Abstract

Background and Purpose

Women are overrepresented in post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a mental disorder characterised by ineffective inhibition of fear. The use of male animals dominates preclinical studies, which may contribute to a lack of understanding as to why this disparity exists. Thus, the current study explores sex differences in three mouse models of fear inhibition.

Experimental Approach

All experiments tested male and female C57Bl/6J mice. Experiment 1 employed two fear conditioning protocols, in which tones were paired with footshocks of differing intensity (moderate or intense). Fear recall and extinction were tested subsequently. In Experiment 2, safety learning was investigated. Tones were explicitly unpaired with footshocks during safety conditioning. Recall of safety learning was tested 24 hr later. Experiment 3 assessed a model of fear–safety discrimination. Cued stimuli were paired or never paired with footshocks during fear and safety conditioning, respectively. Discrimination between stimuli was assessed 24 hr later.

Key Results

In fear extinction, males, compared to females, responded with greater fear in sessions most proximal to conditioning but subsequently showed a more rapid fear extinction over time. Sex differences were not observed during safety learning. During fear–safety discrimination, both males and females discriminated between stimuli; however, males revealed a greater level of freezing to stimuli.

Conclusion and Implications

The current study provides evidence that sex differences influence fear but not safety‐based behaviour in C57Bl/6J mice. These findings indicate that processing of fear, but not safety, may play a greater role in sex differences observed for PTSD.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed section on The Importance of Sex Differences in Pharmacology Research. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v176.21/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- PTSD

post‐traumatic stress disorder

- CS+

“threat” conditioned stimuli

- CS−

“safe” conditioned stimuli

- ITI

inter‐trial interval

What is already known

Post‐traumatic stress disorder is linked with impaired fear inhibition and overly represented in females.

What this study adds

Female C57Bl/6 mice demonstrate decreased fear recall following conditioning but slower fear extinction.

The acquisition and recall of safety were not overtly influenced by sex.

What is the clinical significance

The processing of fear, but not safety, may be involved in sex differences underlying post‐traumatic stress disorder.

1. INTRODUCTION

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent form of psychiatric illness (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Kilpatrick et al., 2013). PTSD is associated with serious deficits in health and quality of life (Brudey et al., 2015; Ramsawh et al., 2014) as well as significant economic costs to society (Kessler, 2000). Rates of PTSD are disproportionally higher in females, compared to males (Kilpatrick et al., 2013; McLean, Asnaani, Litz, & Hofmann, 2011). Specifically, women are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime (McLean et al., 2011). However, the origin of sex differences in PTSD are not well understood (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Understanding mechanisms underlying such differences is in part impeded by a bias towards the use of males only in preclinical pharmaco‐behavioural studies (Beery & Zucker, 2011; Wald & Wu, 2010). Thus, inclusion of both males and females in preclinical neuro‐pharmacological research is important for the contribution of critical insight into mechanisms underlying sex differences in PTSD.

The inability to effectively inhibit fear is a phenotype of PTSD and is involved in its neurocircuitry and clinical symptoms (Jovanovic, Kazama, Bachevalier, & Davis, 2012; Jovanovic & Norrholm, 2011). Generally, fear inhibition includes three processes: (a) fear extinction refers to learning previous threat cues are no longer dangerous (Milad & Quirk, 2012); (b) safety learning occurs when one learns that environmental stimuli predict safety (Marshall, Acheson, Risbrough, Straus, & Drummond, 2014); and (c) fear–safety discrimination is the process of distinguishing between “threat” and “safety” cues when simultaneously presented (Day, Reed, & Stevenson, 2016). Animal models of fear inhibition have been developed to advance understanding of these phenomena (Bowers & Ressler, 2015; Pollak, Monje, & Lubec, 2010). For example, attempts to model sex differences in PTSD revealed that female rats exhibit fear extinction impairment (Graham & Milad, 2013; Voulo & Parsons, 2017), which is influenced by the oestrous phase (Graham & Milad, 2013; Milad, Igoe, Lebron‐Milad, & Novales, 2009; Zeidan et al., 2011). However, to our knowledge, no study has investigated sex differences in safety learning or fear–safety discrimination in C57Bl/6J mice. The C57Bl/6J is the most commonly used mouse strain in preclinical neuro‐pharmacological studies (Palanza & Parmigiani, 2017). Thus, it is important to investigate whether this strain of mice demonstrate sex differences across fear inhibition‐related processes.

In the current study, we examined whether sex differences exist across several mouse models of fear inhibition. Specifically, we tested male and female C57Bl/6J mice using three experimental models: (a) fear extinction; (b) safety learning; and (c) fear–safety discrimination. In fear extinction (Experiment 1), two fear conditioning paradigms with differing footshock intensities (moderate and intense) were employed to quantify whether sex differences depend on the intensity of the fear conditioning protocol utilised. In safety learning (Experiment 2), males and females were tested to determine their ability to recognise cued safety in an aversive context. Finally, in fear–safety discrimination (Experiment 3), we assessed whether sex differences influence discrimination between threat‐ and safety‐based cues.

