Abstract

Background

Low health and financial literacy may be an early behavioral manifestation of cognitive impairment, dementia, and accumulating Alzheimer’s pathology. However, there are limited studies investigating the behavioral features associated with hyperphosphorylated transactive response DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43), a common age-related pathology, and even fewer studies investigating the neurobiological basis underlying low literacy in aging.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that TDP-43 pathology is associated with lower literacy.

Methods

Data came from 293 community-based older persons who were enrolled in two ongoing studies of aging. Participants completed literacy and cognitive assessments, consented to brain donation, and underwent detailed neuropathological evaluation for AD and TDP-43. Linear regression models assessed the association of TDP-43 with literacy after adjusting for demographics, and AD pathology. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons examined whether the level of literacy differed by TDP-43 stage.

Results

TDP-43 pathology was associated with lower literacy (estimate=−3.16; SE=0.86; p<0.001), above and beyond demographics and AD pathology, and this association persisted even after additionally adjusting for global cognition (estimate=−1.53; SE=0.74; p=0.038). Further, literacy was lower among persons with neocortical TDP-43 pathology compared to those without TDP-43 pathology.

Conclusion

TDP-43 pathology is associated with lower health and financial literacy in old age, above and beyond AD pathology.

Keywords: TDP-43, aging, domain-specific literacy, pathology

Introduction

Literacy is an important prerequisite for independent living and instrumental to the health and well-being of individuals, especially in older adults. The term ‘literacy’ is a multi-dimensional construct encompassing a wide range of domain-specific competencies. Older adults over the age of 65 years, the fastest growing population, have low levels in two specific domains of literacy, health and financial literacy, an important determinant for adverse health outcomes 1, 2. While there is a complex interplay between literacy and cognition, other diverse social skills and resources extending beyond cognition are important. We and others have reported health and financial literacy in older adults is associated with lower language comprehension skills (education and word knowledge), poorer decision-making 3–5, increased hospitalization, higher healthcare expenditures, and mortality 6, 7.

Emerging data suggest that higher literacy may protect against the effects of biological aging and play an important role in the maintenance of cognitive health 8, 9. Conversely, lower literacy is associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s dementia 10, 11. Clinical-pathological studies have been imperative in expanding our knowledge and providing new insights regarding relationships between age-related brain pathologies, cognitive impairment, and dementia. While studies have extensively investigated the degree to which common age-related pathologies contribute to cognition and dementia, there is limited data investigating how accumulation of neuropathologies in the aging brain relates to literacy in older adults. We previously reported that lower literacy in older persons is associated with an increased burden of AD pathology at death, independent of cognition 12, suggesting that the clinical manifestation of common age-related brain pathologies extends beyond cognitive abilities, and may affect other complex functional domains including health and financial literacy.

To our knowledge, the association of pathological burden of hyperphosphorylated transactive response DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43) with health and financial literacy has yet to be explored. We hypothesized that TDP-43 may detrimentally affect literacy in older adults for several reasons. First, TDP-43 is a common age-related neurodegenerative pathology found in over half of post-mortem brains from community-based older persons 13. Second, TDP-43 pathology has a stereotypical progression throughout the aging brain, largely affecting medial temporal brain structures 14, which may impact the integrity of white matter connections that facilitate communication between multiple cortical brain regions associated with literacy 15, 16. Third, TDP-43 pathology is associated with cognitive impairment, independent of AD pathology 17, in older persons. Lastly, in those diagnosed with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), TDP-43 pathology is associated with changes in language, decision making, and personality-traits, all of which are critical skills necessary for acquiring domain-specific knowledge and maintaining literacy function 18. Overall, there have been limited studies investigating early behavioral features linked to TDP-43 pathology in older adults and even fewer studies addressing the neurobiological basis of low literacy in old age.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that TDP-43 pathology is associated with health and financial literacy, independent of age, sex, education, and AD pathology. We collected clinical and post-mortem pathologic data from 293 older adults, above the age of 65, from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and the Religious Orders Study (ROS), two longitudinal clinical pathologic studies of aging. Additional analyses examined whether associations between TDP-43 pathology and literacy remained significant after further adjusting for cognitive function and whether literacy levels differed by pathologic staging of TDP-43.

