Abstract

Disparities in the prevalence of mental illness are widely reported for people from ethnic minorities. Unlike the United States, there is no legislation for clinical research in the UK to mandate the inclusion of ethnic minorities and they are underrepresented in European trials compared with those conducted in the United States. This restricts generalization of research findings.

This systematic review of the barriers to the recruitment of ethnic minority participants into psychiatric research is based on a comprehensive literature search. Nine included papers explore such barriers based on the authors’ and participants’ experiences of research. These barriers are mainly categorized as: participant related, practical issues, family/community related, health service related and research process issues.

This review provides a compilation of important barriers to recruitment which can facilitate future research. The barriers that were identified are not all unique to participants from ethnic minorities, although the way in which they manifest themselves is often distinct in minority groups. It is important that these barriers are considered when designing research design so that solutions to overcome such obstacles can be incorporated in research protocols from the start and appropriate resources allocated. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: systematic review, ethnic minorities, mental health research, recruitment, barriers

Background

Most developed countries have substantial ethnic minorities (Healthcare Commission, 2005; US Census Bureau, 2009). Ethnic minorities have comparatively higher rates of: depression (Miranda et al., 2003; Gater et al., 2009), schizophrenia (Fearon et al., 2006; Bresnahan et al., 2007), suicide (Hovey, 2000; Bhui et al., 2007) and self‐harm (Cooper et al., 2006), with large variation in rates between ethnic minorities and countries of residence. Yet, ethnic minorities are less likely to take part in mental health research (Miranda, 1996; Hussain‐Gambles et al., 2004). This lack of participation inhibits service development for ethnic minorities.

In the United States, where National Institute of Health (NIH) guidelines mandate the inclusion of ethnic minorities in clinical trials, minority participation is better than in Europe (Sheikh et al., 2004). In the absence of a similar policy in the UK, it is important to consider other ways of improving participation (Waheed et al., 2003).

There are two approaches to improve minorities’ participation in clinical research. The first approach, is to ensure that ethnic minorities are proportionately represented in clinical studies. The second, is to conduct studies specifically in ethnic minority populations. The first approach is suitable when the research question is relevant to the general population, such as whether a treatment works or not. The second is appropriate when the research question specifically focuses on ethnic minorities, such as, how far a particular approach improves access to care.

There are no published systematic or non‐systematic reviews of ethnic minorities’ recruitment into mental health research. Whilst observations made in health research may be extrapolated to mental health, there may be barriers unique to mental health research.

The aims of the review are to describe the barriers to recruiting ethnic minorities into mental health research. Although there is existing research in other disease categories (Yancey et al., 2006), looking into these barriers, we need to explore this specifically in relation to mental health; as the nature of the mental illness and needs of the patients are different from physical health categories.

Methodology

Eligible studies described the researchers’ experiences of methods to increase recruitment of ethnic minorities to any type of mental health research. We included: (a) descriptions of experiences based on specific studies; and (b) descriptions of experiences based on an overview of several studies.

The search strategy was devised by an experienced researcher in ethnic minority research (WW) and a medical librarian examining reviews (Yancey et al., 2006; Ford et al., 2008) in other specialities. Search terms represented three domains: (1) participation or recruit or retain; (2) ethnic minorities (exploded) or culture; (3) research or trial and the key words within three domains were combined using “OR” and “AND”. We searched: Medline (1950), Embase (1980), PsycINFO (1806) and Cinahl (1981) up to 16 November 2011 with no language restrictions and imported results into Reference Manager 12. All titles and abstracts were available in English.

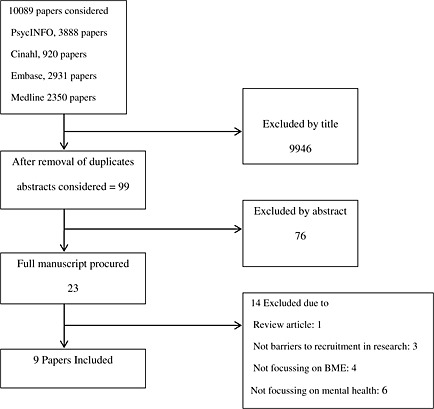

A data extraction form was designed a priori and pilot tested. Information was extracted on: study authors, publication year, and setting and design; specifically distinguishing between the overall design of the study and the means in which barriers to participation data was obtained. Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (GB and AW). During extraction whenever a new barrier was identified, it was added to the extraction form in an evolving process. Discrepancies were removed by consensus in presence of WW. Later these barriers were grouped into broad themes. These groupings are not mutually exclusive, which makes some repetition within the review necessary (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart.

