Abstract

Health promotion programmes for patients with severe mental illness (HPP) are not uniformly evaluated. We discuss the evaluation of HPP in theory and practice, as a prerequisite for future uniform evaluation.

We explored the expected outcome and mechanism of HPP in the current literature. Based on this theoretical exploration we selected measures assessing the expected outcome and mechanism in current practice. The individual properties of these measures were described.

Based on our theoretical exploration the outcome of HPP can be expressed in several aspects of health. Health can be improved through several mechanisms. In the current evaluation of HPP only some of the expected outcomes were evaluated. The measures used for evaluation were not all representative for the constructs they should assess.

Important aspects of HPP are currently not evaluated, based on a comparison between our theoretical exploration of expected outcome and mechanism and current practice. Additionally, not all measures in use are suitable for evaluation of HPP. Therefore, development and identification of suitable measures is necessary. Our framework offers valuable directions for the development of such measures and the future evaluation of HPP. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: mental disorders, health services, evaluation studies, health improvement

Introduction

The somatic health status of people with severe mental illness (SMI) is worse when compared to the somatic health status of the general population, and this divergence has increased over the last decades (De Hert et al., 2011b; Saha et al., 2007). This reduced somatic health tendency has multiple interlinked causes, which are potentially reversible (De Hert et al., 2011b; Robson and Gray, 2007; Wildgust and Beary, 2010). Mental health care providers have initiated various health promotion programmes for patients with SMI (HPP) (O'Brien et al., 2013) to improve the somatic health (Happell et al., 2012; O'Brien et al., 2013; Tranter et al., 2012; van Hasselt et al., 2013). Improving somatic health leads to a potential improvement of experienced well‐being as well (Kwekkeboom and van Weert, 2008).

Randomized studies of HPP have evaluated the results effects of health education, exercise, smoking cessation and changes in the health care organization (van Hasselt et al., 2013). Although the anticipated outcomes of these HPP overlap, these programmes are not evaluated uniformly. The evaluations were performed with various different measures and they evaluated many different aspects of these HPP. The diversity in evaluation methods hampers comparisons between programmes, in particular on effectiveness, and therefore evidence‐based choices on implementation of HPP cannot be made (van Hasselt et al., 2013). For future comparisons of HPP it is necessary to evaluate uniformly.

As a prerequisite for future uniform evaluation this exploratory overview aims to describe and discuss the evaluation of HPP in theory and practice. Firstly, we developed a theoretical exploration of all expected outcomes and mechanisms of HPP. Secondly, we assessed the properties of measures currently used for evaluation of HPP.

Methods

For clarity we start with defining the terms we use in this manuscript in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of terms, in order of appearance in the manuscript

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Outcome | The consequences of the intervention; that which “comes out” of it (Øvretveit, 1998). |

| Conceptual framework | A model of interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon or phenomena (Jabareen, 2009). |

| Mechanism | The expected factor or process that causes the outcome, similar to the likely process of change (Craig et al., 2008). |

| Target | The part or whole of a person which the intervention aims to effect (Øvretveit, 1998). |

| Mechanism measure | A measure to assess whether a specific mechanism took place in the target person. |

| Outcome measure | A measure of an important expected effect of the intervention on the target person (Øvretveit, 1998). |

| Domain | A group of measures assessing similar constructs. |

Theoretical exploration of potential outcome and mechanism of HPP

To enable exploration of the expected outcome of HPP, we defined improved health as the ultimate outcome of HPP. Improved health can be achieved either by preserving a health status that would have deteriorated without intervention or by improving current and future health states. In order to detect improvement, an understanding of the situation without intervention is necessary. Therefore we start by developing a conceptual framework of reduced health in patients with SMI. Any change in this development of reduced health can subsequently be labelled as outcome.

A Medline search was performed searching for overviews on potentially modifiable causes of physical illness and/or reduced somatic health in patients with SMI influencing healthy life expectancy. The search terms included: mental disorder, health status and physical. Based on the findings, additional searches were performed aimed at other diseases related to a specific SMI risk factor, or other risk factors specific for diseases in SMI. This information was condensed to form a conceptual framework describing determinants of disease related to outcome of HPP.

Evaluation of a mechanism in HPP is only sensible, if it is theoretically plausible to get an outcome through that specific mechanism. We conceptualized several potential mechanisms of interventions, from the types of interventions identified in our systematic review (van Hasselt et al., 2013). The theoretical exploration of mechanism consists of an exploration of the evidence that these specific mechanisms are related to a specific outcome. Therefore, a second Medline search was performed to explore the theoretical plausibility of these mechanisms. The search terms included: a description of the mechanism (e.g. smoking) and the likely outcome (e.g. cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus).

Selection and discussion of currently used measures

We present an explorative overview of the properties of measures assessing outcome and mechanism currently used in HPP evaluation. The selection of measures was based on our previous systematic review (van Hasselt et al., 2013). This systematic review was focused on the evaluation of randomized interventions directed toward improving somatic health for patients with SMI. Twenty‐two original studies were included, the different interventions were grouped based on their descriptions in types. The outcome measures used were grouped in domains based on comparable measures. Next to the evaluation of outcome and mechanism, domains evaluating costs, psychiatric symptoms and process factors were described.

For this exploration of mechanism and outcome measures, a Medline search was performed on the characteristics of all the included outcome measures. This search focused on their ability to measure the elements they were designed to measure, suitability for use in patients with SMI and ability and if necessary evidence on responsiveness, as well as the ability to be used as parameters to distinguish differences in outcome over time. The search terms included: the name of the measure, validity, responsiveness, mental disorders.

