Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this report is to describe the presentation, disease course, and management of subacute thyroiditis (SAT) in children. SAT is a rare cause of thyroiditis in children and can be mistaken for acute suppurative thyroiditis, which may be more common in pediatrics.

Methods:

We present a 7-year-old female, who had painful thyroid enlargement, fever, and thyrotoxicosis.

Results:

Laboratory evaluation showed high white blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and free thyroxine levels. Thyroid-stimulating hormone was low. A computed tomography scan of the neck showed intrathyroidal fluid collection consistent with an abscess. She was treated with clindamycin, with no relief of fever and pain. Thyroid ultrasound showed diffuse enlargement of the thyroid lobes with hypoechoic areas, and no fluid accumulation, consistent with SAT. She was treated with intravenous ketorolac with relief of pain and fever, but these symptoms recurred when she was changed to oral ibuprofen. Her symptoms resolved with prednisolone at 1 mg/kg.

Conclusion:

Based on the limited number of reports in the literature, SAT in children appears to be unusual and may be less common than acute bacterial thyroiditis. In pediatric practice it is important to make the distinction between SAT and acute bacterial thyroiditis.

INTRODUCTION

Subacute thyroiditis (SAT), also known as granulomatous or de Quervain thyroiditis, is an acute inflammatory condition of the thyroid presumably caused by a viral infection (1). SAT is more common than acute suppurative thyroiditis (AST) in adults. In contrast, the incidence of SAT is likely lower than that of AST in children (2). The rarity of these conditions in pediatrics and their similarity in presentation lead to difficulties in diagnosis and treatment even to this day. SAT is often mistakenly diagnosed as AST (3,4), and the reverse can also occur (5). Early differentiation is important for prompt treatment to be instituted. Here we report the case of a 7-year-old girl with SAT who was initially diagnosed as having AST.

CASE REPORT

Our case is a 7-year-old, Caucasian girl who was transferred from another facility to the University of South Alabama (USA) Children's and Women's Hospital for the management of AST. She had a 1-week history of anterior neck pain, sore throat, and persistent fever with a maximum temperature of 101°F. Rapid test for flu and Streptococcus pyogenes done by her primary care physician was negative. She was admitted to the outside hospital when her symptoms progressed after 1 week to painful swallowing, hoarseness, heat intolerance, palpitations, and a 5-pound weight loss.

On physical examination she looked ill and had a fever (body temperature of 101°F) and tachycardia (heart rate of 120 beats per minute). She had tenderness over the thyroid gland, which was enlarged about twice the normal size, and had limited neck movement due to pain. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory evaluation showed an increased white blood cell count of 11.6 × 109 cells/L (reference range is 4.0 to 11.0 × 109 cells/L), with 66% neutrophils. She had a negative throat culture. Thyroid function test results were consistent with thyrotoxicosis including thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.01 μIU/mL (reference range is 0.40 to 4.50 μIU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) of 6.1 ng/dL (reference range is 0.8 to 1.6 ng/dL). Thyroid antibodies were negative including thyroid peroxidase antibody of 16 IU/mL (reference range is <20 IU/mL), anti-thyroglobulin antibody of 0.6 U/mL (reference range is <0.9 U/mL), thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin of 107% (reference range is <130%). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased at 99 mm/hour (reference range is <20 mm/hour).

