Abstract

Koalas are an iconic Australian marsupial undergoing precipitous population reduction in South-East Queensland from complex interacting threats. To investigate the causes of death and the interaction of comorbidities with demography in South-East Queensland koalas, a large scale, high-throughput prospective necropsy survey was conducted spanning 2013–2016. During this period, 519 necropsies were conducted in 155 young/subadult koalas, 235 mature, 119 old koalas and 10 of unknown age. Similar numbers of males and females were assessed. Trauma and infectious disease at were the most common single diagnoses. However, comorbidity was frequent, including multicentric infection or infectious disease in combination with trauma or senescence. Female koalas had proportionally more reproductive chlamydiosis compared to males in which the ocular and urinary systems were more commonly affected. Comorbidity and disease were strongly associated with poor body condition, and trauma was associated with good body condition. Animals affected by motor vehicle trauma were often in better body condition than those affected by animal attack, tree fall or other causes of trauma. This study identified a higher frequency of infections and comorbidity then previously reported, confirming the complex nature of interacting threats to the koala population.

Subject terms: Biodiversity, Diseases

Introduction

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is a medium-sized, arboreal folivorous marsupial, with a broad but fragmented distribution associated with Eucalyptus spp. woodlands, its primary food source1. The species is listed nationally as vulnerable in response to population declines in the states of Queensland (QLD) and New South Wales (NSW), and the Australian Capital Territory2,3. Despite being overly abundant in the southern extension of their range, koalas in South-East Queensland (SEQLD) are threatened by the population limiting effects of disease4,5 and habitat clearing for urbanization6, which exposes koalas to trauma from vehicle collisions7 and animal attacks8. Despite investments in medical care and species management, there has been a rapid population decline from 1996 through to 2014, with declines of 80% in the Koala Coast and 54% in Pine Rivers in surveyed Queensland populations9,10.

A recent retrospective epidemiological study using passive surveillance hospital records of koala mortality spanning 17 years determined several major factors drive koala hospital submissions. Vehicle collisions, and chlamydiosis-associated debilitation and infertility were the major causes of mortality and morbidity10,11. However, this study was based on retrospective medical records and necropsies were not conducted in all animals, impeding the detailed interrogation of comorbidity and disease interaction10. Given the complex threats affecting the koala population and the high prevalence of disease and injury found in this retrospective study, a passive surveillance necropsy study was undertaken.

Passive surveillance utilizes medical records or data produced by other health-related activities12, and is an increasingly popular method for wildlife studies due to its cost-effectiveness and the feasibility of collecting information across multiple seasons. In this study, a passive surveillance method was used to recruit koalas for detailed necropsy examination. The purpose of this prospective pathology study was to apply systematic necropsy and data recording methodology to accurately identify causes of mortality and to interrogate the interplay of comorbidities driving terminal koala submissions to hospitals in SEQLD. This is the one of the most extensive pathological studies applied to a declining wild species in Australia, identifying major causes of death, comorbidity trends and permitting the statistical evaluation of variables influencing threats to the species.

Results

Diagnoses of koalas admitted

Necropsies were conducted on 519 koalas. The male-to-female ratio was 1.064 (males: 51.4%, N = 266; females: 48.4%, N = 250; Hermaphrodite: 0.2%, N = 1; sex not recorded in N = 2). The age of koalas differed significantly between sexes (p < 0.001) with more older females compared to males being submitted [old: 61.9% (N = 73) females versus 38.1% (N = 45) males; mature: 45.3% (N = 106) females versus 54.7% (N = 128) males; young: 45.5% (N = 67) females versus 54.5% (N = 58) males; unknown: 40% (N = 4) females and 60% (N = 6) of males].

A total of 29 different diagnoses were made (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 299/519 koalas (57.6%, 95%CI: 53.2–61.9%) were found with co-occurring conditions (referred to as co-morbidities), while 220/519 koalas (43.3%, 95%CI: 38.1–46.8%) were diagnosed with a single condition. The single most common diagnosis in koalas was trauma (42.7%, Table 1) followed by infectious disease (31.8%), while the highest co-morbidity was multicentric infections (32.1%), followed by combinations of infectious disease and trauma (18.4%). Across the 29 diagnoses made on all 519 koalas necropsied, infectious processes were detected in 63.4% (329/519) of cases and trauma in 36.4% (189/519) of cases.

Table 1.

Percentage of diagnoses (N of diagnoses) of the four most common single (N = 220 koalas) and co-occurring (N = 299 koalas) diagnoses made on koalas submitted to wildlife hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland between between April 2013 and July 2016 in South-East Queensland, Australia.

| Type of diagnoses | Single diagnosis | Co-occurring diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious | 31.8% (70) | |

| Infectious (multicentric) | 32.1% (96) | |

| Infectious/other diseases | 7.7% (23) | |

| Infectious/senescence | 15.1% (45) | |

| Infectious/trauma | 18.4% (55) | |

| Trauma | 42.7% (94) | |

| Wasting unknown cause | 7.7% (17) | |

| Neoplasia | 6.4% (14) |

Co-morbidities differed significantly (p < 0.001) between male and female koalas, with 69.6% (174/250; 95%CI: 63.5–75.2%) of females having co-morbidities, but only 46.6% (124/266; 95%CI: 40.5–52.8%) of males. Not surprisingly, co-morbidities differed between age groups, being most common among old koalas (98/118; 83.1%, 95%CI: 75.0–89.3%), followed by mature koalas (123/234; 52.6%, 95%CI: 45.9–51.1%) while still 46.7% of young koalas (72/154; 95%CI: 38.7–54.9%) were diagnosed with more than one disease or health problem. Interestingly, among the mature and young koalas, a larger proportion of females had co-morbidities (p = 0.002 and p = 0.006, respectively), while co-morbidities did not differ between sexes for old koalas (p = 0.128).

