Abstract

The need to understand the impact of war on military families has never been greater than during the past decade, with more than three million military spouses and children affected by deployments to Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Understanding the impact of the recent conflicts on families is a national priority, however, most studies have examined spouses and children individually, rather than concurrently as families. The Department of Defense (DoD) has recently initiated the largest study of military families in US military history (the Millennium Cohort Family Study), which includes dyads of military service members and their spouses (n > 10,000). This study includes US military families across the globe with planned follow‐up for 21+ years to evaluate the impact of military experiences on families, including both during and after military service time. This review provides a comprehensive description of this landmark study including details on the research objectives, methodology, survey instrument, ancillary data sets, and analytic plans. The Millennium Cohort Family Study offers a unique opportunity to define the challenges that military families experience, and to advance the understanding of protective and vulnerability factors for designing training and treatment programs that will benefit military families today and into the future. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: psychology, family, military, epidemiology, mental health, deployments

Introduction

At the turn of the century, the US military launched the largest study of service personnel in its history, the Millennium Cohort Study (Gray et al., 2002). This prospective epidemiologic study was serendipitously begun before the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, and designed to evaluate the effects of military service on the long‐term health and well‐being of US service members (Crum‐Cianflone, 2013). Shortly thereafter, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan began, and over the past decade more than 2.5 million service members have deployed in support of these operations, with over one million experiencing multiple deployments (data from the Defense Manpower Data Center [DMDC], 2012). The impact of the long and repeated deployments on service members' health and well‐being has been the subject of multiple studies (Hoge et al., 2004; Hoge et al., 2006; Milliken et al., 2007; Grieger et al., 2006; MHAT‐V, 2008), including within the Millennium Cohort Study, which has prospectively evaluated the impact of these military experiences on long‐term mental and physical health outcomes of service personnel (Crum‐Cianflone, 2013; Smith et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009; Jacobson et al., 2008; Wells et al., 2010).

During the past two decades, military service members have been more likely than ever to be married and have children (Department of Defense, 2010). As such, military families have also been touched by the recent conflicts, with an estimated three million dependents and two million children affected by the deployments to Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Department of Defense, 2010; Office of Secretary of Defense, 2012). Although families do not directly experience the combat or environmental exposures during deployments, they are at high risk for experiencing the impact of combat‐related injuries, including post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury, and other behavioral conditions among returning service members (Calhoun et al., 2002; Griffin et al., 2012; Manguno‐Mire et al., 2007; US Military Casualty Statistics, 2013; Ben et al., 2000). In turn, the support or distress with which families respond directly impacts the service members' health and well‐being (Tarrier et al., 1999; Solomon et al., 1988), and ultimately the fitness and readiness of the military force (Department of Defense, 2012).

Although much of the existing research suggests that exposure to deployments and war zone stressors are associated with negative sequelae including high rates of concurrent mental health problems (de Burgh et al., 2011; Mansfield et al., 2011; Mansfield et al., 2010; Lester et al., 2010; Eaton et al., 2008; White et al., 2011; Chandra et al., 2010; Flake et al., 2009), other research has also shown that many service members and their families are resilient (Wiens and Boss, 2006; Bonanno et al., 2012; Cozza et al., 2005). Hence, systematic documentation of both negative and positive outcomes associated with military experiences, along with detailed analyses of vulnerability and resilience factors will provide a foundation for informing the development of prevention strategies and documenting programmatic needs of current and future US military families.

Despite the fact that the impact of the recent wars on military families has been defined as a national priority, significant gaps in knowledge remain. In 2007, the Department of Defense (DoD) recommended the conduct of research studies on post‐deployment adjustments of family members, including children who were separated from their parent(s) due to deployment (Secretary of Defense, 2007; p. 11). The report declares, “Our ultimate goal is, as it has always been, to ensure that the health and well‐being of our military personnel and their families … .” This declaration is supported by other academic, professional, and military organizations identifying research on military families as a high‐priority issue (American Psychological Association, 2007; Siegel et al., 2013; US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, 2013). Although studies on military families have been conducted, most have examined spouses and children individually, rather than concurrently as families (Mansfield et al., 2011).