Results

The initial search identified 10,089 papers. Of these 9946 were excluded by reading the title and a further 76 papers by reading the abstract. After removing duplicates 23 papers were eligible for inclusion. Following full text consideration, a further 14 papers were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were: policy review article (1), not documenting barriers to recruitment (3), not focussing on ethnic minorities (4) and not specifically focussing on mental health (6). All nine included papers were in English and hand search of their references did not find any additional papers.

All nine included papers were from the United States, qualitatively describing researchers’ narratives, none of which reported on any quantitative barrier related data. A summary of these papers is provided in Table 1. The barriers to recruitment identified by the papers are summarized in Table 2, under participant, practical, family/community issues and research process issues.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Title | Setting | Ethnic group | Diagnostic category | Description | Design | Source of data reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miranda et al. (1996) | San Francisco, USA Hospital | Latino | Depression | Experiences from 4 different trials. | 2 preventative and 2 treatment studies. | Authors’ own experiences |

| Thompson & Neighbors (1996) | Detroit, Michigan, USA Hospital | African American | Schizophrenia or mood disorder | A study on the influence of ethnicity on diagnosis in psychiatric inpatients. | Cross sectional study | Direct participant interview & authors experiences |

| Le et al. (2008) | Washington DC, USA and Mexico City, Mexico Community health care | Latino | Postpartum depression | Recruitment data from two RCTs of preventative interventions. | Cross sectional comparative study | Authors’ own experiences |

| Arean et al. (2003) | San Francisco Bay, USA Community clinic | African American | Depression or anxiety | Traditional methods of recruitment versus consumer‐centred approach | Comparative observational studies | Authors’ own experiences |

| Meinert et al. (2003) | Cleveland, Ohio, USA Community | African American | Depression | Mental health conference based on NIH guidelines on the inclusion of minorities | Intervention study | Participants views of barriers |

| Gallagher‐Thompson et al. (2004) | Community, San Francisco Bay USA | Latino | Dementia | Comparison of three recruitment strategies | Cross‐sectional nested study | Authors’ own observations |

| Chen et al. (2005) | Manhattan, New York City, USA Neighbourhood health centre | Asian American | Depression | Description of building research programmes in the community. | Review article | Authors’ own experiences |

| Aliyu et al. (2006) | South Eastern USA Multiple academic medical centres | African American | Schizophrenia & Schizoaffective disorder | Maximizing recruitment, retention & forging community ties. | Description of a protocol | Authors’ own experiences. |

| Loue & Sajatovic (2008) | San Diego County, California and North East Ohio, USA | Latino | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression | Overview of author's own experience from several studies | Review article | Authors’ own experiences |

Table 2.

Table to show frequency of barriers across studies

| Barrier | Miranda (1996) | Thompson & Neighbors (1996) | Le et al. (2008) | Arean et al. (2003) | Meinert et al. (2003) | Gallagher‐Thompson et al. (2004) | Chen et al. (2005) | Aliyu et al. (2006) | Loue & Sajatovic (2008) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant related barriers | Explanatory models of illness | X | ||||||||

| Help‐seeking/negative attitude to psychotherapy | X | X | X | |||||||

| Language | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Religious beliefs | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Trust | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Stigma | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Gender | X | X | X | |||||||

| Psychopathology/substance misusea | X | |||||||||

| Fear of being reported to immigration | X | X | ||||||||

| Practical issues | Lack of child care | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Transport provision | X | X | X | |||||||

| Financial constraints | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Culturally inappropriate incentive | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Medical insurancea | X | X | ||||||||

| Lack of time | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Location of interview | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Employment status | X | |||||||||

