Abstract

Objectives

To demonstrate a study design that could be useful in low‐resource and violent urban settings and to estimate the prevalence of child violence exposure (at home, community, and school) and child mental health problems in a low‐income medium‐size city.

Methods

The Itaboraí Youth Study is a Norway–Brazil collaborative longitudinal study conducted in Itaboraí city (n = 1409, 6–15 year olds). A 3‐stage probabilistic sampling plan (random selection of census units, eligible households, and target child) generated sampling weights that were used to obtain estimates of population prevalence rates.

Results

Study strengths include previous pilot study and focus groups (testing procedures and comprehension of questionnaire items), longitudinal design (2 assessment periods with a mean interval of 12.9 months), high response rate (>80%), use of standardized instruments, different informants (mother and adolescent), face‐to‐face interviews to avoid errors due to the high frequency of low‐educated respondents, and information gathered on a variety of potential predictors and protective factors. Children and adolescents presented relevant levels of violence exposure and clinical mental health problems.

Conclusions

Prevalence estimates are probably valid to other Brazilian low‐income medium‐size cities due to similarities in terms of precarious living conditions. Described study methods could be useful in other poor and violent world regions.

Keywords: child psychiatry, epidemiology, longitudinal studies, prevalence, violence

1. INTRODUCTION

Violence is a serious public health problem, and the prevention of violence against children and adolescents is a global challenge that deserves efforts from all countries (World Health Organization, 2010). A recent systematic review of population‐based surveys on the prevalence of past‐year violence against children examined data from 96 countries and showed that prevalence of violence was high in both the developing and developed world. In the developing world, more than a billion children aged 2 to 17 years experienced physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence in the previous year (Hillis, Mercy, Amobi, & Kress, 2016).

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations General Assembly, 1989) defines children as individuals under 18 years of age. Different definitions exist for adolescence (Sawyer et al., 2012). The study presented in this article considers children those participants between 6 and 10 years of age and adolescents those between 11 and 15 years of age.

According to the World Health Organization and the United Nations (UN; Butchart & Mikton, 2014), millions of children around the world suffer from the consequences of violence in their homes, communities, and schools. The nonfatal consequences of violence are by far the greatest part of the social and health burden arising from violence. The mental health and behavioural consequences of violence exposure include anxiety, depression, suicide, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol and drug addiction, hyperactivity‐inattention and externalizing behaviours, besides school dropout, and recurrent relationship difficulties. In addition, the Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 (Butchart & Mikton, 2014) evaluated the progress that 133 countries have made in implementing the recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health established in 2002 (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002) and made new recommendations. For instance, at a national level, countries still need to strengthen data collection to reveal the true extent of the problem and to disseminate data gathered on fatal and nonfatal violence to inform planning and action (Butchart & Mikton, 2014).

In 2015, the UN established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015), mentioning that there can be no sustainable development without peace. The Agenda's goals and targets will stimulate worldwide action over the next years in areas of critical importance for humanity including the protection of human rights and efforts to free societies from violence (UN, 2015). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015), a first step in preventing violence is better understanding its magnitude, nature, and consequences. In order to accomplish this first step, a group of researchers from different countries conducted the Itaboraí Youth Study to obtain information on risk (mainly violence exposure) and protective factors for mental health problems in a random population‐based community sample of Brazilians aged 6 to 15 years.

The Itaboraí Youth Study was designed and implemented as a result of the educational‐scientific cooperation established between University of Trømso (Norway) and Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Brazil). Researchers from Columbia University (USA), University of Turku (Finland), Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie (Brazil), and Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Brazil) also collaborated on this study. The main objective of the Itaboraí Youth Study was to examine the impact of violence exposure in the home, community, and/or school on child and adolescent mental health when taking into account a range of potential predictors and protective factors (objective of future articles). The study also aimed to describe types and potential mental health benefits of services and informal support (e.g., family, friends, neighbours, teachers, and religious leaders) received by children and adolescents. Service use included the number of nights in hospitals, alcohol and drug treatment clinics, shelters and juvenile detention centres; attendance in different outpatient clinics or centres; and professional assistance from pediatricians, family doctors or general practitioners, community health workers, social workers, psychiatrists, and psychologists.

The choice of Itaboraí city as our research site was based on three facts. The first fact was poverty—in 2007, 35.2% of the city population were considered poor compared to 18.8% in the State of Rio de Janeiro (United Nations Human Settlements Programe, Petrobras, Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2007). The second fact was violence—in 2006, the city registered a high homicide rate among adolescents (six deaths per thousand in the age group 12–18 years; UNICEF et al., 2009). The third fact was family stress due to an increase in unemployment—in 2008, Itaboraí city had high rates of unemployment, and an unskilled work force was competing with trained professionals coming from other states looking for the new 200,000 jobs that Petrobras (governmental Brazilian oil company) was promising when planning to build a large oil refinery in the city. More recently, Petrobras entered a huge economic crises due to Brazil's biggest‐ever corruption scandal that weakened the country's economy and produced an enormous amount of job losses nationally (Blount, 2015). The procedures to build the oil refinery were interrupted; workers lost their jobs but remained living in the city; and unemployment and criminality rates increased in the area. For instance, from 2013 to 2014, the apprehension of children and adolescents by the police increased 26.3%, and finding a dead body in the city increased 114.3% (Bruno & Pandeff, 2016). These three facts together represent sources of intense and prolonged stress that can have a variety of short‐ and long‐term negative effects on child and adolescent physical and mental health (Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008).

Poverty, violence, and unemployment are frequently affecting a great proportion of the population residing in Brazilian medium‐size cities (100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants; da Silva, 2013). From 1970 to 2000, medium‐size cities multiplied in all Brazilian regions (de Carvalho, 2003). The intense and disorganized territory occupation was marked by inequalities. Areas more distant from the centre had reduced economic value and concentrated a population with precarious living conditions due to social exclusion, environment degradation, deficits in infrastructure (e.g., basic sanitation services), and violence (Alves, 2016).

Regarding the prevalence of violence exposure in low‐ and middle‐income countries, a literature review (Ribeiro, Andreoli, Ferri, Prince, & Mari, 2009) mentioned the study of Avanci, Assis, Oliveira, and Pires (2009) that reported high rates of victimization among boys and girls (6–13 years) at home (63.9% and 53.2%, respectively), at school (42.4% and 44%, respectively), and in the community (31.5% and 21.6%, respectively). Assis, Avanci, Pesce, and Ximenes (2009) presented epidemiological data on the various forms of violence against Brazilian children and adolescents. The authors mentioned two studies: one that evaluated children from 10 Brazilian State capitals and reported victimization by physical aggression in the community (12%) and death threats received by themselves or by a near family member (16%; Cardia, 1999); and another in which mothers reported that their children (6–12 years) had witnessed someone stealing or shooting people (11.4%) and had witnessed a homicide (12.1%; Avanci, Assis, & Pesce, 2008).

Regarding the prevalence of mental disorders in Brazilian children and adolescents, population‐based studies using diagnostic instruments have shown that rates are similar considering those obtained in Brazil and in other countries. A multicentre cross‐sectional study involving a probabilistic sample of schoolchildren from Grades 2–6 (n = 1,676; age: 6–16 years) from four municipalities from four Brazilian regions identified current psychiatric disorders (Paula et al., 2015). Reported prevalence rates were 13.1% for any psychiatric disorder, 7.2% for any anxiety disorder, 5.8% for any disruptive disorder, 4.5% for attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 0.5% for any depressive disorder. These rates were similar (except for attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder) to the rates previously obtained by Fleitlich‐Bilyk and Goodman (2004) in a probabilistic sample of schoolchildren (n = 1,251; age: 7–14 years) from Taubaté city in southeast Brazil. These rates were also very similar (except for any depressive disorder) to the worldwide‐pooled prevalence reported by Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, and Rohde (2015) in a systematic review of the literature on prevalence studies of mental disorders in children and adolescents that used probabilistic community samples and standardized diagnostic measures based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases (41 studies conducted in 27 countries).