Overview of the Millennium Cohort Family Study

Based on recommendations for comprehensive, systemwide research on military families and with the success of the Millennium Cohort Study (n > 200,000 participants in the first four panels), the Family Study was designed to evaluate the interrelated health and well‐being effects of military service on families, including the service member, spouse, and children. The Family Study is a DoD‐sponsored study designed by a multidisciplinary team of investigators at the Naval Health Research Center (NHRC), Abt Associates, Duke University, and New York University, with survey operations conducted at NHRC. The initial study protocol was extensively peer reviewed by experts in the fields of military family research, longitudinal survey design and implementation, health outcomes research, and military organizational structure and functioning. An independent scientific review panel composed of academic researchers, DoD researchers and military service members, and Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) representatives provides advisement on the design and conduct of the study.

The Family Study includes both male and female spouses of active duty, Reserve, and National Guard personnel from all five service branches (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard) of the US military. Because the Family Study is nested within the Millennium Cohort Study, it provides exclusive data on a large cohort of service member–spouse dyads, providing the most comprehensive study of military families to date. As such, the Family Study is uniquely poised to provide strategic data to inform leadership and guide interventions to improve the lives of military families.

Family study objective

The Millennium Cohort Family Study's primary objective is to evaluate prospectively the associations between military experiences (including deployments) and service member readjustment on families' health and well‐being. Studying the health of military families in a large sample of service members surveyed pre‐ and post‐deployment allows for temporal sequence of associations that can be utilized to answer critical scientific, operational, and policy questions. These data can also be utilized in the development of training and clinical interventions that protect against and/or treat adverse health outcomes among both military spouses and children.

Study participants

During its first decade, the Millennium Cohort Study enrolled three large panels of service members (cumulative n > 150,000) using a complex probability sample design with the US military roster as the sampling frame. The three samples were designed to represent collectively all who served in the US military from 2000 moving forward. Enrollees are assessed at baseline and approximately every three years for a planned 67‐year period (Crum‐Cianflone, 2013).

Enrollment of military spouses for the Family Study was initiated within the most recent Millennium Cohort survey cycle (fourth panel, 2011–2013), in which a fourth panel representing military members with 2–5 years of service were invited to join the study, with the goal of enrolling approximately 60,000 new service members. Military service members were randomly selected from all service branches and components from the military roster in October 2010 provided by the DMDC. The cohort was oversampled for married and female service members to ensure adequate numbers of spouses, including male spouses, for enrollment into the Family Study. We estimated that more than half of the newly enrolled Millennium Cohort participants would be married, and that approximately 10,000 spouses of these service members would enroll in the Family Study.

Among the enrolled military spouses, we estimated that 50% would be married to a service member who had deployed to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan at least once, and the other half would be without deployment experiences. Because a subset of service members were assessed prior to deployment, this design will support between‐subjects comparisons (outcomes for spouses of deployed versus non‐deployed service members). We also anticipated that a sizeable proportion of the service members will deploy at some time after their baseline assessment, creating the opportunity for a prospective study of the impact of deployment on military families that supports within‐subjects comparisons (outcomes for spouses before versus after service member deployment). A sampling strategy supporting both kinds of comparisons substantially strengthens the ability to identify causal factors for both positive and adverse family outcomes.

Study methodology

Enrollment in the Family Study initially utilized a four‐step enrollment process: (1) invitation of a probability sample of military service members to participate in the Millennium Cohort Study, (2) referral of spouses to the Family Study among married new enrollees of the Millennium Cohort, (3) invitation of referred spouses to complete the Family Study survey online, and (4) enrollment of the spouse in the Family Study. Although there were notable strengths of this referral process (obtaining spousal contact information from the service member and secondary consent for his or her participation), there were limitations. The service member was offered a single opportunity to refer his or her spouse at the end of the Millennium Cohort survey, which may have resulted in lower than expected referral rates. In addition, because participation in the Family Study initially required agreement from the service member, there were concerns regarding potential referral biases. Thus, the study's survey methodologies were modified early in the data collection period to include spouses both referred by their service members as well as by direct invitation to join the study. Those invited directly to join must also have been married to a service member who enrolled in the Millennium Cohort study, but referral by the service member was not required for these spouses. In addition, the Family Study, which initially began as a web‐based survey, was expanded to include a paper version of the survey. Prior research documents that survey respondents may prefer one data collection mode over another, and that offering a second mode (e.g. paper survey) may reach different types of respondents and therefore may reduce response bias (Groves, 2006; Millar and Dillman, 2011; Dillman et al., 2009). A similar approach has been utilized in the Millennium Cohort Study.

