Abstract

Mental health in China is of growing concern to both policy‐makers and researchers. The Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS) was conducted between July 2011 and March 2012 to assess the prevalence and risk factors of mental disorders in the context of recent economic growth and other socio‐demographic changes in Tianjin, a municipality of 13 million on China's eastern seaboard. A multistage cluster random sample selected using probability proportionate to size methods participated in a two‐phase screening procedure: 11,748 subjects 18 or older were screened for risk of psychopathology and then an enriched risk‐proportional subsample of 4,438 subjects was interviewed by psychiatrists using an expanded Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) Axis I disorders (SCID). The study also collected information about the impairment associated with mental disorders, mental health literacy, the stigmatization of mental disorders, and help‐seeking behavior for psychological problems. This paper provides a detailed overview of the study rationale, objectives, field procedures, and pattern of response. It highlights several of the methodological challenges of maintaining quality control of a complex epidemiological study in the Chinese setting, issues that are relevant to other community‐based epidemiological studies in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Keywords: China, cross‐sectional community survey, mental disorders, prevalence, two‐phase screening design

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last 30 years, China has undergone rapid economic growth and witnessed fast‐paced urbanization (Wang, Ma, & Zhao, 2014; Zhang & Song, 2003). The Tianjin Municipality (administratively equivalent to a Chinese province) is one of the most important engines of China's economic growth: from 1995 to 2010 the population increased by 40% (from 9.4 to 13.0 million), the proportion of the population that were immigrants from other regions of China increased 4.5‐fold (from 5.3% to 23.8%),. and the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) increased 7.5‐fold (from ¥9,769 to ¥72,994) (Tianjin Municipal Statistics Bureau and NBS Survey Office in Tianjin, 2011).

Rapid development has been associated with social problems (Phillips, Liu, & Zhang, 1999) that may lead to increased rates of mental illnesses (Hidaka, 2012; Lee et al., 2007), so China's economic transformation has presented difficult challenges for the Chinese mental health care system (Phillips, 2004; Xiang, Yu, Sartorius, Ungvari, & Chiu, 2012). The two national surveys of mental health in China conducted in 1982 (Twelve‐Region Psychiatric Epidemiological Study Work Group, 1986) and in 1993 (Zhang et al., 1998) are too old to reflect the effect of more recent social changes on the prevalence of mental disorders and do not consider the effect of uneven economic development in different parts of the country. Realizing this, the national government has recently recommended that provinces conduct mental health epidemiological studies every five years (Xiong & Phillips, 2016). Several regional surveys have been published (Li et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2009b; Shen et al., 2006; World Health Organization [WHO] World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004), but there has, as yet, been no epidemiological report from the Tianjin municipality. However, studies in Tianjin have shown that psychiatric services are unevenly distributed across different municipal districts and that some communities have no mental health services whatsoever (Du et al., 2010; Du & Zhang, 2014), so local epidemiological data are needed to formulate municipality‐specific policies for improving mental health services. To address this issue, the Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS) was conducted between July 2011 and March 2012. The objectives of the study were as follows:

Estimate the one‐month (“current”) and lifetime prevalence of DSM‐IV mental disorders and their socio‐demographic determinants in adults aged 18 years of age and older.

Assess the demographic and clinical characteristics, family history, quality of life, and level of disability in individuals affected by different types of mental disorders.

Assess mental health literacy and the level of the stigmatization of mentally ill individuals among community members.

Assess help‐seeking behavior for psychological problems across formal and informal care settings and the level of unmet need for mental health services among individuals with and without mental disorders.

The current paper provides a detailed overview of the sampling methods, instruments, and survey procedures used in the TJMHS.

2. STUDY DESIGN

2.1. Methodological considerations

To ensure the clinical validity of the final diagnoses, psychiatrists administered the Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) Axis I disorders (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002; Phillips & Liu, 2011) to selected adult community members. To maximize the use of relatively limited psychiatric manpower, we increased the proportion of individuals with mental disorders among individuals administered the SCID by using a two‐phase design (Li, Wang, & Phillips, 2010; Phillips et al., 2009b). The first screening phase used an expanded version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) to identify an enriched sample of individuals at risk of mental disorders; the second diagnostic phase involved the administration of the SCID to determine whether or not a DSM‐IV diagnosis was present. The results were then weighted back to the sample population (Tianjin adults 18 and over) to provide community‐based prevalence estimates. This approach was previously used successfully in a large, four‐province study by Phillips et al. (2009b).

2.2. Sample

The minimally required sample size (n) was calculated using the formula n = μα 2 p (1 − p)/δ 2, where μ α = the one‐sided magnitude of the confidence level (at α = 0.05, μ α = 1.96), p = expected proportion of the outcome of interest (the prevalence of schizophrenia – the least prevalent disorder of interest—estimated as 0.8% [Phillips et al., 2009b], was used), and δ = margin of error (δ = 0.8% × 0.2 = 0.0016). The calculated necessary minimum sample size was 11,909. To account for non‐response, the number of subjects to be approached was set 30% higher, at 15,482.

Multistage sampling methods were used to obtain a representative sample of adult, non‐institutionalized, community residents. In the first stage, two to four streets or townships were selected using the probability proportionate to size (PPS) sampling method from each of the 15 urban districts and three rural counties in Tianjin. In the second stage, one to four neighborhoods or villages (primary sampling units, PSUs) were chosen using the PPS method from each of the streets or townships. Next, the total expected sample for the survey was apportioned to each district and country based on their relative populations and the number of households required in each PSU (ranging from 30 to 300) was determined based on the proportion of the population in all PSUs in the district or country that resided in the specific PSU. Then selected households were identified by a simple random method: (1) all households in the PSU were enumerated and assigned sequential numbers (1, 2, 3, etc.); (2) the selection interval (“X”) was determined by dividing the total number of households in the PSU by the number of households required in the PSU; (3) a random number (“Y″) between 1 and X was selected using the Excel “randbetween(1,X)” function; (4) households with sequence numbers Y, Y + X, Y + 2X, Y + 3X, and so forth were selected as study households and each selected household was given a unique sequential study number (1001, 1002, 1003, etc.).

Finally, in each selected household one adult household resident was randomly selected to be a study participant: (1) all individuals in the household were listed sequentially by age by the interviewer; (2) the number of persons 18 and older who had lived in the household for at least half of the time over the prior six months—potential respondents—was determined and each of them was assigned a sequential number based on their age (1 for the eldest, 2 for the second eldest, etc.); (3) the interviewer then identified the sequence number of the subject who would be selected as the study respondent by consulting a table generated for the study with rows for the number of potential respondents in the household (1, 2, 3, etc.), columns with the last digit of the household's unique 4‐digit study number (0 to 9), and cells with randomly selected numbers ranging from 1 to the number of potential respondents (i.e. the row number).

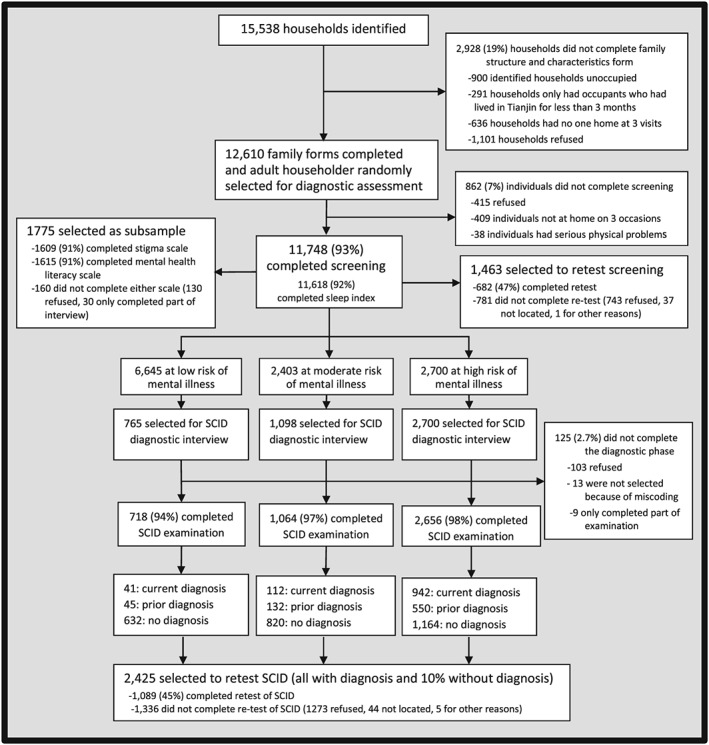

Using this procedure, 71 urban neighborhoods and 29 rural villages (i.e. 100 primary sampling sites) were identified and 15,538 households were selected, 11,573 from urban neighborhoods and 3,965 from rural villages. As shown in the flowchart for the study (Figures 1 and 2), 12,610 potential respondents were identified from these households and 11,748 of them completed the screening phase of the survey.

