GDP.BeF3-bound mini-Mfn116. These similarities suggest BDLP and Mfns define a distinct subclass that likely share the same molecular mechanism and comparable functions. It is of note that the HBs in the BDLP helical assemblies do not assemble via interfaces analogous to those observed in Stalk-containing DRPs so the helical architecture is fundamentally different.

While the precise role of BDLP remains unclear, it likely is related to the membrane tethering activities of Mfns78 and the dynamin-like proteins from Campylobacter jejuni79.

Atlastins and Sey1

Atlastins and their yeast counterpart Sey 1 catalyze fusion of ER tubules and are required for the formation of an interconnected reticular ER network80. Metazoan atlastins contain an N-terminal G domain, an extended three-helix bundle (3HB) connected via a flexible linker, two transmembrane regions, and a C-terminal cytoplasmic tail81. In contrast to dynamins, atlastins contain a guanine cap (G5 motif)82,83 that sequesters the nucleotide from the solvent and utilize a conserved arginine finger in the P-loop (R77) as the charge compensating element (Fig. 7)84. GDP-bound atlastin 1 crystallizes in two distinct dimeric forms85,86. One dimer (Form 2) adopts an extended conformation with a minimal G domain interaction surface and the helical bundles extended outward perpendicular to the two-fold symmetry axis. The alternative dimer (Fig. 8C) (Form 1) shows increased association between the G domains with domain swapped helical bundles that are oriented downward, parallel to the two-fold symmetry axis. Structures of human atlastin 1 in complex with GDP.AlF4- or GMPPNP capture a similar domain swapped dimer with a tighter association observed between the helical bundles (Form 3)84. These structures suggest a general model for atlastin function in which the extended Form 2 represents a ‘pre-fusion’ state, with monomers localized in and tethering two distinct membranes, and Forms 1 and 3 represent a ‘post-fusion’ state, where the conformational rearrangement of the 3HBs facilitates membrane fusion. Different biophysical studies and experimental conditions have yielded alternative models for the timing of these conformational changes relative to atlastin’s GTP hydrolysis cycle87–89. Although each is consistent with the respective assays employed, a definitive consensus has yet to be reached in the field.

Despite functional similarity with atlastins90, Sey1 exhibits a number of structural differences (Fig. 8D). The P-loop notably lacks a charge compensating arginine finger and instead contains a QS motif (Fig. 7), which in dynamin acts to coordinate the bridging catalytic water and charge compensating ion9. Each Sey1 monomer also contains four 3HBs that line up end-to-end form an elongated Stalk (Fig. 8D). Structural characterization of Candida albicans Sey1 shows this Stalk undergoes nucleotide-dependent rearrangements that mirror atlastin’s, adopting an extended conformation with GDP and a parallel domain swapped conformation with GDP.AlF4- and GMPPNP91. Only the first helical bundle associates with the G domain throughout these changes, further underscoring a common underlying mechanism.

Guanylate binding proteins (GBPs)

Interferon-inducible GBPs are cytokines that function in innate immunity and coordinate antiviral and antiproliferative responses in cells92. Members also act in regulating proliferation and migration of endothelial cells93. GBPs contain an N-terminal G domain, an extended Stalk composed of a pair of 3HBs oriented end-to-end with an additional long helix (α12) that runs the length of the entire structure, and a short, C-terminal helix (α13) that folds back onto α12 and terminates in an isoprenylation-recognition CaaX motif (Fig. 8E)94. Like atlastins and Sey1, GBPs contain a guanine cap and a G4 motif variant where the last two residues are Arg-Asp83. GBPs undergo nucleotide-dependent dimerization and cooperative activity94 but are unique in that they can further convert GDP to GMP95,96. The mechanistic details underlying these hydrolysis activities were illuminated for human GBP1 using a truncated version of the protein that contains only the G domain. This construct retained the functional properties of the full-length protein and was crystallized in the presence of GMPPNP, GDP.AlF3, GMP.AlF4-, and GMP97, where it forms dimers with all analogs except for GMP). This arrangement is made possible by a conformational change in Switch 2 that prevents steric clashes. The nucleotides are oriented in a head-to-head fashion and the repositioning of S73 (Switch 1) and R48 (P-loop) in cis brings about catalysis in each monomer. S73 coordinates the catalytic water while the R48 serves as an intramolecular arginine finger and the charge-compensating element (Fig. 7). Comparison of the GDP.AlF3 and GMP.AlF4- structures reveals that S73 and R48 also mediate the GDPase activity by the same mechanism. Surprisingly, there are no further conformational changes in the binding pocket and β-phosphate is brought into position by a change in the torsion angles around the ribose ring97.

