The plant metabolic enzyme aldo-keto reductase has evolved to metabolize glyphosate in a glyphosate-resistant weed species

Abstract

Glyphosate, the most commonly used herbicide in the world, controls a wide range of plant species, mainly because plants have little capacity to metabolize (detoxify) glyphosate. Massive glyphosate use has led to world-wide evolution of glyphosate-resistant (GR) weed species, including the economically damaging grass weed Echinochloa colona. An Australian population of E. colona has evolved resistance to glyphosate with unknown mechanisms that do not involve the glyphosate target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-P synthase. GR and glyphosate-susceptible (S) lines were isolated from this population and used for resistance gene discovery. RNA sequencing analysis and phenotype/genotype validation experiments revealed that one aldo-keto reductase (AKR) contig had higher expression and higher resultant AKR activity in GR than S plants. Two full-length AKR (EcAKR4-1 and EcAKR4-2) complementary DNA transcripts were cloned with identical sequences between the GR and S plants but were upregulated in the GR plants. Rice (Oryza sativa) calli and seedlings overexpressing EcAKR4-1 and displaying increased AKR activity were resistant to glyphosate. EcAKR4-1 expressed in Escherichia coli can metabolize glyphosate to produce aminomethylphosphonic acid and glyoxylate. Consistent with these results, GR E. colona plants exhibited enhanced capacity for detoxifying glyphosate into aminomethylphosphonic acid and glyoxylate. Structural modeling predicted that glyphosate binds to EcAKR4-1 for oxidation, and metabolomics analysis of EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice seedlings revealed possible redox pathways involved in glyphosate metabolism. Our study provides direct experimental evidence of the evolution of a plant AKR that metabolizes glyphosate and thereby confers glyphosate resistance.

Glyphosate is the world’s most commonly used herbicide, with estimated annual use of 300 million pounds in the United States in recent years, owing to its high efficacy, broad spectrum, and systemic mode of action (Duke et al., 2018). Despite minimal resistance evolution in weeds during the first two decades of glyphosate use, the high adoption of glyphosate-tolerant transgenic crops from 1996 onwards imposed very high glyphosate selection pressure, resulting in widespread evolution of glyphosate resistance in the Americas. Since first reported (Powles et al., 1998; Pratley et al., 1999), evolution of glyphosate-resistant (GR) weeds has dramatically increased, mainly in the Americas and to a lesser extent in many other parts of the world (Duke and Powles, 2008; Duke et al., 2018). Currently, 304 populations of 42 weedy species have evolved resistance to glyphosate across six continents (Heap, 2019).

Given the widespread occurrence and importance of GR weed evolution, the biochemical and molecular basis of mechanisms endowing glyphosate resistance is under intensive study. Both target-site and non-target–site glyphosate resistance mechanisms exist (Sammons and Gaines, 2014). Specific mutations in the target enzyme of glyphosate, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-P synthase (EPSPS), can endow glyphosate resistance (Baerson et al., 2002; Sammons and Gaines, 2014; Yu et al., 2015; Gaines et al., 2019). Mutations in EPSPS have been documented at amino acid position Pro-106 (Sammons and Gaines, 2014), Thr-102 (Li et al., 2018), Thr-102+Pro-106 (the “TIPS” double mutation; Yu et al., 2015), and Thr-102+Ala-103+Pro-106 (the “TAP-IVS” triple mutation; Perotti et al., 2019). Additionally, many-fold increases in EPSPS gene amplification endows resistance by EPSPS overproduction (Gaines et al., 2010), and this mechanism has been reported in eight weedy species (Patterson et al., 2018). Non-target–site glyphosate resistance due to restricted glyphosate translocation (Lorraine-Colwill et al., 2002) occurs in many GR weed species, and likely involves increased glyphosate sequestration to vacuoles (Ge et al., 2010). However, non-target–site glyphosate resistance mechanisms have been only elucidated at the biochemical level, and the molecular basis remains unknown.

Most plant species cannot significantly metabolize glyphosate, which is a major factor contributing to its lethality in plants. However, glyphosate is readily metabolized by a variety of soil microbes via a glyphosate oxidoreductase (GOX), which cleaves the glyphosate C–N bond forming amino methyl phosphonic acid (AMPA) and glyoxylate, and, to a lesser extent, via a C-P lyase, forming sarcosine and inorganic P (Barrett and McBride, 2005; Pizzul et al., 2009). Some plant species, notably legumes, can metabolize glyphosate, especially to AMPA, but without correlation to the level of tolerance to glyphosate (Reddy et al., 2008; Duke, 2011; Nandula et al., 2019). Studies on a wide range of GR weed species report no glyphosate metabolism (Sammons and Gaines, 2014). Only two reports show evidence of glyphosate metabolites (e.g. AMPA, sarcosine) in GR weeds, without further elaboration (de Carvalho et al., 2012; González-Torralva et al., 2012). Glyphosate metabolism to AMPA and glyoxylate in plants is likely due to plant GOX-like activities or horizontal gene transfer from microbes (Duke, 2011). However, neither GOX-like glyphosate-metabolizing enzymes nor their encoding genes have been identified in plant species, making their discovery a research priority (Duke, 2011).

Aldo-keto reductase (AKR) superfamilies are widely distributed in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Barski et al., 2008; Simpson et al., 2009), and typically catalyze NAD(P)(H)-dependent reduction of aldehydes and ketones under normal or stress conditions. Due to their broad substrate specificity, AKRs can also metabolize a large number of xenobiotics (Barski et al., 2008; Simpson et al., 2009; Penning, 2015). However, plant AKRs have not been well studied, with the most characterized being the AKR4C family involved in aldehyde detoxification and stress defense, osmolyte production, secondary metabolism, and membrane transport (Simpson et al., 2009; Penning, 2015). For example, AKR4C8 and AKR4C9 from Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) can reduce a range of toxic compounds containing reactive aldehyde groups (Simpson et al., 2009). In contrast, AKR4C7 from maize (Zea mays) catalyzes the oxidation of sorbitol to Glc (de Sousa et al., 2009). In addition, AKR17A1 from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp PCC7120 catalyzes the metabolism of the herbicide butachlor into dicarboxylic acid and phenol (Agrawal et al., 2015). Importantly, it has been recently reported that AKR genes from Pseudomonas AKR1 and rice (Oryza sativa; OsAKR1), when overexpressed in bacteria and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), showed improved glyphosate tolerance (Vemanna et al., 2017). However, these genes were experimentally derived, and how these AKRs detoxify glyphosate remains elusive.

Here, we used a GR Echinochloa colona (awnless barnyard grass) population (Gaines et al., 2012) in which the unknown glyphosate resistance mechanism is not based on the target site EPSPS and not due to reduced glyphosate uptake or translocation at the tissue level (Goh et al., 2018). Our preliminary work did not reveal glyphosate metabolism (Goh et al., 2018), but we observed that glyphosate resistance was influenced by temperature, indicating the involvement of metabolic and/or transporter proteins. In light of the work by Vemanna et al. (2017), we hypothesized that glyphosate metabolism mediated by a plant AKR may be involved in glyphosate resistance in this E. colona population. Using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we identified a novel AKR gene (designated as EcAKR4-1) in our GR E. colona population. Overexpression of EcAKR4-1 in transgenic rice endows glyphosate resistance, and Escherichia coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 converts glyphosate to AMPA and glyoxylate. Glyphosate metabolism in GR versus susceptible (S) E. colona plants was then re-examined using ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), which confirmed an enhanced capacity of the GR plants to detoxify glyphosate to AMPA and glyoxylate. We explored the structural interactions of EcAKR4-1 and glyphosate, and, based on these results together with a metabolomic analysis of EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice seedlings, we propose a possible EcAKR4-1-mediated redox pathway involved in glyphosate metabolism.

RESULTS

Consistent Upregulation of an AKR Contig in GR E. colona Plants

The GR and S individuals of a single GR (Rsingle) and a single S (Ssingle) line from within the GR E. colona population were selected for RNA-seq (Fig. 1). Consistent with our previous study (Goh et al., 2018), EPSPS expression was not significantly different between GR and S samples (Supplemental Table S1), excluding target-site based resistance in this population. Twelve AKR contigs were identified in RNA-seq analysis (Supplemental Table S1), and expression of one AKR contig (EC_v4.g051927) was significantly higher in GR versus S samples and hence selected for quantitative PCR (qPCR) validation. This AKR contig showed consistently higher expression (up to 5-fold; Table 1) in multiple GR compared to S E. colona lines and populations, including (1) three GR versus three S samples used for RNA-seq, (2) an additional six GR versus six S spare samples for RNA-seq, (3) 10 GR versus 10 S samples each from bulked GR (Rbulk) and S (Sbulk) populations, (4) 10 GR versus 10 S samples each from the Rsingle and Ssingle lines, and (5) 10 GR versus 10 S samples that were isolated from within each of the Rbulk and Rsingle lines (Table 1). Ten samples each from the two additional S populations (QBG1 and Crossy) were also analyzed against the 10 samples from the Ssingle line, and no increased expression of the AKR contig (EC_v4.g051927) was detected (Table 1) in the supplementary S lines. These results establish that higher expression of the AKR contig (EC_v4.g051927) correlates with glyphosate resistance in E. colona.