The survey methods for the Family Study were modeled after the work of Dillman (Dillman et al., 2009) and designed to encourage all invited spouses to complete the survey to ensure a broad range of experiences were captured. Referred spouses received both postal mailings and e‐mails to encourage participation. Since e‐mail addresses for the sample of spouses invited directly to join the study were not available, an implementation method consisting of a mail‐only campaign was designed. This sequential postal approach involved six separate mailings conducted over a 10‐week period and consisted of (1) a card inviting the spouse to participate through a website link along with a pre‐incentive (picture frame magnet); (2) a follow‐up postcard reminder; (3) a sample of the survey, which highlighted questions from various sections of the survey and a pre‐incentive $5 gift card; (4) a letter encouraging participation endorsed by Deanie Dempsey, the wife of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; (5) a paper questionnaire with a postage‐paid return envelope delivered via express mail (e.g. Federal Express, US Postal Service Priority Mail); and (6) a postcard reminder. The first four mailings encouraged participation on the internet, while the fifth mailing introduced the option of completing a paper survey. In addition to the six postal mailing approach, when an e‐mail address was available (i.e. a service member referred his or her spouse and provided an e‐mail address), reminder e‐mails were sent that included a convenient link directly to the web survey. This strategy, referred to as “e‐mail augmentation” was designed to reduce participant burden associated with responding (Millar and Dillman, 2011). Mailings were discontinued when the participant enrolled in the study or declined to participate, or at the end of the survey period.

This sequential mailing approach was utilized for several reasons. First, we wanted to clearly communicate the value of the Family Study (e.g. follows families over time as they experience the unique challenges associated with military life) and its relevance to military spouses. Each mailing was designed to carry a unique message and was intended to reach different groups of spouses. Second, we communicated via e‐mail messages when possible and provided the option of a web‐based survey to reach a population that may be highly mobile due to frequent military relocations. Further, web‐based technology is associated with the advantages of reduced time and costs associated with processing paper surveys, and for implementing complex skip patterns and reducing erroneous responses. Third, instead of offering a simultaneous choice of survey response modes in our initial communications, which has been shown to have potential negative consequences on survey response rates (Dillman et al., 2008; Griffin et al., 2001), we offered a single choice at a time and utilized a carefully sequenced series of communications. Prior research has shown that using a paper response option late in the contact sequence may not only increase paper response, but also increase web response rates (Dillman et al., 2008; Messner and Dillman, 2011). We also tested during the study survey period an alternate six‐item postal mailing approach that offered only one mode for completion (paper); however, this approach was more costly and did not yield higher response rates.

Several additional strategic approaches were utilized during the study to enhance participation rates. The Family Study uses a logo, the “Family Tree,” on all e‐mails and postal mailings to make study communications easily recognizable. The oak tree was chosen to serve as a symbol of courage and strength, and to prime thoughts of family lineage. In order to mitigate concerns regarding the legitimacy of the research, approvals from the NHRC Institutional Review Board (NHRC 2000.0007), Office of Management and Budget (OMB Approval Number 0720‐0029), and a Report Control Symbol number (RCS Number DD‐HA(AR)2106) were provided on study materials and the study website. Finally, because of the sensitive nature of some of the questions on the survey, communications assured spouses of the confidentiality and security of the information provided. Particular emphasis was placed on assuring both participants of the Millennium Cohort and Family Studies that their spouses would not have access to their survey responses.

Because military families' experience changes over time and to maintain methodological consistency with the Millennium Cohort Study, spouses will be followed longitudinally (for 21+ years) and requested to complete a follow‐up survey approximately every three years. Follow‐up will continue even if their spouse separates from the service or their relationship status changes (i.e. separated, divorced, or widowed).