Recent biophysical characterization of farnesylated hGBP1 suggests that GTP binding releases the modified CaaX motif, setting up a competition between membrane binding and the self-assembly of hGBP1 monomers into ring-like discs that further stack into cylindrical structures98. The former promotes membrane tethering, which is proposed to help clear engulfed pathogens from the cell.

Distant cousins: IRGs and EHDs

The Immunity-Related GTPases (IRGs) are a large family of GTPases that function in innate cell resistance mechanisms that target a variety of intracellular pathogens. They have micromolar affinities for GTP and GDP, exhibit nucleotide-dependent G domain dimerization and can oligomerize, properties they share with all dynamins99,100. Their structures, however, diverge significantly from true dynamins in that they have a shorter G domain – measuring 185 residues in Irga6 – flanked by two all-helical domains101. The structure of the GMPPNP-bound Irga6 dimer revealed that the 3’-OH of the nucleotide analog ribose hydrogen bonds with the same 3’-OH of the nucleotide analog in the dimer partner. Additionally, the ribose contacts Switch 1 of its dimer partner in trans. Additional contacts involve Switches 1 and 2 and the Trans-Stabilizing Loop, giving rise to a small overall interface of 470 Å2 102. Notably, Irga6 is N-terminally myristoylated and this modification is required for its recruitment to parasitophorous membranes in infected cells. Current models propose that recruitment of certain IRG family members to these membranes may cause their disruption92.

Eps15-Homology Domain-containing proteins (EHDs) are often included in the dynamin superfamily owing to their micromolar affinities for nucleotides, self-assembly, stimulated hydrolysis, and roles in membrane remodeling events103. Furthermore, the helical bundle adjacent to the G domain undergoes a significant conformational change, similar to dynamins in general104,105. However, while the EHD catalytic core adopts a G domain fold, these enzymes specifically bind and hydrolyze ATP, rather than GTP, due to a steric occlusion in their nucleotide binding pockets104.

Dynamin’s dirty laundry and remaining challenges

Lipid and template effects and polymer extremes

The isolated dynamin PH domain binds phosphoinositides, particularly PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2, with low micromolar affinities106. Membranes containing either of these phosphoinositides potently stimulate dynamin’s GTPase activity22,107, a convenient experimental readout for self-assembly. The PH domain has a lower affinity for PS (47 μM), which, in turn induces only a 5-fold stimulation of GTPase activity106. Affinities for PC and PE are significantly lower (several hundred μM) and do not stimulate GTPase activity at all. It is therefore clear that the nature of the lipids comprising a membrane may be expected to influence the properties of the dynamin on that membrane. On liposome templates containing PI(4,5)P2, the PH inserts into the membrane with a Variable Loop (VL), which is required for membrane tubulation and subsequent scission108. Dynamin also readily tubulates PI(4,5)P2-containing membranes from lipid or membrane reservoirs in the absence of GTP. Addition of GTP to tubules with dynamin scaffolds can trigger rapid vesiculation109,110. In the absence of nucleotide, dynamin can also assemble on lipid nanotubes of a range of curvatures pulled from membranes and can, furthermore, constrict these35. It can constrict these tubules if the membrane contains PS and no PI(4,5)P2 although supplementation with PI(4,5)P2 accelerates the constriction. It may therefore be that negative charge density of a membrane rich in PS can override the more specific high-affinity interaction with PI(4,5)P2. Alternatively, addition of PI(4,5)P2 may alter membrane rigidity and make it more bendable. On the other hand, PI(4,5)P2 is specifically required for stimulation of dynamin’s GTPase activity when preformed lipid nanotubes are used as the template. PI(4,5)P2-containing nanotubes supported a 1000-fold stimulation of GTPase activity whereas tubes where PI(4,5)P2 is replaced with an increased proportion of PS (to maintain charge density) supported no GTPase activity at all29. The difference in these observations may depend on differences in curvatures for the starting templates. In addition to binding, the global biophysical properties of the membrane template are also criticial for scission. Membrane tension, one component of the elastic energy of a membrane, is essential for fission activity. In vitro constriction of non-anchored templates does not result in scission109,111 and the presence of tension dramatically accelerates scission in vitro3. Consistently, loss of membrane tension in cultured cells traps clathrin-coated pits at the scission step of endocytosis111.