Figure 1.

Population resources used for RNA-seq and validation in this study.

Table 1. Validation of the E. colona candidate AKR contig (EC_v4.g051927) using a series of pre-phenotyped samples.

Significance of student t tests are indicated by *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. R, glyphosate-resistant; S, glyphosate-susceptible.

| Sample Sources | Relative Expression Ratio (R/S)a | P Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq results | 2.2 | 0.0001 | ** |

| Validation using RNA-seq samples | 4.9 | 0.006 | ** |

| Validation using spare RNA-seq samples | 4.8 | 0.0043 | ** |

| Validation using population/line samples | |||

| Rbulk/Sbulk | 4.6 | 0.0069 | ** |

| Rsingle/Ssingle | 4.8 | 0.0365 | * |

| Rbulk-R/Rbulk-S | 2.0 | 0.0277 | * |

| Rsingle-R/Rsingle-S | 2.5 | 0.0265 | * |

| QBG1 (S)/Ssingle | 0.9 | 0.2076 | — |

| Crossy (S)/Ssingle | 1.0 | 0.8469 | — |

| Rsingle (35°C/30°C)/Rsingle (25°C/20°C) | 2.9 | 0.0004 | ** |

Raw fragments per thousand bases per million reads for the RNA-seq results, and RT-qPCR validation for all others.

Importantly, the level of glyphosate resistance in the Rsingle line was influenced by temperature. When GR E. colona was grown at 35°C/30°C, all Rsingle plants survived 540 g of glyphosate ha−1, but when grown at 25°C/20°C, only 70% survived this glyphosate rate. Similarly, temperature had an impact on plant biomass. When treated with 540 g of glyphosate ha−1 at 35°C/30°C, Rsingle plants produced 95% of the biomass of untreated controls. However, at 25°C/20°C, Rsingle plants produced only 30% of the biomass of untreated controls. Therefore, expression of the AKR contig (EC_v4.g051927) was further tested for its response to temperature, and significantly higher expression (2.9-fold) was recorded under 35°C/30°C than 25°C/20°C growth temperatures (Table 1).

Full Sequence Cloning and Analysis of the AKR Genes

Full coding sequences of two AKR genes (AKR1 and AKR2, respectively) were cloned from GR and S E. colona. The two transcripts had the same complementary DNA (cDNA) length (933 bp) and showed 95% identity. Due to E. colona being a polyploid (Supplemental Fig. S1), these may be two homeologous AKR gene alleles or copies. Therefore, two specific primers, AKR1F/AKR1R and AKR2F/AKR2R (Supplemental Table S2) for AKR1 and AKR2, respectively, were designed to quantify the expression of these two transcripts in E. colona. As expected, a higher level of expression of both transcripts (5.1-fold for AKR1 and 4.8-fold for AKR2) was detected in the GR versus S samples used for RNA-seq.

Sequence alignment of the AKR1 and AKR2 genes between GR and S E. colona plants showed no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). In addition, AKR1 and AKR2 sequences from the two supplementary glyphosate-susceptible E. colona populations (QBG1 and Crossy) were also compared with the S line. No SNPs in AKR1 were found, but three SNPs in AKR2 were; however, these SNPs caused no amino acid changes.

Analysis using the National Center for Biotechnology Information conserved domain tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) identified AKR domains, confirming AKR1 and AKR2 belong to the AKR family. The E. colona AKR1 and AKR2 amino acid sequences were 93% similar to rice OsAKR4C10 (XP_015630643.1) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) AKR4C10 (XP_002456633.1), 85% similar to maize AKR4C7 (5JH2_A) and OsAKR1 (ABF97586.1), and only 25% similar to Pseudomonas AKR1 (PsAKR1, igrA; Acc. No. M37389). The nearest-neighbor analysis of characterized AKR protein sequences indicates that E. colona AKR1 and AKR2 have close evolutionary relationships with foxtail millet (Setaria italica) AKR4C10, assembled by forming a sister clade with Oryza brachyantha AKR4C9, and rice AKR1 and AKR2 (Supplemental Fig. S2). Based on the phylogenetic analysis, the E. colona AKR1 and AKR2 genes cloned in this study were designated as EcAKR4-1 and EcAKR4-2 (accession nos: MK592097 and MK592098), respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Untranslated Region Variations of the EcAKR4 gene

To assess possible underlying mechanisms for elevated AKR expression in GR E. colona plants, a 264-bp 5ʹ-untranslated region (UTR) located between the transcription start site and translation initiation site, and a 3ʹ-UTR region of 216 bp from the translation stop site, were obtained from five plants each of GR, S, and two supplementary S populations (QBG1 and Crossy). Sequence alignment showed only two SNPs in the 3ʹ-UTR, and 10 in the 5ʹ-UTR region between the GR and three S populations (Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that the 5ʹ-UTR may be involved in the regulation of expression and translation of EcAKR4-1.

Determination of AKR Activity in E. colona

To determine if higher EcAKR4 expression results in higher AKR activities, typical AKR activities (i.e. as reductases) were measured in GR versus S plants (Table 2) against a commonly used substrate, methylglyoxal. Higher (up to 3.2-fold) AKR activities were recorded in the GR than in the S plants, consistent with the higher EcAKR4 gene expression (up to 4.9-fold) in GR plants.

Table 2. AKR activities measured using methylglyoxal as a substrate in GR versus S lines/populations of E. colona, and T0 transgenic rice seedlings.

Data are means ± se (n = 3).

| Material | EcAKR Activity (µmol mg−1 min−1) |

|---|---|

| R plants from Rsingle | 5.8 (0.18) |

| R plants from Rbulked | 5.5 (0.23) |

| S plants from Ssingle | 2.2 (0.11) |

| S plants from Sbulked | 2.3 (0.17) |

| S plants-QBG1 population | 1.8 (0.14) |

| S plants-Crossy population | 2.5 (0.09) |

| EcAKR4-1-overexpressing T0 rice seedlings | 7.8 (0.22) |

| GFP-overexpressing T0 rice seedlings | 1.4 (0.17) |

Rice Calli Overexpressing EcAKR4-1 Are Less Sensitive to Glyphosate

As EcAKR4-1 showed a slightly higher identity to OsAKR1 (85%; Vemanna et al., 2017), and had a higher expression relative to EcAKR4-2, EcAKR4-1 was prioritized for functional confirmation using rice genetic transformation. Growth of rice calli overexpressing the EcAKR4-1 and GFP genes (the latter used as a negative control) were compared on glyphosate-containing medium. Growth of GFP-overexpressing rice calli was visibly inhibited at 0.5 mm of glyphosate, and there was no growth at 1 mm of glyphosate or higher (Fig. 2A). However, EcAKR4-1-overexpressing rice calli were less sensitive to glyphosate, with growth occurring at up to 4 mm glyphosate (Fig. 2A). It is evident that rice calli with EcAKR4-1 overexpression exhibit resistance to glyphosate, in comparison to the rice calli overexpressing the GFP control.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of EcAKR4-1 confers glyphosate resistance in rice. Growth response to glyphosate of rice calli (A), T0 (B), and T1 (C) seedlings transformed with the GFP (control) or EcAKR4-1 gene, three weeks after glyphosate treatment. Note only glyphosate surviving T1 seedlings from EcAKR4-1 overexpressing lines are shown in (C).

In contrast, rice calli overexpressing EcAKR4-1 and GFP were equally susceptible to the nonselective herbicide glufosinate (Supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting that EcAKR4-1 overproduction is not a general defense mechanism but a specific resistance mechanism to glyphosate selection.

