Abstract

Objectives

The aims of the study were to translate into Persian and culturally adapt the Kessler Psychological Distress Scales, K10 and K6, and to assess their reliability and validity.

Method

The sample was recruited from primary health care (PHC) settings by quota nonprobability sampling, stratified by sex and age. Validity was assessed against the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (v2.1). The psychometric properties of K6 and K10 were also compared with the 12‐item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12).

Results

A total of 818 participants completed the questionnaire. Cronbach's alpha were 0.92 and 0.87 for K6 and K10, respectively. Optimal cutoff scores for detecting any mood or anxiety disorder in the past 30 days were 15 for K10 and 10 for K6. At these cutoff points, the measures had sensitivities of 0.77 and 0.73, specificities of 0.74 and 0.78, and positive predictive values of 0.48 and 0.52, respectively. Psychometric properties of K10 and K6 were similar to GHQ‐12.

Conclusion

Persian K10 and K6 have acceptable psychometric properties as screening instruments for common mental health conditions. Given its brevity and similar psychometric properties to the longer instruments, the Persian K6 appears to be a suitable scale for use in PHC settings and, possibly, epidemiologic studies in Iran.

Keywords: Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, mental illness, Persian, screening, validation study

1. INTRODUCTION

This report describes the adaptation and validation of two short measures of psychological distress for use in primary health care (PHC) settings and epidemiological studies in Iran. Mental disorders, especially disorders of mild to moderate severity are not uncommon in Iranian as in other PHC settings (Jackson, Passamonti, & Kroenke, 2007; Khadivi, Shakeri, & Ghobadi, 2012; Serrano‐Blanco et al., 2010). However, many of the patients with these conditions are not diagnosed or appropriately managed (Bolhari et al., 2012; Mitchell & Coyne, 2007).

Despite ongoing debates regarding the merits of universal screening for common psychiatric disorders such as depression in the general medical settings (Mojtabai, 2017), widely distributed practice guidelines in a number of countries recommend screening for depression in their PHC settings, especially for patient groups at greater risk, such as postpartum women (Austin, Middleton, Reilly, & Highet, 2013; Siu et al., 2016). There is some evidence that selective use of screening measures may improve diagnosis and treatment of common mental disorders and such screening is recommended where there are sufficient resources for further assessment and appropriate follow‐up (Mitchell & Coyne, 2007).

Another potential use of short screening measures is rapid assessment in epidemiological studies (Anderson et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 2003). In the Global Burden of Disease study, mental disorders ranked second in disability‐adjusted life years in both sexes and depressive disorders were the leading cause of disability‐adjusted life years in women (Naghavi et al., 2009). In the last national mental health survey in Iran, 23.6% of participants in the 15–64 years age range met the criteria for a common psychiatric disorders in the past 12 months (Sharifi et al., 2014). The health, social, and economic burden associated with these conditions call for close monitoring of their prevalence and distribution in the population over time. Short measures of psychological distress can supplement data from structured interviews in epidemiologic surveys or be used along with measures of physical health in comprehensive surveys of general health (Hedden, Bose, Gfroerer, & Lipari, 2013; Kessler et al., 2002; Park, Lee, Shearston, & Weitzman, 2017). There is a need for validated brief measures that can be used for rapid and low‐cost assessment in both PHC settings and in large‐scale epidemiologic studies in various settings.

We attempted to address this need in Iran by translating and adapting the 10‐item screening measure originally developed by Kessler and colleagues (K10) and the abbreviated six‐item version of this scale (K6). Originally developed in English for use in the United States, these instruments have been translated to several other languages and extensively used in other settings as measures of nonspecial psychological distress and serious mental illness (SMI; see below) in epidemiologic studies (Aldworth et al., 2010; Arnaud et al., 2010; Carra et al., 2011; Donker et al., 2010; Fassaert et al., 2009; Han, Gfroerer, Colpe, Barker, & Colliver, 2011; Kessler et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 2010; Sakurai, Nishi, Kondo, Yanagida, & Kawakami, 2011). These measures have also been clinically used as screeners for establishing treatment referrals in PHC settings and for disability claimants (Allen et al., 2012; Cornelius, Groothoff, van der Klink, & Brouwer, 2013; Donker et al., 2010; Fassaert et al., 2009; Furukawa, Kessler, Slade, & Andrews, 2003; Kessler et al., 2010). We further compared the psychometric properties of these measures with the 12‐item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12) that has been validated and extensively used in Iran (Bahremand et al., 2014; Emami, Ghazinour, Rezaeishiraz, & Richter, 2007; Heidari, Feizi, Roohafza, Hassanzadeh Keshteli, & Adibi, 2017; Montazeri et al., 2005) and other countries (Danielsson, Lundin, Allebeck, & Agardh, 2016; Diniz et al., 2014; Padron, Galan, & Rodriguez‐Artalejo, 2014; Pope et al., 2015).

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample

The sample included adult primary care patients of general practitioners and family physicians in five urban or rural health centers in three provinces in Iran. Participants were recruited between April and September 2014. Nonprobability quota sampling was used to recruit almost equal proportions of both sexes and participants above and below 35 years of age.

All patients in the 15 to 64 years age range who were able to communicate in Persian were eligible for this study. Those with a medical condition or cognitive disability that made them unable to complete the interview were excluded. Participation was voluntary, and all participants gave informed consent. Participants were informed that the data will remain confidential and the analyses will be performed anonymously. For Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) questions regarding substance abuse, these reassurances were reiterated and the participants were again told that they do have the right to refuse to answer the questions.