2. METHODS

2.1. Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Florey Institute for Neuroscience and Mental Health's Animal Ethics Committee (application number: 17‐058) and conducted in accordance with requirements outlined by the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act and NH&MRC Code of Practice for the Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010) and with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology. Experiments were performed on young adult (~4 months) male and female C57Bl/6JArc (Animal Resource Centre, Canning Vale, WA 6970, Australia; RRID:IMSR_ARC:B6) mice. Following transportation from the breeding facility, male and female mice weighed 20.9–30.4 and 17.1–21.2 g, respectively. Separate cohorts were utilised in each experiment. Mice were randomly allocated within experiments. Mice were group housed (2–4 per cage) in open‐top cages under an inverted 12:12‐hr light : dark cycle (lights off at 0700), with ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Cages contained wood‐shaving‐based bedding (Tapvei Estonia OÜ, Paekna küla, 75408 Harjumaa, Estonia) and tissue paper (Austwide Paper Products Pty Ltd, Dandenong, 3175 Victoria, Australia) as nesting material. Mice were handled for 3 days prior to behavioural testing to decrease anxiety associated with the experimenter (~5 min per handling session per animal). Testing sessions commenced 2 hr following dark‐phase onset, unless otherwise described. One experimenter (male) conducted each session of animal handling and behavioural testing.

2.2. Apparatus and behavioural protocols

A computerised conditioning system (MED Associates, Vermont, USA; RRID:SCR_016928) was utilised in each experiment. The system consists of eight conditioning chambers, each located within a sound attenuated cubicle. Chambers were not illuminated during testing. The flooring of each chamber consisted of stainless steel grids connected to a shock unit, which delivered electrical stimuli (i.e., footshocks). Chambers were fitted with speakers for the presentation of auditory stimuli (i.e., conditioned stimuli). Two experimental contexts were used: (a) square‐shaped chamber with stainless steel flooring underlying shock grid and (b) chamber with curved wall inserts, wood shavings underlying shock grid, and an olfactory contextual change (peppermint tea bag). These were counterbalanced as Contexts A and B in experiments where both contexts were used. Chambers were cleaned with water in between sessions. The delivery of stimuli was controlled by the conditioning system's computer software. Digital recordings were utilised to automatically assess animal movement during testing. Freezing behaviour was defined as lack of movement (other than that required for respiration) for a minimum of 0.5 s. Jumping behaviour was manually scored from videos by one researcher blinded to the sex of the mice. Jumping was counted when all four of the animal's feet left the shock grid. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the experimental protocols utilised in each experiment.

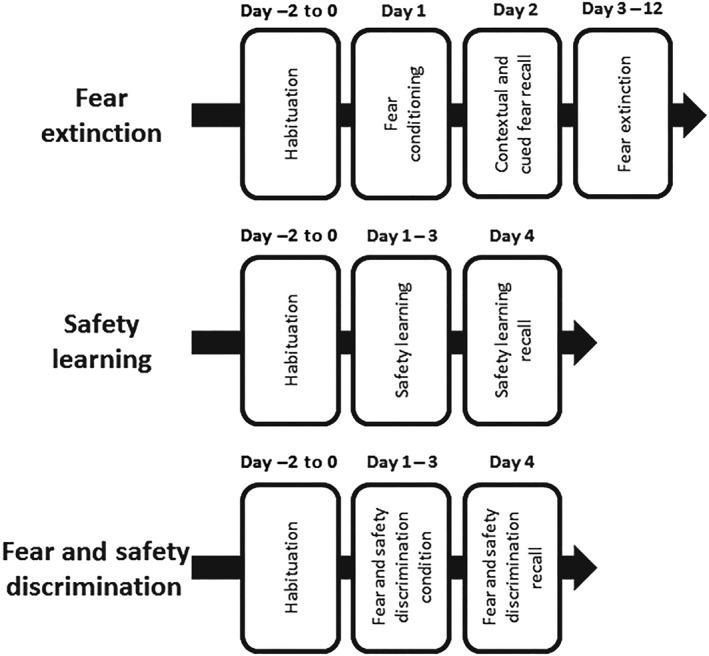

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of the fear inhibition paradigms used in the current study

2.2.1. Experiment 1: Fear extinction

Two paradigms of fear conditioning were employed with differing levels of footshock intensity (n = 10 male and n = 10 female mice per paradigm; Jacobson et al., 2011). On Day 1, mice were habituated to Experimental Context A for 2 min before presentation of five tone stimuli (CS+; 5 kHz, 80 dB, 10 s; inter‐trial interval [ITI] = 60 s) which co‐terminated with a footshock (moderate paradigm: 0.6 mA, 1 s; intense paradigm: 0.8 mA, 2 s). On Day 2, mice were placed in Experimental Context A for the assessment of contextual fear recall for 3 min before being returned to their home cage. Two hours later, mice were placed in Experimental Context B for the assessment of contextual fear generalisation and cued fear recall. Following a 30‐s habituation period, mice were presented with the same tone stimuli utilised during conditioning, however, without co‐terminating footshocks. An identical session was repeated every 24 hr thereafter for the assessment of fear extinction. A total of 10 fear extinction sessions were performed.

2.2.2. Experiment 2: Safety learning

Mice (n = 14 males; n = 14 females) were tested consecutively across 4 days during safety learning (Pollak et al., 2010). Only one experimental context was utilised during the experiment (square‐shaped chamber with a stainless steel floor underlying shock grid). On Day 1, mice were habituated to the experimental context for 2 min before presentation of five tone stimuli (CS−; 80 dB, 30 s), which were explicitly unpaired with a footshock (0.6 mA, 2 s). That is, the footshocks were administered at pseudorandom time points in between two tone stimuli (mean ITI: 120 s; range: 60–180 s) but not closer than 30 s to a tone. On Days 2 and 3, mice were returned to the experimental context and habituated for 30 s. The same stimuli (both auditory and footshocks) were presented. Timing of stimuli differed across each conditioning session; however, the ITI mean and range remained the same. Safety learning recall was assessed on Day 4. Mice were placed in the experimental context and 30 s later exposed to the same auditory tones presented during safety learning conditioning (ITI = 30 s) but without interleaving footshocks.