Rice Seedlings Overexpressing EcAKR4-1 Are GR

Twelve regenerated T0 rice seedlings/transformants overexpressing the EcAKR4-1 or GFP gene were used for further testing. Reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR using primer pairs A1/A2 and B1/B2 and sequencing analysis confirmed transcription of the EcAKR4-1 or GFP gene in these 24 transgenic rice seedlings. Results showed that the EcAKR4-1 gene was expressed 8.5-fold higher in EcAKR4-1-overexpressing rice seedlings relative to the GFP-overexpressing rice seedling controls. Correspondingly, EcAKR4-1-overexpressing rice seedlings had a higher (5.6-fold) level of AKR activity (against methylglyoxal) than that of GFP-overexpressing rice seedlings (Table 2). As expected, the GFP-overexpressing rice plants were killed by foliar-applied glyphosate at rates of 540 g ha−1 or higher. However, the EcAKR4-1-overexpressing rice seedlings survived 540 and 1,080 glyphosate g ha−1 but died at 2,160 g glyphosate ha−1 (Fig. 2B). In addition, a total of 55 T1 seedlings from five EcAKR4-1 transgenic lines were screened at a glyphosate rate of 540 g ha−1 (Fig. 2C), and the resistance and susceptibility segregated at 42:13, fitting to a single gene control mode of 3:1 (X2 = 0.05, P = 0.82). These results clearly establish that overexpression of EcAKR4-1 in transgenic rice enhances AKR activity, conferring glyphosate resistance.

In Vitro Glyphosate Metabolism by E. coli-Expressed EcAKR4-1 Enzyme

The ability of EcAKR4-1 to degrade glyphosate was assessed using enzyme purified from transgenic E. coli. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the EcAKR4-1 enzyme was isolated as a single band around 35 kD, close to the deduced molecular weight of the EcAKR4-1 protein (Supplemental Fig. S5). The purified EcAKR4-1 enzyme, displaying the typical AKR ability to reduce the substrate methylglyoxal (88.5 ± 9.6 µmol mg−1 protein min−1), was incubated with glyphosate and the resulting products were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography combined with TOF mass spectrometry (HPLC-Q-TOF-MS). Standards of glyphosate and its possible metabolites (AMPA, glyoxylate, sarcosine, and formaldehyde) were resolved in the detection system (Fig. 3, sarcosine and formaldehyde not shown).

Figure 3.

HPLC-Q-TOF-MS analyses of glyphosate metabolism catalyzed by E. coli-expressed ECAKR4-1. A, One h after in vitro incubation. B, Five h after in vitro incubation. Standard: analytical grade glyphosate, AMPA, and glyoxylate. Control: mixture of glyphosate and plant tissue extract. Vector control: mixture of E. coli-expressed BSA protein, glyphosate, and plant tissue extract. EcAKR4-1: mixture of E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 enzyme, glyphosate, and plant tissue extract.

Analysis of the enzyme reaction mix showed that in addition to glyphosate, two peaks with retention times of 1.19 min and 1.38 min, corresponding to those of the AMPA and glyoxylate standards, respectively, were detected only in the presence of the EcAKR4-1 enzyme (Fig. 3). The mass spectra of the two metabolites were also the same as those of the AMPA (m/z = 112.0152) and glyoxylate (m/z = 133.0146) standards. In contrast, sarcosine and formaldehyde were not detected in the incubation mixture. Clearly, purified EcAKR4-1 could metabolize glyphosate in vitro. In seeking optimal conditions for in vitro glyphosate metabolism by purified EcAKR4-1, we found that AMPA production was low in the presence of NADPH, but 23-fold higher with NADP+ (Table 3). Addition of NADP+/NADPH only marginally increased AMPA production compared to NADPH. In contrast, replacement of NADP+/NADPH by boiled water extract of plant tissue dramatically enhanced AMPA production by 633-fold compared to NADP+ alone (Table 3), indicating the need for unknown plant tissue factors.

Table 3. In vitro production of the glyphosate metabolite AMPA by E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 enzyme in the reaction mixture (3 mL), as affected by respective addition of the following ingredients, 3 h after incubation with glyphosate at 25°C.

Data are means ± se (n = 3).

| Ingredient in the Reaction Mix | pH | AMPA (µg mL−1) |

|---|---|---|

| NADPH (0.1 mm) | 7.4 | 0.149 (0.006) |

| NADP+ (0.1 mm) | 5.8 | 3.436 (0.095) |

| NADP+/NADPH (0.1 mm) | 6.5 | 3.955 (0.058) |

| NADP+/NADPH (0.1 mm) | 7.5 | 4.219 (0.168) |

| Plant tissue (0.3-mL boiled water extract) | 6.8 | 94.33 (1.209) |

| Plant tissue (0.3 mL) + NADP+/NADPH (0.1 mm of each) | 6.7 | 95.09 (2.432) |

Therefore, plant tissue extract was used in the reaction mixture. Under these conditions, glyphosate conversion to AMPA and glyoxylate occurred such that by 5 h after treatment, glyphosate (1.48 mm) was completely converted to AMPA and glyoxylate (Figs. 3 and 4; Table 4). In contrast, no glyphosate metabolites were ever detected in controls at any time point (Fig. 3; Table 4). In addition, and in support of the plant growth and EcAKR4-1 expression results, glyphosate conversion to AMPA by E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 was enhanced at higher temperatures. For example, AMPA concentrations were 44%, 88%, 37%, and 34% higher at 35°C than at 25°C, at 1, 3, 5, and 7 h after treatment, respectively (Fig. 4; Table 4). Interestingly, changes in glyoxylate concentration did not follow the same trend (Fig. 4; Table 4), indicating the possibility of further degradation to other compounds (e.g. Gly), which was not examined in this work. The conversion of glyphosate to AMPA by EcAKR4-1 enzyme is time- (Fig. 4B) and glyphosate concentration-dependent (Fig. 5). The Km (glyphosate) was estimated to be 81 ± 4 μM, and the Vmax 4.79 ± 0.039 µmol mg−1 protein min−1, under our reaction conditions.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent glyphosate metabolism in mixtures of E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 and plant tissue extract. A, Glyphosate breakdown. B, Accumulation of glyphosate metabolites of AMPA. C, Accumulation of glyphosate metabolites of glyoxylate. Data are means ± se (n = 6).

Table 4. HPLC-Q-TOF-MS analyses of glyphosate metabolites produced by the action of E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 at different temperatures.

Data are means ± se (n = 6).

| Hours after Treatment | 25°C (µg mL−1) | 35°C (µg mL−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyphosate | AMPA | Glyoxylate | Glyphosate | AMPA | Glyoxylate | ||

| Controla | 1 | 241 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 245 (12.9) | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 249 (15.4) | 0 | 0 | 246 (9.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 238 (14.7) | 0 | 0 | 242 (10.3) | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 245 (4.0) | 0 | 0 | 244 (26.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Vector controlb | 1 | 235 (12.2) | 0 | 0 | 243 (2.1) | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 246 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 245 (17.6) | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 249 (12.9) | 0 | 0 | 237 (8.5) | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 248 (16.3) | 0 | 0 | 235 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| EcAKR4-1c | 1 | 164 (13.1) | 58.4 (5.8) | 13.6 (2.4) | 165 (8.0) | 84.3 (1.2) | 21.8 (1.3) |

| 3 | 89.6 (1.4) | 99.5 (2.9) | 37.6 (1.4) | 46.6 (3.1) | 187 (5.9) | 35.8 (1.8) | |

| 5 | 0 | 178 (7.0) | 56.9 (0.8) | 0 | 244 (1.8) | 60.0 (1.4) | |

| 7 | 0 | 177 (14.4) | 65.1 (1.0) | 0 | 237 (10.3) | 64.8 (3.0) | |

Glyphosate was mixed with plant tissue extract.

Bacterial-expressed vector control BSA protein was mixed with glyphosate and plant tissue extract.

Bacterial-expressed EcAKR4-1 protein was mixed with glyphosate and plant tissue extract.

Figure 5.

Concentration-dependent accumulation of AMPA in response to increased glyphosate concentrations in the mixture of E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1 enzyme and plant tissue extract. Data are means ± se (n = 6).

In Vivo Glyphosate Metabolism by E. colona Plants

Glyphosate metabolism in above-ground tissue of GR and S E. colona plants was analyzed using high resolution UPLC-MS/MS at 48 and 72 h after foliar application of glyphosate at a rate of 67.5 g ha−1 (one-eighth of the field recommended rate), to avoid damage to the S plants. Results showed that the glyphosate level decreased and AMPA/glyoxylate increased with time in both GR and S plants (Table 5). However, GR plants metabolized glyphosate to AMPA more rapidly than did the S plants. For example, at 72 h after glyphosate treatment, a glyphosate/AMPA of 1:4.8 and 1:0.44 as detected in GR and S plants, respectively, giving an 11-fold difference.

Table 5. UPLC-MS/MS analyses of glyphosate metabolites in GR versus S populations of E. colona.