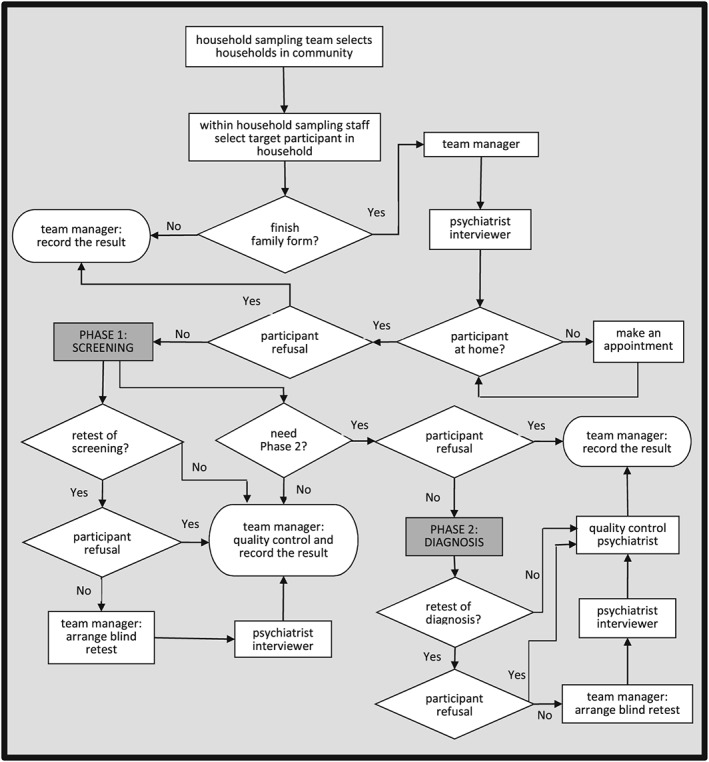

Figure 1.

Flowchart of fieldwork procedures of the Tianjin Mental Health Survey

Figure 2.

Flowchart of sampling results for the Tianjin Mental Health Survey

2.3. Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of Tianjin Mental Health Center. All respondents signed informed consent.

3. MEASUREMENTS

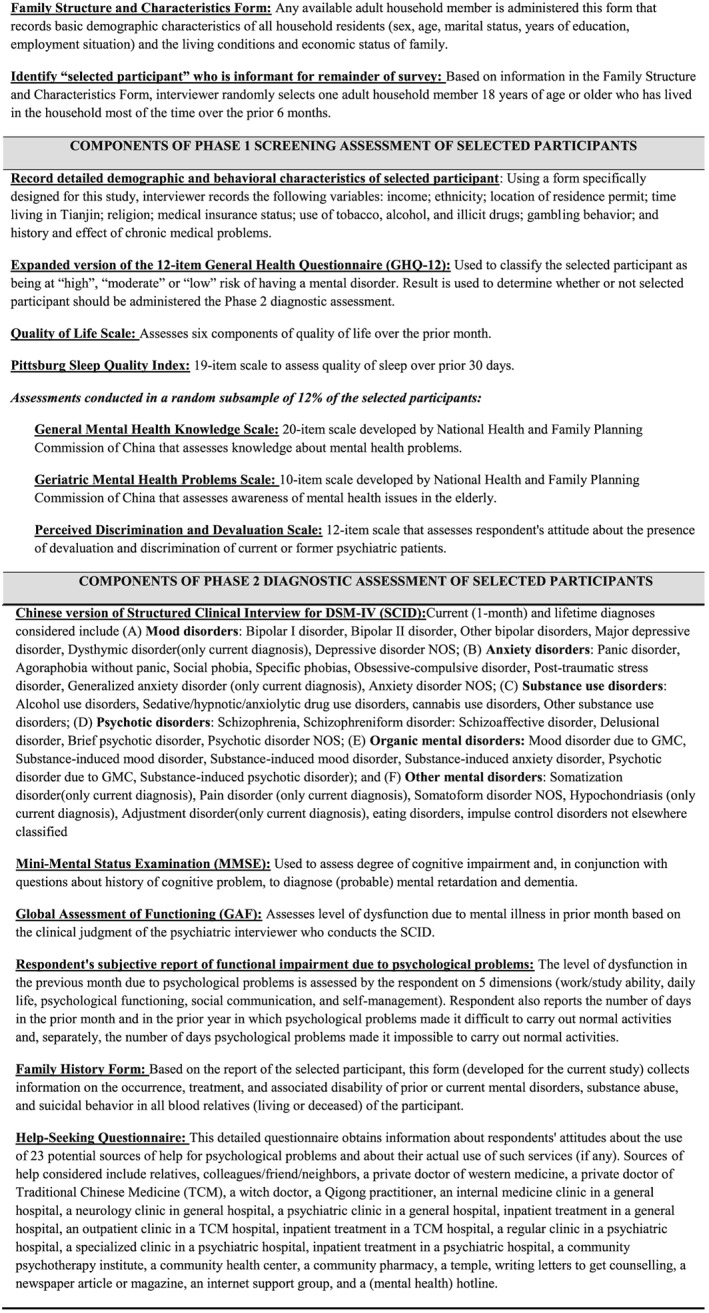

An overview of the assessments made in the Phase 1 screening assessment and the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment is shown in Figure 3. All instruments used in this survey were interviewer‐administered. Some of the instruments have been used as self‐completion scales in other studies, but we expected that a substantial minority of the sample would be illiterate or semi‐literate (24% of the final sample had had six or less years of formal education) who would, thus, either need to be excluded or read the instruments by the interviewer. To ensure that we could include the most representative sample possible and to avoid the methodological problem of combining data collected by different methods (i.e. self‐completion and interviewer‐completion), we standardized the data collection method by converting self‐completion instruments to interviewer‐completion instruments but having the interview read the items of these scales to respondents and recording their responses.

Figure 3.

Overview of the assessments made in the Phase 1 screening assessment and the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment

3.1. Family structure and characteristics form

This form is completed by the interviewer using information provided by any adult householder. All people living in the selected household for more than three of the last six months were ranked by age on the form and the following information was collected for each individual: sex, age, marital status, years of education, work status, whether or not a formal resident of Tianjin based on the “hukou” (an individual's official, government‐based household registration), days unable to work due to physical disease in the past year, and whether they had seen a doctor because of a psychological problem in their lifetime. Additional information about the living conditions and economic status of the household was also obtained.

3.1.1. Phase 1 screening assessments

3.1.1.1. Detailed demographic and behavioral characteristics of selected participant

After the selected participant is identified and provides written informed consent to participate in the survey, more detailed demographic and behavioral information about the participant (beyond that recorded in the Family Structure and Characteristics Form) is obtained by the interviewer. A brief form specifically developed for this survey was used to record the following variables: income; ethnicity; location of residence permit; time living in Tianjin; religion; medical insurance status; use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs; gambling behavior; and history and effect of chronic medical problems.

