Abstract

Background:

Relatively little is known about the frequency and factors associated with miscarriage among women living with HIV.

Objective:

To evaluate factors associated with miscarriage among women enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS).

Study design:

We conducted an analysis of longitudinal data collected from October 1, 1994 to September 30, 2017. Women who attended at least two WIHS visits and reported pregnancy during follow-up were included. Miscarriage was defined as spontaneous loss of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation based upon self-report assessed at biannual visits. We modeled the association between demographic, behavioral, and clinical covariates and miscarriage (versus live birth) for women overall and stratified by HIV status using mixed model logistic regression.

Results:

Similar proportions of women living with and at without HIV experienced miscarriage (37% and 39%, respectively, p=0.638). In adjusted analyses, smoking tobacco (adjusted odds ratio, aOR=2.0), alcohol use (aOR=4.0), and marijuana use (aOR=2.0) were associated with miscarriage. Among women living with HIV, low HIV viral load (<4 log10 copies/mL) (aOR=0.5) and protease inhibitor (PI) (aOR=0.4) versus non-use of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) use were protective against miscarriage.

Conclusions:

We did not find increased odds of miscarriage among women living with HIV compared to uninfected women, however poorly controlled HIV-infection was associated with increased miscarriage risk. Higher miscarriage risk among women exposed to tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana highlight potentially modifiable behaviors. Given previous concern about ART and adverse pregnancy outcomes, the novel protective association between PIs compared to non-cART and miscarriage in this study is reassuring.

Keywords: antiretroviral treatment, HIV, marijuana, miscarriage, Women’s Interagency HIV Study

INTRODUCTION

In the current combined antiretroviral treatment (cART) era, pregnancy rates have increased among US women with HIV and are comparable to women without HIV(1). Miscarriage occurs in an estimated 10-20% of US women(4-6). However, relatively little is known about the frequency and factors associated with miscarriage among women living with HIV (WLHIV).

Among the few cART era analyses, data are conflicting as to whether women with HIV experience an increased risk miscarriage; three studies from Africa reported increased risk(2-4) while one from the US did not(5). Most studies have focused on outcomes of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal morbidity(6-19), with fewer and more contradictory studies, mostly from sub-Saharan Africa, focused on miscarriage(2-5, 20-23).

Previous analyses from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), the largest ongoing multi-center prospective cohort study of HIV among women in the US, have explored factors associated with miscarriage. In the 1994-2002 WIHS cohort, Massad et al. found that miscarriage rates were similar for WLHIV and women without HIV, and that in WLHIV, miscarriage was associated with prior miscarriage, marijuana use, and non-ART use. That analysis did not consider the role of potential correlates including alcohol, frequency of marijuana use, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), specific cART regimens, or women without HIV(5). In the 1994-2012 WIHS cohort, Cates et al. found that HIV viral load during pregnancy predicted pregnancy loss(22), while Westreich et al. found cigarette smoking was associated with pregnancy loss in the 1994-2014 WIHS cohort(23). Neither of these studies reported on factors associated with miscarriage outside of viral load and smoking, respectively. To provide a more comprehensive and contemporary evaluation, we assessed the frequency and factors associated with miscarriage in both women living with and without HIV enrolled in WIHS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cohort.

We analyzed data collected between October 1, 1994 and September 30, 2017 from women enrolled in WIHS(24). This cohort is comprised of women living with and without HIV recruited from ten US sites. In 1994, enrollment began in six sites (Bronx, Brooklyn, Chicago, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco), and those sites re-enrolled during 2001-02 and 2011-12. The cohort was expanded in 2013-2015 to include four additional sites, to represent the southern United States (Atlanta, Chapel Hill, Miami, and Birmingham/Jackson). Enrollees were frequency matched on demographics and risk factors for acquiring HIV including drug use and number of sexual partners(24, 25). Medical and laboratory exams (including CD4 T-cell count and HIV viral load) as well as detailed interviews (collecting data including cART use, obstetric and gynecologic history, and medication use) are conducted longitudinally at semiannual visits by trained interviewers.

Ethics.

Each WIHS site and the data center provided Institutional Review Board approval prior to study enrollment. Enrollees provided written informed consent. All data used in this analysis were de-identified.

Outcome definition.

Women who attended at least two WIHS visits and self-reported a pregnancy during longitudinal follow-up were included in this analysis. Since prenatal care, delivery, and other obstetrical services were received outside of the study, pregnancy outcomes and dates were self-reported. Interviewers were trained to assess pregnancy and pregnancy outcome information from women by asking at every visit: “since your last study visit, how many times have you been pregnant?” and, for those responding with a non-zero number, “what was the outcome of the pregnancy?” Pregnancy outcomes were explained to help reduce misclassification error. Miscarriage was defined as spontaneous loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation. Other pregnancy outcomes included stillbirth, defined as a child born dead after 20 weeks of gestation, live birth, defined as a child born alive, ectopic pregnancy, defined as any pregnancy outside the uterus, and abortion, defined as any pregnancy terminated through an elective procedure.

In total, 755 women reported 1487 pregnancies with known outcomes. We excluded pregnancies that ended in stillbirths (n=11, 0.7% of total pregnancies ending in stillbirth; n=5 women with only stillbirths) or ectopic pregnancies (n=47, 3% of total pregnancies ending in ectopic pregnancy; n=16 women with only ectopic pregnancies). We also excluded pregnancies without information in the visit prior to an outcome (n=64, 4% of total pregnancies; n=29 women) and those pregnancies that ended in abortion (n=454, 31% of total pregnancies ending in abortion; n=121 women with only abortion outcomes). We excluded women in the 2011/12 wave (n=11) and Southern sites (n=25) due to small numbers (comprising 44 pregnancies). In primary analyses, we compared women reporting miscarriage to the referent group of women reporting live births. In sensitivity analyses, the referent group also included abortions.

