Abstract

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has a high burden of morbidity and mortality from premature (≤55 years in men; ≤65 years in women) myocardial infarction (MI) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Despite this, the prevalence of risk factors in patients presenting with premature MI or ACS is incompletely described. We compared lifestyle, clinical risk factors, and biomarkers associated with premature MI/ACS in the MENA region with selected non-MENA high-income countries. We identified English-language, peer-reviewed publications through PubMed (up to March 2018). We used the World Bank classification system to categorize countries. Patients with premature MI/ACS in the MENA region had a higher prevalence of smoking than older MI/ACS patients but a lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia. Men with premature MI/ACS had a higher prevalence of smoking than women, but a lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. The MENA region had sparse data on lifestyle, diet, psychological stress and physical activity. To address these knowledge gaps, we initiated the ongoing Gulf Population Risks and Epidemiology of Vascular Events and Treatment (Gulf PREVENT) case-control study to improve primary and secondary prevention of premature MI in the United Arab Emirates, a high-income country in the MENA region.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, premature myocardial infarction, risk factors, biomarkers, MENA, United Arab Emirates

Introduction

In 2015, cardiovascular disease (CVD) claimed 17.9 million lives, representing a 42% increase from 12.6 million in 1990.1 Most CVD deaths result from ischemic heart disease (IHD). While there is variation in global distribution of CVD and IHD, one region with a consistently high burden, particularly of premature CVD, is the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).2,3

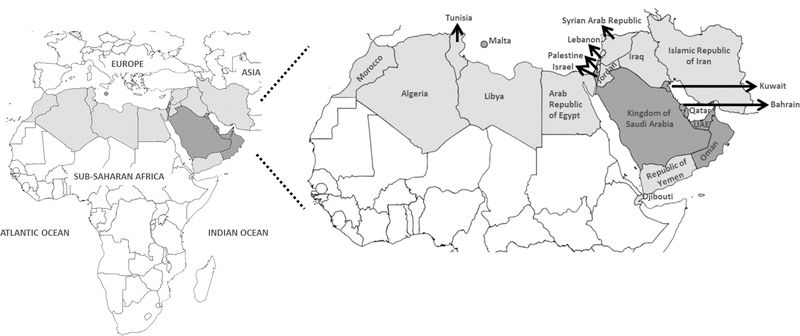

Based on the World Bank classification, MENA comprises 21 countries (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1).4 MENA has one of the highest years of life lost and disability associated with CVD and IHD (Supplemental Figures 1A-D).1 Several MENA countries have shown improvement in age-adjusted CVD death rates although the total number of CVD deaths from 1990 to 2015 increased from 29% (Somalia) to 422% (United Arab Emirates), attributed to population growth and aging (Supplemental Figure 2).5

Figure 1:

Middle East and North Africa region with middle- (light grey) and high-income (dark grey) countries.

Premature myocardial infarction (MI) generally refers to MI in men ≤55 years or women ≤65 years old.6,7 INTERHEART8 reported that the Middle East had the youngest median age of first MI (51 years), approximately a decade younger than North America (59 years) and Western Europe (63 years). MENA countries had the highest proportion (11%) of individuals ≤40 years with MI (vs 4% in North America and 3% in Western Europe).8 These findings are alarming for MENA countries, as premature MI has significant consequences for families and society, including loss of productivity, long-term health costs and high caregiver burden. Given the findings from INTERHEART8 and the paucity of reports summarizing risk factors in the MENA region, we sought to compare risk factors associated with premature MI in MENA and selected non-MENA high-income countries in North America and Europe.

We review prevalence of risk factors as well as knowledge gaps that guided development of the Gulf Population Risks and Epidemiology of Vascular Events and Treatment (Gulf PREVENT), a recently initiated and ongoing study of premature MI in the United Arab Emirates.

Methods

In this narrative review, we identified original articles through PubMed from inception to March 28, 2018 using terms: cardiovascular disease; premature myocardial infarction; individual MENA country names; biomarkers; lipids; lipoproteins; diabetes; obesity; and sex differences. We screened titles and/or abstracts of approximately 14,000 articles and included studies that described risk factors and premature MI/ACS. Countries were categorized by World Bank income group. We describe type of cardiac event: first or recurrent MI or acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We summarize risk factors in MENA and for comparison, selected non-MENA high-income countries in North America and Europe, and where available, draw comparisons by age and sex.

Figure 1 was designed with online software (mapchart.net).