3.1.1.2. Expanded version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12)

The modified GHQ (Phillips et al., 2009b) consists of the original Chinese version of the GHQ‐12 (Yang, Huang, & Wu, 2003) (Cronbach's alpha coefficient = 0.75; test–retest reliability interclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.72) and nine additional items. This expanded version of the GHQ‐12 was used in the screening phase of the survey because the added items have been shown to increase the instrument's sensitivity for SCID diagnoses (Phillips et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2008). The nine additional items included the following: (1) respondents' subjective report of their physical health in the past month (rated as excellent, very good, good, fair, poor); (2) respondents' subjective report of their psychological health in the past month (rated as excellent, very good, good, fair, poor); (3) obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors in the last month (rated as never, seldom, sometimes, frequent); (4) restriction of activities because of phobias in the past month (rated as never, seldom, sometimes, frequent); (5) feelings of extreme nervousness or anxiety in the last six months (never, seldom, sometimes, frequent); (6) social problems due to drinking in the last year (never, seldom, sometimes, frequent); (7) any previous treatment for psychological problems (yes or no); (8) previous suicidal ideation or behavior (yes or no); (9) observed “significant psychiatric or cognitive problems” during the screening interview by the interviewing psychiatrist (yes or no). Responses of “poor”, “frequent” or “yes” were coded “1” (positive); all other responses were coded “0” (negative).

The original 12 GHQ‐items covered a range of health‐related questions and were scored as follows: 0 = “better than usual”, 0 = “as usual”, 1 = “less than usual” and 1 = “much less than usual”, so the total score ranged from 0 to 12. Respondents with a GHQ‐12 score of at least 4 or a positive score on any of the nine additional items were classified as “high‐risk” for mental disorder; those with a GHQ‐12 score of 1 to 3 and no endorsement of any of the nine additional items were classified as “moderate‐risk”, and those with no endorsement of any GHQ‐12 items or any of the nine additional items were classified as “low‐risk”. All high‐risk individuals, a 40% random selection of moderate‐risk individuals, and a 10% random sample of low‐risk individuals were subsequently selected for the Phase 2 diagnostic assessments.

3.1.1.3. Quality of life scale

This scale consists of six questions to assess how respondent rate their physical health, mental health, work status, economic status, relationship with family members, and relationships with other people in the past month. Each question is answered on a 5‐point scale (1 = “very poor”, 2 = “poor”, 3 = “fair”, 4 = “good” and 5 = “very good”). The scores are summed up and transformed to a 0–100 scale (total score = [(sum scores −5)/25] × 100), with higher scores indicating a higher quality‐of‐life. This simple‐to‐use scale was specifically developed for use in China; several studies employing the scale over the last decade report good psychometric properties and find that the results of the scale (i.e. the total quality of life score) help discriminate different groups of respondents (Bi et al., 2010; Conner, Phillips, & Meldrum, 2007; Li, Phillips, Zhang, Xu, & Yang, 2008; Phillips et al., 2002). In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha for the six items in the scale was 0.81 and the ICC for the test–retest reliability of the total score was 0.64.

3.1.1.4. Pittsburg sleep quality Index (PSQI)

The Chinese version of this 19‐item scale (Liu, 1999) is used to assess sleep quality over the prior 30 days. The scale assesses seven aspects of sleep and the total score has a theoretical range is 0 to 57. A total score > 7 is considered the cutoff for poor sleep quality. The results of using this scale in the current study are already published in Chinese (Yan, Xu, & Yin, 2015).

3.1.1.5. Subsample administered three additional scales

A random subsample of about 12% of the respondents who participated in the Phase 1 screening was administered three additional scales. These individuals were identified as follows: all selected households in each PSU were assigned a unique sequential study number (1001, 1002, 1003, etc.), so study numbers in which the last two digits of the 4‐digit number ranged from “xx00” to “xx11” accounted for approximately 12% of all study numbers; subjects who completed the Phase I screening who came from households with these study numbers were potential participants in this subsample.

General Mental Health Knowledge Scale: a 20‐item questionnaire developed by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China which includes 16 dichotomous response (“yes”/“no”) items that assess knowledge about basic mental health issues and four items that ask respondents whether or not they are aware of annual days related to mental health (e.g. world mental health day). The total score ranges from 0 to 20 with higher scores representing better mental health literacy. The translation of this scale and the scoring methods are shown in the Appendix. The results of using the scale in the current study have been published in Chinese (Huang, Xu, Yin, & Tian, 2015). The psychometric properties of this scale have not been assessed.

Geriatric Mental Health Problems Scale: a 10‐item dichotomous response scale (“yes”/“no”) questionnaire developed by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China was used to assess knowledge about geriatric mental health problems. The total score for the scale ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores representing greater awareness of geriatric mental health problems. The psychometric properties of this scale have not been assessed. The translation of this scale and scoring methods are shown in the Appendix (more information about the scale is available at: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn ).

Perceived Discrimination and Devaluation (PDD) Scale: Originally developed by Link and colleagues (Link, Mirotznik, & Cullen, 1991; Link, Struening, Neese‐Todd, Asmussen, & Phelan, 2001), this scale has six items that assess the presence of devaluation and discrimination experienced by current or former psychiatric patients and six items that assess the absence of devaluation and discrimination. The Chinese version of the PDD scale, which uses the same items as the original version but has a slightly different response set (adding the option “not sure”) was previously shown to have acceptable psychometric properties (Yin, Xu, Yang, & Tian, 2014). The results of using the scale in the current study have been published in Chinese (Xu, Yin, Yang, & Tian, 2014).

3.1.2. Phase 2 diagnostic assessments

3.1.2.1. Structured clinical interview for the diagnostic and statistical manual (SCID)

The Chinese version of the SCID (First et al., 2002; Phillips & Liu, 2011) includes all common diagnoses in the fourth edition of the DSM. It also includes the “not otherwise specified” (NOS) diagnostic categories of mental illnesses for individuals who have clinically significant symptoms combined with social dysfunction but do not meet full criteria for a specific disorder. The TJMHS was the first study to use the SCID module on impulse control disorders not elsewhere classified (First, 2008). Most diagnoses can be recorded as “lifetime” (i.e. met diagnostic criteria at any time in the individual's lifetime) or “current” (i.e. met diagnostic criteria at any time in the previous month). The full list of diagnoses considered is shown in Figure 3. Multiple comorbid diagnoses can be recorded; when more than one diagnosis is present, the examiner ranks them based on their clinical importance. The Chinese SCID has been shown to be reliable and valid (Phillips et al., 2009a).

3.1.2.2. Mini‐Mental state examination (MMSE)

The Chinese version of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Wang, Xiong, & Phillips, 1991) was incorporated into the Chinese version of SCID to assess cognitive impairment in respondents. MMSE results are combined with questions about the history of cognitive problems to determine the diagnoses of (probable) mental retardation and dementia. The theoretical total score for MMSE is 39; total scores below 24 in illiterate respondents, below 28 in respondents with a primary school education (i.e. five or six years of formal schooling), and below 32 in respondents who had completed middle school (i.e. eight or nine years of formal education) were considered indicative of cognitive impairment. The ICC for the test–retest reliability of the MMSE total score in this study was 0.91.

3.1.2.3. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, & Cohen, 1976) was used to assess the level of dysfunction in the previous month due to mental illness. This measure is defined in DSM‐IV and assessed by the diagnosing clinician as part of the SCID interview; the clinician uses clinical judgment to rate the most severe level of functional impairment caused by the psychiatric condition over the last month and on a 0–100 scale, with lower scores representing worse functioning. A disability weight was estimated using the GAF score (disability weight = (100 − GAF score)/100), and individuals with a disability weight of 0.40 or greater were defined as “moderately to severely disabled”.

3.1.2.4. Respondent's subjective report of functional impairment due to psychological problems

We also assessed respondents' subjective view about the extent to which the psychological symptoms they had experienced affected their functioning over the prior month. The areas of functioning considered included work or study, daily life, psychological functioning, social interactions, and self‐management. The degree of impairment over the prior month was rated as “none”, “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”, or “very severe”. Four other, more objective measures of impairment were obtained by asking respondents to indicate the number of days over the prior month and over the prior year in which psychological problems had hampered their ability to function or made it completely impossible to carry out their usual activities. The psychometric properties of these two measures have not, as yet, been assessed.

