Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the antimicrobial efficiency of piperitenone epoxide (PEO) – a principal component of various aromatic plants’ essential oil – in combination with various antibiotics against 28 strains of Staphylococcus aureus and 10 strains of Escherichia coli isolated from clinical samples. Mentha spicata’s essential oil, initially collected by hydrodistillation, was then subjected to flush column chromatography affording PEO of high purity. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of PEO alone and in combination with various concentrations of antibiotics were assessed using the microdilution method. The combined action was estimated calculating the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index from checkerboard assays. Our results showed that the average minimum inhibitory concentration (mg/l) of PEO alone against E. coli was 512 ± 364.7 μg/ml, which was significantly higher than 172.8 ± 180.7 μg/ml observed for S. aureus. From checkerboard assays, FIC values below the 0.5 index, indicating synergy, were observed for 59% of the drugs tested. Twelve percent of FIC index values were between 0.5 and 1, indicating additive effects, while 21% were indifferent. According to our results, PEO could be a promising antimicrobial compound when combined with specific antibiotics and deserves further study.

Keywords: piperitenone epoxide, antibiotics, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, minimum inhibitory concentration, fractional inhibitory concentration, fractional inhibitory concentration index

Introduction

The increase in antibiotic resistant strains is a global public health concern in the continuous fight against pathogens. Owing to the lack of efficient drugs, it is estimated that 400,000 infections and more than 25,000 deaths occur annually in the European Union alone (ECDC/EMEA, 2009; Bush et al., 2011), creating also a significant economic impact of over €1.5 billion (Smith and Coast, 2013; Prestinaci et al., 2015). As alternatives to antibiotics, many researchers have explored the use of essential oils (EOs) or other bioactive compounds occurring naturally as secondary metabolites of aromatic and medicinal plants (Hammer et al., 1999; Lambert et al., 2001; Bakkali et al., 2008; Alexopoulos et al., 2011; Fournomiti et al., 2015; Saviuc et al., 2015). EOs are oily liquids rich in aromatic compounds, which are extracted from plant material mainly by steam- or hydrodistillation (Asbahani et al., 2015). Owing to their antiseptic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, anticancer, antioxidant, and analgesic properties (Adorjan and Buchbauer, 2010), they have a long history of use in traditional medicine (Raut and Karuppayil, 2014), cosmetology (Aburjai and Natsheh, 2003), crop protection (Dayan et al., 2009), and also in food preparation and preservation (Burt, 2004). The mechanism of antibacterial action of EOs is attributed either or collectively to the disruption of the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and various diverse effects upon cellular metabolism (Lambert et al., 2001; Ultee et al., 2002; Di Pasqua et al., 2007).

However, despite their traditional use and proven biological properties, the use of EOs as antibacterial agents is constrained from limitations or disadvantages in their efficiency, variation in composition, toxicity, usability, bacterial resistance, and lack of knowledge of their mode of action (Bakkali et al., 2008; Baser and Buchbauer, 2015; Owen and Laird, 2018). In this context, as an alternative strategy, the combined action of existing antibiotics with complex phytochemicals or with their individual components was suggested from various investigators (Hemaiswarya et al., 2008; Wagner and Ulrich-Merzenich, 2009; Hyldgaard et al., 2012; Langeveld et al., 2014; Magi et al., 2015; Owen and Laird, 2018). This strategy combines the multidrug resistant modifier action of phytochemicals with the selectivity of antibiotics to overcome the intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms of bacteria with promising results toward their efficacy and commercialization viability (Hemaiswarya et al., 2008; Owen and Laird, 2018).

In 2001, Hu et al. (2001) successfully inhibited β-lactamase in β-lactamase-producing Staphylococcus aureus combining epigallocatechin-gallate and ampicillin/sulbactam, while Sakagami et al. (2005) inhibited methicillin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin enterococci via the combination of α-mangostin with vancomycin. Since then, various studies have proven the successfulness of such combinations, with some of them demonstrating a remarkable up to 256-fold reduction in the antibiotic concentration (Owen and Laird, 2018). Similar results from the combined use of phytochemicals have also been obtained in various food models as well (Honório et al., 2015).

Of the well-known aromatic and medicinal plants, mints of the Lamiaceae family include more than 20 species and natural hybrids. Their properties were discovered in ancient times, and today, several mint species and their EOs are exploited at various fields in medicine (Pagonopoulou et al., 2012; Koutroumanidou et al., 2013; Baser and Buchbauer, 2015). Their properties are related to the volatile compounds that constitute their EO, of which pulegone, carvone, and menthol have been extensively studied (Sivropoulou et al., 1995; Tassou et al., 1995, 2000; Tsai et al., 2013).

Piperitenone and its epoxide (PEO) and peroxide (PPO) derivatives are among the not so well-studied components occurring in EOs of various plants. These p-menthane type monoterpenes are natural constituents of the chemotypes of various plant species as Calamintha nepeta and Calamintha glandulosa (Kokkalou and Stefanou, 1990; Cook et al., 2007), Satureja parvifolia (Zygadlo et al., 1993), Hyptis capitata (Thoppil and Jose, 1995), Tagetes patula (Tamut et al., 2017), Rosmarinus officinalis (Gachkar et al., 2007), Eucalyptus olida, Eucalyptus dives (Gilles et al., 2010), and Micromeria congesta (Herken et al., 2012). However, it is in the Lamiaceae family and particularly in mint genus where PPO and PEO are among the main monoterpene components. Geographical origin, cultivation techniques, and even isolation methods are among the factors that influence plants’ EOs composition (Ciobanu et al., 2002; Teles et al., 2013) resulting most often in PPO and PEO being isolated from various Mentha spp. as minor ingredients and in percentages close to 1% (Duarte et al., 2005; Soković et al., 2009). In other mint species, however, these compounds are abundant and consisting a high percentage (from 40 to 85.4%) of their volatiles (Tomei et al., 2003; Esmaeili et al., 2006; Gachkar et al., 2007; Benayad et al., 2012). Mentha spp. rich in PPO/PEO have been reported from China (Zhao et al., 2013), Israel (Segev et al., 2012), Jordan (Abu-Al-Futuh et al., 2000), Lithuania (Venskutonis, 1996), and Greece (Kokkalou and Stefanou, 1990).

