Abstract

HowNutsAreTheDutch (Dutch: HoeGekIsNL) is a national crowdsourcing study designed to investigate multiple continuous mental health dimensions in a sample from the general population (n = 12,503). Its main objective is to create an empirically based representation of mental strengths and vulnerabilities, accounting for (i) dimensionality and heterogeneity, (ii) interactivity between symptoms and strengths, and (iii) intra‐individual variability. To do so, HowNutsAreTheDutch (HND) makes use of an internet platform that allows participants to (a) compare themselves to other participants via cross‐sectional questionnaires and (b) to monitor themselves three times a day for 30 days with an intensive longitudinal diary study via their smartphone. These data enable for personalized feedback to participants, a study of profiles of mental strengths and weaknesses, and zooming into the fine‐grained level of dynamic relationships between variables over time. Measuring both psychiatric symptomatology and mental strengths and resources enables for an investigation of their interactions, which may underlie the wide variety of observed mental states in the population. The present paper describes the applied methods and technology, and presents the sample characteristics. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: mental symptoms, mental strengths and resources, longitudinal, ecological momentary assessment, crowdsourcing

Introduction

The debate about the optimal way to define and classify mental health problems has intensified over the past three decades (Kapur et al., 2012; Kendler and First, 2010; Kendler et al., 2011; Wakefield, 1992). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) brought standardization to a field that used to be heavily fragmented, and allowed for a shared clinical language. Nonetheless, DSM categories have also been criticized for their lack of empirical support and the absence of an underlying theoretical framework (Kapur et al., 2012; Kendler et al., 2011; Wardenaar and de Jonge, 2013; Whooley, 2014). Although the DSM system is mandatory in psychiatric practice, scientists raised concerns about its use, and argued that the current classification system hampers our understanding of psychiatric disorders and can lead to scientific stagnation (Dehue, 2014; Insel, 2013; Kapur et al., 2012; Whooley, 2014). In the following we propose three ways in which research can help to improve the DSM system into an empirically based etiological system.

First, the descriptive consensus‐based DSM categories imply a dichotomy of disordered versus healthy people, namely subjects fulfill a sufficient number of polythetic diagnostic disorder classification criteria or they do not (Kendler and Parnas, 2015; Krueger and Markon, 2006). Research suggests, however, that mental strengths and symptoms are generally continuously distributed in the population, without any evident “zone of rarity”, and that existing cutoffs are arbitrary and inconsistent (e.g. Gutiérrez et al., 2008; Kendell and Jablensky, 2003; Kendler, 2012; Ormel et al., 2013; Widiger and Sankis, 2000). Mental health problems that might require care can be located at the extreme ends of continuously distributed mental state dimensions (Clark and Watson, 1991; Durbin and Hicks, 2014; Krueger, 1999; Mineka et al., 1998). Although the dimensional approach to psychopathology regains influence in psychiatry (Dumont, 2010; Kendler, 2012; Kendler and Parnas, 2015), research into an empirical foundation remains imperative.

Second, the DSM defines mental health in terms of the presence or absence of symptoms, which is a rather narrow (and negative) view on the numerous psychological processes that define a person's mental state (Duckworth et al., 2005; Horwitz and Wakefield, 2007; Huber et al., 2011; Kendler, 2012; Sheldon et al., 2011; Whooley, 2014). Focusing solely on mental illness can, at best, reduce mental illness, but does not suffice for mental health (Keyes, 2007; Westerhof and Keyes, 2010). Mental health requires the absence of disease and disability (negative states), social and psychological well‐being (positive states), and abilities to adapt to one's environment and self‐manage (World Health Organization, 1946; Huber et al., 2011; Keyes, 2007; Solomon, 2014). More fundamentally, it is unlikely that we learn to understand the mechanisms underlying psychiatric symptomatology when we fail to take into account the role of mental strengths, resources, and contextual factors in the eventual (non)expression of mental health problems, such as humour, self‐acceptance, hope, social participation, and social support (Duckworth et al., 2005; Keyes, 2007; Larson, 1999; Luthar et al., 2000; Seery et al., 2010; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Sheldon et al., 2011; Westerhof and Keyes, 2010).

Third, while some DSM criteria already specify variability between and within individuals, such as having symptoms “most of the day, nearly every day” versus “most days”, these specifications lack a solid empirical foundation, and do not allow for the identification of course fluctuations (Horwitz and Wakefield, 2007; Hyman, 2007; Kapur et al., 2012; Kupfer et al., 2002; Wardenaar and de Jonge, 2013; Widiger and Samuel, 2005), or for sequential expressions, such as a shift from sadness to anxiety over time (Doré et al., 2015; Kessler et al., 2005; Stossel, 2013). While DSM categories are presented as homogenous disease entities, combinations of symptoms prevail (co‐morbidity), while the boundaries between diagnostic categories are necessarily fuzzy (Clark et al., 1995; Kendler, 2012, Krueger and Markon, 2006; Ormel et al., 2013; Widiger and Samuel, 2005; 2008). Additionally, treatment effects tend to be rather non‐specific (Roest et al., 2015), and even genetic predispositions defy DSM syndrome boundaries in twin (Kendler, 1996), family (Dean et al., 2010), and genome‐wide association studies (Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2015).

Taken together, as long as the DSM is unable to take the dynamic interactions between mental symptoms, strengths, and contextual factors into account, and lacks an empirically based identification of between and within individual variation, our research on the classification of mental disorders remains unrealistic. This may help explain why research into disease mechanisms is stagnant and difficult to replicate.

The current project

The research project HowNutsAreTheDutch (Dutch: HoeGekIsNL) is designed to allow for the investigation of mental health as a dimensional and dynamic phenomenon, characterized by both vulnerabilities and strengths. HowNutsAreTheDutch (henceforth HND) is a widely broadcasted national crowdsourcing study in the Netherlands collecting self‐report data on mental health in a general population sample. The project uses an internet platform to recruit participants and invite them to assess themselves on multiple mental health dimensions. The combination of a cross‐sectional and intensive longitudinal diary design allows for a data‐driven empirical approach that may help us generate new ideas about how key variables interact in a multidimensional representation of individuals' mental condition. The primary purpose of HND is to explore the associations and dynamic interactions between mental strengths and vulnerabilities, both between and within participants. This paper presents the objectives, methods, and technology of both the cross‐sectional and longitudinal part of the HND study, and provides an overview of the sample's characteristics in terms of demographics, psychometrics, and missing data.

Methods

Crowdsourcing procedure

For HND we applied a crowdsourcing procedure, an important model for doing psychological research in which a task is outsourced to a group of people, often online, in an open call (Brabham, 2008; Howe, 2006). Previous health research studies have used crowdsourcing as a method to collect new information, and showed that it can be a useful method to obtain information that otherwise tends to be overlooked by researchers (e.g. Bevelander et al., 2014), or to collect big datasets on multiple outcomes that could not be realized without the participation of a large crowd (e.g. Revelle et al., 2010).

The crowdsourcing method enables for the development of “citizen science”, in which the general public volunteers to assist scientists in their research activities and contribute with their intellectual effort, knowledge, or tools and resources to answer real‐world questions (Hand, 2010). We hope that the HND crowdsourcing approach (a) engages Dutch inhabitants with the debate about psychiatric classification (Dehue, 2014) and (b) results in a sizeable sample of participants that allows for data‐driven analyses of the relations between mental symptoms and strengths both within and between individuals.

With HND we launched an open call to inhabitants of the Netherlands to join our research, and invited them to visit the Dutch website http://www.HoeGekIs.nl (also http://www.HowNutsAreTheDutch.com), which has been online since 19 December 2013. The open call was announced on local and national radio broadcasts, television, during local podium discussions, in newspapers, and in magazines. The news about the HND research project was picked up and further disseminated via online blogs, twitter, and other social media.

To join the project, participants had to register and create an account. Participants filled out their email address and a password on http://www.HoeGekIs.nl and received an email with a hyperlink to confirm their account. Before starting the actual research, participants were asked to provide information about their gender, birth year and month, their postal code area, and country of residence (the Netherlands/Belgium/Other). Although HND is targeted on Dutch citizens, we added a question about country of residence after news about HND was picked up by the Belgium media and Dutch speaking participants from Belgium started to join the website.