2.2. Fieldwork

The study was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the study questionnaires, consisting of K10, K6, CIDI 2.1, and GHQ‐12 along with a demographic questionnaire were administered. Participants who had a history of inpatient psychiatric admissions or had a positive lifetime history of psychotic symptoms were reinterviewed through telephone by a psychiatrist using the Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (SCID; Sharifi et al., 2009). A total of 818 patients participated in the study; 36 SCID telephone interviews were completed.

Four hundred participants were invited to complete the K10, K6, and GHQ‐12 questionnaires for a second time within 2 weeks of the first interview for assessment of test–retest reliability. Of these, 195 (48.8%) completed these in‐person reinterviews.

2.3. Assessments

2.3.1. K10 and K6

K10 consists of 10 questions assessing nonspecific psychological distress. The questions ask how frequently in the past month the participant has felt tired out for no good reason (Q1), nervous (Q2), so nervous that nothing could calm them down (Q3), disappointed or hopeless (Q4), restless or fidgety (Q5), so restless that they could not sit still (Q6), depressed (Q7), so depressed that nothing could cheer them up (Q8), feeling that everything was an effort (Q9), and feeling worthless (Q10). Responses to each question were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale, ranging from “never” (=0) to “always” (=4). The responses were summed, providing a total score between 0 and 40. K6 is based on responses to Q2, Q4, Q5, Q8, Q9, and Q10 with a total score ranging from 0 to 24.

K10 and K6 are available in both self‐administered and interview versions. In this study, we used the interview version of the instruments.

Translation and cultural adaptation of the scale followed the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines as described below:

Froward translation: A bilingual psychiatrist from the research team (corresponding author) translated the scale into Persian (Farsi).

First expert panel: An expert panel consisted of four psychiatrists and an epidemiologist reviewed and edited the translation draft. Expressions that were deemed confusing or culturally inappropriate were revised through discussion with the primary translator. Specifically, the panel recommended alternative expressions and clarifications of the questions inquiring about feeling depressed and feeling tired out for no good reason. The panel noted that the literal translation of the expression “feeling nervous” in Persian is close to the concept of feeling angry, which may be confusing to some participants. The panel recommended adding a conceptually equivalent term for “anxious” to the item for clarity. They also recommended replacing “how often” with “how much” because the literal translation of the “how often” is not commonly used and difficult to understand for many Persian speakers, especially those with lower levels of education.

Back translation: Another bilingual psychiatrist back translated the draft into English. The back translated and the original English versions of the instrument were compared for accuracy.

Pretesting and cognitive interviewing: Eleven patients (10 males, one female) from a methadone maintenance treatment program participated in the pretest phase. Mean and median age of the participants were 37.9 and 35 years, respectively. Participants were debriefed after responding to each of the K10 questions by further questions as to (a) “What was the purpose of this question?” (b) “What was the question asking for?” and (c) “Were there any words or phrases you could not understand?” The debriefing process was conducted through an in‐depth interview by a trained interviewer. All responses were recorded under the relevant item.

Second expert panel: Responses obtained from cognitive interviews were presented to the expert panel described above, and a final draft of the questionnaire was prepared based on the panel discussions.

The final version was sent to Professor Ronald Kessler who has developed the instrument. The translation process and the final Persian version was reviewed by anonymous reviewers from WHO. The Persian K10 is approved and now is available at Harvard Medical School–National Comorbidity webpage (https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/k6_scales.php).

2.3.2. General Health Questionnaire 12

The Persian translation of the full scale and the brief 12‐item version of GHQ have been validated before (Ebadi et al., 2002). Item scores ranged from 0 to 3, and the total score for GHQ‐12 ranged from 0 to 36.

2.3.3. CIDI version 2.1

Diagnoses of any major depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders (including panic disorder with/without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder) in the past 30 days (12 months for psychotic and bipolar disorders) were ascertained using the CIDI 2.1. We used the 30‐day diagnoses for common psychiatric disorders to better match the 30‐day time frame of K10 and K6. The Persian translation of the CIDI 2.1 has been previously validated (Alaghband Rad, 2003), and the instrument has been used in the Iranian Mental Health Survey (Rahimi‐Movaghar et al., 2014). Participants who screened positive for psychotic symptoms in their lifetime by CIDI 2.1 were reassessed via telephone interviews using the SCID to ascertain psychotic disorders in past 12 months. Telephone‐administered Persian version of SCID‐I for psychotic disorders has been shown to be comparable with the face‐to‐face administered version of the instrument in terms of sensitivity (Hajebi et al., 2012). All interviewers had master's degrees in Clinical Psychology and had prior experience with administering CIDI.

In addition to individual disorders, we assessed SMI defined by (a) diagnoses of bipolar disorder (based on CIDI 2.1) or psychotic disorders in past 12 months (based on telephone interview using SCID), (b) any suicide attempt in the past 12 months, or (c) severe impairment in at least two domains of functioning (based on the Sheehan Disability Scale [SDS] described below) along with a diagnosis of any depressive or anxiety disorder in the past 30 days.

