Abstract

Subjective assessment may be incomparable across countries due to differences in reporting styles. Based on two nationally representative surveys from the US and China, this study used data from three anchoring vignettes to estimate to what extent the US and Chinese older adults aged 50 and above differed in their reporting styles of subjective cognitive impairment. Cross country differences of subjective cognitive impairment were then estimated, both before and after adjusting for reporting heterogeneity. Directly assessed word recall test scores were analyzed to evaluate whether findings based on subjective cognitive impairment was consistent with objective performance. The results revealed a discrepancy between self‐reported subjective cognitive impairment and directly assessed memory function among older adults: while Chinese respondents reported lower severity levels of subjective cognitive impairment, the US respondents demonstrated better performance in immediate word recall tests. By accounting for differences in reporting styles using anchoring vignettes data, Chinese older adults showed higher levels of subjective cognitive impairment than the US older adults, which was consistent with results from direct assessment of memory function. Non‐negligible differences are present in reporting styles of subjective cognitive impairment. Cross country comparison needs to take into account such reporting heterogeneity. Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: subjective cognitive impairment, response heterogeneity, anchoring vignettes, Health and Retirement Study, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

Introduction

It has been well established that differences in reporting styles may invalidate direct comparisons of subjective ratings across different cultural groups (Hopkins and King, 2010). While previous research has provided evidence that a direct comparison could be very misleading in areas like political efficacy and self‐rated disability (Kapteyn et al., 2007; King et al., 2004), not much is known about self‐rated cognition.

In recent years, researchers have been arguing for the possibility of using subjective cognitive impairment or memory complaints as part of a diagnostic tool of early identification of cognitive disorder (Jessen et al., 2010; Waldorff et al., 2012; Mitchell, 2008). According to a recent meta‐analysis, the consistency between subjective memory and objective memory varies across studies with a positive but small average correlation of 0.062 (Crumley et al., 2014). An overall average weak association may be attributed to a number of causes. For example, some people may be less aware of their cognitive status than others (Zelinski et al., 2001). Social desirability may be another reason that would produce some mismatch between the objective and subjective measures, especially among the aging population (Fastame and Penna, 2012). Previous studies have shown that Asians are likely to view problems with mental state as a social stigma and tend to delay their clinical visit (Chow et al., 2002).

Furthermore, self‐rated cognitive function may be also affected by respondents' reporting styles. Such styles are often very distinct across different cultural groups (Song et al., 2011), and thus have direct implications for the validity of cross‐culture comparisons (Heine et al., 2002). Based on a previous study comparing response styles of college students from 26 countries, Chinese tended to have low disacquiescence, low frequencies in extreme categories and high frequencies in middle categories, while respondents from Western countries showed greater preference for extreme responses, especially towards the positive end of the response scale (Harzing, 2006; Mõttus et al., 2012).

Variations in reporting styles may be explained by the reference group hypothesis, which posits that people's perceptions of their status are largely formed by the circle of people whom they interact with (Evans and Kelley, 2004). In other words, people develop perceptions of their subjective location based on their own experiences and those of similar others (Franzini and Fernandez‐Esquer, 2006). Previous studies comparing the memory performance of older adults from China and the United States have reported large gaps between the two populations in favor of the US population (Skirbekk et al., 2012). If the reference group hypothesis holds, Chinese older adults may use lower standards in evaluating the cognitive status of the elderly.

In addition to the reference group hypothesis, cultural differences may also contribute to variations in reporting styles of self‐rated cognition. The Chinese culture places great emphasis on respect for the elders and parents, and they tend to regard the slow progression in memory impairment as part of the normal aging process, and thus may have higher levels of acceptance of memory loss with aging (Löckenhoff et al., 2009; Chow et al., 2002).

Anchoring vignettes are a possible design to address reporting heterogeneity (King et al., 2004). Anchoring vignettes are descriptions of hypothetical cases characterized by the most salient objective features of a person or a situation. For example, the following is an anchoring vignette item used in a sub‐study of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS).

Vignette 1 —

“Lisa can concentrate while watching TV, reading a magazine or playing a game of cards or chess. Once a week she forgets where her keys or glasses are, but finds them within five minutes. Overall, in the last 30 days, how much difficulty did Lisa have with concentrating or remembering things?”