Two studies

The HND website comprises a cross‐sectional study and a longitudinal study with intensive repeated assessments in daily life, namely a diary study with ecological momentary assessments (EMA, see Bolger et al., 2003). Participants could complete either one of these studies, or both.

Cross‐sectional study

Procedure and questionnaires

The cross‐sectional study was launched together with the website on 19 December 2013. In this study participants were invited to complete various questionnaire “modules”, that is, a questionnaire or a set of combined questionnaires covering a specific domain (see Table 1). The order in which the modules could be completed was partly fixed. All questionnaire modules were visible from the start, but initially only part of them was activated. The first mandatory module was the “Start” module, assessing participants' socio‐demographic profile. Subsequently, participants got access to three key modules; (i) (an extensive assessment of one's) Living situation; (ii) Affect/mood; (iii) Well‐being, which could be completed in any order. After the Affect/mood and Well‐being modules had been completed all other modules became available and could be completed in any order. These latter modules were not yet available at the launch of the HND website, but were added to the website one at a time over the year following the launch. Every three months participants were informed about these additions via an email newsletter. All implemented are outlined in Table 1. Eligible participants were aged 18 or older and consented to their data being used for research.

Table 1.

Modules, instruments, and contents of the cross‐sectional study

| Module | Instrument | Description | Items | Response range | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Gender, birth year, postal code area, relationship status, number of children, education level, and occupational situation. | 8 | |||

| Living situation (socio‐demography) | Country of origin (also for both parents), family income, living arrangement, family members, pets, religion, time spent on television/internet/sports, length and weight, and hand preference. | 17 | |||

| Affect/mood | PANAS | PANAS Flemish version, assesses 10 positive and 10 negative emotions over the past week. | 20 | 1–5 | Peeters et al., 1996; Raes et al., 2009 |

| QIDS | The QIDS assesses and classifies DSM major depression with nine domains, sad mood, concentration, self‐criticism, suicidal ideation, interest, energy/fatigue, sleep, change in appetite/weight, psychomotor, over the past week. | 16 | 0–3 | ||

| DASS | The DASS measures mood over the past week and is sensitive to subthreshold symptoms. | 42 | 0–3 | Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995a, 1995b | |

|

De Beurs et al., 2001 |

|||||

| Well‐being | MANSA | The MANSA measures quality of life on multiple domains, with 12 items for a sum score, and four additional yes/no items. | 16 | 1–7 | Priebe et al., 1999 |

|

Priebe et al., 2010 |

|||||

| Happiness index | The Happiness index assesses the degree to which one judges the quality of one's life in a single item: Do you feel happy in general? | 1 | 0–10 | Fordyce, 1988; Veenhoven, 1994; Abdel‐Khalek, 2006 | |

| SPF‐IL | The SPF‐IL measures the five universal primary goals affection, behavioural confirmation, status, comfort, and stimulation, which, according to SPF theory, underlay individual well‐being. | 15 | 0–3 |

Nieboer et al., 2005 |

|

| Ryff scales | The Ryff scales of psychological well‐being measure self‐acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. | 39 | 1–6 |

Van Dierendonck, 2004 |

|

| Personality | NEO‐FFI‐3 | The NEO‐FFI‐3 personality inventory assesses the Big Five personality domains Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness with 60 items. This instrument was extended with 36 neuroticism items from the NEO‐PI‐3 to derive all facet traits for the neuroticism domain. | 96 | 1–5 |

De Fruyt and Hoekstra, 2014 |

| Dark Triad | The Dark Triad assesses tendencies towards Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. | 12 | 1–9 | Paulhus and Williams, 2002, Klimstra et al., 2014 | |

| Doing, Feeling, Thinking | Doing, Feeling, Thinking assesses tendencies towards the behavioural styles Doing (practically‐oriented), Feeling (relation‐oriented), and Thinking (content‐logic‐oriented). | 9 | 1–3 |

De Klerk et al., 2003 |

|

| Somatic Symptoms | PHQ‐15 | The PHQ‐15 is a screening and diagnostic tool to assess somatic symptoms associated with mental health disorders. | 15 | 1–3 |

Kroenke et al., 2002 |

| RoSi | A composite of five items from the SCL somatic scale and eight items derived from an expert committee supervised by J. Rosmalen. | 13 | 0–2 | Arrindell and Ettema, 1986 (SCL) | |

| Whiteley Index | The Whiteley index measures tendencies towards hypochondria. | 14 | 0–1 |

Speckens et al., 1996 |

|

| Psychotic Experiences | CAPE | The CAPE measures positive and negative symptoms of psychosis with 42 items. We only selected the 34 items about psychotic symptoms and skipped the depression items. | 34 | 0–3 |

Konings et al., 2006 |

| Humour | HSQ | The HSQ assesses affiliative, self‐enhancing, aggressive, and self‐defeating humour styles. | 32 | 1–7 |

Martin et al., 2003 |

| Optimism | LOT‐R | The LOT‐R assesses dispositional optimism (and pessimism). | 10 | 0–4 |

Glaesmer et al., 2012 |

| Empathy | EQ | The EQ questionnaire measures both affective empathy via shared emotions and cognitive empathy or theory of mind. | 40 | 0–2 |

Baron‐Cohen and Wheelwright, 2004 |

| Childhood adversity | CTQ‐SF | The CTQ‐SF is a retrospective self‐report questionnaire designed to assess five dimensions of childhood maltreatment: physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. | 28 | 1–5 |

Thombs et al., 2009 |

| Intelligence | ICAR | We selected 11 items measuring inductive reasoning and 24 items measuring three‐dimensional (3D) rotation abilities from the ICAR cognitive item pool. | 35 | 1–6 1–8 |

Condon and Revelle, 2014 |

| Evaluation | Evaluation | The evaluation questionnaire was designed to evaluate the HND website, the cross‐sectional questionnaire modules, the feedback upon completed modules, and the impact of participation. | 7 | 1–10 |

Note: CAPE = Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences; CTQ‐SF = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EQ = Empathy Quotient; HND = HowNutsAreTheDutch; HSQ = Humour Styles Questionnaire; ICAR = International Cognitive Ability Resource Base; LOT‐R = Life Orientation Test – Revised; MANSA = The Manchester Short Assessment of quality of life; NEO‐FFI‐3 = The Neuroticism–Extraversion–Openness Five‐Factor Inventory updated and revised version; PANAS = Positive And Negative Affect Schedule; PHQ‐15 = The Patient Health Questionnaire 15 item version; SCL = Symptom Checklist; SPF = Social Production Functions; SPF‐IL = The SPF Instrument for the Level of well‐being; QIDS = The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; RoSi = Rosmalen Somatic items scale.

Feedback generation

After completing a questionnaire module participants received instant and automated feedback on the website. This feedback consisted of bars showing their scores relative to the maximum possible score on a given questionnaire and bars or spider plots reflecting their personal scores relative to the average scores of the HND participants. Examples are presented in Figures S1–S3 in the Supplementary Material.

Diary study

Procedure

The diary study was launched on 22 May 2014. In this study participants were intensively monitored in their natural environments by means of electronic diaries, three times a day for 30 days, resulting in a maximum of 90 assessments per individual. Assessments were prompted at equidistant time points with a six‐hour interval in between, with the exact time points depending on participants' sleep–wake schedule. Participants received a text message on their mobile phone with a link to a questionnaire. They were asked to fill out the questionnaire immediately after the alert, or, if impossible, within one hour, after which the questionnaire could no longer be accessed. Participants were informed about the requirements and procedure of the diary study by means of an information page and a short animated movie clip on the HND website. Additionally, they could download an information booklet with details on the study procedure, diary items, and their reward, being a digital report containing personalized feedback.