2.3.4. Sheehan Disability Scale

The SDS has been extensively used in past research for assessment of disability due to psychological problems (Colpe et al., 2010; Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Sharifi et al., 2014). The questionnaire asks the participants about their worst period of functioning when symptoms were most severe during the past year and assesses the impact of the disorder on the different aspects of functioning such as housework, occupation, social life, and interpersonal relations. The participants use a visual analogue scale (from 0 to 100) to rate the severity of disability ranging from “no impact” (=0) to “very severe impact” (=100). Validity and reliability of the Persian version of SDS in the general population and psychiatric patients has been previously assessed (Amin‐Esmaeili et al., 2014).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Psychometric properties of K10, K6, and GHQ‐12 were assessed using several techniques. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's alpha and item‐total correlations. Test–retest reliability was assessed using Spearman's correlation coefficients. In addition, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC) for predicting any mood or anxiety disorders and SMI were obtained from the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. Spearman's rank‐order correlation coefficients were used to assess correlations among K10, K6, and GHQ‐12. All analyses were conducted using PASW 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, 2010) and STATA 12.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA, 2011) softwares.

3. RESULTS

The 818 participants comprised 386 men and 432 women with a mean age of 35.4 ± 0.4. The majority (77.9%) was married; 19.7% were single, and 2.4% were previously married. Only a small minority (2.4%) was illiterate; 73.2% had high school education and 24.8% had college education. Approximately one out of every four (24%) met the CIDI criteria for a depressive or anxiety disorder during the past 30 days. SMI based on the criteria described above was found in 11.6% of the participants.

3.1. Internal consistency

The Cronbach's alpha values for K10, K6, and GHQ‐12 were 0.92, 0.87, and 0.87, respectively. The interitem and item‐total correlations for K10 and K6 are reported in Table 1. Item‐total correlation coefficients ranged from 0.59 to 0.80 for K10 and 0.59 to 0.73 for K6.

Table 1.

Item‐total correlations and Cronbach's alpha values for K6 and K10

| Questions | Item‐total correlation (K6) | Item‐total correlation (K10) | Cronbach's alpha if item deleted | Item–item correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | ||||

| Q1 (tired out for no good reason) | ‐ | 0.59 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| Q2 (nervous) | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.91 | ‐ | 1 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.44 |

| Q3 (so nervous that nothing could calm you down) | ‐ | 0.72 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.49 |

| Q4 (disappointed or hopeless) | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.61 |

| Q5 (restless or fidgety) | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| Q6 (so restless that you could not sit still) | ‐ | 0.71 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Q7 (depressed) | ‐ | 0.77 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.54 |

| Q8 (so depressed that nothing could cheer you up) | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| Q9 (everything was an effort) | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.92 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.50 |

| Q10 (worthless) | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.91 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 |

3.2. Test–retest reliability

Table 2 presents the 2‐week test–retest reliability values for individual items of K10 and K6. Spearman's correlations for individual questions ranged from 0.26 for Q3 (feeling so nervous that nothing could calm them down) to 0.46 for Q10 (feeling worthless). Spearman's correlations for global K10 and K6 scores were 0.51 and 0.50, respectively (p value < 0.001).

Table 2.

Test–retest reliability of K10 and K6 questions

| Items | Spearman correlation coefficients |

|---|---|

| Q1 | 0.40 |

| Q2a | 0.32 |

| Q3 | 0.26 |

| Q4a | 0.42 |

| Q5a | 0.37 |

| Q6 | 0.29 |

| Q7 | 0.45 |

| Q8a | 0.42 |

| Q9a | 0.44 |

| Q10a | 0.46 |

| Total score of K6 | 0.50 |

| Total score of K10 | 0.51 |

Items included in K6.

