Abstract

An accurate diagnosis is essential for the management of late‐life depression in primary care. This study aims to (1) provide information on the agreement on depression diagnoses between general practitioners (GPs), dimensional tools (Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]) and a categorical tool (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV criteria [SCID]) and (2) identify factors associated with different diagnoses. As part of the multicenter study “Late‐life depression in primary care: needs, health care utilization and costs (AgeMooDe)” a sample of 1113 primary care patients aged 75 years and older was assessed. The proportion of depression was 24.3% according to GPs, 21.8% for the GDS, 18.9% for the HADS and 8.2% for the SCID. Taking GDS, HADS and SCID as reference standards, recognition of GPs was 47%, 48% and 63%. Cohen's Kappa values indicate slight to moderate agreement between diagnoses. Multinomial logistic regression models showed that patient related factors of depression were anxiety, intake of antidepressants, female gender, a low state of health, intake of medication for chronic diseases and functional impairment. GPs performed better at ruling out depression than ruling in depression. High levels of disagreement between different perspectives on depression indicate that they may be sensitive to different aspects of depression.

Keywords: depression diagnosis primary care, old age, risk factors

1. INTRODUCTION

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health disorders in late life (Gühne, Stein, & Riedel‐Heller, 2016), but it continues to remain an underdetected (Mitchell, Rao, & Vaze, 2010) and undertreated (Gühne, Luppa et al., 2016; Luppa, Sikorski, Motzek et al., 2012) disease. In fact, depressive disorders in elderly patients may lead to serious consequences as they are associated with impaired cognitive functioning (Korten et al., 2014), reduced health‐related quality of life (Schowalter et al., 2013), increased mortality (Köhler et al., 2013) and suicide rates (Sinyor, Tan, Schaffer, Gallagher, & Shulman, 2016).

A crucial first step in providing care for depressed patients is an early detection using appropriate diagnostic tools (Kivelitz, Watzke, Schulz, Härter, & Melchior, 2015). General practitioners (GPs) play a key role in this concern, because the majority of care for late‐life depression is provided by primary care (Harman, Veazie, & Lyness, 2006; Holvast et al., 2012). In a representative survey of the German population one in five patients recommended professional help from a GP as the first source of help in case of major depression (Riedel‐Heller, Matschinger, & Angermeyer, 2005). Most notably, older patients in the survey were more likely to advise help from the GP. In Germany, GPs code depressive disorders according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD‐10) criteria (World Health Organization, 2010), as this is the prerequisite for reimbursement of treatment costs. However, current guidelines for the diagnosis of depression point out that recognition of depression may be complicated by the fact that depressed patients rarely report typical symptoms of depression spontaneously, but rather present with somatic symptoms or a feeling of general discomfort (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde [DGPPN], Bundesärztekammer [BÄK], Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung [KBV], Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften [AWMF], & Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin [ÄZQ], 2015). These guidelines provide a list of complaints and risk factors that may indicate depression and recommend that in case of suspected depression, screening tools should be applied to identify patients at risk followed by a thorough structured interview based on ICD‐10 criteria. Different studies revealed a potential benefit of assisted diagnostic approaches over the GP's unassisted depression diagnosis (Mitchell, Bird, Rizzo, & Meader, 2010; Østergaard et al., 2010; Pignone et al., 2002; Williams, Pignone, Ramirez, & Perez Stellato, 2002). In order to support depression diagnostics in primary care different categorical and dimensional tools have been developed. Categorical tools such as structured interviews are generally seen as the gold standard for the diagnosis of depression (Moriarty, Gilbody, McMillan, & Manea, 2015) whereas dimensional screening tools were designed to identify patients at risk of depression. However, dimensional approaches are often translated back into categorical approaches through the use of cutoff points.

A previous meta‐analysis showed modest rates of recognition of depression in primary care, which were lowest in older people, but there was a lack of studies considering the perspectives of GPs, dimensional and categorical tools in the same sample. In addition, included studies did not consider factors associated with depression diagnoses according to different perspectives to a sufficient extent (Mitchell et al., 2010).

1.1. Aims of the study

In extension of prior research, this is the first study that assesses the agreement of depression diagnoses in a large sample of oldest old primary care patients considering the perspective of GPs as well as categorical and dimensional perspectives. Therefore, this study aims to (1) provide information on the agreement between the GP's diagnosis and three different measures of depression including recognition rates of GPs and (2) identify factors that are associated with the different diagnoses.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Sample

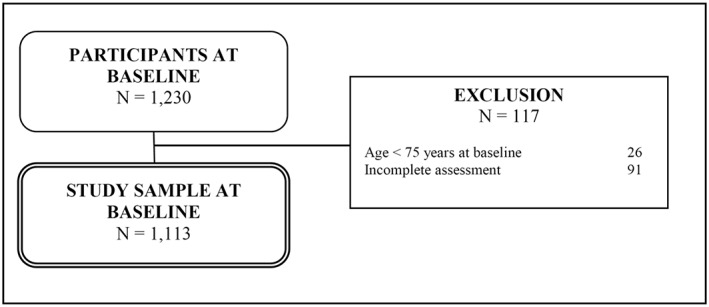

Data were derived from the German AgeMooDe‐study (“Late‐life depression in primary care: needs, health care utilization and costs”). Within this multicenter prospective cohort study patients were recruited from primary care practices in four German cities (Leipzig, Bonn, Hamburg and Mannheim). The baseline assessment was conducted between May 2012 and December 2013, followed by a follow‐up assessment one year later. This study analyzes cross‐sectional data from the baseline‐interview. For participation, patients had to meet the following criteria for inclusion: (1) an age of at least 75 years and (2) a minimum of one contact with the GP within the last six months. Patients were excluded from the study if they had (1) a severe illness which the GP deemed would be fatal within three months, (2) moderate or severe dementia according to ICD‐10 criteria, (3) an insufficient ability to speak and read German language or an inability to provide informed consent. Participating GPs were asked to provide a list of all patients meeting the inclusion criteria and no criteria for exclusion. In the next step, the practice staff was asked to indicate patients with ICD‐10 diagnoses of depression according to the GP on this list as well as the same number of patients with no diagnosis of depression that were randomly selected from this list. Patients who were selected this way were contacted by the GPs and invited to take part in the study via postal mail. This recruitment strategy was easy to implement in small primary care practices and was used in order to investigate a large sample of elderly primary care patients being enriched with depressed individuals (Stein et al., 2016). We finally achieved to examine a total of 110 GPs and 1230 primary care patients at baseline. Of the total sample, 117 patients were excluded from the study sample due to unmet inclusion criteria or missing values in the primary outcome variables addressed in this study. Consequently, the analytical sample of this study consisted of 1113 individuals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of sample selection

2.2. Ethics statement

The study has received ethics committee approval of all participating centers (Ethics approval Leipzig: 020–12‐23012012). All GPs and patients provided written informed consent for participating in the study. All investigations contributing to this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (national and institutional) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

2.3. Procedures and instruments

This study includes a patient assessment and a GP assessment.

2.3.1. Patient assessment

All patients were assessed by trained physicians and psychologists using standardized clinical face‐to‐face interviews at the participants' homes or at university premises. Each interview included a structured set of scales and variables. Socio‐demographic data included the patients' age, gender, marital status (married/with spouse, married/living apart, single, divorced, widowed) and education. Educational level was divided into three levels (low/middle/high) according to the revised version of the new CASMIN educational classification system (Brauns & Steinmann, 1999).

