Abstract

Background and study aims Ileocecal valve (ICV) lesions are challenging to remove endoscopically.

Patients and methods This was a retrospective cohort study, performed at an academic tertiary US hospital. Sessile polyps or flat ICV lesions ≥ 20 mm in size referred for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) were included. Successful resection rates, complication rates and recurrence were compared to lesions ≥ 20 mm in size not located on the ICV.

Results During an 18-year interval, there were 118 ICV lesions ≥ 20 mm with mean size 28.6 mm (44.9 % females; mean age 71.6 years), comprising 9.03 % of all referred polyps. Ninety ICV lesions (76.3 %) were resected endoscopically, compared to 91.3 % of non-ICV lesions ( P < 0.001). However, in the most recent 8 years, successful EMR of ICV lesions increased to 93 %. Conventional adenomas comprised 92.2 % of ICV lesions and 7.8 % were serrated. Delayed hemorrhage and perforation occurred in 3.3 % and 0 % of ICV lesions, respectively, compared to 4.8 % and 0.5 % in the non-ICV group. At first follow-up, rates of residual polyp in the ICV and non-ICV groups were 16.5 % and 13.6 %, respectively ( P = 0.485). At second follow-up residual rates in the ICV and non-ICV lesion groups were 18.6 % and 6.7 %, respectively ( P = .005).

Conclusions Large ICV polyps are a common source of tertiary referrals. Over an 18-year experience, risk of EMR for ICV polyps was numerically lower, and risk of recurrence was numerically higher at first follow and significantly higher at second follow-up compared to non-ICV polyps.

Introduction

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a safe and effective treatment for large ( ≥ 20 mm) colorectal polyps 1 2 , with low procedural morbidity and mortality when compared to surgery 3 4 5 . Lesion size, location, extent, histology, endoscopist expertise, and adherence to post-polypectomy surveillance may limit success of EMR 6 7 8 9 10 11 . Polyps on the ileocecal valve (ICV) pose challenges for EMR because extension into and around the valve orifice and into terminal ileum create difficulty in accessing lesions and is associated with a relatively high risk for recurrence 6 12 13 . We analyzed the success of EMR of large ICV lesions, post-polypectomy complications and recurrence rate compared to the non- ICV polyps. To our knowledge, this is the largest series to specifically address the endoscopic resection of ICV lesions.

Patients and methods

This is a retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database of large colorectal polyps that were resected by a single experienced endoscopist (D.K.R) since 2000 at an academic university hospital. Permission to review the de-identified database was granted by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review board on September 29, 2015. All sessile polyps and flat lesions located at the ICV and ≥ 20 mm in size and referred for EMR were included, with referred non-ICV polyps ≥ 20 mm as a control group. ICV polyps were considered to be lesions that extended onto one or more lips of the ICV orifice. The database includes age, gender, shape, size (as measured by endoscopist estimate with an open snare of known diameter as the reference), location in the colon, endoscopic methods of resection including any closure that was performed, histology, complications and the results of follow-up examinations.

EMRs in the study were performed in 2000 through 2017. Polyp size was measured using a snare of known size. Lesions with a maximum diameter along the colon wall < 20 mm in size (more than a third of all referred lesions) were excluded from the study and data on their resection is not included here.

Lesions were referred for surgery if they had overt evidence of cancer on endoscopic inspection, if portions of the lesions were deemed inaccessible (this perception clearly evolved over the study interval), if polyp features of bulk or fibrosis (sometimes in combination with access issues) prevented resection, or if a resected lesion showed invasive cancer on pathology.