Covariates of interest.

Baseline covariates of interest measured at enrollment included: race/ethnicity, income, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, WIHS site and enrollment wave, number of lifetime male sexual partners (categorized based on the distribution of the continuous variable and meaningful groupings), parity, prior miscarriage, and year of cART initiation for women with HIV. Due to the small number of self-reported prior STI events (<6 cases were recorded for each STI and none were individually associated with the outcome of interest), a composite variable for any prior STIs included gonorrhea, trichomonas, genital herpes, genital warts, syphilis, and chlamydia.

Time-varying covariates occur in the visit prior to the outcome of interest (and thus occur either during pregnancy or just prior to conception). Time-varying covariates of interest included: age group, alcoholic drinks per week (dichotomized as abstainers versus drinkers), marijuana use (dichotomized as yes/no) and frequency coded as none, less than weekly, 1-6 times a week, and at least daily), current cigarette smoking, any health related issues (including stroke, cancer, myocardial infarction, high blood pressure pulmonary embolism, diabetes), year of pregnancy, any new STI diagnosis (including gonorrhea, trichomonas, genital herpes, genital warts, syphilis, and chlamydia), yeast infection, bacterial vaginosis (BV) infection, and having a loop electrosurgical excision procedure.

Time-varying HIV-specific covariates of interest included: HIV viral load (dichotomized as ≥4 log10 copies/mL of plasma versus <4 log10 copies/mL of plasma for comparability with other WIHS analyses); CD4+ T-cell count (dichotomized as <350 cells/μL versus ≥350 cells/μL); ART regimen (categorized as (1) cART containing protease inhibitors (PI)-based regimen with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), (PI-based cART), (2) cART containing integrase inhibitors (II) and/or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI)-based regimens (non-PI cART) with NRTIs and (3) no cART including NRTI therapy alone or no ART); and ever having an AIDS defining illness.

Analysis methods.

We describe the frequencies of baseline categorical covariates using counts and percentages stratified by the primary outcome of interest (miscarriage versus live birth), with differences by miscarriage status quantified by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Frequencies for time-varying variables were calculated over all longitudinal visits. Descriptive analyses were calculated overall and stratified by HIV status.

To account for multiple pregnancy outcomes per woman, we modeled associations between covariates and miscarriage (versus live birth) for women overall and stratified by HIV status using mixed logistic regression models with a random intercept and an unstructured covariance matrix. Model-based point estimates (adjusted odds ratios, ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. Covariates significant in bivariate analyses at p<0.05 within a given strata (overall, living with or without HIV) were included in the corresponding multivariate models after assessing for multicollinearity. We decided a priori to include HIV status as a covariate in the model for women overall. Possible two-way interactions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking, marijuana use and drinking, and drinking and cigarette smoking were explored. In sensitivity analyses, models included both live births and abortion in the referent group. Analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Miscarriage outcomes.

Among the 548 women included in the primary analysis, 207 (38%) experienced a miscarriage during follow-up and 341 (68%) only experienced live birth. Among 226 women without HIV, 88 (39%) ever experienced a miscarriage and 138 (61%) only experienced live birth. Among 322 WLHIV, 119 (37%) ever experienced a miscarriage and 203 (63%) only experienced live birth. There was no significant difference in the proportion of women ever having a miscarriage between WLHIV versus women without HIV (37% versus 39%, respectively, p=0.638).

Baseline descriptive findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by HIV status and miscarriage, WIHS 1994-2017

| All women (N = 548) | Women living with HIV (N= 322) |

Women without HIV (N = 226) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mis carriage (n=207, 38%) |

Live birth (n=341, 66%) |

p- value |

Mis carriage (n=119, 37%) |

Live birth (n=203, 63%) |

p- value |

Mis carriage (n=88, 39%) |

Live birth (n=138, 61%) |

p- value |

||||||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | White/Other | 22 | 11 | 48 | 14 | 0.193 | 9 | 8 | 29 | 14 | 0.140 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 0.494 |

| African American | 130 | 63 | 188 | 55 | 79 | 66 | 117 | 58 | 51 | 58 | 71 | 51 | ||||

| Hispanic | 55 | 27 | 105 | 31 | 31 | 26 | 57 | 28 | 24 | 27 | 48 | 35 | ||||

| Income/year | ≤$12,000 | 108 | 55 | 184 | 56 | 0.951 | 62 | 54 | 109 | 56 | 0.726 | 46 | 55 | 75 | 56 | 0.539 |

| $12-24,000 | 47 | 24 | 75 | 23 | 27 | 24 | 51 | 26 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 18 | ||||

| >$24,000 | 43 | 22 | 70 | 21 | 25 | 22 | 36 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 34 | 26 | ||||

| Marital status | Legally/common-law married | 28 | 14 | 67 | 20 | 0.082 | 17 | 14 | 42 | 21 | 0.117 | 11 | 13 | 25 | 18 | 0.525 |

| Unmarried but living with partner | 36 | 17 | 70 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 47 | 23 | 15 | 17 | 23 | 17 | ||||

| Single/Widowed | 142 | 69 | 204 | 60 | 80 | 68 | 114 | 56 | 62 | 70 | 90 | 65 | ||||

| Education | Less than high school | 125 | 61 | 200 | 59 | 0.668 | 72 | 61 | 115 | 57 | 0.499 | 53 | 61 | 85 | 62 | 0.866 |

| High school or higher | 81 | 39 | 140 | 41 | 47 | 39 | 88 | 43 | 34 | 39 | 52 | 38 | ||||

