Abstract

Background

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery has become the standard of treatment for rectal villous adenomas. However, the role of preoperative imaging for these lesions is not clear. The aim of this study was to compare the value of preoperative imaging and surgeon clinical staging in the preoperative evaluation of patients with rectal villous adenomas having transanal endoscopic microsurgery resection.

Methods

We conducted a single-centre comparative retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery surgery for rectal villous adenomas from 2011 to 2013. The intervention was preoperative imaging versus surgeon clinical staging. The primary outcome was the accuracy of clinical staging by preoperative imaging and surgeon clinical staging according to the histopathologic staging.

Results

A total of 146 patients underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery surgery for rectal villous adenomas. One hundred and twelve (76.7%) of those patients had no preoperative imaging while 34 patients (23.3%) had either endorectal ultrasound (22 patients) or magnetic resonance imaging (12 patients). Surgeon staging was accurate in 89.3% of cases whereas staging by endorectal ultrasound was accurate in 40.9% cases and magnetic resonance imaging was accurate in 0% of cases. In the imaging group, inaccurate staging would have led to unnecessary radical surgery in 44.0% of patients.

Conclusion

This study was subject to selection bias because of its retrospective nature and the limited number of patients with imaging. Patients with rectal villous tumours without invasive carcinoma on biopsies and without malignant characteristics on appearance in the judgment of an experienced colorectal surgeon might not benefit from preoperative imaging before undergoing transanal endoscopic microsurgery procedures.

Abstract

Contexte

La microchirurgie endoscopique transanale est devenue le traitement standard des adénomes villeux rectaux. La valeur de l’imagerie préopératoire pour le traitement de ces lésions n’est toutefois pas bien établie. Cette étude visait à comparer l’exactitude de la stadification par imagerie préopératoire et de la stadification clinique par le chirurgien dans le cadre de l’évaluation préopératoire des patients atteints d’adénomes villeux rectaux qui subissent une résection par microchirurgie endoscopique transanale.

Méthodes

Nous avons mené une étude de cohorte rétrospective comparative monocentrique chez des patients ayant subi une microchirurgie endoscopique transanale pour un adénome villeux rectal entre 2011 et 2013. Les interventions comparées étaient la stadification par imagerie préopératoire et la stadification clinique par le chirurgien. L’issue principale était l’exactitude de la stadification clinique par imagerie préopératoire et de la stadification clinique par le chirurgien, confirmée par stadification histopathologique.

Résultats

Au total, 146 patients ont subi une microchirurgie endoscopique transanale pour le traitement d’un adénome villeux rectal. De ces patients, 112 (76,7 %) n’avaient pas subi d’imagerie préopératoire et 34 (23,3 %) avaient subi une échographie endorectale (22 patients) ou une imagerie par résonance magnétique (12 patients). La stadification par le chirurgien était exacte dans 89,3 % des cas, contre 40,9 % des cas pour l’échographie endorectale et 0 % des cas pour l’imagerie par résonnance magnétique. Dans le groupe ayant subi une imagerie, l’inexactitude de la stadification aurait mené à une chirurgie radicale inutile pour 44,0 % des patients.

Conclusion

Cette étude comportait un biais de sélection en raison de sa nature rétrospective et du nombre limité de patients ayant subi une imagerie. L’imagerie préopératoire avant une microchirurgie endoscopique transanale pourrait ne présenter aucun avantage pour les patients présentant des tumeurs villeuses rectales dans les cas où aucun carcinome invasif n’a été détecté par biopsie et où un chirurgien colorectal chevronné n’a détecté aucune caractéristique maligne.