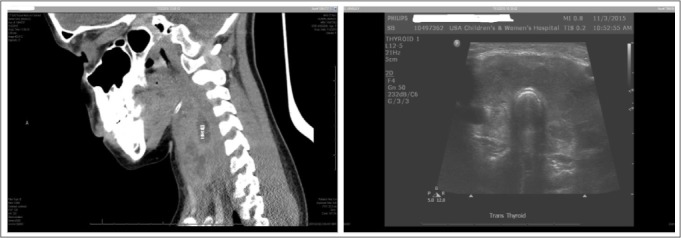

A computed tomography scan of her neck (Fig. 1 A) from the transferring hospital showed a 9 × 21 × 31-mm fluid collection within the thyroid gland, consistent with an intrathyroidal abscess. She was started on clindamycin prior to coming to our hospital but remained febrile. Upon transfer to our institution, thyroid ultrasound was performed showing diffuse enlargement of the thyroid lobes with hypoechoic areas, consistent with SAT (Fig. 1 B). There was no fluid accumulation found, which is what is expected in AST. A barium swallow test was done, and no pyriform sinus fistula was identified. The diagnosis was changed to SAT, clindamycin was discontinued, and she was started on intravenous ketorolac with relief of neck pain and fever and her FT4 decreased to 4.9 ng/dL (reference range is 0.8 to 1.6 ng/dL).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan (A) suggestive of intrathyroidal abscess measuring 9 × 21 × 31 mm. Thyroid ultrasound (B) showing diffuse enlargement of both thyroid lobes with an ill-defined, hypoechoic area.

When she was later changed to oral ibuprofen, her neck pain and fever recurred (maximum body temperature of 103°F), with FT4 increasing to 6.0 ng/dL. She was then started on intravenous methylprednisolone at 32 mg (1 mg/kg), with relief of the above symptoms. After 2 days on methylprednisolone, she was switched to and discharged on oral prednisolone at 30 mg (1 mg/kg). At discharge she had a TSH level of 0.02 μIU/mL, FT4 of 3.5 ng/dL, and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate had decreased to 35 mm/hour. Prednisolone was given for another 2 weeks and tapered over a period of 8 weeks. She had eventual normalization of thyroid function, with 4-week TSH of 4.12 μIU/mL and 10-week TSH of 3.83 μIU/mL. FT4 was 0.92 ng/dL at 4 weeks and 0.85 ng/dL at 10 weeks.

DISCUSSION

Painful thyroiditis can either be AST or SAT, and the conditions have overlapping features which makes distinction between them difficult (5). SAT, a more common cause of painful thyroiditis in adults than AST, is actually rarer than AST in children (2). Firm estimates of incidence are difficult to establish because this condition is described in only a few case reports. Ogawa et al (2) reported a case in 1988 and summarized 6 additional cases. Since then, only a few cases have been reported.

AST and SAT both present with painful thyroid enlargement and usually fever. SAT, which is also known as acute granulomatous thyroiditis or de Quervain thyroiditis, is presumably caused by a viral infection (1). Among the viruses implicated are mumps, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, influenza, echovirus, enterovirus, and coxsackievirus (6). Approximately 50% or more patients may present with clinical and laboratory findings of thyrotoxicosis (5,7). Low-grade fever, dysphagia, history of upper respiratory infection, exquisite neck pain, and elevated sedimentation rate are frequently associated with this condition.

This self-limiting disease often resolves spontaneously but may recur (2,4). The use of anti-inflammatory medicine is frequently necessary to relieve pain and corticosteroids improve the condition dramatically in 24 hours (7), as was noted in our patient. Thyrotoxicosis may persist for 1 to 4 weeks, and this could be followed by a phase of transient hypothyroidism (8). Thyroid ultrasound usually shows an enlarged thyroid and varying degrees of hypoechogenecity and can provide definitive diagnostic information for subacute thyroiditis. Furthermore, it rules out fluid accumulation or an abscess formation (9,10).

Our patient had a computed tomography scan of the neck which suggested abscess, but the thyroid ultrasound did not show such findings, and instead revealed features consistent with SAT. Radioactive iodine uptake typically shows low or absent uptake, and provides help with differentiation from Graves disease, in which the uptake is increased (11). This was not done in our patient but could have been helpful in clarifying the diagnosis.

In children with AST, congenital pyriform sinus patency is common (12). The most commonly isolated organisms from the abscess formation have been Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (12,13). The clinical presentation includes sudden onset of pain with firm, tender swelling involving the lower left anterior neck which moves with swallowing, and fever. The most common laboratory finding is leukocytosis with shifts to the left, and elevated sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Thyroid function tests are typically normal (13,14). Thyroid ultrasound usually reveals left lower lobe swelling and/or abscess formation. Antibiotics are the first line of treatment and should cover both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (15).