3.3. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC

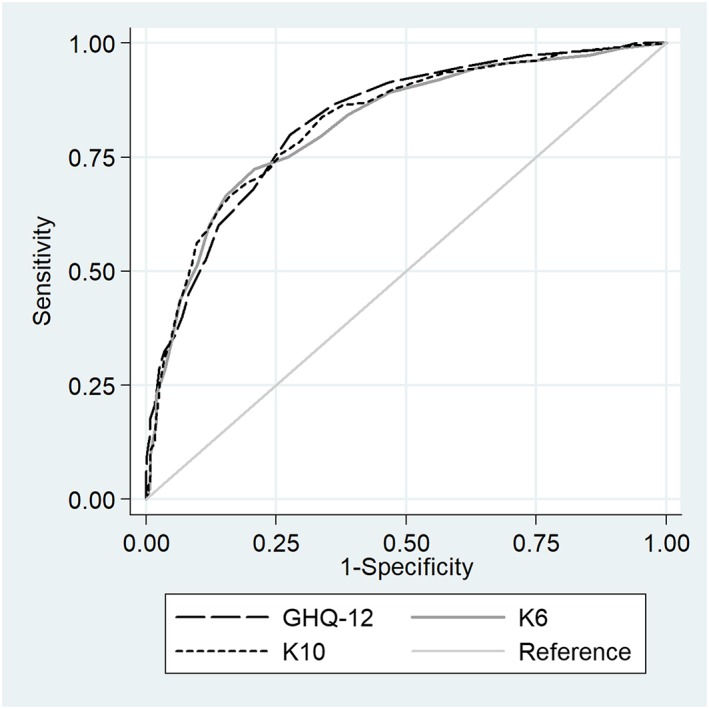

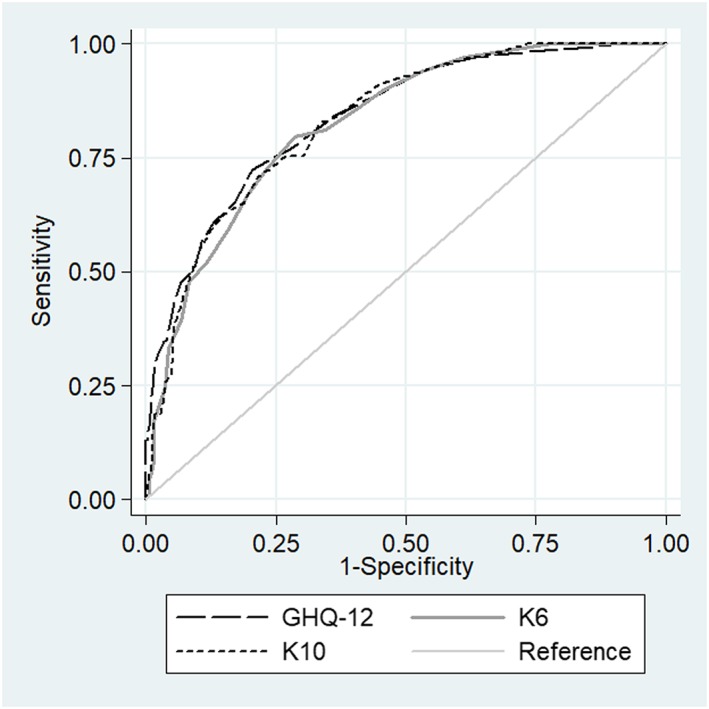

Sensitivity, specificity, PPVs, and NPVs of the instruments for detecting any mood or anxiety disorders as well as SMI in the past 30 days are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The optimal cutoff scores of K10 for predicting any mood or anxiety disorder and SMI were 15 and 19, respectively. The optimal cutoff score of K6 was 10 for predicting both any mood or anxiety disorders and SMI. The corresponding cutoff scores for GHQ‐12 were 11 and 13, respectively. AUC for all three scales were over 0.80 for screening for any mood or anxiety disorders and for SMI in the past 30 days (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for different cutoff scores of the K10, K6, and GHQ‐12 for predicting any mood or anxiety disorder in the past 30 days

| Tools | Cutoffs | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Prevalence (by each cutoff) | Youden's J statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K10 | ≥12 | 0.865 | 0.622 | 0.419 | 0.899 | 0.495 | 0.487 |

| ≥13 | 0.838 | 0.662 | 0.439 | 0.868 | 0.458 | 0.500 | |

| ≥14 | 0.784 | 0.704 | 0.456 | 0.812 | 0.413 | 0.488 | |

| ≥15 | 0.757 | 0.741 | 0.480 | 0.771 | 0.378 | 0.498 | |

| ≥16 | 0.714 | 0.771 | 0.496 | 0.716 | 0.345 | 0.485 | |

| ≥17 | 0.692 | 0.808 | 0.533 | 0.663 | 0.312 | 0.500 | |

| ≥18 | 0.665 | 0.839 | 0.565 | 0.604 | 0.282 | 0.504 | |

| K6 | ≥7 | 0.843 | 0.612 | 0.407 | 0.887 | 0.497 | 0.455 |

| ≥8 | 0.795 | 0.666 | 0.429 | 0.838 | 0.445 | 0.460 | |

| ≥9 | 0.751 | 0.726 | 0.464 | 0.777 | 0.389 | 0.477 | |

| ≥10 | 0.724 | 0.792 | 0.523 | 0.705 | 0.332 | 0.516 | |

| ≥11 | 0.665 | 0.847 | 0.579 | 0.591 | 0.276 | 0.512 | |

| ≥12 | 0.600 | 0.879 | 0.610 | 0.489 | 0.236 | 0.479 | |

| ≥13 | 0.514 | 0.901 | 0.621 | 0.392 | 0.199 | 0.453 | |

| GHQ‐12 | ≥8 | 0.941 | 0.424 | 0.340 | 0.968 | 0.664 | 0.364 |

| ≥9 | 0.914 | 0.536 | 0.383 | 0.944 | 0.572 | 0.450 | |

| ≥10 | 0.865 | 0.640 | 0.432 | 0.894 | 0.481 | 0.505 | |

| ≥11 | 0.800 | 0.723 | 0.477 | 0.814 | 0.403 | 0.523 | |

| ≥12 | 0.681 | 0.793 | 0.510 | 0.672 | 0.321 | 0.474 | |

| ≥13 | 0.600 | 0.861 | 0.576 | 0.525 | 0.250 | 0.461 | |

| ≥14 | 0.524 | 0.886 | 0.592 | 0.432 | 0.213 | 0.410 |

Note. Optimal cutoff scores are in bold and italic font. GHQ‐12: 12‐item General Health Questionnaire; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for different cutoff scores of K10, K6, and GHQ‐12 for predicting serious mental illness (SMI) in the past 30 days

| Tools | Cutoffs | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Prevalence (by each cutoff) | Youden's J statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K10 | ≥16 | 0.754 | 0.696 | 0.199 | 0.925 | 0.345 | 0.449 |