Study data: survey instrument and ancillary databases

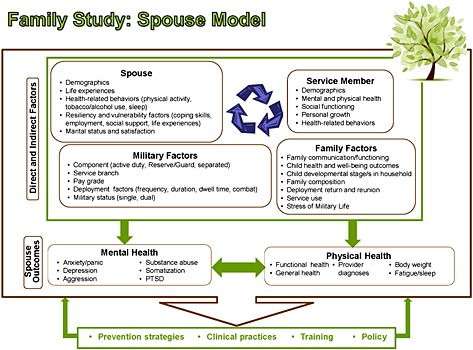

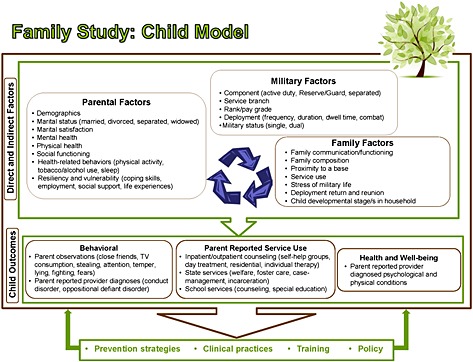

The Family Study Baseline Questionnaire comprises approximately 100 questions, some with multiple components and associated skip patterns. The specific questions within the survey are based on a conceptual model created with four main domains: (1) spouse physical health; (2) spouse mental health and adjustment; (3) spouses' reports of their children's mental/physical health and functioning; and (4) family functioning, and protective and vulnerability factors (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for the Millennium Cohort Family Study: spouse model.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model for the Millennium Cohort Family Study: child model.

The questionnaire is divided into 14 specific areas, allowing for the grouping of similar questions and time frames. The areas include the spouses' demographics, physical health, mental health, coping skills, life experiences, modifiable behaviors, military service (for dual military families), marital relationship, their service members' deployment, return and reunion experiences after deployment, their service members' behavior, military life, family functioning, and their children's’ health and well‐being. Information on the children is reported by the spouse and includes data on behavioral and emotional development at the level of the individual child as well as aggregate data of children's mental health and service use. Open text fields are also included in the survey to allow participants to share health and other concerns not covered by the survey. Follow‐up surveys will allow for longitudinal capture and temporal sequencing of the changing nature of the spouses' experiences (e.g. relocation, separation, deployment, parenthood) and health symptoms, and their trajectories over time. Similar to the Millennium Cohort Study, the Family Study survey instrument allows for modification over the years to address emerging concerns.

Standardized, scientifically validated instruments are incorporated into the survey because of their reliability and validity, and to enable future comparisons with other populations. Many of these instruments also mirror those contained within the Millennium Cohort Study to allow for direct comparability of measures between the service member and spouse. Examples of standardized instruments include the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36‐Item Health Survey for Veterans (SF‐36V), from which mental and physical component scores are calculated as a measure of functional health. The PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL‐C) and the Patient Health Questionnaire‐8 (PHQ‐8) are utilized to screen for PTSD and depressive disorder, respectively. Additional validated measures of alcohol use, sleep, eating disorders, childhood experiences, marital relationship, and family communication and satisfaction are included. Assessments of the children include components of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Table 1).

Table 1.

Standardized instruments embedded within the Millennium Cohort and Family Studies Baseline Survey

| Construct | Inventory |

|---|---|

| Physical, mental, and functional health | Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36‐Item Health Survey for Veteransa |

| Modules on common types of mental disorders: depression, anxiety, panic syndrome, somatoform symptoms, alcohol abuse, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating | Patient Health Questionnaireb |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | PTSD Checklist – Civilian Versiona |

| Alcohol problems | CAGE questionnairea |

| Sleep | Insomnia Severity Indexa |

| Adverse childhood experiences | Adverse Childhood Experiencesb, c |

| Marital satisfaction | Quality of Marriage Indexb, c |

| Family communication and satisfaction | Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scaleb |

| Behavioral screening questionnaire for ages 3‐ to 17‐year | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaireb, c |

Survey instrument present in both the Millennium Cohort Survey and the Family Study Survey.

Survey instrument currently present in the Family Study Survey.

Adapted version of the instrument was utilized.

In addition to the Family Study survey data, spouse responses can be linked to the service member's information, including physical, mental, and behavioral health as well as military‐related experiences collected as part of the Millennium Cohort Study survey. In addition to the subjective survey responses, the data can be linked to numerous official DoD data files including military and medical records (Table 2). These include medical care (medical diagnostic codes, vaccinations, and pharmaceutical prescriptions) used by the service member and spouse through the military treatment facilities or the military insurance program (TRICARE). Additionally, data on service members' deployments, occupations, injuries, environmental exposures, and other military events (e.g. disciplinary actions, promotion, and separation) can be investigated. For dual military families, spouses have the same data sets available as members in the Millennium Cohort Study (Table 2). Together, these data create the most robust research data set in existence to address the impact of military service experiences on the health of both service members and their families.

Table 2.