| Family/community | Husbands’ influence | X | X | |||||||

| Family perspectives | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Stigma for family | X | X | ||||||||

| Health service related | Underutilization of mental health servicesa | X | ||||||||

| Language of professional/intervention | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Lack of communication and cultural awareness between staff and participants | X | X | X | |||||||

| Staff personal attributes | X | X | ||||||||

| Research process | Limited willingness and enthusiasm of researchers | X | X | X | ||||||

| Understanding the need for ethnic participation | X | |||||||||

| Paucity of resources available | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Appropriateness of assessment tools | X | |||||||||

| Non‐availability of translated materials | X | X | X | |||||||

| Lack of culturally competent staff | X | X | X | |||||||

| Lack of culturally matched staff | X | X | X | |||||||

| Under representation of ethnic minorities at recruitment sites | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Understanding of consent process | X | X |

Indicates those barriers that are not modifiable within the scope of the study.

Participant related barriers

Explanatory model of illness

In a study of depression, authors reported that a lack of knowledge could result in people over‐generalizing or over‐simplifying symptoms and denial to be a typical response, with patients not considering depressed moods as a medical condition requiring treatment (Chen et al., 2005).

Help seeking/negative attitudes to psychotherapy

Three papers cited help seeking preferences and attitudes towards psychotherapy as potential barriers. Recruitment of African Americans in Detroit was hindered by negative attitudes toward psychotherapy. The authors found African Americans with emotional problems preferring alternatives to mental health services or not seeking help at all (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). Another study, describes African Americans placing emphasis on the role of prayer, spirituality and referred to spiritual support organizations “the unique role of mutual support available within Sister circles in local communities” (Meinert et al., 2003). Both papers report that people in their sample, would be unlikely to seek professional help and people felt that receiving psychotherapy meant seeking assistance outside the family. Another included paper (Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004) mentioned “help‐seeking” being a barrier, although did not elaborate on this comment. It was concluded that the earlier mentioned problems “often results in small pools of African Americans from which to sample” (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996).

Language

Five papers covering Latinos, African Americans and Asian Americans highlighted language related barriers to recruitment. The authors of one paper describing multisite recruitment of Latinos commented, “the issue of communication between the provider/care network staff and the patient with serious mental illness was seen as a potentially overwhelming barrier in many clinical settings” and participants were often monolingual in Spanish or preferred to speak in Spanish (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). A paper describing recruiting from low income Latinos (Miranda et al., 1996), highlighted non‐availability of culturally adapted questionnaires as a barrier. A further study, in Asian Americans commented that, “Asian American immigrants, especially elders, have also relatively lower literacy levels” (Chen et al., 2005).

Highlighting the importance of being culturally sensitive within target language, authors found that at times “the required language and phrases stipulated by institutional review board, when translated into Spanish, may contain a number of specific words and phrases that were alarming to our target population” (Le et al., 2008). Another paper concluded that by listening to the views of African‐American women they had “acquired a greater sensitivity to the language and common expressions of African‐Americans”. The fifth paper mentioned language as a barrier to recruitment but did not elaborate further (Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004).

Religious beliefs

Four papers identified religion as a barrier to recruitment. The first focusing on recruiting Latinos reported that “many Latinos are Catholic and, whilst authors recognised that alternative treatments and folk beliefs about psychiatric symptoms are unlikely to interfere with their participation in research, these issues may affect diagnoses and exclusionary criteria” proposing that some Latinos present with beliefs that can appear psychotic out of context, despite being culturally appropriate (Miranda et al., 1996). Other papers found that religion can lead to help seeking from alternate sources. Some African Americans, who have faith in prayer and spirituality may seek help from religious leaders (Sister circles in local communities) rather than health professionals (Meinert et al., 2003). Further to this the authors reported that awareness of religious holidays must be incorporated into recruitment efforts (Arean et al., 2003), and that competing obligations such as attendance at church functions can affect potential participants’ willingness to engage in research (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Trust

Five papers identified mistrust as a factor that inhibited recruitment. Three papers (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996; Arean et al., 2003; Meinert et al., 2003), covered mistrust in African Americans, linked to a legacy of unethical research conducted by White researchers, particularly Tuskegee Scandal (Blacks were not offered efficacious syphilis treatment). It was stated that “Understandably, African Americans tend to distrust research in general and research conducted by whites in particular” (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996) and “some African Americans believe that their race are used as guinea pigs in medical research and inevitably, willingness to participate in clinical trials involves a strong element of trust” (Meinert et al., 2003).