The study requirements were: age 18 or above, having a mobile phone with internet connection, not engaged in shift work, not anticipating a major disruption of daily routines (e.g. a planned trip abroad, an anticipated surgical operation), being aware that participation would be useless in case too many assessments would be missed, and approving of one's anonymous data being used for scientific research. Participants had to check a box for each of these requirements before they could proceed. Subsequently, they had to complete a baseline assessment consisting of the items of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS; Peeters et al., 1996; Raes et al., 2009), the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS; Rush et al., 2003, 2006), and two extra items retrieved from the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS; Rush et al., 1996) to assess anxiety/panic symptoms. Finally, participants configured their personal settings for the daily assessments, i.e. their telephone number, their preferred start date (within five days after completion of the baseline assessment), and the sampling schedule. Participants were instructed to pick a sampling schedule that fitted their daily rhythm, with the evening measurement preferably half an hour before their regular bedtime.

After completion of their diary study, participants were sent a short evaluation questionnaire. Participants who quit the study prematurely were asked for their reasons to quit by means of a short questionnaire.

Questionnaire items

The diary questionnaire contained 43 items. It combined items from existing and validated questionnaires and a few newly created items. We assessed subjective well‐being, sleep, mood, anxiety, depression, physical activity, physical discomfort, self‐esteem, worrying, loneliness, mindfulness, context (location, social company, activities), and the appraisal of this context, stressful events, time pressure, the feeling one makes a difference, laughing, and being outdoors. All questionnaire items and literature references are presented in Table 2. Additionally, participants could define a personal item that they felt relevant to their situation. This item could be chosen from a list of options or could be self‐created during the configuration of personal settings. Examples of personal items were: “I worry a lot” or “I smoked a lot since the last assessment”. All items except categorical ones were rated on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100, with appropriate labels at the extremes and middle of the scale, and the middle as default positive. To answer a question the slider had to be moved.

Table 2.

Items of the diary study

| Question | Dutch | Translation | Response range | Range | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hoe gaat het op dit moment met u? | How are you doing right now? | “Very bad” to “Very good” | 0–100 | Moment‐to‐moment quality of life | |

| 2. | Heeft u sinds het vorige meetmoment geslapen? | Did you sleep since the last measurement? | (1) No | 1–2 | Sleep (check boxes). If yes, go to 3–4. | |

| (2) Yes | ||||||

| 3. | Heeft u goed geslapen? | Did you sleep well? | “Not at all” to “Very well” | 0–100 | Quality of sleep | |

| 4. | Heeft u lang genoeg geslapen? | Did you sleep long enough? | “Too short” to “Too long” | 0–100 | Duration of sleep | |

| 5. | Ik voel me ontspannen | I feel relaxed | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Deactivation | |

| 6. | Ik voel me somber | I feel gloomy | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Deactivation | |

| 7. | Ik voel me energiek | I feel energetic | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Activation | |

| 8. | Ik voel me angstig | I feel anxious | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Activation | |

| 9. | Ik voel me enthousiast | I feel enthusiastic | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Activation | |

| 10. | Ik voel me onrustig | I feel nervous | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Activation | |

| 11. | Ik voel me tevreden | I feel content | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Deactivation | |

| 12. | Ik voel me prikkelbaar | I feel irritable | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Activation | |

| 13. | Ik voel me kalm | I feel calm | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Deactivation | |

| 14. | Ik voel me lusteloos | I feel dull | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Deactivation | |

| 15. | Ik voel me opgewekt | I feel cheerful | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Positive affect Activation | |

| 16. | Ik voel me moe | I feel tired | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Negative affect Deactivation | |

| 17. | Ik ervaar lichamelijk ongemak | I experience physical discomfort | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Somatic symptoms | |

| 18. | Ik voel me gewaardeerd | I feel valued | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Self‐esteem | |

| 19. | Ik voel me eenzaam | I feel lonely | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Loneliness | |

| 20. | Ik heb het gevoel tekort te schieten | I feel I fall short | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Worthlessness | |

| 21. | Ik voel me zelfverzekerd | I feel confident | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Self‐esteem | |

| 22. | Ik pieker veel | I worry a lot | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Worrying | |

| 23. | Ik ben snel afgeleid | I am easily distracted | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Concentration/mindfulness | |

| 24. | Ik vind mijn leven de moeite waard | I feel my life is worth living | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Worthlessness/suicidal ideation | |

| 25. | Ik ben van slag | I am unbalanced | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Stress reactivity | |

| 26. | Ik leef in het hier en nu | I am in the here and now | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Mindfulness | |

| 27. | Mijn eetlust is | My appetite is | “Much smaller than usual” to “Much larger than usual” | 0–100 | Appetite | |

| 28. | Hoe druk heb ik het? | How busy am I? | (1) Much too busy | 1–5 | Time pressure | |

| (2) Pleasantly busy | ||||||

| (3) Neutral | ||||||

| (4) Pleasantly quiet | ||||||

| (5) Much too quiet | ||||||

| 29. | Waar was ik het afgelopen dagdeel de meeste tijd? | Where have I spent most of my time since the last measurement? | (1) At home | 1–9 | Location (check boxes; only one location could be checked) | |

| (2) At work/school | ||||||

| (3) With family/friends | ||||||

| (4) On the way | ||||||

| (5) Vacation home/hotel/camping | ||||||

| (6) Hospital/health facility | ||||||

| (7) Restaurant/beanery | ||||||

| (8) In nature | ||||||

| (9) Somewhere else | ||||||

| 30. | Wat deed ik het afgelopen dagdeel de meeste tijd? | How did I spend most of my time since the last measurement? | (1) Resting/sleeping | 1–13 | Activities (check boxes; only one activity could be checked) | |

| (2) Household/groceries | ||||||

| (3) Working/studying/ volunteering | ||||||

| (4) Exercising/walking/cycling | ||||||

| (5) Yoga/meditation/ sauna visit etc. | ||||||

| (6) Reading | ||||||

| (7) Hobby (e.g. gardening, making music) | ||||||

| (8) Trip (e.g. leisure park, concert) | ||||||

| (9) Watching tv | ||||||

| (10) Websurfing/ gaming/ social media | ||||||

| (11) Conversing | ||||||

| (12) Something intimate (e.g. Cuddling, sex) | ||||||

| (13) Something else/ all kinds of things | ||||||

| 31. | Ik ervoer deze activiteit overwegend als | I experienced this activity mainly as | “Very unpleasant”, via “Neutral”, to “Very pleasant” | 0–100 | Appraisal of activity | |

| 32. | Is er het afgelopen dagdeel iets bijzonders gebeurd? | Did something special happen since the last measurement? | (1) No, nothing | 1–4 | Special event (check boxes; only one box could be checked). If nothing, jump to 34, otherwise 33. | |

| (2) Yes, something positive | ||||||

| (3) Yes, something neutral | ||||||

| (4) Yes, something negative | ||||||

| 33. | Waar had dit mee te maken? | This was related to | (1) Myself | 1–7 | Context of special event (check boxes; only one box could be checked). | |

| (2) Home situation/ close family/ significant others | ||||||

| (3) Friends/ other family/ acquaintances | ||||||

| (4) Work/ school | ||||||

| (5) Society/ news | ||||||

| (6) Public space/ strangers | ||||||

| (7) Other | ||||||

| 34. | Ik was het afgelopen dagdeel grotendeels | Most of the time since the last measurement I was | (1) Alone | 1–2 | Social company (check boxes; only one box could be checked). If alone, go to 35, followed by 38. If in company, go to 36–37. | |

| (2) In company | ||||||

| 35. | Ik was liever in gezelschap geweest | I would rather have been with others | “No, preferably not” to “Yes, certainly” | 0–100 | Appraisal of being alone | |

| 36. | Ik zou liever alleen zijn geweest | I would rather have been alone | “No, preferably not” to “Yes, certainly” | 0–100 | Appraisal of social company | |

| 37. | Ik vond dit gezelschap overwegend | I found my company predominantly | “Very unpleasant”, via “Neutral”, to “Very pleasant” | 0–100 | Appraisal of social company | |

| 38. | Ik heb in het afgelopen dagdeel gelachen | Since the last measurement I had a laugh | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Laughing | |

| 39. | Ik heb in het afgelopen dagdeel iets voor iemand kunnen betekenen | Since the last measurement I was able to make a difference | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Making a difference | |

| 40. | Ik ben het afgelopen dagdeel buiten geweest | Since the last measurement I have been outdoors | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Being outside | |

| 41. | Hoe lichamelijk actief was ik het afgelopen dagdeel? | Since the last measurement I was physically active | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Physical activity | |

| 42. | Ik deed dingen “op de automatische piloot”, zonder me bewust te zijn van wat ik deed | I did jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I was doing | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Mindfulness | |

| 43. | Mijn eigen belangrijke factor | My personal important factor | “Not at all” to “Very much” | 0–100 | Personal item |