Results

Theoretical exploration of potential outcome

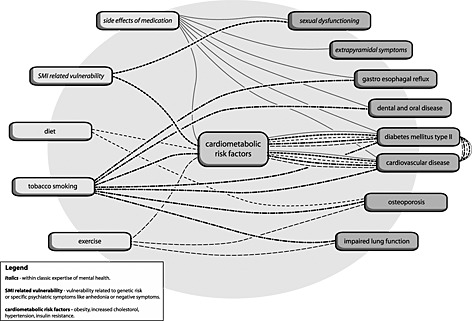

Based on the current evidence for modifiable risks on potentially modifiable causes of physical illness and/or reduced somatic health in patients with SMI we developed a cross table of information describing risk factors and health states (Table 2). Based on this cross table we designed our conceptual framework for outcome (Figure 1). This was constructed as a structural model, presenting the course of development of reduced somatic health in patients with SMI. The different types of lines are related to the different risk factors. Changes in this development can be marked as outcome. Even though determinants such as tobacco smoking are not exclusive for SMI patients, the addition of these on top of their specific vulnerability and side effects of medication is exclusive for these patients. Cardio metabolic diseases are main causes of death in populations with SMI (De Hert et al, 2011b). Therefore, the importance of cardio metabolic risk factors is stressed with their central position in the structural framework. This position emphasizes the possibility to assess this important intermediate stage between health and disease. As this framework describes the development of reduced somatic health, positive health effects of medication are not included.

Table 2.

References for conceptual framework for outcome

| Side effects of medication | SMI related vulnerability | Diet | Tobacco smoking | Exercise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardio metabolic risk | Robson and Gray, 2007; Goff et al., 2005 |

Robson and Gray, 2007 |

Robson and Gray, 2007; de Hert et al., 2011b | Robson and Gray, 2007; Goff et al., 2005 |

Robson and Gray, 2007 |

| Sexual dysfunction | Robson and Gray, 2007; de Hert et al., 2011b; Malik, 2007 | de Hert et al., 2011b; Malik, 2007 | — | — | — |

| Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) |

Sadock et al., 2009 |

— | — | — | — |

| Gastroesophageal GE |

Mookhoek et al., 2005 |

— | — |

Mookhoek et al., 2005 |

— |

| Dental/oral | Robson and Gray, 2007; de Hert et al., 2011b | — | — |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

— |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2 | Robson and Gray, 2007; Goff et al., 2005 | de Hert et al., 2011b; Goff et al., 2005 |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

Chang, 2012 |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

| Cardiovascular disease (CVD) |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

de Hert et al., 2011b |

| Osteoporosis |

Crews and Howes, 2012 |

— |

Crews and Howes, 2012 |

Crews and Howes, 2012 |

Crews and Howes, 2012 |

| Impaired lung function | — | — | — | Robson and Gray, 2007; de Hert et al., 2011b |

Garcia‐Aymerich et al., 2007 |

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for outcome.

Theoretical exploration of potential mechanism

Based on our systematic review, the following types of mechanisms were used in randomized HPP: exercise, improving diet, smoking cessation or reduction, early detection and treatment of disease and change in health care provision. Per type of mechanism, a brief description is presented regarding the potential influence on health status in the following sections.

Exercise

Physical activity has a beneficial effect on the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis (Warburton et al., 2006a). With or without weight loss exercise has a beneficial effect on risk factors for cardiovascular disease: diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) and glucose (Kesaniemi et al., 2001; Shaw et al., 2006). It is still unclear whether physical activity as such leads to changes in health or physical fitness is the mediating factor. Physical fitness and physical activity are both independently related to cardiovascular mortality (Myers et al., 2004). For weight loss, through any method, there is a positive correlation between the magnitude of sustained weight loss and the long‐term improvement in all components of the metabolic syndrome (Ferland and Eckel, 2011). Furthermore, weight loss reduces the risk of developing diabetes mellitus (DM). For patients with type 2 DM, the regulation of blood glucose levels improved with weight loss (Aucott et al., 2004).

Improving diet

Changing diet can induce health benefits, including the benefits of weight loss. Apart from weight loss, the risk of developing cardiovascular disease decreases by changing the patient's diet by either reducing the levels of, for instance, fat and sodium or increasing the intake of products like fruit and vegetables (Brunner et al., 2007).

Smoking cessation or reduction

Smoking cessation reduces the incidence of cardiovascular and coronary heart disease (Wu and Sin, 2011). Smoking cessation diminishes the loss of pulmonary capacity in patients with mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Furthermore, it reduces the risk of COPD progression as well as the risk for lung cancer and cardiovascular disease (Godtfredsen and Prescott, 2011). Smoking cessation can also lead to reduced risks in periodontal health in comparison to persistent smokers (Warnakulasuriya et al., 2010). Among individuals who smoked 15 or more cigarettes per day, smoking reduction reduces the risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular risk factors (Eliasson et al., 2001; Godtfredsen et al., 2005).

Early detection

Early detection is used to improve healthy life expectancy by detecting asymptomatic precursor states of the disease. However, this holds true only when true preventive treatment of these complications is possible. Presenting an overview of the effects of early detection of each disease was not possible. Therefore, we limited ourselves to the early detection and treatment of DM, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. The effect of DM screening and following intensive treatment to reduce HbA1c as a treatment strategy for all individuals is currently debated (Koshizaka et al., 2012). What remains is that screening and early treatment leads to reduction of potentially lethal complications in those whose diabetes is detected early and to the detection of a group of patients at high risk for developing diabetes (Rahman et al., 2012). Osteoporosis screening can potentially reduce fractures and related morbidity and mortality. The effect of screening has been assessed for groups at risk for developing osteoporosis. Early detection had no effects on fracture and related morbidity (Laliberte et al., 2011). Reducing cholesterol can reduce the five‐year incidence of major coronary events, coronary revascularization, and stroke (Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators, 2012). The reduction of cardiac incidents is even greater in persons with a history of coronary heart disease, than in persons without a disease history (Baigent et al., 2005). Lowering blood pressure leads to a reduction of stroke and coronary heart disease when used as primary and secondary prevention (Chalmers and Chapman, 2001; Law et al., 2003).

Health care organization changes

Organizational changes to improve the health care system focus mainly on coordination of care for individual patients, improving inter professional communication within one department or communication between departments of health care. In our selection of randomized studies no evaluation of health screening was present. Coordination of care or enhancing a multi‐disciplinary team with a specialist, e.g. a pharmacist, has been studied in patients with multi‐morbidity. The limited results, mainly in elderly, suggest that these interventions have mixed effects but show a tendency to improve prescribing and medication adherence (Smith et al., 2012). The evidence for implementing multi‐disciplinary meetings or multi‐disciplinary educational programmes is scarce and based on very different health care settings. No conclusions can be drawn yet on this subject (Reeves et al., 2008; Zwarenstein et al., 2009). Shared care is based on an increased collaboration of primary and specialist care. The evidence of shared care is based on short‐term follow‐up and relatively few studies. Up until now, only improved prescribing is a consistent outcome of these studies (Smith et al., 2007).