Results

Description of Major Studies

We identified major studies based in several world regions (INTERHEART8 and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]9; n=51,263 individuals), studies exclusively from MENA (n=14,704 individuals from 3 studies) and from non-MENA high-income regions (n=30,299 individuals from 8 studies) (Table 1). All were cohort studies except for INTERHEART (case-control).8 Participants were recruited from hospitals with capability for fibrinolysis and/or percutaneous coronary intervention. Very few studies reported hospital characteristics and precluded us from summarizing the level (i.e. secondary, tertiary, or quaternary) of participating hospitals. Further, most studies were conducted in ≥2 countries, included men and women, and had large sample sizes (n ≥3,500) recruited from several hospitals.8–14 Studies conducted in ≤1 country also had large sample sizes (n ≥2250) recruited from several hospitals.15–17 These factors strengthen their validity of being representative of the average MI/ACS in their country or region. The regional studies included fewer hospitals but were based on contemporary cohorts, thereby improving their validity related to contemporary cardiovascular risk factors.18–20 INTERHEART8 reported age-stratified association of 9 factors with acute MI, and GRACE enrolled individuals with ACS.9 The INTERHEART Middle East substudy reported non-age stratified trends from MENA.21 Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events (Gulf RACE) enrolled individuals with ACS from 6 MENA countries.10 Gulf RACE-2 was a follow up registry of ACS.11 In few MENA countries (Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia) there were sparse reports on stable or angiographic IHD, non-age-stratified analyses and cardiovascular risk factors.7–16 For example, the Saudi Project for Assessment of Coronary Events reported non-age stratified prevalence of risk factors among individuals in Saudi Arabia with ACS31; the Jordan Hyperlipidemia And Related Targets Study (JoHARTS) reported the prevalence of risk factors among individuals in Jordan with stable IHD or ACS23; the Tehran Heart Center’s Premature Coronary Atherosclerosis Cohort Study enrolled individuals in Iran with angiographic IHD;30 and, a study in Egypt enrolled individuals with stable IHD or MI29. Given the paucity of data on premature MI/ACS in the MENA region, where relevant, we have included findings on stable or angiographic IHD and non-age-stratified analyses.

Table 1:

Summary of major studies on risk factors and premature ACS or MI

| Study/Author; year | Reference | Countries | Population | Event Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Several world regions | ||||

| INTERHEART; 2004 | 8 | 8 MENA countries: Bahrain; Arab Republic of Egypt; Islamic Republic of Iran; Israel; Kuwait; Qatar; Oman; UAE 44 other countries/regions: Western Europe; Central Europe; North America; South America; Australia and New Zealand; Africa; South Asia; China and Hong Kong; other Asia |

cases; n=12,461 controls; n=14,637 |

first MI |

| GRACE; 2005 | 9 | 14 countries/regions (none from MENA): North America; South America; Europe; Australia and New Zealand | <65y; n=11,194 ≥65y; n=12,971 |

STEMI; n=8,204 NSTE-ACS; n=15,961 |

| MENA countries | ||||

| Gulf RACE; 2011 | 10 | High-income: Bahrain; Kuwait; Oman; Qatar; UAE Middle-income: Yemen |

<40y; n=627 40–59y; n=3,437 >60y; n=2,633 |

STEMI; n=2,619 NSTE-ACS; n=4,085 |

| Gulf RACE-2; 2013 | 11 | High-income: Bahrain; Oman; Qatar; UAE; Saudi Arabia Middle-income: Yemen |

≤50y; n= 2,755 51–70y; n=4,110 >70y; n=1,065 |

STEMI; n=3,613 NSTE-ACS; n=4,317 |

| Callachan; 2017 | 19 | UAE | <40y; n=77 | MI |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | ||||

| Framingham; 1996 | 17 | US | total; n=2191 men <55y; n=79 men |

first MI |

| GISSI-2; 1997 | 15 | Italy | <50y; n=1,972 50–70y; n=6,921 >70y; n=2,590 |

MI |

| PRIAMHO II; 2007 | 16 | Spain | <45y; n=438 ≥45y; n=5,772 |

MI |

| GENESIS-PRAXY; 2014 | 14 | Canada; Switzerland; US | 18–55y; n=362 women 18–55y; n=761 men |

STEMI; n=652 NSTE-ACS; n=446 |

| VIRGO; 2016 | 12 | Spain; US | 18–55y; n=2,349 women 18–55y; n=1,152 men |

MI |

| VIRGO; 2017 | 13 | Spain; US | 18–55y; n=1,494 women 18–55y; n=725 men |

MI |

| Young-MI; 2017 | 20 | US | ≤ 50y; n=1,475 | first MI |

| Young-MI; 2018 | 18 | US | ≤ 50y; n=2,097 | first MI |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; GENESIS-PRAXY: GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: from bench to beyond–PRemature Acute Coronary Syndrome; GISSI: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; Gulf RACE: Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST segment elevation ACS; PRIAMHO: Proyecto de Registro de Infarto Agudo de Miocardio Hospitalario; RACE-2: Second Registry of Acute Coronary Events; STEMI: ST-segment elevation MI; UAE: United Arab Emirates; US: United States; VIRGO: Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute MI Patients; y: years. VIRGO and Young-MI are presented twice as data for variables were obtained from different articles.