A different element of mistrust as a barrier stems from participants’ suspicion about services (Meinert et al., 2003; Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004). African‐American women voiced suspicion about mental health services. Authors highlighted women's fear of physicians (especially psychiatrists) “the view that psychiatrists are like policemen suggests that African‐American encounters with them are often followed by involuntary hospitalization” and “participants also identified their suspicion of the perceived profit motive of pharmaceutical companies” (Meinert et al., 2003).

Another paper referred to the same issue of trusting professionals, stating that “traditionally Latinos have tended to be wary of professionals who they do not know” (Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004).

A paper about Asian Americans described how they viewed the consent process and legal documents with suspicion (Chen et al., 2005).

Stigma

Seven papers identified stigma as a barrier, in the sense that stigma relating to mental health being a greater problem in some ethnic minorities compared to Whites.

Three papers reported that the stigma attached to mental illness was a particular problem in African Americans (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). Authors quoted a women saying “crazy, scary, weakness, helpless, hopeless, irresponsibility, and stigma” in association with mental health research and “one participant noted that she was taught to keep personal issues in the family and deal with them by keeping a stiff upper lip” (Meinert et al., 2003). Another paper about recruitment in African Americans commented that “the stigma associated with psychiatric illnesses might be magnified and misused in the context of research involving members of a minority group” (Aliyu et al., 2006).

Authors noted in Latinos that “fear of being stigmatised as a result of study participation or being recognised as mentally ill” (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). The fear of being labelled mentally ill was particularly pronounced in Asian American communities, despite their limited exposure to research (Chen et al., 2005). Authors report that, “Whereas many older white patients may be concerned with what others will think of them if a mental health diagnosis is uncovered, many older minorities may be more concerned with the impact a psychiatric diagnosis will have on their family's reputation” (Arean et al., 2003).

Gallagher‐Thompson et al. (2004) reported on stigma as a barrier, although did not elaborate on how stigma interferes with the recruitment process.

Gender

Three papers, about Latino communities, mentioned gender as a barrier to recruitment. One reported that females were unable to participate due to their husbands’ disapproval of the research and recommended that the “man of the family” be included in discussions before the wife was recruited (Miranda et al., 1996). Another study reported that relationship issues, such as partner violence were a barrier to recruitment in their study (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

A woman's traditional role in Latino culture was discussed by the authors in context of research “a woman's traditional role as a good housewife and mother‐prominent among the less educated suggests that participating in competing activities may seem too selfish”. Authors found that women were often uncomfortable about refusing to participate, and so provided passive consent to appointments. This may be due to the woman wanting to respond in a socially desirable manner and not to disappoint research staff. Inevitably this led to subsequent withdrawals or non‐engagement (Le et al., 2008).

Psychopathology/substance misuse

A paper describing experiences with South Americans, found psychopathology and/or use of substances, a recruitment barrier (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). Three Puerto Rican and two Mexican women were lost to follow‐up because of psychopathology or substance use. Increased drug use led to unreliability in attending appointments and raised concerns about their capacity to consent.

Fear of being reported to immigration

Two papers commented about illegal immigrants expressed fear of being reported to immigration in case they participated in research. Authors reported that phrases in the consent form raised concerns about possible deportation (Le et al., 2008). Another paper documented similar deportation fears in illegal Mexican migrants (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Practical issues

Lack of child care

Four papers mentioned child care as a recruitment barrier. One paper found Latino community reporting more practical barriers like child care, than Whites (Miranda et al., 1996). Another paper found that child‐care issues were frequently cited for non‐participation and inability to attend clinics by Latino women (Le et al., 2008). A paper about depressed African‐American women found child care as a barrier to access treatment (Meinert et al., 2003). It was suggested that Asian Americans elders may be unable to enter research studies as they may have child‐care responsibilities. Authors raised the possibility that child‐care issues may be an effect of poverty rather than ethnicity as such (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Transport provision