The following options are given: 1 (None), Mild (2), Moderate (3), Severe (4), and Extreme (5). Responses to anchoring vignettes can help identify heterogeneity in respondents' reporting styles, and such heterogeneity can then be taken into account when analyzing self‐reported data (Dowd and Todd, 2011). Vignette equivalence and response consistency are two important basic assumptions of the anchoring vignettes (King et al., 2004). Vignette equivalence means that all individuals perceive the anchoring items in the same way; therefore any variation in the responses to the anchoring items reflects differences in response styles. Response consistency means that the same reporting standards are applied for both the anchoring vignettes and the self‐assessment question.

Purpose

The current study explores how a number of key demographic factors including age, gender, and education may affect reporting behaviors when evaluating subjective cognitive impairment, with a particular interest in how respondents from China and the United States would respond to the same three anchoring vignettes in different ways. Furthermore, the study evaluated whether adjusting for reporting heterogeneity based on anchoring vignettes would bring the results from subjective ratings closer to findings based on directly assessed memories. Although directly assessed memories are not perfect measures of objective cognitive function, they provide an invaluable opportunity to validate anchoring vignettes, as an objective counterpart is usually non‐existent in studies using anchoring vignettes (Datta Gupta et al., 2010).

Method

Data sources

Data are from HRS in the United States, and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal study of US adults aged 50+ and their spouses (Juster and Suzman, 1995). Over the years, several enrollment cohorts entered the study in 1992, 1993, 1998, 2004, and 2010, respectively. Respondents completed approximately biennial interviews about health, including brief cognitive assessments. In 2007, HRS administered the Disability Vignette Survey (DVS) as its sub‐study (Dowd and Todd, 2011), which included self‐rated and anchoring vignettes questions on various aspects of health status. CHARLS is a nationally representative study of Chinese adults aged 45+ (Zhao et al., 2013). Its study design was based on HRS and other related aging surveys such as the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA) and the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). CHARLS baseline survey collected data on over 17,500 individuals from 450 communities in China.

Sample

The current analysis focused on respondents aged 50+ from a sub‐sample who took the self‐rated memory impairment question. A smaller sub‐sample of those respondents also completed the anchoring vignettes items. Note that the DVS administered two forms of anchoring vignettes questions characterized by different orders of anchoring vignettes, and the current study only retained anchoring vignettes responses from those who took forms with the same order as CHARLS, which led to an analytical sample of 4408 HRS respondents who answered the self‐rated question, and a sub‐sample of 2211 HRS respondents who answered the anchoring vignettes. Number of CHARLS respondents who answered the self‐rated and anchoring vignettes questions on subjective cognitive impairment were 2862 and 872, respectively. The Chinese and the US sample were vastly different in terms of educational attainment: while a majority of the US respondents had at least high school education, over half of the Chinese sample did not even complete primary education (see Table 1). In addition, the Chinese sample was about four years younger and included more males.

Table 1.

Key demographic characteristics of the United States (US) and Chinese sample of older adults

| Characteristics | US (N = 4,419) | China (N = 2,869) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 66.3 (SD = 10.1) | 62.2 (SD = 8.5) |

| Male | 40.2% | 47.8% |

| Education | ||

| Less than primary | 2.1% | 50.6% |

| Primary | 4.5% | 22.7% |

| Junior High | 9.4% | 15.2% |

| High school+ | 84.0% | 11.5% |

Note: SD, standard deviation.

Measures

Self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment was measured by a single item (“Overall, in the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have with concentrating or remembering things?”). Response options for self‐ratings were the same as those for the anchoring vignettes, ranging from none (1) to extreme (5), with higher scores indicating higher levels of impairment. The Chinese and US samples were administered largely the same vignette questions, differed mainly by the names of the hypothetical persons. While the HRS used common US names in the vignettes, the CHARLS used common Chinese names. DVS Vignette 1 has already been mentioned in the introduction section. The other two anchoring vignettes are shown here.

Vignette 2 —

Sue is keen to learn new recipes but finds that she often makes mistakes and has to reread several times before she is able to do them properly.