Outside of MENA, major studies in high-income countries in North America and Europe include Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute MI Patients (VIRGO), Young-MI, GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: from bench to beyond–PRemature Acute Coronary Syndrome (GENESIS-PRAXY), Proyecto de Registro de Infarto Agudo de Miocardio Hospitalario (PRIAMHO II), and Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI-2) (Table 1).12–16

Risk Factors and Premature MI or ACS

Data are summarized in Tables 2–4.

Table 2:

Prevalence and association of lifestyle factors with premature ACS or MI.

| Study/Author (ref) | Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | younger | older | |

| Smoking | |||

| Several world regions | |||

| GRACE9 | M,F | 79% (<45y) | 29% (≥85y) |

| MENA countries | |||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

67% (<40y) 10% (<40y) |

30% (>60y) 5% (>60y) |

| Gulf RACE-211 | M,F | 67% (≤50y) | 34% (>70y) |

| Callachan19 | M,F | 61% | |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| GISSI-215 | M,F | 78% (<50y) | 21% (>70y) |

| PRIAMHO II16 | M,F | 84% (<45y) | 41% (≥45y) |

| VIRGO12 | M F |

54% 56% |

|

| GENESIS-PRAXY14 | M F |

39% 43% |

|

| Young-MI20 | M F |

51% 57% |

|

| Alcohol | |||

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| Sex | |||

| VIRGO12 | M F |

11% 5% |

|

| Physical activity | |||

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| VIRGO12 | M F |

42% 33% |

|

| Recreational drugs | |||

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| Young-MI18 | M,F | 5% (cocaine) | |

| 6% (cannabis) | |||

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; M, F: male, female; MI: myocardial infarction; GENESIS-PRAXY: GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: from bench to beyond–PRemature Acute Coronary Syndrome; GISSI: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; Gulf RACE: Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; MI: myocardial infarction; PRIAMHO: Proyecto de Registro de Infarto Agudo de Miocardio Hospitalario; VIRGO: Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute MI Patients; y: years.

Table 4:

Prevalence and association of biomarkers with premature ACS or MI.

| Study/Author (ref) |

Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | younger | older | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| Several world regions | ||||

| GRACE9 | M,F | 40% (<45y) | 23% (≥85y) | Presence of ≥1: total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL; LDL-cholesterol ≥100 mg/dL; triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL; previous/current use of lipid-lowering drugs |

| MENA countries | ||||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

14% (<40y) 21% (<40y) |

36% (>60y) 47% (>60y) |

Based on diagnosis prior to index admission |

| Gulf RACE-211 | M,F | 30% (≤50y) | 43% (>70y) | Presence of ≥1: total cholesterol >200 mg/dL; LDL-cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL; HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | ||||

| Study/Author (ref) | Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

Definition | ||

| Sex | younger | older | ||

| GISSI-215 | M,F | 47% (<50y) | 53% (>70y) | hypercholesterolemia |

| PRIAMHO II16 | M,F | 46% (<45y) | 40% (≥45y) | total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dl |

| VIRGO12 | M F |

92% 83% |

Based on patient report, chart-documentation, or lipid-lowering agent on admission | |

| Young-MI20 | M,F | 56% | Presence of ≥1: total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dl; triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL; HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL (men); HDL-cholesterol <50 mg/dL (women); diagnosis/treatment of dyslipidemia |

|

| Cholesterol | ||||

| MENA countries | ||||

| Callachan19 | M,F | 20% 30% 70% |

total cholesterol >193 mg/dL LDL-cholesterol >116 mg/dL HDL-cholesterol <39 mg/dL |