Epoxides, in general, are active compounds, and various studies have shown that, in mammals, they are able to react with nucleophilic groups in proteins (Guengerich, 2003) or acting as haptens, eliciting significant reactions to the skin (Nilsson et al., 2005). Sousa et al. (2009) reported an antinociceptive activity of PPO in mice and suggest that this effect is probably an indirect anti-inflammatory reaction.

Despite the fact that there are numerous reports concerning the antimicrobial activities of EOs against pathogens (Lang and Buchbauer, 2012), there are relatively limited studies exploiting the combined action of EOs and antibiotics (Langeveld et al., 2014; Owen and Laird, 2018). Among them, there is not, to our knowledge, a similar study concerning the combined action of PEO and antibiotics against clinical pathogens. Therefore, the aim of the present work was to assess the antimicrobial efficiency of PEO in combination with various antibiotics against S. aureus and Escherichia coli strains isolated from clinical samples.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

Twenty-eight clinical strains of S. aureus and 10 clinical strains of E. coli were used in the study. These strains were donated over time from “Metaxa” Anticancer Hospital and are now part of the frozen strain collection of the Laboratory of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Hygiene. Strains have been identified via VITEK 2 Compact (BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and kept frozen in Tryptone Soya Broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) enriched with 30% glycerol until use. S. aureus strains were non-methicillin-resistant, and E. coli were non-extended spectrum β-lactamase producers as revealed by latex agglutination test (OxoidTM Ltd., United Kingdom) and Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) double disk method (Gupta et al., 2013). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC® 25923TM and E. coli ATCC® 25922TM were used as reference strains. Before assays, all strains were incubated in the appropriate conditions to ensure optimal growth and purity. In the present study, no human or animal subjects were involved or any recorded data are used or maintained, and therefore, no ethics approval is required.

Isolation and Characterization of Piperitenone Epoxide

Isolation and structural characterization of PEO followed the procedure as we previously described (Kimbaris et al., 2017). Briefly, aerial parts of full flowered plants of M. spicata were collected during July of 2018 from a wild-growing population in Sparti (South of Greece, Peloponisos). Plant material was air dried and cut into small pieces, and 500 g was subjected to hydrodistillation for 3 h, using a Clevenger type apparatus. The collected EO (1.8 ml/100 g dry wt) was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtrated, and finally stored in sterile screw capped dark bottles at −22°C until use. Gas chromatographic–mass spectroscopic analysis (GC-MS) revealed, as expected, piperitone epoxide (23.2%) and PEO (50.9%) as the major ingredients. Part of the extracted crude EO (4 g) was fractioned by column chromatography on silica gel and eluted with a gradient of solvents of increasing polarity (pentane+diethyl). The resulted yellowish oil, identified as (+)-PEO (1.6 g, mixture of cis and trans diastereoisomers), was found in high purity (∼99.0%) according to GC-MS analysis. Structural determination was carried out by GC-MS and 1H- and 13C-NMR analysis, and the results were in agreement to previously reported (Kimbaris et al., 2017).

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the various antibiotics was determined using commercially available 96-well microplate panels (Sensititre®, Trek Diagnostic System), preloaded with antibiotics (Table 1) following the method recommended by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2012). Assays were performed in Muller–Hinton broth (MHB) (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). In each well, 100 μl of MHB was added along with 20 μl of a diluted bacterial suspension in NaCl 0.85% to give a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml. Wells without bacteria were used as negative controls. Plates were incubated for 16–24 h at 37°C, and growth was assessed after addition of tetrazolium dye [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide or MTT] (Sigma-Ardrich®) and further incubated for 60 min. The MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration without visible growth. Three independent assays were performed.

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of antibiotics used for Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in the assay.

| Antibiotic | S. aureus (test range in μg/ml) | Dilutions∗ | E. coli (test range in μg/ml) | Dilutions∗ |

| Amikacin | nt | – | 64–0.5 | 7 |

| Ampicillin | 16–0.06 | 8 | 32–0.5 | 6 |

| Cefepime | nt | – | 32–0.5 | 6 |

| Ceftazidime | nt | – | 32–8 | 2 |

| Ceftriaxone | 64–0.03 | 11 | 64–0.06 | 10 |

| Levofloxacin | 32–0.06 | 9 | 8–0.008 | 10 |

| Linezolid | 8–0.5 | 4 | nt | – |

| Meropenem | 16–0.12 | 7 | 16–0.06 | 8 |

| Minocycline | 8–0.25 | 6 | 16–0.5 | 5 |

| Penicillin | 8–0.06 | 7 | nt | – |

| Tigecycline | 16–0.008 | 11 | 16–0.008 | 11 |

| Vancomycin | 32–0.12 | 8 | nt | – |

∗Number of twofold dilutions starting from the largest concentration, nt, not tested.

The MIC of PEO against pathogens was determined also by the broth microdilution method. A bacterial suspension was prepared in MHB from fresh overnight stock culture bearing a final concentration of 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml or 0.5 McFarland turbidity units estimated using a dedicated densitometer (DensiCHEKTM Plus, Biomerieux). In each well, 100 μl of MHB was added supplemented with dimethyl sulfoxide at a final concentration of 2% (v/v) to ensure oil solubility. In the first column of wells, 50 μl of PEO was added (1,024 μg/ml) and serially diluted horizontally to a final concentration of 0.25 μg/ml. An aliquot of 50 μl from bacterial suspension was added to each well. Plates were covered and incubated at 37°C for 16–24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration with no visible growth.