Three papers referred to lack of transport. Latino mothers were unable to attend research site because of transportation limitations (Miranda et al., 1996), Latinos in San Francisco Bay reported that difficulties with transportation deterred participation (Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004). While suggesting that this barrier may be caused by poverty, rather than ethnicity as such authors referred to the “financial considerations that impacted the individuals’ ability to pay for transportation costs” (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Financial constraints

Five papers commented on participants’ financial position as a barrier. People of low socio‐economic status report more barriers to obtaining mental health care, compare to Whites and higher income individuals (Miranda et al., 1996). African‐American patients from low‐income areas expressed more reluctance to participate in research (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). Low‐income immigrants may hesitate to incur the additional health‐care expense and believe that participation in a trial will incur costs (Chen et al., 2005; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). Authors suggested that ethnic minority elders may have limited resources and be deterred by financial constrains (Arean et al., 2003).

Culturally inappropriate incentives

It was common for studies to offer incentives to recruitment (Miranda et al., 1996; Thompson and Neighbors, 1996; Arean et al., 2003; Meinert et al., 2003) However, two studies pointed out how certain incentives could have a negative impact on recruitment. Researchers found that some people did not want to be pressured by the extra monetary obligation and others felt embarrassed thinking that they should be paying for services, not the other way round (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). Some Asian elders did not feel comfortable accepting monetary incentives, and felt that their information was being sold as part of a cheap material exchange (Chen et al., 2005).

Medical insurance

Two papers identified lack of medical insurance as a barrier to recruitment (Miranda et al., 1996; Meinert et al., 2003); reporting that some depressed African‐American women did not have access to treatment because of inadequate health insurance.

Lack of time

Five papers reported lack of time as a barrier. Authors reported that the most common reason for Latinos non‐participation was “lack of time/too busy” (Le et al., 2008). Lack of time was a factor that was cited across age groups, but was particularly common in adults from ethnic minorities who were often experiencing multiple psychosocial stressors and limited resources (Miranda et al., 1996; Arean et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Location of interview

Five papers referred to the location of the research interview/intervention as a barrier to recruitment (Miranda et al., 1996; Arean et al., 2003; Meinert et al., 2003; Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). One of the papers commented “paranoia, could interfere with individuals’ willingness and ability to present at a less familiar location and result in their withdrawal from the study” and ethnic participants may be reluctant to attend mental health facilities, fearing to be identified by other members of their community (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Employment status

A paper cited conflict with employment requirements as the most common reason for Latinas non‐participation (Le et al., 2008)

Family/community related

Husbands’ influence

Two papers on Latino populations commented on prohibitions by husbands or partners as a barrier to recruitment of women from ethnic minorities (Miranda et al., 1996; Le et al., 2008). Some women may accept a submissive role and comply with their partners’ prohibitions against their active participation in the interventions (Le et al., 2008).

Family perspectives

Four papers, across different samples, referred to the family as a barrier to recruitment. Two studies (Miranda et al., 1996; Le et al., 2008) involving Latinos, recorded how strong traditional family values, could make recruitment difficult stating that “adherence to traditional gender roles” and “respect towards elders may be unique facilitators or barriers for recruiting Latina participants into intervention research”. However, this paper also suggested that families can assist with the recruitment process as well as hinder it. Another paper reported on how family commitments restrict participants’ recruitment (Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). African Americans reported that people were deterred from seeking treatment because it represented a failure to keep problems in the family. The authors reported that participants “felt that receiving psychotherapy meant seeking assistance outside the family” (Meinert et al., 2003).

Stigma for the family

Two papers referred to stigma in the family context as a barrier to recruitment. Authors reported that some elder African Americans were more concerned with the impact a psychiatric diagnosis would have on their family's reputation than on themselves (Arean et al., 2003). Another paper about Asian Americans reported “a difference between stigmas associated with different illnesses was observed, for example depression is generally less stigmatizing than psychosis. The less stigma that is linked to a project, the more support a community is likely to give” (Chen et al., 2005). This study found that most Asian community leaders appeared to be understanding and sympathetic regarding the mental health aspects of research projects, which seems to contradict what is reported earlier. The authors reported that the leaders “all agreed with the need for services but also believed that the stigma would potentially obstruct the project”.

