Abstract

The availability of appropriate stimulus material is a key concern for an experimental approach to research on alcohol use disorders (AUDs). A large number of such stimuli are necessary to evoke relevant alcohol‐related associations. We report the development of a large stimulus database consisting of 457 pictures of alcoholic beverages and 398 pictures of neutral objects. These stimuli were rated by 18 inpatients hospitalized due to severe AUD and 18 healthy controls along four dimensions: arousal, valence, alcohol‐relatedness, and craving. Physical parameters of the pictures were assessed.

After outlier removal, 831 stimuli that were characterized as either alcohol‐related or neutral were retained in the final stimulus pool. Alcohol‐related pictures (versus neutral pictures) evoked higher arousal, more craving and were judged to have higher alcohol‐relatedness and a more negative valence. Group comparisons indicated that in patients, neutral pictures evoked more craving and had higher alcohol‐relatedness than they did in controls. Physical parameters such as visual complexity, luminance, and color were extracted from these pictures, and extreme values were normalized to minimize mean differences between alcoholic and neutral stimuli. The pictures met the qualitative requirements for (neurophysiological) research. A data file containing rating values and physical parameters will be provided upon request.

Keywords: Alcohol, alcohol use disorders, craving, physical parameters, stimulus material

1. INTRODUCTION

To advance insight into the processes important for the development, maintenance, and therapy of alcohol use disorders (AUDs), scientists often adopt an experimental approach. While external and ecological validity in experimental studies are limited by nature, the use of appropriate stimulus material can ensure that this limitation is kept to a minimum. Appropriate stimuli thus activate the processes under investigation in a manner as naturalistic as possible and allow for the control of extraneous variables that are not of interest, thus improving internal validity. Experimental research on AUD requires adequate stimulus material to mimic alcohol‐related cues that patients may encounter in real‐life situations. It has been shown that alcohol‐related stimuli activate addiction‐related processes and provoke a variety of behavioral (Wiers et al., 2007), cognitive (Miller & Fillmore, 2010), physiological (Buckman, White, & Bates, 2010; Eddie et al., 2013), and neurophysiological (Dickter, Forestell, Hammett, & Young, 2013; Grüsser et al., 2004; Heinz et al., 2007; Myrick et al., 2008; Vollstädt‐Klein et al., 2011; Wrase et al., 2007) responses. These responses differ between patients and healthy controls and are potentially crucial for the development and maintenance of AUD. Generally, alcohol‐related pictures are among the most commonly used stimuli in AUD research. Pictorial stimuli have been argued to have higher ecological validity than words (Kreusch, Vilenne, & Quertemont, 2013). At the same time, they are easier to establish, to implement in experimental paradigms, and to control than other stimuli, such as videotaped scenes of drug use (Garavan et al., 2000) or olfactory cues (Grüsser, Heinz, & Flor, 2000).

However, not all (pictorial) stimuli that have been used in AUD research so far have met the requirements for stringent experimental investigations in clinical settings. To be of value in experiments devoted to clinical alcohol research, stimuli have to be clinically valid. At the same time, these stimuli have to be standardized and controlled for confounding factors. First, they should efficiently represent real‐life cues and be validated not only in healthy individuals but also in clinical AUD populations. Second, the stimuli need to be standardized with regard to their objective and subjective characteristics. Objective stimulus characteristics include physical stimulus parameters (e.g. hue, luminance, and visual complexity), while subjective stimulus characteristics include those describing the subjective appraisal of the picture content (e.g. valence, arousal, and alcohol‐relatedness). Both sets of characteristics should be considered during the standardization and validation processes to eliminate potential confounding factors and to increase explanatory power (Grüsser et al., 2000; Pulido, Brown, Cummins, Paulus, &Tapert, 2010; Wrase et al., 2002). Third, stimuli databases for experimental AUD research need to be sufficiently large in order to avoid stimulus repetition effects during experimental procedures. This is particularly a concern for neurophysiological studies (Luck, 2014; Myrick et al., 2008; Tapert et al., 2003). It is well established that electroencephalographic event‐related potentials (e.g. Olofsson & Polich, 2007) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) responses (e.g. Schwartz et al., 2003) are modulated and potentially confounded by stimulus repetition. Moreover, a large database of different stimuli devoted to alcohol research would allow for the extraction of individualized picture sets adapted to each individual participant. Individualized cues can enhance the salience of alcohol‐related cues (Lukas et al., 2013) and provide a more reliable estimation of cue‐related processes in AUD patients (Kreusch et al., 2013).

Borrowing from the definition of test validity by Borsboom, Mellenbergh, and Van Heerden (2004), and translating these considerations to the concept of stimulus validity (Pronk, van Deursen, Beraha, Larsen, & Wiers, 2015), stimuli would be considered as valid “if variations in the stimuli causally produce variations in the attribute” under investigation (Pronk et al., 2015, p. 2048). For instance, since we want the stimuli to activate addiction‐related concepts (such as memory contents) and provoke addiction‐related responses (e.g. craving), their systematic variations (i.e. their alcohol‐related content) should produce variations in their perceived alcohol‐relatedness and in the experienced craving. We consider the presented stimuli as valid if alcohol‐related and non‐alcohol‐related (neutral) stimuli consistently produce differences in perceived alcohol‐relatedness and the craving response. In contrast to Pronk et al. (2015), differences between subject groups are not imperative to establishing stimulus validity. In this view, stimulus validity stems from the stimulus characteristics exerting main effects on the attributes of concern (craving and alcohol‐relatedness), rather than from subject characteristics.