Across the 516 koalas that were classified as males or females, there was a significantly larger proportion of females (187/250; 74.8%) affected by infectious diseases (alone or in combination with other conditions) compared to males (141/266; 53.0%) (p < 0.001). However, trauma and poor body condition, termed wasting, were more common in males compared to female animals with 41.4% of males (110/266) affected by trauma (alone or in combination with other conditions) compared to 31.6% females (79/250) (p = 0.023) and 10.5% of males (28/266) suffering from wasting from unknown causes (alone or in combination with other conditions) compared to 1.2% females (3/250) (p < 0.001). No sex differences were observed for neoplasia (females: 20/250; 8%; males: 21/266; 7.9%; p = 1.0)

We then explored for each age group associations between sex and the occurrence of each of the most important diagnoses (infectious, trauma, neoplasia and wasting of unknown cause) occurring alone or in combination with other conditions versus all other diagnoses. While there was no statistical association (p < 0.05) between sex and neoplasia for each of the three age groups, a larger proportion of females across all age groups (compared to males) were diagnosed with infections (young: p < 0.001, mature: p = 0.017, old: p = 0.019) (Table 2). More old males were diagnosed with trauma compared to old females (p = 0.018), but this gender difference was not present for young and mature animals (Table 2). Notably, young and mature males were more likely to have wasting of unknown cause than females (p < 0.001 and p = 0.041, respectively). Wasting of unknown cause did not occur in old animals as poor body condition in this class was assumed to be caused by dental attrition.

Table 2.

Percentage of koalas (N of koalas) of the four most common diagnoses by sex (stratified by age class; N = 509 koalas with age and sex information) for koalas submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016. Koalas may be counted more than once in the diagnoses categories due to co-morbidities.

| Age group | Infectious | Trauma | Neoplasia | Wasting unknown | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Young/Subadult (N = 154) | 67.2% (45/67)* | 35.6% (31/87)* | 46.3% (31/67) | 55.2% (48/87) | 4.5% (3/67) | 5.8% (5/87) | 1.5% (1/67)* | 60.7% (17/87)* |

| Mature (N = 234) | 76.4% (81/106)* | 61.7% (79/128)* | 32.1% (34/106) | 32.8% (42/128) | 9.4% (10/106) | 9.4% (12/128) | 1.9% (2/106)* | 39.3% (11/128)* |

| Old (N = 118) | 80.8% (59/73)* | 60.0% (27/45)* | 17.8% (13/73)* | 37.8% (17/45)* | 8.2% (6/73) | 6.7% (3/45) | ||

*Statistical differences between sex groups at p < 0.05.

Percentage of koalas per sex group within each age class for each diagnosis was calculated as N of koalas per sex and age group for each diagnoses/Total number of koalas per sex and age group.

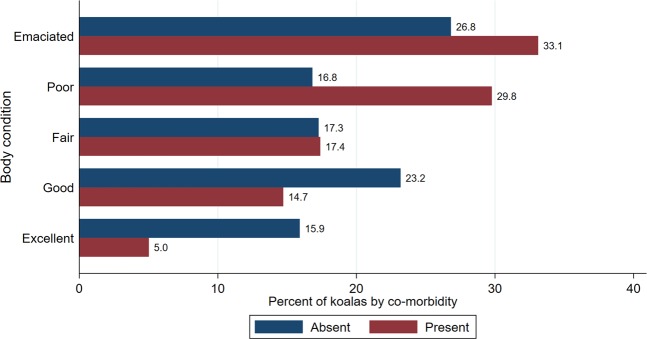

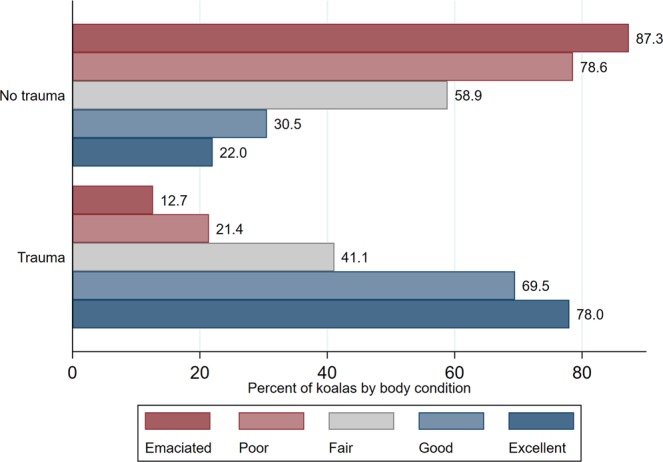

Notably, 30.4% (158/519) of koalas were submitted in emaciated body condition, followed by 24.3% (126/519) koalas in poor, 17.3% (90/519) in fair, 18.3% (95/519) in good and only 9.6% (50/519) in excellent body condition. We also explored the association between body condition and co-morbidities (Fig. 1). Koalas with co-morbidities were more likely to be in detrimental body condition compared to koalas with a single condition (p = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Percentage of koalas by body condition category with co-morbidities absent or present (N = 519). Koalas were submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016.

Infectious disease

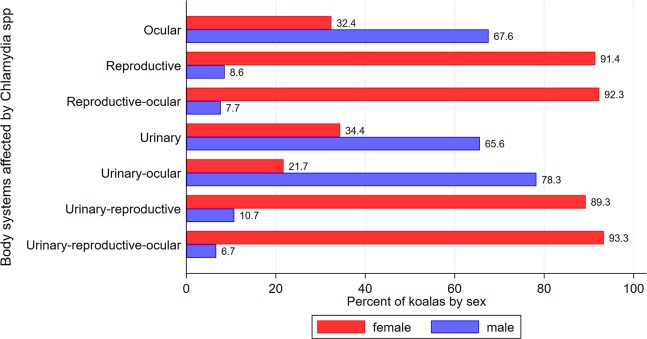

Of the total of 63.4% (329/519) cases with infectious processes (alone or in combination with other conditions), 92.4% (304/329) had hallmark lesions of Chlamydia spp. infection. The percentage of koalas by sex for each body system (alone or in combination with other body systems) affected by Chlamydia spp. are shown in Fig. 2. There were significant differences between female and male koalas in the body system affected (p < 0.001), with the reproductive system alone or in combination with other body systems affecting about 90.0% of female koalas, while ocular, urinary or urinary-ocular infections were observed between 65–78% of male koalas. The distribution of body systems affected by chlamydiosis for each sex strata are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, highlighting that the urinary tract was the most common body system affected in males (52.5% of all Chlamydiosis cases in males) and the urinary-reproductive tracts the most frequent body system affected in females (41.0% of all Chlamydiosis cases in females). Urogenital lesions were diagnosed in 87.8% (267/304) of Chlamydia spp. infections, frequently manifesting as cystitis (65.9%; 176/267). Two representative male koalas with classical urogenital chlamydiosis pathology were tested and were verified positive to C. pecorum via real-time PCR.

Figure 2.

Percentage of koalas by sex with gross lesions compatible with chlamydiosis across body systems (N = 304 koalas with Clamydiaspp. infection). Koalas were submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016.