Note: Momentary affect and anxiety were assessed with 12 items from the circumplex model of affect, which describes affect in terms of two dimensions: valence and activation (items 5–16; Barrett and Russell, 1998; Yik et al., 1999). Sleep was assessed with one item from the Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (Monk et al., 1994) and two self‐constructed items (items 2–4). We added four extra items reflecting the DSM‐V criteria for depression not already covered by the affect and sleep items, which we derived from the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (Wittkampf et al., 2009) and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (Rush et al., 1996), and adapted for daily use (items 20, 23, 24, 27). Subjective well‐being was assessed with a single item reflecting moment‐to‐moment quality of life (item 1: Barge‐Schaapveld et al., 1999). Self‐esteem, worrying, loneliness, physical activity, physical discomfort, context (location, social company, activities), and the appraisal of this context were assessed with items adapted from previous ecological momentary assessment studies (items 17–19, 21, 22, 29–31, 34–37, 42: Barge‐Schaapveld et al., 1999; Collip et al., 2011; Csikszentmihalyi and Larson, 1987; Doane and Adam, 2010; Myin‐Germeys et al., 2009; Savin‐Williams and Demo, 1983; Wichers et al., 2011). Mindfulness was assessed with two items adapted from the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al., 2006, 2008) and one self‐constructed item (items 23, 26, 42). We added seven self‐constructed items to assess stressful events, time pressure, making a difference, laughing, and being outside (items 25, 28, 32, 33, 38, 39, 40). Participants could also define a personal item that they felt relevant to their situation (item 43; see Methods section).

Feedback generation

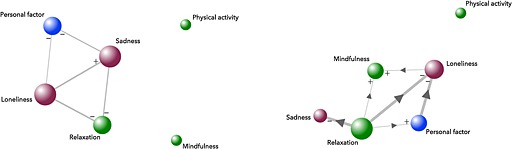

After completion of the study participants received instant and automated feedback on the website. Participants who completed at least 65% (t ≥ 59) of the assessments received basic personalized feedback consisting of graphs and explanatory text (see Figures S4–S7 in the Supplementary Material). Participants who completed at least 75% (t ≥ 68) of the assessments also received personal network models showing the interrelationships between variables assessed in the diary study, see Figure 1 for an example network. The first network model depicts the concurrent relationships between variables. This model shows how a participant's affect, cognitions, and behaviours are related to each other at the same moment in time. The second network model shows the dynamic, directed relationships between variables, indicating how they affected each other over time.

Figure 1.

Example of a personal network model showing concurrent (left) and dynamic relationships (right) between diary items. Note: Red nodes represent variables that tend to be perceived as negative (e.g. loneliness, sadness). Green nodes represent variables that tend to be perceived as positive (e.g. relaxation, mindfulness, feeling cheerful). The blue node represents the personal variable that participants could choose to add to the diary assessment. This variable could either be “negative” or “positive” and could be different for each participant. The size of the node indicates its relative importance (i.e. the bigger a node, the more connections the variable has with other variables). The lines represent the connections between variables; the thickness indicates the strength of the relationship. A plus refers to a positive relationship; a minus refers to a negative relationship. The arrowheads (only in the dynamic networks) indicate the direction of the relationships.

The network models were estimated for each participant separately using vector autoregressive (VAR) modelling (Brandt and Williams, 2007; Lütkepohl, 2006). To automate this procedure, we used Autovar, an open source R package that reads raw data and automatically fits and evaluates VAR models (Blaauw et al., 2014; Emerencia et al., 2015, Van der Krieke et al., 2015. The number of variables included in the network models was limited to six, for the sake of comprehension and in order to focus on the most informative results. These six variables were selected based on highest moment‐to‐moment variability (as indicated by the mean squared successive difference, MSSD) and lowest skewness. Both variables usually perceived as “positive” (e.g. laughing, relaxation) and variables perceived as “negative” (e.g. rumination, feeling down) were selected, as well as the participant's personal item, unless variability was too low (MSSD < 50) or skewness too high (z‐skewness > 4). Only VAR models with one time lag were estimated, to prevent over‐parameterization. Dummy variables for the part of the day (morning/afternoon/evening) were included in all models. Trend variables denoting the assessment point (and the square of it) were included if necessary. Dummy variables for the days of the week were included and variables were log transformed if this improved model fit. Autovar only considered models that met the assumptions of stability, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence, and selected the best model based on the Akaike Information Criterion. Details on the procedure for automated network models are available from the authors upon request.

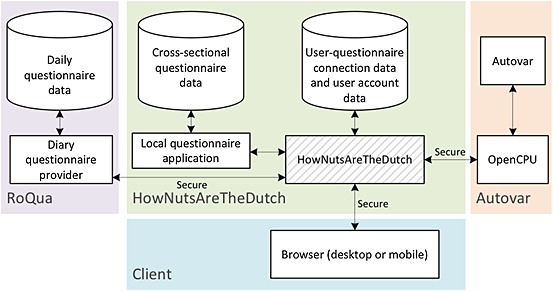

Technological infrastructure of HowNutsAreTheDutch (HND)

An architectural overview of the HND web application, the external services involved, and the security of the connections is presented in Figure 2. The figure shows that HND consists of three main components. The first component is the HND application itself. This application is implemented in the Ruby on Rails framework (http://rubyonrails.com). The data is stored in two databases. The personal socio‐demographic data (i.e. gender, birth month, birth year, and postal code area) are stored in a PostgreSQL database (http://postgresql.org). The other questionnaire data are stored in a MongoDB database (http://mongodb.com). The use of two separate databases lowers the impact of a potential database security breach. Both databases would have to be compromised to trace questionnaire data back to potentially identifying personal information. All web traffic to and from HND is encrypted using a 128bit TLS/2048bit RSA Secure Socket Layer (SSL) certificate. This SSL certificate ensures that any data exchanged between participants and the HND website application is unreadable for anyone else. The HND component in Figure 2 serves the web application to the clients, contains the registration and login services, provides the cross‐sectional questionnaires and provides the feedback. This component also interfaces to the other two components; the RoQua service and the Autovar service.

Figure 2.

Architectural overview of the HowNutsAreTheDutch (HND) web application. Note: The cylindrical shapes represent databases. The rectangular shapes depict (web) services. The hatched rectangle is the actual HND web application that serves the website.

RoQua is a Software as a Service (SAAS) product that offers scheduling of momentary assessments and collection of questionnaire data (http://roqua.nl). HND communicates with RoQua in order to schedule the measurement for each participant. When a participant is scheduled to fill out a questionnaire, RoQua notifies HND. HND then notifies the participants and redirects them to the RoQua service, which conducts the questionnaire and stores the result.

The Autovar service is a statistical service used to analyse the diary questionnaire data (http://autovar.nl). In order to expose Autovar's functions to the HND platform, Autovar uses a service known as OpenCPU (Ooms, 2014). OpenCPU offers a RESTful (REpresentational State Transfer) interface that allows R functions to be used by other systems and programming languages.

Ethics

The HND study protocol was assessed by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Centre Groningen. The committee judged the protocol to be exempted from review by the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (in Dutch: WMO) because it concerned a non‐randomized open study targeted at anonymous volunteers in the general public (registration number M13.147422 and M14.160855).

Sample comparisons

One has to realize that particular individuals are less likely to participate in crowdsourcing studies. To explore selection effects we compared the characteristics of the HND sample with (a) the general Dutch population according to the Dutch Governmental Agency for Statistics (CBS) and (b) two representative samples from the non‐institutionalized Dutch population, that is, the Netherlands Mental Health Survey (NEMESIS‐2, n = 6646, 2007–2009, see de Graaf et al., 2010) and the Lifelines population study from the north of the Netherlands (n = 167,729, 2006–2013, see Scholtens et al., 2014).