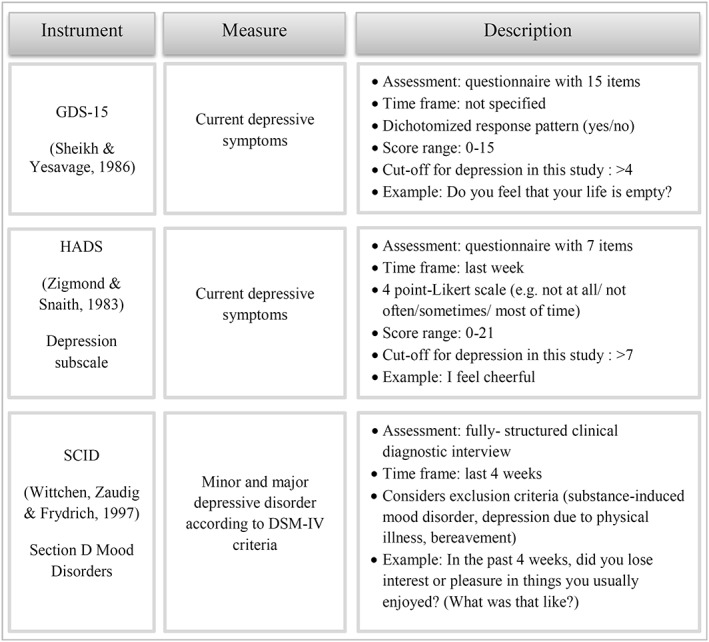

Furthermore, the patient assessment included three different measures for the assessment of depression (see Figure 2): the German short‐form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15; Gauggel & Birkner, 1999; Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986), the German language version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Herrmann, Buss, & Snaith, 1995; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV criteria (SCID; Wittchen, Zaudig, & Fydrich, 1997).

Figure 2.

Overview of the three depression instruments from the patient assessment

2.3.2. Geriatric depression scale (GDS)

The GDS is a 15‐item screening instrument requiring a “yes” or “no” response to each question. The scale was specifically designed for the elderly and has generally demonstrated reliability and validity for major depression as defined by ICD‐10 and DSM‐IV criteria (Almeida & Almeida, 1999). Scores of the single items are summed up to a total score ranging from 0 to 15 with higher scores indicating more severe depression. We used a cutoff >4 to define depression as recommended by Sheikh and Yesavage (1986). In a recent meta‐analysis this cutoff was the most frequently applied score and reached a pooled sensitivity of 0.89 and specificity of 0.77 (Pocklington, Gilbody, Manea, & McMillan, 2016). Since physical complaints become more common with increasing age, the GDS avoids the assessment of somatic symptoms of depression and rather focusses on emotional aspects.

2.3.3. Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

The HADS consists of a depression and an anxiety scale, each containing seven items. The HADS was originally created for the purpose of assessing depression in hospital populations and is supposed to eliminate physically confounded symptoms. All items are rated on a four‐point Likert scale (range 0–3). Hence, the minimum score for depression or anxiety is 0 and the maximum score is 21 with higher scores designating stronger depression and anxiety, respectively. Zigmond and Snaith (1983) recommend a cutoff score >7 for possible cases and >10 for probable cases of depression. In this study we used a cutoff >7 to include also those patients with mild depressive symptoms.

2.3.4. Structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV (SCID)

As a categorical measure for depression the module for mood disorders from the SCID was conducted in this study. A SCID diagnosis included both patients with minor and major depression according to DSM‐IV criteria.

2.3.5. Other instruments

Different illness‐related factors were assessed in the patient interview. Given that depression is associated with cognitive disturbance (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2010), the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) was conducted to screen for cognitive impairment. The MMSE covers orientation, memory, attention, language and visual construction. The maximum total score is 30. Tombaugh and McIntyre (1992) recommend a cutoff score of ≤23 for mild cognitive impairment and ≤17 for severe cognitive impairment. Moreover, (instrumental) activities of daily living (ADL and IADL) were examined with an instrument consisting of 24 items, as proposed by Schneekloth and Potthoff (1993). This instrument assesses independent living skills such as the ability to perform one's own body care, mobility, food preparation, responsibility for own medications, housekeeping, using public transport, ability to use the telephone, visiting people, ability to orientate oneself outside and the ability to handle finances. Patients who had difficulties in at least one skill of the ADL/IADL were categorized as functionally impaired (cutoff ≤23). In addition, the German version of the chronic disease score (CDS) was calculated for each patient by adding up the number of drugs taken for chronic medical conditions or progressive illnesses. The CDS excludes psychotropic medication and medication taken primarily for symptom management such as analgesics. The patients' current state of health was measured with the help of a visual analogue scale from the EQ‐5D (VAS EQ‐5D) of the EuroQol Group (Brooks, 1996) ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating a better state of subjective health. Further, patients were asked whether they currently took antidepressants or not. In accordance with Maske et al. (2016), who examined correlates of different depression diagnoses, social support was assessed. This was realized with a German adaptation of the Enriched Social Support Inventory (ESSI‐D; Kendel et al., 2011). The scale consists of five items which are rated on a five‐point Likert‐scale, leading to a total score range from 5 to 25. Based on the original version of the ESSI (ENRICHD‐Investigators, 2000) the cutoff for poor social support is defined as a total score of ≤18.

2.3.6. General practitioner's (GP's) assessment

All GPs received a short questionnaire where they stated their age, gender and professional experience (length of work experience in years, psychiatric/psychotherapeutic training and experience in treatment of mental illnesses). In addition, the GPs were asked to fill in a questionnaire for each of their recruited patients. In this patient‐based questionnaire the GPs specified in a list of 35 chronic diseases according to the ICD‐10 classification system whether or not the patient suffered from an unremitted depression (ICD‐code F32–F33; World Health Organization, 2010).

2.4. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Stata 13.1 SE (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive values are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) or absolute frequencies and percentages. Due to missing values ranging from 0.1 (marital status) to 5.4% (MMSE), not all socio‐demographic data are based on the total sample. Agreement between all four depression diagnoses was calculated pairwise using Cohen's Kappa (Cohen, 1960). As our analytical sample excludes patients with missing data on primary outcome variables, Kappa values are based on complete cases. In order to calculate corresponding confidence intervals bias‐corrected bootstrap estimates with 500 replications were conducted using kapci commands in Stata (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993). Sensitivity and specificity of GP diagnoses were calculated taking GDS, HADS and SCID as reference standards. For sensitivity and specificity of GDS and HADS diagnoses the SCID was set as a reference standard. Furthermore, three multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed in order to compare the GP diagnosis with the combination of GDS (model I), HADS (model II) and SCID (model III), and to identify factors that are associated with the different depression diagnoses. Each model included a dependent variable with four values representing any combination of the GP diagnosis with the diagnosis of one of the three depression instruments. For example, model I distinguished between “no depression diagnosis” (scored 1), “GP diagnosis only” (scored 2), “GDS diagnosis only” (scored 3), and “GP diagnosis and GDS diagnosis” (scored 4). The GPs' age, gender and professional experience (work experience, psychiatric/psychotherapeutic training and experience in treatment of mental illnesses) were included into the three models as GP‐related predictors. The patients' age, gender, education, marital status, ADL/IADL score, CDS, self‐rated health, intake of chemical antidepressants, MMSE, HADS anxiety subscale and social support were included as patient‐related predictor variables. In order to test the model specification the Hausman test was applied, revealing that the assumption of the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) was not violated in either model. In addition, all predictors were tested for multicollinearity, showing negligible relations between predictors. Relative risk ratios (RRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. In all analyses, a p‐value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Socio‐demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows socio‐demographic and clinical characteristics of the total study sample, the subsamples of depressive patients according to the four diagnostic options and the subsample of patients who did not receive any depression diagnosis. According to the GPs 24.3% of the patients were diagnosed with depression. The proportion of patient‐reported depression was 21.8% for the GDS, 18.9% for the HADS and 8.2% for the SCID (minor and major depression). About 58% had no diagnosis of depression.

Table 1.