Urinary disease

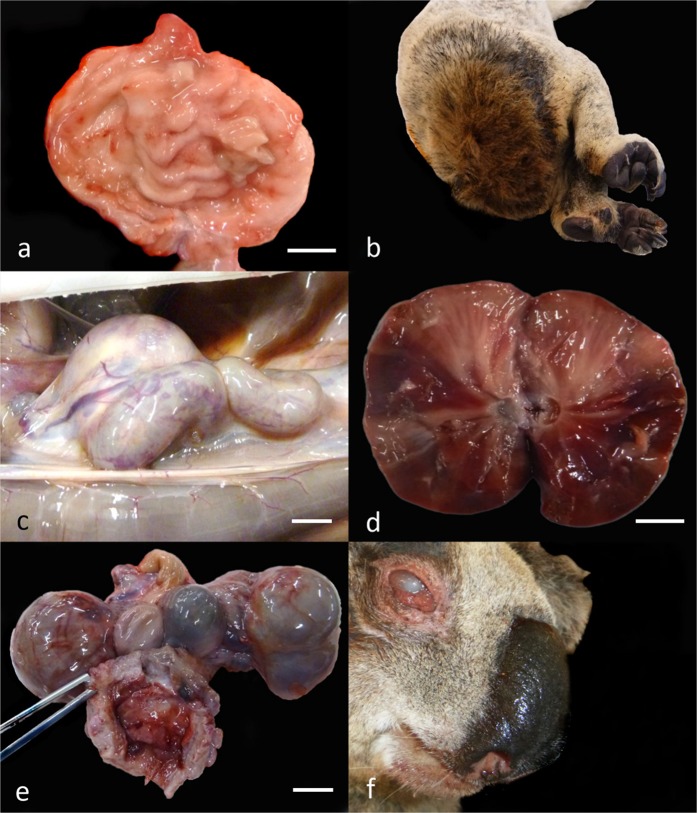

Cystitis was characterized grossly by thickening and firmness of the urinary bladder wall, with mucosal infolding and occasional petechiae (Fig. 3a). Soiling around the common vestibule colloquially referred to as ‘wet bottom’10,13, was common in chronic cases (Fig. 3b). Clinical chlamydial scoring was recovered from medical records for 43 of the 176 cystitis cases, with 58.1% (25/43) severe and 18.6% (8/43) moderate grade. The predominant histological lesion was moderate-to-severe fibrosis accompanied by detrusor muscle hypertrophy, transmural lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, and occasional urothelial ulceration. Chronic cystitis resulted in obstruction of the bladder outlet due fibrosis and myohypertrophy in the bladder wall.

Figure 3.

Gross lesions associated with chlamydiosis in koalas. (a) Urinary bladder with chronic cystitis. (b) ‘Wet bottom’ secondary to chronic cystitis. (c) Hydroureter associated with ascending urinary tract infection. (d) Chronic nephritis. (e) Bilateral bursitis and haemorrhagic cystitis. (e) Chronic conjunctivitis. All bars = 1 cm. Figures (a–d) extracted and modified from Gonzalez-Astudillo, 201910.

Renal complications compatible with chlamydial infection affected 34.8% (106/304) of all koalas and included 9/106 cases of hydronephrosis (Fig. 3c) and 13/106 of renal pyramidal fibrosis from chronic chlamydial pyelonephritis (Fig. 3d). Primary renal disease was also observed without cystitis in 51.8% (43/83) cases. The predominant histological lesion was lymphocytic interstitial nephritis or chronic lymphocytic segmental pyelonephritis. Severe renal disease was infrequent, and included ascending urinary tract infection - UTI (4 cases), end stage kidney disease (4 cases), and pyelonephritis (10 cases). Renal crystal precipitation was observed in 21 cases, mostly morphologically consistent with struvite in 47.6% (10/21) cases, and calcium oxalate in 23.8% cases (5/21).

Reproductive disease

Reproductive lesions consistent with chlamydia infection, predominantly cystic dilation of the ovarian bursa (bursitis) (Fig. 3e), occurred in 66.6% (122/183) female cases with Chlamydia spp. infections at necropsy. In 3.8% (7/183) of these cases, chronic bursitis was found along with gross evidence of salpingitis (acute or chronic). Association of bursitis with fibrotic salpingitis was observed but not consistently recorded. Fluid within the bursa varied from clear and straw-colored, to purulent or hemorrhagic. The bursa was bilaterally compromised in 55.7% (68/122) cases. The main histological feature was replacement of ovarian and fallopian structures with mature collagen, occasionally with lymphocytic infiltration. Infection of other reproductive tract sites co-occurred with bursitis in 22.1% (27/122) of cases, primarily fibrosis or suppurative infection of the uteri. In the male, 64.2% (9/14) of cases of urogenital infections were consistent with chlamydiosis, with cystitis and urethritis most common. Ten of fourteen cases had chronic multifocal prostatitis with intraglandular pustules.

Ocular disease

Ocular lesions consistent with chlamydiosis were diagnosed in 28.9% of koalas (88/304 Chlamydia spp. infections) (Fig. 3f). Chlamydial clinical scoring was recovered for 46.6% (41/88) of cases and frequently was high-grade (85.3%; 35/41; score ≥2). Ocular chlamydiosis was macroscopically a chronic, bilateral (60/88; 68.1%) mucopurulent conjunctivitis/keratoconjunctivitis, with periocular fur matting or alopecia, and palpebral adhesion.

A total of 87.5% (77/88) of ocular disease cases occurred with multisystemic chlamydiosis, and occasionally ‘other diseases’ or dental attrition. Koalas solely with ocular disease rarely had low BC 9.1% (8/88). Animals with ocular disease and low BC typically had a combination of multisystemic comorbidities (67.0%; 59/88).

Trauma

Of the 36.4% (189/519) koalas diagnosed with trauma (alone or in combination with other conditions), based on hospital records, 57.7% (109/189) cases were from motor vehicle collisions, 21.2% (40/189) were from animal attacks (dogs, livestock), 6.9% (13/189) cases corresponded to tree falls, and in 14.3% (27/189) the cause was unknown (Table 3). Acute bone fractures affected 46.0% (87/189), mostly located in the head in 55.1% cases (104/189) or in long bones in 34.5% cases (65/189). Severe hemoabdomen and hemothorax from hepatic and pulmonary lacerations were frequent. Healed bone fractures were infrequent but two cases of proliferative osteophytic periosteal masses compatible with fracture calluses were observed. A total of 10/19 females with evidence or history of carrying pouch or back young perished to trauma caused by motor vehicles.