Vignette 3 —

Eve cannot concentrate for more than 15 minutes and has difficulty paying attention to what is being said to her. Whenever she starts a task, she never manages to finish it and often forgets what she was doing. She is able to learn the names of people she meets.

Objective memory function was measured by the immediate word recall test. Immediate word recall test was considered a brief test of short‐term memory and has been used in previous studies of international comparisons (Skirbekk et al., 2012). The interviewer reads one of four possible lists of 10 nouns to the respondent, and asks the respondent to recall as many words as possible from the list in any order. Scores were computed by counting the number of words that were recalled correctly. Both CHARLS and HRS word lists included the most common nouns frequently used on a daily basis.

Analysis

King et al. (2004) proposed a parametric model to deal with reporting heterogeneity, where thresholds were estimated incorporating information from the anchoring vignettes, and the model is called the compound hierarchical ordered probit (CHOPIT) model (Rabe‐Hesketh and Skrondal, 2002). There are two main components of the CHOPIT model, the self‐assessment part and the anchoring vignettes part. The self‐assessment part specifies that for every individual i, there is an unobserved perceived continuous outcome underlying the observed and reported categorical outcome Y i with K possible levels. Values of are a function of the observed covariate set Xi, as in Equation 1, and are converted to Y i based on Equation 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

The self‐assessment part is analogous to an ordered probit model except that in Equation 2, threshold values are allowed to vary across individuals as a function of a set of covariates Vi, which may overlap with Xi.

| (3) |

The vignette part specifies that individuals perceive anchoring item l only with a random error term σ.

| (4) |

| (5) |

Based on the vignette equivalence assumption, θ l is the same for all individuals. Additionally, the same set of τ values are used across the self‐assessment and the anchoring vignettes for the same individual under the response consistency assumption. Because the self‐assessment and the anchoring vignette models share the same parameters regarding thresholds, their likelihood functions are estimated simultaneously. For more details on the parameter estimations, readers may consult King et al. (2004). The CHOPIT model has been used to adjust for response style differences in cross country comparisons of drinking behavior (van Soest et al., 2011) and self‐rated health (Bago d'Uva et al., 2008), among other things.

The current analysis consists of the following steps. First, the study examined how Chinese and US older adults rated the three anchoring vignettes and whether such ratings were associated with age, gender and education levels. Second, self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment scores and directly assessed memory scores were both compared between Chinese and US older adults, without adjusting for response heterogeneity. The last step involved using the CHOPIT model to adjust for differences in reporting styles. Analysis was done mainly with the anchors package (Wand et al., 2011) and the polr procedure in R.

Results

Anchoring vignettes

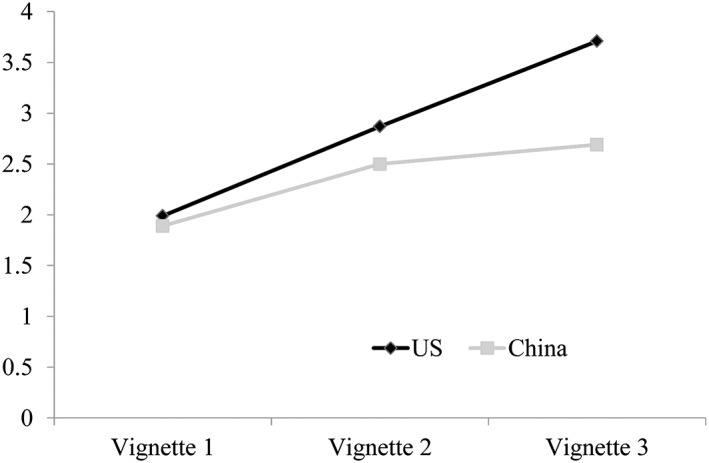

Average severity ratings of the three anchoring vignettes by the US and Chinese respondents are presented in Figure 1. Both the US and Chinese older adults agreed on the relative severities of the three hypothetical cases in general, as demonstrated by the increasing levels of average rated severities of the three anchoring vignettes. However, the absolute levels of the ratings were different across the two countries, with the Chinese endorsing overall lower levels of severity ratings across all three anchoring vignettes. The difference was more salient for the more severe anchoring vignettes: while there was only minor difference for Vignette 1 between the two populations, Chinese on average assigned much lower levels of severity ratings to Vignette 3 than the US older adults.