The primary objective of this paper is to demonstrate a study design that could be useful in low‐resource and violent urban settings, showing how to conduct a methodologically sound study using appropriately translated instruments, so that other researchers could adapt this strategy to their own context. According to Kieling et al. (2011), child and adolescent mental health research is still needed, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries, including prevalence and longitudinal studies. Filling this gap, the secondary objective of the present paper is to estimate the prevalence of key constructs of the study (e.g., child and adolescent exposure to different types of violence, mental health problems, and symptoms of PTSD) in a population of children and adolescents living in a low‐income medium‐size Brazilian city.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

The Itaboraí Youth Study was conducted in Itaboraí, a low‐income medium‐size city from southeast Brazil, located about 60 km far from Rio de Janeiro, the second largest Brazilian city and capital of Rio de Janeiro State. According to the last Brazilian census (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2010a), the population of Itaboraí is of about 218,000 inhabitants (98% urban) with 32.0% of them under 20 years of age (IBGE, 2010b). Regarding education in the population aged 25 years or older, 51.3% of total residents and 50.8% of female residents did not complete 8 years of schooling (IBGE, 2010c).

This longitudinal study involved a probabilistic community‐based sample of children and adolescents aged 6 to 15 years (n = 1,409 at baseline). Participants included mothers and substitutes (all female) and adolescents (boys and girls) that were interviewed during Waves 1 and 2 with a mean interval of 12.9 months.

2.2. Sampling

Stratified random sampling is used to ensure that a sample is equivalent to the general population in terms of key variables (Norman & Streiner, 1998). Stratification is a common technique applied for many reasons such as gaining precision in the estimates of characteristics of the whole population. In stratified sampling, the population of N units is first divided into subpopulations (called strata) that are nonoverlapping and that together comprise the whole population. When the strata have been determined and a simple random sample is taken in each stratum, the whole procedure is described as stratified random sampling (Cochran, 1977).

The Itaboraí Youth study used a three‐stage sampling procedure that involved, first, a random sample of census units (107/420) using the method “probability proportional to the size,” second, a random sample of eligible households (15 in each selected census unit), and, third, a random selection of the target child among all eligible children in the household. Census units were defined by the last Brazilian national census (2010). In the selected census units (n = 107), all households were visited to identify eligible households (residence of a 6‐to‐15‐year old and his/her biological, adoptive, or step mother). The initial eligible sample included 1,605 mother–child pairs, and no one was replaced in case of refusal. Sampling weights were calculated based on the study three‐stage probabilistic sampling plan. Inclusion criteria for participation in the study were age 6 to 15 years, residing with his/her biological, adoptive, or step mother since the first year of life, and residing in Itaboraí city in the past 12 months or longer. Exclusion criteria were intellectual disabilities (child not able to play with other children or go to a regular school or regular classroom) and mother younger than 18 years.

In order to calculate sampling weights, specific information for each participant household was obtained: identification number of the census unit where the household was located, total number of eligible children in the household, and the value of “Fraction 1.” This value results from the division of the census unit size (number of households according to the last Brazilian census) by the total number of households in the city of Itaboraí according to the last census. The first weight was obtained when dividing “1” by Fraction 1. The second weight was obtained when dividing the total number of eligible households in the census unit where the household was located by the number of participating eligible households from the same census unit. The third weight was obtained when dividing the number of children aged 6–15 years in the household by “1” because only one eligible child was randomly selected per household. The final weight was obtained by multiplying these three weights (Weight 1 × Weight 2 × Weight 3). A standardized weight was obtained when dividing the final weight by 3,208,636 and multiplying the result by 1,409 with 3,208,636 being the sum of the final weight of the 107 selected census units and 1,409 being the sample size at the study baseline.

2.3. Data collection

All data were collected during face‐to‐face interviews in the household carried out by trained lay interviewers with at least a high‐school diploma. The interviews with mothers and adolescents were 60 to 90 min long, depending on positive answers to key items that opened a series of new items for gathering detailed information on the topic (e.g., types of service use and professional assistance due to violence exposure). Because interviewers had to use public transportation or walk to reach the selected households, they used paper and pencil for data collection instead of electronic devices to avoid being exposed to robbery and assault.

In each selected household, interviewers contacted the mother of the target child, explained her the content of the written informed consent, asked for her signature in that document, and applied the questionnaire in the household while making sure other residents were not listening. When the target child was an adolescent, the interviewer asked for the mother's consent to interview her son or daughter. After obtaining her signature on a written informed consent, the interviewer asked for the adolescent's assent. The adolescent's interview could occur in the same day of the mother's interview or a few days later. Adolescents answered the interviewer's questions in the household under privacy conditions, and his/her interview always occurred after the mother's interview was completed. When the mother completed the questionnaire but her adolescent son or daughter refused to participate in the study, this mother–adolescent pair was excluded from the sample.

Before starting Wave 1 data collection, questionnaires were applied to 200 mothers and 109 adolescents residing in nonselected census units from Itaboraí (pilot study) in order to test fieldwork procedures, comprehension of questionnaire items, and data entry procedures. The pilot study was useful to show that mothers were frequently working or involved in activities outside home at any day or time. Therefore, it was necessary to increase the number of home visits up to 10 per household (in different times and days of the week including weekends) in order to find mothers at home with time available to complete the questionnaire in the same day (60 to 90 continuous minutes). Furthermore, items that were difficult to understand had its wording simplified without distorting its content and were submitted to a new back‐translation. Final forms of questionnaires were then ready to the main study.

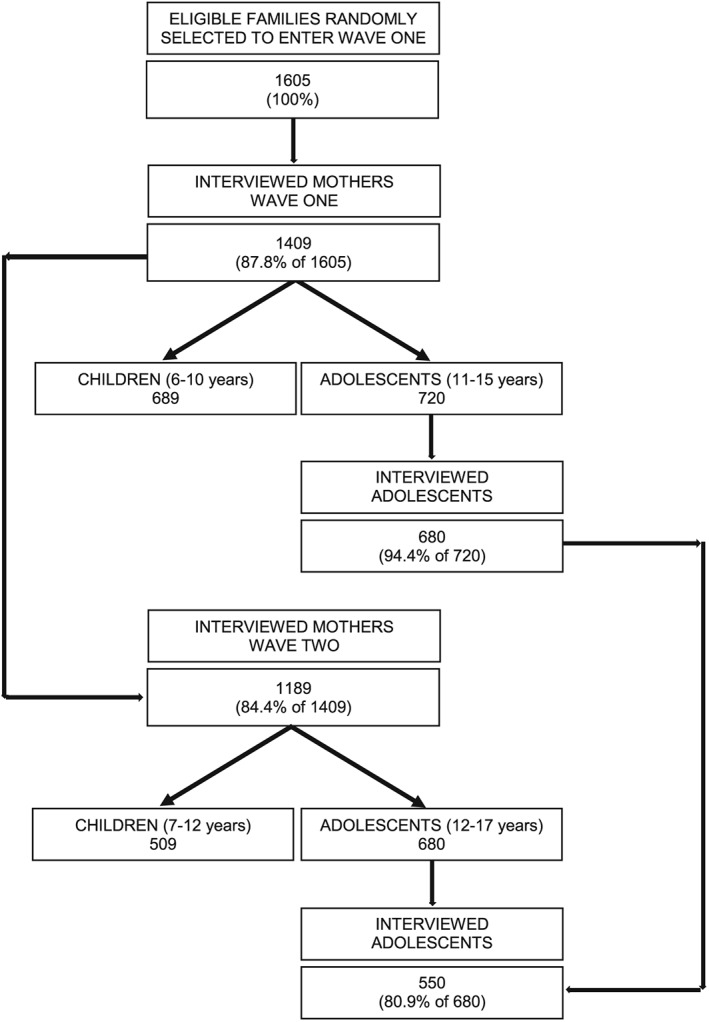

The Itaboraí Youth Study involved two periods of data collection with a mean interval of 12.9 months. From February to December 2014 (Wave 1), interviewers applied a semi‐structured questionnaire to biological, adoptive, or step mothers of the baseline sample of 6‐to‐15‐year olds (n = 1,409; response rate = 87.8%). In this baseline sample, 730 were boys, and 720 were adolescents (aged 11–15 years). In Wave 1, 680 adolescents were individually interviewed (response rate = 94.4%). In Wave 2, the study collected valid data from 1,189 mothers (response rate = 84.4%) and 550 adolescents (response rate = 80.9%; Figure 1). Field work supervisors checked all completed questionnaires and referred them to the data entry team. Waves 1 and 2 databases were cleaned by members of our research team who also translated all questionnaires' and databases' content to English in order to allow access to the entire international team of researchers.