The 3- to 4-leaf stage plants were treated with glyphosate at 67.5 g ha−1. Data are means ± se (n = 8).

| Time Point | Population | Glyphosate (µg g−1) | AMPA (µg g−1) | Glyoxylate (µg g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | S | 0 | 0 | 2.0 (0.2) |

| GR | 0 | 0 | 1.2 (0.1) | |

| 48 h | S | 44.4 (3.9) | 8.8 (1.3) | 8.8 (1.0) |

| GR | 34.6 (4.2) | 20.6 (2.7) | 15.4 (1.4) | |

| 72 h | S | 37.9 (3.6) | 16.6 (0.9) | 13.5 (1.3) |

| GR | 9.0 (1.7) | 43.3 (1.8) | 32.7 (3.1) |

3D Modeling Reveals Structural Interactions of EcAKR4-1 and Glyphosate

Structural modeling predicts that glyphosate interacts with EcAKR4-1 in the area involving amino acid residues Trp-21, Tyr-49, Lys-78, and Trp-112, as well as pyridine nucleotide (NADPH/NADP+) molecules bound to EcAKR4-1. The predicted glyphosate binding on the EcAKR4-1 surface potentially takes at least two types of conformation (Fig. 6, A and B). In the Type 1 conformation, glyphosate directly contacts residues Trp-21, Tyr-49, Lys-78, and Trp-112, forming attractive charge interactions with the side-chain amino groups of Lys-78, including one conventional H-bond with the Tyr-49 hydroxyl group, two conventional H-bonds with the side chain of Trp-112, and up to six Pi interactions (two Pi-cations and four Pi-anions) with the indole of Trp-21 (Fig. 6, A and B). Glyphosate also forms Pi anion interactions with the NADP pyridine group (Fig. 6C). This type of glyphosate binding by EcAKR4-1 is not time-stable, and there was a tendency for glyphosate to be released from the EcAKR4-1 active site over the first 30 nanoseconds of molecular dynamics (MD) as glyphosate-EcAKR4-1 interaction energy rose over the studied MD interval from −138.12 kJ mol−1 to 0. This, however, is not critical because such a time interval is more than sufficient for glyphosate to be involved in the reaction.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional modeling reveals structural interactions of EcAKR4-1 and glyphosate. General view of EcAKR4-1 with bound NADP+ (stick representation colored in green) and glyphosate (ball-and-stick representation) in type 1 conformation (A) and type 2 conformation (B). C, Spatial structure of contact interface between glyphosate and EcAKR4-1 in the type 1 conformation (left, NADP molecule is not present) and 2D-diagram (right) of intermolecular interactions. The protein contact surface is colored by H-bond donor/acceptor distribution; binding site amino acids are represented by sticks, and intermolecular contacts are indicated by dotted lines. D, Spatial structure of the contact interface between glyphosate and EcAKR4-1 in the type 2 conformation (left, NADP molecule is not present) and 2D-diagram of intermolecular interactions (right). The protein contact surface is colored by H-bond donor/acceptor distribution; binding site amino acids are represented by sticks, and intermolecular contacts are indicated by dotted lines. E, Partially presented relative spatial orientation of glyphosate (right) and NADP+ (left). The distance between the transferable hydrogen and target carbon in the NADP composition is shown by a red line.

In the Type 2 conformation, glyphosate immediately contacts residues Trp-21, Tyr-49, His-111, and Trp-112 as well as NADP (Fig. 6D). In this case, glyphosate forms two conventional H-bonds with Trp-112, one with His-111 and one with Tyr-49, and two Pi cation and two Pi anion interactions with Trp-21. In this conformation the van der Waals contact between glyphosate carbon-bound hydrogen and NADP pyridine was also observed (Fig. 6, D and E). This contact is very important as the hydrogen (in fact, a hydride ion, H−) is potentially able to be transferred to pyridine and, thus, reduce NADP+ to NADPH. In contrast to the Type 1 conformation, the EcAKR4-1:NADP+:glyphosate complex of the Type 2 conformation is time-stable over the 100-ns MD interval. Glyphosate-EcAKR4-1 interaction energy in this case stabilized at the level of −212.682 kJ mol−1 and, thus, the Type 2 glyphosate-EcAKR4-1 interaction is more likely than the Type 1. The complexes of NADPH and NADP+ with EcAKR4-1 were also highly stable, did not dissociate during the 100-ns period of MD, and had appropriate values of interaction energy (−832.12 and −875.46 kJ mol−1, respectively).

Metabolomic Analysis of Transgenic Rice Indicates a Possible Pathway for EcAKR4-1-Mediated Glyphosate Metabolism

Metabolomic analysis was performed with and without glyphosate treatment of the transgenic rice plants. Possible glyphosate metabolites (AMPA, glyoxylate, sarcosine, and formaldehyde) and the metabolic pathways involving these compounds were the main focus of the analysis. Although glyphosate and glyoxylate were not detected in the metabolome, the level of AMPA was significantly higher in glyphosate-treated EcAKR4-1 overexpressing (EcAKR4-1-T) versus glyphosate-treated GFP-overexpressing (GFP-T) rice plants, and in EcAKR4-1-T versus untreated (EcAKR4-1-C) rice plants (Table 6), confirming an increased capacity of EcAKR4-1-overexpressing rice plants to metabolize glyphosate. In addition, the level of Gly was greater in EcAKR4-1-T versus GFP-T and versus EcAKR4-1-C samples (Table 6), but lower in GFP-T versus untreated GFP-overexpressing (GFP-C) and EcAKR4-1-C versus GFP-C samples. Interestingly, it was also found that the level of cinnamaldehyde and cinnamyl alcohol showed an opposite trend among glyphosate-treated/untreated EcAKR4-1- and GFP-overexpressing rice samples. When an increase in the level of cinnamyl alcohol was observed in EcAKR4-1-T samples relative to GFP-T and EcAKR4-1-C samples, a corresponding decrease in cinnamaldehyde was detected (Table 6). This indicates that an enhanced level of cinnamaldehyde/cinnamyl alcohol is likely associated with EcAKR4-1 overexpression in rice plants.

Table 6. Changes in abundance of relevant metabolites identified by partial least-square discriminant analysis and significance analysis.

Significance of Tukey’s test is indicated by *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. C, control; T, glyphosate-treated.

| Metabolites | EcAKR4-1-C/GFP-C | EcAKR4-1-T/EcAKR4-1-C | GFP-T/GFP-C | EcAKR4-1-T/GFP-T | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold Change | P | Fold Change | P | Fold Changea | P | Fold Changea | P | |

| AMPA | 1 | — | 2.7* | 0.020 | 1 | — | 3.7** | 0.003 |

| Cinnamaldehyde | 1 | — | −3.1* | 0.037 | 1 | — | −3.3* | 0.013 |

| Cinnamyl alcohol | 1 | — | 3.1** | 0.005 | −3.0** | 0.008 | 3.3** | 0.001 |

| Gly | −3.6** | 0.001 | 3.1** | 0.005 | −3.0** | 0.005 | 2.7* | 0.023 |

| 2-oxoglutarate | 1 | — | 3.7* | 0.029 | 6.7* | 0.045 | 2.8** | 0.004 |

| l-Glu | 1 | — | −2.9** | 0.010 | 1 | — | −3.8* | 0.013 |

Fold change of “1” indicates no change; negative values indicate downregulation.