Selection of domains

Five domains for outcome evaluation and five domains for mechanism evaluation assessed elements of the conceptual framework (Tables 3 and 4). The domains evaluating outcome assessed cardio‐metabolic risk factors and side‐effects of medication. Furthermore general functioning, general health and quality of life (QoL) were also classified as outcome evaluation because they were presented as concepts directly relating to health. The domains evaluating mechanism assessed; diet, exercise and tobacco smoking. Furthermore, adherence to professional guidelines and self‐efficacy were also classified as mechanism evaluation because they were possible facilitators of all mechanisms of the framework.

Table 3.

Outcome evaluation, domains and measures

| Domain | Subdomain | Included measures | Short description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardio‐metabolic risk factors | Grouped | Framingham | Risk score is based on age, blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, cholesterol and HDL to predict cardiovascular risk (Druss et al., 2010) |

| NCEP ATP III | Criteria for the assessment of cardiometabolic risk based on obesity, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, blood pressure and impaired fasting glucose (Druss et al., 2010). | ||

| Obesity | BMI | Body mass index, relation between weight and height (Snijder et al., 2006). | |

| Skinfold | Assesses body fat by determining the thickness of a specific skin fold (Snijder et al., 2006). | ||

| Percentage weight increase | Weight increase as a percentage of base line weight (Snijder et al., 2006). | ||

| Waist circumference | Measure of the waist circumference (Snijder et al., 2006). | ||

| Waist–hip ratio | Ratio between waist and hip‐circumference (Snijder et al., 2006). | ||

| Hypertension | Sphygmanometric blood pressure | Sphygmanometric assessment of systolic and diastolic blood pressure. | |

| Lipids | HDL ratio | The ratio of HDL to LDL cholesterol. | |

| Lipid profile | Assessment of cholesterol and HDL, LDL and triglycerides. | ||

| Total cholesterol | Total cholesterol serum level. | ||

| Insulin resistance | HbA1c | Assess the glycosylated haemoglobin which reflects elevated blood glucose levels during the preceding weeks (Waugh et al., 2007). | |

| Fasting glucose | Assesses the glucose in an eight hour fasting state (Waugh et al., 2007). | ||

| Side‐effects of medication | AIMS | Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale assesses dyskinesia by means of seven items, rated on a severity scale which assess abnormal movements in various anatomical locations (Gharabawi et al., 2005). | |

| Webster scale | A clinical rating scale in which each of the following parkinsonian signs are rated for severity (Webster, 1968); bradykinesia of hands, rigidity, posture, gait, upper‐extremity swing, tremor, fades, speech and self‐care. | ||

| General health | 1‐item rating scale | Rating on a Likert scale of current physical health. | |

| Basic health screening | Basic health screening questionnaire | ||

| SF‐36 | Quantifies health in eight health concepts, which can be summarized to physical and mental health and well‐being (Ware and Sharebourne, 1992). | ||

| SCL‐90 | Assesses multiple domains of psychiatric symptoms and it includes items on physical health. SCL 90 is aimed at measuring distress related to these symptoms (Olsen et al., 2004). | ||

| Quality of life | MANSA | MANSA contains 16 questions, investigating objective quality of life and satisfaction with life as a whole, job, financial situation, friendships, leisure activities, accommodation, personal safety, people that the person lives with, family and health. Satisfaction is rated on a seven‐point scale (Bjorkman and Svensson, 2005). | |

| SF‐36 | SF‐36 quantifies health in eight health concepts, which can be summarized to physical and mental health and well‐being (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). | ||

| QoLI | Lehman quality of life (QoL) interview, a structured self‐report interview, on patients’ ratings of their QoL. The interview provides a broad based assessment of the objective and subjective QoL in several life areas, including living situation, family relations, social relations, daily activities, finances, safety and legal problems, work and school and health (Lehman et al., 1993). | ||

| WHOQoL B | Consists of a self‐report list of 26 items on four domains; physical health, psychological, social relations and environment (Skevington et al., 2004) | ||

| General functioning | GAF | Global assessment of functioning from DSM is a 0–100 score filled out by a clinician on the patient's overall level of functioning at a particular point in time (Soderberg et al., 2005) | |

Table 4.

Mechanism evaluation, domains and measures

| Domain | Included measures | Short description |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | DINE | Assesses daily fat and fibre intake (Roe et al., 1994). |

| Mizes | A 24‐item self‐report instrument designed to assess cognitions associated with anorexia nervosa (Osman et al., 2001). | |

| Exercise | Borg | Generally used measure to evaluate exertion at a certain exercise. |

| Exercise recall tests | Different tests were used to assess the retrospective assessment of exercise. the 13‐item patient activation questionnaire, the active Australia questionnaire, Baecke questionnaire, the behavioural risk factor surveillance on physical activity, the Blair seven‐day physical activity recall and the GODIN questionnaire on exercise | |

| Exercise tolerance tests | There are tests directly assessing the exercise tolerance for walking or cycling; the incremental shuttle walk test, the estimated maximal oxygen consumption, the graded exercise tolerance test (inter alia Franz test). The outcomes reported from these tests differ from heart rate/exercise intensity in watts to maximal capacity (VO2max). | |

| pedometer | Electronic device used to assess the daily activity. | |

| Strength | Tests were used assessing strength–maximal dynamic strength and maximal sit up endurance. | |

| Tobacco smoking | Biological smoking markers | Biological markers of tobacco smoking cessation (point prevalence abstinence) were used; exhaled CO and cotinin measures in saliva. |

| Nicotine dependence | Nicotine dependence was assessed with the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence and the Shiffman | |

| Jarvik nicotine withdrawal scale, 11 item readiness and motivation to quit smoking | ||

| Smoking abstinence | 12 months abstinence and continuous abstinence were assessed next to time to relapse after cessation, reduction of >50% of amount of smoking. | |

| Adherence to professional guidelines | Eligible versus obtained services | The proportion between eligible versus obtained services in healthcare |

| Quality indicators | Quality indicators for preventive medicine, advised services for this high risk population. These quality indicators were derived from a guideline for the general public (DiGuiseppi et al., 1996) advising screening for amongst others cardiovascular health and metabolic health. | |