With incidence ranging from 23% to 58% in adults, adenomas are the most common type of neoplasm in the colon and rectum.1 They are considered premalignant lesions that can grow in size, become increasingly dysplastic and eventually develop into carcinoma.3 The rate of progression to invasive adenocarcinoma varies according to histologic type, size and grade of dysplasia.2,4 Villous adenomas represent 10% of all colorectal adenomas and are found mostly in the rectum, where they comprise 40%–66% of all tumours.3,5

Introduced 30 years ago by Buess, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) was initially designed to improve results in local excision of rectal adenomas.6 It has since become the treatment of choice for large rectal villous tumours and a valuable option for selected early rectal cancers. TEM has been shown to be associated with lower rates of positive margin, specimen fragmentation and recurrence when compared with conventional transanal excision.7 Authors have concluded that nearly all rectal adenomas can be removed safely with TEM throughout the entire rectum.8–13

Up to 34% of rectal villous adenomas presumed to be benign on biopsies will harbour invasive adenocarcinoma on final pathology.14,15 A proportion of these patients would then be offered additional radical surgery to achieve node clearance. Morino and colleagues have reported an increased rate of abdominoperineal excision for patients having completion radical resection after TEM, making preoperative diagnosis crucial.16 Some have recommended that all these rectal lesions should undergo preoperative staging similar to invasive carcinomas with either endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to improve patient selection for TEM.17 However, the risk of inadequate upstaging by these investigative tools may mean that patients are subjected to unnecessary radical surgery. Hence, we believe preoperative imaging is unnecessary for TEM when the tumour appears benign and biopsies are negative for invasive adenocarcinoma.

The purpose of this study was to compare the value of ERUS and MRI with the value of surgeon clinical staging in the preoperative evaluation of patients with rectal villous adenomas having TEM resection.

Methods

All consecutive patients who underwent TEM resection for any diagnosis (adenoma, adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumours and gastrointestinal stromal tumours) from April 2011 to September 2013 at Hôpital Saint-François-d’Assise were included. All patients underwent preoperative investigation, which included digital rectal examination, colonoscopy with tumour biopsies and rigid rectoscopy, by 1 of the colorectal surgeons performing TEM. On the basis of the tumour morphology, mobility, pit pattern, friability, feel on digital rectal examination (if possible) and presence or not of a central ulcer, the 3 surgeons performing TEM at our institution used their experience and clinical judgment to determine if the tumour appeared benign. If it did and the biopsies were negative, no further imaging was warranted. Patients with biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma underwent further preoperative imaging with either ERUS or MRI. Some patients had upfront preoperative imaging at their referring centre, irrespective of their biopsy result. In general, patients who had biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma at clinical stage cT1 with adverse prognostic factors on biopsy (lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, tumoral emboli or poor differentiation), cT2 or cT3 were offered radical surgery, while patients with benign adenomas and selected cT1 tumours were offered TEM resection. Patients for whom biopsies were benign and radiologic investigation suggested invasive carcinoma were managed according to the judgment of the treating surgeon, with further investigation when deemed appropriate.

All procedures were performed by 1 of the 3 colorectal surgeons doing TEM resection at our institution. All 3 surgeons had received training in TEM during their fellowships and were performing a high volume of TEM at our centre, with close to 100 cases per year (for the 3 surgeons combined) since 2011. Transmural excisions aiming for a 1-cm macroscopic margin were performed using the TEM platform (Wolf-Ultramed). Rectal wall defects were closed primarily, when possible, with multiple running 3.0 Maxon sutures. Defects were left open for secondary healing when closure was not possible or when it was suboptimal.

Standardized chart review was performed by a single reviewer (A.S.L.). Cancers were staged using the TNM classification system, according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual. 18 To obtain our primary outcome, we compared final pathologic stages (pT) with preoperative stages (cT) to determine the accuracy of surgeon, ERUS and MRI staging in this setting. The secondary outcome was defined as the proportion of patients who would have had unnecessary radical surgery on the basis of preoperative imaging.