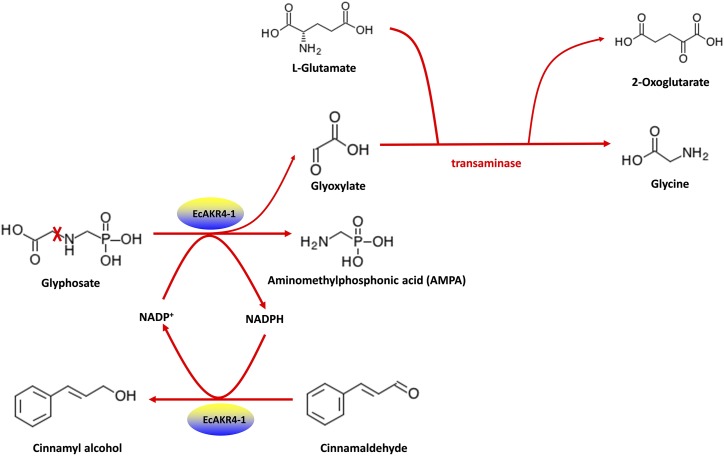

Metabolites with significant changes among comparisons were mapped to the reference canonical pathway in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. The most attractive Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes reaction is R00372 (Gly:2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase), converting glyoxylate to Gly. Glyoxylate, Gly, 2-oxoglutarate, and l-Glu are four compounds involved in the reaction. In fact, when a marginal increase in the abundance of 2-oxoglutarate was observed in EcAKR4-1-T relative to EcAKR4-1-C and GFP-T samples, a decrease in l-Glu was detected (Table 6), suggesting that the glyphosate metabolite glyoxylate is further metabolized to Gly, likely coupled with l-Glu oxidation to 2-oxoglutarate in transgenic rice overexpressing EcAKR4-1. In fact, an increase in the Gly pool was only evident in glyphosate-treated EcAKR4-1-overexpressing samples (Table 6). All these results helped facilitate a hypothesis for an EcAKR4-1-catalyzed glyphosate metabolism pathway in plants (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed metabolic pathway demonstrating the dual oxidase/reductase activity of ECAKR4-1 involved in glyphosate metabolism in E. colona. Glyphosate is oxidized to AMPA by EcAKR4-1 using NADP+ as a cofactor, and meanwhile cinnamaldehyde is reduced to cinnamyl alcohol, regenerating NADP+. Glyoxylate produced by glyphosate oxidation is further converted to Gly by transaminase coupled with l-Glu oxidation to 2-oxoglutarate. “X” indicates cleavage of the C-N bond in the glyphosate molecule. Please note that our structural modeling (Fig. 6), in vitro glyphosate metabolism by E. coli–expressed EcAKR4-1 (Table 3), and metabolomics of EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice (Table 6) are consistent with the proposed step for glyphosate conversion to AMPA. Further conversion of glyoxylate to Gly was only based on the metabolomic analysis of EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice (Table 6). Nevertheless, further experimental validation is needed for the proposed pathway.

DISCUSSION

Revealing the molecular basis of non-target–site herbicide resistance mechanisms is challenging as it may involve superfamilies of metabolic enzymes and transporters (Délye et al., 2013) and requires multiple analytical approaches. Here, combining transcriptomic, transgenic, and metabolomic approaches, we reveal that glyphosate metabolism (to AMPA) via an upregulated plant AKR (EcAKR4-1) is involved in conferring glyphosate resistance in a GR E. colona population. However, how the AKR expression and activity in the GR E. colona plants (Table 2) are upregulated remains to be elucidated. We speculate that it may be related to SNPs in the 5′-UTR region (Supplemental Fig. S3), and post-translational modifications of the AKR, as two of the key residues (Tyr-49 and Lys-78) interacting with glyphosate (Fig. 6C) are located relatively close to the N terminus and are well known to display post-translational modifications (e.g. phosphorylation). Future work including promotor analysis and copy number variation of the AKR gene may provide more information on AKR gene expression regulation. And purification of the native AKR enzyme could reveal post-translational modifications.

To establish if EcAKR4-1 endows glyphosate resistance due to its ability to metabolize glyphosate, studies were conducted on E. coli-expressed EcAKR4-1. HPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis revealed that EcAKR4-1 catalyzes glyphosate conversion to the much less toxic compound AMPA (and glyoxylate) in a time-, concentration-, and temperature-dependent manner (Table 4; Figs. 3, 4, and 6). The estimated Km (glyphosate) value of EcAKR4-1 (81 ± 4 μm) was close to that determined with Arabidopsis AKR4C8 (64 ± 15 μM) and AKR4C9 (27.8 ± 13.6 μm) for oxidation of the substrate 5-dihydro-testosterone (Simpson et al., 2009). The bacterial GOX (YP_001369824.1) and GO (CP011882.1) were reported to convert glyphosate into AMPA and glyoxylate (Barry and Kishore, 1995; Pedotti et al., 2009). However, the EcAKR4-1 that we identified in this study showed only 23.5% homology to GOX and 27.7% to GO, indicating that EcAKR4-1 might be a novel plant GOX-like enzyme. Indeed, consistent with the metabolomics analysis of glyphosate metabolism in AKR transgenic rice (Table 6), analysis of glyphosate metabolism in GR versus S E. colona plants demonstrated that GR plants have greater capacity to convert glyphosate to AMPA and glyoxylate than the S plants (Table 5). AMPA is much less phytotoxic than glyphosate (Nandula et al., 2007; Duke, 2011), but still has some herbicidal activity, and therefore plants possessing only the ability to metabolize glyphosate to AMPA have not completely detoxified glyphosate. Although the other glyphosate metabolite, glyoxylate (also an endogenous metabolite in plant photorespiration), is known to be inhibitory to ribulose-1-5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Lu et al., 2014), it may be detoxified to glycolate by glyoxylate reductase, and to Gly by Gly: 2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase as observed in EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice (see results on metabolomics in "Metabolomic Analysis of Transgenic Rice Indicates a Possible Pathway for EcAKR4-1-Mediated Glyphosate Metabolism"). Genetic inheritance of glyphosate resistance in this particular GR E. colona population has not been investigated yet. However, non-target–site herbicide resistance can be a polygenic (quantitative) trait (Duhoux et al., 2015). Based on our preliminary studies, an additional resistance mechanism (e.g. ABC transporters) may sequester glyphosate/AMPA away from the target enzyme EPSPS in the cytoplasm.

To explore the structural basis of AKR-catalyzed conversion of glyphosate, we employed 3D modeling of EcAKR4-1. This protein belongs to the NADP-dependent AKR family, which usually uses NADPH as an electron source for substrate reduction (Penning, 2015). However, one NADPH molecule is able to donate only two electrons (one hydride anion, H−). To reduce the carboxyl group of glyphosate to an alcohol, at least four electrons (two hydride anions) are necessary. EcAKR4-1 is able to bind only one NADPH molecule, and exchange of NADP+/NADPH molecules during the reaction cycle is practically impossible because the nucleotide is more deeply buried in the protein space than glyphosate. To bind the second NADPH molecule, the EcAKR4-1 would have to release the incompletely processed substrate. Hence, glyphosate reduction by EcAKR4-1 using NADPH as a cofactor may be structurally unlikely to occur. Rather, glyphosate oxidation by EcAKR4-1 may be possible, similar to the known mechanism of GOX or GO by soil micro-organisms (Pollegioni et al., 2011). In fact, the ability of plant AKRs to oxidize several substrates has been demonstrated (Kavanagh et al., 2002; Simpson et al., 2009; de Sousa et al., 2009). Among other possibilities, the oxidized form of NADP (NADP+) is an acceptable substitute. This is supported by the fact that addition of NADP+ rather than NADPH in the in vitro reaction greatly enhanced glyphosate conversion to AMPA (Table 3). As EcAKR4-1 also displayed a typical AKR activity reducing the substrate methylglyoxal, it may have a dual redox function (e.g. reducing the substrate of some aldehydes/ketones and oxidizing the substrate like glyphosate), although with much higher reducing than oxidizing activity (88.5 ± 9.6 versus 4.79 ± 0.039 μmol mg−1 protein min−1, respectively). The presence of two substrates (i.e. glyphosate and an aldehyde/ketone) or other unknown components or cofactors would accelerate the change of NADP state from NADP+ to NADPH and vice versa, and, as a result, increase the productivity of the reactions. This was realized by a dramatic increase in AMPA production upon addition to the reaction mixture of plant tissue extracts that may contain these compounds (Figs. 3 and 4; Table 3). The cofactors/substrates in plant tissue extract that putatively enhance AKR activity need further investigation.

To understand possible pathways for EcAKR4-1 mediated glyphosate metabolism, a metabolomic analysis of EcAKR4-1 transgenic rice was performed. The most relevant changes in metabolite abundance were a significant increase in 2-oxoglutarate and cinnamyl alcohol and a decrease in l-Glu and cinnamaldehyde in glyphosate-treated EcAKR4-1 (EcAKR4-1-T) plants (Table 6). This coincided with an increased level of the glyphosate metabolites AMPA and Gly in these plants, suggesting that the reduction of cinnamaldehyde to cinnamyl alcohol could be coupled with glyphosate oxidation to AMPA, and oxidation of l-Glu to 2-oxoglutarate linked with glyoxylate conversion to Gly. Thus, we propose a hypothetical metabolic pathway that EcAKR4-1 works as a dual oxidase/reductase in a cycle catalyzing glyphosate oxidation and cinnamaldehyde reduction using the same NADP molecule as both an acceptor and a donor of electrons (Fig. 7). Although our data (Tables 3 and 6; Fig. 6) are consistent with this hypothetical model, further experimental validation is needed.