| Self‐efficacy | Health‐related self‐efficacy | Assessment of health‐related self‐efficacy |

| Self‐efficacy for exercise | Assessment of self‐efficacy for exercise |

Properties of outcome measures

Cardio‐metabolic risk factors

The outcome measures in this domain can be subdivided into different types: grouped risk factors and single outcome measures. Grouped risk factors were defined as an individual risk estimation based on a selection of cardio metabolic risk factors. National Cholesterol Education Programme (NCEP) ATP III predicts less accurate cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than the Framingham risk score and fasting glucose is at least as good as the metabolic syndrome in predicting diabetes mellitus (Reaven, 2011). Evidence shows that Framingham underestimates the risk of cardio‐metabolic morbidity and mortality, especially in the group of patients with severe mental illness (De Hert et al., 2009). For the estimation of body fat body mass index (BMI) is a good estimation of the amount, but gives no information on its localization. Waist circumference, as a proxy for visceral fat, enables a more accurate individual risk estimation than only BMI. There is no evidence that waist–hip ratio or skin fold measurement is more accurate than waist circumference for risk estimation (Snijder et al., 2006). Waist circumference is strongly related to other cardiovascular risk factors (van Dijk et al., 2012). Finally, there is no clear basis for the cut‐off point, “Increase in body weight of >7%” after the start of a treatment (Jayaram et al., 2006).

For the other single cardio metabolic risk factors, when presenting blood pressure, it is often not clear whether investigators measured this only once or multiple times during a session and which assessment is reported. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend for the diagnosis of hypertension to perform ambulatory or home blood pressure assessment after an incidental measurement of 140/90 mmHG (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, NICE, 2011). To assess the cardiovascular risk total cholesterol, as well as HDL cholesterol should be measured according to current NICE guidelines. For screening on insulin resistance, related to an increased cardiovascular risk and risk on diabetes, it is stated that there is no “best” test. Fasting glucose does not identify patients with impaired glucose tolerance, an important risk factor for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. HbA1c is presented as the best option. An additional advantage of HbA1c is that it can be used to monitor treatment response (Waugh et al., 2007).

Side‐effects of medication

Extrapyramidal symptoms consist of a cluster of symptoms including parkinsonism, dystonia, dyskinesia and akathisia. To our knowledge, no studies have been done on the responsiveness of observed extra pyramidal symptom scales. The AIMS scale has been widely used to assess dyskinesia (Dean et al., 2006). For robust information a combination of instrumental measurement and a clinical rating is advised, especially in long‐term trials (Dean et al., 2004; Loonen and van Prang, 2007).

General functioning

The domain of general functioning was conceptualized as those outcome measures that are related to the impairments or possibilities in the ability to and real execution of various tasks of day‐to‐day living. Global assessment of functioning (GAF) ratings made by an individual rater can be used to measure changes and outcomes at the group level (Soderberg et al., 2005).

Quality of life (QoL)

QoL is conceptualized by us as a domain of outcome measures that assess the impact of diseases and symptoms on the experienced possibility to live your life in health according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criterion of health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well‐being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The SF‐36, MANSA and QoLI were validated in patients with SMI (Bjorkman and Svensson, 2005; Coons et al., 2000; Norholm and Bech, 2007). Also the WHOQoL B was validated in patients with SMI and this scale was shown to be responsive to changes over time (Kao et al., 2011; Mas‐Exposito et al., 2011). These outcome measures are all generally used and accepted to represent QoL.

General health

The domain general health has been conceptualized by us as an overall estimate of health and disease. As such it can be hypothesized as a complex measure of variable symptoms and specific disease states. SF‐36 and SCL‐90 are rating scales that cover multiple health aspects, and are described by some authors as outcome measures of general health. For the “1‐item rating” and the “basic health screening” no information was present on representativeness for the concept general health and their validity. All currently used general health scales are based on self‐assessment of the severity and impact of the disease state. Therefore these outcome measures are a relative value of the experienced burden for an individual at a certain time point. This use of individual assessment of burden of diseases generates an overlap with self‐rated QoL outcome measures. Although they overlap, general health should be regarded as a different outcome domain than QoL (Hewitt, 2007) . Therefore the currently used outcome measures do not assess our construct of general health.

Properties of mechanism measures

Exercise

We conceptualized mechanism measures of exercise as measures assessing actual exercise or constructs strongly related to exercise. The ability to measure “responsiveness”, the change in exercise level over time was tested for physical activity recall tests in a systematic review including the tests used for interventions to improve somatic health in SMI. The authors concluded that only two of the 85 questionnaires were analysed for responsiveness, these two tested questionnaires had poor responsiveness. Furthermore, for all questionnaires the information on content validity was essentially lacking (van Poppel et al., 2010). Even results of diverse questionnaires on prevalence of exercise in minutes cannot be compared (Brown et al., 2004).

Physical fitness measurements can evaluate aerobic fitness, anaerobic fitness and muscoloskeletal fitness. Unfortunately, it is unclear how these different types of fitness are related to health (Warburton et al., 2006b). Research has been primarily focused on the relation between aerobic fitness and mortality. Furthermore, there is no clear relation between strength measures and cardiovascular mortality. Therefore we will limit ourselves to aerobic fitness evaluation. An improvement of aerobic fitness is associated with reduction in total mortality and cardiovascular risk (Lee et al., 2011). The gold standard for measuring aerobic physical fitness is a graded exercise test during which oxygen consumption (VO2), carbon dioxide production, and pulmonary ventilation are measured (Mossberg and Fortini, 2012). The required equipment for this evaluation limits the large scale use of this measurement. Aerobic fitness intensity, can also be expressed in metabolic equivalents (MET), this is strongly related to all causes of mortality (Kodama et al., 2009). These MET values can be calculated from different ergometer and treadmill protocols (Kodama et al., 2009). Using MET values outcomes can be presented showing the achieved peak intensity of fitness, or prolonged duration of fitness at a certain intensity. It should be noted, however, that possibly the standard set of MET values for specific exercise should be adapted when used for the population of patients with SMI with more obesity and comorbidity (Woolf‐May and Ferrett, 2008). The Borg exercise scale can also be used to assess the moment of maximal exercise, but is not an assessment of physical capacity per se (Lear et al., 1999). Pedometers are small devices used to assess the amount of steps taken in daily activity and sports. Pedometer scores have been related to cardiovascular fitness and weak to moderate associations were found with exercise tolerance tests (Tudor‐Locke et al., 2002).