| Employed | No | 147 | 71 | 237 | 70 | 0.708 | 90 | 76 | 150 | 74 | 0.730 | 57 | 65 | 87 | 63 | 0.792 |

| Yes | 60 | 29 | 104 | 30 | 29 | 24 | 53 | 26 | 31 | 35 | 51 | 37 | ||||

| Insurance | No | 48 | 23 | 108 | 32 | 0.035 | 18 | 15 | 51 | 25 | 0.041 | 30 | 34 | 57 | 42 | 0.241 |

| Yes | 157 | 77 | 231 | 68 | 99 | 85 | 152 | 75 | 58 | 66 | 79 | 58 | ||||

| Site group | New York | 105 | 51 | 130 | 38 | 0.038 | 62 | 52 | 76 | 37 | 0.071 | 43 | 49 | 54 | 39 | 0.281 |

| District of Columbia | 27 | 13 | 53 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 38 | 19 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 11 | ||||

| California | 53 | 26 | 111 | 33 | 27 | 23 | 61 | 30 | 26 | 30 | 50 | 36 | ||||

| Chicago | 22 | 11 | 47 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 28 | 14 | 7 | 8 | 19 | 14 | ||||

| WIHS enrollment wave | Original cohort (1994/95) | 106 | 51 | 149 | 44 | 0.087 | 69 | 58 | 98 | 48 | 0.701 | 37 | 42 | 51 | 37 | 0.444 |

| 2001/02 Recruitment | 101 | 49 | 192 | 56 | 50 | 42 | 105 | 52 | 51 | 58 | 87 | 63 | ||||

| Number lifetime male partners | 0-4 | 43 | 21 | 103 | 31 | 0.013 | 24 | 21 | 73 | 37 | 0.001 | 19 | 22 | 30 | 22 | 0.978 |

| 5-24 | 94 | 46 | 155 | 46 | 51 | 44 | 86 | 43 | 43 | 49 | 69 | 50 | ||||

| >=25 | 67 | 33 | 78 | 23 | 41 | 35 | 39 | 20 | 26 | 30 | 39 | 28 | ||||

| Parity | 0 | 62 | 30 | 89 | 26 | 0.313 | 27 | 23 | 48 | 24 | 0.530 | 35 | 40 | 41 | 30 | 0.268 |

| 1-2 | 84 | 41 | 161 | 47 | 51 | 43 | 97 | 48 | 33 | 38 | 64 | 46 | ||||

| >=3 | 61 | 29 | 91 | 27 | 41 | 34 | 58 | 29 | 20 | 23 | 33 | 24 | ||||

| Prior miscarriage | No | 130 | 63 | 237 | 70 | 0.106 | 71 | 60 | 149 | 73 | 0.011 | 59 | 67 | 88 | 64 | 0.614 |

| Yes | 77 | 37 | 104 | 30 | 48 | 40 | 54 | 27 | 29 | 33 | 50 | 36 | ||||

| Prior STI* | No | 82 | 40 | 137 | 40 | 0.853 | 39 | 33 | 78 | 39 | 0.279 | 43 | 49 | 59 | 43 | 0.368 |

| Yes | 125 | 60 | 202 | 60 | 80 | 67 | 123 | 61 | 45 | 51 | 79 | 57 | ||||

| Year of cART initiation | 1995-99 | 61 | 54 | 98 | 51 | 0.092 | ||||||||||

| 2000-3 | 32 | 29 | 61 | 32 | ||||||||||||

| 2004-8 | 15 | 13 | 21 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| 2009- | 4 | 4 | 11 | 6 | ||||||||||||

WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study; STI: sexually transmitted infection; cART: combination highly active antiretroviral therapy

Includes gonorrhea, trichomonas, genital herpes, genital warts, syphilis, chlamydia

p-values are two-tailed

The majority of women were African American (58%), earned <=$12,000 USD per year (55%), had less than a high school education (60%), were unemployed (70%), and had between 1-2 children (45%) upon entry into WIHS. Among all women, those experiencing a miscarriage were more likely (p<0.05) to be insured, be recruited from the New York WIHS sites, and have a higher number of lifetime male sex partners. Among WLHIV, those experiencing a miscarriage were more likely (p<0.05) to be insured, have a higher number of male sex partners, and have had a prior miscarriage. No differences were observed between baseline covariates and miscarriage in women without HIV.

Time-varying descriptive findings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Time-varying characteristics stratified by HIV status and miscarriage, WIHS 1994-2017

| All women (N = 848) | Women living with HIV (N = 468) |

Women without HIV (N = 380) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mis carriage (n=250, 29%) |

Live birth (n=598, 71%) |

p-value | Mis carriage (n=140, 30%) |

Live birth (n=328, 70%) |

p-value | Mis carriage (n=110, 29%) |

Live birth (n=270, 71%) |

p-value | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Variables (previous visit) | ||||||||||||||||

| Age group | <25 | 63 | 25 | 97 | 16 | 0.011 | 29 | 21 | 38 | 12 | 0.062 | 34 | 31 | 59 | 22 | 0.138 |

| 25-30 | 50 | 20 | 155 | 26 | 29 | 21 | 90 | 27 | 21 | 19 | 65 | 24 | ||||

| 30-35 | 65 | 26 | 189 | 32 | 41 | 29 | 105 | 32 | 24 | 22 | 84 | 31 | ||||

| >35 | 72 | 29 | 157 | 26 | 41 | 29 | 95 | 29 | 31 | 28 | 62 | 23 | ||||

| Alcohol use | Abstain | 118 | 49 | 450 | 81 | <.0001 | 76 | 56 | 263 | 84 | <.0001 | 42 | 40 | 187 | 77 | <.0001 |