Figure 1.

Itaboraí Youth Study: Participants and response rates

Because criminality rates had increased in Itaboraí city lately (Bruno & Pandeff, 2016), it was necessary to increase the number of home visits during Wave 2 in order to achieve higher compliance rates. The maximum number of 10 visits per household in different times and days of the week including weekends increased to 15 visits per household. In order to avoid the exposure of interviewers to assault or rape in more remote areas or more violent neighbourhoods, new field work procedures were adopted such as visiting households in pairs, not working after sunset, and using rented vans for transportation.

The data collection team included 20 interviewers that were selected based on their performance during a 3‐day training period. A member of our research team trained all interviewers. This training involved (a) receiving a detailed explanation of the project and structure of questionnaires' sections; (b) role‐playing activities in which interviewers applied questionnaires to one another while his/her partner pretended to be the interviewee (mother or adolescent); and (c) field work activities in which each interviewer applied 10 questionnaires to mothers and 10 questionnaires to adolescents, followed by group supervisions that discussed the most frequent doubts and difficulties and possible solutions. During the 2‐year period of data collection, four training workshops were necessary due to the admission of new interviewers into the team.

2.4. Study variables: Measures and instruments

All study variables were measured on the basis of mothers and/or adolescents' responses to interview questions. The study included a range of child and adolescent variables covering the following areas: demographics, mental health problems and impact, exposure to violence (at home, community, and/or school), exposure to sexual abuse, stressful life events, suicidality, PTSD symptoms, alcohol and drug consumption, parental styles, resilience, and service use. The great majority of topics was investigated based on both informants: mothers (information gathered on the entire sample) and adolescents (self‐reports for the age group 11–15 years). Maternal anxiety and/or depression, maternal victimization by severe marital violence, and alcohol and drug use by the mother and/or her husband or partner were also relevant factors investigated during the interview with mothers.

Items derived from questionnaires originally developed in English but with no official Brazilian version were translated to Brazilian Portuguese by two of the paper's authors (I. A. B. and W. S. R.) and back translated to English by a professional translator with English as his mother language. These items were pretested in focus groups involving typical low‐educated women and adolescents to identify items still in need of minor modifications. Final Brazilian versions of all standardized instruments were included in the questionnaires applied to mothers and adolescents. Translation procedures followed the norms proposed by Streiner and Norman (1995).

Measures described in Table 1 refer to specific child and adolescent variables (key constructs of the study), which prevalence rates at the study baseline are reported in this paper. Other variables measured by the study will be theme of future publications.

Table 1.

Child and adolescent's variables of interest for the study: Instruments applied to mothers and/or adolescents and definition of variables

|

Mother as informant |

Adolescent as informant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Instrument | Definition | Instrument | Definition |

| Exposure to violence at home | Brazilian version of the World Studies of Abuse in the Family Environment (WorldSAFE) Core Questionnaire (Bordin et al., 2009) | Any severe physical punishment by one or both parents in the past 12 months (at least one positive item from the 8 items listed in Table 2—possible answers for all items: “no” [0], “yes” [1]) | Brazilian version of the World Studies of Abuse in the Family Environment (WorldSAFE) Core Questionnaire (Bordin et al., 2009) | Any severe physical punishment by one or both parents in the past 12 months (at least one positive item from the 8 items listed in Table 2—possible answers for all items: “no” [0], “yes” [1]) |

| Exposure to violence at the community: Victimization events that occurred outside the school and home environments | Investigation of 8 topics (beatings and muggins, forced entry, being chased, arrests, threats, knife attacks, shootings, sexual molestation) selected from the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence—Self Report Version, developed at the National Institute of Mental Health by Richters and Saltzman (1990). Differently from the original Self Report Version, two separate items investigated beatings and muggins, and two new items were added by our research team (being around a shoot‐out and suffering death threats) | Any victimization by community violence in the past 12 months (at least one positive item from the 11 items listed in Table 2—possible answers for all items: “no” [0], “yes” [1]) | Investigation of 8 topics (beatings and muggins, forced entry, being chased, arrests, threats, knife attacks, shootings, sexual molestation) selected from the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence—Self Report Version, developed at the National Institute of Mental Health by Richters and Saltzman (1990). Differently from the original Self Report Version, two separate items investigated beatings and muggins, and two new items were added by our research team (being around a shoot‐out and suffering death threats) | Any victimization by community violence in the past 12 months (at least one positive item from the 11 items listed in Table 2—possible answers for all items: “no” [0], “yes” [1]) |

| Exposure to violence at the community: Eye‐witnessed events that occurred outside the school and home environments | None | None | Same topics and items related to the occurrence of eye‐witnessed real life events (media exposure excluded) | Any eye‐witnessed community violence in the past 12 months (at least one positive item from the 11 items listed in Table 2—possible answers for all items: “no” [0], “yes” [1]) |

| Exposure to violence at school | None | None | Arora's “My Life in School” (MLS) checklist (Arora, 1994; Arora & Thompson, 1987). Selected and modified items previously used in a Norwegian study with schoolchildren (Rønning, Handegaard, & Sourander, 2004) | Three types of peer harassment events (any event occurring more than once in the past 6 months): physical aggression (4 items), verbal harassment (5 items), and social manipulation (6 items). Any peer harassment corresponds to at least one event occurring more than once from the 15 items listed in Table 3—possible answers for all items: “not at all” (0), “once” (1), “more than once” (2) |

| Mother‐perceived bullying victimization at school | One question developed by the authors: “Was the child threatened, maltreated, or chased by peers at school?” | A yes response identifies victimization by school violence in the past 12 months | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Self‐perceived bullying victimization at school | Not applicable | Not applicable | After defining bullying (when one or more school peers are repeatedly doing bad things to you such as name‐calling, threatening, hitting, spreading rumours about you, excluding you from the group, or teasing you to hurt your feelings), one question developed by the authors was asked: “How often have you been bullied in the past 6 months?” | Possible answers for this question: “not at all” (0), “less than once a week” (1), “more than once a week” (2), “almost every day” (3). Self‐perceived bullying victimization in the past 6 months corresponds to an answer of more than once a week or almost every day |

| Mental health clinical problems based on SDQ | Brazilian version of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for parents of 4‐ to 17‐year olds (Fleitlich‐Bilyk, 2002) | SDQ scale scores in the clinical range according to pre‐established cut‐off points based on normative data from large population‐based studies conducted in the United Kingdom (details at http://www.sdqinfo.com) | Brazilian version of the self‐rated SDQ for 11 to 17‐year olds (Fleitlich‐Bilyk, 2002) | SDQ scale scores in the clinical range according to pre‐established cut‐off points based on normative data from large population‐based studies conducted in the United Kingdom (details at http://www.sdqinfo.com) |

| Mental health clinical problems based on Achenbach's instruments | Braziian version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Bordin et al., 2013) | CBCL scale T‐scores in the clinical range according to pre‐established cut‐off points based on normative data from the United States (Bordin et al., 2013) | Brazilian version of the Youth Self‐Report (YSR/11–18) (Bordin et al., 2013) | YSR scale T‐scores in the clinical range according to pre‐established cut‐off points based on normative data from the United States (Bordin et al., 2013) |

| Symptoms of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | None | None | 20 DSM IV PTSD symptoms (listed in Table 4), and one impairment item were investigated by the corresponding items from the Brazilian version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School‐Age Children/ Present and Lifetime Version (K‐SADS‐PL) (Brasil & Bordin, 2010). | PTSD symptoms were investigated only when the adolescent identified one traumatic event currently most bothersome among all previously reported violence exposure events and/or stressful life events occurred in the past 12 months. Possible answers for all items: “no” (0), “yes” (1). The authors of the current paper determined that adolescents with three or more PTSD symptoms and impairment were those more severely affected by the traumatic event |

2.5. Ethical considerations

The Brazil's National Committee for Ethics in Research (process Number 25000.182992/2011–76) and the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (process Number 0324/11) approved the study. A written informed consent was obtained from all participant mothers and a written informed assent from all participant adolescents. Each participant household received a unique code to be used in the questionnaires and databases to guarantee anonymity of participants' identity.