Complementary data sources

| Type of data | Source |

|---|---|

| Service member | |

| Service member physical, mental and behavioral health; military‐related experiences | The Millennium Cohort Study |

| Medical record data from military medical facilities worldwide and civilian facilities covered by the Department of Defense (DoD) insurance system (TRICARE) |

Standard Ambulatory Data Record (SADR) Standard Inpatient Data Record (SIDR) TRICARE Encounter Data (TED) |

| Immunization, deployment (location and dates), and contact data | Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) |

| Pharmaceutical data from military medical facilities and civilian pharmacies for medications paid for by TRICAREa | Pharmacy Data Transaction System (PDTS) |

| Service and medical data from time of enlistment to separation | Career History Archival Medical and Personnel System (CHAMPS) |

| Injury data from in theater | Joint Theater Trauma Registry (JTTR) and the Navy‐Marine Corps Combat Trauma Registry Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database |

| Total Army Injury and Health Outcomes Database (TAIHOD) | |

| Environmental Exposures | US Army Public Health Command |

| Links occupational codes between the military services and civilian counterparts | Master Crosswalk File from the DoD Occupational Conversion Index Manual |

| Health symptoms and perception, as well as exposure data | Pre‐ and Post‐Deployment Health Assessments (DD2795 and DD2796) |

| Medical status and resource utilization | Health Enrollment Assessment Review (HEAR) |

| Mortality data | Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES) mortality files, and National Death Index |

| Medical benefit eligibility and insurance, dates of service, military occupation and locations, centralized immunization data | Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS) |

| Spouse | |

| Medical record data from military medical facilities worldwide and civilian facilities covered by the DoD insurance system (TRICARE) | Standard Ambulatory Data Record (SADR) |

| Standard Inpatient Data Record (SIDR) | |

| TRICARE Encounter Data (TED) | |

| Pharmaceutical data from military medical facilities and civilian pharmacies which medications are paid for by TRICARE | Pharmacy Data Transaction System (PDTS) |

| Mortality data | Social Security Administration Death Master File |

| Children | |

| Data on pregnancies and birth outcomes (e.g. birth defects)a | Birth and Infant Health Registry |

| Medical record data from military medical facilities worldwide and civilian facilities covered by the DoD insurance system (TRICARE)b | Standard Ambulatory Data Record (SADR) |

| Standard Inpatient Data Record (SIDR) | |

| TRICARE Encounter Data (TED) | |

| Pharmaceutical data from military medical facilities and civilian pharmacies which medications are paid for by TRICAREb | Pharmacy Data Transaction System (PDTS) |

If child born during active duty service time.

Based on if consent for medical record review is provided.

Data analyses

Data analyses of the Family Study will focus on six main research objectives that provide the framework for utilizing the data to provide substantive findings to the DoD. These objectives include (1) evaluate the associations between service member deployment (e.g. combat exposure, deployment duration and frequency) and the health and well‐being of spouses and children; (2) determine the associations between service member readjustment issues (e.g. PTSD, anxiety, depression, alcohol misuse/abuse) and the health and well‐being of spouses and children; (3) examine factors related to resiliency (e.g. communication, psychological growth, social support, service use) and vulnerability (e.g. stress, adverse life events) that moderate the association between deployment experiences and service member readjustment issues, and the health and well‐being of spouses and children; (4) identify factors that are important for marital quality and family functioning (e.g. work/family balance, modifiable behaviors, communication); (5) examine trajectories of study outcomes over time and conduct methodological studies (as described later); and (6) evaluate the associations between spouse and child health and well‐being with service member health and military‐related outcomes. Analyses will involve a mix of univariate and multivariate statistics, including modern methods that take account of the complex sample design and the statistical dependence (clustering) inherent in longitudinal (repeated measures) data.

Methodological studies are planned to ensure that spouses enrolled in the Family Study are representative of the overall spouse population among military personnel with 2–5 years of service. As previously mentioned, survey methodologies were utilized to maximize participation and reduce response biases. Similar to the Millennium Cohort Study (Smith et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2007c; Littman et al., 2010), a series of methodological analyses will be conducted. These will include assessments of service member responders compared with non‐responders of the fourth panel of the Millennium Cohort Study; characteristics of spouses (and their service members) among enrollees in the Family Study compared with non‐enrollees; referred versus non‐referred spouses; and enrolled spouses compared with all spouses of military members with 2–5 years of service. Because the study sample consists of military service personnel and their families, data on demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), education level, occupation, and military service characteristics (e.g. rate/rank, branch, component), and number of children are available for comparison. Additional methodological studies will emulate those conducted by the Millennium Cohort Study to include assessments of paper versus web responders and early versus late responders during the survey cycle. In addition, the internal consistency of measures, and the reliability and validity of self‐reported data will be determined, including comparison of self‐reports with objective measures in official DoD records.