3.1.2.5. Family history form

If the respondent reported that any biological relative had experienced a mental illness, additional information was collected about the relative's relationship with the participant, the diagnosis (if available), the treatment history, and suicidal behavior.

3.1.2.6. Help‐seeking questionnaire

A detailed questionnaire to assess respondents' attitudes about help seeking for psychological problems and their actual help‐seeking behavior for psychological problems was included in the expanded Chinese version of the SCID (Phillips & Liu, 2011) and administered to all respondents (whether or not they had a SCID diagnosis). Twenty‐three potential sources of help for psychological problems are considered (listed in Figure 3). For each potential source of help, participants were asked if they had ever went to the provider for problems with emotions, nerves, mental health, or the use of alcohol or drugs (response scale: “yes”/“no”). Next, respondents who had used this type of provider were asked detailed questions about their experience including the number of times they had employed the service, the person(s) who recommend they use the service, the types of diagnoses and treatment recommendations (if any) they received, the travel time to use the service, the cost of the services, and their satisfaction with the result. Respondents who had not used a particular type of provider were asked if they thought this type of provider would be helpful for persons with mental health problems (response scale: “not effective”, “possibly effective”, and “certainly effective”).

4. FIELDWORK

4.1. Fieldwork staff and training

The fieldwork staff consisted of different teams of trained specialists.

Six “field supervisors” were experienced fieldwork interviewers. They trained the TJMHS staff and supervised sampling, data collection and recording, and interview quality.

The “household sampling team” consisted of six psychiatric nurses who were trained for seven days about the overall design and goals of the study, about the process of enumerating and selecting households at each PSU, and about the steps needed to prepare the sites for the survey. They were responsible for visiting every sampling site to contact local officials, for randomly selecting households, for identifying local guides, and for disseminating information about the survey prior to the arrival of the survey teams.

“Local guides” were local officials responsible for providing information about the sampling sites and helping the field workers enter selected households. They were instructed by the household sampling team about the purpose and the procedures of the survey.

The “within‐household sampling staff” consisted of six psychiatric nurses and six psychiatrists who were given five days of training about introducing the study to householders, recording all individuals living in selected households, and randomly selecting an eligible individual from the household. Their responsibility was to visit identified households, complete the first part of the household structure form (i.e. sex and age of all residents), and randomly select a household member as the target respondent for the main survey.

The “psychiatrist interviewers” included 44 psychiatrists with a minimum of three years of clinical experience from 18 mental health institutes in Tianjin. They participated in two training sessions: a 5‐day initial training session about the design of the project and the screening procedures, and a rigorous 15‐day training session in the administration of the household structure form and the screening and diagnostic instruments. After the training, they were tested to ensure they had mastered the required content; one participant was excluded because of his failure in the test.

Twelve of the 44 psychiatrists were selected as “SCID quality control evaluators”. The decision about which psychiatrists were best suited for this role was made by the study principle investigator at the end of the training based on their skill in administering the SCID and on their willingness and ability to identify and correct problems in the administration of the SCID by their fellow psychiatrists.

The “team managers” were 12 psychiatric nurses. They were trained for seven days in the overall goals and methods of the study with a focus on the responsibilities of different participants and the methods of ensuring quality control of the project. They were responsible for coordinating the interview fieldwork, monitoring the quality of the screening forms, recording the required information in the management forms, uploading voice recordings of the interviews, and assigning clinicians to complete the retesting evaluations.

Each of the six fieldwork teams included two within‐household sampling staff members, two team managers, one or two local guides, and seven to eight psychiatrist interviewers (two of whom were also responsible for SCID quality control).

4.2. Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted in two communities (n = 1,000) for 13 days to help the fieldworkers get acquainted with the procedures and to detect any potential problems. The pilot study found that having the same psychiatrist select the target respondent and administer the SCID resulted in a biased sample because psychiatrists almost always selected individuals who were currently available in the household. To ensure that the sample selection was based on all household members (whether or not they were in the household at the time of the Phase 1 screening), in the main study the target respondent was first randomly selected by the independent “within‐household sampling staff” (as described earlier in the “Sampling” section) and then the interviewer psychiatrist completed the remainder of the family structure form and the SCID.

4.3. Fieldwork procedures

An outline of the fieldwork procedures are shown in Figure 1. At least one week prior to the interviews at each PSU, the household sampling team contacted the local guides, who helped them enumerate all households at the sampling site and assign each household a unique sequential number (1, 2, 3, etc.). In many cases the housing lists available at local administrative offices had to be updated due to the construction of new buildings, the vacancy of housing units, or other types of changes. Each household in multiple‐household units (e.g. apartment buildings) was assigned a unique number. As described earlier in the Methods section, a simple random method was used to select the required number of households, and then each selected household was given a sequential study identification number (1001, 1002, 1003, etc.) and assigned to the interview team that would subsequently visit the site.

Three or four members of the interview team would visit each household assigned to their team. If no one was at home, they revisited the address on three different days at different times of the day to locate a family informant; if none were located after three visits, the household was classified as “unoccupied” or “residents not present”.

When an adult householder was available:

the local guide introduced the project and the team members;

the within‐household sampling staff person randomly selected one adult resident as a target subject using a random number table;

the psychiatrist interviewer completed the family structure form;

if the target subject was present and provided written informed consent for the interview, the psychiatrist interviewer conducted the Phase 1 screening interview immediately, if the subject was not available, an appointment for the interview was made;

if the Phase 1 screening interview was completed, the team manager determined (a) whether the three subsample forms should be completed (as described in the “Methods” section earlier, individuals for whom the last two digits of the study number ranged from “00” to “11” complete these forms); (b) whether an independent retest of the screening interview should be arranged (see “Quality control”, later), and (c) based on the results of the expanded GHQ‐12, whether a Phase 2 diagnostic assessment was required;

if the diagnostic SCID assessment was required, the psychiatrist interviewer either conducted it immediately after the screening interview or made an appointment to conduct it later;

if the SCID interview was completed, the team manager determined whether or not an independent retest of the SCID diagnostic assessment should be arranged (see “Quality control” section, later).

All interviews with selected participants were administered at the participants' homes in a separate room without disturbance from other people (if at all possible). If the subject had dementia, mental retardation, or a psychological disturbance that limited his/her participation in the interview, a caregiver who could provide detail information about the subject was asked to take part in the interview. The median (interquartile range) duration of the Phase 1 screening interview was 10 minutes (10–15 minutes) for individuals who did not complete the three supplementary scales and 15 minutes (12–20 minutes) for those who did complete the three supplementary scales. The median duration of the Phase 2 diagnostic interview was 35 minutes (30–40 minutes) for individuals without any lifetime diagnosis and 40 minutes (30–60 minutes) for individuals with any lifetime diagnosis.

All interviews were audio recorded for later quality control.

4.4. Quality control

We wanted to retest the Phase 1 screening instrument in a random sample of 5% of the screened respondents so we initially invited individuals in whom the last two digits of the sequential study number ranged from “20” to “26” (i.e. approximately 7% of all respondents) to participate in a re‐assessment. However, the refusal rate for repeating the Phase 1 screening part of the survey was over 50%, so to ensure that enough participants repeated the screening part of the survey, we subsequently expanded the selection to include individuals in whom the last two digits of the study number ranged from “20” through “39”. The team manager arranged for the repeat assessment by someone who was not involved in (and did not know the result of) the initial screening assessment within two to five days after the initial assessment.

Among individuals administered the SCID, all individuals with a current or past mental disorder and a random selection of 10% of those without a mental disorder were selected for retesting with the SCID. The team manager arranged for a psychiatrist who was blind to the initial interview to conduct the screening retest and/or diagnostic retest within two to five days after the initial evaluation. The team manager recorded all the information about each interview in a management form, and conducted quality control of the screening interview by ensuring that all items in the forms were filled out.