Glyphosate is rarely metabolized by plants. However, all possible resistance mechanisms, including rare mechanisms, are selected by persistent glyphosate selection pressure on huge weed populations across vast areas. GOX-like plant enzymes have been long suspected to evolve in response to glyphosate selection, but have received little attention (Duke, 2011). In this study, we demonstrate that increased expression of an AKR gene (EcAKR4-1) has been selected by intensive glyphosate use and endows this E. colona population with an enhanced capacity to metabolize and thus resist glyphosate. Our findings will open a new avenue for studies on metabolic herbicide resistance, additional to P450- and GST-mediated herbicide metabolism (Powles and Yu, 2010; Yu and Powles, 2014). It is worthwhile to examine the potential evolution of AKR-mediated metabolic resistance to glyphosate (and other herbicides) in other herbicide-resistant weedy plant species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

To minimize genetic variability, the initially bulked GR (Rbulk) and susceptible (Sbulk) lines were obtained from within a single GR Echinochloa colona population by vegetative plant cloning plus glyphosate treatment (Goh et al., 2016). We established that glyphosate resistance in this Rbulk line is non-target-site–based (Goh et al., 2018). Single R (Rsingle) and S (Ssingle) lines were then generated respectively from the initial Rbulk and Sbulk lines for this study (Fig. 1; Goh et al., 2018). This process further minimized genetic variability between the GR and S E. colona lines for RNA-seq analysis. In addition, as the Rbulk and Rsingle lines are still segregating for glyphosate resistance at 2× the recommended field rate of 1,080 g glyphosate ha−1 (resistance/susceptibility 22:3), this allows for further isolation of GR and S individuals (Rbulk-R/S, Rsingle-R/S) from within each of these two R lines for contig expression validation (Fig. 1). Furthermore, plants from two additional glyphosate-susceptible E. colona populations (QBG1 and Crossy) from north-east Australia were also included for contig expression analysis.

The GR and S individuals were determined by glyphosate treatment. Briefly, GR and S seedlings were grown in pots in a controlled environment room with day/night temperature of 35/30°C and light flux of 350 μmol m−2 s−1 at 75% humidity. At the 1–2-tiller stage, the above-ground (1 cm) shoot and leaf material of individual plants were removed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Three d later, the GR seedlings were treated with 1,080 g of glyphosate ha−1 and the S seedlings with 270 g of glyphosate ha−1. Glyphosate was applied using a laboratory spray cabinet with a two-nozzle boom delivering 118 L ha−1 water at a pressure of 210 kPa and a speed of 1 m s−1. Plant survival was determined two weeks after treatment, and the most GR and S individuals were identified and the corresponding preharvested frozen shoot material was used for RNA-seq.

RNA-Seq Data Analysis and AKR Gene Expression Validation

Detailed descriptions of the RNA-seq data analysis, PCR validation of the AKR gene expression in RNA-seq samples, and samples from multiple GR and S populations/lines and under different temperatures, are provided in Supplemental Material and Methods.

Full Sequence Cloning and Analysis of the AKR Genes

Based on Echinochloa crus-galli genome sequences, one primer pair, EcAKR-F (5′-CTTCCTAAAGTTCACCGTCCCA-3′)/EcAKR-R (5′-CCACCACCACTGCTTCCCT-3′), was designed from the UTR for cloning the full-length cDNA sequences of E. colona AKR genes. PCR was conducted in a 25-μL volume, consisting of 1 μL of cDNA, 0.5 mm of each primer, and 12.5 μL of PrimeSTAR MAX (Takara). PCR was run in a Mastercycler (AB Instruments) with the following profile: 98°C 10 s, 40 cycles of 98°C 10 s, 56°C 15 s, and 72°C 90 s, followed by a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. The amplified cDNA fragments were purified from agarose gels using the Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega). The amplified cDNA fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and transformed into Escherichia coli-competent cells (strain JM109). The chromatogram files of all sequences were visually checked, and sequences were aligned using the software DNAMAN 6.0 (https://www.lynnon.com/).

5′-RACE and 3′-RACE were conducted to clone the UTR region of the EcAKR4-1 gene from plants of the GR and three S E. colona populations using the SMART RACE kit (Takara) with gene-specific primers of EcAKR-51/EcAKR-52 for 5′-RACE and EcAKR-31/EcAKR-32 for 3′-RACE (Supplemental Table S2).

Measurement of AKR Activity in E. colona

AKR activities in plants of Rbulk, Rsingle, Sbulk, Ssingle, and two other S E. colona populations (QBG1 and Crossy) were determined using a commercial kit (Zhenao) with methylglyoxal as a substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. AKR was extracted by grinding 0.4 g of leaf material in liquid nitrogen with 400 μL of isolation buffer, followed by centrifugation at 13,000g for 10 min. The reaction mixture contained 0.1 m of sodium P buffer (pH 7), 0.1 mm of NADPH/NADH, 2 mm of methylglyoxal, and 400 μL of leaf extract (3.6 mg of protein). AKR activity was quantified by measuring the decrease in NADPH concentration at 340 nm over 3 min using a model no. UV-160 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) at 25°C.

Rice Calli Transformation and Growth Response to Glyphosate

To express EcAKR4-1 in rice calli, expression cassettes were constructed as described in Supplemental Figure S6. The vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens by electroporation and the transformed A. tumefaciens strains were used to transform wild-type Nipponbare rice. All constructed vectors were checked carefully by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing before rice transformation.

Rice transformation was carried out using the procedures as described in Toki et al. (2006), with modifications. The introduction of the transgene into rice calli was confirmed by PCR using the primer pair HygF1 (5′-GACCTGCCTGAAACCGAACTG-3′)/HygR1 (5′-CCCAAGCTGCATCATCGAAA-3′), which amplifies the HPT gene in the vector. Hygromycin-resistant rice calli were selected, and subcultured in Nutrient Broth plates (with hygromycin), and proliferating calli transferred onto fresh Nutrient Broth plates containing glyphosate at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 mm (stock solution prepared in water). Glyphosate concentrations at ≥0.5 mm inhibited growth of the GFP-transgenic rice calli (used as a negative control). For each glyphosate concentration, 10 transformed calli were used and two independent transformation experiments were conducted. After two weeks in the dark, the growth response to glyphosate was compared between calli transformed with the GFP or the EcAKR4-1 gene. In addition, the response of transgenic calli to the nonselective herbicide glufosinate was also tested at concentrations of 0, 10, 40, 80, and 120 μm.

Glyphosate Sensitivity of Transgenic Rice Seedlings

Transgenic rice (Oryza sativa) calli (GFP and EcAKR4-1 overexpressing lines) were regenerated and T0 plantlets ranging from 3 to 5 cm in length were transferred to rooting medium supplemented with hygromycin. After 7 d of acclimatization, the T0 seedlings were transferred to a mixture of fertilized soil and perlite (2:1, v/v) for subsequent molecular analysis and glyphosate resistance testing.

Seedlings were screened first by PCR using the specific primer pair HygF1/HygR1 for the vector HPT gene. For further detection of the target transgene, two primer pairs were designed: A1 (5′-AAAGAAATTGGGTGACTTG-3′) and A2 (5′-CTTGTAAACGCTCTGTGG-3′) amplifying a 427-bp fragment of transformed EcAKR4-1, and B1 (5′-TTGTCCCAGTTCTCATTG-3′) and B2 (5′-GTATCTTGCGAAACATCTAA-3′) amplifying a 373-bp fragment of transformed GFP. EcAKR4-1 gene expression and total AKR activity were quantified as described in "Measurement of AKR Activity in E. colona" and the Supplemental Material and Methods. The seedlings were grown in a controlled growth cabinet with an average day/night temperature of 30°C/25°C and a 14-h photoperiod under a light intensity of 180 μmol m−2 s−1. T0 seedlings of 12 lines were then foliar-treated with glyphosate at 0, 540, 1,080, and 2,160 g ha−1 (corresponding to 0, 1×, 2×, and 4× the recommended field rate), respectively, and T1 seedlings of 5 lines were treated at 540 g ha−1. Glyphosate was applied using a 3WP-2000 hand-held system (Zhongnongjidian), equipped with a 390-mL min−1 flow nozzle at a pressure of 3.0 kg cm−2. Plant survival and mortality was determined three weeks after treatment.

EcAKR4-1 Gene Expression in E. coli and In Vitro Glyphosate Metabolism Assay

To determine if the EcAKR4-1 gene product can metabolize glyphosate, the EcAKR4-1 gene was expressed with a hexa-His tag in E. coli using the expression system pET32a. The His-tagged EcAKR4-1 enzyme was purified using the MagneHis Protein Purification System (Promega). Cells were lysed directly in the culture medium using the provided FastBreak Cell Lysis Reagent. His-tagged EcAKR4-1 enzyme was purified under native conditions. The protein was dissolved with the lysis buffer (FastBreak Cell Lysis Reagent, pH 7.4) and quantified using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976).