Dissemination of study findings

Study findings from the Family Study will be provided to the DoD and DVA, and can be utilized for the development of interventions and policies to improve the lives of military families. This study will provide critical information on the relationship between service members' military experiences and readjustment issues on the health and well‐being of military spouses and children. Additionally, study results will be communicated to the broader clinical and research communities as well as to our study participants through submission of manuscripts to peer‐reviewed publications, newsletters, and other study‐related communications. In addition, the Study's website (http://www.FamilyCohort.org) provides a list of presentations and aggregate data of the characteristics of the study participants to date, and will be updated periodically to include publications and new study findings. Social media (e.g. Facebook and Wikipedia) may also be utilized for future communications.

Significance of the Millennium Cohort Family Study

The Millennium Cohort Family Study represents the first study of its kind by providing critical data on the service member–spouse dyad over a 21+ year time period. Given the extended follow‐up of spouses over time, this study presents a distinct opportunity to evaluate both the long‐term effects of military life on families and the impact of future conflicts. Unlike most studies on military families, the Family Study longitudinally evaluates military spouses, service members (via the Millennium Cohort Study), and their children both during and after service time. Because many of the challenges of military service may only occur after separation, this study is poised to provide critical data regarding the ongoing needs of military families.

The Family Study is also unique in its ability to explore the impact of military service on important subpopulations, including Reserve and National Guard families, dual military families, and female deployers along with their male military spouses. Previous studies of spouses have largely been limited to a single military branch and/or the female spouses of male service members. Further, Reserve/National Guard families may experience unique challenges, including short notification prior to deployments, loss of civilian jobs, changes in medical coverage, and a relative lack of support resources compared with active duty families. Because of these differences, Reserve/National Guard families may be impacted by deployment and service member readjustment in ways that active‐duty families are not. Similarly, approximately 48% of married military women and 7% of married military men are in dual military marriages, which may present with challenges including prolonged separation and overlapping deployments (Department of Defense, 2010). Finally, as an increasing number of women serve in the military, it is important to evaluate the effects of maternal deployments on children, and examine male spouses in studies of family functioning in order to elucidate potential sex differences.

Conclusion

The past decade of conflicts highlights the importance of understanding the impact of war on military service members and their families. The Millennium Cohort Family Study represents the only comprehensive epidemiologic study of the health of military families that longitudinally evaluates >10,000 service member–spouse pairs over a 21+ year period. This study includes US military families across the globe from all service branches and components. Understanding the associations between service members' deployments and other military experiences on the health and well‐being of their families is critically important for the DoD, DVA, and society. Advances in the understanding of the challenges that military families experience along with protective and vulnerability factors will benefit military families today and into the future.

Declaration of interest statement

All authors report no conflicts of interest and no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the other members of the Millennium Cohort Family Study Team including Evelyn Davila, PhD; Raechel Del Rosario, MPH; Isabel Jacobson, MPH; Cynthia LeardMann, MPH; William Lee; Michelle Linfesty; Gordon Lynch; Hope McMaster, PhD; Toni Rush, MPH; Amber Seelig, MPH; Kari Sausedo, MA; and Steven Speigle, from the Deployment Health Research Department, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, California. The authors thank Dr Donald Dillman at Washington State University. In addition, the authors gratefully acknowledge the substantive and methodological contributions of Lisa Amaya‐Jackson, MD, MPH; Ernestine Briggs‐King, PhD; Ellen Gerrity, PhD; Robert Lee, MS; and Robert Murphy, PhD, from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. The authors thank all the professionals from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, especially those from the Military Operational Medicine Research Program, Fort Detrick, Maryland. The authors want to express their gratitude to the Millennium Cohort Family Study participants, without whom this study would not be possible.

This work represents report 13‐XX, supported by the Department of Defense, under Work Unit No. N1240. This research was conducted in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects (Protocol NHRC.2000.0007).