|

| Non-MENA high-income countries | ||||

| Study/Author (ref) | Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

Definition | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Young-MI20 |

M F M F M F |

mean, mg/dL (±SD) | ||

| 193±57 184±51 |

total cholesterol | |||

| 120±46 113±46 |

LDL-cholesterol | |||

| 36±10 41±14 |

HDL-cholesterol | |||

| VIRGO13 | median, mg/dL (IQR) | |||

| M F |

180 (154–212) 182 (154–213) |

total cholesterol | ||

| M F |

111 (85–142) 107 (85–134) |

calculated LDL-cholesterol | ||

| Study/Author (ref) | Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

Definition | ||

| Sex | ||||

| VIRGO13 | M F |

35 (29–42) 41 (33–50) |

HDL-cholesterol | |

| Triglycerides | ||||

| MENA countries | ||||

| Callachan19 | M,F | 14% | triglycerides >150 mg/dL | |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | ||||

| Young-MI20 |

M F |

median, mg/dL (IQR) 153 (104–230) 122 (86–177) |

triglycerides | |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; IQR: inter-quartile range; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); MI: myocardial infarction; SD: standard deviation; GENESIS-PRAXY: GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: from bench to beyond–PRemature Acute Coronary Syndrome; GISSI: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; Gulf RACE: Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; PRIAMHO: Proyecto de Registro de Infarto Agudo de Miocardio Hospitalario; VIRGO: Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute MI Patients; y: years.

See Table 1 for description of studies and abbreviations. For studies with data across multiple age groups, we selected lowest and highest age groups. To convert total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol from mg/dL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglyceride from mg/dL to mmol/L multiply by 0.01129. Data from Callachan19, VIRGO12,13, Young-MI20 are based on the total cohort.

Smoking

In INTERHEART, smoking was positively associated with risk of premature MI (odds ratio [OR] [99% confidence interval (CI)]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (3.33 [2.80–3.95]) and women ≤65 years (4.49 [3.11–6.47]).8 GRACE showed higher prevalence of smoking among younger vs older individuals with ACS.9

In Gulf RACE and Gulf RACE-2, smoking was more prevalent in younger vs older individuals with ACS,10,11 and in men vs women in Gulf RACE10. Similar results were observed in JoHARTS and in studies from Egypt, Iran and Tunisia.23,25,29,30 A study in Saudi Arabia reported 32% prevalence of smoking among individuals with ACS.31 In Gulf RACE-2, users of khat (a stimulant predominantly used in East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula) vs non-users had higher risk of recurrent MI and death.32

In non-MENA countries, smoking was more prevalent in younger vs older individuals in Italy and Spain.15,16 GISSI-2 reported higher risk of MI (OR [95% CI]; (2.87 [2.59–3.17]) in younger (<50 years) vs older (50–70 years) smokers.15 GENESIS-PRAXY and VIRGO showed no differences between men and women.12,14 Smoking is more prevalent in younger individuals with MI/ACS in non-MENA vs MENA countries. However, most studies reported presence/absence of smoking with insufficient information on duration and number of cigarettes smoked.

Other Lifestyle Factors

In INTERHEART, alcohol use was not associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (1.03 [0.87–1.23]) and women ≤65 years (0.74 [0.41–1.31]).8 None of the MENA studies reported alcohol use. In VIRGO, alcohol abuse was more prevalent in men vs women.12

In INTERHEART, regular exercise was not associated with lower risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (1.02 [0.83–1.25]) and women ≤65 years (0.74 [0.49–1.10]).8 None of the MENA studies reported physical activity or exercise. In VIRGO, physical activity was more prevalent in men vs women.12

Use of cocaine and/or cannabis in the overall cohort was reported in Young-MI and, compared to non-users, was associated with higher cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality over median follow-up time of 11.2 years.18 VIRGO reported no sex differences in cocaine use in individuals with MI.12 To our knowledge, there are no data in the MENA region.

Diabetes

In INTERHEART, diabetes was positively associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (2.66 [2.04–3.46]) and women ≤65 years (3.53 [2.49–5.01]).8 GRACE showed lower prevalence among younger vs older individuals with ACS.9

In Gulf RACE and Gulf RACE-2, younger individuals had lower prevalence of diabetes than older individuals with ACS.10,11 In JoHARTS, the prevalence of diabetes was higher in women compared with men23, and in Egypt, prevalence was higher in cases vs controls.29 In Saudi Arabia the prevalence of diabetes among individuals with ACS was 58%.31 In Iran, the prevalence was 32%, and in Tunisia, there was no difference in prevalence among individuals <65 vs ≥65 years.25,30

Similar to MENA studies, younger individuals in GISSI-2 and PRIAMHO II had lower prevalence of diabetes compared with older individuals.15,16 GISSI-2 reported lower risk of MI (0.46 [0.39–0.53]) in younger (<50 years) vs older (50–70 years) individuals with diabetes.15