SAT is frequently misdiagnosed as AST because of similarities in their presenting signs and symptoms (3,4). In general, thyroid enlargement is localized in AST and diffuse in SAT. In some cases, thyroid enlargement in SAT is localized in the left lobe of the thyroid (2,4,16), which can complicate the presentation, as this is a usual finding in AST. Similarly, there are reports of AST that were misdiagnosed as SAT initially, leading to delay in antibiotic therapy. In one instance, the patient had painful left-sided thyroid enlargement, but was afebrile, had no leukocytosis, and had increased thyroid hormone levels, features typically found in SAT (5).

Management of SAT in children is based largely on adult data and involves using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, and sometimes a beta blocker. There is no recommendation as far as steroid dosing for children; past case reports typically used 1 to 2 mg/kg of prednisone or prednisolone (3,6). Our patient was treated with prednisolone at 1 mg/kg, which quickly relieved the pain and fever.

CONCLUSION

SAT is a rare cause of painful thyroiditis in the pediatric age group, even more rare than AST, which is the opposite of what is observed in adults. SAT and AST have overlapping features and can easily be mistaken for each other. Careful clinical examination and monitoring, laboratory testing, and thyroid ultrasound are invaluable for diagnosis. Radioactive iodine uptake is also helpful in clarifying the diagnosis. It is rare enough that there are no consensus guidelines for steroid dosing in pediatric patients. Previous case reports utilized prednisone or prednisolone at 1 to 2 mg/kg.

Abbreviations:

- AST

acute suppurative thyroiditis

- FT4

free thyroxine

- SAT

subacute thyroiditis

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eylan E, Zmucky R, Sheba C. Mumps virus and subacute thyroiditis; evidence of a causal association. Lancet. 1957;272:1062–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)91438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogawa E, Katsushima Y, Fujiwara I, Iinuma K. Subacute thyroiditis in children: patient report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16:897–900. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2003.16.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchta RM, Price P. Subacute thyroiditis in a 4 1/2-year-old girl. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134:1090–1091. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130230068019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geva T, Theodor R. Atypical presentation of subacute thyroiditis. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63:845–846. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.7.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szabo SM, Allen DB. Thyroiditis. Differentiation of acute suppurative and subacute. Case report and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1989;28:171–174. doi: 10.1177/000992288902800403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engkakul P, Mahachoklertwattana P, Poomthavorn P. de Quervain thyroiditis in a young boy following hand-foot-mouth disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:527–529. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engkakul P, Mahachoklertwattana P, Poomthavorn P. Eponym: de Quervain thyroiditis. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:427–431. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen RP. Serum triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyrotropin during hyperthyroid, hypothyroid, and recovery phases of subacute non suppurative thyroiditis. Metabolism. 1974;23:467–471. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(74)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Kim EK, Kim MJ et al. Ultrasonographic characteristics of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:229–234. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.4.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vulpoi C, Zbranca E, Preda C, Ungureanu MC. Contribution of ultrasonography in the evaluation of subacute thyroiditis [in Romanian] Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2001;105:749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweeney LB, Stewart C, Gaitonde DY. Thyroiditis: an integrated approach. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah SS, Baum SG. Diagnosis and management of infectious thyroiditis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000;2:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s11908-000-0027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paes JE, Burman KD, Cohen J et al. Acute bacterial thyroiditis: a clinical review and expert opinion. Thyroid. 2010;20:247–255. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slatosky J, Shipton B, Wahba H. Thyroiditis: differential diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1047–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook I. Microbiology and management of acute suppurative thyroiditis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardoff R, Luboshitzky R. Transient cold nodule of the thyroid due to localized subacute thyroiditis. Clin Nucl Med. 1989;14:919–920. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]