Results

Cross‐sectional study

Sample characteristics

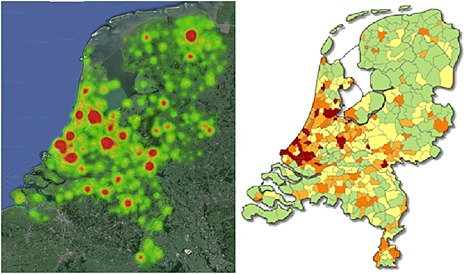

Up to 13 December 2014 12,734 participants participated in the cross‐sectional study. We excluded 231 participants from our analyses because they were younger than 18 (n = 228) or provided unrealistic entries (e.g. birth year < 1900; n = 3), resulting in a final sample of 12,503. The mean age of the participants was 45 years [standard deviation (SD) = 15] and 65% were women. A detailed overview of the participants is given in Table 3. Participants were sampled from all regions of the Netherlands, as illustrated by the heat map of the Netherlands in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the cross‐sectional HowNutsAreTheDutch (HND) sample

| Module | Topic | N | Range | Raw descriptives | Weighted descriptivesa | SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | SD | Nb | Mean | SEc | |||||

| Start | Age | 12,503 | 18 to 90d | 45.3 | 0.13 | 14.6 | 12,189 | 40.7 | 0.17 | 13.7 |

| Education level | 12,189 | 1 to 8e | 6.9 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 12,189 | 6.4 | 0.02 | 1.5 | |

| Duration of romantic relationship in years | 9,038 | 1 to 80 | 18.3 | 0.14 | 13.7 | 9,038 | 14.7 | 0.18 | 12.6 | |

| Living situation (socio‐demography) | Number of children | 12,190 | 0 to 12 | 1.2 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 12,189 | 1.1 | 0.01 | 1.2 |

| Height in centimetresf | 11,035 | 100 to 213 | 174.7 | 0.09 | 9.1 | 11,034 | 175.1 | 0.12 | 9.1 | |

| Weight in kilogramsf | 11,034 | 20 to 190 | 74.6 | 0.14 | 14.7 | 11,034 | 74.7 | 0.20 | 15.2 | |

| Affect/ Mood | PANAS Positive affect | 8,031 | 10 to 50 | 34.2 | 0.08 | 6.9 | 8,030 | 33.5 | 0.11 | 7.1 |

| PANAS Negative affect | 8,032 | 10 to 50 | 19.7 | 0.08 | 7.2 | 8,030 | 20.5 | 0.12 | 7.4 | |

| DASS Depression | 7,972 | 0 to 42 | 6.8 | 0.09 | 7.8 | 7,972 | 7.3 | 0.13 | 8.2 | |

| DASS Anxiety | 7,972 | 0 to 42 | 3.6 | 0.06 | 4.9 | 7,972 | 4.0 | 0.09 | 5.4 | |

| DASS Distress | 7,973 | 0 to 42 | 8.6 | 0.08 | 7.0 | 7,972 | 9.4 | 0.12 | 7.3 | |

| Well‐being | MANSA quality of life | 10,181 | 12 to 84 | 62.1 | 0.09 | 8.6 | 10,180 | 61.4 | 0.13 | 9.0 |

| Happiness index | 10,152 | 0 to 10 | 6.9 | 0.02 | 1.6 | 10,151 | 6.8 | 0.02 | 1.7 | |

| SPF‐IL | 10,131 | 0 to 45 | 25.1 | 0.06 | 5.9 | 10,130 | 24.4 | 0.08 | 5.9 | |

| Ryff total | 10,033 | 46 to 234 | 166.6 | 0.27 | 26.6 | 10,133 | 163.7 | 0.38 | 27.4 | |

Note: DASS = Depression‐Anxiety‐Stress Scale; MANSA = The Manchester Short Assessment of quality of life; PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; SPF‐IL = The Social Production Function Instrument for the Level of well‐being.

The calculation of the post‐stratification weights can be found in Supplementary Material Table S2.

The N for the weighted descriptives (N = 12,189) is smaller than for the raw descriptives because 314 participants (2.5%) did not provide their education level correctly.

Standard errors based on Taylor series linearization in R‐package “svy” (Lumley, 2014).

The distribution of age and gender is presented visually in Figure S8 in the Supplementary Material.

Education level ranged from one (elementary school not finished) to eight (academic degree).

The lower thresholds of the height and weight range seem rather extreme, but only four individuals reported a height below 150 cm (<0.1%), and two people scored their weight below 35 kg, and seven below 40 kg (0.1%).

Figure 3.

Heat map of the cross‐sectional study participants' residence versus population density map. Note: The population density map on the right is derived from CBS statline and presents Dutch population densities per municipality in 2010 in terms of number of inhabitants per square kilometre: From low in green (21–250), via yellow (250–500) and orange (light: 500–1000, dark: 1000–2500) to red (2500–6000). The pictures show that the study coverage concurs very well with population density scores.

The coverage concurs very well with population density scores. However, compared to the Dutch population, the HND participants were more often women (65.2% versus 50.5% in the population, NEMESIS = 55.2%, Lifelines = 57.9%), on average slightly older (45 versus 39 years; NEMESIS = 44, Lifelines = 42), more often with a romantic partner (74% versus 58%), with whom they cohabited more often (61% versus 47%; NEMESIS = 68%). Most saliently, HND sampled few people from lower educated strata (2% versus 22%; NEMESIS = 5%), as well as medium education levels (16 years and more, 22% versus 43%; NEMESIS = 60%); HND participants tend to be higher educated (>20 years, 76% versus 35%; NEMESIS = 35%). Elderly were relatively well sampled in HND, as most participants were older than 45 (55%), and 9% of them were older than 65 (versus 19% of the population; Lifelines = 7.6%, NEMESIS did not include participants older than 64). To enable comparisons between this HND sample and population samples, and to perform robustness checks for our models, we calculated a selection bias weight factor, based on population proportions derived from the CBS. Post‐stratification weights were derived for 36 strata based on age (six categories), gender, and education level (three categories), see Supplementary Material Table S1. Our weighted results are presented in Table 3.

Key results

Exactly 62,068 questionnaire modules were completed, on average five modules per participant (12,402 participants filled out ≥ 1 of the 14 available questionnaires). The key questionnaire modules focusing on Affect/mood and Well‐being were completed approximately 8000 and 10,000 times, respectively (see Supplementary Material Table S2), while 5144 participants filled out all three key modules (including life situation). All modules were completed by 627 participants (except intelligence, which was only available in the last three weeks).

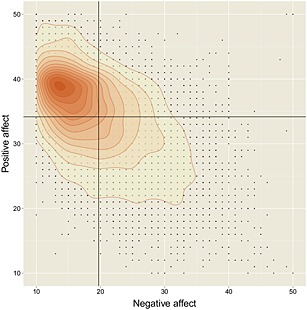

As presented in Table 3, on average participants reported more positive than negative affect (PANAS, mean = 34 versus 20, respectively, both SD = 7 and range 10–50). However, both the positive affect and the negative affect scales showed high variance. A visual representation of the relationship between positive and negative affect in Figure 4 indicates that participants with a similar score on negative affect varied substantially in their positive affect scores, and the other way around, despite their strong correlation (r = −0.52, p < 0.001). Albeit women reported slightly more negative (t = 8.25, p < 0.001, d = 0.19) and less positive affect than men (t = 4.54, p < 0.001, d = 0.11) gender differences were minimal (see Supplementary Material Table S3).

Figure 4.

Positive and negative affect in the cross‐sectional sample. A scatterplot with scores of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The black lines in the figure indicate the mean values for positive affect (34.3) and negative affect (19.7). The darker the orange the higher the number of people with that specific score. The black dots represent actual observations.

Regarding mood, the Depression–Anxiety–Stress Scale (DASS) showed that symptoms of psychological stress were most common, followed by symptoms of depression and anxiety. The large standard deviations and broad ranges of these scales indicate that substantial heterogeneity exists among participants. Based on DASS cutoff values (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995b), 14.8% of the participants in our sample reported mild, 9.1% moderate, 3.9% severe, and 1.3% extremely severe depression symptom levels (in the past week). With respect to anxiety, 15.1% scored mild, 11.0% moderate, 4.6% severe, and 1.9% extremely severe. With respect to psychological stress, 17.9% scored mild, 9.5% moderate, 2.7% severe, and 0.4% extremely severe.