| Drinkers | 123 | 51 | 108 | 19 | 60 | 44 | 51 | 16 | 63 | 60 | 57 | 23 | ||||

| Alcohol use frequency | Abstain | 118 | 49 | 450 | 81 | <.0001 | 76 | 56 | 263 | 84 | <.0001 | 42 | 40 | 187 | 77 | <.0001 |

| 0-7 | 101 | 42 | 89 | 16 | 46 | 34 | 45 | 14 | 55 | 52 | 44 | 18 | ||||

| >7 | 22 | 9 | 19 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 5 | ||||

| Marijuana use | No | 171 | 70 | 492 | 88 | <.0001 | 105 | 77 | 288 | 91 | <.0001 | 66 | 62 | 204 | 83 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 72 | 30 | 68 | 12 | 32 | 23 | 27 | 9 | 40 | 38 | 41 | 17 | ||||

| Marijuana use frequency | None | 171 | 71 | 492 | 88 | <.0001 | 105 | 77 | 288 | 91 | 0.001 | 66 | 64 | 204 | 84 | 0.001 |

| Less than weekly | 15 | 6 | 24 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 5 | ||||

| 1-6 times/week | 22 | 9 | 16 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 4 | ||||

| At least daily | 32 | 13 | 27 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 7 | ||||

| Cigarette smoking | No | 120 | 49 | 401 | 72 | <.0001 | 65 | 47 | 231 | 73 | <.0001 | 55 | 52 | 170 | 69 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 123 | 51 | 159 | 28 | 72 | 53 | 84 | 27 | 51 | 48 | 75 | 31 | ||||

| Health related* | No | 193 | 77 | 477 | 80 | 0.414 | 108 | 77 | 256 | 78 | 0.829 | 85 | 77 | 221 | 82 | 0.334 |

| Yes | 57 | 23 | 121 | 20 | 32 | 23 | 72 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 49 | 18 | ||||

| Pregnancy year | 1994-1997 | 50 | 20 | 86 | 14 | 0.066 | 36 | 26 | 49 | 15 | 0.023 | 14 | 13 | 37 | 14 | 0.655 |

| 1998-2001 | 46 | 18 | 85 | 14 | 29 | 21 | 57 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 28 | 10 | ||||

| 2002-5 | 74 | 30 | 215 | 36 | 39 | 28 | 124 | 38 | 35 | 32 | 91 | 34 | ||||

| ≥2006 | 79 | 32 | 208 | 35 | 36 | 26 | 95 | 29 | 43 | 39 | 113 | 42 | ||||

| Any STI diagnosis** | No | 211 | 86 | 493 | 88 | 0.564 | 114 | 83 | 265 | 84 | 0.688 | 97 | 92 | 228 | 93 | 0.608 |

| Yes | 33 | 14 | 67 | 12 | 24 | 17 | 50 | 16 | 9 | 8 | 17 | 7 | ||||

| Yeast infection | No | 200 | 82 | 434 | 78 | 0.120 | 111 | 81 | 237 | 75 | 0.177 | 89 | 84 | 197 | 80 | 0.509 |

| Yes | 43 | 18 | 126 | 23 | 26 | 19 | 78 | 25 | 17 | 16 | 48 | 20 | ||||

| BV infection | No | 186 | 80 | 356 | 85 | 0.134 | 97 | 73 | 192 | 81 | 0.066 | 89 | 90 | 164 | 90 | 0.873 |

| Yes | 46 | 20 | 63 | 15 | 36 | 27 | 44 | 19 | 10 | 10 | 19 | 10 | ||||

| LEEP procedure | No | 248 | 99 | 596 | 100 | 0.389 | 138 | 99 | 327 | 100 | 0.208 | 110 | 100 | 269 | 100 | n/a |

| Yes | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| HIV viral load | ≥4 log10 copies/mL | 45 | 33 | 43 | 14 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| <4 log10 copies/mL | 90 | 67 | 266 | 86 | ||||||||||||

| CD4 count <500 cells/μL | No | 57 | 43 | 127 | 41 | 0.759 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 77 | 57 | 183 | 59 | ||||||||||||

| cART regimen | II, NRTI, NNRTI | 23 | 17 | 71 | 22 | <.0001 | ||||||||||

| PI | 28 | 20 | 128 | 40 | ||||||||||||

| No cART | 87 | 63 | 121 | 38 | ||||||||||||

| AIDS defining illness | No | 98 | 70 | 247 | 75 | 0.235 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 30 | 81 | 25 | ||||||||||||

WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study; cART: combination highly active antiretroviral therapy; II: integrase inhibitor; NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI: protease inhibitor; STI: sexually transmitted infection; BV: bacterial vaginosis; LEEP: loop electrosurgical excision procedure

Includes stroke, cancer, myocardial infarction, high blood pressure pulmonary embolism, diabetes

Includes gonorrhea, trichomonas, herpes-2, genital warts, syphilis, chlamydia

‘n’ is given over all study intervals

p-values are two-tailed

In the visit prior to pregnancy outcomes of interest, the majority of women were older than 30 (57%), did not use alcohol (71%) or marijuana (83%), did not smoke (65%), and had no STI diagnosis (88%). Among all women, those experiencing a miscarriage were more likely (p<0.05) to be alcohol drinkers, marijuana users, and cigarette smokers. WLHIV experiencing a miscarriage were also more likely (p<0.05) to have experienced a pregnancy before 1998, have a higher viral load, and not be taking cART.

Adjusted model: All women (Table 3).