Socio‐demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient sample by diagnostic options

| Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | GP diagnosis | GDS > 4 | HADS >7 | SCID diagnosis | 4 diagnosesa | No diagnosisa | |

| Overall (n, (%)) | 1,113 (100.0) | 271 (24.3) | 243 (21.8) | 210 (18.9) | 91 (8.2) | 38 (3.4) | 650 (58.4) |

| Age (in years) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 80.7 (4.5) | 80.9 (4.6) | 81.08 (4.8) | 81.7 (4.9) | 80.7 (4.5) | 81.4 (5.0) | 80.4 (4.5) |

| Age groups (n, (%)) | |||||||

| 75–79 | 545 (49.0) | 132 (48.7) | 110 (45.3) | 84 (40.0) | 45 (49.5) | 17 (44.7) | 336 (51.7) |

| 80–84 | 336 (30.2) | 77 (28.4) | 76 (31.3) | 69 (32.9) | 30 (33.0) | 11 (28.9) | 188 (28.9) |

| ≥ 85 | 232 (20.8) | 62 (22.9) | 57 (23.5) | 57 (27.1) | 16 (17.6) | 10 (26.3) | 126 (19.4) |

| Gender (n, (%)) | |||||||

| Male | 417 (37.5) | 54 (19.9) | 69 (28.4) | 66 (31.4) | 18 (19.8) | 6 (15.8) | 298 (45.8) |

| Female | 696 (62.5) | 217 (80.1) | 174 (71.6) | 144 (68.6) | 73 (80.2) | 32 (84.2) | 352 (54.2) |

| Education b (n, (%)) | |||||||

| High | 200 (18.0) | 34 (12.5) | 30 (12.3) | 27 (12.9) | 9 (9.9) | 6 (15.8) | 139 (21.4) |

| Middle | 292 (26.2) | 60 (22.1) | 72 (29.6) | 59 (28.1) | 16 (17.6) | 7 (18.4) | 177 (27.2) |

| Low | 615 (55.3) | 173 (63.8) | 141 (58.0) | 124 (59.0) | 65 (71.4) | 25 (65.8) | 332 (51.1) |

| Marital status b (n, (%)) | |||||||

| Married/with | 515 (46.3) | 102 (37.6) | 87 (35.8) | 70 (33.3) | 32 (35.2) | 7 (18.4) | 337 (51.8) |

| Spouse married/living apart | 22 (2.0) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (4.4) | 2 (5.3) | 16 (2.5) |

| Single | 47 (4.2) | 15 (5.5) | 5 (2.1) | 8 (3.8) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | 28 (4.3) |

| Divorced | 62 (5.6) | 17 (6.3) | 17 (7.0) | 17 (8.1) | 9 (9.9) | 5 (13.2) | 32 (4.9) |

| Widowed | 466 (41.9) | 134 (49.4) | 129 (53.1) | 112 (53.3) | 44 (48.4) |

23 (60.5) |

236 (36.3) |

| IADL c (n, (%)) | |||||||

| Yes (impaired) | 700 (62.9) | 201 (74.2) | 200 (82.3) | 176 (83.8) | 72 (79.1) | 31 (81.6) | 348 (53.5) |

| No (unimpaired) | 413 (37.1) | 70 (25.8) | 43 (17.7) | 34 (16.2) | 19 (20.9) | 7 (18.4) | 302 (46.5) |

| CDS d (mean (SD)) | 5.1 (2.9) | 5.0 (3.0) | 5.8 (3.0) | 5.7 (2.9) | 5.3 (3.3) | 5.1 (3.4) | 4.9 (2.8) |

| VAS EQ‐5D e (mean (SD)) | 66.8 (19.1) | 62.2 (19.9) | 53.6 (18.9) | 56.1 (19.5) | 56.8 (22.0) | 48.2 (22.5) | 71.7 (16.8) |

| Intake of antidepressants f (n, (%)) | |||||||

| Yes | 144 (12.9) | 103 (38.0) | 54 (22.2) | 44 (21.0) | 27 (29.7) | 23 (60.5) | 25 (3.8) |

| No | 935 (84.0) | 160 (59.0) | 180 (74.1) | 155 (73.8) | 61 (67.0) | 13 (34.2) | 606 (93.2) |

| MMSE g (mean (SD)) | 27.3 (2.3) | 26.9 (2.7) | 26.7 (2.6) | 27.1 (2.5) | 27.1 (2.4) | 26.7 (2.5) | 27.6 (2.1) |

| HADS anxiety (mean (SD)) | 4.6 (3.2) | 6.2 (3.7) | 7.1 (3.7) | 7.1 (3.7) | 8.7 (3.8) | 9.7 (4.2) | 3.6 (2.5) |

| ESSI h (n, (%)) | |||||||

| High | 885 (79.5) | 195 (72.0) | 164 (67.5) | 137 (65.2) | 58 (63.7) | 20 (52.6) | 555 (85.4) |

| Low | 206 (18.5) | 69 (25.5) | 71 (29.2) | 67 (31.9) | 31 (34.1) | 17 (44.7) | 83 (12.8) |

Note: GP, general practitioner; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV; SD, standard deviation.

Depression according to GP, GDS, HADS and SCID. No depression according to GP, GDS, HADS and SCID.

n = 1107, educational classification according to the new CASMIN educational classification (Brauns & Steinmann, 1999). Low = inadequately completed general education, general elementary education, basic vocational qualification or general elementary education and vocational qualification; Middle = intermediate vocational qualification or intermediate general qualification and vocational qualification, intermediate general qualification, general maturity certificate, vocational maturity certificate/general maturity certificate and vocational qualification; High = lower tertiary education – general diplomas/diplomas with vocational emphasis, higher tertiary education – lower level/higher level.

n = 1112.

IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

n = 1079, CDS, chronic disease score.

n = 1108, VAS EQ‐5D, current state of health/visual analogue scale.

n = 1079.

n = 1053; MMSE, mini‐mental‐state examination.

n = 1091, ESSI, enriched social support inventory.

The total sample of 1113 primary care patients included 62.5% women and had a mean age of 80.7 years (SD = 4.5). The number of female patients was approximately 10% higher in the subsamples diagnosed with depression by their GP or the SCID compared to the dimensional measures. The majority had a low educational level (55.3%), while in the subgroup of SCID diagnoses the number of patients with low education was highest (71.4%). Most of the patients were either married and living with spouse (46.3%) or widowed (41.9%). Remarkably, in the subgroup of patients with all four diagnoses the number of patients who were married was only 18.4%, while 60.5% were widowed. Almost two‐thirds (62.9%) of the patients were functionally impaired according to the IADL scale. Compared with the total sample, this amount was markedly higher in the depressed patients. The mean number of drugs taken for medical conditions was 5.1 (SD = 2.9). The average patients' state of health using the VAS EQ‐5D was 66.8 (SD = 19.1) and was about 13 points lower in the subgroup with a GDS diagnosis of depression. About 13% of the total sample was treated with antidepressants. In the subsample of patients diagnosed with depression by their GP, 38% reported intake of antidepressants, while about one in five patients diagnosed with the GDS or HADS received antidepressants. The mean score of the MMSE in the total study sample was 27.3 (SD = 2.3) and the average anxiety score was 4.6 (SD = 3.2). While MMSE scores in the subgroups with a depression diagnosis were comparable to the total sample and to the subsample without a depression diagnosis, anxiety scores were higher, ranging from 6.2 (GP diagnosis) to 8.7 (SCID diagnosis). The majority of the patients reported high social support. While 18.5% of the total sample was lacking social support, this amount was markedly higher in the different subgroups with a depression diagnosis. Most notably, patients with a SCID diagnosis (34.1%) and patients with all four diagnoses (44.7%) reported low social support.

3.2. Agreement of depression diagnoses

Table 2 shows pairwise comparisons of the different measures for the diagnosis of depression. Agreement between GP diagnosis of depression and the three depression tools was slight in all cases: K = 0.28 for the GDS, K = 0.26 for the HADS and K = 0.22 for the SCID (Altman, 1991). The screening tools showed moderate agreement (K = 0.51). SCID and screening tools showed a slight agreement, i.e. K = 0.28 for the GDS and K = 0.31 for the HADS.