Overall, the precise biochemical manifestations of dynamin assembly, disassembly and scission activities depend intimately on the biophysical and biochemical properties of the lipid templates as a whole, in addition to the composition of the membrane used. All available dynamin helical reconstructions, however, were performed in the presence of liposomes consisting solely of DOPS30–33,41. DOPS liposomes are homogeneous and are experimentally easy to generate and manipulate: more complex, more physiological, lipid mixtures significantly less so. More importantly for the structural work, the assemblies that dynamin forms on tubules generated from DOPS liposomes, when assessed by cryo-EM, are longer, more regular and more amenable to structural characterization than the short, limited structures observed on templates of a more physiological lipid mix110.

Two questions immediately arise from these observations. First – are the extended structures that are formed from lipid reservoirs containing PI(4,5)P2, on lipid tubes pulled from donor membranes or formed from PS liposomes, all in the absence of nucleotide, physiologically relevant or do they represent kinetically trapped assemblies which cannot form in vivo? While there is not yet a reconstruction of a lipid-bound nucleotide-free dynamin of sufficient resolution to unambiguously assess the GTPase and BSE conformations, the lower resolution reconstruction of “non-constricted” dynamin would be consistent with the BSEs being in a closed conformation and no GG dimer formation31. These nucleotide-free helices would be assembled only by Stalk interactions without G-G interface formation. That dynamins can indeed assemble into helical structures lacking the GG interface with the BSEs in the closed conformation was confirmed with the high-resolution structure of MxB43. Consistently, addition of GTP to pre-formed dynamin assemblies on lipids results in scission109,112. When GTP is present, only limited assemblies are formed110 and these are expected to include G-G interfaces, as well as the Stalk interfaces.

Second, are the conformations of the PH domains observed within the helical instructions made using PS liposomes instructive for their conformations on more physiological membranes? The reconstructions of structures of the GMPPCP- and GTP-bound dynamins show that, like the asymmetry of the BSEs across the G-G interface, the PH domains are asymmetric also, with one rather better ordered than the other41, indicating a certain flexibility in the manner of PH domain engagement with the membrane. The local resolutions of the reconstructions at the PH-membrane interfaces are, however, generally low so a clear picture does has not yet emerged.

What about the rings?

Purified dynamin assembles into partial and intact rings when dialyzed into low salt concentrations27, which can be counteracted by the presence of the SH3 domain from either Amphiphysin 1 or 2113. Rings also form in the presence of GTPγS and transition state mimics114 and have similarly been observed for Dictyostelium discoideum dynamin A (a Drp1), Vps1, and human Drp113,42,115,116. Ring formation thus appears to be a general property conserved amongst DRP family members. In the case of Vps1, rings predominate when Vps1 is incubated in the presence of GDP or GDP.AlF4-, whereas the presence of the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP results exclusively in helical assemblies13. Incubation of linear Drp1-MiD49 co-filaments with GTP results in formation of curved filaments and, ultimately, closed Drp1 rings, lacking MiD49, before complete disassembly42 (see Box 3).