Table 3. Baseline and time-varying factors associated with miscarriage in all women, WIHS 1994-2017.

| Level | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV status | HIV+ (ref: HIV−) | 1.23 | 0.84 | 1.79 | 0.280 |

| Insurance (baseline) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.11 | 0.72 | 1.71 | 0.628 |

| Site group | New York (ref: California) | 1.84 | 1.18 | 2.86 | 0.007 |

| District of Columbia (ref: California) | 1.09 | 0.58 | 2.04 | 0.789 | |

| Chicago (ref: California) | 0.80 | 0.41 | 1.56 | 0.502 | |

| Number male partners | 5-24 (ref: 0-4) | 0.99 | 0.63 | 1.55 | 0.962 |

| >=25 (ref: 0-4) | 1.21 | 0.72 | 2.03 | 0.471 | |

| Age group (previous visit) | 25-30 (ref: <25) | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.82 | 0.007 |

| 30-35 (ref: <25) | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.022 | |

| >35 (ref: >25) | 0.63 | 0.38 | 1.05 | 0.078 | |

| Alcohol use (previous visit) | Drinkers (ref: abstainers) | 3.97 | 2.71 | 5.81 | <.0001 |

| Marijuana use (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.68 | 1.06 | 2.67 | 0.029 |

| Cigarette smoking (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.98 | 1.35 | 2.91 | 0.001 |

Mixed models with random intercept and unstructured covariance matrix

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; ref: reference; WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study

p-values are two-tailed

Factors associated (p<0.05) with miscarriage (versus live birth) included: being enrolled in the New York WIHS sites versus California sites, drinking alcohol, using marijuana in the previous visit, and cigarette smoking. Older age was protective for miscarriage. HIV status was not associated with miscarriage (p=0.280). None of the two-way interactions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking, marijuana use and drinking, and drinking and cigarette smoking were significant. In sensitivity analyses when elective abortions were included in the referent group, we found similar adjusted findings (data not tabled).

Adjusted model: WLHIV (Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline and time-varying factors associated with miscarriage in women living with HIV, WIHS 1994-2017

| Variable | Level | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance (baseline) | Yes (ref: No) | 2.30 | 1.12 | 4.72 | 0.024 |

| Number male partners | 5-24 (ref: 0-4) | 1.05 | 0.55 | 1.99 | 0.885 |

| >=25 (ref: 0-4) | 1.02 | 0.49 | 2.14 | 0.955 | |

| Prior miscarriage | Yes (ref: No) | 1.25 | 0.73 | 2.14 | 0.412 |

| Alcohol use (previous visit) | Drinkers (ref: abstainers) | 2.96 | 1.71 | 5.12 | <0.001 |

| Marijuana use (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.58 | 0.75 | 3.32 | 0.226 |

| Cigarette smoking (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 2.20 | 1.26 | 3.85 | 0.006 |

| Pregnancy year | 1998-2001 (ref: 1994-1997) | 1.02 | 0.45 | 2.34 | 0.961 |

| 2002-2005 (ref: 1994-1997) | 0.80 | 0.37 | 1.75 | 0.576 | |

| >=2006 (ref: 1994-1997) | 1.30 | 0.56 | 3.05 | 0.540 | |

| HIV viral load <4 log10 copies/mL (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 0.45 | 0.24 | 0.84 | 0.013 |

| ART regimen | cART containing II, NRTI, NNRTI (ref: No cART) | 0.69 | 0.34 | 1.40 | 0.302 |

| cART containing PI (ref: No cART) | 0.40 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.008 | |

Mixed models with random intercept and unstructured covariance matrix

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; ref: reference; WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study; cART: combination highly active antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI: protease inhibitor

p-values are two-tailed

Factors associated (p<0.05) with miscarriage (versus live birth) included: having insurance, drinking alcohol, and cigarette smoking. Lower log HIV viral load (<4 log10 copies/mL) and using a PI regimen (versus no cART) were protective for miscarriage. Women with HIV viral load <4 log10 copies/mL experienced similar miscarriage proportions compared to women without HIV (data not tabled). None of the two-way interactions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking, marijuana use and drinking, and drinking and cigarette smoking were significant. In sensitivity analyses when abortion was included in the referent group, we found similar adjusted findings.

Adjusted model: Women without HIV (Table 5).

Table 5.

Baseline and time-varying factors associated with miscarriage in women without HIV, WIHS 1994-2017

| Variable | Level | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use (previous visit) | Drinkers (ref: abstainers) | 4.16 | 2.38 | 7.28 | <.0001 |

| Marijuana use (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.82 | 0.97 | 3.43 | 0.062* |

| Cigarette smoking (previous visit) | Yes (ref: No) | 1.77 | 1.01 | 3.10 | 0.047 |

Mixed models with random intercept and unstructured covariance matrix

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; ref: reference; WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study

Point estimate is significant in sensitivity analyses including abortion in reference group (aOR=1.71; 95%CI: 1.02-2.86, p=0.041)

p-values are two-tailed

Factors associated (p<0.05) with miscarriage (versus live birth) included: drinking alcohol and cigarette smoking. None of the two-way interactions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking, marijuana use and drinking, and drinking and cigarette smoking were significant. In sensitivity analyses when abortion was included in the referent group, we found similar adjusted findings although marijuana use became statistically significant (aOR=1.71; 95%CI: 1.02-2.86, p=0.041).