Two psychiatrists in each interview team were responsible for confirming the accuracy of diagnoses recorded on the SCID by checking the interview recording form. If a problem was identified, the quality‐control psychiatrist discussed the case with the interviewer and listened to the tape recording of the interview to correct the problem. In cases where a second SCID examination was conducted, quality‐control psychiatrists compared the diagnoses made in the first and retest interviews; if different, they listened to the recorded interviews, discussed the case with the two psychiatrists, and determined the final diagnosis.

Field supervisors monitored the interview quality throughout the study. In the first two weeks, a field supervisor accompanied each team, randomly monitoring the interview technique of each psychiatrist on the team. From the third week onward, a field supervisor joined each team for two days each week to monitor the administration of the surveys and answer team members' questions about the conduct of the interviews.

All non‐identified data collected in the survey were double‐entered and checked using Epidata 3.0. The data were then transferred to SPSS format and multiple cleaning steps were undertaken prior to conducting the analysis.

5. STATISTICAL METHODS

5.1. Post‐stratification weights

First, results from the diagnostic sample were weighted up to reflect the number of individuals in each research site. This was done for each risk‐stratum by multiplying the proportion of screened respondents in each stratum per neighborhood/village with the total number of individuals in the neighborhood/village and dividing this number by the number of SCID interviews in the stratum. These weights were truncated at 2 standard deviations above the mean weight to minimize the influence of extreme weights. Next, post‐stratification weights were created to make the weighted socio‐demographic distribution of the sample comparable in terms of location of residence (urban versus rural), gender, and age‐group (18–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–64 years, and 65+ years) to that of the 2010 Tianjin population reported in the Sixth National Population Census of China.

5.2. Statistical analyses

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to compare the association of target participants' age, sex, urban/rural residence, marital status, employment status, education, income, and household size with non‐completion of the Phase 1 screening and Phase 2 diagnostic assessments. Weighted test–retest kappa values were calculated for the three levels of risk of a mental illness (i.e. low, moderate, and high risk) and for different classes of current mental disorders (affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorders, psychotic disorders, and organic mental disorders). Design‐adjusted standard errors were estimated by Taylor series linearization to account for the unequal sampling across risk strata and possible homogeneity within sampling‐sites (clusters). Weighted and unweighted results were compared. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v23.0.

6. RESULTS

6.1. Response rates

Figure 2 illustrates the breakdown of the TJMHS sample. In total, 2,928 (18.8%) of the selected households were excluded, more than half of which were excluded because the household was unoccupied. A much higher proportion of the selected urban households were excluded than the selected rural households—21.6% (2,501/11,573) versus 10.7% (427/3,965). The family screening form was successfully completed and an adult householder was identified as the target respondent for 12,610 (81.2%) households. However, 862 (6.8%) of these identified respondents did not complete the screening interview. Thus 11,748 individuals completed the Phase 1 screening interview; slightly less than the estimated sample size required of 11,909. The test–retest assessment of the Phase 1 screening was completed in 46.6% (682/1,463) of individuals selected for retesting.

Based on screening with the expanded GHQ, 56.6% of respondents were classified as low‐risk of a mental disorder, 20.4% as moderate‐risk, and 23.0% as high‐risk. All high‐risk individuals, a 45.7% random sample of moderate‐risk individuals, and a 11.5% random sample of low‐risk individuals were selected for participation in the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment. Of the 4,563 selected individuals, 4,438 (97.3%) participated in the expanded SCID interview. The test–retest assessment of the SCID was completed in 44.9% of individuals selected for retesting.

6.2. Respondent characteristics

Table 1 compares the socio‐demographic characteristics of target respondents who did and did not complete the Phase 1 screening. Most of the characteristics assessed were significantly different between the two groups. In the univariate analysis, individuals who completed the screening were more likely to be female; living in urban areas; older; less well educated; married, divorced or widowed; to have above‐median per capita family incomes; to have fewer adult household members; and to be retired. After including all of these variables in the multivariate analysis, female gender, urban residence, above median income, and having fewer household members remained significantly associated with successful completion of the Phase 1 screening interview.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of individuals who did and did not complete Phase 1 screening for the Tianjin Mental Health Survey

| Characteristic | Phase 1 screening status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| completed (n = 11,748) % | not completed (n = 862) % | univariate analysis OR (95%CI)a | multivariate analysisb OR(95%CI)a | |

| Sex | ||||

| male | 44.6% | 56.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| female | 55.4% | 43.2% | 1.64 (1.42–1.88) | 1.39 (1.20–1.62) |

| Residence | ||||

| rural | 27.7% | 33.1% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| urban | 72.3% | 66.9% | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | 1.25 (1.03–1.51) |

| Age range | ||||

| 18–29 | 12.9% | 20.2% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–39 | 16.4% | 24.7% | 1.04 (0.84–1.28) | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) |

| 40–49 | 20.3% | 24.9% | 1.27 (1.03–1.56) | 1.14 (0.87–1.50) |

| 50–64 | 31.8% | 20.3% | 2.45 (1.97–3.04) | 1.49 (1.11–2.00) |

| 65+ | 18.6% | 9.9% | 2.94 (2.25–3.85) | 1.32 (0.89–1.95) |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–6 | 23.8% | 18.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 7–9 | 33.0% | 31.8% | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) |

| 10–12 | 23.2% | 26.0% | 0.70 (0.57–0.87) | 1.04 (0.81–1.34) |

| 13+ | 20.0% | 23.4% | 0.67 (0.54–0.83) | 1.15 (0.86–1.52) |

| Per capita family income | ||||

| below median | 47.3% | 38.1% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| above median | 51.1% | 56.6% | 1.38 (1.91–1.59) | 1.28 (1.09–1.54) |

| Unknown | 1.6% | 5.3% | 0.33 (0.24–0.46) | 0.37 (0.26–0.53) |

| Marital status | ||||

| never married | 8.2% | 13.1% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| married/co‐habiting | 80.3% | 79.5% | 1.61 (1.31–1.99) | 1.18 (0.88–1.58) |

| divorced/widowed | 11.5% | 7.4% | 2.46 (1.79–3.39) | 0.83 (0.55–1.26) |

| Number of adults in household | ||||

| 1 | 11.6% | 5.5% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 55.8% | 48.6% | 0.54 (0.40–0.73) | 0.55 (0.39–0.79) |

| 3 | 21.1% | 28.7% | 0.34 (0.25–0.47) | 0.40 (0.28–0.58) |

| 4 or above | 11.5% | 17.3% | 0.31 (0.22–0.44) | 0.33 (0.23–0.49) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Housewife | 9.0% | 5.5% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Farmer | 11.5% | 66.8% | 0.88 (0.60–1.29) | 1.03 (0.69–1.54) |

| other employed | 41.9% | 11.1% | 0.38 (0.28–0.51) | 0.39 (0.28–0.54) |

| unemployed | 9.3% | 8.7% | 0.64 (0.44–0.93) | 0.64 (0.44–0.94) |

| Retired | 28.3% | 7.9% | 1.53 (1.08–2.19) | 1.04 (0.81–1.55) |

Confidence intervals in bold type are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

The multivariate logistic regression includes all the variables in the table.

Table 2 shows compares the characteristics of individuals selected for the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment who did and did not complete the interview. There were few significant differences between the groups. In the univariate analysis, the oldest age group (65 or older) was significantly more likely to complete the interview than the youngest age group (18–29 years of age), and individuals currently employed in non‐agricultural jobs were significantly less likely to complete the interview than individuals whose employment status was classified as “housewife”. In the multivariate analysis, employment in non‐agricultural jobs and being 40–49 years old were significantly associated with completion of the diagnostic assessment.

Table 2.