Table 2.

Agreement of depression diagnoses by Cohen's kappa

| Comparison of diagnoses | Kappa (95% CI) | a | N (%) | Sensitivity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity (95% CI) | ||||

| GP versus GDS | 0.28 (0.22; 0.35) | −/− | 714 (64.2) | Reference standard: |

| +/+ | 115 (10.3) | GDS | ||

| −/+ | 128 (11.5) | 0.47 (0.41; 0.54) | ||

| +/− | 156 (14.0) | 0.82 (0.79; 0.85) | ||

| GP versus HADS | 0.26 (0.19; 0.32) | −/− | 732 (65.8) | Reference standard: |

| +/+ | 100 (9.0) | HADS | ||

| −/+ | 110 (9.9) | 0.48 (0.41; 0.55) | ||

| +/− | 171 (15.4) | 0.81 (0.78; 0.84) | ||

| GP versus SCID | 0.22 (0.16; 0.28) | −/− | 808 (72.6) | Reference standard: |

| +/+ | 57 (5.1) | SCID | ||

| −/+ | 34 (3.1) | 0.63 (0.52; 0.73) | ||

| +/− | 214 (19.2) | 0.79 (0.76; 0.82) | ||

| GDS versus HADS | 0.51 (0.45; 0.57) | −/− | 798 (71.7) | − |

| +/+ | 138 (12.4) | |||

| −/+ | 72 (6.5) | |||

| +/− | 105 (9.4) | |||

| GDS versus SCID | 0.28 (0.21; 0.35) | −/− | 840 (75.5) | Reference standard: |

| +/+ | 61 (5.5) | SCID | ||

| −/+ | 30 (2.7) | 0.67 (0.56; 0.77) | ||

| +/− | 182 (16.4) | 0.82 (0.80; 0.84) | ||

| HADS versus SCID | 0.31 (0.23; 0.38) | −/− | 870 (78.2) | Reference standard: |

| +/+ | 58 (5.2) | SCID | ||

| −/+ | 33 (3.0) | 0.64 (0.53; 0.74) | ||

| +/− | 152 (13.7) | 0.85 (0.83; 0.87) |

Note: CI, confidence interval; GP, general practitioner; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale, cutoff >4; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, cutoff >7; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV.

+ indicates a positive diagnosis; − indicates a negative diagnosis. Consequently, −/− and +/+ indicate agreement between diagnoses; −/+ and +/− indicate disagreement between diagnoses.

Sensitivity of GP diagnosis was 0.47 for the GDS, 0.48 for the HADS and 0.63 for the SCID. The number of patients who were not recognized as depressed by their GP was 11.5% for the GDS, 9.9% for the HADS and 3.1% for the SCID. Specificity of GP diagnosis was 0.82 for the GDS, 0.81 for the HADS and 0.79 for the SCID. Screening tools reached sensitivity rates of 0.67 (GDS) and 0.64 (HADS) when compared to the SCID and specificity rates of 0.82 (GDS) and 0.85 (HADS).

3.3. Factors associated with depression diagnoses

3.3.1. Model I: General practitioner (GP) versus geriatric depression scale (GDS)

Table 3 presents factors that are associated with an exclusive GP, GDS, HADS or SCID diagnosis. In addition, it depicts factors that are associated with pairwise combinations of GP diagnoses and the three other diagnostic approaches.

Table 3.

Results of the multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting GP versus GDS, HADS and SCID

| RRR | 95% ci | RRR | 95% ci | RRR | 95% ci | Wald | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II GP/HADS | GPa (N = 137) | GDSb (N = 110) | GP & GDSc (N = 95) | |||||

| GP related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.95;1.06 | 1.01 | 0.95;1.08 | 0.97 | 0.90;1.04 | X 2 = 1.35 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Male | 1.35 | 0.85;2.13 | 0.97 | 0.59;1.60 | 1.03 | 0.59;1.79 | X 2 = 1.82 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Work experience | 0.97 | 0.92;1.02 | 0.99 | 0.93;1.05 | 1.01 | 0.94;1.08 | X 2 = 1.56 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Psychiatric/psycho‐therapeutic training | 1.29 | 0.82;2.03 | 0.74 | 0.44;1.22 | 0.70 | 0.39;1.23 | X 2 = 4.87 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Experience in treatment of mental illnesses | 1.62* | 1.05;2.51 | 0.95 | 0.59;1.56 | 1.60 | 0.94;2.74 | X 2 = 7.03 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Patient‐related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.03 | 0.98;1.08 | 1.02 | 0.97;1.08 | 1.01 | 0.95;1.07 | X 2 = 1.38 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Male | 0.38** | 0.22;0.66 | 1.02 | 0.59;1.77 | 0.81 | 0.43;1.56 | X 2 = 11.87 | p < 0.01 |

| Educationj | X 2 = 10.91 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Low | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Middle | 0.52* | 0.32;0.89 | 1.41 | 0.82;2.42 | 1.48 | 0.81;2.71 | ||

| High | 0.95 | 0.51;1.76 | 1.04 | 0.51;2.13 | 1.11 | 0.49;2.53 | ||

| Marital status | X 2 = 3.60 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Single/divorced | 1.48 | 0.73;3.01 | 1.04 | 0.43;2.48 | 0.98 | 0.38;2.51 | ||

| Widowed | 1.19 | 0.72;1.99 | 1.39 | 0.80;2.44 | 1.41 | 0.76;2.62 | ||

| IADL/ADL, impaired | 1.34 | 0.83;2.16 | 2.03* | 1.12;3.70 | 1.70 | 0.90;3.22 | X 2 = 7.27 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| CDS | 0.98 | 0.91;1.06 | 1.13** | 1.04;1.22 | 0.95 | 0.87;1.05 | X 2 = 12.31 | p < 0.01 |

| Vas EQ‐5D | 0.99 | 0.98;1.01 | 0.96*** | 0.94;0.97 | 0.95*** | 0.94;0.97 | X 2 = 65.51 | p < 0.001 |

| Intake of antidepressants | 13.90*** | 8.01;24.12 | 1.39 | 0.59;3.29 | 10.85*** | 5.55;21.23 | X 2 = 110.38 | p < 0.001 |

| MMSE | 1.00 | 0.90;1.10 | 0.92 | 0.84;1.01 | 0.92 | 0.83;1.02 | X 2 = 4.51 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| HADS anxiety subscale | 1.12** | 1.03;1.20 | 1.37*** | 1.27;1.49 | 1.44*** | 1.32;1.57 | X 2 = 87.44 | p < 0.001 |

| ESSI (high) | 1.17 | 0.66;2.05 | 1.96* | 1.12;3.42 | 1.88* | 1.01;3.53 | X 2 = 7.19 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| N | 989 | |||||||

| Nagelkerkes R 2 | 0.26 | |||||||

| Log likelihood | −743.28 | |||||||

| Model II GP/HADS | GP d (N = 148) | HADS e (N = 93) | GP & HADS f (N = 84) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.97 | 0.92;1.03 | 1.00 | 0.93;1.06 | 1.03 | 0.96;1.10 | X 2 = 2.13 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Male | 1.31 | 0.85;2.03 | 0.70 | 0.42;1.17 | 0.81 | 0.45;1.47 | X 2 = 4.57 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Work experience | 1.01 | 0.96;1.07 | 1.03 | 0.96;1.09 | 0.95 | 0.89;1.01 | X 2 = 3.92 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Psychiatric/psycho‐therapeutic training | 1.22 | 0.79;1.89 | 1.00 | 0.60;1.66 | 0.82 | 0.45;1.48 | X 2 = 1.63 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Experience in treatment of mental illnesses | 1.53* | 1.01;2.31 | 0.88 | 0.53;1.45 | 1.84* | 1.05;3.24 | X 2 = 7.94 | p < 0.05 |

| Patient‐related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.97;1.07 | 1.08** | 1.03;1.14 | 1.05 | 0.99;1.12 | X 2 = 10.11 | p < 0.05 |