EMRs were performed using high-definition colonoscopes as they became available and a distal attachment on the colonoscope tip (Olympus distal attachment, Olympus Corp, Center Valley, Pennsylvania, United States) was utilized after it became available. The cap was placed so that it extended 3 to 4 mm beyond the colonoscope tip. EMR technique included submucosal injection with saline or 10 % dextrose injection or with hydroxyethyl starch in later years. In all cases indigo carmine or methylene blue was added to the injectate. In most cases, injection was started on the lesion edge closest to the ICV orifice to move lesion away from the valve orifice and improve its accessibility. The entire lesion was resected if possible in a single session during the first colonoscopy. No colonoscopies were performed at our center to “plan” an endoscopic resection. Polyps were resected by piecemeal technique using low-power coagulation current until approximately 2013, and after that using ERBE (Elektromedizin GmbH, Germany) Endocut. If flat residual polyp could not be snared using standard snaring techniques it was ablated with argon plasma coagulation in the early years and later resected using the “snare-cap” technique 14 or avulsion with hot biopsy forceps 15 . Hemostatic clips were applied to the EMR defect after they became available (2006) when the size of the defect and the angle of approach allowed.

Delayed post-resection bleeding was defined as bleeding that occurred after departure from the endoscopy unit and required return to the hospital and either transfusion, hospitalization or repeat colonoscopy. Patients were contacted at least 30 days after EMR by telephone to identify complications.

The first surveillance colonoscopy was scheduled 4 to 6 months after EMR and the second surveillance colonoscopy was 1 year after the first. Most patients were asked to return to our center for follow-up but some who traveled long distances had follow-up by the referring endoscopist and their follow-up examinations are not included. At the first and second surveillance visits, the EMR site was inspected in white light as well as narrow band imaging (NBI) and near focus if available on the instruments (depending on the time period). Cold biopsy specimens of normal-appearing EMR scars without visible residual polyps were obtained on most patients at the first follow-up throughout the study period 16 . If visible polyp was seen at follow-up, it was resected with a snare and submitted to histopathology and the edges of the polypectomy defect were ablated with argon plasma coagulation (APC). After treatment, the mucosal defect from snaring was often closed with hemoclips. A recurrence was counted if either subjective assessment of the site included residual polyp (whether or not confirmed by pathology) or biopsies of the scar showed residual polyp. If the site demonstrated no visible recurrence endoscopically and no biopsies were obtained of the resection site, we considered there was no recurrence at that surveillance examination. Cancer was defined as submucosal invasion of dysplasia.

For purposes of comparing trends over time, we arbitrarily divided the study period into before and after 2010. Chi-square tests were used to compare rates of resection, residual polyp at follow-up, bleeding, and other endpoints between the study and control groups. Two-sample t -tests were used to compare ages and polyp sizes between the groups.

Results

There were 1307 lateral spreading lesions ≥ 20 mm in size, of which 118 lesions in 118 individuals were ICV lesions ( Table 1 ). Patients with ICV polyps included 53 females (44.9 %) with mean age 71.6 years (range 52 – 90) and 65 males (55.1 %) with mean age 67.3 years (range 41 – 87). Patients with ICV polyps were older than patients with non-ICV polyps ( Table 1 ). Mean polyp size was 28.7 mm (range 20 – 70 mm) and median size was 30 mm ( Table 1 ). ICV polyps were significantly smaller than non-ICV polyps ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Comparison of lesions located on the ileocecal valve (ICV) and away from the valve (non-ICV).

| Individuals with ICV polyps (≥ 20 mm) | Individuals with non-ICV polyps (≥ 20 mm) | P value | |

| Total patients | 118 | 1033 | |

| Total polyps | 118 | 1188 | |

| Male | 65 (55.1) | 539 (52.2) | 0.549 |

| Female | 53 (44.9) | 494 (47.8) | |

| Age (mean) at initial procedure | 69.3 | 65.7 | < 0.001 |

| Min age at initial procedure | 41 | 24 | |

| Max age at initial procedure | 90 | 90 | |

| Polyp size | |||

|

28.7 | 32.0 | 0.008 |

|

30 | 30 | |

|

20 | 20 | |

|

70 | 150 | |

| Polyp histology | n = 118 | n = 1188 | 0.153 |

| Tubular adenoma | 44 (37.3) | 469 (39.5) | |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 53 (44.9) | 428 (36.0) | |

| Villous | 4 (3.4) | 32 (2.7) | |

| Hyperplastic | 5 (4.2) | 32 (2.7) | |

| Sessile serrated adenoma | 7 (5.9) | 163 (13.7) | |

| Carcinoma | 1 (0.8) | 25 (2.1) | |

| No biopsy taken or available | 4 (3.4) | 39 (3.3) | |

| Polyps referred to surgery | 18 (15.3) | 97 (8.2) | < 0.001 |

| Conservative management | 10 (8.5) | 6 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| EMR completed | 90 (76.3) | 1085 (91.3) | < 0.001 |