Table 3.

Percentage of koalas (N of koalas) by trauma type with and without co-morbidities (N = 189 koalas with trauma) for koalas submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016.

| Type of trauma | Percentage koalas (N koalas) |

|---|---|

| Vehicle collisions | |

| Healthy | 56.9% (62) |

| All other diagnosis/trauma | 39.5% (43) |

| Wasting unknown cause/trauma | 3.7% (4) |

| Total | 100% (109) |

| Animal attacks | |

| Healthy | 42.5% (17) |

| All other diagnosis/trauma | 47.5% (19) |

| Wasting unknown cause/trauma | 10.0% (4) |

| Total | 100% (40) |

| Tree falls | |

| Healthy | 23.1% (3) |

| All other diagnosis/trauma | 46.1% (6) |

| Wasting unknown cause/trauma | 30.8% (4) |

| Total | 100% (13) |

| Other causes* | |

| Healthy | 44.4% (12) |

| All other diagnosis/trauma | 48.2% (13) |

| Wasting unknown cause/trauma | 7.4% (2) |

| Total | 100% (27) |

*Trauma by other causes includes categories such as intraspecific trauma, heat stress, and undetermined cause.

In general, koalas with trauma (alone or in combination with other conditions) had better body condition than koalas submitted for other causes than trauma (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of koalas with and without trauma by body condition category (N = 519). Koalas were submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016.

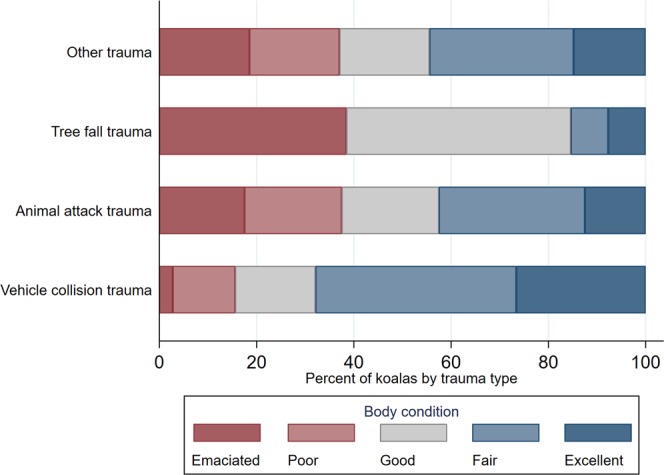

We further explored the relationship between body condition and type of trauma. Koalas with trauma due vehicle collision had significantly better body condition than koalas being affected by animal attack, tree fall, and other trauma causes (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of koalas by trauma type and body condition category (N = 189 koalas with trauma). Koalas were submitted to South-East Queensland hospitals and receiving necropsies at The University of Queensland from 2013 through to 2016.

Neoplastic disease

Neoplasms were detected in 7.9% (41/519) koalas alone or in combination with other conditions. Round cell tumors comprised 58.0% (24/41), including lymphomas (20 cases) and leukemias. Mesenchymal neoplasms affected 39.0% (16/41) of koalas, including cranial14 and costal osteochondromas (7 cases) and primary serosal myxosarcoma15 (2 cases). The least common neoplasms (15%) were epithelial, including colonic and hepatic adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma, and a bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Thirty-nine percent (16/41) neoplasms co-occurred with chlamydiosis, but only 5.0% (2/41) co-occurred with trauma.

Miscellaneous findings

Pulmonary lesions were found in 4.0% (21/519) of koalas including suppurative pneumonias and bronchopneumonias. Focal or interstitial fibrosis indicating chronicity was found in 33.3% (7/21) of koalas with respiratory lesions. Cases with rare or novel pathogens included a Psynchrobacter spp. pleuritis, a pulmonary abscess caused by Mycobacterium abscessus, and a pulmonary phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladosporium spp., all PCR-confirmed.

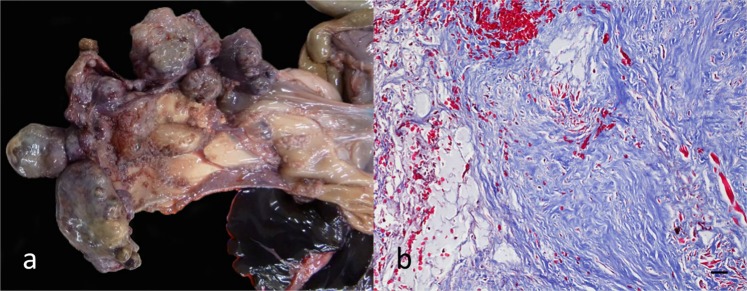

Seven koalas of the 519 koalas presented with multinodular masses in the spleen (Fig. 6a), termed by the authors “koala fibromatosis syndrome”. Nodules were formed by well-differentiated fibrocytes, which effaced and infiltrated the spleen (Fig. 6b) and liver (3 cases). Demographically, sex distribution was similar (4 males, 3 females) and no specific comorbidity pattern was observed. Lympholysis with moderate-to-marked splenic white pulp depletion was present in 9 koalas. Endocrine lesions were rare; the most striking being loss of adrenal chromaffin cells in 4.0% (21/519) of cases.

Figure 6.

Koala fibromatosis syndrome. (a) Fibrotic nodules efface the splenic parenchyma. (b) Histopathology of fibromatosis lesion. Masson’s trichrome stain, 20x magnification. Bar = 30 µm. Figures in this panel extracted from Gonzalez-Astudillo, 201910.

Fate of koalas

For only 173 of the 519 koalas, the fate of koalas was specified in hospital records as being either dead on arrival (N = 63) or being euthanized (N = 110). However, we were able to identify koala fate for 94.6% (N = 491) of koalas based on clinical history specified in the hospital records (N = 351) or deduced at necropsy cases (N = 140) based on the severity of lesions observed for natural death (i.e. massive skull fracture), or by observing barbiturate crystals within tissues for euthanasia. Confounding factors (e.g. evisceration, previous necropsies) hampered the ability to determine koala fate in 28 cases. A total of 80% (393/491) koalas were euthanized, compared to 20.0% (98/491) being dead on arrival or dying during hospitalization. Of the koalas diagnosed with infectious disease (versus all other conditions), 75.6% (297/393) were euthanized and 26.5% (26/98) were dead on arrival (p < 0.001), while for koalas with trauma (versus all other conditions), only 27.0% (106/393) were euthanized, but 80.6% (79/98) were already dead on arrival or died during hospitalization.