| ≥17 | 0.754 | 0.732 | 0.220 | 0.916 | 0.312 | 0.486 | |

| ≥18 | 0.725 | 0.762 | 0.234 | 0.896 | 0.282 | 0.487 | |

| ≥19 | 0.710 | 0.785 | 0.248 | 0.881 | 0.261 | 0.495 | |

| ≥20 | 0.652 | 0.811 | 0.257 | 0.844 | 0.231 | 0.463 | |

| ≥21 | 0.638 | 0.835 | 0.279 | 0.820 | 0.208 | 0.473 | |

| ≥22 | 0.623 | 0.852 | 0.297 | 0.797 | 0.191 | 0.475 | |

| K6 | ≥7 | 0.899 | 0.544 | 0.165 | 0.978 | 0.497 | 0.442 |

| ≥8 | 0.855 | 0.597 | 0.175 | 0.965 | 0.444 | 0.452 | |

| ≥9 | 0.812 | 0.655 | 0.191 | 0.948 | 0.388 | 0.467 | |

| ≥10 | 0.797 | 0.714 | 0.218 | 0.934 | 0.332 | 0.511 | |

| ≥11 | 0.725 | 0.769 | 0.239 | 0.893 | 0.276 | 0.494 | |

| ≥12 | 0.667 | 0.807 | 0.257 | 0.853 | 0.236 | 0.474 | |

| ≥13 | 0.594 | 0.841 | 0.272 | 0.797 | 0.199 | 0.435 | |

| GHQ‐12 | ≥10 | 0.884 | 0.561 | 0.168 | 0.974 | 0.480 | 0.445 |

| ≥11 | 0.841 | 0.641 | 0.190 | 0.957 | 0.403 | 0.481 | |

| ≥12 | 0.768 | 0.724 | 0.218 | 0.922 | 0.321 | 0.492 | |

| ≥13 | 0.725 | 0.796 | 0.262 | 0.881 | 0.252 | 0.520 | |

| ≥14 | 0.652 | 0.830 | 0.277 | 0.830 | 0.214 | 0.482 | |

| ≥15 | 0.609 | 0.870 | 0.320 | 0.768 | 0.173 | 0.479 | |

| ≥16 | 0.565 | 0.893 | 0.346 | 0.711 | 0.149 | 0.458 |

Note. Optimal cutoff scores are in bold and italic font. GHQ‐12: 12‐item General Health Questionnaire; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for detection of any mood or anxiety disorder in the past 30 days by K10, K6, and GHQ‐12. GHQ‐12: 12‐item General Health Questionnaire

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for detection of serious mental illness in the past 30 days by K10, K6, and GHQ‐12. GHQ‐12: 12‐item General Health Questionnaire

K6 and K10 total scores were strongly correlated with the GHQ‐12 scores. The Spearman's correlations with GHQ‐12 was 0.60 for K10 and 0.66 for K6 (both p values < 0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Reliability and validity of the scales

This study assessed the reliability of K10 and K6 questionnaires and their validity against CIDI mood and anxiety disorders and SMI. Furthermore, we compared these questionnaires with a commonly used screening questionnaire, the GHQ‐12. K10 and K6 appear to have acceptable reliability and validity and comparable psychometric properties to the longer GHQ‐12 questionnaire, which is commonly used for screening mild to moderate psychiatric disorders in this setting.

Cronbach's alpha values of above 0.90 for K10 and above 0.80 for K6 and GHQ‐12 indicate excellent reliability and internal consistency. The internal consistency of K10 and K6 were similar, despite the significantly shorter length of K6. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the Persian K6 was similar to the original English version (0.89; Kessler et al., 2003). Arnaud et al. (2010) reported Cronbach's alpha values of 0.84 and 0.76 for the French versions of K10 and K6, respectively. The corresponding figures were 0.84 and 0.90 in another study using the Italian version of K10 and K6 (Carra et al., 2011).

Test–retest reliability of K10 and K6 items ranged from 0.26 to 0.46. To the best of our knowledge, the test–retest reliability of the K6 has been examined only in one study from China (Lee et al., 2012). In that study, correlation among items between the first telephone survey response and the telephone reinterview response within a month ranged from 0.5 to 0.6 (Lee et al., 2012). Relatively low values of test–retest reliability might be due to changes in the mental status of the participants at the time of the reinterview. In this study, retest data were collected almost 2 weeks after the original assessment. Although the measures assess emotional states over the past 30 days, participants tend to recall more recent experiences. For example, in a study by Kessler et al. (2010) when asked about the time when they felt worst in the past year, 80% of the participants reported the past month as their worst month. Thus, the actual overlap in the periods remembered across the 2‐week test–retest assessments may have been quite small.

4.2. Determining optimal cutoff scores

The AUC for the Persian K10 and K6 is comparable with the English, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and Dutch versions of the instrument (ranging from 0.76 to 0.89; (Carra et al., 2011; Cornelius et al., 2013; Kessler et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Sakurai et al., 2011). However, different cutoff scores have been proposed for these instruments in different studies and in different settings. In a French study including patients with alcohol use disorders referred to the emergency services, cutoff scores of 14 and 10 were proposed for K10 and K6, respectively (Arnaud et al., 2010). In another study involving screening of any mood or anxiety disorders in PHC settings, cutoff scores of 12 for K10 (87% sensitivity and 70% specificity) and 7 for K6 (82% sensitivity and 70% specificity) were proposed (Carra et al., 2011). These cutoff scores are lower than the ≥13 cutoff for K6 proposed in the original study by Kessler et al. (2003). However, the Kessler et al. study used SCID diagnosis of SMI as the criterion and, more importantly, sought to equalize false‐positive and false‐negative results in the weighted sample rather than find a psychometrically optimal cutoff score.