Figure 1.

Average severity ratings on three anchoring vignettes based on US and Chinese older adults (higher ratings indicate more severe).

Ordered probit regressions revealed a significant country effect for all three anchoring vignettes after controlling for differences in age, gender and education categories, with Chinese showing greater preference for lower severity ratings (see Table 2), which was consistent with results from Figure 1. Interestingly, age, gender and education showed significant effects only for Vignette 1, where older, male, and lower educated respondents tended to endorse higher severity ratings. Note that the estimates were from probit regression in R, where the direction of the coefficients corresponded to the original scale, i.e. negative coefficients indicated lower ratings.

Table 2.

Results from ordered probit models on ratings of anchoring vignettes

| Vignette 1 | Vignette 2 | Vignette 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | T | Value | T | Value | T | |

| China (versus US) | −0.45*** | −6.84 | −0.54*** | −8.31 | −1.07*** | −16.30 |

| Male | 0.17*** | 4.21 | 0.06 | 1.65 | −0.07 | −1.87 |

| Age | ||||||

| Reference: 50–59 years | ||||||

| 60+ | 0.06 | 1.32 | −0.06 | −1.17 | 0.02 | 0.39 |

| 70+ | 0.14* | 2.49 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.62 |

| 80+ | 0.24*** | 3.32 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −1.85 |

| Education | ||||||

| Reference: illiterate | ||||||

| Primary | −0.13 | −1.54 | 0.05 | 0.59 | −0.04 | −0.57 |

| Junior High | −0.22** | −2.59 | 0.11 | 1.31 | −0.02 | −0.21 |

| Senior High+ | −0.45*** | −5.78 | −0.05 | −0.73 | 0.12 | 1.65 |

Note. Estimates were from probit regression in R, where the direction of the coefficients corresponded to the original scale, i.e. negative coefficients indicated lower ratings.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment and directly assessed memory scores

The left panel of Table 3 shows the results from ordinary least squares regression using word immediate recall test scores as the outcome. After controlling for gender, age, and education levels, the Chinese older adults had lower levels of word immediate recall test scores than the US older adults (β = −1.28, p < 0.001). However, this was in contrast to what was found based on ordered probit regression analysis of the self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment (see Table 3 middle panel), where the Chinese demonstrated lower severity levels of self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment (β = −0.39, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Results from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression on word immediate recall, ordered probit (OP) regression on subjective cognitive impairment and CHOPIT model on subjective cognitive impairment

| Word immediate recall | Subjective cognitive impairment | Subjective cognitive impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (OLS) | (OP) | (CHOPIT) | ||||

| Value | T | Value | T | Value | T | |

| China (versus US) | −1.28*** | −20.99 | −0.39*** | −9.02 | 0.18** | 3.387 |

| Male (versus female) | −0.31*** | −7.8 | −0.08** | −2.93 | −0.10** | −3.04 |

| Age group | ||||||

| Reference: 50–59 years | ||||||

| 60+ | −0.19*** | −4.12 | 0.10** | 3.13 | 0.08** | 2.11 |

| 70+ | −0.73*** | −13.41 | 0.18*** | 4.81 | 0.11** | 2.51 |

| 80+ | −1.48*** | −20.56 | 0.49*** | 10.1 | 0.43*** | 7.32 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Reference: illiterate | ||||||

| Primary | 0.77*** | 10.86 | −0.29*** | −5.96 | −0.28*** | −4.68 |

| Junior High | 1.20*** | 15.97 | −0.38*** | −7.37 | −0.35*** | −5.54 |

| Senior High+ | 1.86*** | 25.91 | −0.70*** | −13.82 | −0.63*** | −10.39 |

Note: for interpretation of estimates, see footnote of Table 2.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

In addition to the country effect, the effects of gender were also inconsistent across the objective and subjective measures: while males had lower average scores with the immediate word recall test (β = −0.31, p < 0.001), they perceived a less severe level of self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment (β = −0.08, p < 0.01). The general effects of age group and education level were consistent across the directly assessed recall test scores and the self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment, as both models demonstrated lower cognitive function with older age and lower education levels.