Discussion

In the current study, the use of systematic necropsies in passive surveillance increased the sensitivity of disease detection and accurately determined comorbidity patterns compared to a previous analysis using medical records where only brief notes on disease were recorded in some animals. Further, systematic necropsies allowed the characterization of several novel diseases and lower frequency etiologies of infectious, neoplastic or idiopathic disease10,11,15,16.

Pathology data was recorded using a previously developed rapid classification scheme that streamlined data analysis11. The combination of a standardized data recording methodology with systematic necropsies, alongside medical record analysis and ancillary testing, permitted a high (>90%) proportion of conclusive necropsy diagnoses in this study, an excellent rate for wildlife mortality investigations. Other free-ranging wildlife necropsy studies report 46% to 95% rates of determination of primary cause of death10,17–20.

The present study interrogated the interplay of concomitant disease conditions in SEQLD koalas, demonstrating a high rate of comorbidities and reinforcing the complexity and variability of threats to the species. As a single entity trauma was the most common diagnosis in the study, followed by infectious disease. Comorbidities were primarily due to multicentric infections, debilitation, co-occurring trauma and infections. Comorbidities were more common in older animals but still surprisingly prevalent in young koalas, where nearly half had more than one presenting problem. At a population level these conditions would limit breeding potential and increase vulnerability to disease or predation21.

Concomitant conditions in koalas have been investigated previously21–23. A higher proportion of Queensland koalas with loss of BC from comorbidities such as chronic infections or neoplastic disease has been reported than southern states10,13,24. Direct comparison of comorbidity rates with previous studies is complicated due to the different study designs used. Nonetheless, the determination of variation in comorbidity categories between studies and over time assists in establishing a historical pattern for disease interaction in koalas10. Reports from northern koala populations using smaller sample sizes have found comorbidity proportions ranging from 38–60% in QLD13,24 and 19–53% in NSW21,22,25. The proportion of comorbidities found in this study (58%) and our former retrospective epidemiological analysis (38%) is within the documented QLD range. Given the large cohort of koalas assessed and the detailed assessment in the present study, higher accuracy is likely in this analysis.

Historically, trauma has been a major contributor to koala mortality in SEQLD10,11. When koalas inhabit forested land in close proximity to urbanized centers, there is high mortality from trauma, particularly by motor vehicles and dog predation, demonstrating poor adaptability as these threats permeate into their habitat10,26. Koala-motor vehicle collisions have a high fatality rate (>80%)10,27 from a combination of factors22,28, including comminuted fractures21,22 and severe soft tissue trauma causing massive hemorrhage and shock. Dog predation also causes severe soft tissue damage, often leaving pathognomonic bite wound lesions29. Although most animal attacks on koalas in urban areas come from domestic dogs30–32, predation threat could also permeate into protected forests or bushland habitat when carried out by wild dogs and dingoes21,33. Koalas are crepuscular species1 thus responsible pet ownership that restricts dog movements on private land during dawn and dusk may be beneficial10. At younger ages, both male and female koalas are at risk of trauma during post-weaning dispersal30. However, the predominance of mature male koalas in the trauma group could reflect larger home ranges and increased mobility during breeding season34,35. Younger males also tend to disperse more frequently and further than female koalas36. The removal of subadult males by trauma could disrupt population genetic heterogeneity, as these koalas are the primary inter-group dispersers contributing to gene flow36. Notably, in both the medical record and necropsy studies, over half of the animals killed by motor vehicle trauma were healthy. The proportion of healthy animals was also high in animal attack and other trauma causes. Thus, many trauma cases were unnaturally removed from the population predominantly due to anthropogenic factors, potentially causing detrimental impacts on the survival of local populations by reducing healthy breeding stock.

The most frequently reported infectious disease in koalas is chlamydiosis caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae producing conjunctivitis and pneumonia, or the more pathogenic C. pecorum, which causes conjunctivitis, cystitis and reproductive infection resulting in infertility37–39. Classical presentations of clinical chlamydiosis in this study were typically chronic and severe. This reflects the bias of sick wild koalas coming to attention of the public and wildlife rescuers, as well as the clinical management of severely debilitated koalas by euthanasia. In this study morphologic confirmation of typical chlamydial lesions was considered sufficient for diagnosis. Molecular testing for chlamydiosis is of limited value in our context of interrogating drivers of mortality, as subclinical carriers are common and PCR detection and chlamydial load do not correlate with clinical severity40,41. For example, koalas with substantial chronic Chlamydia-associated structural pathology may be PCR-negative and lack chlamydial inclusion bodies, and conversely higher loads can be observed in infected asymptomatic animals then those with clinical disease40–42. A recent study on Chlamydia pecorum in the male koala reproductive system demonstrated 70% of morphologically normal samples and 89% of abnormal samples were qPCR positive43. Typically studies utilizing active surveillance document elevated frequencies of milder chlamydial infections, compared with this study emphasizing bias in sampling methodology44. This dataset will overestimate the proportion of severe end-stage conditions, and underestimate subclinical carriers, but was appropriate for identifying the impact of chlamydiosis as a cause of mortality and infertility10.

A disproportionate number of female koalas of breeding age were diagnosed with chlamydial reproductive disease alone or as a comorbidity10,44–46 compared to males, despite the documented similarity in infection rates across sexes38,47. This reflects the use of ultrasonography to identify permanent female infertility and clinical management by euthanasia10,45,46,48. Additional features influencing female bias in reproductive chlamydiosis include urogenital anatomy, increased rate of opportunistic infections, and lack of detectable sonographic changes in the male unless severely affected44,49,50. However, clinical and subclinical male reproductive tract disease was detected with histopathology. The impact of male urogenital chlamydosis on individual and population health warrants further investigation. Specifically diagnostic testing of hospitalized male koalas and evidenced-based evaluation of the value of treatment of asymptomatic infections should be explored11,44,48.

Cystitis, the main clinical manifestation compatible with chlamydiosis, was found in similar proportion (34%) to other reports21,23,51 but higher compared to that described in an previous study by the authors (27%)10,11. This difference is likely due to the increased sensitivity of necropsies. Notably, a higher proportion of males had ocular and urinary infections alone or as comorbidities. Previous QLD reports questioned the relationship between low BC and ophthalmic chlamydiosis52. In the present study, only 9% of individuals with solely ocular disease had low BC, whilst >60% of koalas with low BC had chronic ocular chlamydiosis associated with comorbidities. Thus, general systemic disease rather than visual impairment causes low BC compromising survivorship52. This study has reinforced that chlamydiosis is still the major impactor on koala mortality and morbidity, with a high rate of multicentric disease and comorbidity.