Diet

We conceptualized mechanism measures of diet as measures assessing actual diet or constructs strongly related to diet choices and habits. In evaluating dietary intake it is preferable to use biomarkers (Brunner et al., 2007) but these are complicated to use in day‐to‐day practice. To our knowledge, there are no studies on the validity of using food frequency questionnaires or registration of diet for 24 hours for people with SMI, therefore no advice on future use is possible. Cognitions related to weight and diet can be assumed to influence diet, but no clear evidence is present to support this. Therefore, cognitions should not be used as single outcome for diet, because their relation with the actual diet and thus their relation with influence on somatic health is not evident.

Tobacco smoking

We conceptualized mechanism evaluation of tobacco smoking as measures assessing actual tobacco smoking or constructs strongly related to tobacco smoking. It should be noted that smoking cessation is the final endpoint of different phases in a trajectory starting with motivation to quit. Effects of interventions leading to progression in this trajectory are missed if the focus is only on abstinence. Therefore, intention to quit, nicotine dependence, withdrawal symptoms and smoking rate are useful measures to analyse effects caused by the intervention possibly leading to future smoking cessation (Baker et al., 2011). Because these measures cannot yet predict future smoking cessation and therefore health benefits, they should not be used as a single outcome. Further interpretation of their value as implementation measures is beyond the scope of this article.

The prolonged abstinence is based on biological markers; exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) is less specific for measuring tobacco exposure than urine cotinine (Benowitz, 1999). Prolonged abstinence can also be assessed based on self‐reports. These measures are moderately inter‐convertible (Hughes et al., 2010). It is not yet clear which measure is valid to use for assessment of reduction of smoking and health effects (Hatsukami et al., 2006).

Self‐efficacy

We conceptualized this domain as measures assessing self‐efficacy as a facilitator for the mechanisms that lead to improved somatic health. Based on social cognitive theory, judgements of self‐efficacy expectation play major roles in determining whether to perform a specific behaviour in short and long term (Resnick and Jenkins, 2000). Although measures of self‐efficacy are predictors of current physical activity, studies show that interventions directed toward improving self‐efficacy for exercise did improve the exercise rate. However, also measures of self‐efficacy remained unchanged (Lee et al., 2008). No evidence was found on the influence on health related self‐efficacy and mechanism evaluation. Therefore, self‐efficacy cannot be treated as mechanism evaluation.

Adherence to professional guidelines

We conceptualized this domain as measures assessing the amount and/or type of care that was delivered related to the amount and type advised by professional guidelines. The measure adherence to preventive services can be seen as a facilitator to the mechanisms that lead to improved somatic health. Adherence to preventive services is a facilitator for different mechanisms because it supports and controls the start or continuation on an individual level of specific prevention. It is clearly a facilitator of early detection and reducing cardio‐metabolic risk factors, but possibly also for diet, exercise and smoking cessation because advice on life style changes is part of the preventive advice by the guideline. It is unclear what the exact relation is between percentage of increase in preventive services obtained related to changes in health outcome. Furthermore, currently guidelines are available for (preventive) health care for patients with SMI, indicators could, additionally, be derived from these guidelines.

Conclusion

Important elements of HPP are currently not evaluated, based on a comparison of our exploration of expected outcome and mechanism based on theory and the measures used in current practice. Our conceptual frameworks shows that the development of reduced somatic health of patients with SMI goes through multiple interrelated and intertwined pathways. In the current evaluation of outcome of HPP only some of the outcomes of the structural model were assessed. The evaluation of mechanism is only performed for a part of the potential mechanisms described in our theoretical exploration. The evaluation of outcome and mechanism was only partly performed using representative measures for these constructs.

To evaluate outcome of HPP the outcome measures of BMI, blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and HbA1c are representative of the single cardio‐metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, only some extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed as side‐effects. The evaluation was limited to parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia, acathisia was not included. However the responsiveness remains unknown for the measures used for parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia. There are a number of outcome measures available for assessing QoL and the GAF ratings. The elements sexual dysfunction, dental and oral disease, osteoporosis, gastro‐oesophageal reflux and impaired lung function were shown to be important aspects influencing healthy life expectancy in our conceptual framework, but were never evaluated. No suitable instrument is available for general health, however it is a promising construct to assess on an overall scale the amount of morbidity and mortality risks.

Mechanism evaluation was performed for exercise, diet and tobacco smoking which are potentially plausible mechanisms based on our framework. Exercise should ideally be expressed in MET values. For the mechanism of improving diet, currently no instrument is representative. Smoking cessation should be based on biological markers. Added to this, information on intention to quit and dependence should also be collected. Additionally, self‐efficacy and adherence to professional guidelines and self‐efficacy were assessed. Improving self‐efficacy can facilitate different mechanisms, but currently no evidence is present to support the use of this domain to assess the mechanism that is facilitated. Adherence to professional guidelines is linked with health care organization changes and early detection of disease in our framework that can have beneficial effects potentially, but the evidence is not yet present. For the domain adherence to professional guidelines, it is not clear what should be considered as clinically relevant increases.

Strength and limitations

Our study is the first to present an appraisal of the theory and current practice of HPP evaluation. This manuscript emphasizes the need for future research to develop and validate measures for the evaluation of outcome and mechanism of HPP, especially for those domains currently without suitable measures. It was outside the scope of this paper to evaluate measures that were not used in studies on HPP. In the literature, the development from risk factor to somatic disease is descriptively organized either by risk factor or by disease, for the sake of clarity (De Hert et al., 2011a; Robson and Gray, 2007). But, a single disease may be caused by multiple, often interrelated factors that all contribute to the final risk for developing that disease, and a single factor may cause multiple diseases. Our framework clearly depicts that for multiple reasons people with SMI are specifically more vulnerable for cardio‐metabolic diseases due to an additional effect of risk factors in this group. We included only potentially modifiable risk factors, for instance reduced exercise, but for research non‐modifiable risk factors should also be included as confounders. Our conceptual framework should have also included the influences on healthy life expectancy, but this was not possible because information on QoL for these health states in patients with SMI is lacking. Most studies on QoL have only been performed in patients with schizophrenia. Different outcome measures were used to assess the current QoL, and mostly only the influence of a single somatic condition on QoL. A relation has been shown between reduced QoL and cardio‐metabolic risk factors, sexual dysfunction, extra pyramidal symptoms and diabetes (Bebbington et al., 2009; Bobes et al., 2007; Briggs et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2005; Olfson et al., 2005; Strassnig et al., 2003). Although, we have attempted to give a good overview, it is of course only possible to assess the most important causes and diseases in patients with SMI. Moreover, we found no systematic appraisal of evidence on the properties of certain measures.