In the absence of an appropriate database of validated stimulus material, research has often drawn upon a variety of less‐validated resources, such as pictures from advertisements or Internet databases (Kreusch et al., 2013; Tapert et al., 2003). Such stimuli are insufficiently validated and are not adequately controlled with regard to their objective and subjective characteristics. Some research groups have undertaken the effort to develop standardized alcohol‐related stimuli for use in experimental tasks. For instance, Wrase et al. (2002) have developed alcohol‐associated cues to assess neuronal cue‐reactivity. Patients with AUDs and control subjects rated the alcohol‐relatedness, arousal, and valence of 32 alcohol‐related pictures, 18 pictures of non‐alcoholic beverages, and 10 neutral stimuli. The groups did not differ in their ratings of arousal or valence evoked by the alcohol‐associated and the affectively neutral stimuli, while non‐alcoholic beverages were rated as more unpleasant and more arousing by patients with AUDs. Although Wrase et al. (2002) validated neutral as well as alcohol‐related stimuli in subjects with AUDs as well as in controls, the small number of stimuli and the absence of objective stimulus descriptions (e.g. luminance) limit the use of their cues in experimental research requiring large numbers of physically standardized stimuli.

Stritzke, Breiner, Curtin, and Lang (2004) developed and evaluated pictures of 18 alcoholic beverages and 12 non‐alcoholic beverages, as well as other appetitive cues, in the Normative Appetitive Picture System (NAPS). During the evaluation procedure, undergraduate students rated the pictures with respect to arousal, as well as the intensity of the wish to consume (approach) or to avoid consuming (avoidance). Arousal ratings for the alcohol‐related cues increased as a function of drinking experience across abstainers, light drinkers, and heavy drinkers. Furthermore, drinking experience was also positively associated with approach ratings (i.e. craving) for alcohol cues. This fine‐grained examination advances our knowledge about the associations between stimulus types, individual reactions, and substance use history. Nevertheless, this information may only be of limited value for clinical AUD research, as the study population contained no patients with AUDs, but was composed of only young high‐functioning university students.

Billieux et al. (2011) used the emotional pictures validation procedure (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008) to develop a set of 60 alcohol‐related pictures, called the Geneva Appetitive Alcohol Pictures (GAAP). Risky drinkers and non‐risky drinkers did not differ in their ratings of valence. However, risky drinkers rated pictures of alcoholic beverages as more arousing compared to non‐risky drinkers. While the GAAP provides a large number of alcohol‐related stimuli, a direct comparison with non‐alcohol‐related (neutral) stimuli is lacking. This limits the use of GAAP stimuli in experimental settings in which both alcohol‐related and neutral stimuli are required to create different experimental conditions. Moreover, the sample included risky drinkers, but not inpatients with clinical AUDs. This restricts the generalization of stimulus validation results to non‐clinical populations.

In an attempt to create standardized stimulus material for use in a non‐drinking population, Pulido et al. (2010) recruited healthy young non‐drinkers and asked them to rate 60 pictures of alcoholic beverages and 60 pictures of non‐alcoholic beverages. In this sample, the arousal ratings did not differ between picture types, but pictures of non‐alcoholic beverages tended to be rated more pleasant than those of alcoholic beverages.

More recently, Pronk et al. (2015) presented the Amsterdam Beverage Picture Set (ABPS), which was established through a procedure in which heavy and light drinking psychology students completed rating and recognition tasks on 96 pictures. Here, compared to light drinkers, heavy drinkers reported a stronger urge to drink in response to the alcohol‐related pictures. Apart from the fact that the validation procedure was limited to a non‐clinical sample, the ABPS is a well‐validated picture set, and makes a valuable contribution to future alcohol research and cognitive bias measurements.

While these studies represent good examples of reasonable validation procedures resulting in the creation of valuable stimulus databases, none of them fulfills all of the requirements for experimental AUD research as described earlier. Most importantly, none of the studies provides a pool of both alcohol‐related and neutral stimuli (validated in healthy subjects and patients with clinical AUDs) that is large enough to avoid repetition effects in studies requiring repeated measures and/or high numbers of trial presentations. As mentioned earlier, this also limits the possibility of extracting individualized subsets of stimuli based on individual participants' characteristics, such as drinking context or drinking history.

The present report puts forward a comprehensive validation of a large database of alcohol‐related and neutral pictorial stimuli. Alcohol‐related stimuli consisted of photographs of alcoholic beverages. Neutral stimuli consisted of photographs of everyday objects. Pictures of non‐alcoholic beverages were excluded, as they may unintentionally trigger associations with alcoholic drinks (i.e. a picture of a Coke may evoke the cocktail whiskey and Coke), and because neutral beverages seem to be rated differently by patients with AUDs and healthy controls (Wrase et al., 2002). To maximize the value of this database for use in clinical settings, inpatients with AUDs who were hospitalized due to severe alcohol addiction rated the stimuli along with healthy controls. A rigorous stimulus standardization procedure was carried out to account for subjective, as well as objective, stimulus characteristics.