There was considerable overlap between individuals with severe levels on the three subscales: all individuals who had severe symptom levels of stress and depression also had severe symptom levels of anxiety. Gender differences were small (see Supplementary Material Table S3), with women reporting slightly more symptoms of stress (t = 9.89, p < 0.001, d = 0.23), anxiety (t = 7.93, p < 0.001, d = 0.18), and depression than men (t = 2.64, p < 0.01, d = 0.06). Finally, there were also many participants without a single symptom of anxiety (26.6%), depression (16.8%), or psychological stress (6.7%).

Most participants rated their quality of life fairly high (as measured with the Manchester Short Assessment of quality of life (MANSA), mean = 62, range 12–84). In terms of happiness the average rating was 6.9 on a scale from 0 to 10 (SD = 1.6, n = 10,152, median = 7.0. About 85% of the participants rated their happiness a six or higher, and 40% an eight or higher). Results of the Ryff total scale (range 46–234) indicate substantial individual differences in subjective well‐being. On average, women reported slightly lower well‐being than men (t = −3.52, p < 0.001, d = 0.08), mainly due to less self‐acceptance (t = −4.59, p < 0.001, d = 0.10) and lower autonomy (t = −21.77, p < 0.001, d = 0.44). However, compared to men, women reported more positive social relationships (t = 10.05, p < 0.001, d = 0.21) and personal growth (t = 7.77, p < 0.001, d = 0.17). Finally, even the subgroup of severely depressed, anxious, or stressed participants (about the highest 5% scores on the DASS, n = 578) rated their well‐being fairly diverse (Ryff total score, range = 46–206, mean = 125, SD = 27, median = 123), just as their general happiness (range = 0–10, mean = 4.1, SD = 2.2, median = 4.0). Apparently, experiencing high symptom levels does not necessarily preclude enjoying life.

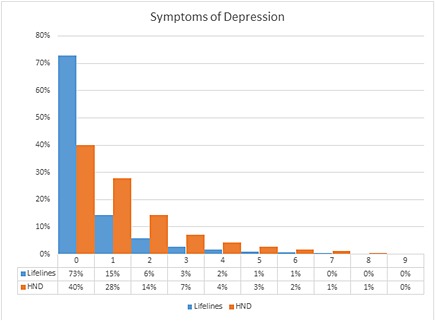

Finally, we weighted our results for the selection bias factor. The results in Table 3 suggest that mood symptoms are slightly underestimated in our sample, relative to the general Dutch population. Anxiety was more prevalent than depression/stress in both the HND and NEMESIS sample (4.6%, past week, HND; and 12.4%, past 12 months, NEMESIS). In the HND sample 3.9% reported severe depression (past week), while 5.8% of the NEMESIS participants reported a major depression in the past 12‐months. In Figure 5 we present the prevalence of the nine symptoms of depression according to the DSM in the HND sample and in the Lifelines sample, namely, depressed mood, diminished interest, weight loss/gain, insomnia/hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation/retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, worthlessness/guilt, concentration problems, and suicidal ideation. The HND participants reported more symptoms of depression (QIDS, self‐report, past week) than the Lifelines participants (MINI clinical interview, past year), but these differences dissipate at the higher total scores, in line with a lower threshold for self‐report and timing effects.

Figure 5.

The prevalence of the nine DSM depression symptoms. The prevalence for each number of depression symptoms in the HowNutsAreTheDuch (HND) sample and the Lifelines sample. The vertical axis shows the percentage of participants with this particular number of symptoms.

Diary study

Sample characteristics

Up to 13 December 2014 629 participants completed the diary study (5% of all HND participants). Of the diary participants 532 (85%) also filled out additional cross‐sectional modules. The 629 participants were 517 women (82%, mean age = 39, SD = 13) and 112 men (18%, mean age = 48, SD = 13), mainly Dutch (99%) and spread throughout the Netherlands; five participants were Belgian and one had another nationality. Diary study participants (n = 629) were on average 5.4 years younger than the other HND participants (t = 9.78, p < 0.001, d = 0.40), more often women (χ 2 = 84.51, p < 0.001, d = 0.28), higher educated (t = −5.67, p < 0.001, d = 0.24), and they reported lower well‐being (t = 3.23, p < 0.001, d = 0.14; see Supplementary Material Tables S4 and S5). Details on the diary study are presented elsewhere (Van der Krieke et al., submitted for publication).

Key results

Diary study participants completed 28,264 assessments in total, with 45 assessments on average per participant (range 0–90, SD = 32). Since analyses were run for each participant separately, group‐based results are not presented here. About 48% (n = 302) participants completed enough assessments (t ≥ 59) to receive basic feedback, and 38% (n = 238) completed enough assessments (t ≥ 68) to receive additional advanced feedback, including a concurrent and dynamic personal network model.

Evaluation of the website

The evaluation questionnaire was completed by 3093 participants who were on average 48 years old (SD = 14), and 65% were women. In the evaluation questionnaire participants scored six components of the cross‐sectional study of the HND website on a scale from 1 to 10. In short, the mean score for the lay‐out of the website was rated 7.6, the cross‐sectional modules 7.7, the presented results 7.3, and the overall judgement 7.7. The diary study was evaluated separately, and these results are presented elsewhere (Van der Krieke et al., submitted for publication).

Missing data

In HND we use digital questionnaires of which most are programmed such that they need to be completed from top to bottom and no items can be left blank. As a result, the missing data within questionnaires is minimal. In the cross‐sectional study many questionnaire modules were optional, so not all participants completed all modules. Supplementary Material Table S2 shows how many participants completed each module (range generally from 800 to 12,000). In the diary study, many participants missed assessments, as we expected. To present reliable network models, we only ran VAR analyses for participants who completed > 75% of the data (≥68 observations, n = 238). Missing data of these participants were imputed using Amelia‐II imputation (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Amelia/Amelia.pdf). Time series data with many missing observations are not suitable for time series analysis, but can be included in multilevel analyses and data‐mining procedures, which is what we intend to do in the future.

Comments

HND is primarily a scientific endeavour to explore ways in which the classification of psychiatric symptoms can be improved, via data‐driven studies of how mental vulnerabilities and strengths are related and interact, including humour, empathy, and self‐acceptance, and by zooming into dynamic interactions between health‐related variables. Additionally, we aspire to contribute to the debate about mental health in the Netherlands, aiming to reduce the stigma associated with psychiatric diagnosis (Hinshaw and Stier, 2008). An emphasis on the dimensional nature of mental health and attention for individuals' strengths may contribute to opportunities to increase mental health in people suffering from mental symptoms.

Nearly half of the population will meet current DSM criteria for a mental disorder at some time in their life, but this does not mean that they will all need treatment (Kessler et al., 2005). Health is best defined by the person (rather than by the doctor), according to his or her functional needs, which can be the meaning of “personalized medicine” (Lancet, 2009; Perkins, 2001). Doctors, then, are partners in delivering those needs. Diary approaches can play a role in this process of empowerment, as they enable for personalized models that can shed light on etiology and personal dynamics, as well as personalized solutions, and merit the perspective of health as people's ability to adapt to their environments and self‐manage (Duckworth et al., 2005; Huber et al., 2011; Solomon, 2014). Goals and criteria for “treatment success” often differ substantially between clinicians and their patients, which may explain part of the high drop‐out rates (25–60%) for most psychiatric interventions (Perkins, 2001; Tehrani et al., 1996).

Mental symptoms may also be seen as more than “defects to be corrected”, as individuals' differences may be their very strengths. For example, individuals with autism may be great scientists, mathematicians, or software testers (Mottron, 2011; Solomon, 2014), while anxious individuals may be rather creative, sensitive, and agreeable, thus perfect employees for social job tasks (George et al., 2002; Stossel, 2013). Antagonistic, mistrustful, uncooperative and rude people, in contrast, may be excellent drill sergeants or bill collectors (George and Jones, 2002, p. 50). Furthermore, genes underlying creativity also increase vulnerability for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Power et al., 2015). Everyone has both strengths and weaknesses, but which is which is a function of the context in which we live and grow (Darwin, 1859).