Material and Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled in two ongoing longitudinal clinical pathologic studies of aging and dementia, Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) and the Religious Orders Study (ROS) 19. Rush MAP started in 1997 and recruits older adults from senior housing facilities and retirement communities across the Chicagoland metropolitan area. ROS started in 1994 and recruits older priests, nuns, and brothers from 45 sites across the United States. Participants in both studies enroll without known dementia, agree to undergo annual clinical evaluation and interview, including detailed neuropsychological testing, and consent to organ donation at the time of death. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Rush University Medical Center 19, 20.

At the time of the analyses, Rush MAP and ROS recruited cumulatively 3,503 older persons, of which 3,420 completed baseline cognitive assessments. Assessments of literacy were added beginning in 2010. Of 1,214 persons alive and in study since the literacy assessment began, 1,196 persons (98%) completed both cognitive and literacy assessments, and out of those 341 participants died and 307 were autopsied. We further restricted our sample to 293 (95%) participants who came to autopsy and had complete TDP-43 neuropathology data. None of these cases had a pathological diagnosis of FTLD. The mean age at death was 90.9 year (SD=6.08), mean education was 15.3 years (3.18), and 214 (73%) were female.

Literacy and Cognitive Assessment

Literacy was assessed using a battery of 32 questions. The battery of questions was designed to assess domain-specific knowledge and utilization of health and financial information and concepts relevant to older adults. The health literacy component includes 9 items that assess knowledge of Medicare, prescription instruction, leading causes of death in the older population, and understanding drug risk. The financial component of the literacy assessment includes 23 items, some adapted from the Health and Retirement Survey, and assesses knowledge of financial topics, including stocks and bonds and compound interest. Out of the 32 items, questions were true/false or multiple choice and scored as correct or incorrect. Percent correct was calculated separately for financial and health items, and a composite score for total literacy was obtained by averaging the two subscale percentages. For this study, we focused on total literacy proximate-to-death. In previous studies, total literacy had psychometric properties, and related to health outcomes 3,5,19.

A standard uniform annual cognitive assessment was administered to each participant at baseline and at each follow-up evaluation, using a battery of 19 neuropsychological tests. This assessment covers a broad range of cognitive abilities, including memory, attention, language, perception, and orientation. The Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE) and Complex Ideation Material (2 tests) were used only for clinical descriptive purposes. The remaining 17 tests were grouped to measure 5 dissociable cognitive domains: episodic memory (7 tests), semantic memory (3 tests), working memory (3 tests), perceptual speed (2 tests), and visuospatial ability (2 tests). Raw individual scores from each measure were converted to z-scores using the baseline mean and standard deviation. A composite measure of global cognition was obtained by averaging z-scores across all 17 tests, with higher scores indicating better cognitive performance, as previously described 21. In this study, we examined global cognition proximate-to-death in analyses.

Neuropathologic assessment of AD and TDP-43

The average post-mortem interval was 10.1 hours (SD=7.70), and brain autopsy follows standard procedure, as previously described 22. Following macroscopic examination of the brain, one hemisphere was fixed for at least 48–72 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer, cut into 1cm coronal slabs, and designated for diagnostic purposes.

As previously described, AD pathology was assessed from 5 brain regions: midfrontal, middle temporal, entorhinal, and parietal cortices, and hippocampus 22. Paraffin-embedded blocks were sectioned at 6μm thickness, and stained with a modified Bielschowski silver stain. Manual counts of neuritic and diffuse plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles in an area of greatest density from each region were scaled using a region-specific standard deviation, and then averaged across all 5 regions to create summary scores. A composite global AD pathology score was obtained by averaging the summary scores for each of the 3 AD pathologies, and this composite measure was used in our analyses. A pathological diagnosis of AD was determined by intermediate or high likelihood using the modified National Institute on Aging-Reagan (NIA-Reagan) criteria 23, and used for descriptive purposes.