All pictures used in the present study, as well as a dataset describing each picture's properties (valence, arousal, craving, alcohol‐relatedness, visual complexity, luminance, and brightness in three red–green–blue [RGB] color channels), may be requested from the corresponding author for use in future studies.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

All pictures were viewed and rated by 18 inpatients with AUDs and 18 healthy controls. All patients (nine male, nine female; mean age 39.6 years, range 25–57) were recruited during inpatient treatment at the University Hospital of Psychiatry in Bern. At the time of the study, all patients had undergone detoxification and had been abstinent for at least six days (mean 32.9 days, range 6–100). Abstinence was checked by random alcohol testing of breath and urine. All patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for an alcohol dependence syndrome as their primary diagnosis according to the International Classification of Disease, 10th edition. Patients with a secondary psychiatric diagnosis (including other substance use disorders, mild or moderate depression, or anxiety) were included. The following secondary diagnoses were present in our sample in the following numbers (multiple diagnoses are possible): bipolar affective disorder =3; mild depressive or moderate depressive episode =9; psychosocial stress =2; emotionally unstable personality disorder =3; narcissistic personality disorder =2; panic disorder =1; substance use disorders, such as those for benzodiazepines =2, opiates =1, cocaine =2, or cannabis =2; and normal smoking or nicotine abuse =11. Subjects with neurological impairment were excluded.

Healthy controls (nine male, nine female; mean age 40.2 years, range 22–66) were recruited from the social environment of the research group. Healthy controls and patients with AUDs were matched for age and sex. To exclude volunteers with risky alcohol consumption, all controls filled in the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins‐Biddle, & Monteiro, 2001) prior to the rating procedure and subjects with a clinically relevant AUDIT score (> 8) were excluded (see also section 2.5).

2.2. Stimulus material

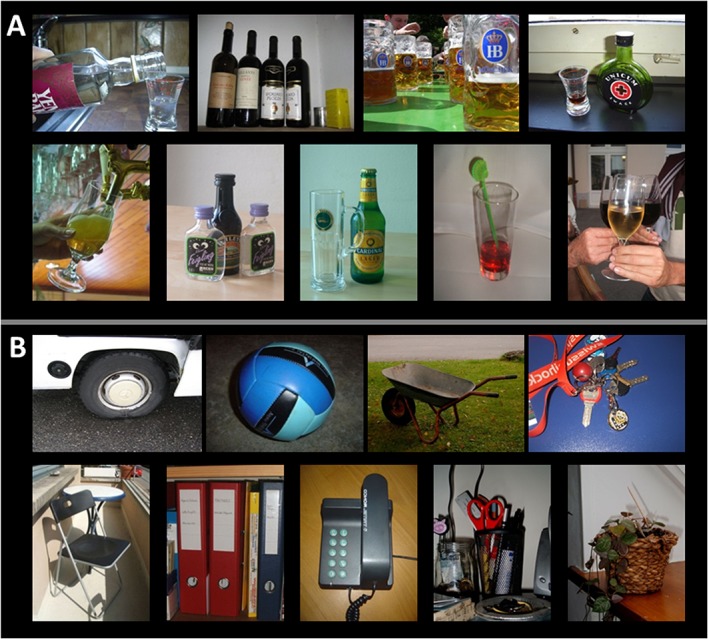

All pictures were captured by the authors using a Fujifilm F440 or a Sony DSC‐P92 digital camera. Out‐of‐focus pictures were excluded after a first visual inspection and quality control. Finally, 855 pictures were generated and included in the rating procedure (see Figure 1 for examples). Almost all neutral and alcohol‐related pictures were inanimate.

Figure 1.

Examples of alcohol‐related (A) and neutral pictures (B)

2.2.1. Alcohol‐related stimulus material

A total of 457 pictures showing alcohol‐related objects were generated and included in the rating procedure (Figure 1A). Alcohol‐related pictures depicted alcoholic beverages in drinking glasses or wine or beer bottles and alcohol‐related situations. Faces or identifiable individuals were not depicted. However, in some pictures, hands holding beverages or raising them to the mouth were displayed. The data set contains pictures of different beverage types, such as beer (N = 93), wine (N = 187), hard liquor (N = 143), and others (N = 34).

2.2.2. Neutral stimulus material

Overall, 398 neutral pictures were generated (Figure 1B). The objects in the neutral pictures may be classified as follows: nature and gardens (N = 25); fruits, vegetables, and other food (N = 16); buildings (N = 8); cleaning supplies (N = 15); kitchen (N = 61); bathroom (N = 34); office (N = 64); locomotion (N = 14); electronics (N = 40); habitation (N = 48); clothes (N = 23); and others (N = 50).

2.3. Study procedure

The study procedure was approved by the cantonal ethics committee. After informed consent, all participants were asked to fill in the AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) – German Version (Franke, 2000). During the rating procedure, the 855 pictures were presented in four blocks of 212 to 215 pictures. The subjects were allowed to take breaks between blocks if needed. The two picture types were distributed equally across the four blocks. The presentation order of the four blocks was balanced across subjects to control for order effects. Within each block, the presentation order of the pictures was randomized. A short exercise trial before the rating procedure was used to familiarize the participants with the computerized task and the rating scales. Each picture was rated for arousal, valence, alcohol‐relatedness, and craving (see section 2.4).

2.4. Subjective ratings

Valence and arousal were assessed using the Self‐Assessment Manikin (SAM; Bradley & Lang, 1994), a non‐verbal pictorial assessment technique that directly measures valence and arousal associated with a person's affective reaction to the presented stimulus. Possible SAM scores range from one to five. Higher scores represent more arousal and more positive valence on these scales. Alcohol‐relatedness and craving were measured using an 11‐point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 10. Here, higher scores represent greater alcohol‐relatedness or greater craving.