| Male | 0.42** | 0.25;0.72 | 2.11** | 1.21;3.68 | 1.04 | 0.52;2.09 | X 2 = 19.58 | p < 0.001 |

| Educationj | X 2 = 6.55 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Low | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Middle | 0.57* | 0.34;0.95 | 0.84 | 0.48;1.49 | 1.14 | 0.61;2.15 | ||

| High | 0.99 | 0.55;1.79 | 0.83 | 0.41;1.69 | 0.83 | 0.34;2.02 | ||

| Marital status | X 2 = 7.29 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Single/divorced | 1.45 | 0.72;2.92 | 2.22 | 0.95;5.16 | 1.53 | 0.60;3.92 | ||

| Widowed | 1.23 | 0.76;1.99 | 1.99* | 1.12;3.55 | 1.41 | 0.73;2.71 | ||

| IADL/ADL | 1.21 | 0.77;1.91 | 2.15* | 1.17;3.98 | 2.18* | 1.08;4.39 | X 2 = 9.62 | p < 0.05 |

| CDS | 0.99 | 0.92;1.06 | 1.12** | 1.03;1.22 | 0.91 | 0.83;1.01 | X 2 = 12.63 | p < 0.01 |

| Vas EQ‐5D | 0.99 | 0.98;1.00 | 0.98** | 0.97;0.99 | 0.97*** | 0.95;0.98 | X 2 = 25.49 | p < 0.001 |

| Intake of antidepressants | 12.27*** | 7.31;20.58 | 0.89 | 0.32;2.48 | 10.21*** | 5.20;20.08 | X 2 = 110.67 | p < 0.001 |

| MMSE | 1.00 | 0.91;1.09 | 1.13* | 1.01;1.27 | 1.02 | 0.91;1.15 | X 2 = 4.85 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| HADS anxiety subscale | 1.08* | 1.01;1.16 | 1.30*** | 1.20;1.41 | 1.44*** | 1.32;1.58 | X 2 = 79.86 | p < 0.001 |

| ESSI (high) | 1.04 | 0.60;1.79 | 1.91* | 1.09;3.36 | 1.98* | 1.05;3.75 | X 2 = 8.22 | p < 0.05 |

| N | 989 | |||||||

| Nagelkerkes R 2 | 0.24 | |||||||

| Log likelihood | −742.96 | |||||||

| Model III GP/SCID | GP g (N = 188) | SCID h (N = 27) | GP & SCID i (N = 44) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.96;1.06 | 0.96 | 0.85;1.09 | 0.83** | 0.72;0.95 | X 2 = 8.10 | p < 0.05 |

| Male | 1.45 | 0.97;2.16 | 3.80** | 1.43;10.10 | 0.51 | 0.22;1.20 | X 2 = 14.08 | p < 0.01 |

| Work experience | 0.97 | 0.93;1.01 | 1.02 | 0.91;1.14 | 1.19* | 1.04;1.36 | X 2 = 10.13 | p < 0.05 |

| Psychiatric/psycho‐therapeutic training | 1.22 | 0.82;1.82 | 2.04 | 0.85;4.87 | 0.66 | 0.29;1.50 | X 2 = 5.02 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Experience in treatment of mental illnesses | 1.73** | 1.19;2.54 | 1.76 | 0.74;4.14 | 1.38 | 0.64;2.98 | X 2 = 8.95 | p < 0.05 |

| Patient‐related variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98;1.06 | 1.05 | 0.95;1.16 | 1.04 | 0.96;1.14 | X 2 = 2.01 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Male | 0.52** | 0.33;0.83 | 0.99 | 0.39;2.55 | 0.33 | 0.11;1.02 | X 2 = 10.09 | p < 0.05 |

| Educationj | X 2 = 4.89 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Low | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Middle | 0.70 | 0.45;1.10 | 0.44 | 0.15;1.30 | 0.83 | 0.33,2.06 | ||

| High | 0.95 | 0.55;1.63 | 0.47 | 0.11;1.90 | 1.02 | 0.30;3.52 | ||

| Marital status | X 2 = 4.83 | p ≥ 0.05 | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Single/divorced | 1.07 | 0.55;2.07 | 0.38 | 0.04;3.35 | 2.94 | 0.94;9.18 | ||

| Widowed | 1.10 | 0.71;1.72 | 0.82 | 0.32;2.14 | 1.46 | 0.58;3.65 | ||

| IADL/ADL | 1.27 | 0.83;1.93 | 0.80 | 0.31;2.06 | 1.70 | 0.63;4.59 | X 2 = 2.34 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| CDS | 0.94 | 0.88;1.00 | 1.00 | 0.85;1.16 | 0.98 | 0.86;1.11 | X 2 = 3.39 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| Vas EQ‐5D | 0.99 | 0.98;1.00 | 0.99 | 0.97;1.02 | 0.97*** | 0.95;0.99 | X 2 = 13.65 | p < 0.01 |

| Intake of antidepressants | 11.65*** | 7.17;18.93 | 1.03 | 0.21;5.06 | 15.74*** | 6.77;36.58 | X 2 = 112.35 | p < 0.001 |

| MMSE | 0.98 | 0.91;1.06 | 1.10 | 0.90;1.34 | 1.07 | 0.90;1.26 | X 2 = 1.82 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| HADS anxiety subscale | 1.12** | 1.05;1.19 | 1.44*** | 1.27;1.63 | 1.49*** | 1.32;1.67 | X 2 = 65.46 | p < 0.001 |

| ESSI (high) | 1.16 | 0.72;1.87 | 1.52 | 0.59;3.94 | 1.48 | 0.64;3.43 | X 2 = 1.49 | p ≥ 0.05 |

| N | 989 | |||||||

| Nagelkerkes R 2 | 0.25 | |||||||

| Log likelihood | −575.90 | |||||||

Note: GP, general practitioner; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV criteria; RRR, relative risk ratio; CI, confidence interval; IADL/ADL, (instrumental) activities of daily living; CDS, chronic disease score; VAS EQ‐5D, current state of health/visual analogue scale; MMSE, mini‐mental‐state examination; ESSI, Enriched Social Support Inventory.

GP: Depression diagnosis according to GP but not to GDS.

GDS: Depression diagnosis according to GDS but not to GP.

GP & GDS: Depression diagnosis according to both GP and GDS; Base category: No depression diagnosis according to GP and GDS.

GP: Depression diagnosis according to GP but not to HADS.

HADS: Depression diagnosis according to HADS but not to GP.

GP & HADS: Depression diagnosis according to both GP and HADS; Base category: No depression diagnosis according to GP and HADS.

GP: Depression diagnosis according to GP but not to SCID.

SCID: Depression diagnosis according to SCID but not to GP.

GP & SCID: Depression diagnosis according to both GP and SCID; Base category: No depression diagnosis according to GP and SCID.

Educational classification according to the new CASMIN educational classification (Brauns & Steinmann, 1999).

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

The comparison between GP and GDS diagnoses shows that females had a 1/0.38 = 2.6 times higher relative risk of being diagnosed by the GP alone than males. Patients with a higher CDS, that is, patients reporting more medication use, had a higher relative risk of getting an exclusive GDS diagnosis. Furthermore, patients reporting better health were less likely to score positive exclusively on the GDS (RRR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94–0.97) and less likely to receive both diagnoses (RRR = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.94–0.97), compared to patients receiving neither a GP nor a GDS diagnosis. In addition, patients treated with antidepressants were more likely diagnosed as depressed by their GP (RRR = 13.90; 95% CI: 8.01–24.12) and had a higher relative risk of receiving both a GP and a GDS diagnosis. Patients reporting higher levels of anxiety had an increased risk of a depression diagnosis according to their GP; the risk was even higher in those being diagnosed exclusively with the GDS and highest in those getting both diagnoses (RRR = 1.44; 95% CI: 1.32–1.57).