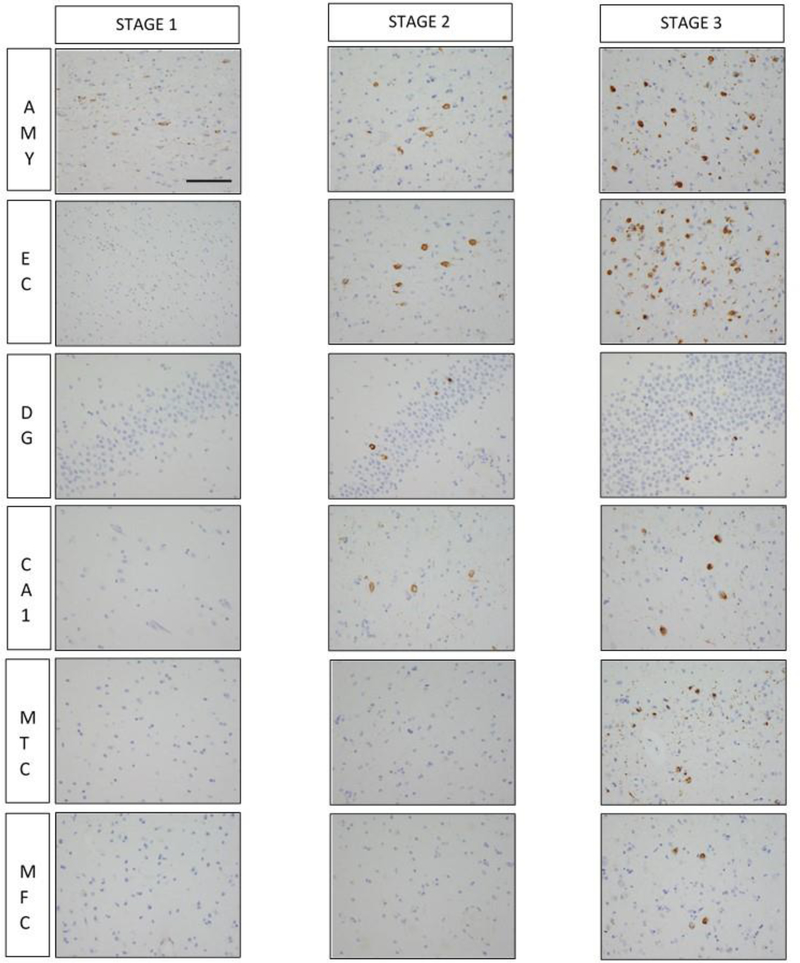

TDP-43 immunohistochemistry was performed on 6 brain regions: amygdala, hippocampus (CA1 subfield and dentate gyrus), entorhinal, midtemporal, and midfrontal cortices. This was done using a rat phosphorylated monoclonal TDP-43 antibody (Ser409/Ser410; 1:100; Ascenion, Munich, Germany). Semi-quantitative measures of pathogenic TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in each region were predetermined based on the number of inclusions in a 0.25mm2 area of greatest density using a 6-point scale, as previously descried 24. We created 3 distinct TDP-43 stages based on pathological distribution of TDP-43 in older persons: stage 1 (TDP-43 pathology localized to the amygdala), stage 2 (extending to limbic structures including hippocampus and/or entorhinal cortex), and stage 3 (extending into the neocortex) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 -. Pathological distribution of TDP-43 across each of the stages.

In stage 1, TDP-43 pathogenic inclusions are observed only in the amygdala. In stage 2, TDP-43 pathogenic inclusions extend into limbic structures including the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Lastly in stage 3, TDP-43 immunoreactivity is widespread and affects the neocortex. Abbreviations: AMY – amygdala; EC – entorhinal cortex; DG – dentate gyrus; CA1 – hippocampal CA1 subfield; MTC – middle temporal cortex; MFC – midfrontal cortex. Scale bar = 25μm. All images are same magnification.

Statistical analyses

Pearson correlation, t-test, chi-square, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests described bivariate associations between demographics, cognitive and literacy measures proximate-to-death, and neuropathology (AD and TDP-43 pathology). Linear regression models were performed to examine the independent association of TDP-43 with literacy proximate-to-death. Previous studies show a relationship between AD pathology and literacy 12; we therefore adjusted for demographics and AD pathology in initial models. Subsequent analyses further adjusted for global cognition. Because the association with literacy may not be proportional across TDP-43 staging, we also performed an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and post-hoc comparisons to examine the difference in total literacy between TDP-43 stages. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using Tukey Kramer correction. All analyses were conducted with SAS/STAT software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) using a Hewlett Packard server with a Linux operating system.