As soon as information from study participants were available in partial databases, subjects in need of urgent mental health attention were identified and referred to local health centres. Children and adolescents in need of urgent mental health attention were those who attempted suicide, suffered severe physical punishment by parents, were victims of sexual abuse, had serious problems due to use of alcohol or drugs, and/or were impaired by the presence of three or more PTSD symptoms. Parents in need of attention were those who had serious problems due to use of alcohol or drugs, and mothers who attempted suicide or were victims of severe physical marital violence. Mothers received a formal written referral signed by the study principal investigator in Brazil and could decide to use it or not to make an appointed at the nearest health centre.

2.6. Statistical analysis

In this paper, absolute numbers of subjects are unweighted (refer to the sample) but all percentages are weighted because sampling weights were applied to generate prevalence rates among the population of same‐age children and adolescents that live in Itaboraí city. The sampling plan was taken into account when obtaining means and when performing Chi‐square tests to verify differences in prevalence rates between children and adolescents with mothers being the informant for both age groups (independent samples). In order to identify differences in prevalence rates among adolescents according to the informant (mothers' reports and self‐reports), McNemar's tests were performed on paired proportions using weighted data. SPSS 24 was used for all analyses.

3. RESULTS

The study baseline sample included 1,409 children aged 6 to 15 years, 730 (52.5%) being boys and 679 (47.5%) being girls. The total sample included 689 (48.7%) children (6–10 years) and 720 (51.3%) adolescents (11–15 years). The total sample mean age was 10.6 ± 0.1 years.

All adult informants were female and included biological mothers (94.6%), adoptive or step mothers (0.6%) and substitutes of absent mothers (intrafamily adoption: 4.8%). The grandmother was the most frequent mother substitute (4.1% of all informants). The age of mothers or substitutes ranged from 19 to 77 years (mean ± SD: 36.2 ± 0.4 years), 47.4% of them did not complete 8 years of schooling, and 48.8% were not working for pay in the last 30 days.

The majority (70.5%) of mothers or substitutes had a husband or partner residing in the household. Among women without a husband or partner (n = 430), 69.8% were separated, 14.7% were widowed, and 13.7% never cohabitated with a husband or partner. When considering all households with a resident husband or partner (n = 979), most of them (67.1%) were the child's biological father, 27.6% were stepfathers, 0.9% were adoptive fathers, and 4.4% were grandfathers or uncles (intrafamily adoption). The husband or partner's age ranged from 18 to 81 years (mean ± SD: 39.5 ± 0.5 years), 45.6% of them did not complete 8 years of schooling, and 9.0% were not working for pay in the last 30 days.

At the study baseline, 680 adolescents (11–15 years) with a mean age of 13.0 ± 0.1 years were interviewed, 332 (48.1%) being boys and 348 (51.9%) being girls. Based on adolescent's report, 669 (98.4%) were in school in the past 6 months and therefore, could answer questions about school violence.

Basic findings from Wave 1 are presented below involving the prevalence of violence exposure, mental health problems, and symptoms of PTSD. Mother reported prevalence rates were compared considering two age groups: children (6–10 years) versus adolescents (11–15 years; Tables 2 and 4). Mother and adolescent reported prevalence rates were compared considering the age group 11–15 years (Tables 2 and 4).

Table 2.

Child and adolescent violence exposure at home and in the community reported by mothers and by adolescents

| Informant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Mothers | Adolescents | |

| (Age 6–10) | (Age 11–15) | (Age 11–15) | |

| n = 689 | n = 720 | n = 680 | |

| Child and adolescent violence exposure events | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Severe physical punishment (eventsa occurring at least once in the past 12 months) | |||

| Being hit with an object (e.g., stick, broom, cane, belt) | 54 (8.0) | 72 (9.7) | 61 (10.0) |

| Being kicked | 3 (0.5) | 7 (0.7) | 8 (1.7) |

| Being choked by putting hands (or something else) around his/her neck | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.8) |

| Being smothered with hand of pillow | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Being burned, scalded, or branded | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Being beaten | 18 (2.9) | 28 (4.3) | 34 (5.9) |

| Being threatened with a knife or gun | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Being harmed with a knife or gun | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any event occurring at least once in the past 12 months | 63 (9.7) | 79 (11.0) | 80 (13.0) |

| Community violence (eventsb occurring at least once in the past 12 months) | |||

| Victimization events | |||

| Being mugged | 3 (0.4) | 14 (1.5)* | 14 (2.2) |

| Someone has broken into or tried to force their way into the house or apartment when he/she was there | 6 (1.3) | 7 (0.8) | 17 (2.9)## |

| Being chased by gangs or individuals | 4 (0.9) | 6 (0.5) | 12 (1.5) |

| Being picked‐up or arrested by the police or taken to the police station | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.6) |

| Being threatened by someone with serious physical harm | 4 (0.5) | 11 (1.5) | 23 (3.8)## |

| Suffering death threats | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 6 (0.7) |

| Being beaten‐up | 3 (0.4) | 9 (1.5) | 17 (2.8)## |

| Being attacked or stabbed with a knife | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.9) |

| Being around a shoot‐out | 25 (3.7)* | 17 (1.6) | 44 (6.3)### |

| Being shot | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Being sexually molested by someone much older than him/her | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| One or more events occurring at least once in the past 12 months | 39 (6.4) | 54 (6.2) | 97 (14.2)### |

| Eye‐witnessed events | |||

| Being mugged | 44 (6.5) | ||

| Someone has broken into or tried to force their way into the house or apartment when he/she was there | 12 (1.7) | ||

| Being chased by gangs or individuals | 20 (2.4) | ||

| Being picked‐up or arrested by the police or taken to the police station | 73 (9.4) | ||

| Being threatened by someone with serious physical harm | 59 (7.9) | ||

| Suffering death threats | 19 (2.8) | ||

| Being beaten‐up | 77 (11.2) | ||

| Being attacked or stabbed with a knife | 11 (1.5) | ||

| Being around a shoot‐out | 43 (5.1) | ||

| Being shot | 24 (2.8) | ||

| Being sexually molested by someone much older than him/her | 17 (1.9) | ||

| One or more events occurring at least once in the past 12 months | 160 (21.1) | ||

Note. Empty cells refer to items not included in the mothers' questionnaire to avoid inaccurate answers.

Severe physical punishment by one or both parents.

Events that occurred outside home or school.

Chi‐square tests performed to identify differences between children rates and adolescent rates (all mother reported).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

McNemar's tests performed to identify differences between paired proportions in the age group 11–15 years (mother reported rates vs. adolescent reported rates).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Table 4.