Similar to the study by Lee et al. (2012) from China, we found that the Persian K6 performed better in detecting any mood or anxiety disorders than SMI. Lee et al. commented that K6 is more suitable for “screening out” rather than “screening in” SMI. However, the results were different in Carra et al. (2011) study from Italy, which used SCID diagnoses as the criteria. In that study, K10 and K6 were more accurate in detecting SCID SMI than SCID diagnoses of mood or anxiety disorders. The variations in optimal cutoff scores according to setting, composition of participants, and the criterion used suggest that different cutoff scores may be recommended for different contexts and different purposes. When an instrument is used for screening for possible cases in a PHC setting, where the final diagnosis and treatment plans are provided by other approach such as detailed interview by physicians, higher sensitivity is more desirable. Another factor in deciding the cutoff scores is consideration of financial and psychological burden associated with potential overdiagnosis. A higher cutoff score maybe desirable when the goal is to limit false‐positive cases.

Along these lines, some investigators have proposed using stratum specific likelihood ratios for specific ranges of cutoff scores (Carra et al., 2011; Schmitz, Kruse, & Tress, 2000). The stratum specific likelihood ratios can be easily computed from data on sensitivity and specificity such as reported in Table 3. Providing information on sensitivity, specificity for a range of cutoff scores along with prevalence estimates of SMI and depression and anxiety disorders in this sample also allows other investigators and potential users of Persian K10 and K6 to estimate PPV and NPV for their specific setting and choose a cutoff score that best meets their needs.

When used in epidemiologic studies to provide an estimate of the prevalence of mental disorders, a balance between false‐positive and false‐negative cases may be desirable. Kessler et al. (2003) recommended a cutoff score of ≥13 on K6 for estimating the prevalence of SMI in the past 12 months in population surveys in the United States with the rationale that this cutoff would produce equal numbers of false‐positive and false‐negative cases, which will cancel each other out and thus provide a consistent estimate of the prevalence of SMI. Availability of psychometric data for the different cutoff points on the Persian K10 and K6 in this study would similarly enable Iranian researchers to choose cutoff scores that would provide the most accurate prevalence estimates in this setting.

4.3. Comparison of K10 and K6 with GHQ

The study found acceptable convergent validity between K10, K6, and GHQ. Our results are similar to those of Patel et al. (2008) who reported correlation coefficient of 0.68 and 0.58 between GHQ on the one hand and K10 and K6, respectively, on the other hand. The results of the current study show that the psychometric properties of K10 are similar to those of GHQ‐12 and slightly better than those for K6. However, K6 is significantly shorter and thus a suitable candidate for screening in PHC centers and large‐scale general population surveys.

4.4. Limitations

Two limitations of this study should be considered in evaluating its results. First, the sample was selected from PHC settings. The results may be different in general population samples. Future research should examine the reliability and validity of these measures when used in general population samples. Second, the diagnoses were based on structured interview instruments and may not fully correspond with clinician diagnoses. Future research needs to assess the clinical utility of these instruments in PHC settings.

5. CONCLUSION

In the context of the above limitations, the results of this study suggest that K10 and K6 are potentially useful instruments for the purpose of screening for common mental disorders in PHC settings and, possibly, in community settings. These measures have good internal consistency and test–retest reliability, correlate strongly with the longer GHQ‐12 measure, and have adequate sensitivity and specificity for detecting mood and anxiety disorders ascertained using a structured interview instrument. Future users of the K10 and K6 should select the optimal cutoff scores on these instruments based on their own needs and in view of the strengths and limitations of these instruments. However, the instruments appear have low PPVs for detecting the less common SMI in this setting. Given the low prevalence of SMI in the community, the K10 and K6 may not be suitable as screening instruments as they will miss the majority of cases. With the growing appreciation of the role of general medical care services in managing SMI, there remains a need for brief and user‐friendly screening measures for these conditions in Iran as in other countries.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was conducted with the support of the Iranian Ministry of Health and the research deputy of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences through the contract number 2589/130. The authors wish to express their appreciation to Dr. Ronald Kessler and the WHO anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable feedback on the Persian translation of K10. We would like to thank Dr. Mahdavi for conducting the telephone interviews using SCID and field managers Fariba Rezai, Shohreh Nasr, and Leila Moazami from Shiraz, Zanjan, and Tehran Universities of Medical Sciences. We would also like to thank the interviewers Sara Ansari, Tahereh Ghanbarian, Zahra Asgari Kouchi, and Mehdi Janbazi from Shirza; Parisa Molaei and Abolfaz Babaei from Zanjan; and Farideh Kolahi Heshmat from Tehran for their contribution in data gathering. We also wish to express our gratitude to Roya Azadi for data entry and to Kebria Adli and Mansoureh Azami for their administrative assistance.