Koalas live on a highly specialized, nutrient-restricted diet, and have limited visceral fat reserves10,52. As a result, koalas are prone to debilitating and sometimes irreversible BC loss, known as wasting10,11,53–55. Factors causing loss of BC include stressors (prolonged veterinary treatment), or those derived from biotic (social dynamics, resource availability, predation), climatic factors, and dental attrition reducing digestion efficiency56–59. Thus, BC is a relevant parameter to assess in koalas10,11,60 as it may impact successful rehabilitation, population management, or even interact with comorbid states reflecting disease severity. In this study a strong correlation between the presence of disease, comorbidities, type of trauma and body condition was present. Virtually half of diseased koalas (48%) in the present study had poor BC, and animals with poor BC were more likely to have died from non-traumatic causes. In contrast, 95% of the healthy koalas with trauma had a fair to excellent BC. A larger proportion of koalas with low BC were involved in animal attacks, tree fall and other trauma, confirming an elevated risk with increased ground time due to debilitation in increasingly urbanized landscapes21. Conversely, vehicle collisions generally affected animals in good or excellent BC, suggesting these may be active and robust animals moving in search of mates or forage. Notably, male koalas in the young/subadult age class were diagnosed most frequently with idiopathic low BC, exhibiting non-specific clinical histories and lacking necropsy findings. Previous studies reported idiopathic low BC primarily in females, and associated with lymphoid depletion, though this was not consistent in the young males in this study21,23,24,44.

Passive surveillance methodology has limitations including minimal control over data quality, lack of denominator values to estimate disease frequency, and overrepresentation of certain demographic groups or diseases (i.e. incurable, terminal)10,59. For instance, chronic disease and low BC were observed at high frequency, reflecting the biased selection of terminal animals. Conversely, acute infectious disease was underrepresented, reflecting a bias against individuals which could be successfully rehabilitated52. Carcass preservation is often a challenge with wildlife sampling. In koalas, the quality of tissues available for study may have sporadically compromised diagnostic sensitivity due to poor preservation, freezing artefact or eviscerated from previous necropsies, or pap collection for orphaned koalas. In spite of these limitations, utilizing hospital admissions and standardized nomenclature permitted the acquisition of valuable data at the population level in a cost-effective manner, with a high diagnostic success rate. Necropsies proved to be an effective method for the detection of subclinical conditions and identification of comorbidities. In conclusion, management of threats such as trauma, disease, and rapid clearing of koala habitat, need to be tackled in an integrated koala conservation strategy5. This study has quantified major causes of mortality and morbidity and the interaction of comorbidities, reflecting the complex threats acting cumulatively against the SEQLD koala population5–7,61,62.

Materials and Methods

Survey population

Cases for the necropsy survey were sent to the School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Gatton, from three wildlife hospitals (Moggill Koala Rehabilitation Centre, Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Hospital, and Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital) in Queensland, Australia. Koala admissions to these hospitals derived mainly from SEQLD, but also included some regions in NSW in close proximity to the QLD border. Koalas assessed in this study were either found dead, died during hospitalization, or were euthanized. All samples were collected under a Scientific Purposes Permit from the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, Queensland Government (WISP 13247813, generated 07/08/2013), now known as the Department of Environment and Science, and under ethical review of The University of Queensland Animal Welfare Unit (ANRFA/SVS/193/13/EHP).

Necropsies and sample collection

Necropsies were conducted at the School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, between April 2013 and July 2016. The majority of carcasses were frozen at −20 °C due to logistical reasons, and thawed between 0–4 °C for 4–7 days prior to examination. Koalas were identified by ear tags, microchip numbers, or by the hospital accession numbers. Aging was done according to premolar and molar tooth wear designating koalas to an age class (young/subadult, mature, and old)10,56,62. Body condition (BC) score was recorded from 1 through 10 by palpating the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles and ranged from emaciated 1–2, poor 3–4, fair 5–6, good 7–8 and excellent >8 BC60,63.

Histopathology samples were fixed in 10% NBF, sectioned at 4 µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin by routine methods. Special stains performed included: Periodic Acid Schiff’s (PAS), for mucins, mucopolysaccarides and fungal agents, Gram’s for infectious agents, Masson’s Trichrome for collagen and smooth muscle, and Ziehl-Neelsen for acid fast organisms. Ancillary testing included bacterial and fungal culture by routine methods at Veterinary Laboratory Services, The University of Queensland (Gatton, Australia). PCR (panfungal, bacterial) assays were conducted at Pathology West (Sydney, Australia) for the molecular identification of bacteria and fungi. Panfungal PCR targeted fragments of the rDNA gene cluster, specifically, those internally transcribed in spacer region located between the 18S and 28S10,64. The bacterial PCR assay targeted conserved regions U1 and U3 for the 16S rRNA gene using broad range primers10,65. Variable portions within the 16S rRNA gene provide unique signatures of any bacterium. Identification was conducted via sequence analysis of the amplified product10,65.

Clinical disease grading criteria

Chlamydial conjunctivitis and cystitis was subjectively scored by hospitals based on the degree of tissue damage and disease progression following the disease grading criteria of the Moggill Koala Rehabilitation Centre Standard Operating Procedures for conjunctivitis and cystitis treatment 2017 (Supplementary Table 2) as well as previous reports44. Chlamydial bursitis was not clinically-scored as it causes permanent infertility regardless of the degree, with affected females being unable to be returned to the wild, most being euthanased with barbiturates, as per the discretion of the consulting veterinary surgeon under the Veterinary Surgeons Act of Queensland.

Data analysis

Binomial, or also called exact or Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals were calculated for the overall prevalence of observed co-morbidities and for co-morbidities stratified by sex and age66. Exact confidence intervals are more appropriate for small proportions (as for the co-morbidity strata in our study), but as they more conservative, they might be wider than traditional Wald-type intervals67.

Analyses of relationships between the various diagnoses made and demographic information of koalas submitted (sex, age, age class, body condition) were conducted using contingency tables. Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions in the contingency tables68. Data analysis was conducted in STATA 15.0 (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Queensland Government, Department of Environment and Science (formerly the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection), the Moggill Koala Rehabilitation Centre (formerly the Moggill Koala Hospital), Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Hospital and Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital veterinarians and staff for taking an active part in this study. We also thank the UQ Veterinary Laboratory Service, particularly Ben Knoxville and Mick Cobbin for technical assistance. This study was financially supported by a Queensland Government Department of Environment and Heritage Protection KoalaBASE grant no. KRG006 provided to The University of Queensland.