This study was been approved by the appropriate ethics committee /institutional review board and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Crum‐Cianflone N. F., Fairbank J. A., Marmar C. R. and Schlenger W. (2014), The Millennium Cohort Family Study: a prospective evaluation of the health and well‐being of military service members and their families, International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23, pages 320–330, doi: 10.1002/mpr.1446

References

- American Psychological Association (2007) Presidential Task Force on Military Deployment Services for Youth, Families, and Service Members: The Psychological Needs of U.S. Military Service Members and Their Families: A Preliminary Report, Washington, DC, American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ben A.N., Solomon Z., Dekel R. (2000) Secondary traumatization among wives of PTSD and post‐concussion casualties: distress, caregiver burden and psychological separation. Brain Injury, 14(8), 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G.A., Mancini A.D., Horton J.L., Powell T.M., LeardMann C.A., Boyko E.J., Wells T.S., Hooper T.I., Gackstetter G.D., Smith T.C. (2012) Trajectories of trauma symptoms and resilience in deployed US military service members: prospective cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(4), 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun P.S., Beckham J.C., Bosworth H.B. (2002) Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(3), 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A., Lara‐Cinisomo S., Jaycox L.H., Tanielian T., Burns R.M., Ruder T., Han B. (2010) Children on the homefront: the experience of children from military families. Pediatrics, 125(1), 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozza S.J., Chun R.S., Polo J.A. (2005) Military families and children during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychiatric Quarterly, 76(4), 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum‐Cianflone N.F. (2013) The Millennium Cohort Study: answering long‐term health concerns of US military service members by integrating longitudinal survey data with Military Health System records In Amara J., Hendricks A. (eds) Military Medical Care: From Pre‐deployment to Post‐separation, Abingdon, Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Burgh H.T., Fear N.T., Iversen A.C., White C.J. (2011) The impact of deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan on partners and wives of military personnel. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(2), 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense (2010) Report on the Impact of Deployment of Members of the Armed Forces on Their Dependent Children, October 2010. http://www.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/Report_to_Congress_on_Impact_of_Deployment_on_Military_Children.pdf [26 June 2013].

- Department of Defense (2012) Annual Report to the Congressional Defense Committees on Plans for the Department of Defense for the Support of Military Family Readiness, Fiscal Year 2012. http://www.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/FY2012_Report_MilitaryFamilyReadinessPrograms.pdf [26 June 2013].

- Dillman D.A., Smyth J.D., Christian L.M. (2009) Internet, Mail, and Mixed‐mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd edition, Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D.A., Smyth J.D., Christian L.M., O'Neill A. (2008) Will a mixed‐mode (mail/Internet) procedure work for random household surveys of the general public? Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, New Orleans, LA.

- Eaton K.M., Hoge C.W., Messer S.C., Whitt A.A., Cabrera O.A., McGurk D., Cox A., Castro C.A. (2008) Prevalence of mental health problems, treatment need, and barriers to care among primary care‐seeking spouses of military service members involved in Iraq and Afghanistan deployments. Military Medicine, 173(11), 1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flake E.M., Davis B.E., Johnson P.L., Middleton L.S. (2009) The psychosocial effects of deployment on military children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(4), 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray G.C., Chesbrough K.B., Ryan M.A.K., Amoroso P., Boyko E.J., Gackstetter G.D., Hooper T.I., Riddle J.R. (2002) The Millennium Cohort Study: a 21‐year prospective cohort study of 140,000 military personnel. Military Medicine, 167(6), 483–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger T.A., Cozza S.J., Ursano R.J., Hoge C., Martinez P.E., Engel C.C., Wain H.J. (2006) Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle‐injured soldiers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(10), 1777–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D.H., Fischer D.P., Morgan M.T. (2001) Testing an Internet response option for the American Community Survey. Paper presented at the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- Griffin J.M., Friedemann‐Sánchez G., Jensen A.C., Taylor B.C., Gravely A., Clothier B., Simon A.B., Bangerter A., Pickett T., Thors C., Ceperich S., Poole J., van Ryn M. (2012) The invisible side of war: families caring for US service members with traumatic brain injuries and polytrauma. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 27(1), 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves R.M. (2006) Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70, 646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge C.W., Auchterlonie J.L., Milliken C.S. (2006) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA, 295(9), 1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge C.W., Castro C.A., Messer S.C., McGurk D., Cotting D.I., Koffman R.L. (2004) Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson I.G., Ryan M.A., Hooper T.I., Smith T.C., Amoroso P.J., Boyko E.J., Gackstetter G.D., Wells T.S., Bell N.S. (2008) Alcohol use and alcohol‐related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA, 300(6), 663–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester P., Peterson K., Reeves J., Knauss L., Glover D., Mogil C., Duan N., Saltzman W., Pynoos R., Wilt K., Beardslee W. (2010) The long war and parental combat deployment: effects on military children and at‐home spouses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(4), 310–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman A.J., Boyko E.J., Jacobson I.G., Horton J., Gackstetter G.D., Smith B., Hooper T., Wells T.S., Amoroso P.J., Smith T.C., Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2010) Assessing nonresponse bias at follow‐up in a large prospective cohort of relatively young and mobile military service members. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manguno‐Mire G., Sautter F., Lyons J., Myers L., Perry D., Sherman M., Glynn S., Sullivan G. (2007) Psychological distress and burden among female partners of combat veterans with PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(2), 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A.J., Kaufman J.S., Marshall S.W., Gaynes B.N., Morrissey J.P., Engel C.C. (2010) Deployment and the use of mental health services among U.S. Army wives. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(2), 101–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A.J., Kaufman J.S., Engel C.C., Gaynes B.N. (2011) Deployment and mental health diagnoses among children of US Army personnel. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(11), 999–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Advisory Team (MHAT‐V) (2008) Operation Iraqi Freedom 06‐08: Iraq Operation Enduring Freedom: Afghanistan. http://www.armymedicine.army.mil/reports/mhat/mhat_v/MHAT_V_OIFfandOEF-redacted.pdf [26 June 2013].