Hajebi A, Motevalian A, Amin‐Esmaeili M, et al. Adaptation and validation of short scales for assessment of psychological distress in Iran: The Persian K10 and K6 . Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27:e1726 10.1002/mpr.1726

REFERENCES

- Alaghband Rad, J. (2003). Study of the reliability, validity, and feasibility of Farsi translation of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) In Ahmadi Abhari S. A., Malakooti K., Nasr Esfahani M., Razzaghi E. M., Sadeghi M., & Yasamy M. T. (Eds.), Mental health effects of Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in a war‐torn population of Iran: An epidemiological and financial study of the consequences of the Kuwaiti oil well fire disasters in the aftermath of Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1991, United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) Monitoring and Assessment Project. Tehran, Iran: Islamic Republic of Iran Ministry of Health, Committee for assessment and follow up for damages resulting from the Iraq–Kuwait War. [Google Scholar]

- Aldworth, J. , Colpe, L. J. , Gfroerer, J. C. , Novak, S. P. , Chromy, J. R. , Barker, P. R. , … Spagnola, K. (2010). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Mental Health Surveillance Study: Calibration analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(Suppl 1), 61–87. 10.1002/mpr.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J. , Annells, M. , Clark, E. , Lang, L. , Nunn, R. , Petrie, E. , & Robins, A. (2012). Mixed methods evaluation research for a mental health screening and referral clinical pathway. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 9(3), 172–185. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin‐Esmaeili, M. , Motevalian, A. , Rahimi‐Movaghar, A. , Hajebi, A. , Hefazi, M. , Radgoodarzi, R. , & Sharifi, V. (2014). The translation and psychometric assessment of the persian version of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 9(3), 125–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T. M. , Sunderland, M. , Andrews, G. , Titov, N. , Dear, B. F. , & Sachdev, P. S. (2012). The 10‐item Kessler Psychological Distress Measure (K10) as a screening instrument in older individuals. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318252e7a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, B. , Malet, L. , Teissedre, F. , Izaute, M. , Moustafa, F. , Geneste, J. , … Brousse, G. (2010). Validity study of Kessler's psychological distress scales conducted among patients admitted to French emergency department for alcohol consumption‐related disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(7), 1235–1245. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, M. P. , Middleton, P. , Reilly, N. M. , & Highet, N. J. (2013). Detection and management of mood disorders in the maternity setting: The Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines. Women and Birth Journal, 26(1), 2–9. 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahremand, M. , Rai, A. , Alikhani, M. , Mohammadi, S. , Shahebrahimi, K. , & Janjani, P. (2014). Relationship between family functioning and mental health considering the mediating role of resiliency in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(3), 254–259. 10.5539/gjhs.v7n3p254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhari, J. , Ahmadkhaniha, H. , Hajebi, A. , Bagheri Yazdi, S. A. , Naserbakht, M. , Karimi‐Kisomi, I. , & Tahmasebi, S. (2012). Evaluation of mental health program integration into the primary health care system of Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 17(4), 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Carra, G. , Sciarini, P. , Segagni‐Lusignani, G. , Clerici, M. , Montomoli, C. , & Kessler, R. C. (2011). Do they actually work across borders? Evaluation of two measures of psychological distress as screening instruments in a non Anglo‐Saxon country. European Psychiatry, 26(2), 122–127. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.008 S0924‐9338 (10)00116‐1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpe, L. J. , Barker, P. R. , Karg, R. S. , Batts, K. R. , Morton, K. B. , Gfroerer, J. C. , … Aldworth, J. (2010). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Mental Health Surveillance Study: Calibration study design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(Suppl 1), 36–48. 10.1002/mpr.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius, B. L. , Groothoff, J. W. , van der Klink, J. J. , & Brouwer, S. (2013). The performance of the K10, K6 and GHQ‐12 to screen for present state DSM‐IV disorders among disability claimants. BMC Public Health, 13, 128 10.1186/1471-2458-13-128. 1471‐2458‐13‐128[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson, A. K. , Lundin, A. , Allebeck, P. , & Agardh, E. (2016). Cannabis use and psychological distress: An 8‐year prospective population‐based study among Swedish men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 59, 18–23. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere, K. , Bruffaerts, R. , Posada‐Villa, J. , Gasquet, I. , Kovess, V. , Lepine, J. P. , … Chatterji, S. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA, 291(21), 2581–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, B. S. , Reynolds, C. F. 3rd , Butters, M. A. , Dew, M. A. , Firmo, J. O. , Lima‐Costa, M. F. , & Castro‐Costa, E. (2014). The effect of gender, age, and symptom severity in late‐life depression on the risk of all‐cause mortality: The Bambui Cohort Study of Aging. Depression and Anxiety, 31(9), 787–795. 10.1002/da.22226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker, T. , Comijs, H. , Cuijpers, P. , Terluin, B. , Nolen, W. , Zitman, F. , & Penninx, B. (2010). The validity of the Dutch K10 and extended K10 screening scales for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research, 176(1), 45–50. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.012 S0165‐1781 (09)00020‐1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebadi, M. , Harirchi, A. , Shariati, M. , Garmaroudi, G. R. , Fateh, A. , & Montazeri, A. (2002). Translation, reliability and validity of the 12‐item general health questionnaire among young people in Iran. Payesh, 1(3), 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, H. , Ghazinour, M. , Rezaeishiraz, H. , & Richter, J. (2007). Mental health of adolescents in Tehran, Iran. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), 571–576. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassaert, T. , De Wit, M. A. , Tuinebreijer, W. C. , Wouters, H. , Verhoeff, A. P. , Beekman, A. T. , & Dekker, J. (2009). Psychometric properties of an interviewer‐administered version of the Kessler Psychological Distress scale (K10) among Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish respondents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18(3), 159–168. 10.1002/mpr.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, T. A. , Kessler, R. C. , Slade, T. , & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well‐Being. Psychological Medicine, 33(2), 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajebi, A. , Motevalian, A. , Amin‐Esmaeili, M. , Hefazi, M. , Radgoodarzi, R. , Rahimi‐Movaghar, A. , & Sharifi, V. (2012). Telephone versus face‐to‐face administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, for diagnosis of psychotic disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(5), 579–583. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. , Gfroerer, J. C. , Colpe, L. J. , Barker, P. R. , & Colliver, J. D. (2011). Serious psychological distress and mental health service use among community‐dwelling older U.S. adults. Psychiatric Services, 62(3), 291–298. 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden, S. L. , Bose, J. , Gfroerer, J. C. , & Lipari, R. N. (2013). Revised estimates of mental illness from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.The CBHSQ Report Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). [PubMed]