Child and adolescent mental health problems in the clinical level a reported by mothers and by adolescents and current post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms reported by adolescents

| Child/adolescent mental health | Informant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Mothers | Adolescents | |

| (age 6–10) | (age 11–15) | (age 11–15) | |

| n = 689 | n = 720 | n = 680 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Clinical mental health problems (past 6 months)a | |||

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | SDQ‐parent | SDQ‐parent | SDQ‐youth |

| Emotional problems | 126 (18.5) | 172 (24.4)*, ### | 71 (11.4) |

| Conduct problems | 160 (24.1) | 153 (25.4) ### | 93 (13.8) |

| Hyperactivity‐inattention | 147 (22.8) | 122 (18.9) ### | 77 (9.9) |

| Peer problems | 142 (22.9) | 161 (23.5) ### | 49 (6.7) |

| Total problems | 129 (21.4) | 135 (20.9) ### | 86 (12.8) |

| Child Behaviour Checklistb/Youth Self‐Report | CBCL | CBCL | YSR |

| Anxious/depressed | 39 (6.9) | 46 (7.8) | 39 (6.5) |

| Withdrawn/depressed | 21 (4.5) | 40 (5.6) | 21 (3.9) |

| Somatic complaints | 24 (4.3) | 39 (5.7)## | 17 (3.1) |

| Social problems | 17 (4.4) | 14 (2.2) | 24 (4.1) |

| Thought problems | 19 (3.1) | 13 (2.9)### | 4 (0.8) |

| Attention problems | 30 (4.5) | 27 (4.5) | 35 (5.3) |

| Rule‐breaking | 18 (3.6) | 12 (2.3)### | 1 (0.2) |

| Aggressive behaviour | 48 (8.3) | 55 (8.1) | 36 (6.0) |

| Internalizing problems | 93 (15.4) | 126 (17.8)### | 69 (11.5) |

| Externalizing problems | 87 (14.9) | 94 (13.7)### | 55 (8.4) |

| Total problems | 79 (13.4) | 100 (15.4)### | 60 (9.8) |

| Current PTSD symptomsc | |||

| Recurrent thoughts or images of event | 26 (4.6) | ||

| Avoidance of thoughts or feelings | 27 (4.9) | ||

| Nightmares | 8 (1.8) | ||

| Insomnia | 11 (1.8) | ||

| Irritability, outburst of anger | 10 (1.9) | ||

| Repetitive play | 6 (1.2) | ||

| Dissociative episodes | 12 (1.9) | ||

| Illusions | 8 (1.3) | ||

| Hallucinations | 7 (0.8) | ||

| Distress elicited from exposure to stimuli that resemble or symbolize event | 19 (3.5) | ||

| Avoidance of activities | 26 (4.8) | ||

| Inability to recall | 12 (2.1) | ||

| Diminished interest in activities | 6 (0.7) | ||

| Feelings of detachment | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Restricted affect | 3 (0.5) | ||

| Sense of foreshortened future | 4 (0.7) | ||

| Difficulty concentrating | 15 (3.1) | ||

| Hypervigilance | 16 (2.8) | ||

| Exaggerated startle response | 13 (2.1) | ||

| Physiologic reactivity upon exposure to events that symbolize traumatic event | 10 (2.0) | ||

| Three or more current PTSD symptoms | 31 (5.4) |

Note. Empty cells refer to items not included in the mothers' questionnaire. PTSD = post‐traumatic stress disorder.

Scores in the clinical range according to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Achenbach's instruments.

One missing subject.

Related to the currently most bothersome traumatic event among all previously reported violence exposure events (at home, school or community) and/or stressful life events occurred in the past 12 months.

Chi‐square tests performed to identify differences between children rates and adolescent rates (all mother reported).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

McNemar's tests performed to identify differences between paired proportions in the age group 11–15 years (mother reported rates vs. adolescent reported rates).

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

3.1. Violence exposure (at home, community, and school)

According to mothers' report, in the past 12 months, 9.7% of children and 11.0% of adolescents were severely punished by one or both parents with being hit with an object as the most frequent event in both age groups. Self‐reports of adolescents also indicated a high rate of severe physical punishment (13.0%) with the predominance of being hit with an object (Table 2).

Regarding victimization by one or more community violence events in the past 12 months based on mothers' report, similar prevalence rates were noted among children and adolescents (6.4% vs. 6.2%). However, in the age group 11–15 years, adolescents reported higher rates than mothers for being exposed to one or more events in the past 12 months (14.2% vs. 6.2%, p < .001). According to adolescents' report, the prevalence of eye‐witnessing one or more community violence events was even greater than being victimized by one or more community violence events, with seeing someone being beaten‐up and being arrested by the police as the most frequent events (Table 2).

In mothers' opinion, similar proportions of children and adolescents were threatened, maltreated, or chased by peers at school in the past 12 months (7.7% and 10.0%, respectively). According to in‐school adolescents (n = 669), 21.9% were exposed to at least one school violence event that occurred more than once in the past 6 months. Among these events, verbal harassment was more frequent than social manipulation that was more frequent than physical aggression. Table 3 shows the frequency of all school violence events investigated.

Table 3.

Adolescent exposure to school violence events and self‐perceived bullying victimization reported by in‐school adolescents (n = 669)

| Adolescent violence exposure events |

Adolescents In school (Age 11–15) n (%) |

|---|---|

| School violence (events occurring more than once in the past 6 months) | |

| Physical aggression | |

| Another pupil has tried to kick him/her | 28 (4.7) |

| Another pupil has threatened him/her | 9 (1.9) |

| Another pupil has tried to trip him/her up | 19 (3.2) |

| Another pupil has tried to hit him/her | 16 (3.2) |

| Any physical aggression (events occurring more than once in the past 6 months) | 46 (8.7) |

| Verbal harassment | |

| Another pupil has called him/her names | 63 (11.1) |

| Another pupil has teased him/her | 68 (10.1) |

| Another pupil has teased him/her about his/her family | 7 (1.5) |

| Another pupil has teased him/her because he/she was different | 17 (2.0) |

| Another pupil has tried to hurt his/her feelings | 27 (3.8) |

| Any verbal harassment (events occurring more than once in the past 6 months) | 111 (17.6) |

| Social manipulation | |

| Another pupil has ganged up on him/her | 3 (0.3) |

| Another pupil has tried to make him/her hurt other people | 17 (2.4) |

| Another pupil has tried to get him/her into trouble | 26 (3.9) |

| Another pupil has made him/her do something he/she didn't want to | 6 (0.5) |

| Another pupil has threatened to tell on him/her | 25 (3.5) |

| Another pupil has told a lie about him/her | 37 (7.1) |

| Any social manipulation (events occurring more than once in the past 6 months) | 71 (11.3) |

| Any school violence (events occurring more than once in the past 6 months) | 141 (21.9) |

| Self‐perceived bullying victimization (more than once a week in the past 6 months) | 37 (5.5) |

3.2. Mental health

According to mother's report on the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), prevalence rates of total problems in the clinical range were similar among children (21.4%) and adolescents (20.9%). However, adolescents had a higher rate of emotional problems compared to children. In the age group 11–15 years, mothers reported higher rates than adolescents for all SDQ problem scales (Table 4).

When considering child behaviour checklist (CBCL) results for children and adolescents, similar rates were noted in the two age groups for narrow‐band and broad‐band scales. When comparing CBCL and youth self‐report (YSR) results for the age group 11–15 years, mothers reported higher rates than adolescents for somatic complaints, thought problems, rule‐breaking behaviour, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and total problems (Table 4).

When comparing the prevalence rates of total problems in the clinical range according to different screening instruments, mother‐reported SDQ generated a higher rate than CBCL, and adolescent‐reported SDQ generated a higher rate than YSR (Table 4).

3.3. PTSD symptoms

Adolescents also informed about PTSD symptoms related to the currently most bothersome traumatic event among all reported violence exposure events and/or stressful life events, with 5.4% of them presenting three or more symptoms. The most frequent PTSD symptoms were avoidance of thoughts or feelings related to the event, avoidance of activities that reminded the event, and recurrent thoughts or images of the traumatic event (Table 4).