Meaning of the study and future studies

Our findings on insufficient and lacking measures for HPP evaluation means that the currently available evidence on improving health in patients with SMI is not all based on meaningful evaluations. Parallel to the need to improve somatic health in patients with SMI there is a need for research on methodology and effectiveness of HPP. A priority in research should be given to a cardio metabolic risk assessment for this population. It is striking that currently no grouped risk score is available for an overall assessment of risk for patients with SMI. It is advisable to follow the recommendation by a European expert group to use the relative risk based on smoking, total cholesterol and systolic blood pressure to estimate cardiovascular risk until a specific risk assessment is developed (De Hert et al., 2011a).

The interpretation of QoL values as an effect evaluation of HPP should be interpreted carefully. The valuation of QoL of patients with SMI, and hypothesis on expected changes in QoL after interventions may differ from that in the general population. The sometimes counterintuitive high perception on QoL by patients with SMI also reflects an adaptation to their malicious circumstances. Conversely, interventions that promote positive change, may produce transient decreases in life satisfaction in response to change and the renewed awareness that their lives could be better (Lehman et al., 1993).

Our theoretical exploration can be used for clinical purposes and research. In the clinical setting information from the determinants of health of an individual patient can be related to the possible disease states he/she can develop and which should be prevented. In developing future interventions, the mechanism should be based on theoretical evidence as represented in our theoretical exploration and the evaluation should be performed with meaningful measure. In research it can be used to identify confounders that may influence outcomes.

Deduction

It is theoretically plausible through different mechanisms to improve the somatic health of patients with SMI. Currently, the evaluation of mechanism and outcome is insufficient in HPP. Moreover, not all outcome measures currently in use to assess effect and mechanism are representative for these constructs. There is a great need to improve the somatic health of patients with SMI. Therefore, the development of suitable outcome measures to properly evaluate the characteristics of interventions to improve somatic health deserve highest priority. Our theoretical exploration may offer valuable directions for the selection and development of these outcome measures.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests.

van Hasselt F. M., Krabbe P. F. M., Postma M. J., and Loonen A. J. M. (2015) Evaluation of health promotion programmes in severe mental illness: theory and practice, Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res., 24, pages 83–97. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1456.

References

- Aucott L., Poobalan A., Smith W.C., Avenell A., Jung R., Broom J., Grant A.M. (2004) Weight loss in obese diabetic and non‐diabetic individuals and long‐term diabetes outcomes – a systematic review. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism, 6(2), 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baigent C., Keech A., Kearney P.M., Blackwell L., Buck G., Pollicino C., Kirby A., Sourjina T., Peto R., Collins R., Simes R., Trialists’ Cholesterol Treatment (CTT) Collaborators. (2005) Efficacy and safety of cholesterol‐lowering treatment: prospective meta‐analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet, 366(9493), 1267–1278, DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T.B., Mermelstein R., Collins L.M., Piper M.E., Jorenby D.E., Smith S.S., Christiansen B.A., Schlam T.R., Cook J.W., Fiore M.C. (2011) New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 41(2), 192–207, DOI: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P.E., Angermeyer M., Azorin J., Marwaha S., Marteau F., Toumi M. (2009) Side‐effects of antipsychotic medication and health‐related quality of life in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119(Suppl. 438), 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N.L. (1999) Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107(Suppl 2), 349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman T., Svensson B. (2005) Quality of life in people with severe mental illness. Reliability and validity of the Manchester short assessment of quality of life (MANSA). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59(4), 302–306, DOI: 10.1080/08039480500213733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobes J., Garcia‐Portilla M.P., Bascaran M.T., Saiz P.A. Bousono M. (2007) Quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 9(2), 215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs A., Wild D., Lees M., Reaney M., Dursun S., Parry D., Mukherjee J. (2008) Impact of schizophrenia and schizophrenia treatment‐related adverse events on quality of life: direct utility elicitation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 105, DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W., Bauman A., Chey T., Trost S., Mummery K. (2004) Comparison of surveys used to measure physical activity. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 28(2), 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E.J., Rees K., Ward K., Burke M., Thorogood M. (2007) Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 4(4), CD002128. 10.1002/14651858.CD002128.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J., Chapman N. (2001) Challenges for the prevention of primary and secondary stroke: the importance of lowering blood pressure and total cardiovascular risk. Blood Pressure, 10(5–6), 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. (2012) Smoking and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metabolism Journal, 36(6), 399–403, DOI: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.6.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators (2012) The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta‐analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet, 380(9841), 581–590, DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coons S.J., Rao S., Keininger D.L., Hays R.D. (2000) A comparative review of generic quality‐of‐life instruments. PharmacoEconomics, 17(1), 13–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Dieppe P., Macintyre S., Michie S., Nazareth I., Petticrew M., Medical Research Council Guidance. (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 337, a1655, DOI: 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews M.P., Howes O.D. (2012) Is antipsychotic treatment linked to low bone mineral density and osteoporosis? A review of the evidence and the clinical implications. Human Psychopharmacology, 27(1), 15–23, DOI: 10.1002/hup.1265;10.1002/hup.1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Dekker J.M., Wood D., Kahl K.G., Holt R.I., Moller H.J. (2009) Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 24(6), 412–424, DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Cohen D., Bobes J., Cetkovich‐Bakmas M., Leucht S., Ndetei D.M., Newcomer J.W., Uwakwe R., Asai I., Moller H.J., Gautam S., Detraux J., Correll C.U. (2011a) Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 10(2), 138–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Correll C.U., Bobes J., Cetkovich‐Bakmas M., Cohen D., Asai I., Detraux J., Gautam S., Moller H.J., Ndetei D.M., Newcomer J.W., Uwakwe R., Leucht S. (2011b) Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 10(1), 52–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C.E., Russell J.M., Kuskowski M.A., Caligiuri M.P., Nugent S.M. (2004) Clinical rating scales and instruments: how do they compare in assessing abnormal, involuntary movements? Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(3), 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C.E., Kuskowski M.A., Caligiuri M.P. (2006) Predictors of neuroleptic‐induced dyskinesia and parkinsonism: the influence of measurement methods and definitions. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 26(6), 560–565, DOI: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245559.14284.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGuiseppi C., Atkins D., Woolf S. (1996) Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Alexandria, VA: Virginia International Medical Publishing.