Hypertension

In INTERHEART, hypertension was positively associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (1.99 [1.66–2.39]) and women ≤65 years (2.94 [2.25–3.85])8. GRACE showed lower prevalence among younger vs older individuals with ACS.9

Gulf RACE and Gulf RACE-2 showed lower prevalence of hypertension in younger vs older individuals with ACS.10,11 A study in Saudi Arabia reported 55% prevalence of hypertension among individuals with ACS.31 Results in MENA countries were generally observed in non-MENA high income countries.15,16 GISSI-2 reported lower risk of MI (0.45 [0.40–0.50]) in younger (<50 years) vs older (50–70 years) individuals with hypertension.15

Obesity

In INTERHEART, abdominal obesity (waist-to-hip ratio) was positively associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (1.83 [1.52–2.20]) and women ≤65 years (1.58 [1.14–2.20]).8 Body-mass index showed a weak positive association with MI, which became statistically non-significant when adjusted for abdominal obesity.8

In Gulf RACE, women <40 years had higher prevalence of obesity (defined by body-mass index) than men.10 Gulf RACE-2 showed higher body-mass index in individuals 51–70 years compared with other groups.11 In Egypt, prevalence of obesity was higher in cases vs controls,29 and in Iran, prevalence among premature MI was 36%.30

GENESIS-PRAXY reported no differences in prevalence between men and women, whereas VIRGO reported lower prevalence in women.12,14

Mental Health

In INTERHEART, psychosocial factors (depression, locus of control, perceived stress, and life events) were positively associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (2.62 [1.91–3.60]) and women ≤65 years (3.92 [2.26–6.79]).8

We did not find MENA studies on psychosocial factors or stress. Among non-MENA studies, VIRGO showed higher prevalence of depression in women vs men.12

Dyslipidemia

There are sparse data on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in the MENA region. INTERHEART showed that high apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio (quintiles 2–5 vs quintile 1) was positively associated with risk of premature MI (OR [99% CI]; cases vs controls) in men ≤55 years (4.16 [3.19–5.42]) and women ≤65 years (4.83 [3.19–7.32]).8 GRACE showed higher prevalence of hyperlipidemia in younger vs older individuals with ACS.9

In contrast to GRACE, Gulf RACE and Gulf RACE-2 showed lower prevalence of dyslipidemia in younger compared with older individuals.10,11 However, Gulf RACE-2 reported higher mean levels of total cholesterol and LDL-C, and lower mean levels of HDL-C, in younger vs older individuals.11 Gulf RACE-2 showed higher mean triglyceride levels in younger vs older individuals with ACS.11 In MENA studies on stable IHD, the prevalence of dyslipidemia depended on the study and type of cholesterol measured; some studies showed women with higher prevalence of dyslipidemia compared with men, and cases with higher levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C compared with controls, but lower levels of HDL-C.25,29,30

In non-MENA countries, younger vs older individuals had a higher prevalence of hypercholesterolemia16, although one study reported similar prevalence15. The trends for LDL-C and HDL-C as well as sex differences depended on the study and type of cholesterol measured (Table 4). Lipoprotein (a) was also associated with risk of premature MI in men (relative risk [95% CI]; cases vs controls 1.9 [1.1–3.3]).17

Other Biomarkers

In the MENA region, we did not find studies on inflammatory biomarkers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and premature MI. VIRGO showed higher levels of hsCRP among women vs men.33

Discussion

Our results support the following observations. First, MENA individuals with premature MI/ACS have higher prevalence of smoking compared with older individuals with MI/ACS, but lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia. Second, among individuals with premature MI/ACS, men vs women had higher prevalence of smoking, but lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Third, for several MENA countries, there are sparse data on lifestyle, diet, alcohol, psychosocial factors, obesity and physical activity. These factors may contribute to the risk of premature MI/ACS. Taken together, we observed differences in the risk factor profile of younger vs older individuals with MI/ACS and, importantly, identify knowledge gaps in the MENA region that preclude a full understanding of the factors that predispose to premature MI/ACS.

It is intriguing that younger vs older individuals with MI/ACS in MENA and non-MENA studies generally have a lower prevalence of conventional risk factors (diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia) and similar prevalence of family history of CVD. In this context, INTERHEART showed that a composite of 9 factors (lifestyle factors and apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1 ratio) account for >90% of population attributable risk of premature MI.8 However, the INTERHEART Middle East substudy did not report age-stratified analyses, and the extent to which these factors account for premature MI/ACS is unclear. Factors such as lifestyle (e.g. physical activity, psychosocial stress), access to preventive care, prior or concurrent inflammatory or infectious conditions,34 or environmental factors,35 which alter risk of MI/ACS, may contribute to premature MI/ACS, but require further investigation in MENA cohorts.