3.4. Overall prevalence

When observing prevalence rates of selected child and adolescent variables in the age group 6–15 years (n = 1,409) based on mother's report, it was clear that the studied population was exposed to relevant levels of violence and clinical mental health problems (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence rates of selected child and adolescent variables for the age group 6–15 years (n = 1,409) based on mother's report

| Child and adolescent variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Violence exposure | |

| Severe physical punishmenta (events occurring at least once in the past 12 months) | |

| Any event occurring at least once in the past 12 months | 142 (10.4) |

| Community violenceb (events occurring at least once in the past 12 months) | |

| One or more victimization events | 93 (6.3) |

| Mother‐perceived bullying victimizationc (past 12 months) | 118 (8.9) |

| Clinical mental health problems (past 6 months) | |

| Strengths and difficulties questionnaire | |

| Emotional problems | 298 (21.6) |

| Conduct problems | 313 (24.8) |

| Hyperactivity‐inattention | 269 (20.8) |

| Peer problems | 303 (23.2) |

| Total problems | 264 (21.2) |

| Child Behaviour Checklistd | |

| Anxious/depressed | 85 (7.4) |

| Withdrawn/depressed | 61 (5.0) |

| Somatic complaints | 63 (5.0) |

| Social problems | 31 (3.3) |

| Thought problems | 32 (3.0) |

| Attention problems | 57 (4.5) |

| Rule‐breaking | 30 (2.9) |

| Aggressive behavior | 103 (8.2) |

| Internalizing problems | 219 (16.6) |

| Externalizing problems | 181 (14.3) |

| Total problems | 179 (14.4) |

Severe physical punishment by one or both parents.

Events that occurred outside home or school.

Investigated by one question: “Was the target child threatened, maltreated or chased by peers at school?”

One missing subject.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Considerations about the study design and methods

Studies examining the impact of different forms of violence exposure on child and adolescent mental health in low resource and violent urban settings are very scarce. In Brazil, the current study is the first to evaluate a population‐based sample of children and adolescents in order to examine the influence of different types of violence exposure (at home, community, and school) and stressful life events on their mental health (theme of future publications). The study strengths include a longitudinal design, a probabilistic sample of children from a low‐income medium‐size city, a high response rate, the use of standardized instruments, data collection from two informants (mother and adolescent), subjects individually submitted to face‐to‐face interviews instead of self‐completing questionnaires (to avoid errors due to the high frequency of low‐educated respondents), and information gathered on a variety of potential predictors and protective factors. In addition, because the study site is characterized by adverse conditions (low parental education, high proportion of mothers not working for pay, lack of a father figure in the home, and high exposure of children to violence), study results are expected to be valid to vulnerable children living under similar circumstances in other Brazilian cities and abroad. Therefore, authors of this paper expect that their research methods could be applicable in deprived and violent regions worldwide, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Study limitations should also be mentioned such as the lack of a third wave of data collection that would allow the observation of long‐term effects of violence exposure on child mental health. When planning the study, the research team decided for an interval of 12 months between Waves 1 and 2 assessments in order to minimize sample loss because residential mobility is high among low‐income Brazilian populations (Romanelli & Abiko, 2011). Furthermore, regarding the instruments used in our study to assess child mental health problems, potential criticisms involve the absence of child mental health measures based on diagnostic instruments. However, a recent publication (Boyle et al., 2016) mentions that the use of checklists are comparable to the use of diagnostic interviews when aiming to identify mentally disordered children in community samples from epidemiological studies. In addition, the use of checklists has the advantage of dramatically lowering the burden and cost of data collection (Boyle et al., 2016) which increases the feasibility of large epidemiological studies, mainly in low‐ and middle‐income countries where financial resources for scientific research are scarcer. Finally, the use of cut‐off points for SDQ, CBCL, and YSR on the basis of normative data from countries where the instruments were originally developed may limit the comparison of our findings with prevalence rates obtained by studies that used different cut‐offs. It is worthwhile to mention that previous population‐based studies conducted in Brazil that used SDQ also followed the recommendation of Robert Goodman (author of the original SDQ) to use the same cut‐offs adopted in the United Kingdom.

Another challenge to epidemiological studies conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries is the use of appropriate standardized instruments to identify clinical mental health problems in children and to determine their exposure to violence in multiple environments. According to Brandt, Ward, Dawes, and Flisher (2005), great care should be taken in adapting an instrument for use in a context in which it was not developed. Besides checking translations by back‐translations, researchers should take into account the respondents' developmental age and the need of piloting to examine whether the items are understood by the respondents in the way in which the researcher intends them to be understood (Brandt et al., 2005). The most frequently used instruments are valid and reliable but usually developed in high‐income countries, where the population has greater access to quality education. When developing our study questionnaires, it was fundamental to conduct focus groups to identify difficulties in comprehending certain items among low‐educated subjects. We simplified the wording of these items to facilitate respondents' understanding without distorting items' content. In addition, cultural aspects should be considered when adapting questionnaires to other societies (Brandt et al., 2005; Streiner & Norman, 1995). For instance, push‐ups are forms of corporal punishment used in the USA but not in many other countries, whereas hitting the head with knuckles are punishments used in India, Egypt, and Brazil but not in the USA (Runyan et al., 2010). Another example concerns the scale to evaluate exposure to community violence. Our research team included two new items in the questionnaire section that investigated community violence in order to capture local forms of violence exposure: being around a shoot‐out and suffering death threats. These items represent frequent events in low‐income violent Brazilian communities. From January 1 to July 2, 2017, 632 people were hit by stray bullets during crossfire events between police and drug trafficking groups in Rio de Janeiro State (O Globo, July 7th, 2017). In 2007, the Brazilian federal government created the Programme for the Protection of Children Threatened from Death. Until September 2016, the programme have protected 3,512 children and adolescents. The programme clientele is mainly constituted by black adolescents and youth aged 15–17 years. At the federal level, threats are mainly due to involvement with trafficking and come from organized crime and police officers (Agência Pública, May 23rd, 2017).

4.2. Prevalence

4.2.1. Violence exposure (at home, community, and school)

Child physical abuse is a widespread, global phenomenon affecting the lives of millions of children all over the world. A meta‐analysis including 111 studies with 9,698,801 participants found a vast variation of self‐reported prevalence rates in individual studies (Stoltenborgh, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, IJzendoorn, & Alink, 2013). The highest prevalence rates were found for studies using a broad definition of child physical abuse, studies measuring physical abuse over the longest period of 0–18 years, studies in which adults served as respondents, and studies using more questions on physical abuse. The authors concluded that more cross‐cultural research on physical abuse is badly needed, especially in Africa and South America. In our study, 10.4% of children aged 6–15 years suffered severe physical punishment by parents in the past 12 months according to mothers' report. The same instrument, variable definition, time frame, and mother as informant were adopted in a previous multi‐country study (Runyan et al., 2010) involving probabilistic population‐based samples of subjects under 18 years of age from Brazil, Chile, Egypt, India, Philippines, and United States. Prevalence rates of severe physical punishment (including hitting with an object) in 19 communities from these six countries varied widely: 13–74% among children (7–11 years) and 7–72% among adolescents (12–17 years). One possible reason to explain this variation is the fact that these communities differed in living conditions including low income, middle class, urban, rural, and slum populations. In addition, when analyzing Brazilian data from this multi‐country study, Bordin et al. (2009) reported that 20.0% of children aged 6–17 years living in an urban‐poor neighbourhood of Embu, a city near São Paulo city, suffered severe physical punishment by one or both parents in the last 12 months. This rate was much greater than the rate observed in the current study (10.4%) probably because Embu was considered one of the most violent cities in the country at the time of data collection.

When reviewing the literature on the prevalence of community violence among American youth, Stein, Jaycox, Kataoka, Rhodes, and Vestal (2003) found that the majority of articles used convenient samples of children living in high‐risk situations, resulting in a preponderance of studies of urban and minority children. The authors highlight the need to investigate community violence in the general population to gain a better understanding of how exposure affects children in different circumstances. In our study, 14.2% of adolescents reported being victimized by at least one event of community violence in the past 12 months, a much lower rate compared to eye‐witnessing one or more events in the same period of time (21.1%). Our results are in accordance with the observation made by Stein et al. (2003) regarding prevalence estimates of physical and crime‐related community violence exposure with victimization rates being generally lower than witnessing rates.