Checkerboard Assay

To study the combined action of antibiotics and PEO, five Sensititre® plates were used for every strain with each one of the plates containing a different concentration of PEO. The concentrations of PEO used were selected on the basis of MIC values previously determined (four twofold dilutions starting at 32 mg/l (i.e., 32, 16, 8, and 4 μg/ml). Higher concentrations of PEO could be effective also but unworthy for clinical exploitation. MHB used in combined experiments was supplemented with dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Ardrich®) at a final concentration of 2% (v/v). Incubation conditions and interpretation of results were similar to the ones already described. The combined action of the antibiotics and PEO was expressed in terms of fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (FICI) equal to the sum of FICs for each drug. The FIC is defined as the MIC of each substance or drug used in combination divided by the MIC of the substance or drug used alone based on the following equation (Doern, 2014):

| (1) |

The results were considered as a synergistic effect if the FICI of the combination is ≤0.5, additive when 0.5 < FICI < 1, indifferent when 1 < FICI ≤ 2, and antagonistic for FICI > 2 (EUCAST, 2000). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of the mean MIC values of PEO and antibiotics against S. aureus and E. coli was performed with the Mann–Whitney non-parametric procedure at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of PEO and Antibiotics

In our study, overall MIC values of PEO ranged between 32 and 1,024 μg/ml (Table 2). The average MIC (μg/ml) of PEO against the 10 E. coli strains was 512.2 ± 364.7 μg/ml, which is significantly higher (Mann–Whitney p < 0.05) than 172.8 ± 180.7 μg/ml observed for the 28 S. aureus strains.

TABLE 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (μg/ml) of piperitenone epoxide (PEO) and antibiotics against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

|

Minimum inhibitory concentration (μg/ml)∗ | |||||||||||||

| Strain | PEO | AMK | AMP | FEP | CAZ | CRO | LVX | LZD | MEM | MIN | PEN | TGC | VAN |

| E. coli 1 | 256 | 4 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 0.06 | nt | 2 | 2 | nt | 0.5 | nt |

| E. coli 2 | 512 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 0.12 | nt | 1 | 4 | nt | 0.5 | nt |

| E. coli 3 | 1024 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 2 | nt | 2 | 16 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| E. coli 4 | 512 | 4 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 0.06 | nt | 2 | 2 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| E. coli 5 | 512 | 4 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 64 | 2 | nt | 4 | 16 | nt | 0.12 | nt |

| E. coli 6 | 128 | 4 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 32 | 8 | nt | 2 | 16 | nt | 0.12 | nt |

| E. coli 7 | 128 | 4 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 64 | 8 | nt | 4 | 16 | nt | 0.12 | nt |

| E. coli 8 | 512 | 4 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 0.06 | nt | 2 | 2 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| E. coli 9 | 1024 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 2 | nt | 2 | 16 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| E. coli 10 | 512 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 0.06 | nt | 2 | 2 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| E. coli 25922 | 512 | 1 | 4 | <0.5 | <8 | 0.05 | 0.06 | nt | 0.06 | 2 | nt | 0.25 | nt |

| S. aureus 1 | 256 | nt | 32 | nt | nt | 8 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 2 | 64 | nt | 32 | nt | nt | 16 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 3 | 128 | nt | 0.25 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 |

| S. aureus 4 | 128 | nt | 2 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 5 | 64 | nt | 32 | nt | nt | 16 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 |

| S. aureus 6 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 7 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 16 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 |

| S. aureus 8 | 256 | nt | 0.12 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 9 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 10 | 64 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 11 | 256 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 16 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 12 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 13 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 14 | 64 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 15 | 256 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 16 | 256 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 17 | 256 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 |

| S. aureus 18 | 32 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 16 | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 19 | 256 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 20 | 64 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 21 | 32 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 22 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 16 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 |

| S. aureus 23 | 32 | nt | 0.25 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 4 |

| S. aureus 24 | 32 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 25 | 1024 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 16 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2 |

| S. aureus 26 | 256 | nt | 0.12 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.5 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 2 |

| S. aureus 27 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 |

| S. aureus 28 | 128 | nt | 16 | nt | nt | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 25923 | 64 | nt | 0.25 | nt | nt | 4 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

∗Mean values of three replicates, nt, not tested. Piperitenone epoxide (PEO), Amikacin (AMK), Ampicillin (AMP), Cefepime (FEP), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Ceftriaxone (CRO), Levofloxacin (LVX), Linezolid (LZD), Meropenem (MEM), Minocycline (MIN), Penicillin (PEN), Tigecycline (TGC), Vancomycin (VAN).

Based on the ecological cutoff values presented by EUCAST (2019), E. coli strains were proven to be multiresistant in almost all antibiotics. All 10 strains were resistant to cefepime (FEP), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftriaxone (CRO), and meropenem (MEM) and sensitive to amikacin (AMK) and tigecycline (TGC). The resistance percentage of E. coli isolates to the rest of antibiotics ranged from 50 to 70%.