RESULTS

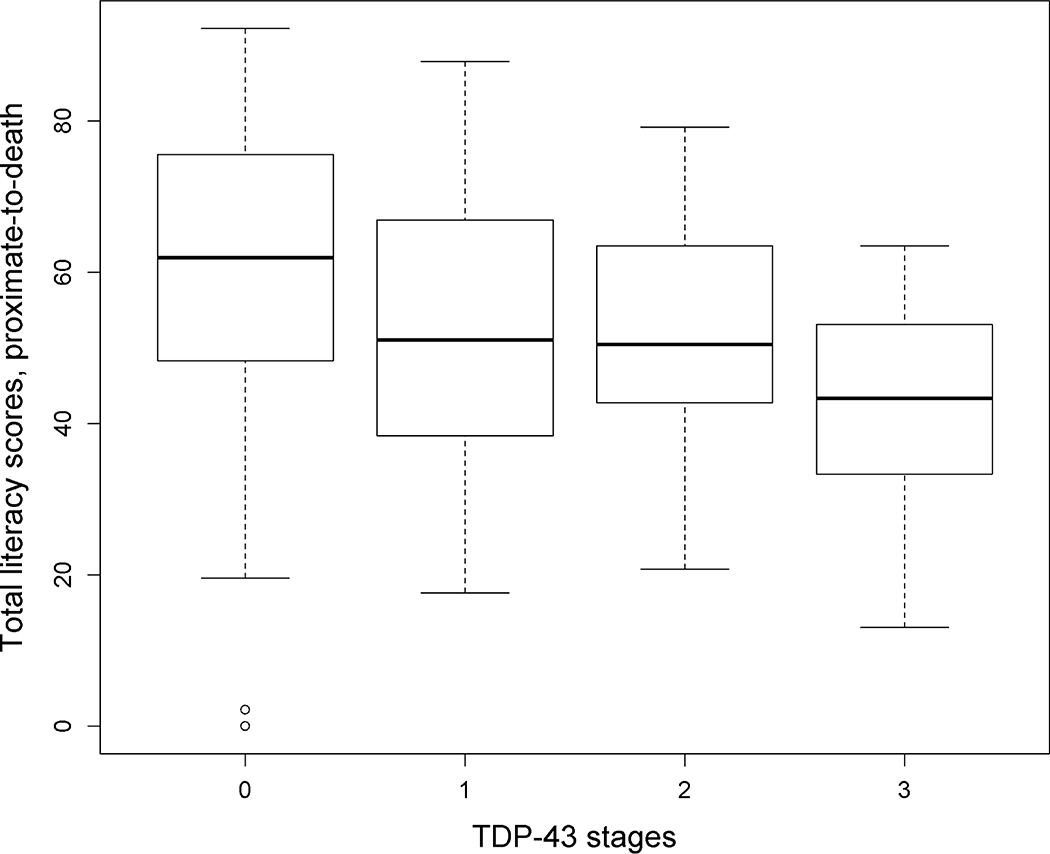

Pathogenic TDP-43 inclusions were present in 143 (48.8%) older participants, with 58 having TDP-43 pathology confined to the amygdala (stage 1), 45 with extension of TDP-43 pathology to limbic structures (hippocampus and/or the entorhinal cortex; stage 2), and 40 with TDP-43 in neocortical brain regions (stage 3). Pathologic diagnosis of AD was frequent (n=198, 67.8%), with 108 (36.9%) participants having both a pathologic diagnosis of AD and any TDP-43 pathology. Demographic, clinical, and pathologic data for participants in each of the TDP-43 stages are shown in Table 1. Similar to previous reports, older age was correlated with lower literacy (r=−0.27, p<0.001), and male participants had higher literacy score than female participants (t value =−4.77, p<0.001). Persons with higher stages of TDP-43 pathology had lower literacy (F (3, 289) =12.29, p<0.001) (Figure 2) and global cognition (F (3, 289) =10.09, p<0.001), and were more likely to have a pathologic diagnosis of AD (X2=13.4, degrees of freedom=3, p=0.004).

Table 1-.