This purified enzyme was used for glyphosate metabolism studies. The reaction mixture (3 mL, pH 6.8) was 9 μg of EcAKR4-1 enzyme, 1.48 mm of glyphosate (prepared in water), and 0.3 mL of aqueous plant tissue extract (20 g E. colona plant material in 500 mL of water, extracted in boiling water for 10 min and filtered) to supplement any unknown factors (e.g. cofactors) for the AKR enzyme reaction. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1, 3, 5, and 7 h at 25°C and 35°C, respectively. HPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis (see "HPLC-Q-TOF-MS Analysis of Glyphosate Metabolites by E. coli-Expressed EcAKR4-1 Enzyme") was performed to detect reaction products at each time point. Mixtures of glyphosate and plant tissue extract without AKR enzyme served as the control. In addition, a mixture of E. coli-expressed His-tagged bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein, glyphosate, and plant tissue extract was used as a vector control.

To estimate AKR Km and Vmax for glyphosate, EcAKR4-1 enzyme (20 μg) and glyphosate at 1, 10, 100, 500, 1,000, 1,500 and 2,000 μm were used. The reactions were incubated at 35°C for 30 min and AMPA production was measured using HPLC-Q-TOF-MS. The Km value was calculated by fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation ν = VS/(Km + S). Each assay contained two technical replicates and the assay was repeated three times with similar results, and data were pooled for analysis.

HPLC-Q-TOF-MS Analysis of Glyphosate Metabolites by E. coli-Expressed EcAKR4-1 Enzyme

Chromatographic separations of glyphosate and its possible metabolites (AMPA, glyoxylate, sarcosine, and formaldehyde) were achieved with the 1290 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) on a XAqua C18 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, particle size 5 μm; Acchrom). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (FA) aqueous solution (solvent A) and acetonitrile (ACN; solvent B) with a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1 and an injection volume of 5 μL. The gradient was set as 0–5 min with an isocratic elution of 10% (v/v) solvent B.

Mass spectral analysis was carried out using a model no. 6530 QqTOF Mass Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). The eluent from the HPLC was directed into the mass spectrometer through an electrospray ionization interface and data were acquired in full scan mode (m/z: 20–1,000 D). Glyphosate and AMPA data acquisition were performed in positive ionization, and glyoxylate in negative ionization mode. Parameters of the ion source were: gas temperature 345°C, gas flow 10 L min−1, nebulizer 40 psi, sheath gas temperature 350°C, sheath gas flow 11 L min−1, vcap voltage 4,000 V, nozzle voltage 500 V, and fragment voltage 135 V. Accurate mass measurements of each peak from the total ion chromatogram were obtained using an automated calibration to provide the mass correction. Purine (C5H4N4, m/z: 121.0508; Agilent Technologies) and HP-0921 (C18H18O6N3P3F24, m/z: 922.0097; Agilent Technologies) were used for mass calibration. Monoisotopic masses of the protonated molecular ions [M+H]+ were calculated using the data explorer software of the Q-TOF instrument. HPLC-Q-TOF-MS data were processed using the “Masshunter Qualitative Analysis” (B.05.00; Agilent Technologies). The calibration equations were established from known concentrations of analytical grade of glyphosate and its metabolites, which were determined from their peak areas in the electropherogram. The experiment had three replicates and was repeated with similar results, and all data were pooled for analysis.

UPLC-MS/MS Analysis of Glyphosate Metabolites by GR and S E. colona Plants

GR and S E. colona plants were grown under the same conditions as for transgenic rice plants. At the 3- to 4-leaf stage they were treated with glyphosate at 67.5 g ha−1, using the 3WP-2000 hand-held system. Above-ground tissue samples were collected 48 h and 72 h after treatment, and unabsorbed glyphosate was removed by rinsing the samples in 100 mL of DL water and blotting dry. After extraction with water under ultrasonication, the sample was defatted with dichloromethane and purified on a C18 solid phase extraction cartridge, and then glyphosate, AMPA, and glyoxylate were derivatized using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl in borate buffer for 2 h. The derivatives of glyphosate, AMPA, and glyoxylate were separated by gradient elution on a UPLC BEH C18 column (Waters) with the mobile phase of 2 mmol L−1 of ammonium acetate and ACN, and detected by positive electrospray ionization-MS in “multiple reaction monitoring” mode. The derivatives of glyphosate, AMPA, and glyoxylate were used as standards for sample quantification. The experiment was conducted with eight biological replicates per harvest and each replicate sample consisted of five plants. Other possible glyphosate metabolites (e.g. sarcosine and formaldehyde) were not analyzed.

Structural Modeling of EcAKR4-1

The spatial structure of E. colona AKR was reconstructed based on the EcAKR4-1 sequence by a homology modeling approach (Venselaar et al., 2010) using the web service “SWISS-MODEL” (Waterhouse et al., 2018). The 1.00 Å resolution crystal structure of Homo sapiens aldose reductase in complex with NADP (Protein Data Bank ID 2AGT) and 1.45 Å resolution crystal structure of AKR4C7 from maize (Zea mays; PDB ID 5JH1) were used as templates for EcAKR4-1 reconstruction based on the highest scores among all possible structural templates. Computational details are according to procedures described in Chu et al. (2018) and in Supplemental Material and Methods.

Metabolomics Analysis of Transgenic Rice Seedlings

The experimental design for metabolomic analysis included eight biological replicates of transgenic rice seedlings overexpressing EcAKR4-1 or GFP, with and without glyphosate treatment at 270 g ha−1. Leaf samples of untreated controls were collected at time point 0, and glyphosate-treated samples were collected 24 h after treatment. The leaf samples were homogenized in 80% methanol and 0.1% (v/v) FA, vortexed and sonicated for 10 min and stored at −20°C for 1 h before overtaxing at room temperature and centrifugation at 18,407 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant (1 mL) was filtered through a 0.22-μm organic phase filter into a glass vial before use. An Accucore HILIC column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for liquid chromatography, at 40°C and a flow rate of 3 mL min−1. In positive phase liquid chromatography, the mobile phase A was 95% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% FA, and B was 50% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% FA. In negative phase liquid chromatography, A was 95% ACN (pH 9.0), and the mobile phase B was 50% ACN (pH 9.0). The gradient was: 98% A:2% B for 1 min, a linear gradient to 50% A:50% B over 17.5 min, and 2 min isocratic before going back to the initial LC conditions in 20 min. Ten μL of each sample were injected and a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1 was used throughout the LC runs. Metabolites were quantified by normalization to the internal standards. Other technical details, and data analysis, are provided in Supplemental Material and Methods.

Accession Numbers

The EcAKR4-1 and EcAKR4-2 sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos: MK592097 and MK592098). The RNA-seq data included in this study were deposited into National Genomics Data Center, Beijing Institute of Genomics (http://bigd.big.ac.cn) under accession number PRJCA001826.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Somatic chromosome counting of E. colona (4n = 36) using root tip samples.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phylogenetic analysis of EcAKR4-1 and EcAKR4-2 and their relationships with other plant AKRs.

Supplemental Figure S3. Sequence comparison of the amplified fragments of (a) the 3′ UTR and (b) the 5′UTR from E. colona plants of the GR, S, and two additional S populations (QBG1 and Crossy).

Supplemental Figure S4. Growth of rice calli transformed with the GFP or EcAKR4-1 genes in medium containing glufosinate.

Supplemental Figure S5. SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant EcAKR4-1 enzyme purified from E. coli.

Supplemental Figure S6. Vector construct for overexpression of EcAKR4-1 in rice callus.

Supplemental Table S1. Identification of differentially expressed AKR and EPSPS contigs in GR versus S populations of E. colona using RNA-seq.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used for RT-qPCR relative quantification of gene expression and UTR cloning.

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Materials and Methods with DNA-seq data analysis and AKR gene expression validation, structural modeling of EcAKR4-1, and metabolomic analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Sou Sheng Goh for his initial characterization of this GR E. colona population, and Dr. Danica Goggin for proofreading of the article.

Footnotes

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901905), the Australian Grains Research and Development Corporation, China Agriculture Research System (CARS-16-E19), the Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation (LZ17C130001), the Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production (111 Project B17039), and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (award TG-DMR 110088).

References

- Agrawal C, Sen S, Yadav S, Rai S, Rai LC (2015) A novel aldo-keto reductase (AKR17A1) of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 degrades the rice field herbicide butachlor and confers tolerance to abiotic stresses in E. coli. PLoS One 10: e0137744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerson SR, Rodriguez DJ, Tran M, Feng Y, Biest NA, Dill GM (2002) Glyphosate-resistant goosegrass. Identification of a mutation in the target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase. Plant Physiol 129: 1265–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KA, McBride MB (2005) Oxidative degradation of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonate by manganese oxide. Environ Sci Technol 39: 9223–9228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry GF, Kishore GM (1995) Glyphosate tolerant plants. United States Patent Application No. US5463175A.