3.3.2. Model II: General practitioner (GP) versus hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

Findings were similar to those observed in model I. However, social support and functional impairment increased the likelihood of getting a HADS diagnosis and the combination of HADS and GP diagnosis. Older patients were more likely to receive an exclusive HADS diagnosis. Moreover, the GPs' experience in treatment of mental illnesses emerged as a significant predictor, as it was associated with an exclusive GP diagnosis and with the combination of GP and HADS. Hence, given that the GP has experience in treating mental illness; patients are more likely being diagnosed by their GP, and being additionally screened positive using the HADS.

3.3.3. Model III: General practitioner (GP) versus structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV (SCID)

Model III did not reveal any additional patient‐related variables, as only gender, intake of antidepressants, current state of health and anxiety emerged as significant factors. However, some additional GP related variables were associated with the likelihood of getting a depression diagnosis. For example, a lower age and a longer work experience of the GP increased the likelihood of patients to receive both a GP and a SCID diagnosis.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Agreement of depression diagnoses by diagnostic option

In view of GP diagnoses, we found high specificity compared to both the dimensional and the categorical perspective, but lower sensitivity. Hence, GPs performed better in ruling out depression than ruling in depression, which is consistent with the findings of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (Cepoiu et al., 2008; Mitchell, Vaze, & Rao, 2009). A comparable result was seen for screening tools when compared with a gold standard diagnosis (SCID). GPs identified about half of the cases as depressed who had a diagnosis according to a screening tool and recognized slightly more of those patients with a gold standard diagnosis. The agreement between the perspectives of GPs, dimensional and categorical approaches was only slight indicating that the approaches provide different information for the diagnosis of depression. This finding is consistent with a study of Schwarzbach et al. (2014) who compared the agreement of GDS and GPs in a cohort of multimorbid elderly patients, suggesting that GDS and GPs are sensitive to different variables. The gap between categorical and dimensional approaches is consistent with other studies in this field. For example, a study using the same cutoff for the HADS documented that the prevalence of depression was 18% in patients aged 70 and older (Stordal et al., 2001). Studies using the GDS to evaluate depressive symptoms in elderly patients report prevalence rates between 9.6% and 37.4% (Al‐Shammari & Al‐Subaie, 1999; Murata, Kondo, Hirai, Ichida, & Ojima, 2008; Wong, Mercer, Woo, & Leung, 2008). In contrast, prevalence rates according to categorical measures are substantially lower. According to a systematic review and a meta‐analysis, categorical instruments yield prevalence rates of current depression in the elderly between 3.3% (Volkert, Schulz, Härter, Wlodarczyk, & Andreas, 2013) and 7.2% (Luppa, Sikorski, Luck et al., 2012), while dimensional depression rates range from 17.1% (Luppa, Sikorski, Luck et al., 2012) to 19.5% (Volkert et al., 2013). The agreement between dimensional and categorical perspectives may be low, because screening tools identify patients at risk of having a clinical depression and therefore also consider those patients with subthreshold depression, while categorical tools detect only those patients with clinical depression.

4.2. Associated factors of depression diagnoses

The GP's experience in treating mental illnesses was associated with a GP diagnosis of depression. This finding is supported by a study of Anthony et al. (2010), showing that primary care clinicians felt more confident in recognizing and managing depression if they had trained with a psychologist/psychiatrist or had already worked in psychiatry. In addition, clinicians were more likely to refer a depressed patient to a mental health specialist when they felt comfortable in prescribing antidepressants and counselling patients with depression. Hence, the GP's professional experience seems to have a substantial impact on both diagnostic accuracy and management of depression. Interestingly, about one in five patients was diagnosed with depression by their GP even if they did not score on the SCID. On the one hand, one could argue that GPs in our study tended to over‐diagnose depression. On the other hand, the likelihood of receiving a GP diagnosis in the absence of a SCID diagnosis was increased when GPs reported to have experience in the treatment of mental illnesses. Therefore, one could also assume under‐diagnosis by the SCID.

A relevant patient‐based factor for the diagnosis of depression was the intake of antidepressants. Patients who reported to take antidepressants were more likely to receive a depression diagnosis by their GP. This finding is obvious, since the GPs most likely prescribed antidepressants based on a preceding depression diagnosis. Furthermore, drug‐treated patients presenting with a GP diagnosis were also more likely to additionally score on the instruments. This in turn supports the validity of the GP diagnosis. In a systematic review and meta‐analysis Mottram, Wilson, and Strobl (2006) suggested that prescribing antidepressants is an effective treatment option in managing depression in the elderly. However, practitioners need to be aware of side effects and interactions with other medication (Mark et al., 2011).

Moreover, the presence of current symptoms of anxiety was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving depression diagnoses according to either diagnostic option. In line with our results, Mergl et al. (2007) found strong associations between depression and anxiety, arguing that there may be a dimensional link between these disorders. A study on recognition of depression in primary care (Wittchen & Pittrow, 2002) showed that 19% of depressed patients were assigned a diagnosis of another mental disorder instead of depression, particularly anxiety disorder or psychosomatic illness.

A further patient‐related factor for depression diagnostics was gender. We found that female gender increased the likelihood of receiving a GP diagnosis of depression. This finding is supported by the results of Maske et al. (2016), who reported that female gender was correlated with DSM‐IV major depression, self‐reported diagnosed depression and current depressive symptoms. Moreover, higher prevalence rates of depressive disorders in women compared to men were reported by a large epidemiological survey examining the German adult population (DEGS1). Here, the 12‐months prevalence of major depression was 8% for females compared to 3% for males (Jacobi et al., 2014).

The presence of somatic complaints might interfere with depression diagnosis in elderly primary care patients (Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009). However, the assumption that depression in physically impaired patients may not be recognized due to focus on somatic rather than mental problems has been rejected by several authors (Ani et al., 2008; Tai‐Seale et al., 2005). In our study, patients reporting functional impairment were more likely to receive an exclusive HADS diagnosis and a lower state of health increased the likelihood to receive a sole GDS or HADS diagnosis, suggesting that these measures are sensitive in detecting depression in patients with physical complaints. This is a striking result as both instruments preclude physically confounded symptoms. The fact that functional impairment and current state of health were not associated with receiving an exclusive GP diagnosis or SCID diagnosis indicates that the different diagnostic options for depressive disorders identify different individuals as depressed. This assumption is additionally supported by the findings showing that a higher chronic disease score was associated with an exclusive GDS and HADS diagnosis and social support was associated with HADS diagnostics but not with the other measures.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study were the multicenter approach and a large sample of elderly primary care patients. However, this study is not without limitations. The measurements were applied sequentially in a specific order. Therefore, we cannot preclude position effects on response behavior. However, as part of the patient survey mental status was assessed at the beginning of the interview to ensure a high level of attention and to minimize possible effects of fatigue that could distort cognitive performance of the patients. Cohen's Kappa was used to calculate interrater agreement on the presence of depression according to the different perspectives. Kappa represents the gold standard for interrater agreement concerning nominal data, but it has been criticized to underestimate agreement in case of unbalanced prevalences within rating categories (Feinstein & Cicchetti, 1990; Grouven, Bender, Ziegler, & Lange, 2007). Since “no depression” was much more frequent than “depression” in this sample, chances for agreement were lower. Therefore, results on agreement based on Kappa may be biased and should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the different perspectives on depression are based on different concepts which may also contribute to lower Kappa values and to a limited interpretation of these values. For a comprehensive interpretation of data, we presented classification tables, sensitivity and specificity in addition to Kappa values. Furthermore, the GPs were asked in a questionnaire whether or not patients were currently affected by unremitted depression according to ICD‐10 criteria. We believe that this is a more precise measure than taking diagnostic codes from medical records as these have been shown to underestimate the accuracy of the GP (Joling et al., 2011). We assume that this item represents the unassisted diagnosis by GPs, but we cannot preclude that they applied any additional tools to diagnose depression. Further, the recruitment strategy may have raised the GPs' awareness for depressive disorders, which may have led to over‐diagnosis of depression. Moreover, we did not consider whether patients who were identified as depressed by either perspective had a request for help and agreed with the diagnosis. This is an important prerequisite for subsequent treatment and is likely to affect compliance. Another limitation is that this study analyzes only cross‐sectional data and it was not possible to conduct sub‐analyses for urban and rural areas due to our study design. As poorer health has been shown to be associated with reduced study participation (Ganguli, Lytle, Reynolds, & Dodge, 1998; Golomb et al., 2012), we cannot rule out a selection bias due to non‐response. In a previous study, coronary heart disease patients with comorbid depression were found to be less likely to participate, resulting in rates of 6% of participants versus 19% of non‐participants with depression (Munkhaugen et al., 2016). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that patients suffering from severe depression had refused participation to a greater extent and may therefore be underrepresented in our study. This, in turn, may lead to lower sensitivity rates of GP diagnoses in our study, as GPs were found to perform better at ruling in severe cases compared to milder forms of depression (O'Connor, Rosewarne, & Bruce, 2001). Likewise, the agreement between dimensional and categorical tools according to our data may be underestimated. However, the prevalence rate of patients with major depression in our study (4.3%) does not deviate substantially from the pooled prevalence rate of major depression (7.2%) that was reported in a previous meta‐analysis investigating individuals at the age of 75 years and older (Luppa, Sikorski, Luck et al., 2012). We therefore assume that a bias due to non‐participation had a limited impact on the results of our study. Finally, our findings are limited to a German patient population therefore may not apply to other countries.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