Adjusting for reporting heterogeneity using anchoring vignettes

The last set of analysis used the CHOPIT model to address reporting style differences across different groups, and the results are presented in the right panel of Table 3. Note that CHOPIT model was also estimated in R, and the coefficients can be interpreted in the same way as those in Table 2, that is, negative effects indicate lower average ratings on severity of subjective cognitive impairment.

The most significant change from the ordered probit model to the CHOPIT model was related to the country effect: while the ordered probit unadjusted for reporting heterogeneity showed that the Chinese respondents had lower severity levels of subjective cognitive impairment than the US respondents (β = −0.39, p < 0.001), the CHOPIT model indicated the opposite (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), which became consistent with the findings based on direct word recall test scores. The directions of the effects from other covariates remained unchanged from the ordered probit model, but the magnitudes of age groups and education levels were somewhat attenuated.

As a further step to validate the adjustment, parameter estimates of the ordered probit model and the CHOPIT model from Table 3 were plugged into Equation 1 to compute a predicted value for all individuals. Similar validation was done in van Soest et al. (2011). Such predicted values present the systematic part of the estimated perceived levels of self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment before (ordered probit‐based values) and after (CHOPIT‐based values) adjustment for reporting style differences. The CHOPIT‐based values had a much stronger correlation with the immediate word recall test scores (r = −0.55, p < 0.001) than the ordered probit‐based values (r = −0.29, p < 0.001), which suggested that the adjustment improved the consistency between objective and subjective measures.

Discussion

Cross‐country differences in reporting styles have been shown to be a great cause of concern when comparing subjective ratings from different countries (King et al., 2004). If such reporting heterogeneity is not considered, direct comparisons may produce misleading conclusions when subjective ratings are interpreted as some reflections of the objective reality (Salomon et al., 2004). This study utilized both anchoring vignettes and self‐ratings from the HRS in the United States and CHARLS in China, and found that when reporting style differences were not taken into account, cross‐country comparisons of self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment contradicted directly assessed memory functions based on the immediate word recall tests. However, when the model was enhanced with information from anchoring vignettes to adjust for response heterogeneity, cross‐country comparisons based on subjective cognitive impairment were consistent with directly assessed memory function.

Consistent with prior literature, the current study reported notable differences in absolute levels of ratings of the same three anchoring vignettes across different groups of respondents (Dowd and Todd, 2011). For all the three anchoring vignettes with different levels of severities, the Chinese respondents consistently gave lower levels of severities than the US respondents did, and cross‐country differences were larger for vignettes with higher levels of subjective cognitive impairment. Further analyses with a number of key demographic variables indicated that compared with age, gender, and education levels, country effects on reporting styles were the most consistent and also the strongest across the three anchoring vignettes. This confirms the importance of taking response heterogeneity into account when doing cross‐culture comparisons (Mõttus et al., 2012).

However, the current results were not consistent with previous findings of a strong tendency of the Chinese to endorse the middle categories (Harzing, 2006). Chinese older adults appeared to favor the lower end of the severity scale more so than the US counterparts, both based on anchoring vignettes ratings and self‐ratings in the current study. Such discrepancy may be due to differences in types of response options. The Harzing study focused on response options that were highly symmetrical, for example, from strongly disagree to strongly agree, which was different from option settings from none to the extreme in this study.

The observed country difference in reporting styles of anchoring vignettes on subjective cognitive impairment is consistent with the reference group theory (Heine et al., 2002), because groups with lower levels of cognitive function (i.e. the Chinese) according to previous research (Skirbekk et al., 2012) indeed showed lower standards in evaluating the cognitive function and thus assigned lower severity ratings to the same anchoring vignettes. However, effects of age and education levels on ratings of anchoring vignettes were not consistent with the reference group theory.

This study adds to the current literature in the following aspects. First, this is the first study to conduct cross‐country comparisons of subjective cognitive impairment while taking reporting heterogeneity into account, although previous studies have done so across different cultural groups within the same country (Dowd and Todd, 2011). Second, the use of the directly assessed word recall test scores provides empirical support to verify that adjusting for reporting heterogeneity based on anchoring vignettes brings findings based on subjective ratings closer to the objective measures.