Results

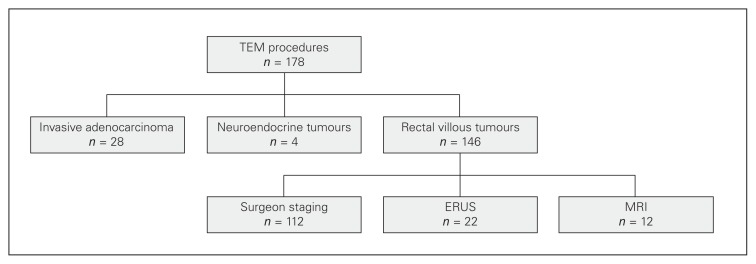

A total of 178 patients underwent TEM procedures from April 2011 to September 2013. Thirty-two patients (18.0%) had a preoperative biopsy-proven diagnosis of cancer with either invasive adenocarcinoma (28 patients) or neuroendocrine tumours (4 patients). The 28 patients with invasive adenocarcinoma underwent TEM resection for polypectomy scar excision with positive margins (17 patients) or for early tumour (11 patients) while the 4 patients with neuroendocrine tumours had TEM for positive margin on endoscopic polypectomy. The 146 remaining patients had a preoperative diagnostic of rectal villous adenoma. Of those, 112 patients (76.7%) had no preoperative imaging, 22 patients (15.1%) had preoperative ERUS and 12 patients (8.2%) had preoperative MRI. Preoperative imaging in patients without adenocarcinoma on biopsy was done in referring centres before the referral as no preoperative imaging was deemed necessary at our centre if the lesion appeared benign and biopsies were negative. The choice of ERUS versus MRI was made by the referring surgeon. A flow diagram of the patients in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram. ERUS = endorectal ultrasound; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; TEM = transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

Preoperative staging and final staging are compared in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. Of the 146 patients with no preoperative diagnosis of invasive cancer, 123 (84.2%) had rectal villous adenomas without foci of invasive carcinoma on final pathology. Twenty-two patients (15.1%) were upstaged to pT1 and 1 (0.6%) was upstaged to pT2 rectal adenocarcinoma on final pathology

Table 1.

Comparison of preoperative staging without imaging and final pathologic staging

| Preoperative stage | Pathologic stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0/Tis | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| T0/Tis | 100 | 12 | — | — | — |

| T1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T3 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T4 | — | — | — | — | — |

Table 2.

Comparison of preoperative staging with ERUS and final pathologic staging

| Preoperative stage | Pathologic stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0/Tis | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| T0/Tis | 6 | 1 | — | — | — |

| T1 | 8 | 3 | 1 | — | — |

| T2 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — |

| T3 | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| T4 | — | — | — | — | — |

ERUS = endorectal ultrasound.

Table 3.

Comparison of preoperative staging with MRI and final pathologic staging

| Preoperative stage | Pathologic stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0/Tis | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| T0/Tis | — | — | — | — | — |

| T1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T2 | 5 | 3 | — | — | — |

| T3 | 3 | 1 | — | — | — |

| T4 | — | — | — | — | — |

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Patients with a preoperative diagnosis of rectal villous adenoma were divided into 3 groups according to their modality of preoperative staging: no imaging, ERUS or MRI. In the 112 patients with no preoperative imaging, final pathology revealed only villous adenoma according to preoperative staging in 100 patients (89.3%) and 12 patients (10.7%) were upstaged (Table 1). These patients all had pT1 adenocarcinoma. Five of these patients underwent additional oncologic resection: 4 underwent low anterior resections and 1 underwent abdominoperineal resection because their lesions presented adverse features. All surgeries were done with minimally invasive surgery. Additionally, 1 patient had adjuvant chemoradiation and 2 patients had adjuvant chemotherapy.

Of the 22 patients in the ERUS group, 9 (40.9%) were adequately staged, 11 (50.0%) were overstaged and 2 (9.1%) were understaged (Table 2). On final pathology, only 7 specimens (31.8%) revealed invasive carcinoma while 15 (68.2%) were predicted to be invasive on preoperative ERUS. Six of the 7 patients with invasive cancer had a preoperative ERUS report compatible with cancer although only 3 had the same cT as pT stage.