Health service related

Under‐utilization of mental health services

A paper on recruitment of Latinos, suggested that under recruitment was due to low levels of engagement with mental health services. Since the study recruited from existing mental health service users, it was almost inevitable that ethnic minorities would be under‐represented as they underutilized these services (Miranda et al., 1996).

Language of professional/intervention

Four papers made reference to the importance of the language of the intervention and researcher, stating about Latinos “providing services in Spanish is essential for recruiting monolingual Spanish‐speaking Latinos” (Miranda et al., 1996). Authors also reported that, “bilingual‐bicultural staff were able to maintain Latino patients in treatment at the same rate as our non‐Latino sample” and all treatments were conducted in Spanish. The other three papers (Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004; Le et al., 2008; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008) documented the importance of having bilingual and bicultural staff to assist with recruitment, with another paper (Le et al., 2008) stating that “the use of bicultural research staff and clinic staff increased the number of screening interviews conducted”. The paper by Gallagher‐Thompson et al. (2004) about recruitment of Latinos describes involvement of staff in facilitating the recruitment procedures.

Lack of communication and cultural awareness between staff and participants

Three papers referred to the importance of communication between research staff and participants. The need to show respect toward male figures and older adults in general, were important aspects of Latino culture that needed to be considered (Miranda et al., 1996; Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004; Le et al., 2008). Latinos are expected to be warm and personal in their interactions with others, a concept called simpatía (Miranda et al., 1996; Gallagher‐Thompson et al., 2004; Le et al., 2008). Important aspects of this personal approach include the use of formal language (Usted, Señor, Señor, etc.) and formal greetings in professional relationships (Miranda et al., 1996). The papers highlight the importance of being culturally aware when approaching participants and their families.

Staff personal attributes

Two papers commented on the importance of personal attributes in recruitment of ethnic groups (Miranda et al., 1996; Le et al., 2008). Latinos responded well to the Simpatía and Personalísmo of others and as per Miranda et al. (1996), “traditional approaches to recruiting participants into treatment outcome studies may be perceived as both too informal and too cold for many Latinos”. This paper surmised that “the success in retaining the subjects is attributed to a careful individualised approach” and the researcher's ability to remember details of the participants’ family situations and develop personal rapport was highlighted. Furthermore researcher need to “warm, friendly and interested in their [participants’] wellbeing”.

Research process

Limited willingness and enthusiasm of researchers

Three papers, across multiple samples, reported lack of enthusiasm from researchers as a barrier to recruitment. Detailing the recruitment of African‐American participants (Arean et al., 2003), stated “failing to understand the specific culture of the target population, they had inadvertently distanced themselves from the community and the gate‐keepers, doing little to overcome attitudes about research and mental health”. Belatedly, the authors recognized that their research strategy, to its detriment, had been “minimally informed by the culture of the community we were working with”.

However, while recruiting Latinos, Gallagher‐Thompson et al. (2004) reported that “professional referrals were the most successful recruitment method, far more so than media efforts and non‐professional referrals”. The enthusiasm of researchers to develop strong working relationships with professionals in the recruitment area was vital to successful recruitment. While recruiting Asian Americans, Chen et al. (2005) expressed the need for “research staff to stress uniquely potential impact of certain elements of the study on both the medical staff and the patients”. Within this paper the authors stressed the need for researchers to “emphasise the cultural competence elements of the study”.

Whilst enthusiasm to promote the research is highly important, the authors referred to the importance of considering how the service providers’ will is conveyed practically in action, stating, “overemphasising the academic needs of research could be interpreted as a sign of self‐serving intent that is irrelevant to a community's need” (Chen et al., 2005). The literature would suggest that this barrier is particularly important to overcome particularly where there is an ethnic mismatch between the research staff and the participants.