There can even be tension between identity and illness, as some “symptoms” can feel self‐congruent and come without biographical breaks (e.g. in most personality disorders and autistic people), while other symptoms seem to invade an identity (e.g. in schizophrenia), and even “harm” often has a normative component (Dehue, 2014; Gutiérrez et al., 2008; Solomon, 2014). A reconsideration of diversity and focus on individual strengths and resources that may compensate for – or buffer against – the expression of mental symptoms, may help people to preserve acceptable levels of mental well‐being despite the presence of psychopathology (Harkness and Luther, 2001; Sheldon et al., 2011; Solomon, 2014). This would fit in with a concept of mental health as a hybrid of absence of mental illness and the presence of well‐being and mental resources (Duckworth et al., 2005; Keyes, 2007).

In sum, our aim is to improve classification for research purposes, and one promising direction is a dimensional and dynamic approach that acknowledges the role of the interactions between mental symptoms and strengths (Duckworth et al., 2005). Although categorization may be helpful in clinical practice to reach treatment decisions, this procedure may be supplemented with a patient‐tailored treatment via the introduction of diary studies and personalized models (Van der Krieke et al., submitted for publication).

Planned analyses

Data analyses of the HND project will be centred around three sets of analyses. The first set of analyses will focus on identifying profiles of mental symptoms and strengths based on the cross‐sectional data. For example, a study of predictors for emotional and psychological well‐being across the lifespan (Jeronimus et al., submitted for publication), or of resources that enable people to preserve subjective well‐being despite severe mental symptoms (Bos et al., in preparation). The second set of analyses will zoom into the dynamic relationships between mood, cognitions, and behaviours at the individual level, for which the diary data will be used. To this end we will use time series analysis and multilevel analysis. A first study showed that prosocial behaviour and positive affect enhance one another in daily life, and may thereby maintain positive mental states (Snippe et al., submitted for publication). A third set of analyses will apply machine learning techniques to find predictors for happiness (Wanders et al., in preparation), and to integrate dimensional and categorical approaches in the identification of affective subtypes (Wardenaar et al., in preparation). Up to 1 July 2015, a total of 32 research proposals have been accepted by the HND scientific board.

Dissemination of study findings

Apart from publication in scientific journals, study findings are presented to our participants, via the HND website. As described earlier, all participants receive individual results via the website after completing a questionnaire module in the cross‐sectional study, and after completing the diary study. In addition, participants are informed about study results via a newsletter (three to four times a year). Study results are also communicated to the broader Dutch population via news articles, radio interviews, podium discussions, and presentations open to the general public.

Strengths and limitations of the HND project

One of the strengths of the HND project is that we involve the general public in mental health research and in the debate about how mental health should be conceptualized. The project website provides participants with the opportunity to gain insight into their mental health, whether or not by comparing their scores to scores of other participants. Moreover, the combination of (a) measuring mental symptoms and strengths and (b) our longitudinal time‐intensive design may allow for a more accurate and in‐depth description of the dynamics of mental health and ill‐health than most studies are able to provide (Duckworth et al., 2005; Keyes, 2007; Lamiell, 1998; Molenaar and Campbell, 2009; Piantadosi et al., 1988). This broad range of assessed mental strengths set HND apart from previous studies such as NEMESIS and Lifelines.

The most salient limitation of our project is the problem of representativeness (self‐selection bias), especially the overrepresentation of highly educated strata and women. To estimate the extent to which selection effects curved our results we weighted our sample against the proportions in the general Dutch population, and compared the HND sample with the NEMESIS‐2 and Lifelines studies. Results suggest that scores of HND participants are likely to deviate somewhat from population averages on several psychological characteristics (mainly those associated with differences in education), which might attenuate the generalizability of our results (just as in NEMESIS and Lifelines). For this reason NEMESIS weighted their results (de Graaf et al., 2010). Nevertheless, in the HND, NEMESIS, and the Netherlands Study of Anxiety and Stress (NESDA) anxiety was more prevalent than depression, and the small gender differences were even comparable in size (e.g. for anxiety in HND d = 0.18 and NESDA d = 0.11; for depression in HND d = 0.06 and NESDA d = 0.08, see Jeronimus et al., 2013).

A large random sample from the general Dutch population (without strong selection bias and non‐response) would require immense resources. Note that only 58.6% of the random sample for NEMESIS‐2 actually participated in that study (de Graaf et al., 2010). In Lifelines only 24.5% of the intended sample invited via their general practitioner participated, while two‐thirds of the assessed sample resulted from self‐selection via other means than the general practitioner (see Scholtens et al., 2014).

It also remains doubtful whether a random sample would have yielded knowledge about individual dynamics that would be more applicable, informative, or transferable (“generalizable”) at the personal level, see Molenaar and Campbell (2009). Exactly therefore we implemented our diary study. Moreover, we believe that the underlying faculties of the mind (Panksepp and Biven, 2012) as well as the structure in our data (Kendler and Parnas, 2015) will not be different in subsamples of the population. Selection effects may thus, at worst, bias prevalence estimates (average symptom counts), but we deem it unlikely that selection effects invalidate research into the associations and interactions between personal vulnerabilities and resources.

Self‐selection is not necessarily problematic, as previous crowdsourcing studies attracted more diverse participants than any other means of recruitment did (Gosling et al., 2004; Revelle et al., 2010; Skitka and Sargis, 2006). For example, HND sampled more participants above age 65 (9% versus 19% in the population) than Lifelines (7.6%) and NEMESIS, which excluded people older than 64. This may reflect that the Netherlands are among the countries with most and fastest internet connections per capita worldwide (90% of the households is connected).

Another limitation concerns the diary study. We allowed our diary participants to complete their questionnaire until one hour after the prompt. Methodologically, the presence of this time window may have biased the results. For instance, when participants received the prompt at a busy moment, they had the opportunity to postpone their response to a more quiet moment, in which different emotions were experienced and reported. However, our data indicated that most diary questionnaires were completed within 12 minutes after the prompt (mean = 18.0, SD = 15.7), thus this methodological bias is probably small.

Conclusion

The HND project has resulted in a rich dataset containing both cross‐sectional and intensive longitudinal data providing information about mental symptoms and strengths, and their dynamic interactions. The data is used to provide personalized feedback to participants about their mental health, to study profiles of mental symptoms and strengths, and to zoom into the fine‐grained level of dynamic relationships between variables over time.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests.

Supporting information

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The HowNutsAreTheDutch (HND) project is funded by a VICI grant (no. 91812607) received by Peter de Jonge from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO‐ZonMW) and by the University Medical Center Groningen Research Award 2013, also received by Peter de Jonge. Part of the HND project was realized in collaboration with the Espria Academy. Espria is a health care group in the Netherlands consisting of multiple companies targeted mainly at the elderly population. The authors want to thank all participants of HND for their participation and valuable contribution to this research project. The authors also thank the RoQua team, Inge ten Vaarwerk, Esther Hollander, Jasper van de Gronde, Joris Slaets, Ester Kuiper and Chantal Bosman for their contributions.

Krieke, L. V. D. , Jeronimus, B. F. , Blaauw, F. J. , Wanders, R. B. K. , Emerencia, A. C. , Schenk, H. M. , Vos, S. D. , Snippe, E. , Wichers, M. , Wigman, J. T. W. , Bos, E. H. , Wardenaar, K. J. , and Jonge, P. D. (2016) HowNutsAreTheDutch (HoeGekIsNL): A crowdsourcing study of mental symptoms and strengths. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res., 25: 123–144. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1495.