2.2.3. Experiment 3: Fear–safety discrimination

Mice (n = 10 males; n = 10 females) were tested consecutively across 4 days during fear–safety discrimination testing. On Day 1, mice were habituated to Experimental Context A for 2 min before presentation of five tone stimuli (5 kHz, 80 dB, 30 s) and five white‐noise stimuli (80 dB, 30 s). One stimulus (fear stimulus, CS+) co‐terminated with a footshock (0.6 mA, 2 s), whereas the other was never paired with a footshock (safety stimulus, CS−). Stimulus allocation to the CS+ or CS− was counterbalanced across the study. Intervals separating stimuli varied in duration (mean ITI: 120 s; range: 60–180 s). On Days 2 and 3, mice were returned to Experimental Context A and habituated for 30 s. The same stimuli (both auditory and footshocks) were presented. The timing of stimuli differed across each conditioning session; however, the ITI mean and range remained the same. Fear–safety discrimination was assessed on Day 4. Mice were placed in context B and after 30 s exposed to five CS+ stimuli, which were interleaved by five CS− stimuli (ITI = 30 s). No footshocks were administered in this session.

2.3. Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis in this study comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data consisted of two dependent variables: (a) percent time freezing (freezing %) or (b) number of jumps counted. Baseline freezing data were analysed using a series of independent measures t tests. All other data were analysed using a series of one‐way repeated measures ANOVA. Holm–Sidak post hoc analyses were conducted when the F statistic was significant for ANOVA factors, and the homogeneity of variance parametric assumption was not violated (Wei, Carroll, Harden, & Wu, 2012). Additionally, non‐linear regression was employed for the analysis of rates of fear extinction over time. The data were analysed via Graphpad Prism version 7 (RRID:SCR_002798; California, USA) or Sigmastat version 4 (California, USA). Statistical significance was accepted with P ≤ 0.05.

For each experiment, between‐group differences in baseline data were assessed during the 2‐min habituation period of the initial conditioning session. In Experiment 1, data during the CS+ were analysed for (a) fear conditioning, (b) cued fear recall, and (c) initial fear extinction (i.e., the session following cued fear recall). For these analyses, the between‐subject factor was defined as “sex,” and the within‐subject factor was defined as “trial.” For analysis of contextual fear recall, data in the first 90 s were binned into 30 s epochs (between‐subject factor = sex; within‐subject factor = epoch). Between‐group differences in baseline data during the 30 s baseline period of the cued fear recall session were assessed as a measure of contextual fear generalisation. For the analysis of fear extinction over time (i.e., across 10 fear extinction sessions following cued fear recall), data during trials of the CS+ were averaged within session (between‐subject factor = sex; within‐subject factor = fear extinction session). In Experiment 2, conditioned safety in the first session was assessed by comparing data in the final CS− with the 30 s period following the CS− (post CS−). For Conditioning Sessions 2 and 3, as well as safety learning recall, data expressed for each CS− and post CS− were averaged within each session and analysed (between‐group factor = sex; within‐subject factor = stimulus). In Experiment 3, data during the final presentation of the CS+ and CS− of the first conditioning session were analysed (between‐group factor = sex; within‐subject factor = stimulus). Conversely, for Conditioning Sessions 2 and 3, as well as discrimination recall, responses to the CS+ and CS− were averaged within each session and analysed (between‐group factor = sex; within‐subject factor = stimulus).

3. RESULTS

In the current study, freezing and jumping behaviours were assessed as indices of fear. However, jumping behaviour presented only infrequently during all experiments, except during acquisition of fear conditioning in the intense paradigm (Experiment 1). Therefore, other than for jumping data collected during fear conditioning in the intense paradigm, freezing data only are reported in the following results sections. Detailed results of statistical analyses for Experiments 1, 2, and 3 are presented in Supplementary tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

3.1. Experiment 1: Fear extinction

3.1.1. Acquisition of conditioned fear

During habituation, for both intensity paradigms, baseline freezing was minimal and not significantly different between groups (Supplementary Figure S1). During acquisition of fear conditioning, freezing increased significantly across CS+ trials for both the moderate and intense paradigms. However, the influence of ‘sex’ as well as the ‘sex’ x ‘trial’ interaction was not significant (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, jumping data reveal a different pattern across shock intensity levels, with significant increases in jumping illustrated across CS+ trials for the intense paradigm, relative to the moderate paradigm. However, jumping behaviour was not affected by ‘sex’ and nor was ‘sex’ x ‘trial’ interaction significant (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Sex differences in a fear extinction model (mean ± SEM per protocol, males, n = 10; females, n = 10): (a) Jumping behaviour during fear conditioning. Jumping increased significantly among male and female mice allocated to the intense protocol only. (b) Freezing across three epochs of contextual fear recall. For the intense protocol only, males, compared with females, presented with significantly greater freezing. (c) Freezing during the initial fear extinction session. For the intense protocol only, freezing was significantly different between males and females. (d) Freezing across fear extinction sessions tested over time (freezing to the CS+ averaged within session). For the intense protocol only, males, when compared with females, demonstrated a much steeper fear extinction curve. Freezing in the presence of the CS+ during the initial fear extinction session were averaged and included as Session 1 in fear extinction over time data. *P<0.05, significant main effects; # P<0.05, significant differences between sexes within session

3.1.2. Contextual fear recall and generalisation

In the moderate paradigm, freezing across epochs during contextual fear recall was not significantly different. Further, the effects of sex as well as the ‘sex’ x ‘epoch’ interaction were non‐significant. By contrast, for the intense paradigm, freezing increased significantly across epochs and was significantly greater among males, compared to females (Figure 2b). The ‘sex’ x ‘epoch’ interaction, though, was not significant. Regarding contextual fear generalisation to an alternative context, our data revealed non‐significant differences between males and females for both intensity paradigms (Supplementary Figure S3).