Similarly, an increased resistance to several antibiotics was observed for S. aureus isolates particularly in ampicillin (82.1%), linezolid (71.4%), and minocycline (82.1%). Resistance ranged from 10 to 25% for the rest of the antibiotics, while none of the S. aureus isolates was resistant to tigecycline and only one to vancomycin (3.6%). Resistance to penicillin (>1 μg/ml) was recorded in three strains. E. coli and S. aureus reference strains were constantly exhibiting sensitivity to the majority of the drugs.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration of PEO and Antibiotics

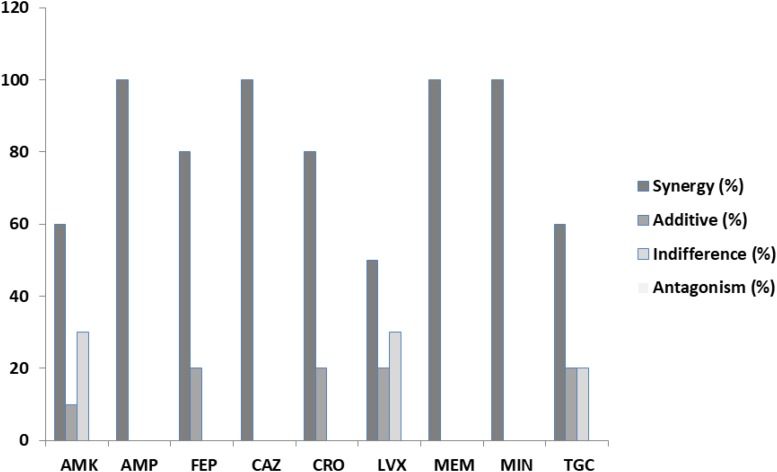

In our results, out of the 90 assays (240 with the replications) to determine the FICs from the combination of antibiotics and PEO on clinical isolates of E. coli, synergy, according to EUCAST (2000), was detected in 73 or 81.1% (Table 3). A complete synergistic effect was recorded in the case of amikacin/PEO, ampicillin/PEO, ceftazidime/PEO, meropenem/PEO, and minocycline/PEO, whereas 50–80% synergism was observed for the rest of the antibiotics when combined with PEO. Additive effects were exhibited by 10% of the FICIs and indifferent by 5.5%. No antagonistic interactions were recorded during the E. coli experiments (Figure 1).

TABLE 3.

Mean values and interpretations according to EUCAST (2000) of fractional inhibitory concentration indexes (FICI) for piperitenone epoxide (PEO) and antibiotics against 10 Escherichia coli strains.

| Strain | AMK | AMP | FEP | CAZ | CRO | LVX | MEM | MIN | TGC |

| E. coli 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 1.50 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.49 |

| E. coli 2 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.49 |

| E. coli 3 | 1.50 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 1.06 |

| E. coli 4 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 1.06 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| E. coli 5 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.56 |

| E. coli 6 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 1.50 |

| E. coli 7 | 1.50 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| E. coli 8 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.37 |

| E. coli 9 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| E. coli 10 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 1.06 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.30 |

| E. coli 25922 | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| ∗Synergy (%) | 60 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 80 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 60 |

| ∗Additive (%) | 10 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| ∗Indifference (%) | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| ∗Antagonism (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

∗Reference strain not included. Amikacin (AMK), Ampicillin (AMP), Cefepime (FEP), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Ceftriaxone (CRO), Levofloxacin (LVX), Meropenem (MEM), Minocycline (MIN), Tigecycline (TGC).

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure of piperitenone epoxide (PEO).

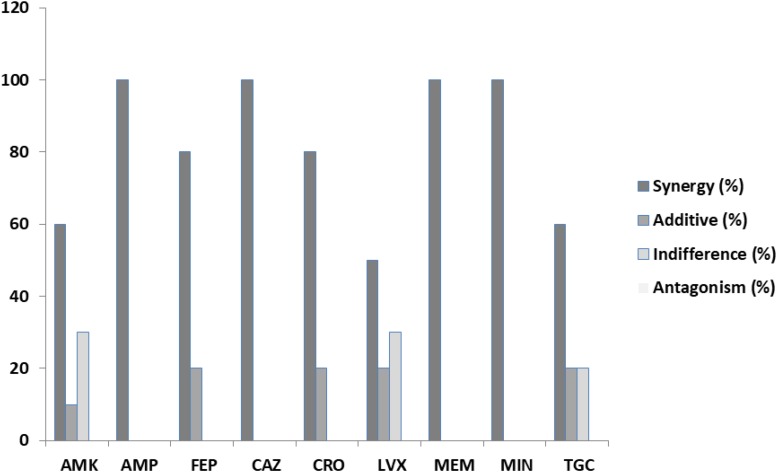

Among the S. aureus assays (Table 4), synergism was observed for all antibiotics but in variable percentages. Specifically, 67.86% of the ceftriaxone/PEO, levofloxacin/PEO, and linezolid/PEO combinations exhibited synergism (FICI ≤ 0.5). Similarly, synergism was observed in 60.71% of the vancomycin/PEO combination, 57.14% of ampicillin/PEO, 53.57% of penicillin/PEO, 42.86% minocycline/PEO, 35.71% of meropenem/PEO, and finally 3.57% of tigecycline/PEO. The frequency of additive effects ranged between 0 and 21.43%. Indifference was recorded in all combinations of antibiotics/PEO (ranged from 10.71 to 67.86% per antibiotic), and finally, antagonistic effects were recorded in six out the nine combinations of antibiotics/PEO and in ranges from 10.71% and up to 25% of the assays (Figures 2, 3).

TABLE 4.