In addition, we noted differences in risk profile of men vs women. In MENA studies, men had a higher prevalence of smoking, but lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Recent studies show that sex-specific factors, in particular, obstetric history (e.g., gestational diabetes or hypertension, preeclampsia, preterm delivery) might increase risk of CVD.36 Whether or not these factors affect risk of premature MI/ACS in MENA cohorts remains to be determined.

Our study has limitations. There was variability across studies in type of event (first or recurrent ACS or MI), age cut-off for premature MI/ACS, as well as unavailable data on medication use which could affect biomarker levels. Further, several MENA studies include contemporary cohorts whereas non-MENA studies include older cohorts. This could affect the interpretation of our results.

Our study also has strengths. We examined several studies and compared risk factors in the MENA region vs selected non-MENA countries. We also examined various lifestyle, clinical risk factors, and biomarkers that could alter risk of premature MI/ACS. Importantly, we identified several knowledge gaps. INTERHEART Middle East substudy and Gulf registries did not focus on premature MI/ACS. Further, Gulf registries included MI cases without controls, and the relative contribution of socioeconomic, demographic, and psychosocial factors, as well as physical activity, to premature MI was incompletely characterized. Further, no studies have assessed barriers to adherence of secondary prevention therapies following premature MI.

Rationale for the Gulf PREVENT Study

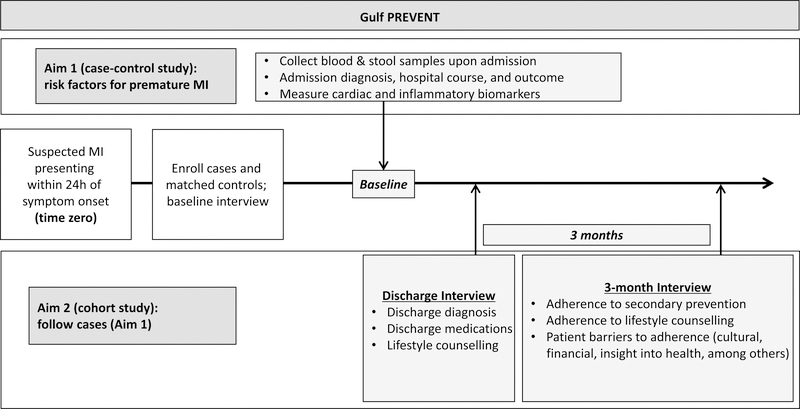

To address these gaps, we designed Gulf PREVENT, an on-going case-control study based at the largest public sector hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Figure 2). For risk factors, Gulf PREVENT will quantify the relative contribution and population attributable risk percent associated with premature MI, with emphasis on diabetes, obesity, and familial hypercholesterolemia given their growing prevalence in the Middle East.34,37 We aim to enroll 400 cases (men 18–55 years; women 18–65 years, with first MI) and a similar number of controls matched by age (±5 years), sex and nationality. MI will be determined by symptoms, cardiac biomarkers, and electrocardiographic criteria outlined by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology.38,39 Although risk factors associated with the first and recurrent cardiovascular events may be similar,40 to avoid potential bias, Gulf PREVENT will only recruit patients with first MI. Upon admission to the hospital, participants are requested to complete a baseline survey, and asked to provide blood and stool samples for banking. This will allow us to examine if novel biomarkers (e.g. novel lipids, inflammatory markers, metabolites and microbiota) can improve risk prediction of premature MI (Supplemental Table 2). Cases are interviewed at discharge and at 3 months after discharge (Figure 2). Gulf PREVENT aims to better understand premature MI across the care spectrum. These results will help to design interventions to improve primary prevention in the MENA region.

Figure 2:

Schematic of Gulf PREVENT, ongoing case-control study on premature MI in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Gulf PREVENT: Gulf Population Risks and Epidemiology of Vascular Events and Treatment; MI: myocardial infarction.

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals with premature MI/ACS in the MENA region appear to have higher prevalence of smoking than older individuals, but lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia. The sparse data on lifestyle, diet, psychological stress, and physical activity, will be addressed by the ongoing Gulf PREVENT study, which is designed to address knowledge gaps and improve cardiovascular prevention in MENA.