Of the 12 patients who had preoperative MRI scans, all were overstaged (Table 3). All 12 patients had been diagnosed by MRI with stage T2 or T3 cancer but the tumours for only 4 of these patients were found to have an invasive component on final pathology. The 4 patients with cancer all had stage pT1 disease and none of them required additional treatment, as their TEM resection was adequate. If the results of the MRI scans had been used to decide the patients’ treatment, all would have had radical resection, low anterior resection or even abdominoperineal resection even though none of them required additional resection after TEM in our study.

Table 4 illustrates the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio of each modality. Considering that the majority of patients with T1 disease would be initially adequately treated with local excision, the use of preoperative imaging would have led to unnecessary radical resection in 44.1% (15/34) of patients having ERUS or MRI in our cohort. Overall, ERUS overstaged half of the patients and MRI overstaged all patients.

Table 4.

Comparison of the accuracy of each modality of staging*

| Measure | Surgeon staging | ERUS | MRI | Imaging (ERUS or MRI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 0 (0–30) | 86 (42–99) | 100 (39–100) | 91 (57–99) |

| Specificity, % | 100 (95–100) | 40 (17–67) | 0 (0–40) | 26 (11–49) |

| Positive predictive value,% | — | 40 (17–67) | 33 (11–65) | 37 (20–58) |

| Negative predictive value, % | 89 (92–94) | 86 (42–99) | — | 63 (42–80) |

| Positive likelihood ratio | — | 0.66 (0.32–1.40) | 0.5 (0.20 – 1.22) | 0.59 (0.33 – 1.04) |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.12 (0.07 – 0.21) | 0.17 (0.03 – 1.07) | — | 0.17 (0.03 – 1.07) |

ERUS = endorectal ultrasound; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Values are reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

TEM offers an alternative to more extensive resection for patients with rectal villous adenomas and selected T1 cancer as it reduces surgical trauma and potential complications and offers better functional results.19 TEM has been shown to be associated with low complication rates (1.2%–8.1%), the vast majority of which are minor.20–22 On the other hand, radical surgery for rectal neoplasms leads to complications in 20%–40% of cases and up to 80% of patients experience altered gastointestinal, sexual and urinary function.23,24 The main advantages of TEM include the possibility of excising rectal neoplasms up to 20 cm from the anal verge25 and more precise excision with consequent reductions in local recurrences rates.17,26,27 However, for cancer invading the muscularis propria (T2 or more), TEM resection is associated with high rates of recurrence and these patients should be offered more than TEM alone.28,29

There is no doubt that preoperative staging is 1 of the most important components of the workup of patients with rectal tumours. The treatment they are offered could change from a local excision to neoadjuvant chemoradiation and radical resection on the basis of preoperative staging. There is a risk of undertreatment and cancer recurrence if the appropriate treatment is not chosen, but there is also a risk of submitting a patient to inappropriate radical treatment if their disease is overstaged.

ERUS and MRI have proven to be powerful tools for the preoperative staging of rectal cancers. They accurately assess the local depth of tumour invasion and are able to evaluate mesorectal lymph nodes. The most important anatomic structure on which preoperative diagnosis is based is the lamina muscularis propria, which represents the watershed for lesions suitable for local excision with curative intent. A recent systematic review of the literature19 found that ERUS was more accurate (82% v. 78%) than MRI at characterizing early localized rectal cancers measured by the capacity to correctly detect muscularis propria invasion.30–34

One of the main limitations of preoperative imaging is the differentiation between benign rectal villous adenomas and T1 adenocarcinomas. In a study by Zorcolo and colleagues aimed at evaluating the role of preoperative ERUS in staging for TEM procedures, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as cT1 while half of pT1 cancers were interpreted as cT0.35 In another important series, Doornebosch and colleagues evaluated 268 presumed benign tumours referred for TEM.17 ERUS was intended in all tumours to be preoperative staging. Fifty-eight tumours (21.6%) were excluded because they either were not assessable (37 tumours) or had inconclusive results. Of the remaining 210 tumours, definite histopathologic staging revealed villous adenomas in 166 tumours (79.0%) and rectal carcinoma in 44 tumours (21.0%). On the basis of preoperative biopsy, no tumour would have been undertreated with TEM, whereas on the basis of ERUS, 19 (9.0%) ultrasonically presumed cT2/cT3 carcinomas would have been overtreated.