Mean values of fractional inhibitory concentration indexes (FICI) for piperitenone epoxide and antibiotics against 28 Staphylococcus aureus strains.

| Strain | AMP | CRO | LVX | LZD | MEM | MIN | PEN | TGC | VAN |

| S. aureus 1 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 3.00 | 1.50 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 2 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 2.50 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 2.00 | 0.75 |

| S. aureus 3 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 0.37 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 4 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 2.00 | 1.50 |

| S. aureus 5 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 3.00 | 0.63 | 3.00 | 1.25 |

| S. aureus 6 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 7 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 3.00 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 8 | 1.25 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 2.00 | 0.63 |

| S. aureus 9 | 0.38 | 2.00 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 10 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.49 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 0.75 |

| S. aureus 11 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 12 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 1.48 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 3.08 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 13 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 0.50 | 2.58 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 14 | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 1.48 | 0.56 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 0.75 |

| S. aureus 15 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 2.33 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 16 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 1.25 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 2.00 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 17 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 1.25 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 18 | 3.00 | 0.56 | 1.02 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 1.25 | 4.50 | 2.00 | 0.75 |

| S. aureus 19 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 20 | 3.00 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 1.24 | 1.50 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 0.75 |

| S. aureus 21 | 1.25 | 1.13 | 3.00 | 1.13 | 1.48 | 1.25 | 1.13 | 2.00 | 1.50 |

| S. aureus 22 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 1.25 | 0.50 | 1.50 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 23 | 3.00 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 1.25 | 2.48 | 3.00 | 9.00 | 5.17 | 1.25 |

| S. aureus 24 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 2.25 | 2.13 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| S. aureus 25 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 0.31 |

| S. aureus 26 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 5.00 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| S. aureus 27 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 1.48 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 28 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 25923 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| ∗Synergy(%) | 57.14 | 67.86 | 67.86 | 67.86 | 35.71 | 42.86 | 53.57 | 3.57 | 60.71 |

| ∗Additive(%) | 17.86 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 17.86 | 0 | 10.71 | 10.71 | 10.71 | 21.43 |

| ∗Indifference(%) | 14.29 | 17.86 | 7.14 | 14.29 | 39.29 | 35.71 | 10.71 | 67.86 | 17.86 |

| ∗Antagonism (%) | 10.71 | 0 | 10.71 | 0 | 25 | 10.71 | 25 | 17.86 | 0 |

∗Reference strain not included. Ampicillin (AMP), Ceftriaxone (CRO), Levofloxacin (LVX), Linezolid (LZD), Meropenem (MEM), Minocycline (MIN), Penicillin (PEN), Tigecycline (TGC), Vancomycin (VAN).

FIGURE 2.

Percentages of synergy, additive, indifference, and antagonistic interactions between nine commercial antibiotics and piperitenone epoxide against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from checkerboard assays.

FIGURE 3.

Percentages of synergy, additive, indifference, and antagonistic interactions between nine commercial antibiotics and piperitenone epoxide against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from checkerboard assays.

Discussion

Recent data suggest that the estimated burden of infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria is substantial and has increased over the last years forcing toward comprehensive European and global action plans (Cassini et al., 2019). Based on this increase in antibiotic resistance, products of natural origin as the EOs alone or in combination with other agents could be a promising alternative (Lang and Buchbauer, 2012; Langeveld et al., 2014). EOs are secondary metabolites of aromatic and medicinal plants and play an important role in their proliferation and defense (Baser and Buchbauer, 2015). Most of them are terpene and terpenoid mixtures with a lipophilic nature. However, since EOs are complex mixtures with variable and unsteady composition (Thoppil and Jose, 1995; Teles et al., 2013), they are hardly useful for medicinal use (Owen and Laird, 2018).

Piperitenone and piperitone are among the main components of various EOs isolated from aromatic and medicinal plants, particularly from Mentha sp., which, according to Mahboubi and Haghi (2008), belongs to piperitone/piperitenone type of EOs. From the limited available literature, it is known that both compounds have proven antimicrobial activities against Mucor rouxii (Bakkali et al., 2008), S. aureus (Mahboubi and Haghi, 2008), and Aspergillus flavus (Cárdenas-Ortega et al., 2005). Early studies have shown that PEO increased the antimicrobial activity of furazolidone and nitrofurantoin (Shahverdi et al., 2004). Their mode of action is mostly associated with their lipophilic nature, the accumulation in membranes, and the sensitization of the phospholipidic bi-layer of the cell membrane causing an increase in permeability and leakage of various vital constituents (Conner, 1993; Moreira et al., 2005). However, both epoxides have not been investigated for their synergism in combination with antibiotics.

The European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) has proposed (EUCAST, 2000) a classification of the FICI occurring from a combination of antibiotics according to which any FICI ≤ 0.5 denotes synergy, additive when 0.5 < FICI ≤ 1, indifference when 1 < FICI < 2, and antagonism when FICI ≥ 2. Another interpretation for checkerboard assays was proposed by Odds (2003), arguing about the reproducibility problems arising from the use of this methodology in comparison to others less prone to errors (Lewis et al., 2002) but also less popular to microbiologists. According to Odds (2003), a synergy could be defined if FICI was ≤0.5 and antagonism when FICI > 4. For FICI values between 0.5 and 4, “no interaction” should be stated. According to that author, such a conservative interpretation would be helpful for comparison purposes of the data published in the antimicrobial field. To deal with the reproducibility problems of the multiple checkerboard assays for the estimation of MIC and FIC, Fratini et al. (2017) proposed a modification in which both MIC and FIC are estimated in the same microplate. According to those authors, similar errors occur for the two estimations, and therefore, a synergistic effect is detected when FICI value < 1, a cumulative effect when FICI value = 1, an indifferent effect when 1 < FICI ≤ 2, and an antagonistic effect when FICI value > 2 (Fratini et al., 2017). In E. coli experiments which exhibited synergism, the mean reduction in the effective drug doses were 4-fold for amikacin, ceftazidime, minocycline and tigecycline, 8-fold for ampicillin and ceftriaxone, 16-fold for cefepime and meropenem, and up to 133-fold reduction for levofloxacin. The corresponding mean reductions for the drugs assayed in S. aureus strains were 8-fold for ampicillin, ceftriaxone, meropenem, and penicillin; 4-fold for linezolid, minocycline, tigecycline, and vancomycin; while there was a 66-fold mean reduction in the effective dose for levofloxacin. It is clear from our data that the use of PEO in combination with the various drugs gave some positive results about the synergistic effects, and despite the initial and relatively high MIC values of this compound, it finally reduced considerably the effective doses of the drugs even in the case of E. coli which, as a Gram(−) microorganism, is more resistant to the EOs antibacterial action (Lang and Buchbauer, 2012).