3.1.3. Recall and extinction of cued fear

Regarding cued fear recall, freezing during the CS+ significantly increased across trials for both shock intensity paradigms. Further, the influence of sex trended toward significance for the intense paradigm (males exhibited higher freezing) but not the moderate paradigm. On the other hand, the ‘sex’ x ‘trial’ interaction was non‐significant for both intensity paradigms (Supplementary Figure S4). In the subsequent test session (i.e., initial fear extinction), for the moderate intensity paradigm, freezing decreased significantly across CS+ trials. However, the effect of sex and the ‘sex’ x ‘trial’ interaction were non‐significant. By contrast, for the intense paradigm, freezing did not significantly differ across CS+ trials, although it was significantly greater for males, relative to females. Again, the ‘sex’ x ‘trial’ interaction was non‐significant (Figure 2c).

Regarding fear extinction over time, for the moderate paradigm, freezing in response to the CS+ decreased significantly across the ten sessions tested. However, the influence of sex and the ‘sex’ x ‘fear extinction session’ interaction were not significant. Moreover, non‐linear regression did not exhibit a significant difference in extinction rate for males versus females. Similarly, for the intense paradigm, freezing during the CS+ decreased significantly across fear extinction sessions and was non‐significantly different between males and females. However, the ‘sex’ x ‘fear extinction session’ interaction was significant, and post‐hoc analyses revealed between‐group differences in fear extinction sessions one and seven. Furthermore, non‐linear regression exhibited significant differences in the extinction rate between males and females, such that the curve was steeper for males (α = 67.5, β = ‐6.56; where y = α + βx) when compared to females (α = 54.42, β = ‐3.9; Figure 2d).

3.2. Experiment 2: Safety learning

3.2.1. Acquisition of safety learning

During habituation, baseline freezing was minimal and non‐significantly different between groups (Supplementary Figure S5). For the first safety conditioning session, analysis revealed significantly less freezing in the presence of the final CS‐, compared to the final post CS‐. However, sex differences and the ‘sex’ x ‘stimulus’ interaction were non‐significant. For conditioning sessions two and three, freezing during the CS‐ was significantly less than during the post CS‐ when averaged separately within each session. Again, however, data demonstrate a non‐significant effect of sex as well as ‘sex’ x ‘stimulus’ interaction (Supplementary Figure S6).

3.2.2. Recall of safety learning conditioning

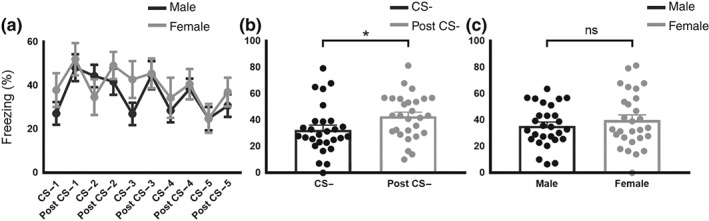

In safety learning recall, lower freezing was observed in response to the CS‐ when compared to the post CS‐ for males and females (Figure 3a). Accordingly, freezing during the CS‐ and post CS‐ period, when averaged within this session, were significantly different (Figure 3b). By contrast, the influence of sex (Figure 3c) and the ‘sex’ x ‘stimulus’ interaction were non‐significant.

Figure 3.

Sex differences in safety learning recall (mean ± SEM males, n = 14; females, n = 14): (a) pattern of discrimination between the CS− and post CS− illustrated in the safety recall session. Freezing response to stimuli are plotted in the order presented during testing. (b) Freezing response to the CS− and Post CS− period averaged within session. Mice (males and females) demonstrated significant differences in freezing response between stimuli. (c) Males and females did not differ in general levels of freezing %. *P<0.05, significant main effect. ns: non‐significant

3.3. Experiment 3: Fear–safety discrimination

3.3.1. Acquisition of fear–safety discrimination

During habituation, baseline freezing was minimal and non‐significantly different between groups (Supplementary Figure S7). For fear‐safety conditioning session one, freezing in response to the final CS+ and CS‐ were not significantly different. Sex differences and the ‘stimulus’ x ‘sex’ interaction were also not significant. Further, for conditioning sessions two and three, freezing during the CS+ and CS‐, when averaged separately within each session, were not significantly different. Again, the data demonstrate a non‐significant effect of sex and ‘sex’ x ‘stimulus’ interaction (Supplementary Figure S7).

3.3.2. Fear–safety discrimination recall

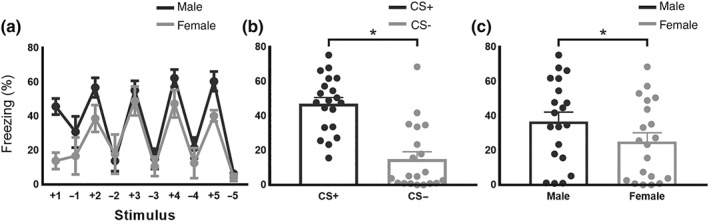

In fear‐safety discrimination recall, freezing during the CS+ was visibly higher than during the CS‐, indicating successful discrimination between fear and safety cues (Figure 4a). When averaged separately, freezing during the CS+ was significantly greater than the CS‐ (Figure 4b). Further, freezing during CS+ was significantly higher for males compared to females (Figure 4c). Conversely, the ‘sex’ x ‘stimulus’ interaction was not significant.

Figure 4.