The goal of reducing premature cardiovascular mortality is a global priority. To achieve this, nations require a framework to improve cardiovascular outcomes, which includes high-quality clinical care and a complementary research agenda that focuses on communities and individuals. Gulf PREVENT will contribute to this framework by identifying areas to improve primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention.

Supplementary Material

Table 3:

Prevalence and association of comorbidities with premature ACS or MI.

| Study/Author (ref) | Prevalence of risk factor (age in years [y]) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | younger | older | |

| Diabetes | |||

| Several world regions | |||

| GRACE9 | M,F | 12% (<45y) | 21% (≥85y) |

| MENA countries | |||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

17% (<40y) 37% (<40y) |

42% (>60y) 56% (>60y) |

| Gulf RACE-211 | M,F | 31% (≤50y) | 46% (>70y) |

| Callachan19 | M,F | 5% | |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| GISSI-215 | M,F | 9% (<50y) | 17% (>70y) |

| PRIAMHO II16 | M,F | 9% (<45y) | 31% (≥45y) |

| GENESIS-PRAXY14 | M F |

14% 23% |

|

| VIRGO12 | M F |

20% 32% |

|

| Young-MI20 | M F |

16% 19% |

|

| Hypertension | |||

| Several world regions | |||

| Sex | younger | older | |

| GRACE9 | M,F | 34% (<45y) | 66% (≥85y) |

| MENA countries | |||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

21% (<40y) 50% (<40y) |

56% (>60y) 74% (>60y) |

| Gulf RACE-211 | M,F | 34% (≤50y) | 60% (>70y) |

| Callachan19 | M,F | 20% | |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| GISSI-215 | M,F | 14% (<50y) | 39% (>70y) |

| PRIAMHO II16 | M,F | 22% (<45y) | 48% (≥45y) |

| GENESIS-PRAXY14 | M F |

45% 55% |

|

| VIRGO12 | M F |

62% 64% |

|

| Young-MI20 | M F |

44% 45% |

|

| Obesity, body-mass index ≥ 30 kg/m210 or ≥ 25 kg/m219 | |||

| MENA countries | |||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

21% (<40y) 48% (<40y) |

22% (>60y) 37% (>60y) |

| Callachan19 | M,F | 53% | |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| Sex | younger | older | |

| VIRGO12 | M F |

26% 23% |

|

| Young-MI20 | M F |

28% 37% |

|

| GENESIS-PRAXY14 | M F |

39% 43% |

|

| Family History | |||

| MENA countries | |||

| Gulf RACE10 | M F |

11% (<40y) 19% (<40y) |

12% (>60y) 16% (>60y) |

| Gulf RACE-211 | M,F | 13% (≤50y) | 9% (>70y) |

| Non-MENA high-income countries | |||

| GISSI-215 | M,F | 38% (<50y) | 21% (>70y) |

| GENESIS-PRAXY14 | M F |

20% 28% |

|

| Young-MI20 | M F |

28% 31% |

|

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; MI: myocardial infarction; GENESIS-PRAXY: GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: from bench to beyond–PRemature Acute Coronary Syndrome; GISSI: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; Gulf RACE: Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; PRIAMHO: Proyecto de Registro de Infarto Agudo de Miocardio Hospitalario; VIRGO: Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young Acute MI Patients; y: years.

Acknowledgments

Gulf PREVENT is supported by a United Arab Emirates-Harvard Medical School Cooperative Research Award (Dubai, United Arab Emirates) to SM and AAA. SM is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA [grant numbers R01HL134811, R01 DK112940, and K24 HL136852]. ZF is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) T32 HL007575. This study was presented in part as an abstract at the National Lipid Association Meeting, April 2018, in Las Vegas, United States

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: the authors do not have any conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and Epidemiologic Drivers of Global Cardiovascular Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth GA, Nguyen G, Forouzanfar MH, Mokdad AH, Naghavi M, Murray CJL. Estimates of Global and Regional Premature Cardiovascular Mortality in 2025. Circulation. 2015;132:1270–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Bank Group. World Bank country and lending groups. https://data.worldbank.org/region/middle-east-and-north-africa?view=chart. Published 2018. Accessed April 26, 2018.