- Heidari, Z. , Feizi, A. , Roohafza, H. , Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A. , & Adibi, P. (2017). Somatoform symptoms profiles in relation to psychological disorders—A population classification analysis in a large sample of general adults. Psychiatry Research, 254, 173–178. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. L. , Passamonti, M. , & Kroenke, K. (2007). Outcome and impact of mental disorders in primary care at 5 years. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(3), 270–276. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180314b59 PSY.0b013e3180314b59 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Andrews, G. , Colpe, L. J. , Hiripi, E. , Mroczek, D. K. , Normand, S. L. , … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non‐specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Barker, P. R. , Colpe, L. J. , Epstein, J. F. , Gfroerer, J. C. , Hiripi, E. , … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Green, J. G. , Gruber, M. J. , Sampson, N. A. , Bromet, E. , Cuitan, M. , … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2010). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(Suppl 1), 4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadivi, R. , Shakeri, M. , & Ghobadi, S. (2012). The efficiency of mental health integration in primary health care: A ten‐year study. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(Suppl 1), S139–S145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Tsang, A. , Ng, K. L. , Ma, Y. L. , Guo, W. , Mak, A. , & Kwok, K. (2012). Performance of the 6‐item Kessler scale for measuring serious mental illness in Hong Kong. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(5), 584–592. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.10.001 S0010‐440X (11)00197‐0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. J. , & Coyne, J. C. (2007). Do ultra‐short screening instruments accurately detect depression in primary care? A pooled analysis and meta‐analysis of 22 studies. British Journal of General Practice, 57(535), 144–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai, R. (2017). Universal depression screening to improve depression outcomes in primary care: Sounds good, but where is the evidence? Psychiatric Services, 68(7), 724–726. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri, A. , Baradaran, H. , Omidvari, S. , Azin, S. A. , Ebadi, M. , Garmaroudi, G. , … Shariati, M. (2005). Psychological distress among Bam earthquake survivors in Iran: A population‐based study. BMC Public Health, 5, 4 10.1186/1471-2458-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, M. , Abolhassani, F. , Pourmalek, F. , Lakeh, M. , Jafari, N. , Vaseghi, S. , … Kazemeini, H. (2009). The burden of disease and injury in Iran 2003. Population Health Metrics, 7, 9 10.1186/1478-7954-7-9 1478‐7954‐7‐9 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padron, A. , Galan, I. , & Rodriguez‐Artalejo, F. (2014). Second‐hand smoke exposure and psychological distress in adolescents. A population‐based study. Tobacco Control, 23(4), 302–307. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. H. , Lee, L. , Shearston, J. A. , & Weitzman, M. (2017). Patterns of electronic cigarette use and level of psychological distress. PLoS one, 12(3), e0173625 10.1371/journal.pone.0173625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V. , Araya, R. , Chowdhary, N. , King, M. , Kirkwood, B. , Nayak, S. , … Weiss, H. A. (2008). Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: A comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychological Medicine, 38(2), 221–228. 10.1017/s0033291707002334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope, D. , Tisdall, R. , Middleton, J. , Verma, A. , van Ameijden, E. , Birt, C. , … Bruce, N. G. (2015). Quality of and access to green space in relation to psychological distress: Results from a population‐based cross‐sectional study as part of the EURO‐URHIS 2 project. European Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 35–38. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi‐Movaghar, A. , Amin‐Esmaeili, M. , Sharifi, V. , Hajebi, A. , Hefazi, M. , Rad, G. R. , & Motevalian, S. A. (2014). The Iranian mental health survey: Design and field procedures. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 9(2), 96–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, K. , Nishi, A. , Kondo, K. , Yanagida, K. , & Kawakami, N. (2011). Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 65(5), 434–441. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, N. , Kruse, J. , & Tress, W. (2000). Application of stratum‐specific likelihood ratios in mental health screening. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 35(8), 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano‐Blanco, A. , Palao, D. J. , Luciano, J. V. , Pinto‐Meza, A. , Lujan, L. , Fernandez, A. , … Haro, J. M. (2010). Prevalence of mental disorders in primary care: Results from the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care study (DASMAP). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(2), 201–210. 10.1007/s00127-009-0056-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, V. , Amin‐Esmaeili, M. , Hajebi, A. , Motevalian, A. , Radgoodarzi, R. , Hefazi, M. , & Rahimi‐Movaghar, A. (2014). Twelve‐month prevalence and correlates of psychiatric disorders in Iran: The Iranian Mental Health Survey, 2011. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 18(2), 76–84. 10.5182/AIM.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, V. , Assadi, S. M. , Mohammadi, M. R. , Amini, H. , Kaviani, H. , Semnani, Y. , … Jalali, M. (2009). A Persian translation of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: Psychometric properties. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(1), 86–91. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu, A. L. , Bibbins‐Domingo, K. , Grossman, D. C. , Baumann, L. C. , Davidson, K. W. , Ebell, M. , … Pignone, M. P. (2016). Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama, 315(4), 380–387. 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]