ICV, ileocecal valve; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection

Following endoscopic assessment, 18 ICV lesions were referred for surgical resection ( Table 1 ). The most common reason was lesion extension into the ileum (the lesion was still visible when the TI was actually intubated). One lesion had endoscopic evidence of cancer which was confirmed by endoscopic biopsy. Conservative management (no resection and observation if appropriate) was recommended for 10 individuals because of advanced age and comorbidities. The fraction of patients recommended to have conservative therapy for ICV polyps was higher than for non-ICV polyps ( P < 0.001).

Ninety ICV polyps underwent EMR and were sent to histopathology. Pathology revealed tubular adenoma (n = 37), tubulovillous adenoma (n = 42), villous adenoma (n = 4), hyperplastic (n = 2), and sessile serrated polyp (n = 5). Excluding the 10 patients who had treatment deferred because of age and comorbidities, the rate of endoscopic resection prior to 2010 was 64 % (21 of 33 cases). For ICV polyps referred in 2010 and after the rate of endoscopic resection was 92 % (69 of 75 cases; P < 0.001). Sixty-four post EMR sites on the ICV (71 %) had hemostatic clips placed for prevention of delayed bleeding, compared to 63 % of sites not involving the ICV. Three subjects with ICV polyps had delayed post-polypectomy hemorrhage and were managed endoscopically. There were no perforations in the ICV group and 5 (0.5 %) in the non-ICV group.

Seventy-nine individuals with ICV lesions underwent first surveillance colonoscopy at our center (mean interval 7.7 months, range 2.3 – 75 months). There was no difference between the groups with or without first follow-up surveillance at our center (gender, P = 0.11; age, P = 0.94; polyp size, P = 0.46).There were 13 patients with recurrent polyp (10 with visible residual polyp verified by pathology and 3 with visible polyp not verified by pathology), for a recurrence rate at first follow-up of 16.5 %. Twelve of 71 ICV adenomas (16.9 %) had residual disease at first follow-up and one of eight (12.5 %) non-adenomatous polyps had residual disease. One patient was sent for surgical rescue based on a recurrence identified at first follow-up. In the control group of non-ICV polyps 881 patients underwent first follow-up at our center. There were 120 sites with residual polyp at first follow-up, including 89 with a visible recurrence verified by pathology, 19 with a visible recurrence not verified by pathology, and 12 with no visible recurrence but positive biopsies for residual polyp. The overall rate of residual polyp at first follow-up in the non-ICV polyps was 13.6 % and not different from the ICV polyps ( P = 0.485) ( Table 2 ). To our knowledge, none of the patients treated for recurrence at the first or second follow-up had complications from treatment.

Table 2. Post-polypectomy biopsy results at first and second surveillance visits.

| Post-polypectomy site biopsy | ICV group | Control group | P value |

| 1st surveillance visit | 79 | 881 | |

| Residual polyp(s)/positive scar biopsy | 13 (16.5 %) | 120 (13.6 %) | 0.485 |

| Polypectomy scar not biopsied | 5 | 130 | |

| 2nd surveillance visit | 43 | 504 | |

| Residual/recurrent polyp(s) | 8 (18.6 %) | 34 (6.7 %) | 0.005 |

| Polypectomy scar not biopsied | 10 | 186 |

ICV, ileocecal valve

Forty-three individuals with ICV lesions completed a second surveillance colonoscopy at our center (mean interval after first follow up 15.7 months, range 4 – 60 months after the first follow-up). There were five post-polypectomy sites with visible residual polyp confirmed by histology, and three sites with visible residual polyp not verified by pathology. The recurrence rate at the second follow-up for ICV polyps was 18.6 %, including 18.4 % for 38 adenomas with second follow-up. One patient with residual ICV polyp at the second follow-up was sent for surgical rescue. There were 506 patients who had non-ICV polyps who underwent a second surveillance colonoscopy at our center. Of them, 34 had residual polyp, including 25 with visible polyp verified by pathology, six that had visible polyp not verified by pathology, and three who had normal appearing scars but biopsies that showed residual polyp. The rate of residual polyp at second follow-up in the non-ICV polyps was 6.7 %, which was lower than the rate at second follow-up in the ICV polyps ( P = 0.005) ( Table 2 ).