Sex differences in fear–safety discrimination (mean ± SEM males, n = 10; females, n = 10): (a) the pattern of discrimination between the CS+ and CS− demonstrated in the fear and safety recall session. Freezing responses to stimuli are plotted in the order they were presented during testing. (b) Freezing, averaged within session, was greater for the CS+ than the CS− and were higher in (c) males than in females. *P<0.05, significant main effects

4. DISCUSSION

The current study investigated whether sex differences affect performance in specific mouse models of fear inhibition. In the fear extinction model, our data show that sex differences exist during contextual, but not cued, recall of fear. Further, the initial session of fear extinction, as well as fear extinction over time, was also influenced by sex. Our model of safety learning, conversely, did not exhibit differences between male and female mice. By contrast, the fear–safety discrimination model demonstrated freezing responses during recall were influenced by sex. Thus, the current study indicates that sex is a factor that influences specific components of fear inhibition processes in C57Bl/6J mice. Specifically, we provide important evidence to suggest that response to cues representing danger, but not safety, are influenced by sex. Therefore, preclinical neuro‐pharmacological studies in rodents (more specifically in C57Bl/6J mice), and particularly those investigating fear‐based processes, should be carried out in both sexes.

As indices of natural defensive behaviour, freezing as well as jumping were assessed in the current study. These behaviours represent differing responses to immediate threat stimuli (Blanchard, Griebel, & Blanchard, 2001). Specifically, whereas freezing is considered a reliable index of fear, jumping is thought to reflect a more intense, escape‐based behaviour (Blanchard et al., 2001; Lang, Davis, & Ohman, 2000). While footshock pain thresholds are not influenced by sex in C57Bl/6 mice (Podhorna, McCabe, & Brown, 2002), female rodents, compared to males, are considered more vulnerable to acute stressors (Kokras & Dalla, 2014). Thus, studies have revealed that the prevalence of jumping is highest among female rodents (Day et al., 2016; Pereira‐Figueiredo et al., 2017). In the current study, jumping was exhibited infrequently by males and females across all fear inhibition models tested. A critical exception, however, was during the fear extinction model, where jumping presented more frequently in the intense paradigm of fear conditioning, compared to the moderate paradigm. This finding supports the definition of these paradigms being moderate versus intense. In contrast, freezing presented consistently across all experiments of the current study, and therefore, the models of behaviour employed are considered predominantly reliable in inducing fear, though not escape‐based behaviour.

Our fear extinction model shows sex differences which were dependent on the intensity of footshock administered. Indeed, sex differences were not found to influence any outcome of interest assessed following the moderate paradigm of fear conditioning. Regarding the intense paradigm, however, male mice exhibited greater retention of fear in sessions most proximal to fear conditioning. These findings align with studies revealing a greater immediate conditioned fear response among males, compared with females (Kokras & Dalla, 2014; Villasana, Rosenberg, & Raber, 2010). In contrast, we did not observe sex differences in contextual fear generalisation or the recall of cued fear, which is at odds with previous reports (Villasana et al., 2010). We also demonstrated that males show an initial failure in the acquisition of fear extinction but exhibit more rapid fear extinction when tested over 10 sessions. These findings align with studies illustrating that male mice extinguish fear sooner than females (Graham & Milad, 2013; Matsuda et al., 2015). Taken together, the current study illustrates sex differences are more prominent following intense fear conditioning paradigms. Moreover, while male mice respond initially with greater fear, female mice exhibit slower fear extinction over time.

Safety learning in the current study revealed males and females exhibit an equal ability to establish learned safety. Mouse models which examine safety learning are relatively novel and, consequently, studies utilising these models, particularly to investigate sex differences, are scarce (Pollak et al., 2010). To date, only one study has examined safety learning processes in orexin‐deficient male and female mice (Khalil & Fendt, 2017). This study similarly revealed that safety learning was not influenced by sex. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to investigate safety learning in both male and female C57Bl/6J mice, arguably one of the most commonly used strains in preclinical pharmaco‐behavioural investigations. Sex differences in behavioural processes are thought to reflect fundamental differences in underlying structure, biology, and chemistry of the brain (Cahill, 2006). Thus, findings of the current study suggest that the neurophysiology of safety learning may not differ substantially between males and females. Therefore, findings of safety learning studies employing male subjects may be generalisable to females, at least with regard to mice.

Finally, the fear–safety discrimination model examined whether sex differences exist in discrimination between “threat” and “safe” conditioned stimuli. Importantly, this model tested fear and safety processing simultaneously, rather than independently, which was the case in Experiments 1 and 2. For both males and females, freezing data suggest initial impairment in discrimination between fear and safety stimuli during conditioning, which aligns with extant studies with rats (Day et al., 2016). Our data, however, demonstrate robust fear–safety discrimination during recall. This may potentially be due to the addition of an alternative context, which controlled for the contextual fear driving high freezing in response to safety stimuli during conditioning. Moreover, during recall, our data reveal greater general levels of freezing among males, compared to females. This is consistent with previous studies with rats, which also illustrated that males exhibit greater freezing during discrimination recall (Day et al., 2016; Foilb, Bals, Sarlitto, & Christianson, 2018). These findings are similar to those observed in contextual fear recall as well as the initial fear extinction session of Experiment 1, which suggests that the conditioning protocol employed in the fear–safety discrimination paradigm was intense. Moreover, our data demonstrate initial cued fear generalisation in male mice, which was not apparent in females and which may have masked initial safety learning effects. By the second trial of the CS−, however, sex differences in freezing response to the safety cue were no longer exhibited.