The mechanism of action of PEO is not known, and this is also the case for any EO or their component. However, we can speculate on the site of action since there are relevant scientific evidence about molecules highly analogous to the PEO like carvacrol, thymol, and p-cymene. Among others, Ultee et al. (2002), Gill and Holley (2006), and Di Pasqua et al. (2007) have studied the way carvacrol, a key compound in oregano EO, acts on the bacterial cell. They proposed that the membrane disruption and destabilization leading to leakage of cell ions, fluidization of membrane lipids, and the reduction in the proton motive force is the primary target for those molecules. Additional modes of action, following the disruption of the membrane with potential intracellular targets as the inhibition of ATPase activity, has been also proposed for thymol and p-cymene (Lambert et al., 2001; Ultee et al., 2002; Trombetta et al., 2005; Di Pasqua et al., 2010). In a similar way, we can speculate that the destabilization of the membrane by PEO results in a more efficient diffusion of drugs in the membrane or in the cell, thus exhibiting a higher activity being at a lower dose. However, in our study, decisive data like the minimum bactericidal concentration or time of kill were not estimated, and no molecular approaches were involved; therefore, no specific assumptions about the bactericidal effects can be drawn (Wagner and Ulrich-Merzenich, 2009). Consequently, it is apparent that more research is needed to demonstrate the feasibility of use for the combined action of drugs and EOs constituents.

Conclusion

The multidrug-resistant microorganisms represent an increasingly widespread hazard. Essential oils could be an effective alternative to drugs in human and veterinary medicine. Particularly, various EOs compounds as the PEO, due to their promising synergistic or additive action, could be employed to reduce the effective drug dose against common pathogens, thus limiting the overuse of antibiotics or reducing their resistance.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AK, SP, and IM were responsible for the isolation and chemical characterization of PEO from EOs. CT, OP, and ES concerned with susceptibility testing. CV, MF, and CB performed the checkerboard assays. VP was responsible for the strains. AA and EB conceived the study and actively involved in all of the above.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abu-Al-Futuh I. M., Abdelmageed O. H., Jamil R. M., Avato P. (2000). A piperitenone oxide chemotype of Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. growing wild in Jordan. J. Essent. Oil Res. 12 530–532. 10.1080/10412905.2000.9712151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aburjai T., Natsheh F. M. (2003). Plants used in cosmetics. Phytother. Res. 17 987–1000. 10.1002/ptr.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adorjan B., Buchbauer G. (2010). Biological properties of essential oils: an updated review. Flavour Fragr. J. 25 407–426. 10.1002/ffj.2024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos A., Kimbaris A., Plessas S., Mantzourani I., Theodoridou I., Stavropoulou E., et al. (2011). Antibacterial activities of essential oils from eight Greek aromatic plants against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Anaerobe 17 399–402. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbahani A. E., Miladi K., Badri W., Sala M., Addi E. H. A., Casabianca H., et al. (2015). Essential oils: from extraction to encapsulation. Int. J. Pharm. 483 220–243. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali F., Averbeck S., Averbeck D., Idaomar M. (2008). Biological effects of essential oils–a review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46 446–475. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baser K. H. C., Buchbauer G. (2015). Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- Benayad N., Ebrahim W., Hakiki A., Mosaddak M. (2012). Chemical characterization and insecticidal evaluation of the essential oil of Mentha suaveolens L. and Mentha pulegium L. growing in Morocco. Sci. Stud. Res. 13 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Burt S. (2004). Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 94 223–253. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Courvalin P., Dantas G., Davies J., Eisenstein B., Huovinen P., et al. (2011). Tackling antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:894. 10.1038/nrmicro2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Ortega N. C., Zavala-Sánchez M. A., Aguirre-Rivera J. R., Pérez-González C., Pérez-Gutiérrez S. (2005). Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oil of Chrysactinia mexicana Gray. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 4347–4349. 10.1021/jf040372h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassini A., Högberg L. D., Plachouras D., Quattrocchi A., Hoxha A., Simonsen G. S., et al. (2019). Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19 56–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-30604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu Y., Peleah E., Pisova M., Zueva A. (2002). Comparison of essential oil composition of Mentha arvenses L. from different geographical regions. Koryo, Terupen oyobi Seiyu Kagaku ni kansuru Toronkai Koen Yoshishu 46:91. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical, and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2012). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 22nd Informational Supplement (Vol 32). Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Conner E. (1993). “Naturally occurring compounds,”Antimicrobials in foods, 2nd Edn Ed. Michael Davidson P., Alfred Larry Branen Y. (New York NY: Marcel Dekker Inc.) 441 468. [Google Scholar]