In our study, 5.5% of adolescents reported bullying victimization (more than once a week or almost every day) in the past 6 months. This prevalence rate of self‐perceived bullying victimization is compatible with the self‐reported rate of bullying victimization (almost always or always) in the last 30 days (5.4%; 95% CI: [5.1%, 5.7%]) obtained by a cross‐sectional study involving 60,973 Grade 9 students from public and private schools from all 26 Brazilian state capitals and the Federal District (Malta et al., 2010). The authors investigated bullying victimization with a question: “In the past 30 days, how often did any of your school colleagues embarrassed, mocked, made fun of, intimidate or tease you so much that made you feel hurt, upset, annoyed, offended or humiliated?” Because prevalence rates were similar despite differences in the time interval, it is reasonable to hypothesize that bullying victimization is a chronic condition that maintains its frequency month after month.

4.2.2. Mental health

When comparing prevalence rates of mental health problems among children and adolescents reported by different studies, it is important to be aware that rates may vary depending on the rigor of methods applied, proportion of sample loss, specific instruments used among the screening questionnaires and diagnostic interviews available in the local language, definition of variables, adopted time frames, type of informant (e.g., parent, youth, and teacher), age range of subjects among other. It is important to highlight that prevalence rates of mental health problems on the basis of screening questionnaires are usually higher than rates generated by diagnostic instruments because psychiatric diagnoses require the presence of impairment (Murray, Anselmi, Gallo, Fleitlich‐Bilyk, & Bordin, 2013). For instance, in a probabilistic sample of low‐income children (6–17 years) from southeast Brazil (n = 479), the prevalence of total problems in the clinical range according to CBCL and/or YSR was 24.6%, but this rate decreased to 7.3% when impairment was required (Paula, Duarte, & Bordin, 2007).

According to a literature review on population‐based studies (Bordin & Paula, 2007), prevalence rates of mental health problems in Brazilian children and adolescents derived from the use of screening instruments (e.g., SDQ and CBCL) vary according to the type of informant. In this review, prevalence of total problems varied from 13.5% to 35.2% based on parent reports, from 12.6% to 13.1% based on adolescent self‐reports, and from 8.3% to 10.3% based on teacher reports (Bordin, Curto, & Paula, 2010; Bordin & Paula, 2007). Prevalence rates of total problems reported in this paper (Tables 4 and 5) are compatible with these intervals.

When reviewing evidence on the prevalence of conduct problems in Brazil, Murray et al. (2013) found an average prevalence of 20.8% (95% CI: 15.9%, 26.9%) for conduct problems when using screening questionnaires. Again, prevalence rates of conduct problems reported in this paper (Tables 4 and 5) are compatible with this interval. Our findings are also in agreement with the fact that parents report higher rates compared to adolescent self‐reports (Murray et al., 2013).

5. CONCLUSION

Prevalence rates presented here estimate the true extent of violence exposure and child mental health problems in a Brazilian low‐income medium‐size city. Estimates are probably valid to other Brazilian low‐income medium‐size cities due to similarities in terms of precarious living conditions. When checking an external validity criterion for the population representativeness of our sample, we found similarities between the rate of maternal low education estimated by our study (47.4%) and the rate reported by the last Brazilian census (IBGE, 2010c) in the female population of Itaboraí city older than 24 years of age (50.8%). The dissemination of data gathered is fundamental to inform planning and action at the local level. Finally, the authors of this paper expect that the study methods described could be useful to future studies conducted in Brazil and in other world regions where children living in poor and adverse environments are suffering from violence and mental health problems.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This research received financial support from the Research Council of Norway (Project: 201470/H30).

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to the current article. I. A. B., C. S. D., A. S., and J. A. R. were involved in study conception and definition of study objectives. All authors contributed with the development of questionnaires, selection of variables and measures, interpretation of data, revision of the final draft critically for important intellectual content, and have given final approval of the version to be published. C. S. D. and A. S. were also involved in acquisition of funds. I. A. S. and W. S. R. were also involved in the translation of instruments from English to Brazilian Portuguese and translation of questionnaire packages from Brazilian Portuguese to English. W. S. R. was also involved in the coordination of fieldwork and training of interviewers. I. A. B. was also involved in data cleaning, translation of databases to English, and drafting the manuscript. All authors take public responsibility for the paper's content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study research team is grateful to the Research Council of Norway (RCN) for the financial support received (Project 201470/H30; RCN, 2010). They also thank the administrative staff of Universidade Federal de São Paulo for their constant assistance, and the staff from the Brazilian Institute of Public Opinion and Statistics (IBOPE) for the careful work of data collection and data entry completed. Our gratitude also goes to scientific authorities from University of Trømso (Norway) and Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Brazil), municipality, and health authorities from Itaboraí city and study participants.

Bordin IA, Duarte CS, Ribeiro WS, et al. Violence and child mental health in Brazil: The Itaboraí Youth Study methods and findings. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27:e1605 10.1002/mpr.1605

REFERENCES

- Agência Pública . (May 23rd 2017). Direitos humanos: Jurados pela polícia e pelo tráfico [Human rights: Sworn to death by police and drug trafficking]. Retrieved from https://apublica.org/2017/05/jurados-pela-policia-e-pelo-trafico/

- Alves, R. C. O. L. (2016). Cidades médias: Um ensaio teórico sobre gestão da qualidade de vida urbana e suas dimensões. Cadernos de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, 21, 99–112. Retrieved from http://periodicos.uesb.br/index.php/cadernosdeciencias/issue/view/258/showToc [Google Scholar]

- Arora, C. M. J. , & Thompson, D. A. (1987). Defining bullying for a secondary school. Educational and Child Psychology, 4(3), 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, T. (1994). Measuring bullying with the “Life in School” checklist. Pastoral Care in Education, 12(3), 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, S. G. , Avanci, J. Q. , Pesce, R. P. , & Ximenes, L. F. (2009). Situação de crianças e adolescentes brasileiros em relação à saúde mental e à violência [The situation of Brazilian children and adolescents with regard to mental health and violence]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 14(2), 349–361 discussion 362‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanci, J. , Assis, S. , Oliveira, R. , & Pires, T. (2009). Quando a convivência com a violência aproxima a criança do comportamento depressivo [When living with violence brings a child close to depressive Behavior]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 14(2), 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanci, J. Q. , Assis, S. G. , & Pesce, R. P. (2008). Depressão em crianças: Uma reflexão sobre crescer em meio à violência In Depressão em crianças: Uma reflexão sobre crescer em meio à violência (pp. 77). Rio de Janeiro: FIOCRUZ/ENSP/CLAVES/CNPq. [Google Scholar]

- Blount J. (2015) As Petrobras scandal spreads, economic toll mounts for Brazil. http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/20/us-brazil-petrobras-impact-idUSKBN0NB1QD20150420