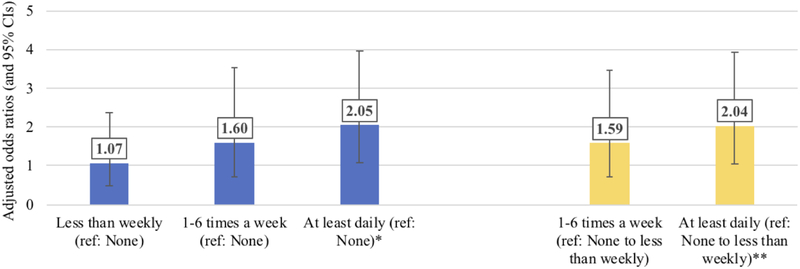

Marijuana frequencies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted association between marijuana use frequency categories and miscarriage, WIHS, 1994-2017

Odds ratios adjusted for same covariates as primary analyses

WIHS: Women's Interagency HIV Study; CI: confidence interval

*p=0.0320 comparing 'At least daily' versus 'None'

**p=0.0324 comparting 'At least daily' versus 'None to less than weekly'

In addition to dichotomized marijuana use (yes/no), frequency of marijuana use was also significant in bivariate analyses. Among all women, only the highest category of marijuana use (at least daily) reached statistical significance (p=0.032) compared to either no marijuana use or none/less than weekly marijuana use. Similar findings were observed for women living with and without HIV, though the adjusted point estimates for frequency of marijuana use did not reach statistical significance after stratifying by HIV status.

STRUCTURED DISCUSSION/COMMENT

1. Principal Findings.

In this longitudinal study, a similar proportion of women living with and without HIV reported miscarriage (37% and 39%, respectively; p=0.638). These proportions are similar to previous (1994-2002) WIHS analyses which observed 41% of women living with and 34% of women without HIV reporting miscarriage (among women reporting either a miscarriage or live birth)(5). These proportions are considerably higher than the general population in which miscarriage occurs in an estimated 10-20% of US women(4-6), which was not surprising given that women in the WIHS are on average of lower socio-economic status, report more substance use, and have more genital infections relative to the general population, all of which have been associated with miscarriage in other studies(18, 26-31).

Our study adds several years of follow-up to confirm previous WIHS findings including no association between miscarriage and HIV status(5), a positive association between miscarriage and higher HIV viral load(22), and an effect for cigarette use that is stronger among women living with versus without HIV(23). We also identified new factors associated with miscarriage: alcohol use, marijuana use frequency, and a protective effect for PI versus non-cART use. Interestingly, history of miscarriage was not associated with miscarriage.

2. Results.

Alcohol use was associated with miscarriage in this analysis. Heavy alcohol use in pregnancy has been related to negative birth outcomes, including miscarriage, and the amount and pattern of drinking likely influences these outcomes(26-28). Though we did not have sufficient sample size to evaluate moderate and heavy drinking, a systematic review reported that low to moderate drinking is not associated with negative birth outcomes including miscarriage(32). However, given that low to moderate alcohol consumption has not been shown to be definitively safe during pregnancy, US medical societies and the CDC recommend alcohol avoidance when trying to conceive or during pregnancy/breastfeeding(33).

In a previous (1994-2002) WIHS analysis by Massad et al, marijuana use in two visits prior to pregnancy in women with HIV was associated with miscarriage (aOR=6.6 compared to women with no or inconsistent use), but findings for women without HIV were not explored, nor was the effect of frequency of marijuana use for women living with and without HIV(5). In the present analysis, we found that any marijuana use was associated with miscarriage overall with a trend for increasing marijuana use. Though publications have demonstrated a potential biological mechanism for the effect of marijuana on miscarriage (primarily related to the harmful effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive in marijuana which crosses the placental barrier)(34-36), several studies failed to show an association between marijuana use and miscarriage. Earlier (1987-2002) longitudinal studies of prenatal marijuana exposure in women without HIV found no association between marijuana use during pregnancy and miscarriage(7, 37-40). However, contemporary marijuana products have higher levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol than in the 1980-90s(41). As access to marijuana increases through legalization and stigmatization diminishes, women may be more likely to accurately disclose their marijuana use and thus future studies may be more accurate. Given conflicting literature on marijuana use and adverse birth outcomes including miscarriage, low birth weight, preterm birth, and neonatal morbidity(6-12, 18, 37-40, 42), professional societies recommend women discontinue marijuana during pregnancy, while breastfeeding, or when attempting to conceive(43).

In a previous WIHS analysis, ART at the visit prior to pregnancy appeared protective against miscarriage (aOR=0.37)(5). Here, we explored specific cART regimens and found that PI-containing regimens versus no cART were significantly protective for miscarriage, while other cART regimens may also be protective (though their association did not reach statistical significance). While data are conflicting, some studies show cART to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm delivery and low birth weight(13-15). A review of studies published between 1980-2017 compared women receiving tenofovir versus non-tenofovir cART regimens during pregnancy and found no increased miscarriage risk(44), and a study of zidovudine versus non-zidovudine cART regimens found a protective effect for miscarriage(45). Meanwhile, PIs may lower progesterone levels(46) possibly leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes including miscarriage(47), preterm birth(16), and lower birth weight(17).

History of miscarriage was not associated with miscarriage in our adjusted models. This finding contradicts Massad et al in which miscarriage was significantly associated with prior miscarriage in women with HIV (aOR=1.94)(5). This difference may be related to our inclusion of an additional 15 years of study data and control for influential covariates such as alcohol and cART. Importantly, we are not differentiating between 1-2 versus recurrent prior miscarriage (3 or more), the latter being much less common and likely reflective of underlying factors that may increase miscarriage risk.

3. Research Implications.

The protective association with PIs persists when controlling for viral load, indicating that possible mechanism of protection is not conferred by viral suppression. This mechanism warrants further exploration.

4. Clinical Implications.

Alcohol consumption and marijuana use are potentially modifiable behaviors that providers can counsel on to impact miscarriage risk. The finding that PIs appeared significantly protective for miscarriage importantly adds to PI safety data.