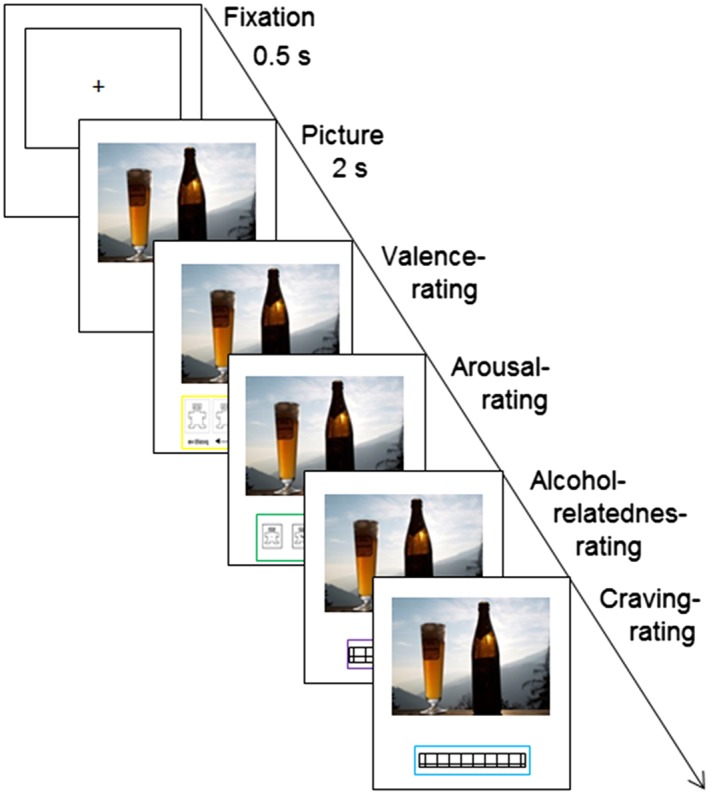

Figure 2 shows the sequence of steps used in the rating procedure. At first, a white screen with a black frame was presented for half a second to guide the participant's attention to the place where the picture was to be presented. The picture was then presented by itself for two seconds before the four questions and the rating scales were subsequently displayed below the picture. In this manner, the following four questions were answered for every picture:

Does this picture evoke positive or negative emotions? (valence, SAM)

Does this picture evoke strong or weak emotions? (arousal, SAM)

How much is this picture related to alcohol? (alcohol‐relatedness, Likert scale)

How strong is your wish/urge to drink alcohol? (craving, Likert scale)

Figure 2.

Sequence of the rating procedure

When one question was answered with a mouse click, the next question followed. After the fourth question, the frame for the next picture appeared on the screen. Picture presentation and collection of rating responses was conducted using Eprime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

Note that in the Results and Discussion section, we use the fourth question (“How strong is your wish/urge to drink alcohol?”) as an assessment of craving. Alcohol craving describes an emotional‐motivational state corresponding to a subjective feeling of a strong desire or need to consume alcohol in patients with AUDs. Craving is a technical term in addiction medicine and research and – conceptually – is a marker of alcohol‐related disorders. Therefore, by definition, it is not supposed to be observable in a healthy population. While fully aware of this fact, we nevertheless chose to refer to both groups' (patients and controls) ratings of question 4 as “craving,” as using the same term for both groups was deemed to improve reader understanding.

2.5. Diagnostic questionnaires

The AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001) is a simple, 10‐question screening method for excessive drinking and was employed in the present study to detect potentially risky alcohol‐drinking behavior in the control group. It was also used to quantify alcohol consumption and to assess addiction severity (Lundin, Haligren, Balliu, & Forsell, 2015) in the patient group.

AUDIT scores can range from 0 to 40, with scores higher than eight indicating a potential alcohol use problem (Reinert & Allen, 2002, 2007). Healthy controls with scores higher than 8 were excluded from this study. Because the patients with AUD were abstinent at the time of the study and were in a protected environment, they were requested to evaluate their general alcohol behavior during the period before their admission to the hospital.

The BSI (Derogatis, 1992), German version (Franke, 2000), a self‐report scale assessing psychopathological symptoms, was used in the present study to describe the level of psychological distress in our sample. The BSI yields nine subscales (e.g. depression, anxiety, psychoticism), as well as three global indices capturing global psychological distress. The Global Severity Index (GSI) is an index of general psychopathology. GSI values (T‐values) of ≥63 are considered to be clinically relevant (Franke, 2000).

2.6. Physical parameters

In addition to the rating procedure, luminance and color (red‐, green‐, and blue‐values) of all pictures were assessed using a MATLAB® script. Furthermore, because spatial frequency can be seen as an index of perceptual complexity (Bradley, Hamby, Low, & Lang, 2007), the visual complexity of every picture was assessed by spatial Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) using a MATLAB® script. The diagonal elements of the first quadrant of the FFT output (representing the positive frequencies) were multiplied with integers representing their position along the spatial frequency spectrum and divided by the sum of the diagonal elements to calculate the center of gravity of the spatial frequency spectrum of each image. This center of gravity was used as numeric index of visual complexity in all subsequent analyses.

2.7. Scrambled pictures

From every alcohol‐related picture, a corresponding scrambled picture was composed. Scrambled pictures were computed by electronically cutting up the picture into small blocks of 3 × 3 or 4 × 3 pixels and then randomly reassembling them. Scrambled alcohol‐related pictures and the original alcohol‐related pictures are thus perfectly matched with respect to luminance. Scrambled pictures were not subjected to the rating procedure, but can be obtained from the corresponding author if needed.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20/22 (SPSS©). Because AUDIT values, rating values, and physical parameters were not normally distributed (tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, all p ≤ 0.05), statistical comparisons of the subjective ratings (arousal, valence, craving, and alcohol‐relatedness) and the physical parameters (luminance, color, and visual complexity) were done using the Mann–Whitney U test.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Diagnostic questionnaires

As expected, there were significant differences in AUDIT and BSI scores between patients and healthy controls (Table 1), with patients with AUD having higher scores on both questionnaires.