Author contributions

V.G.A. performed sample collection, data mining, and manuscript writing. L.V. developed preliminary diagnostic methodology and undertook necropsy work. L.K. supervised parasite diagnostics. R.L. and A.M. head the veterinary team collecting the koala records. R.A. and J.H. designed the study and provided guidance on data collection and analysis, and contributed to manuscript writing. J.H. conducted the data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors agree to comply with the publication’s requirements for sharing materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-53970-0.

References

- 1.Martin, R. W. & Handasyde, K. The koala: natural history, conservation and management. 132 pgs. UNSW Press (1999).

- 2.Melzer A, Carrick FN, Menkhorst P, Lunney D, St John B. Overview, Critical Assessment, and Conservation Implications of Koala Distribution and Abundance. Conserv. Biol. 2000;14:619–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99383.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAlpine C, et al. Conserving Koalas in the 21st century: synthesising the dynamics of Australia’s Koala populations. Biol. Conserv. 2015;192:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waugh CA, et al. Infection with koala retrovirus subgroup B (KoRV-B), but not KoRV-A, is associated with chlamydial disease in free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:134. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes J, et al. Using integrated population modelling to quantify the implications of multiple threatening processes for a rapidly declining population. Biol. Conserv. 2011;144:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlpine C, et al. The importance of forest area and configuration relative to local habitat factors for conserving forest mammals. Biol. Conserv. 2006;132:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dique D, et al. Koala mortality on roads in south-east Queensland: the koala speed-zone trial. Wildlife Research. 2003;30:419–426. doi: 10.1071/WR02029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAlpine, C. et al. Conserving koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) populations in a fragmented landscape (Noosa Queensland): Research Report. 42 pgs. School of Biological Sciences Publications, The University of Queensland (2004).

- 9.Rhodes, J., Beyer, H., Preece, H. & McAlpine, C. South East Queensland Koala Population Modelling Study. 88 pgs, https://environment.des.qld.gov.au/wildlife/koalas/pdf/seq-koalapopulation-modelling-study.pdf. UniQuest. Brisbane, Australia (2015).

- 10.Gonzalez-Astudillo, V. Analysis of Morbidity and Mortality of Wild Koala in South-East Queensland using Passive Surveillance Data. PhD thesis. 183 pgs. School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland (2018).

- 11.Gonzalez-Astudillo V, Allavena R, McKinnon A, Larkin R, Henning J. Decline causes of Koalas in South East Queensland, Australia: a 17-year retrospective study of mortality and morbidity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42587. doi: 10.1038/srep42587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sergeant, E. & Perkins, N. Epidemiology for Field Veterinarians: An Introduction. 192 pgs. CABI Publishing (2015).

- 13.Weigler BJ, Booth RJ, Osawa R, Carrick FN. Causes of morbidity and mortality in 75 free-ranging and captive koalas in south east Queensland, Australia. Vet. Rec. 1987;121:571–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canfield PJ, Perry R, Brown AS, McKenzie RA. Cranio-facial tumours of mixed cartilage and bone in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) Aust. Vet. J. 1987;64:20–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1987.tb06051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez Astudillo V, Schaffer-White A, Allavena R, Palmieri C. Multiple intra-abdominal serosal myxosarcomas in two Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) J. Comp. Pathol. 2015;152:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Astudillo V, Knott L, Valenza L, Henning J, Allavena R. Parasitism by Ophidascaris robertsi with associated pathology findings in a wild koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Vet. Rec. Case Reports, 2019;0:e000821. doi: 10.1136/vetreccr-2019-000821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shea TJ, Beck CA, Bonde RK, Kochman HI, Odell DK. An Analysis of Manatee Mortality Patterns in Florida, 1976-81. J. Wildl. Manag. 1985;49:1–11. doi: 10.2307/3801830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lair S, Measures LN, Martineau D. Pathologic findings and trends in mortality in the Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) population of the St Lawrence estuary, Quebec, Canada, from 1983 to 2012. Vet. Pathol. 2016;53:22–36. doi: 10.1177/0300985815604726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone WB, Okoniewski JC. Necropsy findings and environmental contaminants in common loons from New York. J. Wildl. Dis. 2001;37:178–184. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-37.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerhold RW, et al. Necropsy findings and arbovirus surveillance in mourning doves from the southeastern United States. J. Wildl. Dis. 2007;43:129–135. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canfield PJ. A mortality survey of free range koalas from the north coast of New South Wales. Aust. Vet. J. 1987;64:325–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1987.tb06059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canfield PJ. A survey of koala road kills in New South Wales. J. Wildl. Dis. 1991;27:657–660. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-27.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obendorf DL. Causes of mortality and morbidity of wild koalas, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss), in Victoria, Australia. J. Wildl. Dis. 1983;19:123–131. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-19.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenzie RA. Observations on diseases of free-living and captive koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) Aust. Vet. J. 1981;57:243–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1981.tb02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Backhouse TC, Bolliger A. Morbidity and mortality in the Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Aust. J. Zool. 1961;9:24–37. doi: 10.1071/ZO9610024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preece ND, et al. A guide for ecologists: Detecting the role of disease in faunal declines and managing population recovery. Biol. Conserv. 2017;2014:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dique, D., Preece, H. & de Villliers, D. Koalas in Pine Rivers Shire: distribution, abundance and management. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Brisbane, Australia (2003).

- 28.Henning J, Hannon C, McKinnon A, Larkin R, Allavena R. The causes and prognoses of different types of fractures in wild koalas submitted to wildlife hospitals. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015;122:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong JK, Blenkinsop B, Sweet J, Wood RE. A comparison of bitemark injuries between fatal wolf and domestic dog attacks. J. Forensic Odontostomatol. 1999;17:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dique D, Thompson J, Preece H, De Villiers D, Carrick FN. Dispersal patterns in a regional koala population in south-east Queensland. Wildlife Research. 2003;30:281–290. doi: 10.1071/WR02043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffith JE, Dhand NK, Krockenberger MB, Higgins DP. A retrospective study of admission trends of koalas to a rehabilitation facility over 30 years. J. Wildl. Dis. 2013;49:18–28. doi: 10.7589/2012-05-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunney D, Gresser S, O’Neill LE, Matthews A, Rhodes J. The impact of fire and dogs on koalas at Port Stephens, New South Wales, using population viability analysis. Pacific Conservation Biology. 2007;13:189–201. doi: 10.1071/PC070189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biosecurity Queensland. Wild dog Canis familliaris. 56 pg. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane, Australia (2016).