- Cook C. M., Lanaras T., Kokkini S. (2007). Essential oils of two Calamintha glandulosa (Req.) Bentham chemotypes in a wild population from Zakynthos. Greece. J. Essent. Oil Res. 19 534–539. 10.1080/10412905.2007.9699324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan F. E., Cantrell C. L., Duke S. O. (2009). Natural products in crop protection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17 4022–4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasqua R., Betts G., Hoskins N., Edwards M., Ercolini D., Mauriello G. (2007). Membrane toxicity of antimicrobial compounds from essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55 4863–4870. 10.1021/jf0636465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasqua R., Mamone G., Ferranti P., Ercolini D., Mauriello G. (2010). Changes in the proteome of Salmonella enterica serovar Thompson as stress adaptation to sublethal concentrations of thymol. Proteomics 10 1040–1049. 10.1002/pmic.200900568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doern C. D. (2014). When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52 4124–4128. 10.1128/JCM.01121-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M. C. T., Figueira G. M., Sartoratto A., Rehder V. L. G., Delarmelina C. (2005). Anti-Candida activity of Brazilian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 97 305–311. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC/EMEA (2009). The Bacterial Challenge, Time to React: a Call to Narrow the Gap Between Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the Development of New Antibacterial Agents. Stockholm: ECDC. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili A., Rustaiyan A., Masoudi S., Nadji K. (2006). Composition of the essential oils of Mentha aquatica L. and Nepeta meyeri Benth. from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 18 263–265. 10.1080/10412905.2006.9699082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2000). EUCAST definitive document E.Def 1.2, May 2000: terminology relating to methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6 503–508. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2019). Antimicrobial Wild Type Distributions of Microorganisms. Available at: https://mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/ (accessed January 18, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Fournomiti M., Kimbaris A., Mantzourani I., Plessas S., Theodoridou I., Papaemmanouil V., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial activity of essential oils of cultivated oregano (Origanum vulgare), sage (Salvia officinalis), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 26:23289. 10.3402/mehd.v26.23289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratini F., Mancini S., Turchi B., Friscia E., Pistelli L., Giusti G., et al. (2017). A novel interpretation of the fractional inhibitory concentration index: the case Origanum vulgare L. and Leptospermum scoparium JR et G. Forst essential oils against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microbiol. Res. 195 11–17. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachkar L., Yadegari D., Rezaei M. B., Taghizadeh M., Astaneh S. A., Rasooli I. (2007). Chemical and biological characteristics of Cuminum cyminum and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils. Food Chem. 102 898–904. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill A., Holley R. (2006). Disruption of Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes and Lactobacillus sakei cellular membranes by plant oil aromatics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 108 1–9. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles M., Zhao J., An M., Agboola S. (2010). Chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of essential oils of three Australian Eucalyptus species. Food Chem. 119 731–737. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.07.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P. (2003). Cytochromes P450, drugs, and diseases. Mol. Interv. 3:194. 10.1124/mi.3.4.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V., Rani H., Singla N., Kaistha N., Chander J. (2013). Determination of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and AmpC production in uropathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli and susceptibility to fosfomycin. J. Lab. Physicians 5 90–93. 10.4103/0974-2727.119849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer K. A., Carson C. F., Riley T. V. (1999). Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and other plant extracts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86 985–990. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemaiswarya S., Kruthiventi A. K., Doble M. (2008). Synergism between natural products and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Phytomedicine 15 639–652. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herken E. N., Celik A., Aslan M., Aydınlık N. (2012). The constituents of essential oil: antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of Micromeria congesta Boiss. & Hausskn. ex Boiss. from East Anatolia. J. Med. Food 15 835–839. 10.1089/jmf.2011.0315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honório V. G., Bezerra J., Souza G. T., Carvalho R. J., Gomes-Neto N. J., Figueiredo R. C. B. Q., et al. (2015). Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus cocktail using the synergies of oregano and rosemary essential oils or carvacrol and 1,8-cineole. Front. Microbiol. 6:1223. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z. Q., Zhao W. H., Hara Y., Shimamura T. (2001). Epigallocatechin gallate synergy with ampicillin/sulbactam against 28 clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48 361–364. 10.1093/jac/48.3.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyldgaard M., Mygind T., Meyer R. L. (2012). Essential oils in food preservation: mode of action, synergies, and interactions with food matrix components. Front. Microbiol. 3:12. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbaris A. C., González-Coloma A., Andrés M. F., Vidali V. P., Polissiou M. G., Santana-Méridas O. (2017). Biocidal compounds from Mentha sp. essential oils and their structure–activity relationships. Chem. Biodivers. 14:e1600270. 10.1002/cbdv.201600270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkalou E., Stefanou E. (1990). The volatile oil of Calamintha nepeta (L.) Savi subsp. glandulosa (Req.) PW Ball, endemic to Greece. Flavour Fragr. J. 5 23–26. 10.1002/ffj.2730050104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koutroumanidou E., Kimbaris A., Kortsaris A., Bezirtzoglou E., Polissiou M., Charalabopoulos K., et al. (2013). Increased seizure latency and decreased severity of pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in mice after essential oil administration. Epilepsy Res. Treat. 2013:532657. 10.1155/2013/532657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert R., Skandamis P. N., Coote P. J., Nychas G. (2001). A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91 453–462. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang G., Buchbauer G. (2012). A review on recent research results (2008–2010) on essential oils as antimicrobials and antifungals. A review. Flavour Fragr. J. 27 13–39. 10.1002/ffj.2082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld W. T., Veldhuizen E. J., Burt S. A. (2014). Synergy between essential oil components and antibiotics: a review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 40 76–94. 10.3109/1040841X.2013.763219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R., Diekema D., Messer S., Pfaller M., Klepser M. (2002). Comparison of Etest, chequerboard dilution and time–kill studies for the detection of synergy or antagonism between antifungal agents tested against Candida species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49 345–351. 10.1093/jac/49.2.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magi G., Marini E., Facinelli B. (2015). Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and carvacrol, and synergy of carvacrol and erythromycin, against clinical, erythromycin-resistant Group A Streptococci. Front. Microbiol. 6:165. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahboubi M., Haghi G. (2008). Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Mentha pulegium L. essential oil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 119 325–327. 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira M., Ponce A., Del Valle C., Roura S. (2005). Inhibitory parameters of essential oils to reduce a foodborne pathogen. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 38 565–570. 10.1016/j.lwt.2004.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A.-M., Bergström M. A., Luthman K., Nilsson J. L. G., Karlberg A.-T. (2005). A conjugated diene identified as a prohapten: contact allergenic activity and chemical reactivity of proposed epoxide metabolites. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18 308–316. 10.1021/tx049758c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds F. C. (2003). Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52 1–1. 10.1093/jac/dkg301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen L., Laird K. (2018). Synchronous application of antibiotics and essential oils: dual mechanisms of action as a potential solution to antibiotic resistance. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 44 414–435. 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1423616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagonopoulou O., Koutroumanidou E., Charalabopoulos K. (2012). Essential oils and neurodegenerative diseases: current data and future perspectives. Curr. Top. Nutraceuticals Res. 10 123–132. 10.1055/a-0758-0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestinaci F., Pezzotti P., Pantosti A. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 109 309–318. 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raut J. S., Karuppayil S. M. (2014). A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Indus. Crops Products 62 250–264. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakagami Y., Iinuma M., Piyasena K. G. N. P., Dharmaratne H. R. W. (2005). Antibacterial activity of α-mangostin against vancomycin resistant Enterococci (VRE) and synergism with antibiotics. Phytomedicine 12 203–208. 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saviuc C.-M., Drumea V., Olariu L., Chifiriuc M.-C., Bezirtzoglou E., Lazar V. (2015). Essential oils with microbicidal and antibiofilm activity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 16 137–151. 10.2174/138920101602150112151549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev D., Nitzan N., Chaimovitsh D., Eshel A., Dudai N. (2012). Chemical and morphological diversity in wild populations of Mentha longifolia in Israel. Chem. Biodivers. 9 577–588. 10.1002/cbdv.201100108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahverdi A., Rafii F., Fazeli M., Jamalifar H. (2004). Enhancement of antimicrobial activity of furazolidone and nitrofurantoin against clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae by piperitone. Int. J. Aromather. 14 77–80. 10.1016/j.ijat.2004.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivropoulou A., Kokkini S., Lanaras T., Arsenakis M. (1995). Antimicrobial activity of mint essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43 2384–2388. 10.1021/jf00057a013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., Coast J. (2013). The true cost of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ 346:f1493. 10.1136/bmj.f1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soković M. D., Vukojević J., Marin P. D., Brkić D. D., Vajs V., Van Griensven L. J. (2009). Chemical composition of essential oilsof thymus and mentha speciesand their antifungal activities. Molecules 14 238–249. 10.3390/molecules14010238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa P. J., da C., Linard C., Azevedo-Batista D., Oliveira A., Coelho-de-Souza A., et al. (2009). Antinociceptive effects of the essential oil of Mentha x villosa leaf and its major constituent piperitenone oxide in mice. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 42 655–659. 10.1590/S0100-879X2009000700010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamut O., Kanwar P. S., Archana P. R., Namita S. P., Kumar P., Verma P. K. (2017). Gas chromatography-Mass spectrometry analysis for profiling of essential oil constituents derived from leaves of French marigold (Tagete patula). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 87 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Tassou C., Drosinos E., Nychas G. (1995). Effects of essential oil from mint (Mentha piperita) on Salmonella enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes in model food systems at 4 and 10 C. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 78 593–600. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassou C., Koutsoumanis K., Nychas G.-J. (2000). Inhibition of Salmonella enteritidis and Staphylococcus aureus in nutrient broth by mint essential oil. Food Res. Int. 33 273–280. 10.1016/s0963-9969(00)00047-48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teles S., Pereira J. A., Santos C. H. B., Menezes R. V., Malheiro R., Lucchese A. M., et al. (2013). Effect of geographical origin on the essential oil content and composition of fresh and dried Mentha×villosa Hudson leaves. Indus. Crops Products 46 1–7. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoppil J., Jose J. (1995). Chemical composition of essential oil in two ethnomedicinal species of Hyptis. Acta Pharm. 45 551–553. [Google Scholar]