- van Dijk S.B., Takken T., Prinsen E.C., Wittink H. (2012) Different anthropometric adiposity measures and their association with cardiovascular disease risk factors: a meta‐analysis. Netherlands Heart Journal, 20(5), 208–218, DOI: 10.1007/s12471-011-0237-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss B.G., von Esenwein S.A., Compton M.T., Rask K.J., Zhao L. Parker R.M. (2010) A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the primary care access, referral, and evaluation (PCARE) study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(2), 151–159, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson B., Hjalmarson A., Kruse E., Landfeldt B., Westin A. (2001) Effect of smoking reduction and cessation on cardiovascular risk factors. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 3(3), 249–255, DOI: 10.1080/14622200110050510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland A., Eckel R.H. (2011) Does sustained weight loss reverse the metabolic syndrome? Current Hypertension Reports, 13(6), 456–464, DOI: 10.1007/s11906-011-0221-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Aymerich J., Lange P., Benet M., Schnohr P., Anto J.M. (2007) Regular physical activity modifies smoking‐related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population‐based cohort study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 175(5), 458–463, DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200607-896OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharabawi G.M., Bossie C.A., Lasser R.A., Turkoz I., Rodriguez S., Chouinard G. (2005) Abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) and extrapyramidal symptom rating scale (ESRS): cross‐scale comparison in assessing tardive dyskinesia. Schizophrenia Research, 77(2–3), 119–128, DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen N.S., Prescott E. (2011) Benefits of smoking cessation with focus on cardiovascular and respiratory comorbidities. The Clinical Respiratory Journal, 5(4), 187–194, DOI: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2011.00262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen N.S., Prescott E., Osler M. (2005) Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, 294(12), 1505–1510, DOI: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff D.C., Cather C., Evins A.E., Henderson D.C., Freudenreich O., Copeland P.M., Bierer M., Duckworth K., Sacks F.M. (2005) Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66 183–194, quiz 147, 273–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B., Davies C., Scott D. (2012) Health behaviour interventions to improve physical health in individuals diagnosed with a mental illness: a systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(3), 236–247, DOI: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00816.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hasselt F., Krabbe P., van Ittersum D., Postma M., Loonen A. (2013) Evaluating interventions to improve somatic health in severe mental illness: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 128, 251–260, DOI: 10.1111/acps.12096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D.K., Benowitz N.L., Rennard S.I., Oncken C., Hecht S.S. (2006) Biomarkers to assess the utility of potential reduced exposure tobacco products. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 8(2), 169–191, DOI: 10.1080/14622200600576628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt J. (2007) Critical evaluation of the use of research tools in evaluating quality of life for people with schizophrenia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(1), 2–14, DOI: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J.R., Carpenter M.J., Naud S. (2010) Do point prevalence and prolonged abstinence measures produce similar results in smoking cessation studies? A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 12(7), 756–762, DOI: 10.1093/ntr/ntq078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen Y.R. (2009) Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(4), 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram M.B., Hosalli P., Stroup S. (2006) Risperidone versus olanzapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 2(2), CD005237, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005237.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao Y.C., Liu Y.P., Chou M.K., Cheng T.H. (2011) Subjective quality of life in patients with chronic schizophrenia: relationships between psychosocial and clinical characteristics. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(2), 171–180, DOI: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesaniemi Y.K., Danforth E. Jr, Jensen M.D., Kopelman P.G., Lefebvre P., Reeder B.A. (2001) Dose‐response issues concerning physical activity and health: an evidence‐based symposium. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(6 Suppl), S351–S358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S., Saito K., Tanaka S., Maki M., Yachi Y., Asumi M., Sugawara A., Totsuka K., Shimano H., Ohashi Y., Yamada N., Sone H. (2009) Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta‐analysis. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(19), 2024–2035, DOI: 10.1001/jama.2009.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshizaka M., Green J.B., Alexander J.H. (2012) Glycemic management in diabetes and the associated cardiovascular risk. Circulation Journal: Official Journal of the Japanese Circulation Society, 76(7), 1572–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom M.H., van Weert C.H.M. (2008) Meedoen en gelukkig zijn, een verkennend onderzoek naar de participatie van mensen met psychiatrische problemen of een verstandelijke beperking. Den Haag: SCP. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte M.C., Perreault S., Jouini G., Shea B.J., Lalonde L. (2011) Effectiveness of interventions to improve the detection and treatment of osteoporosis in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Osteoporosis International: A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA, 22(11), 2743–2768, DOI: 10.1007/s00198-011-1557-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Wald N., Morris J. (2003) Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 7(31), 1–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear S.A., Brozic A., Myers J.N., Ignaszewski A. (1999) Exercise stress testing. An overview of current guidelines. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 27(5), 285–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.L., Arthur A., Avis M. (2008) Using self‐efficacy theory to develop interventions that help older people overcome psychological barriers to physical activity: a discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(11), 1690–1699, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.C., Sui X., Artero E.G., Lee I.M., Church T.S., McAuley P.A., Stanford F.C., Kohl H.W. 3rd, Blair S.N. (2011) Long‐term effects of changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index on all‐cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men: the aerobics center longitudinal study. Circulation, 124(23), 2483–2490. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A.F., Postrado L.T., Rachuba L.T. (1993) Convergent validation of quality of life assessments for persons with severe mental illnesses. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 2(5), 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loonen A.J., van Praag H.M. (2007) Measuring movement disorders in antipsychotic drug trials: the need to define a new standard. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(5), 423–430, DOI: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31814f1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik P. (2007) Sexual dysfunction in schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(2), 138–142, DOI: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f6c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas‐Exposito L., Amador‐Campos J.A., Gomez‐Benito J., Lalucat‐Jo L., Research Group on Severe Mental Disorder . (2011) The World Health Organization quality of life scale brief version: a validation study in patients with schizophrenia. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 20(7), 1079–1089, DOI: 10.1007/s11136-011-9847-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J.M., Nasrallah H.A., McEvoy J.P., Goff D.C., Davis S.M., Chakos M., Patel J.K., Keefe R.S., Stroup T.S. Lieberman J.A. (2005) The clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial: clinical comparison of subgroups with and without the metabolic syndrome. Schizophrenia Research, 80(1), 9–18, DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mookhoek E.J., Meijs V.M., Loonen A.J., Leufkens H.G. (2005) Dyspepsia in chronic psychiatric patients. Pharmacopsychiatry, 38(3), 125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossberg K.A., Fortini E. (2012) Responsiveness and validity of the six‐minute walk test in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Physical Therapy, 92(5), 726–733, DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20110157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J., Kaykha A., George S., Abella J., Zaheer N., Lear S., Yamazaki T., Froelicher V. (2004) Fitness versus physical activity patterns in predicting mortality in men. The American Journal of Medicine, 117(12), 912–918, DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . (2011) NICE Clinical Guideline 127 – Hypertension. London: NICE. [Google Scholar]