- 34.Ellis WAH, Melzer A, Bercovitch FB. Spatiotemporal dynamics of habitat use by koalas: the checkboard model. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2009;63:1181–1188. doi: 10.1007/s00265-009-0761-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellis WAH, Melzer A, Carrick FN, Hasegawa M. Tree use, diet and home range of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) at Blair Athol, central Queensland. Wildlife Research. 2002;29:303–311. doi: 10.1071/WR00111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis WA, Hale PT, Carrick F. Breeding dynamics of koalas in open woodlands. Wildlife Research. 2002;29:19–25. doi: 10.1071/WR01042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins DP, Hemsley S, Canfield PJ. Immuno-histochemical demonstration of the role of chlamydiaceae in renal, uterine and Salpingeal disease of the koala, and demonstration of chlamydiaceae in novel sites. J. Comp. Pathol. 2005;133:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polkinghorne A, Hanger J, Timms P. Recent advances in understanding the biology, epidemiology and control of chlamydial infections in koalas. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;165:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burach F, et al. Chlamydiaceae and Chlamydia-like organisms in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) - organ distribution and histopathological findings. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;172:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nyari S, et al. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection and disease in a free-ranging koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) population. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0190114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patterson JL, et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of Chlamydia infection in island and mainland populations of Victorian koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) J. Wildl. Dis. 2015;51:309–317. doi: 10.7589/2014-07-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hemsley S, Canfield PJ. Histopathological and immunohistochemical investigation of naturally occurring chlamydial conjunctivitis and urogenital inflammation in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) J. Comp. Pathol. 1997;116:273–290. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(97)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmieri C, et al. Chlamydia pecorum infection in the male reproductive system of Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) Vet. Pathol. 2019;56:300–306. doi: 10.1177/0300985818806963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loader, J. An Investigation of the Health of Wild Koala Populations in South-East Queensland. Bachelor of Applied Science thesis, 219 pgs. The University of Queensland (2010).

- 45.Canfield PJ, Oxenford CJ, Love DN, Dickens RK. Pyometra and pyovagina. Aust. Vet. J. 1983;60:337–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1983.tb02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stalder, K., Allen, G. & Krockenberger, M. B. Further investigations into diseases of the koala. In: Wildlife Disease Association Australasian Section. Conference Proceedings. 68 pgs. Wildlife Disease Association (2003).

- 47.Speight KN, et al. Prevalence and pathologic features of Chlamydia pecorum infections in South Australian Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) J. Wildl. Dis. 2016;52:301–306. doi: 10.7589/2015-05-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston SD, et al. Orchitis and epididymitis in Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) infected with Chlamydia pecorum. Vet. Pathol. 2015;52:1254–1257. doi: 10.1177/0300985815570069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obendorf DL. Pathology of the female reproductive tract in the koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss), from Victoria, Australia. J. Wildl. Dis. 1981;17:587–592. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-17.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connolly, J. Emerging diseases of koalas and their medical management. In Proceedings #327: Wildlife in Australia: Healthcare and management, 15–40. Postgraduate Foundation in Veterinary Science. University of Sydney, Australia (1999).

- 51.Canfield PJ. A survey of urinary tract disease in New South Wales koalas. Aust. Vet. J. 1989;66:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1989.tb09758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirst L, Brown AS, Kempster R, Hall JE, Woolcock JB. Keratitis in free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) on Magnetic Island, Townsville. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:424–427. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore BD, Foley WJ. Tree use by koalas in a chemically complex landscape. Nature. 2005;435:488–490. doi: 10.1038/nature03551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gordon G, Brown AS, Pulsford T. A koala (Phascolarctos cinereus Goldfuss) population crash during drought and heatwave conditions in south‐western Queensland. Aust. J. Ecol. 1988;13:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1988.tb00993.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seabrook L, et al. Drought-driven change in wildlife distribution and numbers: a case study of koalas in south west Queensland. Wildlife Research. 2011;38:509–524. doi: 10.1071/Wr11064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis W, et al. Faecal particle size and tooth wear of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Australian Mammalogy. 2014;36:90. doi: 10.1071/am13033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lanyon JM, Sanson GD. Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) dentition and nutrition. II. Implications of toothwear in nutrition. J. Zool. 1986;209:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Booth, R. J., Carrick, F. N. & Addison, P. A. The structure of the koala adrenal gland and the morphological changes associated with stress of disease. In: Biology of the Koala (eds. Lee, K. A., Handasyde, K., & Sanson, G. D.). Surrey Beatty & Sons (1990).

- 59.Davies NA, et al. Physiological stress in koala populations near the arid edge of their distribution. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blanshard, W. & Bodley, K. Koalas. In: Medicine of Australian Mammals (eds. Vogelnest, L. & Woods, R.) Chapter 8, pag. 227–328. CSIRO Publishing, Australia (2008).

- 61.de Oliveira SM, Murray PJ, De Villiers D, Baxter GS. Ecology and movement of urban koalas adjacent to linear infrastructure in coastal south-east Queensland. Australian Mammalogy. 2014;36:45–54. doi: 10.1071/AM12046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gordon G. Estimation of the age of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Marsupialia: Phascolarctidae) from tooth wear and growth. Australian Mammalogy. 1991;14:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson, S., Reid, K., Spittal, S. D. & Romer, L. Koalas. In: Australian Mammals: Biology and Captive Management (ed. S. Jackson). pag. 145–181. CSIRO Publishing (2003).

- 64.Lau A, et al. Development and clinical application of a panfungal PCR assay to detect and identify fungal DNA in tissue specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:380–385. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01862-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Relman, D. A. Universal Bacterial 16S rRNA Amplification and Sequencing. In: Diagnostic Molecular Biology, Principles and Applications (eds Persing, D. H., Smith, T. F., Tenover, F. C. & White, T. J.) pag. 489–495. American Society for Microbiology (1993).

- 66.Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–413. doi: 10.1093/biomet/26.4.404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reed JF., III Better binomial confidence intervals. J. Mod. Appl. St. 2007;6:153–161. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1177992840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agresti AA. Survey of exact inference for contingency Tables. Statistical Science. 1992;7:131–153. doi: 10.1214/ss/1177011454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors agree to comply with the publication’s requirements for sharing materials.