5. Strengths and Limitations.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, miscarriage in the WIHS is self-reported. The risk of miscarriage is highest in the first several weeks of pregnancy(48) when women and their providers may not diagnose early pregnancy(49, 50). This could contribute to ascertainment bias. Additionally, use of marijuana, alcohol, tobacco use, and STI could be differentially reported by the outcome of interest, with women experiencing miscarriage perhaps less likely to report exposure. However, self-reported data in other WIHS studies has been strongly correlated with clinical outcomes. We did not have sufficient numbers to explore the role of individual STIs or levels of drinking. We also did not have measures of time-varying intimate partner violence, which may be associated with miscarriage. Future analyses could consider the role of various measures of smoking frequency and different time-varying combinations of ART regimens. Though rare, it is possible that a proportion of miscarriages could include early ectopic pregnancies. Though we excluded the 2011/2012 wave and southern due to small numbers, when combined with the analysis cohort, findings did not meaningfully change. As the southern cohort accrues more women, future analyses will be able to draw conclusions from this group. Finally, our results are most generalizable to US urban women living with and without HIV who are primarily older and African American.

6. Conclusions.

The WIHS is one of the largest and longest running cohorts of women living with and without HIV in the world and is well-validated with standardized data collection procedures and highly trained staff. Our study adds several years of analytic follow-up to confirm previous findings and identify new findings related to alcohol use, marijuana use frequency, and the protective effect of PIs. These findings highlight additional potentially modifiable behaviors addressable via interventions which could reduce miscarriage risk.

CONDENSATION:

Poorly controlled HIV-infection and tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use were associated with increased miscarriage risk while protease inhibitors were protective compared to non-combination antiretroviral treatment.

AJOG AT A GLANCE:

A. To provide a more comprehensive and contemporary evaluation of miscarriage, we assessed the frequency and factors associated with miscarriage in both women living with and without HIV enrolled in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS).

B. HIV status was not associated with miscarriage risk. Poorly controlled HIV-infection and tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use were associated with increased miscarriage risk while protease inhibitors were protective compared to non-combination antiretroviral treatment.

C. Our study adds several years of analytic follow-up to previous analyses, confirms previous findings related to HIV status and miscarriage, and identified new findings related to alcohol use, marijuana use frequency, and the protective effect of protease inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi, Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Bradley Aouizerat and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), and P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR). Dr. Dionne-Odom’s effort is supported by the NICHD (1K23HD090993). Dr. Haddad’s effort is supported by the NICHD (1K23HD078153-01A1). Dr. Wall’s effort is supported by the NIMH (K01MH107320).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Kristin M. WALL, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Heath, Department of Epidemiology, Atlanta, GA..

Dr. Lisa B. HADDAD, Emory University, School of Medicine, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Atlanta, GA..

Dr. C. Christina MEHTA, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Heath, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Atlanta, GA..

Dr. Elizabeth T. GOLUB, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Heath, Department of Epidemiology, Baltimore, MD..

Dr. Lisa RAHANGDALE, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chapel Hill, NC..

Dr. Jodie DIONNE-ODOM, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of Infectious Diseases, Birmingham, AL..

Dr. Roksana KARIM, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine, Department of Preventative Medicine, Los Angeles, CA..

Dr. Rodney L. WRIGHT, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bronx, NY..

Dr. Howard MINKOFF, Maimonides Medical Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brooklyn, NY..

Dr. Mardge COHEN, Departments of Medicine, John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County and Rush University, Chicago, IL..

Dr. Seble G. KASSAYE, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Travel Medicine, Washington DC..

Dr. Deborah COHAN, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, San Francisco, CA..

Dr. Igho OFOTOKUN, Emory University, School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases Atlanta, GA and Grady Healthcare System, Atlanta, GA..

Dr. Susan E. COHN, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Chicago, IL..