Our results confirm the difficulty of differentiating between benign rectal villous adenomas and lesions with foci of invasive carcinomas. In our series, 15.7% of tumours were found to have invasive adenocarcinoma on final pathology, which is comparable with results found in the literature. 14,15,17 ERUS had high sensitivity in accurately demonstrating submucosal invasion (85.7%). However, it overstaged 50.0% of the lesions, which meant that these patients were at risk of overtreatment. This number is much higher than in the series discussed in the previous paragraph. As ERUS is operator dependent, this discrepancy is probably explained by the fairly small number of ERUS procedures performed in our series. MRI also correctly detected all cases of submucosal invasion but overstaged all 12 cases. If one considers that rectal villous adenoma and most T1 lesions can be treated with local excision and that more advanced lesions such as those at stage T2 and T3 should have a radical resection, clinical decisions based on ERUS would have led to overtreatment in 14.0% while all patients who had an MRI scan would have been overtreated. Overall, in patients having preoperative imaging, the risk of overtreatment was 44.0% in our series.

Our results show that the surgeon’s judgment and experience in a high-volume centre combined with the results of preoperative biopsies were sensitive and accurate in determining which tumour was appropriate for TEM resection. Although hampered by limitations (discussed below), to our knowledge our study is the first to illustrate the accuracy of surgeon staging for benign lesions when combined with negative biopsies, avoiding unnecessary tests, stress and potentially radical surgery. With the growing use of TEM and other platforms such as transanal minimally invasive surgery, we believe these procedures should be performed only in high-volume centres, as experience plays an important role in adequate surgical planning.

Limitations

Our study is limited by significant bias selection. Every tumour included in the study was evaluated by 1 of the colorectal surgeons at our institution before being cleared for TEM. This might explain why the vast majority of tumours did not have any preoperative imaging. If the tumour looked benign on the basis of its appearance and consistency as well as the results of the biopsies, the surgeons deemed it reasonable to proceed with TEM without any preoperative imaging. If there was any doubt about the presence of invasive carcinoma, repeat biopsies were taken and preoperative imaging was contemplated. Another major limitation of this study is that the study was underpowered because of the small number of patients with preoperative imaging. Very few patients underwent preoperative imaging and all of this imaging was performed outside our tertiary care centre before the referral. Hence, imaging was performed with different modalities and variable operator experience. This limits the conclusions we can draw from the imaging group.