GPs performed better at ruling out depression than ruling in depression. Hence, a considerable number of patients who were depressed according to dimensional or categorical perspectives were missed out by GPs. In addition, results indicate slight agreement of depression diagnoses between GPs, dimensional and categorical tools. Likewise, the proportion of depressed patients in this study varied considerably, ranging between 8.2% and 24.3% for SCID and GP, respectively. As dimensional and categorical tools provide additional information, GPs should follow an assisted approach of depression diagnostics. Future studies should include non‐responder analyses to estimate the impact of bias due to non‐participation. Furthermore, future research may investigate the feasibility of an assisted diagnostic approach in primary care as well as the potential benefit. Patients taking antidepressants or medication to treat chronic diseases, those with symptoms of anxiety, a low state of health or functional impairment should be given particular attention.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant number: 01GY1155A). The authors would like to thank all primary care patients and GPs for their participation and cooperation.

Dorow M, Stein J, Pabst A, et al. Categorical and dimensional perspectives on depression in elderly primary care patients – Results of the AgeMooDe study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27:e1577 10.1002/mpr.1577

REFERENCES

- Almeida, O. P. , & Almeida, S. A. (1999). Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: A study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD‐10 and DSM‐IV. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(10), 858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Shammari, S. A. , & Al‐Subaie, A. (1999). Prevalence and correlates of depression among Saudi elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(9), 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D. G. (1991). Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ani, C. , Bazargan, M. , Hindman, D. , Bell, D. , Farooq, M. A. , Akhanjee, L. , … Rodriguez, M. (2008). Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: Discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settings. BMC Family Practice, 9, 1–9. 10.1186/1471-2296-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, J. S. , Baik, S.‐Y. , Bowers, B. J. , Tidjani, B. , Jacobson, C. J. , & Susman, J. (2010). Conditions that influence a primary care clinician's decision to refer patients for depression care. Rehabilitation Nursing: The Official Journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, 35(3), 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauns, H. , & Steinmann, S. (1999). Educational reform in France, West‐Germany and the United Kingdom: Updating the CASMIN educational classification. ZUMA Nachrichten, 23(44), 7–44. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 37(1), 53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepoiu, M. , McCusker, J. , Cole, M. G. , Sewitch, M. , Belzile, E. , & Ciampi, A. (2008). Recognition of depression by non‐psychiatric physicians – A systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(1), 25–36. 10.1007/s11606-007-0428-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN), Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF), & Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ) . (2015). S3‐Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression. Langfassung. 2. Auflage, Version 3. http://www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/depression/depression-2aufl-vers3-lang.pdf