Table 1.

Questionnaire scores: comparison between patients with AUDs and healthy controls

| Patients with AUDs | Healthy controls | t‐Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| Age | 39.61 | 9.67 | 40.22 | 12.36 | 0.17 | .870 |

| AUDIT | 24.11 | 6.43 | 3.89 | 1.94 | –12.76 | .000*** |

| BSI (GSI, T‐values) | 72.28 | 10.53 | 40.61 | 11.09 | –8,79 | .000*** |

Note: N = 36 (18 alcoholics, 18 healthy controls); M = mean; SD = standard deviation; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, cumulative score; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory, GSI = Global Severity Index, t‐test (two‐tailed).

p ≤ 0.001.

3.2. Subjective ratings (arousal, valence, craving, and alcohol‐relatedness)

Group comparisons between patients with AUDs and healthy controls indicated that neutral pictures evoke significantly more craving and more alcohol‐relatedness in patients with AUDs than in controls. Although not significant, there was a tendency for alcohol‐related pictures to evoke stronger arousal and craving in patients with AUD than in healthy controls (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Subjective rating values: comparison between patients with AUDs and healthy controls

| Valence | Arousal | Craving | Alc. rel. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alcpic | neupic | alcpic | neupic | alcpic | neupic | alcpic | neupic | |

| U score | 161.0 | 105.5 | 101.0 | 118.0 | 101.5 | 62.5 | 143.0 | 76.0 |

| p‐value | 0.975 | 0.074 | 0.054 | 0.164 | 0.055 | 0.001* | 0.548 | 0.006* |

| Patients with AUD MD | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 9.0 | 0.2 |

| (N = 18) SD | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| Healthy controls MD | 3.0 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 0.1 |

| (N = 18) SD | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.2 |

Note: MD = median; SD = standard deviation; alcpic = alcohol‐related pictures; neupic = neutral pictures; Alc. rel. = alcohol‐relatedness. U Test (two‐tailed) with p corrected for multiple comparisons.

p corrected < 0.05 (i.e. p < 0.001).

Comparisons between alcohol‐related and neutral pictures indicated that in all subjects, alcoholic pictures evoked higher arousal, were more alcohol‐related, evoked more craving, and had more negative valences compared to neutral pictures (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subjective rating values: Comparison between alcohol‐related pictures and neutral pictures before and after outlier removal

| Valence | Arousal | Craving | Alc. rel. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before outlier removal | ||||

| U score | 48440.5 | 31634.5 | 7.0 | 0.0 |

| p‐Value | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Alcohol‐related pictures MD | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 8.0 |

| (N = 457) SD | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Neutral pictures MD | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| (N = 398) SD | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| After outlier removal | ||||

| U score | 44334.5 | 29252.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| p‐Value | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Alcohol‐related pictures MD | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 8.1 |

| (N = 444) SD | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Neutral pictures MD | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| (N = 387) SD | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

Note: N = number of pictures; MD = median; SD = standard deviation; Alc. rel. = alcohol‐relatedness. U Test (two‐tailed) with p corrected for multiple comparisons.

Indicates p corrected < 0.001 (i.e. p < 0.00025).

3.3. Outlier removal

To supply future researchers with a set of stimuli of ensured validity, we removed outliers from our original set of 855 pictures. An alcoholic picture was considered an outlier if its result on the craving scale was lower than the maximal craving results of the neutral pictures or if its rated alcohol‐relatedness was 2.6 standard deviations below the mean of all alcohol‐related pictures. A neutral picture was considered an outlier if its result on the craving scale was higher than the minimal craving results of the alcoholic pictures or if its rated alcohol‐relatedness was 2.6 standard deviations above the mean of all neutral pictures. After outlier removal, 444 alcohol‐related pictures and 387 neutral pictures (thus a total of 831 pictures) remained in the data pool. In this final data set, the mean rating values of the alcohol‐related pictures still indicated significantly higher arousal, more craving, more alcohol‐relatedness, and more negative valences than those of the neutral pictures (Table 3).

3.4. Physical parameters

We assessed the physical parameters (luminance, complexity, and color values for red, green, and blue) of pictures in our final stimulus set (N = 831 after outlier removal). Table 4 shows the differences in these parameters between alcohol‐related pictures and neutral pictures before corrections for luminance and color.

Table 4.

Physical parameters before and after adjustment: comparison between alcohol‐related pictures and neutral pictures

| Com | Lum | Red | Gre | Blu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adjustment | |||||

| U score | 81152 | 53858.5 | 61375 | 54053 | 57.499 |

| p‐Value | 0.168 | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| Alcohol‐related pictures MD | 25.3 | 93.8 | 108.2 | 95.1 | 76.3 |

| (N = 444) SD | 8.8 | 23.4 | 27.2 | 23.8 | 28.7 |

| Neutral pictures MD | 23.8 | 106.9 | 121.6 | 110.8 | 94.9 |

| (N = 387) SD | 13.0 | 30.5 | 32.5 | 32.7 | 39.0 |

| After adjustment | |||||

| U score | 81349 | 77243.5 | 84809 | 77453.5 | 75813 |

| p‐Value | 0.186 | 0.012 | 0.749 | 0.014 | 0.003* |

| Alcohol‐related pictures MD | 25.5 | 98.0 | 112.3 | 99.2 | 81.7 |

| (N = 444) SD | 8.9 | 21.5 | 24.1 | 22.5 | 27.7 |

| Neutral pictures MD | 23.9 | 101.5 | 112.2 | 102.6 | 85.7 |

| (N = 387) SD | 13.0 | 19.9 | 26.1 | 22.4 | 28.9 |

Note: physical parameters were analyzed after outlier removal and thus only describe the final stimulus pool containing 831 pictures. N = number of pictures; MD = median; SD = standard deviation; Com = complexity; Lum = luminance; Gre = brightness in the green channel; Blu = brightness in the blue channel. U Test (two–tailed) with p corrected for multiple comparisons.