An important caveat must be raised that the use of anchoring vignettes could help partial out differences in response styles that are applied to both the self‐assessment and the ratings of anchoring vignettes (i.e. response consistency). In other words, anchoring vignettes would not be able to deal with social desirability because it is likely to be only applicable to the self‐assessment but not anchoring vignettes. For example, although the CHOPIT‐based model managed to bring in consistency between subjective and objective measures in US versus China comparisons, it did not resolve the discrepancy between the two measures across different gender groups (i.e. males had worse word recall test scores but rated themselves as having less difficulty). One possibility is that males have a stronger tendency to give socially desirable answer to the self‐assessment question than females. Since this tendency was unlikely to be reflected in ratings of anchoring vignettes, the CHOPIT model would not be able to resolve it.

The study also has several limitations: first, although immediate word recall test scores provide important information as a measure of objective memory function, it only reflects part of cognitive function, and is by no means a perfect measure to verify the validity of the self‐rated subjective cognitive impairment which explicitly asked the respondent about their difficulty with both concentration and memory. Second, the CHOPIT model only considered a few key demographic covariates because those variables were unlikely to have comparability problems across countries, but ignoring other potentially important covariates (e.g. depression) may mask interesting findings. However, the use of a covariate which itself may be influenced by reporting styles (e.g. depression) to adjust for differences in reporting styles of another variable warrants the investigation of another study. Third, although ratings on anchoring vignettes presented evidence for the existence of notable response style differences between the Chinese and the US older adults, the current study were unable to attribute such differences to either social comparisons or cultural differences or other potential causes.

Conclusion

Despite worse cognitive performance based on directly assessed word recall test scores, the Chinese older adults aged 50+ reported lower severity levels of subjective cognitive impairment than the US adults. Such discrepancy was likely due to reporting style heterogeneity across the two populations, which was reflected in notable differences of their average ratings on three anchoring vignettes. After adjusting for reporting heterogeneity using data from the anchoring vignettes, the Chinese older adults showed higher levels of subjective cognitive impairment than the US older adults. Failing to consider cross‐country differences in reporting styles may yield misleading conclusions based on subjective evaluations of cognitive impairment.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests.

Wu, Q. (2016) Subjective cognitive impairment of older adults: a comparison between the US and China. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res., 25: 68–75. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1499.

References

- Bago D'Uva T., O'Donnell O., Van Doorslaer E. (2008) Differential health reporting by education level and its impact on the measurement of health inequalities among older europeans. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37, 1375–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow T.W., Liu C.K., Fuh J.L., Leung V.P.Y., Tai C.T., Chen L.‐W., Wang S.J., Chiu H.F.K., Lam L.C.W., Chen Q.L., Cummings J.L. (2002) Neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer's disease differ in Chinese and American patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumley J.J., Stetler C.A., Horhota M. (2014) Examining the relationship between subjective and objective memory performance in older adults: a meta‐analysis. Psychology and Aging, 29, 250–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta Gupta N., Kristensen N., Pozzoli D. (2010) External validation of the use of vignettes in cross‐country health studies. Economic Modelling, 27, 854–865. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd J.B., Todd M. (2011) Does self‐reported health bias the measurement of health inequalities in U.S. adults? Evidence using anchoring vignettes from the Health and Retirement Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66b, 478–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M.D.R., Kelley J. (2004) Subjective social location: data from 21 nations. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 16, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fastame M.C., Penna M.P. (2012) Does social desirability confound the assessment of self‐reported measures of well‐being and metacognitive efficiency in young and older adults? Clinical Gerontologist, 35, 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L., Fernandez‐Esquer M.E. (2006) The association of subjective social status and health in low‐income Mexican‐origin individuals in Texas. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 788–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzing A.‐W. (2006) Response styles in cross‐national survey research: a 26‐country study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 6, 243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Heine S.J., Lehman D.R., Peng K., Greenholtz J. (2002) What's wrong with cross‐cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference‐group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D.J., King G. (2010) Improving anchoring vignettes: designing surveys to correct interpersonal incomparability. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F., Wiese B., Bachmann C., Eifflaender‐Gorfer S., Haller F., K Lsch H., Luck T., M Sch E., van den Bussche H., Wagner M., Wollny A., Zimmermann T., Pentzek M., Riedel‐Heller S., Romberg H., Weyerer S., Kaduszkiewicz H., Maier W., Bickel H. (2010) Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster F., Suzman R. (1995) An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources, 30(Supplement), S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn A., Smith J.P., Soest A.V. (2007) Vignettes and self‐reports of work disability in the United States and the Netherlands. The American Economic Review, 97, 461–473. [Google Scholar]