Together, our findings demonstrate that fear processes, but not safety processes per se, are influenced by sex. Specifically, in C57Bl/6J mice, these differences were illustrated in the fear extinction and fear–safety discrimination model of fear inhibition. In contrast, the safety learning model, as well as the safety component of the fear–safety discrimination model, did not reveal major sex differences. This may reflect important sex differences in neurocircuitry involved in fear, but not safety‐related, processes. Specifically, neural structures that mediate response to threat, such as the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, demonstrate sex differences (Gruene, Roberts, Thomas, Ronzio, & Shansky, 2015; McClure et al., 2004). Furthermore, previous studies in rodents have shown that http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=1013 levels influence processing of fear memory (Milad et al., 2009). We did not assess oestrous cycle in the current study, although our data demonstrate that robust sex differences were present in specific fear inhibition processes, irrespective of oestrous phase.

Fear and safety‐based processes are preserved across species, and therefore, findings of studies examining these processes are often translatable (VanElzakker, Dahlgren, Davis, Dubois, & Shin, 2014). As in the present study, in a healthy human population, men showed heightened immediate fear response to conditioned stimuli compared to women (Milad et al., 2006) but extinguished fear more rapidly (Milad et al., 2010). Further, sex differences between men and naturally cycling women were not demonstrated in objective fear responses to stimuli reflecting safety (Lonsdorf et al., 2015). Mouse paradigms of fear inhibition, thus, may be particularly useful for the development of understanding of mechanisms that underlie differential responses to fear versus safety learning between sexes. For example, studies with rats have identified neurocircuitry underlying fear extinction processes and examined ways of manipulating this circuitry (Milad & Quirk, 2012; Ter Horst, Carobrez, van der Mark, de Kloet, & Oitzl, 2012). However, the majority of these studies have used males (Beery & Zucker, 2011; Wald & Wu, 2010). Results of the present study suggest that it is inappropriate to generalise findings across sexes in studies investigating fear‐related processes and particularly with regard to cued fear conditioning using intense conditioning protocols. Future preclinical pharmaco‐behavioural studies should therefore use both males and females when examining such processes.

In conclusion, here we have presented three models of fear inhibition in C57Bl6/J mice that may be engaged for testing pharmacological agents targeting fear inhibition processes. Males displayed greater immediate fear response to fear‐conditioned stimuli but faster fear extinction when assessed over time. Conversely, contextual safety learning was not influenced by sex. Thus, cued fear inhibition processes in males should not be generalised to females, or vice versa, and inclusion of both males and females in related studies is therefore important. Stress‐related psychiatric disorders, especially PTSD, are prevalent in women (Kilpatrick et al., 2013; McLean et al., 2011) and associated with fear inhibition impairment (Jovanovic et al., 2012). The current study suggests that extinction of cued fear, but not safety learning, may be a dominant contributor to this sex difference.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.H.J., S.P.A.D., D.H. and J.W.C. conceived the research project. J.W.C. performed experiments. J.W.C. and L.H.J. wrote the manuscript with critical input from S.P.A.D. and D.H. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bph.14207, and https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bph.14206, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1.

Experiment One (fear extinction model); baseline freezing % for both moderate and intense paradigms during a two‐minute habituation period were minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S2.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model); freezing % for both the moderate and intense paradigm during fear conditioning. For both intensity paradigms, freezing % increased across CS+ trials, though was not influenced by sex.

Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model); freezing % for both the moderate and intense paradigm during fear conditioning. For both intensity paradigms, freezing % increased across CS+ trials, though was not influenced by sex.

Figure S3. Experiment One (fear extinction model); baseline freezing % for both moderate and intense paradigms during a 30‐s baseline period during the cued fear recall session were not significantly different between groups.

Figure S4.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model), recall of conditioned fear; Freezing % for moderate and intense paradigms during the recall of cued fear. For both paradigms, freezing % increased across trials of the CS+, though was not influenced by sex.

Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model), recall of conditioned fear; Freezing % for moderate and intense paradigms during the recall of cued fear. For both paradigms, freezing % increased across trials of the CS+, though was not influenced by sex.

Figure S5. Experiment Two (safety learning model); baseline freezing % during a two‐minute habituation period was minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S6.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment Two (safety learning model); Freezing % in the CS‐ and Post CS‐ across three safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in response to the final CS‐ and post CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For conditioning sessions two and three, freezing % in the presence of the CS‐ and post CS‐ were averaged separately within‐session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Female; Experiment Two (safety learning model); Freezing % in the CS‐ and Post CS‐ across three safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in response to the final CS‐ and post CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For conditioning sessions two and three, freezing % in the presence of the CS‐ and post CS‐ were averaged separately within‐session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Figure S7. Experiment Three (fear‐safety discrimination model); baseline freezing % during a two‐minute habituation period was minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S8.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment Three (Fear‐safety discrimination model); Freezing % in the CS+ and CS‐ across three fear and safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in the final CS+ and CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For sessions two and three, freezing % in response to the CS+ and CS‐ were averaged separately within each session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Female; Experiment Three (Fear‐safety discrimination model); Freezing % in the CS+ and CS‐ across three fear and safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in the final CS+ and CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For sessions two and three, freezing % in response to the CS+ and CS‐ were averaged separately within each session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Supplementary Table 1. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment One.

Supplementary Table 2. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment Two

Supplementary Table 3. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment Three

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the expert technical assistance of Brett Purcell (Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, Behaviour Facility) and Simon Miller (Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, Information Technology). L.H.J. and D.H. are supported by the NHMRC Project Grant 1105284 and the Alzheimer's Association NIRG‐396905. The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health acknowledge the support of the Victorian Government and in particular the funding from the Operational Infrastructure Support Grant.