Indicates p corrected < 0.05 (i.e. p < 0.01).

From the final set of 831 stimuli (after outlier removal), 130 stimuli with extreme values were then selected and their luminance and/or color values were adjusted. This was done with the aim of facilitating the construction of luminance‐ and color‐matched sets in future research projects. As shown in Table 4, luminance and color values did not differ between the neutral and alcohol‐related pictures after this adjustment, except for the color value “blue.” Interested researchers may request the adjusted set of 831 stimuli from the corresponding author.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to develop a large dataset of alcohol‐related and neutral pictures to supply future research projects with well‐validated stimulus material. Inpatients with AUDs and healthy controls rated more than 850 photographs especially captured for this purpose on different relevant affective and perceptual characteristics (valence, arousal, craving, and alcohol‐relatedness). Rating values were compared between groups and between picture types. Furthermore, physical stimulus parameters such as visual complexity, luminance, and color were extracted, and a subset of stimuli with extreme values was normalized to minimize mean differences between alcoholic and neutral stimuli. After outlier removal, 831 well‐evaluated pictures remained in the stimulus pool (444 alcohol‐related pictures and 387 neutral pictures).

As required in stimulus validation studies (Billieux et al., 2011; Pulido et al., 2010), multiple relevant affective and perceptual stimulus parameters were assessed and controlled for in a single validation procedure. Based on our definition of stimulus validity, we required that alcohol‐related and non‐alcohol‐related (neutral) stimuli consistently produce differences in perceived alcohol‐relatedness and craving (but see Pronk et al., 2015, for a different operationalization). Both criteria were met by the stimuli under investigation: pictures of alcoholic beverages evoked significantly higher craving and were clearly rated as more alcohol‐related than neutral stimuli. These analyses were conducted using ratings from both groups (patients and controls). It may however be of interest to researchers aiming to use this stimulus set in clinical populations that both criteria were also met when only patient data were considered in the analyses.

The resulting large database allows for not only the selection of specific alcohol‐related pictures (different types of drinks and alcohol‐related contexts individualized for each patient), but also for the composition of multiple comparable but non‐overlapping stimulus sets to avoid repetition effects. This is an important advantage for neurophysiological studies (Luck, 2014; Myrick et al., 2008). Moreover, the fact that inpatients with severe AUDs and long drinking histories provided ratings of subjective stimulus features makes the stimulus set particularly suited for clinical investigations. The earlier features of the database indicate that its use will lead to a reliable estimation of cue‐related processes in patients.

In a comparison of the ratings of alcohol‐related versus neutral photographs, several picture type differences were found. Pictures of alcoholic beverages were – as expected – rated as much more alcohol‐related than neutral pictures. Furthermore, alcohol‐related pictures provoked stronger craving and higher arousal and were rated as more negative than neutral pictures. These results are in accordance with earlier studies that also compared the alcohol‐relatedness (Wrase et al., 2002), valence (Ihssen, Cox, Wiggett, Fadardi, & Linden, 2011; Pulido et al., 2010), and arousal (Ihssen et al., 2011) of alcohol‐related pictures to those of neutral pictures. However, other studies have not observed significant differences in arousal ratings (Pulido et al., 2010). The divergent results concerning arousal ratings may be due to differences in the study population (non‐drinking individuals versus heavy drinkers versus clinical population) or the control condition (non‐alcoholic beverages versus neutral objects, excluding beverages).

In addition to the main analyses focusing on picture type comparisons to establish stimulus validity, we conducted an exploratory comparison of the two participant groups. When comparing the subjective ratings from patients with AUDs to those of healthy controls, only small or no between‐group differences emerged. This is consistent with earlier studies reporting similar valence (Billieux et al., 2011; Ihssen et al., 2011; van Duijvenbode, Didden, Bloemsaat, & Engels, 2012; Wrase et al., 2002) and arousal (Ihssen et al., 2011; Wrase et al., 2002) ratings by individuals with and without a history of alcohol use‐related problems. However, in the study by Billieux et al. (2011), risky drinkers rated pictures of alcoholic beverages as more arousing compared to non‐risky drinkers.

Comparing craving and alcohol‐relatedness ratings between the participant groups, we observed no significant differences between the alcohol‐related pictures. Even if the patients with AUDs reported slightly more craving than controls when looking at alcohol‐related pictures, this effect was very small (Cohen's d = 0.11). Previous studies (Pronk et al., 2015) reported larger effects when comparing the urge to drink in response to alcohol‐related pictures in (highly functioning) heavy drinkers vs. light drinkers. This divergence may be due to differences in the populations providing the ratings (light and heavy drinking psychology students in the Pronk study versus inpatients with severe AUDs and healthy controls in the present study). It is possible that inpatients with severe AUDs taking part in an abstinence‐oriented treatment react with emotional downregulation or social desirability responses to alcohol‐related pictures. The comparably high standard deviation in our patient group is in line with the assumption that this may be the case at least in a part of our patient group (see also limitations). When looking at neutral pictures, patients with AUDs experienced more craving than healthy controls and rated the neutral pictures as more alcohol‐related than the healthy controls did. However, this finding has to be interpreted in light of the generally very low self‐reported craving and the extremely low alcohol‐relatedness scores of the neutral pictures. Most likely, it resulted from the fact that some patients with AUDs perceived alcohol‐related aspects even in the neutral pictures. The earlier finding may also be because patients with AUDs were generally more activated in terms of alcohol cue‐reactivity during the trials.