- Norholm V., Bech P. (2007) Quality of life assessment in schizophrenia: applicability of the Lehman quality of life questionnaire (TL‐30). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61(6), 438–442, DOI: 10.1080/08039480701773154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien C., Gardner‐Sood P., Corlett S.K., Ismail K., Smith S., Atakan Z., Greenwood K., Joseph C., Gaughran F. (2013) Provision of health promotion programmes to people with serious mental illness: a mapping exercise of four south London boroughs. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(2), 121–127, DOI: 10.1111/jpm.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M., Uttaro T., Carson W.H. Tafesse E. (2005) Male sexual dysfunction and quality of life in schizophrenia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(3), 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen L.R., Mortensen E.L., Bech P. (2004) The SCL‐90 and SCL‐90R versions validated by item response models in a Danish community sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(3), 225–229, DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Chiros C.E., Gutierrez P.M., Kopper B.A., Barrios F.X. (2001) Factor structure and psychometric properties of the brief mizes anorectic cognitions questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(6), 785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øvretveit J. (1998) Evaluating Health Interventions . Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Poppel M.N., Chinapaw M.J., Mokkink L.B., van Mechelen W., Terwee C.B. (2010) Physical activity questionnaires for adults: a systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 40(7), 565–600, DOI: 10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Simmons R.K., Hennings S.H., Wareham N.J., Griffin S.J. (2012) Effect of screening for type 2 diabetes on population‐level self‐rated health outcomes and measures of cardiovascular risk: 13‐year follow‐up of the Ely cohort. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association, 29(7), 886–892, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03570.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven G.M. (2011) The metabolic syndrome: time to get off the merry‐go‐round? Journal of Internal Medicine, 269(2), 127–136, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves S., Zwarenstein M., Goldman J., Barr H., Freeth D., Hammick M., Koppel I. (2008) Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 1(1), CD002213, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B., Jenkins L.S. (2000) Testing the reliability and validity of the self‐efficacy for exercise scale. Nursing Research, 49(3), 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson D., Gray R. (2007) Serious mental illness and physical health problems: a discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe L., Strong C., Whiteside C., Neil A., Mant D. (1994) Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Family Practice, 11(4), 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadock B.J., Sadock V.A., Kaplan H.I. (2009) Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychaitry . Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkings. [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Chant D., McGrath J. (2007) A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(10), 1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K., Gennat H., O'Rourke P., Del Mar C. (2006) Exercise for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 4(4), CD003817, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003817.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skevington S.M., Lotfy M., O'Connell K.A., WHOQOL Group (2004) The World Health Organization's WHOQOL‐BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 13(2), 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Allwright S., O'Dowd T. (2007) Effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 3(3), CD004910, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004910.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Soubhi H., Fortin M., Hudon C., O'Dowd T. (2012) Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 4, CD006560, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder M.B., van Dam R.M., Visser M., Seidell J.C. (2006) What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them? International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(1), 83–92, DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyi253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg P., Tungstrom S., Armelius B.A. (2005) Reliability of global assessment of functioning ratings made by clinical psychiatric staff. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 56(4), 434–438, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.4.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassnig M., Brar J.S., Ganguli R. (2003) Body mass index and quality of life in community‐dwelling patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 62(1–2), 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranter S., Irvine F., Collins E. (2012) Innovations aimed at improving the physical health of the seriously mentally ill: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(9–10), 1199–1214, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor‐Locke C., Williams J.E., Reis J.P., Pluto D. (2002) Utility of pedometers for assessing physical activity: convergent validity. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 32(12), 795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D.E., Nicol C.W., Bredin S.S. (2006a) Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal [Journal De l'Association Medicale Canadienne], 174(6), 801–809, DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.051351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D.E., Nicol C.W., Bredin S.S. (2006b) Prescribing exercise as preventive therapy. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal [Journal De l'Association Medicale Canadienne], 174(7), 961–974, DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.1040750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J.E. Jr, Sherbourne C.D. (1992) The MOS 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnakulasuriya S., Dietrich T., Bornstein M.M., Casals Peidro E., Preshaw P.M., Walter C., Wennstrom J.L., Bergstrom J. (2010) Oral health risks of tobacco use and effects of cessation. International Dental Journal, 60(1), 7–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh N., Scotland G., McNamee P., Gillett M., Brennan A., Goyder E., Williams R., John A. (2007) Screening for type 2 diabetes: literature review and economic modelling. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 11(17), iii–iv, ix–xi, 1–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D.D. (1968) Critical analysis of the disability in Parkinson's disease. Modern Treatment, 5(2), 257–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildgust H.J., Beary M. (2010) Are there modifiable risk factors which will reduce the excess mortality in schizophrenia? Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 24(4 Suppl), 37–50, DOI: 10.1177/1359786810384639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf‐May K., Ferrett D. (2008) Metabolic equivalents during the 10‐m shuttle walking test for post‐myocardial infarction patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(1), 36–41; discussion 41, DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.034116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Sin D.D. (2011) Improved patient outcome with smoking cessation: when is it too late? International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 6, 259–267, DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S10771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwarenstein M., Goldman J., Reeves S. (2009) Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 3(3), CD000072, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]