Conclusion

On the basis of our results, we conclude that rectal villous tumours without invasive carcinoma on biopsies and without malignant characteristics on appearance and consistency in the judgment of an experienced colorectal surgeon might not benefit from preoperative imaging before the patient undergoes TEM procedures.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association of General Surgeons, Sept. 17–21, Vancouver, B.C.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: F. Letarte, S. Drolet, A.-S. Laliberté, P. Bouchard and A. Bouchard designed the study. F. Letarte and A.-S. Laliberté acquired and analyzed the data, which S. Drolet and A. Bouchard also analyzed. F. Letarte wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication. All authors agreed to be acountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Jahadi MR, Baldwin A., Jr Villous adenomas of the colon and rectum. Am J Surg. 1975;130:729–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 7th ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macciucca M, Casale A, Manganaro L, et al. Rectal villous tumors: MR features and correlation with TRUS in the preoperative evaluation. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:329–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heitman S, Ronksley P, Hilsden R, et al. Prevalence of adenomas and colorectal cancer in average risk individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stulc JP, Petrelli NJ, Herrera L, et al. Colorectal villous and tubulovillous adenomas equal to or greater than four centimeters. Ann Surg. 1988;207:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198801000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pikarsky A, Wexner S, Pinchas L, et al. The use of ultrasound for the correct diagnosis and treatment of rectal villous tumors. Am J Surg. 2000;179:261–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore JS, Cataldo PA, Osler T, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is more effective than traditional transanal excision for resection of rectal masses. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1026–31. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buess G, Hutterer F, Theiss J, et al. A system for transanal endoscopic rectum operation. Chirurgica. 1984;55:677–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Graaf EJ, Burger JW, Van Ijsseldijk AL, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is superior to transanal excision of rectal adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:762–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Graaf EJ, Doornebosch PG, Tetteroo GWM, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery if feasible for adenomas throughout the entire rectum: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1107–32. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a0d06d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langer C, Liersch T, Suss M, et al. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinoma and large adenoma: transanal endoscopic microsurgery (using ultrasound or electrosurgery) compared to conventional local and radical resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:222–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buess G, Kipfmuller K, Ibald R, et al. Clinical results of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:245–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00705331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Graaf EJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2003;239:34–9. doi: 10.1080/00855920310002672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galandiuk S, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, et al. Villous and tubulovillous adenomas of the colon and rectum. A retrospective review, 1964–1985. Am J Surg. 1987;153:41–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor EW, Thompson H, Oates GD, et al. Limitations of biopsy in preoperative assessment of villous papilloma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:259–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02641872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morino M, Allaix ME, Arolfo S, et al. Previous transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal cancer represents a risk factor for an increased abdominoperineal resection rate. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3315–21. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJB, Hop WCJ, et al. The role of ERUS in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumours. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:38–42. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York (NY): Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skandarajah AR, Tjandra JJ. Preoperative loco-regional imaging in rectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:497–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerrieri M, Baldarelli M, Morino M, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery in rectal adenomas: experience of six Italian centres. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakagoe T, Sawai T, Tsuji T, et al. Local rectal tumor resection results: gasless, video-endoscopic transanal excision versus the conventional posterior approach. World J Surg. 2003;27:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehouse PA, Tilney HS, Armitage JN, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: risk factors for local recurrence of benign rectal adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:795–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer C, Liersch T, Suss M, et al. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinoma and large adenoma: transanal endoscopic microsurgery (using ultrasound or electrosurgery) compared to conventional local and radical resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:222–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schäfer H, Baldus SE, Holscher AH. Giant adenomas of the rectum: complete resection by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:533–7. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda Y, Mori M, Abe T, et al. Indications for performing transanal endoscopic microsurgery in rectal cancer patients. Colorectal Dis. 1999;2:13–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2000.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langer C, Liersch T, Suss M, et al. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinoma and large adenoma: transanal endoscopic microsurgery (using ultrasound or electrosurgery) compared to conventional local and radical resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:222–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Graaf EJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;239:34–9. doi: 10.1080/00855920310002672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duek SD, Issa N, Hershko DD, et al. Outcome of transanal endoscopic microsurgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with T2 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:379–84. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellgren A, Sirivongs P, Rothenberger DA, et al. Is local excision adequate therapy for early rectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1064–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02236551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, et al. Rectal cancer: Local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging — a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232:773–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahaye MJ, Engelen SM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Imaging for predicting the risk factors — the circumferential resection margin and nodal disease — of local recurrence in rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26:259–68. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulinna C, Scheidler J, Strauss T, et al. Local staging of rectal cancer: assessment with double-contrast multislice computed tomography and transrectal ultrasound. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;281:123–30. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chun HK, Choi D, Kim MJ, et al. Preoperative staging of rectal cancer: comparison of 3-T high-field MRI and endorectal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1557–62. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gualdi GF, Casciani E, Guadalaxara A, et al. Local staging of rectal cancer with transrectal ultrasound and endorectal magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with histologic findings. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:338–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02258299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, et al. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1384–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]