Taken together, the results from our rating procedure indicate differences between picture types but not between groups. Although one might argue that the similarity of the ratings by the patients with AUDs and those by healthy controls limits the face validity of the stimulus set, the absence of group effects indicates that the stimuli are comparable between groups. The good comparability of the stimuli would be an advantage in future (neurophysiological) studies.

The fact that the validation of the pictures was based on self‐reports and did not include additional physiological measurements is a limitation of this study, as some participants' responses may have been biased by social desirability. Furthermore, patients with AUDs could have learned during treatment to react with avoidance or emotional downregulation after a first appetitive reaction to the alcohol‐related pictures. In future research, it could be very interesting and revealing to complement the present ratings with neurophysiological or psychophysiological measurements, such as skin conductance responses. Moreover, the lack of personalization of stimulus sets on the basis of a participant's drinking preferences can be considered a limitation (Tapert et al., 2003). In our study, all participants evaluated all pictures, irrespective of the match between their drinking preference and the beverage type depicted and it can be assumed that the patients' ratings varied with the extent of this match. This effect may be one reason for the rather low median of the craving ratings found here. In spite of this limitation, we chose the present procedure as an initial validation, as it allowed us to establish a large, evaluated database from which personalized sets can be composed in future studies.

As mentioned earlier, participants were recruited during inpatient treatment at the University Hospital of Psychiatry and had diverse comorbidities, which may have had an influence on their subjective stimulus ratings. At the same time, this heterogeneity within the patient sample represents a good approximation of clinical reality, where most patients with AUDs suffer from comorbid disorders. The present patient sample was carefully evaluated and diagnosed as having severe AUDs, so that the present findings hold especially true for populations with relatively long histories of alcohol consumption and alcohol‐related problems. It is likely that cognitive processes differ in dependence of the duration of the drinking history (Kreusch et al., 2013). The present results thus do not apply without constraint to light or social drinkers, binge‐drinkers, or adolescents. Finally, the small sample size is a limitation of our study, as only a relatively small number of participants rated the subjective characteristics of the stimuli. This may have limited the detection of statistically significant differences between groups and the generalizability of the present findings. Future studies, especially those concerned with between‐group effects, should include larger samples of patients with AUDs.

In summary, the presented database contains a large number of alcohol‐related and neutral pictures. These pictures are not only validated with respect to relevant subjectively rated affective and perceptual properties, but have also been well described regarding their physical parameters. All pictures, together with a dataset containing the rating values (valence, arousal, craving, and alcohol‐relatedness), as well as the physical parameters (visual complexity, luminance, and RGB values), can be obtained from the corresponding author. This will allow interested researchers to choose the most appropriate stimuli for their specific objectives. We hope that these stimuli make a valuable contribution to future research on the development, maintenance, and therapy of AUDs.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the patients and healthy controls who participated in this study! Furthermore, they express their gratitude to the team on ward “Flügel” at the University Hospital of Psychiatry in Bern for their valuable help in recruitment.

Fey W, Moggi F, Rohde KB, Michel C, Seitz A, Stein M. Development of stimulus material for research in alcohol use disorders. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1527 10.1002/mpr.1527