Discussion

Video 1 A flat polyp on the right edge of the valve. Note the injection is performed on the aspect of the lesion closest to the valve orifice. The cap is used to force the distal lip of the valve down and turn the lesion on face. The cap is also used at some points to enable snaring and resection 14 . Submucosal fat is exposed in some areas, a common occurrence in ascending colon lesions and a consistent occurrence in valve lesions.

To our knowledge, this series of 118 large ICV polyps is the largest series to specifically address the issue of ICV polyp resection by EMR. We found that ICV polyps represented nearly 9 % of all large polyps referred for EMR at our center. This high percentage of ICV lesions likely reflects the challenges of approaching lesions that are technically difficult to access because of the shape of the ICV and its orifice and the challenge of exposing lesions that extend proximally from the ICV orifice toward the medial wall of the cecum or extend laterally into the valley between the ICV and the lateral cecal wall. Consistent with this suggestion, ICV lesions were significantly smaller in size than non-ICV lesions. The resectability rate of large ICV polyps was lower than non-ICV polyps in our experience, but increased to comparable rates in the last 8 years. This likely reflects increased experience with EMR in general and use of tools such as the colonoscope distal attachment to expose polyp in the valve orifice and extending from the valve onto the medial wall of the cecum. Further, although the rate of resectability was lower for ICV polyps for the entire time period, absolute rates of successful EMR were still high. Given the lower cost and risk of EMR compared to surgical therapy 3 17 18 19 , EMR is a viable option for resection of ICV polyps.

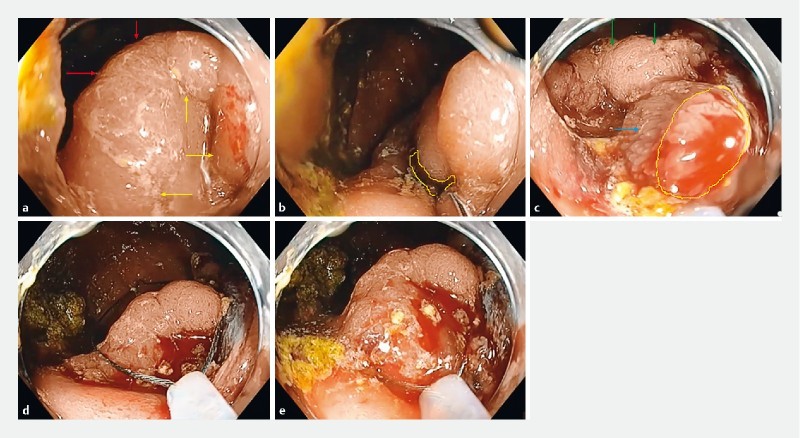

In our experience, keys to effective resection of ICV polyps include: (1) use of a high-definition colonoscope; (2) use of a cap on the distal end of the scope; (3) inclusion of a contrast agent in the injection fluid; and (4) initiating injection at the margin of the polyp with the valve orifice ( Fig. 1 , Video 1 ). High-definition imaging is critical to differentiate polyp tissue from villi and small bowel mucosa, which often has a tubular pattern near the transition between small bowel and colonic mucosa. The short cap on the end of the colonoscope permits the distal lip of the ICV to be tipped down, exposing the ICV orifice and all surfaces of the lips of the ICV to en face examination and therapy ( Fig. 1a ) 20 . When polyp extends from the proximal lip onto the medial wall of the cecum, the cap can be used to force the entire valve down, exposing the mucosa between the ICV and the appendiceal orifice to examination and treatment ( Video 1 ). Inclusion of a contrast agent in the injectate also helps to differentiate the polyp margin from small bowel mucosa, which as noted can be challenging in the transition zone between small bowel and colonic mucosa. Finally, initiating injection at the lesion margin adjacent to the valve orifice can push the polyp away from the orifice, improving exposure of the polyp ( Fig. 1b , Video 1 ). Some caution is needed in applying this rule to lesions on the proximal lip of the orifice, because injection at the lesion edge on the orifice may push the lesion away from the colonoscope tip into the valley between the ICV and appendiceal orifice. The endoscopist must anticipate the effects of injection, and control the injection volume so that it improves rather than impedes exposure of the lesion.