Understanding the need for ethnic participation

A paper focussing on African‐American participants, commented that service providers underestimating the need to include ethnic groups in psychiatric research was a huge barrier to recruitment (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). The authors stated “African American patients are frequently considered to be a research risk because they are less likely to be found or to participate for the duration of the study” and “African American men are sometimes viewed as violent and threatening. These factors undoubtedly contribute to the fact that many researchers may be reluctant to conduct research focused specifically on African Americans”

Paucity of resources available

Seven out of the nine included papers referred to study resources as barriers to recruitment. Amongst Latinos, lower participation rates may be due to not providing culturally and linguistically appropriate staff (Miranda et al., 1996). Other authors emphasized the importance of having culturally appropriate interviews and scales with accurate translations (Chen et al., 2005).

Focusing on the recruitment of African Americans, it was concluded that “sufficient time and money should be allocated during the research planning stage to develop culturally sensitive strategies that incorporate the reactions of African American patients into the preparation and implementation process” (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). Papers described the importance of spending time and resources prior to recruitment on developing partnerships between research staff and gatekeepers to the community (Arean et al., 2003; Aliyu et al., 2006; Le et al., 2008; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Appropriateness of assessment tools

It was highlighted that assessment tools used could act as a barrier to recruitment (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). The potential participants were multi‐ethnic but predominantly African Americans with little knowledge of research and poor literacy. Limited availability of assessment tools in their native language was observed.

Non‐availability of translated materials

Three papers commented on study materials acting as a barrier to recruitment. For Latinos, “many commonly used instruments in psychotherapy research have not been translated into Spanish or validated on Spanish‐speaking populations” (Miranda et al., 1996). In written materials, there is a risk that some directly translated words may be perceived as stigmatizing or simply confusing (Le et al., 2008). Other issues may arise when character names and descriptions used, therefore materials should be culturally appropriate, beyond simple language translations (Chen et al., 2005).

Lack of culturally competent staff

Three papers raised the importance of culturally competent staff in recruitment (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996; Arean et al., 2003; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008). They employed staff experienced in working with ethnic minorities. The staff were not ethnically matched but rather had the skills, experience and cultural awareness to engage the target population.

Lack of culturally matched staff

Three papers referred to ethnically matching researchers and participants. Perhaps surprisingly one study, recruiting African‐American participants, found that matching had no noticeable influence on refusal rates (Thompson and Neighbors, 1996). This was supported by another study in African Americans (Arean et al., 2003) reporting that “experience was more important than ethnic matching” when recruiting. By “experience” the authors meant previous experience with similar ethnic groups. Amongst Asian Americans it was suggested that the critical factor was not ethnic matching per se, but the researcher's cultural competence in building trust with participants (Chen et al., 2005).

Under representation of ethnic minorities at recruitment sites

Six papers considered low availability of ethnic participants at the recruitment sites as low numbers of ethnic residents in that particular area can limit the pool of potential participants (Miranda et al., 1996; Thompson and Neighbors, 1996; Meinert et al., 2003; Aliyu et al., 2006; Le et al., 2008; Loue and Sajatovic, 2008).

Understanding of consent process

Two papers referred to obtaining consent as a barrier to recruitment. Focusing on Asian Americans authors found that “Asian Americans are not accustomed to the process of giving written informed consent for treatment, and they are relatively inexperienced in participating in research trials, which they may view with suspicion”. In addition consent forms may lead to immigrant adults refusing to participate in a study because of their suspicion of any legal documents (Chen et al., 2005). The second paper described problems arising in recruiting a Latina sample where great care had to be taken to ensure they fully understood the intent and contents of the research consent forms (Le et al., 2008). Explaining study procedures can be difficult as it is hard to frame randomization in a manner that is understandable and acceptable to potential participants (Chen et al., 2005).

Discussion

This review is the first systematic attempt to identify barriers that hinder recruitment of ethnic minorities to mental health research. The main benefit is that we now have a compilation of important barriers to recruitment. Researchers, once aware of these barriers can plan ahead and incorporate design modifications at protocol writing stage to facilitate eventual ethnic minorities’ recruitment.

The results tell us that even before the actual initiation of research study and the recruitment process, there is a critical barrier leading to under recruitment. Ethnic minorities in question underutilize the health services where the research is conducted thus reducing their chances of participation.