- King G., Murray C.J.L., Salomon J.A., Tandon A. (2004) Enhancing the validity and cross‐cultural comparability of measurement in survey research. American Political Science Review, 98, 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff C.E., De Fruyt F., Terracciano A., Mccrae R.R., De Bolle M., Costa P.T., Jr. , Aguilar‐Vafaie M.E., Ahn C.‐K., Ahn H.‐N., Alcalay L., Allik J., Avdeyeva T.V., Barbaranelli C., Benet‐Martinez V., Blatný M., Bratko D., Cain T.R., Crawford J.T., Lima M.P., Ficková E., Gheorghiu M., Halberstadt J., Hřebičková M., Jussim L., Klinkosz W., Knežević G., De Figueroa N.L., Martin T.A., Marušić I., Mastor K.A., Miramontez D.R., Nakazato K., Nansubuga F., Pramila V.S., Realo A., Rolland J.‐P., Rossier J., Schmidt V., Sekowski A., Shakespeare‐Finch J., Shimonaka Y., Simonetti F., Siuta J., Smith P.B., Szmigielska B., Wang L., Yamaguchi M., Yik M. (2009) Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture‐level associates. Psychology and Aging, 24, 941–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mõttus R., Allik J., Realo A., Rossier J., Zecca G., Ah‐Kion J., Amoussou‐Yéyé D., Bäckström M., Barkauskiene R., Barry O., Bhowon U., Björklund F., Bochaver A., Bochaver K., De Bruin G., Cabrera H.F., Chen S.X., Church A.T., Cissé D.D., Dahourou D., Feng X., Guan Y., Hwang H.‐S., Idris F., Katigbak M.S., Kuppens P., Kwiatkowska A., Laurinavicius A., Mastor K.A., Matsumoto D., Riemann R., Schug J., Simpson B., Tseung‐Wong C.N., Johnson W. (2012) The effect of response style on self‐reported conscientiousness across 20 countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1423–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A.J. (2008) The clinical significance of subjective memory complaints in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta‐analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 1191–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe‐Hesketh N., Skrondal A. (2002) Estimating CHOPIT Models in Gllamm – Political Efficacy Example from King et al . http://www.gllamm.org/chopit.pdf [9 January 2015].

- Salomon J.A., Tandon A., Murray C.J.L. (2004) Comparability of self rated health: cross sectional multi‐country survey using anchoring vignettes. British Medical Journal, 328, 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirbekk V., Loichinger E., Weber D. (2012) Variation in cognitive functioning as a refined approach to comparing aging across countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Cai H., Brown J.D., Grimm K.J. (2011) Differential item functioning of the Rosenberg self‐esteem scale in the US and China: measurement bias matters. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 14, 176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest A., Delaney L., Harmon C., Kapteyn A., Smith J.P. (2011) Validating the use of anchoring vignettes for the correction of response scale differences in subjective questions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 174, 575–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldorff F.B., Siersma V., Vogel A., Waldemar G. (2012) Subjective memory complaints in general practice predicts future dementia: a 4‐year follow‐up study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand J., King G., Lau O. (2011) Anchors: software for anchoing vignette data. Journal of Statistical Software, 42, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski E.M., Burnight K.P., Lane C.J. (2001). The relationship between subjective and objective memory in the oldest old: Comparisons of findings from a representative and a convenience sample. Journal of Aging and Health, 13, 248–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Strauss J., Yang G., Giles J., Hu P., Hu Y., Lei X., Park A., Smith J.P., Wang Y. (2013) China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study: 2011–2012 National Baseline Users' Guide, Beijing: Peking University. [Google Scholar]