Fig. 1.

Resection of a flat (Paris 2a) lateral spreading tumor extending around 60 % of the valve circumference. There is considerable fecal material in the cecum. a The valve is turned en face to the colonoscope tip by the pressure of the cap on the valve lip at the bottom of the photo. There is fecal debris in the cap on the left. Yellow arrows designate the edge of the lesion closest to the valve orifice. Red arrows designate the visible edge of the lesion that is furthest from the orifice. b The yellow line outlines the ileal orifice. At the lower right the needle is ready for insertion along the polyp edges nearest the orifice, in order to push the lesion away from the orifice. c The yellow line encircles a polyp edge on the distal lip of the valve on the margin with ileal mucosa that is enclosed in a polypectomy snare. The blue arrow points to small bowel villi that are enclosed in the snare. The green arrows point to as yet unresected polyp on the proximal lip of the valve. d,e Resection continues on the proximal edge. Note how the cap forces the distal lip of the valve down, exposing polyp on the proximal lip for resection.

We found that recurrence rates for polyps on the ICV were similar to non-ICV polyps at first follow-up, but higher at second follow-up compared to non-ICV polyps. Some may question our definition of residual polyp, because it included lesions where the endoscopist identified residual polyp but the pathologist was unable to verify this when the residual polyp was resected. In the ICV group, only 43 patients underwent a second examination at our center, and three of eight recurrences were not verified by pathology. The rationale for using this definition is that areas of residual polyp at follow-up are often tiny (just a few millimeters in diameter) and often very flat. We routinely employed low-power coagulation current with a snare to resect areas of residual polyp. This approach was designed to deliver enough coagulation effect to destroy residual polyp tissue that was typically located on a scar. Thus, the treatment could be reasonably expected to sometimes thermally destroy the residual polyp tissue in the attempt at resection, and our anecdotal impression is that this was often the case. Given this, this definition of recurrence may be the most appropriate definition of recurrence. However, we acknowledge that if recurrence definition is confined to lesions with histologically documented residual polyp, we would not have found a higher recurrence rate at second follow-up. Our data suggest that lesions involving the ICV orifice should undergo two follow-ups.

A previous study of 53 large ICV lesions had results mostly similar to ours 12 . Thus, EMR was achieved in 93.6 % and 81.1 % ultimately avoided surgery. The recurrence rate at first follow-up was 17.5 %, the delayed bleeding rate was 6.4 %, and there were no perforations. Unlike in our study, the recurrence rate at the second follow-up was only one in 22 (4.5 %). Thus, the previous study did not show an unexpectedly high rate of recurrence at follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its large size, and that we prospectively accumulated the data. Our methods for collecting cases make us confident that all referred sessile and flat lesions ≥ 20 mm in size were included. We expect the main observations here to have good generalizability. Limitations of the study include the retrospective design and incomplete follow-up of all lesions at our center. Also, although the total number of ICV lesions is larger than any previously reported study specifically addressing this issue, the total number of lesions that had two follow-ups is small. With regard to patients “lost” to follow-up, our center is a referral center for EMR for patients within and outside of Indiana. Lower rates of follow-up should not be perceived as a weakness of EMR based on our study, because many patients had planned follow-up elsewhere due to distance from our center and are not included in follow-up results reported here. We consider the number of follow-ups at our center sufficiently large to make observations about recurrence rates likely to be accurate. In addition, the span of the study is long, and improved imaging over the study interval and improved techniques might mean that the overall rate of recurrence for the study period overestimates the rates that would be expected with expert EMR technique applied with current colonoscopes and other EMR tools.