- 5.Mokdad AH, Mokdad AH. Burden of cardiovascular diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2015: findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(Suppl 1):137–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Sutter J, De Bacquer D, Kotseva K, et al. Screening of family members of patients with premature coronary heart disease; results from the EUROASPIRE II family survey. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lloyd-Jones DM, Nam B-H, D’Agostino RB, et al. Parental cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged adults: a prospective study of parents and offspring. JAMA. 2004;291:2204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Am Heart J. 2005;149:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Menyar A, Zubaid M, Shehab A, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular risk factors among patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome in the Middle East. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed E, AlHabib KF, El-Menyar A, et al. Age and clinical outcomes in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:134–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, et al. Sex differences in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: A VIRGO study analysis. Eur Hear J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;6:610–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Zhou S, Dreyer RP, et al. Sex differences in lipid profiles and treatment utilization among young adults with acute myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO Study. Am Heart J. 2017;183:74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelletier R, Humphries KH, Shimony A, et al. Sex-related differences in access to care among patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. CMAJ. 2014;186:497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moccetti T, Malacrida R, Pasotti E, et al. Epidemiologic variables and outcome of 1972 young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Data from the GISSI-2 database. Investigators of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI-2). Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:865–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morillas P, Bertomeu V, Pabón P, et al. Characteristics and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in young patients. The PRIAMHO II study. Cardiology. 2007;107:217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bostom AG, Cupples LA, Jenner JL, et al. Elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease in men aged 55 years and younger. A prospective study. JAMA. 1996;276:544–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeFilippis EM, Singh A, Divakaran S, et al. Cocaine and marijuana use among young adults presenting with myocardial infarction: The Partners YOUNG-MI registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2540–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callachan EL, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Wallis LA. Analysis of risk factors, presentation, and in-hospital events of very young patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Saudi Hear Assoc. 2017;29:270–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh A, Collins BL, Gupta A, et al. Cardiovascular risk and statin eligibility of young adults after an MI: Partners YOUNG-MI registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehani AA, Al-Hinai AT, Zubaid M, et al. Association of risk factors with acute myocardial infarction in Middle Eastern countries: the INTERHEART Middle East study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moustaghfir A, Haddak M, Mechmeche R. Management of acute coronary syndromes in Maghreb countries: The ACCESS (ACute Coronary Events – a multinational Survey of current management Strategies) registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105:566–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammoudeh AJ, Al-Tarawneh H, Elharassis A, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in Jordanians with coronary heart disease: The Jordan Hyperlipidemia and Related Targets Study (JoHARTS). Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bahri R, Esteban E, Moral P, Hassine M, Hamda K, Chaabani H. Apolipoprotein gene polymorphisms and plasma levels in healthy Tunisians and patients with coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baccouche H, Belguith AS, Boubaker H, et al. Acute coronary syndrome among patients with chest pain: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Int J Cardiol. 2016;214:531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Omar MI, Raal FJ, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor burden in Africa and the Middle East: The Africa Middle East Cardiovascular Epidemiological (ACE) Study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abduelkarem AR, El-Shareif HJ, Sharif SI . Evaluation of risk factors in acute myocardial infarction patients admitted to the coronary care unit, Tripoli Medical Centre, Libya. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:332–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdallah M, Karrowni W, Shamseddeen W, et al. Acute coronary syndromes: clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, 2002–2005. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:E6–E13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abd El-Aziz TA, Mohamed RH. LDLR, ApoB and ApoE genes polymorphisms and classical risk factors in premature coronary artery disease. Gene. 2016;590:263–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbasi SH, Kassaian SE, Sadeghian S, et al. Introducing the Tehran Heart Center’s Premature Coronary Atherosclerosis Cohort: THC-PAC Study. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2015;10:34–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alhabib KF, Hersi A, Alfaleh H, et al. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes: results of the Saudi project for assessment of coronary events (SPACE) registry. J Saudi Hear Assoc. 2011;23:233–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali WM, Al Habib KF, Al-Motarreb A, et al. Acute coronary syndrome and khat herbal amphetamine use: an observational report. Circulation. 2011;124:2681–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Zhou S, Dreyer RP, et al. Sex differences in inflammatory markers and health status among young adults with acute myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10;e003470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Libby P, Loscalzo J, Ridker PM, et al. Inflammation, Immunity, and Infection in Atherothrombosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2071–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2054–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulati M. Improving the Cardiovascular Health of Women in the Nation Moving Beyond the Bikini Boundaries PERSPECTIVE. Circulation. 2017;135:495–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Rasadi K, Al-Zakwani I, Alsheikh-Ali AA, et al. Prevalence, management, and outcomes of familial hypercholesterolemia in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the Arabian Gulf. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:685–92.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation. 2014; 130: e344–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61 485–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mora S, Wenger NK, Demicco DA, et al. Determinants of residual risk in secondary prevention patients treated with high-versus low-dose statin therapy: the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Circulation. 2012;125:1979–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.