- Efron, B. , & Tibshirani, R. J. (1993). An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- ENRICHD‐Investigators (2000). Enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (ENRICHD): Study design and methods. The ENRICHD investigators. American Heart Journal, 139(1 Pt 1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, A. R. , & Cicchetti, D. V. (1990). High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 43(6), 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, A. , Wetherell, J. L. , & Gatz, M. (2009). Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 363–389. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M. F. , Folstein, S. E. , & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini‐mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli, M. , Lytle, M. E. , Reynolds, M. D. , & Dodge, H. H. (1998). Random versus volunteer selection for a community‐based study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 53(1), M39–M46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauggel, S. , & Birkner, B. (1999). Validität und Reliabilität einer deutschen Version der Geriatrischen Depressionsskala (GDS). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 28, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Golomb, B. A. , Chan, V. T. , Evans, M. A. , Koperski, S. , White, H. L. , & Criqui, M. H. (2012). The older the better: Are elderly study participants more non‐representative? A cross‐sectional analysis of clinical trial and observational study samples. BMJ Open, 2(6). e000833. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouven, U. , Bender, R. , Ziegler, A. , & Lange, S. (2007). Der Kappa‐Koeffizient [The kappa coefficient]. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946), 132(Suppl 1), e65–e68. 10.1055/s-2007-959046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühne, U. , Luppa, M. , Stein, J. , Wiese, B. , Weyerer, S. , Maier, W. , … Riedel‐Heller, S. G. (2016). Barriers and opportunities for optimized treatment of late life depression “Die vergessenen Patienten” – Barrieren und Chancen einer optimierten Behandlung depressiver Erkrankungen im Alter. Psychiatrische Praxis, 43(7), 387–394. 10.1055/s-0035-1552639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühne, U. , Stein, J. , & Riedel‐Heller, S. (2016). Depression in old age – Challenge of an ageing society [depression im Alter – Herausforderung langlebiger Gesellschaften]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 42(2), 107–110. 10.1055/s-0035-1552661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman, J. S. , Veazie, P. J. , & Lyness, J. M. (2006). Primary care physician office visits for depression by older Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(9), 926–930. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00497.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, C. , Buss, U. , & Snaith, R. P. (1995). HADS‐D – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Deutsche Version. Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Angst und Depressivität in der somatischen Medizin. Bern: Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Holvast, F. , Verhaak, P. F. M. , Dekker, J. H. , de Waal, M. W. M. , van Marwijk, H. W. J. , Penninx, B. W. J. H. , & Comijs, H. (2012). Determinants of receiving mental health care for depression in older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 143(1–3), 69–74. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi, F. , Höfler, M. , Strehle, J. , Mack, S. , Gerschler, A. , Scholl, L. , … Wittchen, H.‐U. (2014). Psychische Störungen in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. Der Nervenarzt, 85(1), 77–87. 10.1007/s00115-013-3961-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joling, K. J. , van Marwijk, H. W. J. , Piek, E. , van der Horst, H. E. , Penninx, B. W. , Verhaak, P. , & van Hout, H. P. J. (2011). Do GPs' medical records demonstrate a good recognition of depression? A new perspective on case extraction. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(3), 522–527. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendel, F. , Spaderna, H. , Sieverding, M. , Dunkel, A. , Lehmkuhl, E. , Hetzer, R. , & Regitz‐Zagrosek, V. (2011). Eine deutsche adaptation des ENRICHD social support inventory (ESSI). Diagnostica, 57(2), 99–106. 10.1026/0012-1924/a000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kivelitz, L. , Watzke, B. , Schulz, H. , Härter, M. , & Melchior, H. (2015). Health care barriers on the pathways of patients with anxiety and depressive disorders – A qualitative interview study [Versorgungsbarrieren auf den Behandlungswegen von Patienten mit angst‐ und depressiven Erkrankungen – Eine qualitative Interviewstudie]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 42(8), 424–429. 10.1055/s-0034-1370306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, S. , Verhey, F. , Weyerer, S. , Wiese, B. , Heser, K. , Wagner, M. , … Maier, W. (2013). Depression, non‐fatal stroke and all‐cause mortality in old age: A prospective cohort study of primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(1), 63–69. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korten, N. C. M. , Penninx, B. W. J. H. , Kok, R. M. , Stek, M. L. , Oude Voshaar, R. C. , Deeg, D. J. H. , & Comijs, H. C. (2014). Heterogeneity of late‐life depression: Relationship with cognitive functioning. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA, 26(6), 953–963. 10.1017/S1041610214000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppa, M. , Sikorski, C. , Luck, T. , Ehreke, L. , Konnopka, A. , Wiese, B. , … Riedel‐Heller, S. G. (2012). Age‐ and gender‐specific prevalence of depression in latest‐life – Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 212–221. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppa, M. , Sikorski, C. , Motzek, T. , Konnopka, A. , König, H.‐H. , & Riedel‐Heller, S. G. (2012). Health service utilization and costs of depressive symptoms in late life – A systematic review. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 18(36), 5936–5957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark, T. L. , Joish, V. N. , Hay, J. W. , Sheehan, D. V. , Johnston, S. S. , & Cao, Z. (2011). Antidepressant use in geriatric populations: The burden of side effects and interactions and their impact on adherence and costs. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(3), 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maske, U. E. , Buttery, A. K. , Beesdo‐Baum, K. , Riedel‐Heller, S. , Hapke, U. , & Busch, M. A. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of DSM‐IV‐TR major depressive disorder, self‐reported diagnosed depression and current depressive symptoms among adults in Germany. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 167–177. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergl, R. , Seidscheck, I. , Allgaier, A.‐K. , Möller, H.‐J. , Hegerl, U. , & Henkel, V. (2007). Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: Prevalence and recognition. Depression and Anxiety, 24(3), 185–195. 10.1002/da.20192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. J. , Bird, V. , Rizzo, M. , & Meader, N. (2010). Diagnostic validity and added value of the geriatric depression scale for depression in primary care: A meta‐analysis of GDS30 and GDS15. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1–3), 10–17. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. J. , Rao, S. , & Vaze, A. (2010). Do primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late‐life depression? A meta‐analysis stratified by age. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 79(5), 285–294. 10.1159/000318295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. J. , Vaze, A. , & Rao, S. (2009). Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: A meta‐analysis. Lancet, 374(9690), 609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, A. S. , Gilbody, S. , McMillan, D. , & Manea, L. (2015). Screening and case finding for major depressive disorder using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ‐9): A meta‐analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(6), 567–576. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram, P. , Wilson, K. , & Strobl, J. (2006). Antidepressants for depressed elderly. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1 CD003491. 10.1002/14651858.CD003491.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkhaugen, J. , Sverre, E. , Peersen, K. , Egge, Ø. , Gjertsen Eikeseth, C. , Gjertsen, E. , … Dammen, T. (2016). Patient characteristics and risk factors of participants and non‐participants in the NOR‐COR study. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal: SCJ, 50(5–6), 317–322. 10.1080/14017431.2016.1202445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata, C. , Kondo, K. , Hirai, H. , Ichida, Y. , & Ojima, T. (2008). Association between depression and socio‐economic status among community‐dwelling elderly in Japan: The Aichi Gerontological evaluation study (AGES). Health & Place, 14(3), 406–414. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, D. W. , Rosewarne, R. , & Bruce, A. (2001). Depression in primary care. 2: General practitioners' recognition of major depression in elderly patients. International Psychogeriatrics, 13(3), 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, S. D. , Foldager, L. , Allgulander, C. , Dahl, A. A. , Huuhtanen, M.‐T. , Rasmussen, I. , & Munk‐Jorgensen, P. (2010). Psychiatric caseness is a marker of major depressive episode in general practice. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 28(4), 211–215. 10.3109/02813432.2010.501235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignone, M. P. , Gaynes, B. N. , Rushton, J. L. , Burchell, C. M. , Orleans, C. T. , Mulrow, C. D. , & Lohr, K. N. (2002). Screening for depression in adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(10), 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocklington, C. , Gilbody, S. , Manea, L. , & McMillan, D. (2016). The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the geriatric depression scale: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(8), 837–857. 10.1002/gps.4407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel‐Heller, S. G. , Matschinger, H. , & Angermeyer, M. C. (2005). Mental disorders – Who and what might help? Help‐seeking and treatment preferences of the lay public. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(2), 167–174. 10.1007/s00127-005-0863-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth, U. , & Potthoff, P. (1993). Hilfe‐ und Pflegebedürftige in privaten Haushalten In Bericht zur Repräsentativerhebung im Forschungsprojekt “Möglichkeiten und Grenzen selbständiger Lebensführung”. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Schowalter, M. , Gelbrich, G. , Störk, S. , Langguth, J.‐P. , Morbach, C. , Ertl, G. , … Angermann, C. E. (2013). Generic and disease‐specific health‐related quality of life in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: Impact of depression. Clinical Research in Cardiology: Official Journal of the German Cardiac Society, 102(4), 269–278. 10.1007/s00392-012-0531-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach, M. , Luppa, M. , Hansen, H. , König, H.‐H. , Gensichen, J. , Petersen, J. J. , … Riedel‐Heller, S. G. (2014). A comparison of GP and GDS diagnosis of depression in late life among multimorbid patients – Results of the MultiCare study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 168, 276–283. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, J. I. , & Yesavage, J. (1986). Geriatric depression scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sinyor, M. , Tan, L. P. L. , Schaffer, A. , Gallagher, D. , & Shulman, K. (2016). Suicide in the oldest old: An observational study and cluster analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(1), 33–40. 10.1002/gps.4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J. , Pabst, A. , Weyerer, S. , Werle, J. , Maier, W. , Heilmann, K. ,… Riedel‐Heller, S. G. (2016). The assessment of met and unmet care needs in the oldest old with and without depression using the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): Results of the AgeMooDe study. Journal of affective disorders, 193, 309–317. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stordal, E. , Bjartveit Krüger, M. , Dahl, N. H. , Krüger, O. , Mykletun, A. , & Dahl, A. A. (2001). Depression in relation to age and gender in the general population: The Nord‐Trondelag health study (HUNT). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104(3), 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai‐Seale, M. , Bramson, R. , Drukker, D. , Hurwicz, M.‐L. , Ory, M. , Tai‐Seale, T. , … Cook, M. A. (2005). Understanding primary care physicians' propensity to assess elderly patients for depression using interaction and survey data. Medical Care, 43(12), 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh, T. N. , & McIntyre, N. J. (1992). The mini‐mental state examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40(9), 922–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert, J. , Schulz, H. , Härter, M. , Wlodarczyk, O. , & Andreas, S. (2013). The prevalence of mental disorders in older people in western countries – A meta‐analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(1), 339–353. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. W. , Pignone, M. , Ramirez, G. , & Perez Stellato, C. (2002). Identifying depression in primary care: A literature synthesis of case‐finding instruments. General Hospital Psychiatry, 24(4), 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H.‐U. , & Pittrow, D. (2002). Prevalence, recognition and management of depression in primary care in Germany: The depression 2000 study. Human Psychopharmacology, 17(Suppl 1), 1–11. 10.1002/hup.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H.‐U. , Zaudig, M. , & Fydrich, T. (1997). Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM‐IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S. Y. S. , Mercer, S. W. , Woo, J. , & Leung, J. (2008). The influence of multi‐morbidity and self‐reported socio‐economic standing on the prevalence of depression in an elderly Hong Kong population. BMC Public Health, 8, 119 10.1186/1471-2458-8-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010). International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) (10th revision). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A. S. , & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]