Comparison of the characteristics of individuals selected for the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment for the Tianjin Mental Health Survey who did and did not complete the assessment

| Characteristic | Phase 2 assessment status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| completed (n = 4,438) % | not completed (n = 125) % | univariate analysis OR (95%CI)a | multivariate analysisb OR (95%CI)a | |

| Sex | ||||

| male | 42.5% | 44.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| female | 57.5% | 55.2% | 1.10 (0.77–1.57) | 0.96(0.66–1.41) |

| Residence | ||||

| rural | 24.8% | 27.0% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| urban | 75.2% | 73.0% | 0.89 (0.59–1.34) | 0.76(0.45–1.28) |

| Age range | ||||

| 18–29 | 9.8% | 15.2% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30–39 | 14.3% | 15.2% | 1.47(0.77–2.80) | 1.87(0.92–3.8) |

| 40–49 | 19.8% | 17.6% | 1.74(0.94–3.26) | 2.23(1.09–4.55) |

| 50–64 | 33.1% | 36.0% | 1.43(0.83–2.47) | 1.48(0.73–3.02) |

| 65+ | 23.1% | 16.0% | 2.24(1.18–4.24) | 2.11(0.86–5.19) |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–6 | 28.4% | 28.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 7–9 | 33.0% | 33.6% | 1.00(0.64–1.57) | 1.34(0.80–2.24) |

| 10–12 | 22.2% | 20.0% | 1.13(0.67–1.89) | 1.66(0.91–3.02) |

| 13+ | 16.3% | 17.6% | 0.94(0.54–1.61) | 1.55(0.78–3.09) |

| Per capita family income | ||||

| below median | 45.2% | 40.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| above median | 53.0% | 57.6% | 1.20(0.84–1.73) | 1.38(0.91–2.11) |

| unknown | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.22(0.30–5.08) | 1.24(0.3–5.18) |

| Marital status | ||||

| never married | 6.5% | 7.2% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| married/co‐habiting | 77.8% | 80.0% | 1.07(0.54–2.14) | 0.59(0.26–1.39) |

| divorced/widowed | 15.7% | 12.8% | 1.35(0.59–3.09) | 0.92(0.33–2.53) |

| Number of adults in household (age ≥ 18) | ||||

| 1 | 13.9% | 15.2% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 54.3% | 52.8% | 1.12(0.67–1.88) | 1.7(0.86–3.34) |

| 3 | 20.3% | 23.2% | 0.95(0.53–1.71) | 1.4(0.69–2.83) |

| 4 or above | 11.4% | 8.8% | 1.42(0.67–3.01) | 2.15(0.9–5.18) |

| Employment status | ||||

| housewife | 9.2% | 4.8% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| farmer | 11.9% | 9.6% | 0.65 (0.24–1.74) | 0.59(0.21–1.66) |

| other employed | 35.3% | 48.0% | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | 0.32(0.13–0.78) |

| unemployed | 11.6% | 12.8% | 0.48 (0.18–1.22) | 0.46(0.18–1.21) |

| retired | 32.0% | 24.8% | 0.68 (0.28–1.63) | 0.60 (0.23–1.53) |

Confidence intervals in bold type as statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

The multivariate logistic regression includes all the variables in the table.

6.3. Test–retest reliability

Overall, 682 respondents were retested with GHQ and 1089 were retested with SCID. The weighted test–retest kappa value for the three levels of risk of a mental illness was 0.60. The test–retest kappa values for a current diagnosis (yes/no) based on the SCID assessments were 0.76 for affective disorders, 0.82 for anxiety disorders, 0.80 for substance abuse disorders, 0.93 for psychotic disorders, and 0.64 for organic mental disorders.

6.4. Characteristics of weighted samples

Table 3 shows the distribution of demographic variables in the study sample before and after weighting. Both the Phase 1 sample and the Phase 2 sample were weighted to have the same gender‐by‐age‐by‐residence (urban versus rural) distribution as that of persons 18 years of age or older in Tianjin reported in the 2010 census: 46.6% females, 81.0% living in urban communities, and a weighted mean (standard deviation) age of 42.1 (16.2) years. The crude mean years of education in the Phase 1 sample was 9.6 (4.4) years and the weighted mean years of education was 10.8 (4.0) years. The weighted median (interquartile range) per capita family monthly income in the Phase 1 sample was ¥1,333 (¥950–¥2,000) (excluding data for 186 individuals who refused to report family income).

Table 3.

Sample characteristics before and after weighting

| Characteristic | Phase 1 screening assessment | Phase 2 diagnostic assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Unweighted % | weighted % | n | unweighted % | weighted % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| male | 5,238 | 44.6% | 53.4% | 1,884 | 42.5% | 53.4% | |

| female | 6,510 | 55.4% | 46.6% | 2,554 | 57.5% | 46.6% | |

| Residence | |||||||

| Rural | 3,253 | 27.7% | 19.0% | 1,199 | 27.0% | 19.0% | |

| Urban | 8,495 | 72.3% | 81.0% | 3,239 | 73.0% | 81.0% | |

| Age range | |||||||

| 18–29 | 1,519 | 12.9% | 30.6% | 434 | 9.8% | 30.6% | |

| 30–39 | 1,932 | 16.4% | 18.4% | 636 | 14.3% | 18.4% | |

| 40–49 | 2,379 | 20.3% | 19.2% | 878 | 19.8% | 19.2% | |

| 50–64 | 3,734 | 31.8% | 22.1% | 1,467 | 33.1% | 22.1% | |

| 65+ | 2,184 | 18.6% | 9.8% | 1,023 | 23.1% | 9.8% | |

| Years of education | |||||||

| 0–6 | 2,796 | 23.8% | 15.1% | 1,261 | 28.4% | 15.3% | |

| 7–9 | 3,874 | 33.0% | 29.4% | 1,466 | 33.0% | 31.9% | |

| 10–12 | 2,725 | 23.2% | 26.3% | 987 | 22.2% | 26.8% | |

| 13+ | 2,348 | 20.0% | 29.2% | 724 | 16.3% | 26.1% | |

| Pre capital family income | |||||||

| below median | 6,005 | 51.1% | 50.8% | 2,354 | 53.1% | 48.8% | |

| above median | 5,557 | 47.3% | 47.5% | 2,004 | 45.2% | 49.7% | |

| unknown | 186 | 1.6% | 1.6% | 80 | 1.8% | 1.5% | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| never married | 966 | 8.2% | 17.9% | 290 | 6.5% | 15.5% | |

| married/co‐habiting | 9,433 | 80.3% | 76.7% | 3,451 | 77.8% | 78.3% | |

| divorced/widowed | 1,348 | 11.5% | 5.4% | 697 | 15.7% | 6.1% | |

| Number of adults in household (age ≥ 18) | |||||||

| 1 | 1,367 | 11.6% | 4.3% | 619 | 13.9% | 5.3% | |

| 2 | 6.559 | 55.8% | 47.5% | 2,411 | 54.3% | 52.7% | |

| 3 | 2,473 | 21.1% | 30.1% | 900 | 20.3% | 25.6% | |

| 4 or above | 1,349 | 11.5% | 18.0% | 508 | 11.4% | 16.4% | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| housewife | 1,061 | 9.0% | 10.1% | 407 | 9.2% | 9.2% | |

| farmer | 1,351 | 11.5% | 8.4% | 528 | 11.9% | 8.1% | |

| other employed | 4,923 | 41.9% | 54.8% | 1,568 | 35.3% | 54.2% | |

| unemployed | 1,088 | 9.3% | 9.4% | 515 | 11.6% | 11.0% | |

| retired | 3,325 | 28.3% | 17.3% | 1,420 | 32.0% | 17.5% | |

7. DISCUSSION

The TJMHS is the first large‐scale representative survey of mental disorders in Tianjin, one of Chinas most rapidly developing mega‐cities. The results will be relevant for several other highly urbanized areas of China (and, possibly, urban areas of other low‐ and middle‐income countries) that have experienced rapid growth, economic development, and an influx of rural migrants. The survey provides detailed epidemiological, attitudinal, and care‐seeking data about mental health disorders that is essential to the development and assessment of targeted mental health policies and programs. Moreover, the methods and results of this survey can serve as a baseline for future research aimed at monitoring the implementation of China's new national mental health law (Chen et al., 2012) and of the recent national Mental Health Plan for 2015 to 2020 (Xiong & Phillips, 2016).