Characteristics of participants across TDP-43 stages (n=293)

| TDP-43 Stages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0, n=150 | Stage 1, n=58 | Stage 2, n=45 | Stage 3, n=40 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age-at-death, y, mean (SD) | 89.5 (6.50) | 91.3 (6.17) | 93.0 (4.75 | 101.6 (4.11) |

| Female, n % | 103 (68.7%) | 43 (74.1%) | 31 (68.9%) | 37 (92.5%) |

| Education, y, mean (SD) | 15.4 (3.37) | 18.8 (3.14) | 14.8 (2.92) | 15.6 (2.61) |

| Clinical (proximate-to-death) | ||||

| Literacy score, mean (SD) | 60.5 (17.93) | 53.1 (17.70) | 52.36 (15.40) | 43.1 (13.35) |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 24.0 (6.96) | 22.2 (8.22) | 22.05 (6.95) | 16.6 (9.51) |

| Global cognition, mean (SD) | −0.5 (1.07) | −0.7 (1.05) | −0.9 (1.04) | −1.5 (1.01) |

| Pathologic | ||||

| AD pathology score, mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.07) | 0.8 (0.62) | 0.7 (0.49) | 1.09 (0.59) |

| NIA-Reagan, n (%) | 90 (60%) | 40 (69.0%) | 32 (71.1%) | 36 (90.0%) |

Abbreviations: y – Years; SD – Standard deviation, MMSE – Mini-Mental-State-Examination; AD – Alzheimer’s disease; TDP-43 – Transactive response DNA-Binding Protein 43

Figure 2 -.

Boxplot showing literacy scores across TDP-43 stages

We next examined the association of total literacy with TDP-43 pathology using linear regression models. First, in a model adjusted for demographics, TDP-43 pathology was associated with lower level of literacy proximate-to-death (Table 2, Model 1). Next, we added a term for global AD pathology score (Table 2, Model 2). In this model, TDP-43 pathology remained associated with lower literacy (estimate for TDP=−3.16; SE=0.86; p<0.001). AD pathology was also independently associated with lower literacy in this model (estimate=−7.76; SE=1.60; p<0.001). Because cognition and literacy are strongly associated 3, 12 and because TDP-43 pathology is an independent predictor of global cognition 17, 24, we next assessed the robustness of the association of TDP-43 with literacy global cognition as a covariate (Table 2, Model 3). In this model, the association between TDP-43 pathology and lower literacy remained significant, although the effect was attenuated (estimate=−1.53; SE=0.74; p=0.038). Interestingly, the previously observed association between AD pathology and literacy was no longer significant.

Table 2-.

Relation of TDP-43 with literacy

| Model terms | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-at-death | −0.45 (0.18, 0.013) | −0.46 (0.15, 0.003) | −0.34 (0.13, 0.008) |

| Male sex | 13.52 (2.45, <0.001) | 6.83 (2.08, 0.001) | 8.51 (1.75, <0.001) |

| Education | 1.06 (0.34, 0.002) | 0.94 (0.29, 0.001) | 0.37 (0.25, 0.13) |

| TDP-43 | −3.89 (0.88; p<0.001) | −3.16 (0.86, <0.001) | −1.53 (0.74, 0.038) |

| AD pathology | −7.76 (1.60, <0.001) | 0.05 (1.51, 0.98) | |

| Global Cognition | 9.25 (0.83, <0.001) |

Values are based on linear regression model adjusting for model terms. Cell entries are estimate (SE, p-value)

Since the association of TDP-43 stage with literacy may not be proportional, we conducted an analysis of covariance examining literacy across TDP-43 stages. Consistent with the linear regression results, we observed a strong overall association between TDP-43 pathology and lower literacy scores after for age, sex, education, and AD pathology [F (df1=7, df2=285) =16.01, p<0.001]. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons of adjusted means showed differences in literacy between persons with no TDP-43 pathology and those with neocortical TDP-43 pathology (stage 3) (p=0.005). However, persons with amygdala-only (stage 1) or limbic-type TDP-43 (stage 2) did not show significant differences compared to persons with no TDP-43 pathology (Table 3).

Table 3-.

Pairwise comparisons of adjusted means for literacy scores across TDP-43 stages

| Stage 1(Amygdala-only) | Stage 2(Limbic-type) | Stage 3(Neocortical-type) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 (No TDP-43) | p=0.15 | p=0.15 | p=0.005 |

| Stage 1 (Amygdala-only | p=0.10 | p=0.46 | |

| Stage 2 (Limbic-type) | p=0.62 |

Comparison of total literacy means across different TDP-43 stages are adjusted for age, sex, education, and AD pathology. Cell entries are p-values.