- Bordin, I. A. , Curto, B. , & Paula, C. S. (2010). Mental health problems, violence and other environmental risk factors among disadvantaged Brazilian children and adolescents In Lovisi G. M., Mari J. J., & Valencia E. (Eds.), (Org.) Psychological impact of living under violence and poverty in Brazil (pp. 43–60). New York: Nova science pub Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bordin, I. A. , Duarte, C. S. , Peres, C. A. , Nascimento, R. , Curto, B. M. , & Paula, C. S. (2009). Severe physical punishment: Risk of mental health problems for poor urban children in Brazil. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(5), 336–344. 10.2471/BLT.07.043125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordin, I. A. , & Paula, C. S. (2007). Estudos populacionais sobre saúde mental de crianças e adolescentes brasileiros In Mello M. F., Mello A. A. F., & Kohn R. (Eds.), Epidemiologia da saúde mental no Brasil (pp. 101–117). São Paulo, SP: Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Bordin, I. A. , Rocha, M. M. , Paula, C. S. , Teixeira, M. C. T. , Achenbach, T. M. , Rescorla, L. A. , & Silvares, E. F. (2013). Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self‐Report (YSR) and Teacher's Report Form (TRF): An overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29(1), 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M. H. , Duncan, L. , Georgiades, K. , Bennett, K. , Gonzalez, A. , Van Lieshout, R. J. , … Lipman, E. L. (2016). Classifying child and adolescent psychiatric disorder by problem checklists and standardized interviews. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26, 1–9. 10.1002/mpr.1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R. , Ward, C. L. , Dawes, A. , & Flisher, A. J. (2005). Epidemiological measurement of children's and adolescents' exposure to community violence: Working with the current state of the science. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(4), 327–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, H. H. , & Bordin, I. A. (2010). Convergent validity of K‐SADS‐PL by comparison with CBCL in a Portuguese speaking outpatient population. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F. A. , & Pandeff, P. A. (2016). Análise das influências do COMPERJ no aumento da criminalidade em Itaboraí/RJ a partir dos processos distribuídos no Juizado Especial Criminal (JECRIM). Revista Científica da FACERB, 3(1), 23–40 Retrieved from http://www.cnecrj.com.br/ojs/index.php/ampliando/article/viewFile/254/168 [Google Scholar]

- Butchart, A. , & Mikton, C. (2014). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO press; ISBN 978 92 4 156479 3 Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/Reports/UNDP-GVA-violence-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cardia, N. (1999). Pesquisa sobre atitudes, normas culturais e valores em relação à violência em 10 capitais brasileiras. Brasília: Ministério da Justiça, Secretaria de Estado dos Direitos Humanos. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2015). Towards a violence free generation: Using science to fuel action and end violence against children. Atlanta: CDC; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/vacs/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A. L. (2013). Breve discussão sobre o conceito de cidade média [Brief discussion on the concept of médium‐sized cities]. Geoingá: Revista do Programa de Pós‐Graduação em Geografia, 5(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, E. (2003). Exclusão social e crescimento das cidades médias brasileiras. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fleitlich‐Bilyk, B. , & Goodman, R. (2004). Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleitlich‐Bilyk, B. W. (2002). The Prevalence of psychiatric problems in 7–14‐year olds in the Southeast of Brazil [thesis]. London: Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Institute of Psychiatry. King's College. London University. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis, S. , Mercy, J. , Amobi, A. , & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past‐year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), 1–13. 10.1542/peds.2015-4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) . (2010a) Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010 por Estado e Município: População Residente. Retrieved from http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br/sinopse/index.php?uf=33&dados=1

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) . (2010b) Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010 por Estado e Município: População por Grupo de Idade. Retrieved from http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br/sinopse/index.php?uf=33&dados=26

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) . (2010c) Censo Demográfico 2010: Educação e deslocamento – municípios – tabelas. Retrieved from https://ww2.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/educacao_e_deslocamento/default_mu_xls.shtm

- Kieling, C. , Baker‐Henningham, H. , Belfer, M. , Conti, G. , Ertem, I. , Omigbodun, O. , … Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug, E. G. , Mercy, J. A. , Dahlberg, L. L. , & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malta, D. C. , Silva, M. A. I. , Mello, F. C. M. , Monteiro, R. A. , Sardinha, L. M. V. , Crespo, C. , … Porto, D. L. (2010). Bullying nas escolas brasileiras: Resultados da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do escolar (PeNSE), 2009 [Bullying in Brazilian schools: Results from the National School‐based Health Survey (PeNSE), 2009]. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 15(2), 3065–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks, J. S. , & Audage, N. C. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Retrieved from http://health-equity.lib.umd.edu/932/ [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. , Anselmi, L. , Gallo, E. A. , Fleitlich‐Bilyk, B. , & Bordin, I. A. (2013). Epidemiology of childhood conduct problems in Brazil: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(10), 1527–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. R. , & Streiner, D. L. (1998). PDQ epidemiology. Hamilton, Ontario: B.C. Decker Inc. [Google Scholar]

- O Globo . (July 7th 2017) Estado já teve 632 vítimas de balas perdidas em 2017 [State has already had 632 victims of bullets lost in 2017]. Retrieved from https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/estado-ja-teve-632-vitimas-de-balas-perdidas-em-2017-21558941

- Paula, C. S. , Coutinho, E. S. , Mari, J. J. , Rohde, L. A. , Miguel, E. C. , & Bordin, I. A. (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents from four Brazilian regions. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 37(2), 178–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula, C. S. , Duarte, C. S. , & Bordin, I. A. S. (2007). Prevalence of mental health problems in children and adolescents from the outskirts of Sao Paulo city: Treatment needs and service capacity evaluation. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 29(1), 11–17. 10.1590/S1516-44462006005000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk, G. V. , Salum, G. A. , Sugaya, L. S. , Caye, A. , & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta‐analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. 10.1111/jcpp.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Council of Norway (RCN) . (2010) Latin America Programme (LATINAMERIKA): 7 New Projects Funded – “Results of the November 2009 Call” in attachment. Retrieved from http://www.forskningsradet.no/servlet/Satellite?c=Nyhet&pagename=latinamerika%2FHovedsidemal&cid=1253955242288&lang=en

- Ribeiro, W. S. , Andreoli, S. B. , Ferri, C. P. , Prince, M. , & Mari, J. J. (2009). Exposure to violence and mental health problems in low and middle‐income countries: A literature review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 31(Suppl 2), S49–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters, J. , & Saltzman, W. (1990). Survey of exposure to community violence: Self report version. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. Self report version; Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317316974_Survey_of_Exposure_to_Community_Violence_Self_Report_Version. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, C. , & Abiko, A. K. (2011). Processo de Metropolização no Brasil: Texto Técnico da Escola Politécnica da USP, Departamento de Engenharia de Construção Civil (TT/PCC/028). São Paulo: Escola Politécnica; Retrieved from http://www2.pcc.usp.br/files/text/publications/TT_00028.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rønning, J. A. , Handegaard, B. H. , & Sourander, A. (2004). Self‐perceived peer harassment in a community sample of Norwegian school children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(10), 1067–1079. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, D. K. , Shankar, V. , Hassan, F. , Hunter, W. M. , Jain, D. , Paula, C. S. , … Bordin, I. A. (2010). International variations in harsh child discipline. Pediatrics, 126(3), e701–e711. 10.1542/peds.2008-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S. M. , Afifi, R. A. , Bearinger, L. H. , Blakemore, S. J. , Dick, B. , Ezeh, A. C. , & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, B. D. , Jaycox, L. H. , Kataoka, S. , Rhodes, H. J. , & Vestal, K. D. (2003). Prevalence of child and adolescent exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(4), 247–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh, M. , Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J. , IJzendoorn, M. H. , & Alink, L. R. (2013). Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta‐analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology, 48(2), 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. L. , & Norman, G. R. (1995). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) . (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development ‐ Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República (SPDCA/SEDH), Observatório de Favelas (OF), Laboratório de Análise da Violência (LAV/UERJ) . (2009) Índice de Homicídios na Adolescência: Análise Preliminar dos Homicídios em 267 Municípios Brasileiros com mais de 100 Mil Habitantes Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/brazil/pt/IHA.pdf

- United Nations General Assembly (1989). Convention on the rights of the child ()Treaty Series, 1577:3 New York: United Nations; ISBN: 978‐92‐806‐4555‐2. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN‐Habitat), Petrobras, Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) . (2007) Objetivos de desenvolvimento do milênio: Itaboraí ano de 2007 ‐ Relatório de acompanhamento. Retrieved from Objetivos%2520de%2520Desenvolvimento%2520do%2520Mil%25C3%25AAnio%2520-%2520Itabora%25C3%25AD%25202007%2520,%2520Relat%25C3%25B3rio%2520de%2520Acompanhamento.pdf

- World Health Organization (2010). Violence prevention: The evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77936/1/9789241500845_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]