The survey used a two‐phase design to enable the use of a rigorous clinical diagnostic interview (SCID) on an enriched sample of individuals at high, moderate, and low risk of mental disorders. This method makes it possible to maximally use available psychiatric manpower (which is very limited in most low‐ and middle‐income countries) to arrive at reasonably precise estimates of the prevalence of relatively uncommon conditions (such as schizophrenia). We provide exhaustive details about the study procedures and methods so other investigators can adapt the study design and procedures for their own setting. Rigorous training, sampling, and quality control methods were adopted to optimize the quality of the results generated by the TJMHS. Other steps were taken to maximize participation and increase the likelihood that respondents would trust personal information with interviewers: engaging and training community‐based guides, local dissemination of information about the survey prior to conducting the survey, training interviewers to establish rapport with respondents, and having a single interviewer conduct both the Phase 1 screening and the Phase 2 diagnostic assessments.

The Phase 1 screening survey was completed in 11,748 individuals identified from the 15,538 households selected in Tianjin's 15 urban districts and three rural counties—a crude response rate of 75.6%. However, 900 of the selected households were permanently unoccupied (a common problem in both urban and rural China), so the adjusted response rate of 80.3% (11,748/14,638) is probably a more meaningful estimate. Among the 4,563 individuals selected to complete the Phase 2 diagnostic interview, 4,438 (97.3%) were successfully interviewed. These response rates are higher than those reported for most countries that participated in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys (WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004): France (45.9%), Belgium (50.6%), the Netherlands (56.4%), Japan(56.4%), Germany (57.8%), Lebanon (70.0%), United States (70.9%), Italy (71.3%), Mexico (76.6%), Nigeria (79.9%), Spain (78.6%), Ukraine (78.3%), and Colombia (87.7%).

We attribute the good response rate to the screening interview in our study to the involvement of “local guides” who were largely local officials well‐known by community residents. The very high response rate among individuals selected for the follow‐up Phase 2 diagnostic interview is probably related to the good rapport the interviewer established with the respondent while conducting the screening interview. However, this good rapport did not help when respondents were asked to repeat the screening interview for the test–retest assessment (47% completion rate) or when they were asked to repeat the diagnostic interview for the test–retest assessment (45% completion rate).

Several limitations of the survey need to be acknowledged. (1) TJMHS results will not be generalizable to the whole of China because of enormous regional differences. (2) All data about lifetime mental health conditions were collected retrospectively, which—as in all such studies—is affected by recall bias (Wells & Horwood, 2004; Moffitt et al., 2010). (3) As reported in earlier surveys (Kessler & Üstün, 2004; de Graaf, Ten Have, & van Dorsselaer, 2010), non‐participation in the screening interview for this survey was related to socio‐demographic variables, so it is possible that the prevalence of mental disorders also differs between those who did and did not participate. One prior analysis of non‐respondents in the Netherlands (Bijl, van Zessen, Ravelli, de Rijk, & Langendoen, 1998) suggests that non‐respondents have higher rates of mental illness while another study from the United States (Kessler et al., 2004) found no difference in the prevalence of mental disorders between respondents and non‐respondents. To minimize the effect of these differences, we use post‐stratification weights to make the sample of individuals who completed the Phase 1 screening and the Phase 2 diagnostic assessments comparable to the target population in terms of gender, age, and urban versus rural location of residence. (4) The psychometric properties of some of the scales employed in the study have not yet been formally assessed (e.g. the forms we developed for the study to collect demographic information, the two scales about mental health literacy developed by the National Health and Family Planning Commission, and the Health‐Seeking Questionnaire). (5) Less than half of the individuals selected to participate in retesting with the Phase 1 screening assessment and the Phase 2 diagnostic assessment completed the retesting and the time interval between the first and second evaluations was very short (two to five days) (due to the limited time the survey teams could spend at each PSU), so the assessment of the test–retest reliability of the measures may be biased.

Despite these limitations, the methodological improvements and more extended scope of the TJMHS compared to earlier psychiatric epidemiological studies in China make the TJMHS dataset a valuable addition to the literature. The study provides valuable new insights about the mental health status and the use of mental health services in Tianjin that is relevant for other rapidly developing urban regions in China. The TJMHS is a model for conducting ongoing studies of mental health conditions in rapidly changing urban communities both in China and in other low‐ and middle‐income countries.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

GX and MRP designed the study. HY and MRP analyzed the data. GX, MRP, HY, RAS, and KJW contributed to the interpretation of data. HY and KJW wrote the initial draft of the paper. All authors critically reviewed the draft and helped revise the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Tianjin Public Health Bureau, the clinicians who participated in the fieldwork, and the local guides for assistance with the fieldwork. The authors also thank Zhiqing Wang and Yeqing Xu for their contributions to the interviewer training and field supervision.

The Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS) was supported by funds from the Tianjin Finance Bureau and Tianjin Key Programs for Science and Technology Development in Health Industry (No. 13KG119).

APPENDIX A.

A.1.

| Translated version of two questionnaires developed by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China about (A) basic knowledge about mental health problems and (B) about mental health problems in the elderlya | ||

|---|---|---|

| A. DO YOU AGREE WITH THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS ABOUT MENTAL OR PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS? | ||

| 1. Mental health is an integral part of health. | yes | no |

| 2. Mental illnesses result from something wrong in thought. | yes | no |

| 3. Most people may have a mental problem, but they may not notice the problem. | yes | no |

| 4. Mental illnesses are all caused by stresses | yes | no |

| 5. Mental health includes normal intelligence, stable mood, harmonious relationships, and Good ability to adapt and so on. | yes | no |

| 6. Most mental illnesses cannot be cured. | yes | no |

| 7. If you suspect that you have mental problems or mental illnesses, you should go to a psychiatrist or psychologist for help | yes | no |

| 8. Individuals in any age can have a mental problem. | yes | no |

| 9. Mental illnesses or psychological problems cannot be prevented. | yes | no |

| 10. Even though a person is diagnosed with a severe mental disorder, he/she should take medication for only a short period rather than long‐term continuous. | yes | no |

| 11. Optimistic attitude towards life, good interpersonal relationship and healthy lifestyle are helpful for us to keep good mental health. | yes | no |

| 12. It is more possible for a person with a family history of mental disorders to develop mental disorders or mental problems. | yes | no |

| 13. The mental problems in adolescent do not influence their academic achievement. | yes | no |

| 14. It is less likely to have mental problems or disorders in middle‐age or older adults. | yes | no |

| 15. Someone with bad characters is more prone to have mental problems. | yes | no |

| 16. High psychological stress or major life events could induce mental problems or disorders. | yes | no |

| 17. Do you know/ have you heard the World Mental Health Day? | yes | no |

| 18. Do you know/ have you heard the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking? | yes | no |

| 19. Do you know/ have you heard the World Suicide Prevention Day? | yes | no |

| 20. Do you know/ have you heard the World Sleep Day? | yes | no |

| B. DO YOU AGREE WITH THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS ABOUT THE MENTAL PROBLEMS IN OLDER ADULTS? | ||

| 1. Memory loss is the manifestation at the beginning of dementia. | yes | no |

| 2. A good attitude, often participation in social activities may help older people to maintain mental health. | yes | no |

| 3. Mild dementia can be cured. | yes | no |

| 4. The most common reason of dementia is Cerebrovascular accident (stroke). | yes | no |

| 5. Depression is the most common mental disorder in older adults. | yes | no |

| 6. To exercise one's wits can often prevent dementia. | yes | no |

| 7. If older adults feel upset or restless, it may be the demonstrations of depression. | yes | no |

| 8. Paying too much attention to their physical health or having a suspicion of a physical disease without any evidence may be the manifestations of mental problem in older adults. | yes | no |

| 9. Individuals with geriatric depression may have a variety of somatic discomfort. | yes | no |

| 10. The main cause of geriatric depression is physical disease. | yes | no |

Scoring: for questionnaire (A) 1 point is given for each “yes” on items 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15–20,and 1 point is given for each “no” on items 2, 4, 6, 9, 10, 13 and 14; for questionnaire (B) one point is given for each” yes” response to items 1,2,3,5–9, and one point is given for each “no” response to items 4 and 10.