Clark JW, Drummond SPA, Hoyer D, Jacobson LH. Sex differences in mouse models of fear inhibition: Fear extinction, safety learning, and fear–safety discrimination. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:4149–4158. 10.1111/bph.14600

REFERENCES

- Beery, A. K. , & Zucker, I. (2011). Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 565–572. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, D. C. , Griebel, G. , & Blanchard, R. J. (2001). Mouse defensive behaviors: Pharmacological and behavioral assays for anxiety and panic. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 25(3), 205–218. 10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, M. E. , & Ressler, K. J. (2015). An overview of translationally informed treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: Animal models of Pavlovian fear conditioning to human clinical trials. Biological Psychiatry, 78(5), E15–E27. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudey, C. , Park, J. , Wiaderkiewicz, J. , Kobayashi, I. , Mellman, T. A. , & Marvar, P. J. (2015). Autonomic and inflammatory consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and the link to cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 309(4), R315–R321. 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, L. (2006). Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 7(6), 477–484. 10.1038/nrn1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Alexander, S. , Cirino, G. , Docherty, J. R. , George, C. H. , Giembycz, M. A. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: Updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175(7), 987–993. 10.1111/bph.14153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, H. L. L. , Reed, M. M. , & Stevenson, C. W. (2016). Sex differences in discriminating between cues predicting threat and safety. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 133, 196–203. 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foilb, A. R. , Bals, J. , Sarlitto, M. C. , & Christianson, J. P. (2018). Sex differences in fear discrimination do not manifest as differences in conditioned inhibition. Learning & Memory, 25(1), 49–53. 10.1101/lm.045500.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B. M. , & Milad, M. R. (2013). Blockade of estrogen by hormonal contraceptives impairs fear extinction in female rats and women. Biological Psychiatry, 73(4), 371–378. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruene, T. M. , Roberts, E. , Thomas, V. , Ronzio, A. , & Shansky, R. M. (2015). Sex‐specific neuroanatomical correlates of fear expression in prefrontal‐amygdala circuits. Biological Psychiatry, 78(3), 186–193. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, L. H. , Commerford, S. R. , Gerber, S. P. , Chen, Y. A. , Dardik, B. , Chaperon, F. , … Teixeira, S. (2011). Characterization of a novel, brain‐penetrating CB1 receptor inverse agonist: Metabolic profile in diet‐induced obese models and aspects of central activity. Naunyn‐Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology, 384(6), 565–581. 10.1007/s00210-011-0686-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, T. , Kazama, A. , Bachevalier, J. , & Davis, M. (2012). Impaired safety signal learning may be a biomarker of PTSD. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 695–704. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, T. , & Norrholm, S. D. (2011). Neural mechanisms of impaired fear inhibition in posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 5, 44 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 5), 4–12. discussion 13‐14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Chiu, W. T. , Demler, O. , Merikangas, K. R. , & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12‐month DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, R. , & Fendt, M. (2017). Increased anxiety but normal fear and safety learning in orexin‐deficient mice. Behavioural Brain Research, 320, 210–218. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny, C. , Browne, W. , Cuthill, I. C. , Emerson, M. , & Altman, D. G. (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: The ARRIVE guidelines. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160, 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, D. G. , Resnick, H. S. , Milanak, M. E. , Miller, M. W. , Keyes, K. M. , & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM‐IV and DSM‐5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. 10.1002/jts.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokras, N. , & Dalla, C. (2014). Sex differences in animal models of psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171(20), 4595–4619. 10.1111/bph.12710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, P. J. , Davis, M. , & Ohman, A. (2000). Fear and anxiety: Animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 137–159. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00343-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf, T. B. , Haaker, J. , Schumann, D. , Sommer, T. , Bayer, J. , Brassen, S. , … Kalisch, R. (2015). Sex differences in conditioned stimulus discrimination during context‐dependent fear learning and its retrieval in humans: The role of biological sex, contraceptives and menstrual cycle phases. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(6), 368–375. 10.1503/jpn.140336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. J. , Acheson, D. T. , Risbrough, V. B. , Straus, L. D. , & Drummond, S. P. (2014). Fear conditioning, safety learning, and sleep in humans. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(35), 11754–11760. 10.1523/jneurosci.0478-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, S. , Matsuzawa, D. , Ishii, D. , Tomizawa, H. , Sutoh, C. , & Shimizu, E. (2015). Sex differences in fear extinction and involvements of extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK). Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 123, 117–124. 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure, E. B. , Monk, C. S. , Nelson, E. E. , Zarahn, E. , Leibenluft, E. , Bilder, R. M. , … Pine, D. S. (2004). A developmental examination of gender differences in brain engagement during evaluation of threat. Biological Psychiatry, 55(11), 1047–1055. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C. P. , & Anderson, E. R. (2009). Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 496–505. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C. P. , Asnaani, A. , Litz, B. T. , & Hofmann, S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(8), 1027–1035. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad, M. R. , Goldstein, J. M. , Orr, S. P. , Wedig, M. M. , Klibanski, A. , Pitman, R. K. , & Rauch, S. L. (2006). Fear conditioning and extinction: Influence of sex and menstrual cycle in healthy humans. Behavioral Neuroscience, 120(6), 1196–1203. 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad, M. R. , Igoe, S. A. , Lebron‐Milad, K. , & Novales, J. E. (2009). Estrous cycle phase and gonadal hormones influence conditioned fear extinction. Neuroscience, 164(3), 887–895. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad, M. R. , & Quirk, G. J. (2012). Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: Ten years of progress. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 129–151. 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad, M. R. , Zeidan, M. A. , Contero, A. , Pitman, R. K. , Klibanski, A. , Rauch, S. L. , & Goldstein, J. M. (2010). The influence of gonadal hormones on conditioned fear extinction in healthy humans. Neuroscience, 168(3), 652–658. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanza, P. , & Parmigiani, S. (2017). How does sex matter? Behavior, stress and animal models of neurobehavioral disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 76(Pt A), 134–143. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira‐Figueiredo, I. , Castellano, O. , Riolobos, A. S. , Ferreira‐Dias, G. , Lopez, D. E. , & Sancho, C. (2017). Long‐term sertraline intake reverses the behavioral changes induced by prenatal stress in rats in a sex‐dependent way. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 11, 99 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podhorna, J. , McCabe, S. , & Brown, R. E. (2002). Male and female C57BL/6 mice respond differently to diazepam challenge in avoidance learning tasks. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 72(1–2), 13–21. 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00783-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, D. D. , Monje, F. J. , & Lubec, G. (2010). The learned safety paradigm as a mouse model for neuropsychiatric research. Nature Protocols, 5(5), 954–962. 10.1038/nprot.2010.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsawh, H. J. , Fullerton, C. S. , Mash, H. B. , Ng, T. H. , Kessler, R. C. , Stein, M. B. , & Ursano, R. J. (2014). Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the U.S. Army. Journal of Affective Disorders, 161, 116–122. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Horst, J. P. , Carobrez, A. P. , van der Mark, M. H. , de Kloet, E. R. , & Oitzl, M. S. (2012). Sex differences in fear memory and extinction of mice with forebrain‐specific disruption of the mineralocorticoid receptor. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 36(8), 3096–3102. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanElzakker, M. B. , Dahlgren, M. K. , Davis, F. C. , Dubois, S. , & Shin, L. M. (2014). From Pavlov to PTSD: The extinction of conditioned fear in rodents, humans, and anxiety disorders. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 113, 3–18. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villasana, L. , Rosenberg, J. , & Raber, J. (2010). Sex‐dependent effects of 56Fe irradiation on contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6J mice. Hippocampus, 20(1), 19–23. 10.1002/hipo.20659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voulo, M. E. , & Parsons, R. G. (2017). Response‐specific sex difference in the retention of fear extinction. Learning & Memory, 24(6), 245–251. 10.1101/lm.045641.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald, C. , & Wu, C. (2010). Biomedical research. Of mice and women: The bias in animal models. Science, 327(5973), 1571–1572. 10.1126/science.327.5973.1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J. , Carroll, R. J. , Harden, K. K. , & Wu, G. (2012). Comparisons of treatment means when factors do not interact in two‐factorial studies. Amino Acids, 42(5), 2031–2035. 10.1007/s00726-011-0924-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan, M. A. , Igoe, S. A. , Linnman, C. , Vitalo, A. , Levine, J. B. , Klibanski, A. , … Milad, M. R. (2011). Estradiol modulates medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala activity during fear extinction in women and female rats. Biological Psychiatry, 70(10), 920–927. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.