DISCUSSION

In this clinical pathologic autopsy study, we leveraged neuropathology data from nearly 300 older adults to examine the association between pathologic burden of TDP-43 pathology and literacy. We found that TDP-43 pathology is associated with lower literacy among older persons independent of AD pathology. Further, the association of TDP and literacy is not fully attributable to cognitive function, suggesting that lower literacy may be a distinct behavioral manifestation of TDP pathology in the aging brain. Furthermore, compared to persons with no TDP-43 pathology, those with neocortical TDP-43 exhibited lower literacy, suggesting that older persons with advanced TDP-43 pathology may be particularly disadvantaged when confronted by complex medical and financial matters.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to relate TDP-43 pathology with lower literacy. There are very limited data that offer insight into the neurobiological basis underlying low literacy in old age or the behavioral manifestations of TDP-43 other than cognitive impairment. Literacy assessments can be longitudinal; we have previously shown persons with lowered literacy at baseline are associated with a higher burden of AD pathology, above and beyond cognition 12. Our current study extends these findings in several ways. First, these data suggest TDP-43 pathology is associated with lower literacy independent of AD pathology. Second, TDP-43 pathology appears to be partly influencing literacy via its effect on knowledge or behavior not captured by traditional, performance-based cognitive assessments. Lastly, our findings show that cognition accounts for a greater proportion of shared variance between AD pathology and literacy compared to TDP-43 and literacy, suggesting that the effect of AD pathology with literacy works primarily through cognition, whereas TDP-43 pathology does not. Unlike our previous study 12, the association of AD pathology with lower literacy was not significant after adjusting for cognitive function in the present analyses; this might be due to the current study’s larger sample size, the use of literacy measure proximate-to-death as oppose to using literacy measures obtained many years prior, or the inclusion of TDP-43 in the current models. Together, our findings support the hypothesis that TDP-43 pathology in older persons affects a broader spectrum of behavior than previously recognized and that its impact extends beyond traditional aspects of cognitive function.

The acquisition of domain-specific knowledge not only requires traditional cognitive abilities but also reflects various social/behavioral skills, such as motivation, engagement, and goal-orientated behaviors. All of these skills work together to permit an individual to access, understand, and utilize information to promote better health-related behaviors and avoid adverse outcomes 6. We previously reported that lower literacy predicts subsequent age-related cognitive decline 3, and the development of MCI 9, 25 and Alzheimer’s dementia 12. In keeping with this, we and others show that TDP-43 pathology is important in the development of dementia and rate of cognitive decline 13, 17, 26. While it is well established that early behavioral changes occur in those diagnosed with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions, there is a growing body of evidence describing ‘Mild Behavioral Impairment’ as early personality or behavioral changes that precede MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia 27. Our findings are consistent with this notion, as they suggest that accumulation of TDP-43 pathology not only has a deleterious effect on memory but also other critical behaviors such as literacy that are essential for health and well-being.

From an anatomical standpoint, maintaining skills for adequate literacy function requires multiple complex neural networks from both cortical and subcortical brain structures to correctly process information. Progression of TDP-43 pathology in older persons largely involves multiple regions of the limbic system, including the amygdala, hippocampus, basal forebrain, and insular cortex 32. These brain regions are instrumental in registering complex social, cognitive, emotional, and environmental information, are sensitive to psychological factors 28, 29, and fundamental in functional connectivity patterns associated with literacy and decision making 15, 30, 31. TDP-43 pathology also involves neocortical brain regions including the anterior temporal lobe 14, and occipitotemporal 32 and orbitofrontal cortices 33, regions critical for language processing, comprehension 34, reading skills 35, and decision-making. Given the functional importance of these regions, it might be that TDP-43 pathology impairs a myriad of regional brain networks and pathways necessary for both cognitive and behavioral skills, including literacy function. In the present study, neocortical TDP-43, but not limbic TDP-43, appeared to be a particularly important driver of lower literacy in older adults. We have previously shown accumulation of TDP-43 pathology in the anterior temporal pole is earlier than the involvement of other neocortical regions, and is the most frequently involved neocortical region 14. Future studies are warranted to investigate the relationship between regional TDP-43 pathology and literacy across different neocortical stages.