- Tomei P. E., Uncini Manganelli R. E., Flamini G., Cioni P. L., Morelli I. (2003). Composition of the essential oil of Mentha microphylla from the gennargentu mountains (Sardinia, Italy). J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 3614–3617. 10.1021/jf026091w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta D., Castelli F., Sarpietro M. G., Venuti V., Cristani M., Daniele C., et al. (2005). Mechanisms of antibacterial action of three monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 2474–2478. 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2474-2478.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.-L., Wu C.-T., Lin T.-F., Lin W.-C., Huang Y.-C., Yang C.-H. (2013). Chemical composition and biological properties of essential oils of two mint species. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 12 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Ultee A., Bennik M., Moezelaar R. (2002). The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 1561–1568. 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1561-1568.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venskutonis P. R. (1996). A chemotype of Mentha longifolia L. from Lithuania rich in piperitenone oxide. J. Essent. Oil Res. 8 91–95. 10.1080/10412905.1996.9700564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Ulrich-Merzenich G. (2009). Synergy research: approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine 16 97–110. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Xu Y. W., Yang G. L., Husaini A. M., Wu W. (2013). Variation of essential oil of Mentha haplocalyx Briq. and Mentha spicata L. from China. Indus. Crops Products 42 251–260. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zygadlo J., Merino E., Maestri D., Guzman C., Espinar L. A. (1993). The essential oils of Satureja odora and s. parvifolia from Argentina. J. Essent. Oil Res 5 549–551. 10.1080/10412905.1993.9698276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.