REFERENCES

- Babor, T. F. , Higgins‐Biddle, J. C. , & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). AUDIT – The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines of Use in Primary Health Care, Genf: WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6a. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Billieux, J. , Khazaal, Y. , Oliveira, S. , Timary de, P. , Edel, Y. , Zebouni, F. , … Van der Linden, M. (2011). The Geneva Appetitive Alcohol Pictures (GAAP): Development and preliminary validation. European Addiction Research, 17(5), 225–230. doi: 10.1159/000328046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D. , Mellenbergh, G. J. , & Van Heerden, J. (2004). The concept of validity. Psychological Review, 111(4), 1061–1071. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.4.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M. M. , & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The Self‐Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(3), 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M. M. , Hamby, S. , Low, A. , & Lang, P. J. (2007). Brain potentials in perception: Picture complexity and emotional arousal. Psychophysiology, 44(3), 364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman, J. F. , White, H. R. , & Bates, M. E. (2010). Psychophysiological reactivity to emotional picture cues two years after college students were mandated for alcohol interventions. Addictive Behaviors, 35(8), 786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1992). BSI: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual – II. Townson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dickter, C. L. , Forestell, C. A. , Hammett, P. J. , & Young, C. M. (2013). Relationship between alcohol dependence, escape drinking, and early neural attention to alcohol‐related cues. Psychopharmacology (Berlin), 231(9), 2031–2040. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3348-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddie, D. , Buckman, J. F. , Mun, E. Y. , Vaschillo, B. , Vaschillo, E. , Udo, T. , … Bates, M. E. (2013). Different associations of alcohol cue reactivity with negative alcohol expectancies in mandated and inpatient samples of young adults. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 2040–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke, H. G. (2000). Brief Symptom Inventory of L. Derogatis. Short Version of SCL‐90‐R – German Version. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Garavan, H. , Pankiewicz, J. , Bloom, A. , Cho, J. K. , Sperry, L. , Ross, T. J. , … Stein, E. A. (2000). Cue‐induced cocaine craving: neuroanatomical specificity for drug users and drug stimuli. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(11), 1789–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüsser, S. M. , Heinz, A. , & Flor, H. (2000). Standardized stimuli to assess drug craving and drug memory in addicts. Journal of Neural Transmission, 107, 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüsser, S. M. , Wrase, J. , Klein, S. , Hermann, D. , Smolka, M. N. , Ruf, M. , … Heinz, A. (2004). Cue‐induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berlin), 175(3), 296–302. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1828-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, A. , Wrase, J. , Kahnt, T. , Beck, A. , Bromand, Z. , Grüsser, S. M. , … Mann, K. (2007). Brain activation elicited by affectively positive stimuli is associated with a lower risk of relapse in detoxified alcoholic subjects. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(7), 1138–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihssen, N. , Cox, W. M. , Wiggett, A. , Fadardi, J. S. , & Linden, D. E. (2011). Differentiating heavy from light drinkers by neural responses to visual alcohol cues and other motivational stimuli. Cerebral Cortex, 21(6), 1408–1415. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreusch, F. , Vilenne, A. , & Quertemont, E. (2013). Response inhibition toward alcohol‐related cues using an alcohol go/no‐go task in problem and non‐problem drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 38(10), 2520–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, P. J. , Bradley, M. M. , & Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). The International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual, Technical Report A‐8. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, S. J. (2014). An Introduction to the Event‐related Potential Technique (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, S. E. , Lowen, S. B. , Lindsey, K. P. , Conn, N. , Tartarini, W. , Rodolico, J. , … Penetar, D. M. (2013). Extended‐release naltrexone (XR‐NTX) attenuates brain responses to alcohol cues in alcohol‐dependent volunteers: a bold FMRI study. NeuroImage, 78, 176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin, A. , Hallgren, M. , Balliu, N. , & Forsell, Y. (2015). The use of alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in detecting alcohol use disorder and risk drinking in the general population: validation of AUDIT using schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(1), 158–165. doi: 10.1111/acer.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. A. , & Fillmore, M. T. (2010). The effect of image complexity on attentional bias towards alcohol‐related images in adult drinkers. Addiction, 105(5), 883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02860.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick, H. , Anton, R. F. , Li, X. , Henderson, S. , Randall, P. K. , & Voronin, K. (2008). Effect of naltrexone and ondansetron on alcohol cue‐induced activation of the ventral striatum in alcohol‐dependent people. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(4), 466–475. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson, J. K. , & Polich, J. (2007). Affective visual event‐related potentials: arousal, repetition, and time‐on‐task. Biological Psychology, 75(1), 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk, T. , van Deursen, D. S. , Beraha, E. M. , Larsen, H. , & Wiers, R. W. (2015). Validation of the Amsterdam Beverage Picture Set: A Controlled Picture Set for Cognitive Bias Measurement and Modification Paradigms. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(10), 2047–2055. doi: 10.1111/acer.12853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, C. , Brown, S. A. , Cummins, K. , Paulus, M. P. , & Tapert, S. F. (2010). Alcohol cue reactivity task development. Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, D. F. , & Allen, J. P. (2002). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): a review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(2), 272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, D. F. , & Allen, J. P. (2007). The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(2), 185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. E. , Wright, C. I. , Shin, L. M. , Kagan, J. , Whalen, P. J. , McMullin, K. G. , & Rauch, S. L. (2003). Differential amygdalar response to novel versus newly familiar neutral faces: a functional MRI probe developed for studying inhibited temperament. Biological Psychology, 53(10), 854–862. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01906-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke, W. G. K. , Breiner, M. J. , Curtin, J. J. , & Lang, A. R. (2004). Assessment of Substance Cue Reactivity: Advances in Reliability, Specificity, and Validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(2), 148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert, S. F. , Cheung, E. H. , Brown, G. G. , Frank, L. R. , Paulus, M. P. , Schweinsburg, A. D. , … Brown, S. A. (2003). Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 727–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvenbode, N. , Didden, R. , Bloemsaat, G. , & Engels, R. C. (2012). Problematic alcohol use and mild intellectual disability: standardization of pictorial stimuli for an alcohol cue reactivity task. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(4), 1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollstädt‐Klein, S. , Loeber, S. , Kirsch, M. , Bach, P. , Richter, A. , Buhler, M. , … Kiefer, F. (2011). Effects of cue‐exposure treatment on neural cue reactivity in alcohol dependence: a randomized trial. Biological Psychology, 69(11), 1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers, R. W. , Bartholow, B. D. , van den Wildenberg, E. , Thush, C. , Engels, R. C. M. E. , Sher, K. J. , … Stacy, A. W. (2007). Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 86(2), 263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase, J. , Grüsser, S. M. , Klein, S. , Diener, C. , Hermann, D. , Flor, H. , … Heinz, A. (2002). Development of alcohol‐associated cues and cue‐induced brain activation in alcoholics. European Psychiatry, 17(5), 287–291. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(02)00676-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase, J. , Schlagenhauf, F. , Kienast, T. , Wüstenberg, T. , Bermpohl, F. , Kahnt, T. , … Heinz, A. (2007). Dysfunction of reward processing correlates with alcohol craving in detoxified alcoholics. NeuroImage, 35(2), 787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]