- Barski OA, Tipparaju SM, Bhatnagar A (2008) The aldo-keto reductase superfamily and its role in drug metabolism and detoxification. Drug Metab Rev 40: 553–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MMA. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Chen J, Nyporko A, Han H, Yu Q, Powles S (2018) Novel α-tubulin mutations conferring resistance to dinitroaniline herbicides in Lolium rigidum. Front Plant Sci 9: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho LB, Alves PL, González-Torralva F, Cruz-Hipolito HE, Rojano-Delgado AM, De Prado R, Gil-Humanes J, Barro F, de Castro MD (2012) Pool of resistance mechanisms to glyphosate in Digitaria insularis. J Agric Food Chem 60: 615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Délye C, Jasieniuk M, Le Corre V (2013) Deciphering the evolution of herbicide resistance in weeds. Trends Genet 29: 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa SM, Rosselli LK, Kiyota E, da Silva JC, Souza GHMF, Peroni LA, Stach-Machado DR, Eberlin MN, Souza AP, Koch KE, et al. (2009) Structural and kinetic characterization of a maize aldose reductase. Plant Physiol Biochem 47: 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhoux A, Carrère S, Gouzy J, Bonin L, Délye C (2015) RNA-seq analysis of rye-grass transcriptomic response to an herbicide inhibiting acetolactate-synthase identifies transcripts linked to non-target-site-based resistance. Plant Mol Biol 87: 473–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke SO. (2011) Glyphosate degradation in glyphosate-resistant and -susceptible crops and weeds. J Agric Food Chem 59: 5835–5841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke SO, Powles SB (2008) Glyphosate: A once-in-a-century herbicide. Pest Manag Sci 64: 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke SO, Powles SB, Sammons RD (2018) Glyphosate: How it became a once in a hundred year herbicide and its future. Outlooks Pest Manag 29: 247–251 [Google Scholar]

- Gaines TA, Cripps A, Powles SB (2012) Evolved resistance to glyphosate in Junglerice (Echinochloa colona) from the tropical ord river region in Australia. Weed Technol 26: 480–484 [Google Scholar]

- Gaines TA, Patterson EL, Neve P (2019) Molecular mechanisms of adaptive evolution revealed by global selection for glyphosate resistance. New Phytol 223: 1770–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines TA, Zhang W, Wang D, Bukun B, Chisholm ST, Shaner DL, Nissen SJ, Patzoldt WL, Tranel PJ, Culpepper AS, et al. (2010) Gene amplification confers glyphosate resistance in Amaranthus palmeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 1029–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, d’Avignon DA, Ackerman JJH, Sammons RD (2010) Rapid vacuolar sequestration: The horseweed glyphosate resistance mechanism. Pest Manag Sci 66: 345–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh SS, Vila-Aiub MM, Busi R, Powles SB (2016) Glyphosate resistance in Echinochloa colona: Phenotypic characterisation and quantification of selection intensity. Pest Manag Sci 72: 67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh SS, Yu Q, Han H, Vila-Aiub MM, Busi R, Powles SB (2018) Non-target-site glyphosate resistance in Echinochloa colona from Western Australia. Crop Prot 112: 257–263 [Google Scholar]

- González-Torralva F, Rojano-Delgado AM, Luque de Castro MD, Mülleder N, De Prado R (2012) Two non-target mechanisms are involved in glyphosate-resistant horseweed (Conyza canadensis L. Cronq.) biotypes. J Plant Physiol 169: 1673–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap I. (2019) International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Available at: http://www.weedscience.org (October 1, 2019)

- Kavanagh KL, Klimacek M, Nidetzky B, Wilson DK (2002) The structure of apo and holo forms of xylose reductase, a dimeric aldo-keto reductase from Candida tenuis. Biochemistry 41: 8785–8795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Peng Q, Han H, Nyporko A, Kulynych T, Yu Q, Powles S (2018) A novel EPSPS Thr-102-Ser substitution endows glyphosate resistance in Tridax procumbens. J Agric Food Chem 66: 7880–7888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorrainecolwill DF, Powles SB, Hawkes TR, Hollinshead PH, Warner SAJ (2002) Investigations into the mechanism of glyphosate resistance in Lolium rigidum. Pestic Biochem Physiol 74: 62–72 [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Li Y, Yang Q, Zhang Z, Chen Y, Zhang S, Peng X-X (2014) Suppression of glycolate oxidase causes glyoxylate accumulation that inhibits photosynthesis through deactivating Rubisco in rice. Physiol Plant 150: 463–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandula VK, Reddy KN, Rimando AM, Duke SO, Poston DH (2007) Glyphosate-resistant and -susceptible soybean (Glycine max) and canola (Brassica napus) dose response and metabolism relationships with glyphosate. J Agric Food Chem 55: 3540–3545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandula VK, Riechers DE, Ferhatoglu Y, Barrett M, Duke SO, Dayan FE, Goldberg-Cavalleri A, Tétard-Jones C, Wortley DJ, Onkokesung N, et al. (2019) Herbicide metabolism: Crop selectivity, bioactivation, weed resistance, and regulation. Weed Sci 67: 149–175 [Google Scholar]

- Patterson EL, Pettinga DJ, Ravet K, Neve P, Gaines TA (2018) Glyphosate resistance and EPSPS gene duplication: Convergent evolution in multiple plant species. J Hered 109: 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedotti M, Rosini E, Molla G, Moschetti T, Savino C, Vallone B, Pollegioni L (2009) Glyphosate resistance by engineering the flavoenzyme glycine oxidase. J Biol Chem 284: 36415–36423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning TM. (2015) The aldo-keto reductases (AKRs): Overview. Chem Biol Interact 234: 236–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perotti VE, Larran AS, Palmieri VE, Martinatto AK, Alvarez CE, Tuesca D, Permingeat HR (2019) A novel triple amino acid substitution in the EPSPS found in a high-level glyphosate-resistant Amaranthus hybridus population from Argentina. Pest Manag Sci 75: 1242–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzul L, Castillo M, Stenström J (2009) Degradation of glyphosate and other pesticides by ligninolytic enzymes. Biodegradation 20: 751–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollegioni L, Schonbrunn E, Siehl D (2011) Molecular basis of glyphosate resistance-different approaches through protein engineering. FEBS J 278: 2753–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles SB, Lorrainecolwill DF, Dellow JJ, Preston C (1998) Evolved resistance to glyphosate in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) in Australia. Weed Sci 46: 604–607 [Google Scholar]

- Powles SB, Yu Q (2010) Evolution in action: Plants resistant to herbicides. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 317–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratley J, Stanton R, Urwin N, Baines P, Hudson D, Dill G, Bishop AC, Boersma M, Barnes CD (1999) Resistance to glyphosate in Lolium rigidum. I. Bioevaluation. Weed Sci 47: 405–411 [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KN, Rimando AM, Duke SO, Nandula VK (2008) Aminomethylphosphonic acid accumulation in plant species treated with glyphosate. J Agric Food Chem 56: 2125–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons RD, Gaines TA (2014) Glyphosate resistance: State of knowledge. Pest Manag Sci 70: 1367–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PJ, Tantitadapitak C, Reed AM, Mather OC, Bunce CM, White SA, Ride JP (2009) Characterization of two novel aldo-keto reductases from Arabidopsis: Expression patterns, broad substrate specificity, and an open active-site structure suggest a role in toxicant metabolism following stress. J Mol Biol 392: 465–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H (2006) Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J 47: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemanna RS, Vennapusa AR, Easwaran M, Chandrashekar BK, Rao H, Ghanti K, Sudhakar C, Mysore KS, Makarla U (2017) Aldo-keto reductase enzymes detoxify glyphosate and improve herbicide resistance in plants. Plant Biotechnol J 15: 794–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venselaar H, Joosten RP, Vroling B, Baakman CAB, Hekkelman ML, Krieger E, Vriend G (2010) Homology modelling and spectroscopy, a never-ending love story. Eur Biophys J 39: 551–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, et al. (2018) SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 46(W1): W296–W303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Jalaludin A, Han H, Chen M, Sammons RD, Powles SB (2015) Evolution of a double amino acid substitution in the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase in Eleusine indica conferring high-level glyphosate resistance. Plant Physiol 167: 1440–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Powles S (2014) Metabolism-based herbicide resistance and cross-resistance in crop weeds: A threat to herbicide sustainability and global crop production. Plant Physiol 166: 1106–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]