The first structural characterization of a DRP ring structure came from Dictyostelium discoideum dynamin A. When treated with a protease inhibitor, two internal dynamin A cysteines are modified, resulting in an enhanced propensity to form rings with 11-fold symmetry116. A Drp1 mutant that disrupts Stalk Interface 3 (G362D) exclusively forms closed rings in the presence of GTP or GMPPCP. GMPPCP-bound rings with 12-fold symmetry were appropriate for reconstruction 42, the enhanced resolution confirming the double-layered structure seen with the Dictyostelium discoideum dynamin A rings. The rings are assembled via Stalk Interfaces 1–3. The BSEs approximate an “open” configuration though the G domains are all monomeric.

These observations together suggest rings may be directly formed in the presence of GDP or via curling of initially linear filaments. A question then arises as to how helices may form at all? In the case of dynamin, lipid binding or the presence of PH domains may promote helical assembly. The Vps1 observations are uncomplicated by the presence of lipid and helices are only observed with GMPPCP. G-G interfaces may therefore be required for helix formation. Consistently, helices are observed when Drp1 is incubated in the presence of GMPPNP, whereas a range of closed rings (with 11–18-fold symmetry) are formed when incubated with GTP, which is presumably hydrolyzed prior to ring formation115. In the absence of G-G interfaces, rings may therefore predominate. Low salt concentrations may remove PH regulation of helix assembly, resulting in dynamin 1 rings.

Does a PH domain make a fission dynamin?

True dynamins, uniquely, have a PH domain at the bases of their Stalks. Hence, PH-mediated regulation of self-assembly by controlling access to Interface 3 is a specialization of endocytic-type dynamins. The PH domain is, moreover, intimately involved in the membrane recruitment and subsequent membrane deformation, hemifission and fission processes 108,117 and some of the biochemical differences between dynamin isoforms 1 and 2 may be due to subtle sequence differences within a PH domain Variable Loop118. Dynamin can also exhibit robust fission in various in vitro assays using model membrane templates28,35,109,110, without a requirement for additional factors.

Is, therefore, a PH domain required for membrane scission or solely for a rather specialized mode of regulating assembly? This question has been addressed most specifically in the context of mitochondrial division in higher eukaryotes, which relies upon dynamins for both fission and fusion events2. Drp1, the mitochondrial division dynamin in higher eukaryotes, lacks a PH domain. While it can still tubulate liposomes, forming decorated structures of diameter ~ 40 nm, scission was not observed119. Hence, it has been proposed that different dynamins may sequentially function in the division of mitochondria, which requires co-ordinated scission of mitochondrial outer and inner membranes120. In this case, Drp1 would function in “pre-constricting” mitochondria and dynamin 2, which bears a PH domain, would be required for the final scission step. Indeed, siRNA-mediated depletion of dynamin 2 results in a hyper-fused mitochondrial network, consistent with an impairment in mitochondrial division120. More recently, it has been reported that mitochondrial and peroxisomal division was still observed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking all three dynamins. Furthermore, Drp1 was able to fragment lipid tubules drawn from a lipid reservoir in a diameter-dependent manner121, in the absence of additional accessory factors or receptors. This direct demonstration of tubule fragmentation by Drp1 suggests other dynamin family members can indeed act as scissionases also. While it may be that classical dynamins are facilitators of scission in higher eukaryotic cells, other PH-less family members may be able to effect scission reactions, at least on certain lipid templates: the templates used in this particular study contained 25 mol % cardiolipin, which may be easier to fragment, for example, than a mitochondrial outer membrane. Consistently, a dynamin where the PH domain is replaced with a stretch of 6 histidines or lysines can still be recruited to anionic lipid templates and can constrict and sever them, in the context of supported bilayers with excess membrane reservoir122. However, the lifetimes of individual constricted helices are significantly extended, which results in a decrease in overall rates of fission. Hence, at least using this membrane model, the PH may be a catalytic enhancer. Clearly, PH domain-containing dynamins are not required in every system as yeast mitochondria divide, even though yeast lack a homolog of a true dynamin and endocytosis from parasomal sacs in the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila uses a Drp1123. It is evident that much remains to be understood about scission activities for non-PH domain-containing dynamins.

What causes assembly stimulation?