References

- Abdel‐Khalek A. (2006) Measuring happiness with a single‐item scale. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 34(2), 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell W.A., Ettema J.H.M. (1986) SCL‐90. Handleiding bij een multidimensionale psyhopathologie indicator, Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Baer R., Smith G., Hopkins J., Krietemeyer J., Toney L. (2006) Using self‐report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. DOI: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R.A., Smith G.T., Lykins E., Button D., Krietemeyer J., Sauer S., Walsh E., Duggan D., Williams J.M.G. (2008) Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342, DOI: 10.1177/1073191107313003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barge‐Schaapveld D.Q.C.M., Nicolson N.A., Berkhof J., deVries M.W. (1999) Quality of life in depression: daily life determinants and variability. Psychiatry Research, 88(3), 173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron‐Cohen S., Wheelwright S. (2004) The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 163–175. DOI: 10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L., Russell J. (1998) Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 967–984. [Google Scholar]

- Bevelander K.E., Kaipainen K., Swain R., Dohle S., Bongard J.C., Hines P.D.H., Wansink B. (2014) Crowdsourcing novel childhood predictors of adult obesity. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e87756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw F., van der Krieke L., Bos E., Emerencia A.C., Jeronimus B.F., Schenk M., de Vos S., Wardenaar K., Wanders R., Wigman H., Aiello M., de Jonge P. (2014) HowNutsAreTheDutch: personalized feedback on a national scale. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) Fall Symposium Series, DOI: 10.13140/2.1.4203.1683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Davis A., Rafaeli E. (2003) Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos E.H., Snippe E., de Jonge P., Jeronimus B.F. (In preparation) Preserving mental wellbeing in the face of psychopathology: buffering effects of personal strengths and resources. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brabham D.C. (2008) Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving: an introduction and cases. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(1), 75–90. DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt P.T., Williams J.T. (2007) Multiple Time Series Models, Thousand Oaks: CA, Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clark L.A., Watson D. (1991) Tripartite model of anxiety and depression – psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L.A., Watson D., Reynolds S. (1995) Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology – challenges to the current system and future‐directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 121–153. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collip I., Oorschot M., Thewissen V., Van Os J., Bentall R., Myin‐Germeys I. (2011) Social world interactions: how company connects to paranoia. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 911–921. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291710001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon D.M., Revelle W. (2014) The international cognitive ability resource: development and initial validation of a public‐domain measure. Intelligence, 43(0), 52–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M., Larson R. (1987) Validity and reliability of the experience‐sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–536. DOI: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. (1859) The Origin of Species, London, Collector's Library: CRW Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf R., ten Have M., van Dorsselaer S. (2010) The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study‐2 (NEMESIS‐2): design and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19(3), 125–141. DOI: 10.1002/mpr.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean K., Stevens H., Mortensen P.B., Murray R.M., Walsh E., Pedersen C.B. (2010) Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(8), 822–829. DOI: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beurs E., van Dyck R., Marquenie L.A., Lange A., Blonk R.W.B. (2001) De DASS; een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress. Gedragstherapie, 34, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F., Hoekstra H. (2014) NEO‐PI‐3 persoonlijkheidsvragenlijst, Amsterdam: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- De Klerk M., Van Yperen N.W., Postma S., Kamsma P.Y.J. (2003) Doen, voelen en denken: drie gedragsstijlen toegepast in de organisatieadviespraktijk. Gedrag En Organisatie, 3, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Dehue T. (2014) Betere mensen, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Augustus. [Google Scholar]

- Doane L.D., Adam E.K. (2010) Loneliness and cortisol: momentary, day‐to‐day, and trait associations. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(3), 430–441. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré B., Ort L., Braverman O., Ochsner K.N. (2015) Sadness shifts to anxiety over time and distance from the national tragedy in Newtown, Connecticut. Psychological Science, 26(4), 363–373. DOI: 10.1177/0956797614562218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A.L., Steen T.A., Seligman M.E.P. (2005) Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 629–651. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont F. (2010) A History of Personality Psychology: Theory, Science, and Research from Hellenism to the Twenty‐first Century, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin C.E., Hicks B.M. (2014) Personality and psychopathology: a stagnant field in need of development. European Journal of Personality, 28(4), 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerencia A.C., van der Krieke L., Bos E., de Jonge P., Petkov N., Aiello M. (2015) Automating vector autoregression on electronic patient diary data. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. DOI: 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2402280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce M.W. (1988) A review of research on the happiness measures: a sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research, 20(4), 355–381. [Google Scholar]

- George J.M., Jones G.R. (2002) Organizational Behavior, 3rd edn, NJ, Pearson: Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Glaesmer H., Rief W., Martin A., Mewes R., Brähler E., Zenger M., Hinz A. (2012) Psychometric properties and population‐based norms of the life orientation test revised (LOT‐R). British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(2), 432–445. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S., Vazire S., Srivastava S., John O. (2004) Should we trust web‐based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59(2), 93–104. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez F., Navinés R., Navarro P., García‐Esteve L., Subirá S., Torrens M., Martín‐Santos R. (2008) What do all personality disorders have in common? Ineffectiveness and uncooperativeness. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(6), 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand E. (2010) People power. Nature, 466(7307), 685–687. DOI: 10.1038/466685a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness K.L., Luther J. (2001) Clinical risk factors for the generation of life events in major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S.P., Stier A. (2008) Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 367–393. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A.V., Wakefield J.C. (2007) The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder, New York: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe J. (2006) Crowdsourcing: A definition, http://www.crowdsourcing.typepad.com/cs/2006/06/crowdsourcing_a.html [2 June 2006].

- Huber M., Knottnerus J.A., Green L., Horst H.v.d., Jadad A.R., Kromhout D., Leonard B., Lorig K., Loureiro M.I., van der Meer J.W.M., Schnabel P., Smith R., van Weel C., Smid H. (2011) How should we define health?, BMJ, 343, d4163 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman S.E. (2007) Can neuroscience be integrated into the DSM‐V? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 8(9), 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T. (2013) Transforming diagnosis, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml [29 April 2013].

- Jeronimus B.F., van der Krieke L., Blaauw F.J., Schenk H.M., Slaets J., Emerencia A.C., de Jonge P. (Submitted for publication) In search of wisdom among the elderly: a study of subjective wellbeing across the lifespan (Study 1) and the role of capabilities (Study 2) in the Netherlands.

- Jeronimus B.F., Ormel J., Aleman A., Penninx B.W.J.H., Riese H. (2013) Negative and positive life events predict small but long‐term change in neuroticism. Psychological Medicine, 43(11), 2403–2415. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291713000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S., Phillips A.G., Insel T.R. (2012) Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Molecular Psychiatry, 17(12), 1174–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell R., Jablensky A. (2003) Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 4–12. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S. (1996) Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder – same genes, (partly) different environments – revisited. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S. (2008) Explanatory models for psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(6), 695–702. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S. (2012) The dappled nature of causes of psychiatric illness: replacing the organic‐functional/hardware‐software dichotomy with empirically based pluralism. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(4), 377–388. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2011.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S., First M.B. (2010) Alternative futures for the DSM revision process: iteration v. paradigm shift. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(4), 263–265. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S., Parnas J. (eds). (2015) Philosophical Issues in Psychiatry III: The Nature and Sources of Historical Change, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S., Zachar P., Craver C. (2011) What kinds of things are psychiatric disorders? Psychological Medicine, 41(6), 1143–1150. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291710001844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K.R., Walters E.E. (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM‐IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C.L.M. (2007) Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra T.A., Sijtsema J.J., Henrichs J., Cima M. (2014) The dark triad of personality in adolescence: psychometric properties of a concise measure and associations with adolescent adjustment from a multi‐informant perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 53(0), 84–92. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konings M., Bak M., Hanssen M., Van Os J., Krabbendam L. (2006) Validity and reliability of the CAPE: a self‐report instrument for the measurement of psychotic experiences in the general population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(1), 55–61. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. (2002) The PHQ‐15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(2), 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R.F. (1999) The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(10), 921–926. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R.F., Markon K.E. (2006) Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model‐based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 111 DOI: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer D.J.F., First M.B., Regier D.A. (2002) A Research Agenda for DSM‐V, Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Lamiell J.T. (1998) `Nomothetic” and `Idiographic”: contrasting windelband's understanding with contemporary usage. Theory & Psychology, 8(1), 23–38. DOI: 10.1177/0959354398081002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet T. (2009) What is health? The ability to adapt. The Lancet, 373(9666), 781 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J.S. (1999) The conceptualization of health. Medical Care Research and Review, 56(2), 123–136. DOI: 10.1177/107755879905600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]