- Messner B.L., Dillman D.A. (2011) Surveying the general public over the Internet using address‐based sampling and mail contact procedures. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), 449–452. [Google Scholar]

- Millar M.M., Dillman D.A. (2011) Improving response to web and mixed mode surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(2), 249–269. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken C.S.M., Auchterlonie J.L.M., Hoge C.W. (2007) Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq War. JAMA, 298(18), 2141–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Secretary of Defense (2012) Demographics 2011: Profile of the Military Community, Washington, DC, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Secretary of the Defense (2007) Report to Congress: The Department of Defense Plan to Achieve the Vision of the DoD Task Force on Mental Health, Washington, DC, Department of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel B.S., Davis B.E., and the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Section on Uniformed Services . (2013) Health and mental health needs of children in US military families. Pediatrics, 131, e2002–e2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B., Smith T.C., Gray G.C., Ryan M.A.K., Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2007a) When epidemiology meets the Internet: Web‐based surveys in the Millennium Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166(11), 1345–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B., Wingard D.L., Ryan M.A., Macera C.A., Patterson T.L., Slymen D.J. (2007b) U.S. military deployment during 2001–2006: comparison of subjective and objective data sources in a large prospective health study. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(12), 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B., Wong C.A., Smith T.C., Boyko E.J., Gackstetter G.D., Ryan M.A.K.; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2009) Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population‐based study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170(11), 1433–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.C., Jacobson I.G., Hooper T.I., Leardmann C.A., Boyko E.J., Smith B., Gackstetter G.D., Wells T.S., Amoroso P.J., Gray G.C., Riddle J.R., Ryan M.A., Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2011) Health impact of US military service in a large population‐based military cohort: findings of the Millennium Cohort Study, 2001–2008. BMC Public Health, 11, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.C., Ryan M.A.K., Wingard D.L., Slymen D.J., Sallis J.F., Kritz‐Silverstein D. (2008) New onset and persistent symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ, 336(7640), 366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.C., Smith B., Jacobson I.G., Corbeil T.E., Ryan M.A., Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2007c) Reliability of standard health assessment instruments in a large, population‐based cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(7), 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z., Mikulincer M., Avitzur E. (1988) Coping, locus of control, social support, and combat‐related posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(2), 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N., Sommerfield C., Pilgrim H. (1999) Relatives' expressed emotion (EE) and PTSD treatment outcome. Psychological Medicine, 29(4), 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (2013) Strategic Communication Plan. Military Operational Medicine Research Program. https://momrp.amedd.army.mil/publications/MOMRP2.pdf [1 June 2013].

- US Military Casualty Statistics (2013) Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom. Congressional Research Service, CRS Report for Congress, February 5, 2013. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf [26 June 2013].

- Wells T.S., LeardMann C.A., Fortuna S.O., Smith B., Smith T.C., Ryan M.A., Boyko E.J., Blazer D., Millennium Cohort Study Team . (2010) A prospective study of depression following combat deployment in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health, 100(1), 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C.J., de Burgh H.T., Fear N.T., Iversen A.C. (2011) The impact of deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan on military children: a review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(2), 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens T.W., Boss P. (2006) Maintaining family resiliency before, during, and after military separation In Castro C.A., Adler A.B., Britt T.W. (eds) Military Life: The Psychology of Serving in Peace and Combat, Volume 3: The Military Family. The Military Life, pp. 13–38, Westport, CT, Praeger Security International. [Google Scholar]