Yin H, Phillips MR, Wardenaar KJ, et al. The Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS): study rationale, design and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1535 10.1002/mpr.1535

REFERENCES

- Bi, B. , Tong, J. H. , Liu, L. , Wei, S. W. , Li, H. Y. , Hou, J. L. , … Phillips, M. R. (2010). Comparison of patients with and without mental disorders treated for suicide attempts in the emergency departments of four general hospitals in Shenyang, China. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32, 549–555, doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl, R. V. , van Zessen, G. , Ravelli, A. , de Rijk, C. , & Langendoen, Y. (1998). The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS): Objectives and design. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33, 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. H. , Phillips, M. R. , Cheng, H. , Chen, Q. Q. , Chen, X. D. , Fralick, D. , … Bueber, M. (2012). Mental health law of the People's Republic of China (English translation with annotations). Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 24(6), 305–321, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, K. R. , Phillips, M. R. , & Meldrum, S. (2007). Predictors of low‐intent and high‐intent suicide attempts in rural China. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1842–1846. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf, R. , Ten Have, M. , & van Dorsselaer, S. (2010). The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study‐2 (NEMESIS‐2): Design and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19, 125–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, C. , & Zhang, Q. (2014). Mental health services personnel and service categories in Tianjin. Continuing Mental Education, 28, 107–109 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Du, C. , Cui, B. , Wang, Y. , Chen, Z. , Zhang, B. , Sun, X. , … Tian, H. (2010). Survey of psychiatric hospitalization service in Tianjin in 2006. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 22, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott, J. , Spitzer, R. L. , Fleiss, J. L. , & Cohen, J. (1976). The Global Assessment Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33, 766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B. (2008). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR Impulse Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified (SCID‐ICD) (June 2008 draft). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B. , Spitzer, R. L. , Gibbon, M. , & Williams, J. B. (2002). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka, B. H. (2012). Depression as a disease of modernity: Explanations for increasing prevalence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140, 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Xu, G. , Yin, H. , & Tian, H. (2015). The awareness of mental health and its associates: a cross‐sectional survey in Tianjin community inhabitants. Journal of International Psychiatry, 42(4), 23–26 .in Chinese [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , & Üstün, B. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 93–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Berglund, P. , Chiu, W. T. , Demler, O. , Heeringa, S. , Hiripi, E. , … Zheng, H. (2004). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS‐R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 69–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Tsang, A. , Zhang, M.‐Y. , Huang, Y.‐Q. , He, Y.‐L. , Liu, Z.‐R. , … Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and inter‐cohort variation in DSM‐IV disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine, 37, 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. , Ze, C. , Cui, L. , Jiang, Q. , Shi, G. , Wu, H. , … Enyi, Z. (2008). Epidemiological survey of mental disorders in the people aged 18 and older in Hebei Province. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 1, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Y. , Phillips, M. R. , Zhang, Y. P. , Xu, D. , & Yang, G. H. (2008). Risk factors for suicide in China's youth: a case–control study. Psychological Medicine, 38, 397–406. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Wang, Z. , & Phillips, M. R. (2010). The methodology of pyschiatric epidemiological survey in community in China. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 24, 191–194 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G. , Mirotznik, J. , & Cullen, F. T. (1991). The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32, 302–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G. , Struening, E. L. , Neese‐Todd, S. , Asmussen, S. , & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self‐esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 52, 1621–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. C. (1999). Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 1999(Suppl), 31–35 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, T. E. , Caspi, A. , Taylor, A. , Kokaua, J. , Milne, B. J. , Polanczyk, G. , & Poulton, R. (2010). How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine, 40, 899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. (2004). Mental health in China: The challenges and chioces in 21st century. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. , & Liu, X. H. (2011). In First M. B., Spitzer R. L., Gibbon M., & Williams J. B. W. (Eds.), Translated and adapted Chinese version of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID‐I/P)). Shanghai: in ChineseSuicide Research and Prevention Center, Shanghai Mental Health Center. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. , Liu, H. , & Zhang, Y. (1999). Suicide and social change in China. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 23, 25–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. , Yang, G. H. , Zhang, Y. P. , Wang, L. J. , Ji, H. Y. , & Zhao, M. G. (2002). Risk factor for suicide in China: A national case–control psychological autopsy study. Lancet, 360, 1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. , Zhang, J. , Shi, Q. , Song, Z. , Ding, Z. , & Pang, S. (2009a). Mental illness in China – authors' reply. Lancet, 374, 1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R. , Zhang, J. , Shi, Q. , Song, Z. , Ding, Z. , Pang, S. , … Wang, Z. (2009b). Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: An epidemiological survey. Lancet, 373, 2041–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. , Zhang, M. , Huang, Y. , He, Y. , Liu, Z. , Cheng, H. , … Kessler, R. C. (2006). Twelve‐month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine, 36, 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tianjin Municipal Statistics Bureau and NBS Survey Office in Tianjin (2011). Tianjin Statistic Yearbook 2011. Beijing: China Statistics Press (in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Twelve‐Region Psychiatric Epidemiological Study Work Group (1986). The national 12‐region psychiatric epidemiological study – methodology and data analysis. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 19, 65–69 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. , Xiong, W. , & Phillips, M. R. (1991). Clinical test of Mini‐Mental State Examination in 400 schizophrenia. Zhongguo Minzheng Yixue Zazhi, 3, 145–148 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Ma, H. , & Zhao, Y. (2014). Exploring the relationship between urbanization and the eco‐environment—a case study of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Ecological Indicators, 45, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J. E. , & Horwood, L. J. (2004). How accurate is recall of key symptoms of depression? A comparison of recall and longitudinal reports. Psychological Medicine, 34, 1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey Consortium (2004). Prevalence, severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA, 291, 2581–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y. T. , Yu, X. , Sartorius, N. , Ungvari, G. S. , & Chiu, H. F. K. (2012). Mental health in China: Challenges and progress. Lancet, 380, 1715–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, W. , & Phillips, M. R. trans(2016). Translated and annotated version of the 2015–2020 National Mental Health Work Plan of the People's Republic of China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 28(1), 4–17. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G. M. , Yin, H. F. , Yang, G. F. , & Tian, H. J. (2014). Survey of mental illness stigma in community population in Tianjin City. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 28, 97–103 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G. , Xu, G. M. , & Yin, H. F. (2015). Epidemiological study on sleep quality of community population age 18 years or over in Tianjin. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 29(3), 199–203 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. , Huang, L. , & Wu, Z. (2003). Study on the appropriateness of the Chinese version of the General Health Questionnaire as a screening instrument for psychological disorders in mainland China. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 24, 769–773 (in Chinese).14521766 [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H. , Xu, G. , Yang, G. , & Tian, H. (2014). Reliability and validity of the Chinese‐version of the perceived devaluation‐discrimination scale in community population. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 28, 63–69 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. H. , & Song, S. (2003). Rural–urban migration and urbanization in China: Evidence from time‐series and cross‐section analyses. China Economic Review, 14, 386–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Shen, Y. , Li, S. , Chen, C. , Huang, Y. , Wang, J. , … Meng, G. (1998). Epidemiological investigation on neurosis in 7 areas of China. Chinese Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 80 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Cui, J. , Li, K. , Jiang, Q. , Xiuli, S. , Gao, L. , … Yang, B. (2008). Expanded edition of the General Health Questionnaire(GHQ‐12) in Epidemiogical Survey of Mental Illness. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 22, 189–192 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]