REFERENCES

- 1.Haddad LB, Wall KM, Mehta CC, Golub ET, Rahangdale L, Kempf MC, et al. Trends of and factors associated with live-birth and abortion rates among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;216(1):71.e1-.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz SR, Rees H, Mehta S, Venter WDF, Taha TE, Black V. High Incidence of Unplanned Pregnancy after Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation: Findings from a Prospective Cohort Study in South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(4):e36039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S, Parekh N, Ogwu A, Lockman S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;206(11):1695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezechi OC, Gab-Okafor CV, Oladele DA, Kalejaiye OO, Oke BO, Ohwodo HO, et al. Pregnancy, obstetric and neonatal outcomes in HIV positive Nigerian women. African journal of reproductive health. 2013;17(3):160–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massad LS, Springer G, Jacobson L, Watts H, Anastos K, Korn A, et al. Pregnancy rates and predictors of conception, miscarriage and abortion in US women with HIV. AIDS (London, England). 2004;18(2):281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Gelder MM, Reefhuis J, Caton AR, Werler MM, Druschel CM, Roeleveld N. Characteristics of pregnant illicit drug users and associations between cannabis use and perinatal outcome in a population-based study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010;109(1-3):243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Northstone K. Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2002;109(1):21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C-S, Jew CP, Lu H-C. Lasting impacts of prenatal cannabis exposure and the role of endogenous cannabinoids in the developing brain. Future neurology. 2011;6(4):459–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metz TD, Allshouse AA, Hogue CJ, Goldenberg RL, Dudley DJ, Varner MW, et al. Maternal marijuana use, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and neonatal morbidity. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;217(4):478.e1-.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center KE, Nunez A, Gibson SJ, Christ C, et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2016;6(4):e009986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, Kingsbury AM, Hurrion E, Mamun AA, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatric Research. 2011;71:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conner SN, Bedell V, Lipsey K, Macones GA, Cahill AG, Tuuli MG. Maternal Marijuana Use and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(4):713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado ES, Hofer CB, Costa TT, Nogueira SA, Oliveira RH, Abreu TF, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women infected with HIV-1 receiving combination antiretroviral therapy before versus after conception. Sexually transmitted infections. 2009;85(2):82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, Tookey PA. Antiretroviral therapy and premature delivery in diagnosed HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom and Ireland. AIDS (London, England). 2007;21(8):1019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powis KM, Kitch D, Ogwu A, Hughes MD, Lockman S, Leidner J, et al. Increased risk of preterm delivery among HIV-infected women randomized to protease versus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HAART during pregnancy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;204(4):506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bt Polgár, Nagy E Mikó Ev, Pt Varga, Jl Szekeres-Barthó. Urinary Progesterone-Induced Blocking Factor Concentration Is Related to Pregnancy Outcome1. Biology of Reproduction. 2004;71(5):1699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salas SP, Marshall G, Gutierrez BL, Rosso P. Time course of maternal plasma volume and hormonal changes in women with preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2006;47(2):203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman-Cowger VH, Oga EA, Peters EN, Mark K. Prevalence and associated birth outcomes of co-use of Cannabis and tobacco cigarettes during pregnancy. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2018;68:84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, Kahr M, Suter MA, Mastrobattista JM, et al. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016;215(4):506.e1-.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HY, Kasonde P, Mwiya M, Thea DM, Kankasa C, Sinkala M, et al. Pregnancy loss and role of infant HIV status on perinatal mortality among HIV-infected women. BMC pediatrics. 2012;12:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner AN, Tabbah S, Mwapasa V, Rogerson SJ, Meshnick SR, Ackerman WEt, et al. Severity of maternal HIV-1 disease is associated with adverse birth outcomes in Malawian women: a cohort study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2013;64(4):392–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cates JE, Westreich D, Edmonds A, Wright RL, Minkoff H, Colie C, et al. The Effects of Viral Load Burden on Pregnancy Loss among HIV-Infected Women in the United States. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;2015:362357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westreich D, Cates J, Cohen M, Weber KM, Seidman D, Cropsey K, et al. Smoking, HIV, and risk of pregnancy loss. AIDS (London, England). 2017;31(4):553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2005;12(9):1013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong BG, McDonald AD, Sloan M. Cigarette, alcohol, and coffee consumption and spontaneous abortion. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(1):85–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiodo LM, Bailey BA, Sokol RJ, Janisse J, Delaney-Black V, Hannigan JH. Recognized spontaneous abortion in mid-pregnancy and patterns of pregnancy alcohol use. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY). 2012;46(3):261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cigarette Rasch V., alcohol, and caffeine consumption: risk factors for spontaneous abortion. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2003;82(2):182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baud D, Goy G, Jaton K, Osterheld M-C, Blumer S, Borel N, et al. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis in Miscarriage. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(9):1630–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oakeshott P, Hay P, Hay S, Steinke F, Rink E, Kerry S. Association between bacterial vaginosis or chlamydial infection and miscarriage before 16 weeks' gestation: prospective community based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;325(7376):1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giakoumelou S, Wheelhouse N, Cuschieri K, Entrican G, Howie SEM, Horne AW. The role of infection in miscarriage. Human Reproduction Update. 2016;22(1): 116–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson J, Gray R, Brocklehurst P. Systematic review of effects of low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure on pregnancy outcome. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2007;114(3):243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prevention CfDCa. Alcohol and Pregnancy Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/fasd/index.html.

- 34.Huizink A Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2014;52:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trabucco E, Acone G, Marenna A, Pierantoni R, Cacciola G, Chioccarelli T, et al. Endocannabinoid system in first trimester placenta: low FAAH and high CB1 expression characterize spontaneous miscarriage. Placenta. 2009;30(6):516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedrich J, Khatib D, Parsa K, Santopietro A, Gallicano GI. The grass isn’t always greener: The effects of cannabis on embryological development. BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2016;17:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fried PA, Makin JE. Neonatal behavioural correlates of prenatal exposure to marihuana, cigarettes and alcohol in a low risk population. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1987;9(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson GA, Ryan C, Willford J, Day NL, Goldschmidt L. Prenatal alcohol and marijuana exposure: Effects on neuropsychological outcomes at 10 years. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2002;24(3):309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kline J, Hutzler M, Levin B, Stein Z, Susser M, Warburton D. Marijuana and spontaneous abortion of known karyotype. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1991;5(3):320–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Risk factors for early pregnancy loss. Epidemiology. 1990;1(5):382–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;213(6):761–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansson LM, Jordan CJ, Velez ML. Perinatal marijuana use and the developing child. JAMA. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;130(4):e205–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Mofenson LM, Anderson JR, Kanters S, Renaud F, et al. Safety of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate-Based Antiretroviral Therapy Regimens in Pregnancy for HIV-Infected Women and Their Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2017;76(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vannappagari V, Koram N, Albano J, Tilson H, Gee C. Association between in utero zidovudine exposure and nondefect adverse birth outcomes: analysis of prospectively collected data from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2016;123(6):910–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papp E, Mohammadi H, Loutfy MR, Yudin MH, Murphy KE, Walmsley SL, et al. HIV Protease Inhibitor Use During Pregnancy Is Associated With Decreased Progesterone Levels, Suggesting a Potential Mechanism Contributing to Fetal Growth Restriction. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2015;211(1):10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghupathy R, Al-Mutawa E, Al-Azemi M, Makhseed M, Azizieh F, Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) modulates cytokine production by lymphocytes from women with recurrent miscarriage or preterm delivery. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2009;80(1):91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340(23):1796–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandya PP, Snijders RJ, Psara N, Hilbert L, Nicolaides KH. The prevalence of non-viable pregnancy at 10-13 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;7(3):170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox AJ, Horney LF. Accuracy of spontaneous abortion recall. American journal of epidemiology. 1984;120(5):727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]