This study has multiple strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate TDP-43 pathology with financial and health literacy data. Detailed neuropathological assessments to identify AD and TDP-43 pathology were completed, with a large proportion of post-mortem brains from older persons having both AD and TDP-43 pathology. Availability of this post-mortem data provides new insights regarding the behavioral clinical manifestations of TDP-43 pathology, independent of AD, in older persons. Furthermore, data came from two well-established community-based older persons who completed a detailed, validated battery of cognitive tests, and a standardized literacy assessment that has been previously adopted in a number of prior studies. Limitations of the present study are that the study sample was largely non-Hispanic white, and relatively highly educated; thus, these data may not be generalizable to the overall older adult population. A second limitation is that autopsy pathology data was only collected from one hemisphere, raising the possibility that unilateral pathologies were not identified. Third, due to the low numbers in the present study we only included distribution of cytoplasmic TDP-43 inclusions across 3-stages. Future studies addressing the relationship of literacy to the more fine-graded 5-stage of TDP-43 distribution, as previously described 14, will be important. Lastly, the current analyses are restricted to cross-sectional relation between TDP-43 and literacy. However, longitudinal assessments of literacy are ongoing, and will be essential in elucidating the neurobiological basis underlying literacy decline in future studies.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all the participants enrolled in the Rush Memory and Aging Project. We also thank the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center staff.

Funding sources: This study was funded by the following sources; P30AG010161, R01AG017917, R01AG15819, R01AG033678, R01AG034374, R01AG042210

Funding Disclosures: The study was supported by National Institute on Aging (grant number P30AG010161, R01AG017917, R01AG15819, R01AG033678, R01AG034374, R01AG042210)

Footnotes

Disclosures: No disclosures to report

References

- 1.Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Aging and Functional Health Literacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71:445–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serper M, Patzer RE, Curtis LM, et al. Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:1249–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Segawa E, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline impairs financial and health literacy among community-based older persons without dementia. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart CC, Yu L, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Correlates of healthcare and financial decision making among older adults without dementia. Health Psychol. 2018;37:618–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett JS, Bennett DA. The impact of health and financial literacy on decision making in community-based older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58:531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:723–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James BD, Wilson RS, Shah RC, et al. Association of Financial Literacy With Hospitalization in Community-dwelling Older Adults. Med Care. 2018;56:596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang MX, Stern Y. Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:680–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson RS, Yu L, James BD, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Association of financial and health literacy with cognitive health in old age. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2017;24:186–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L, Wilson RS, Han SD, Leurgans S, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Decline in Literacy and Incident AD Dementia Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons. J Aging Health. 2018;30:1389–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Contador I, Del Ser T, Llamas S, Villarejo A, Benito-Leon J, Bermejo-Pareja F. Impact of literacy and years of education on the diagnosis of dementia: A population-based study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2017;39:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu L, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Financial and Health Literacy Predict Incident Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia and Pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:1485–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James BD, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Trojanowski JQ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 stage, mixed pathologies, and clinical Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Brain. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nag S, Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology in anterior temporal pole cortex in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:33–018–0531–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han SD, Boyle PA, Yu L, et al. Financial literacy is associated with medial brain region functional connectivity in old age. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccolo LR, Merz EC, He X, Sowell ER, Noble KG, Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition, Genetics Study. Age-Related Differences in Cortical Thickness Vary by Socioeconomic Status. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nag S, Yu L, Capuano AW, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP-43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:942–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olney NT, Spina S, Miller BL. Frontotemporal Dementia. Neurol Clin. 2017;35:339–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Schneider JA. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:646–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and risk of AD in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62:1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1095–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, et al. TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han SD, Boyle PA, James BD, Yu L, Bennett DA. Poorer Financial and Health Literacy Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Aging Health. 2015;27:1105–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 immunoreactivity in AD modifies clinicopathologic and radiologic phenotype. Neurology. 2008;70:1850–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ismail Z, Aguera-Ortiz L, Brodaty H, et al. The Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C): A Rating Scale for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Pre-Dementia Populations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:929–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB. Neurobiological pathways linking socioeconomic position and health. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han SD, Boyle PA, Arfanakis K, et al. Financial literacy is associated with white matter integrity in old age. Neuroimage. 2016;130:223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broche-Perez Y, Herrera Jimenez LF, Omar-Martinez E. Neural substrates of decision-making. Neurologia. 2016;31:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:571–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolls ET, Grabenhorst F. The orbitofrontal cortex and beyond: from affect to decision-making. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:216–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mesulam MM, Rader BM, Sridhar J, et al. Word comprehension in temporal cortex and Wernicke area: A PPA perspective. Neurology. 2019;92:e224–e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mano QR, Humphries C, Desai RH, et al. The role of left occipitotemporal cortex in reading: reconciling stimulus, task, and lexicality effects. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:988–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]