Conclusion

In summary, the high number of referred lesions on the ICV indicates the technical challenges of EMR at this location. In a large experience of EMR, resectability of large ICV lesions was numerically lower than non-ICV lesions, but increased with time and endoscopist experience. In recent years, endoscopic resectability rates of ICV and non-ICV polyps were equivalent, indicating that large non-pedunculated ICV lesions are resectable at rates comparable to non-ICV lesions, and should generally be endoscopically resected or referred for endoscopic resection by experts and should not be referred for surgical resection based on location alone. Complication rates were numerically lower for ICV polyps compared to non-ICV polyps. Recurrence rates were numerically higher for ICV compared to non-ICV polyps at first follow-up, and significantly higher at second follow-up. Overall, EMR is an effective and safe approach to resection of large ICV polyps.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant by Scott Schurz of Bloomington, Indiana to the Indiana University Foundation in the name of Douglas K. Rex.

Footnotes

Competing interests Prasanna Ponugoti, Heather Broadley, Jonathan Garcia: no disclosures. Douglas Rex: Consultant: Olympus Corporation, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Aries Pharmaceutical, Braintree Laboratories; Research Support: EndoAid, Olympus Corporation, Medivators, Erbe; Ownership: Satisfai Health.

References

- 1.Tutticci N, Klein A, Sonson R et al. Endoscopic resection of subtotal or completely circumferential laterally spreading colonic adenomas: technique, caveats, and outcomes. Endoscopy. 2016;48:465–471. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-101854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan C, Senore C, Radaelli F et al. Full-spectrum (FUSE) versus standard forward-viewing colonoscopy in an organised colorectal cancer screening programme. Gut. 2017;66:1949–1955. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlenstiel G, Hourigan L F, Brown G et al. Actual endoscopic versus predicted surgical mortality for treatment of advanced mucosal neoplasia of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raju G S, Lum P J, Ross W A et al. Outcome of EMR as an alternative to surgery in patients with complex colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee E Y, Bourke M J. EMR should be the first-line treatment for large laterally spreading colorectal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Yague A, Kaltenbach T, Raju G et al. Advanced endoscopic resection of colorectal lesions. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:459–477. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutter M D, Nickerson C, Rees C J et al. Risk factors for adverse events related to polypectomy in the English Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Endoscopy. 2014;46:90–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tate D J, Desomer L, Klein A et al. Adenoma recurrence after piecemeal colonic EMR is predictable: the Sydney EMR recurrence tool. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:647–INF. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aziz Aadam A, Wani S, Kahi C et al. Physician assessment and management of complex colon polyps: a multicenter video-based survey study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1312–1324. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau J M et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:842–851. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman D A, Rex D K, Winawer S J et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–857. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanda K S, Tutticci N, Burgess N G et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading lesions involving the ileocecal valve: technique, risk factors for failure, and outcomes. Endoscopy. 2015;47:710–718. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss A, Williams S J, Hourigan L F et al. Long-term adenoma recurrence following wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection (WF-EMR) for advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia is infrequent: results and risk factors in 1000 cases from the Australian Colonic EMR (ACE) study. Gut. 2015;64:57–65. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsa N, Rex D K. Short cap technique to complete EMR of very flat colorectal laterally spreading tumors. VideoGIE. 2017;2:229–230. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrawes S, Haber G. Avulsion: a novel technique to achieve complete resection of difficult colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:167–168. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khashab M, Eid E, Rusche M et al. Incidence and predictors of “late” recurrences after endoscopic piecemeal resection of large sessile adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayanna M, Burgess N G, Singh R et al. Cost analysis of endoscopic mucosal resection vs surgery for large laterally spreading colorectal lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:271–278 e271-272. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keswani R N, Law R, Ciolino J D et al. Adverse events after surgery for benign colon polyps are common and associated with increased length of stay and costs. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:296–3030. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peery A F, Shaheen N J, Cools K S et al. Morbidity and mortality after surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:243–2.5E244. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conio M, Blanchi S, Filiberti R et al. Cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection of large polyps involving the ileocecal valve. Endoscopy. 2010;42:677–680. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]