Experiment One (fear extinction model); baseline freezing % for both moderate and intense paradigms during a two‐minute habituation period were minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S2.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model); freezing % for both the moderate and intense paradigm during fear conditioning. For both intensity paradigms, freezing % increased across CS+ trials, though was not influenced by sex.

Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model); freezing % for both the moderate and intense paradigm during fear conditioning. For both intensity paradigms, freezing % increased across CS+ trials, though was not influenced by sex.

Figure S3. Experiment One (fear extinction model); baseline freezing % for both moderate and intense paradigms during a 30‐s baseline period during the cued fear recall session were not significantly different between groups.

Figure S4.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model), recall of conditioned fear; Freezing % for moderate and intense paradigms during the recall of cued fear. For both paradigms, freezing % increased across trials of the CS+, though was not influenced by sex.

Female; Experiment One (fear extinction model), recall of conditioned fear; Freezing % for moderate and intense paradigms during the recall of cued fear. For both paradigms, freezing % increased across trials of the CS+, though was not influenced by sex.

Figure S5. Experiment Two (safety learning model); baseline freezing % during a two‐minute habituation period was minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S6.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment Two (safety learning model); Freezing % in the CS‐ and Post CS‐ across three safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in response to the final CS‐ and post CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For conditioning sessions two and three, freezing % in the presence of the CS‐ and post CS‐ were averaged separately within‐session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Female; Experiment Two (safety learning model); Freezing % in the CS‐ and Post CS‐ across three safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in response to the final CS‐ and post CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For conditioning sessions two and three, freezing % in the presence of the CS‐ and post CS‐ were averaged separately within‐session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Figure S7. Experiment Three (fear‐safety discrimination model); baseline freezing % during a two‐minute habituation period was minimal and not significantly different between groups.

Figure S8.

Male;

Male; Female; Experiment Three (Fear‐safety discrimination model); Freezing % in the CS+ and CS‐ across three fear and safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in the final CS+ and CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For sessions two and three, freezing % in response to the CS+ and CS‐ were averaged separately within each session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Female; Experiment Three (Fear‐safety discrimination model); Freezing % in the CS+ and CS‐ across three fear and safety conditioning sessions. For conditioning session one, freezing % in the final CS+ and CS‐ were compared. Freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex. For sessions two and three, freezing % in response to the CS+ and CS‐ were averaged separately within each session. Again, freezing % did not differ between stimulus type or sex.

Supplementary Table 1. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment One.

Supplementary Table 2. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment Two

Supplementary Table 3. Statistical results of analyses performed for assessment of outcomes in Experiment Three