Subsequently once a research study is rolled out there is interplay of various barriers with a large overlap. Many of these barriers are not specific to ethnic minorities and are clearly encountered when working with majority populations that are often Caucasians and of low socio‐economic status in particular. For example child care may be a barrier for both Caucasian and ethnic minority participants, although the options available to address this issue show wide variation. Employing a paid child‐minder is widely practiced in White households, whereas this concept is alien to the majority of ethnic minorities, who are more dependent upon their friends and families. Likewise, lack of health insurance acts as a barrier as there are fewer ethnic minority patients who are insured, thus reducing their chances of being recruited from treatment facilities. We must bear this in mind that culture still plays an important part in the genesis of these problems and the presenting nature may be the same yet there are culture specific intricacies that need special handling and will not be overcome by just employing simple solutions across the board for the whole sample.

It is clear from the results that some of the barriers are comparatively easier to address than others and can be easily overcome. Participants’ fear of being labelled as mentally ill may be a comparatively greater deterrent in ethnic minorities than in the general population, because of the added fear of families being stigmatized. Working with local ethnic community organizations and involving ethnic media helps in facilitating this process. This liaison also helps in getting families on board to encourage recruitment. But however this may reinforce traditional power relationships that are associated with the oppression particularly of ethnic women and raise concerns about confidentiality; particularly when the subjects are stressed due to family related problems or when they do not want to share their health issues like history of self‐harm.

It is here that the cultural competence of the main investigators and the field research workers in particular becomes critically important. Financial constraints and availability may not allow cultural matching of research staff yet training them on how to approach, invite and recruit ethnic minority subjects is extremely important. Extra human and financial resources will be needed and must be catered for in advance. This will help in preparing multilingual study materials and tailoring interventions to the needs of ethnic subjects.

As the recruitment process is multifactorial, no matter what investigators do, there will always be certain barriers that will be difficult to overcome. Psychopathology/substance misuse, domestic violence, lack of insurance and underutilization of mental health services (Table 2) are those difficult to modify factors. It can be said about certain barriers that making a few small changes in recruitment procedures and making extra provisions can lead to positive impact on ethnic minority recruitment. It is also evident that as the barriers are interrelated; therefore it may be necessary to simultaneously address several barriers to get desired results. Alternatively, it can be argued that it is more likely that making adjustments to overcome single barriers may be sufficient to positively affect multiple barriers.

Our review has provided us with a framework of barriers that is more sensitive to the needs of mental health research, based on the premise that the issues are different as compared to other health and social research. This will hopefully help in generating tailor made solutions, specifically for mental health research related barriers. Yancey et al. (2006) have already reviewed existing barriers to research in general health conditions and described to an extent possible solutions as well. Their review has generated overarching broad categories of barriers and possible solutions, however, our review provides in depth detailed sub‐categories. We have attempted to categorize the barriers to better understand the process and enable us to start exploring solutions to the barriers. This resulted in generating as many barriers as possible rather than amalgamating them, so that future researchers have a larger framework from which to highlight barriers and come up with pre‐emptive solutions. We hope that this way, the framework will be transferable and applicable to other ethnic groups outside of the United States. It should be reiterated again that the categories used in this review are not mutually exclusive nor ethnic specific, they are dependent upon each other which accounts for some repetition. There is undoubtedly an overlap in the barriers whilst they remain distinct in their own description.

It is noticeable that nine papers meeting out inclusion criteria are all from the United States with participants that were migrants typical for the United States. That said, the barriers were common across many of the studies and the issues that arose are universal issues that would be applicable elsewhere as well. Although there are no studies from Europe, researchers can use these categories as a framework to explore possible barriers to any other ethnic population and generate solutions based on clinical and research experience.

Conclusion

Under recruitment of ethnic minorities has an obvious implication for the generalization of the research findings and subsequent provision of health services and utilization by ethnic groups. By keeping out large ethnic populations from research we are dramatically reducing the pool of eligible participants leading to under recruitment and more importantly making our samples become non‐representative with reduced generalizability of the results.

There is a need to incorporate facilitators to recruitment by organizing researcher training and resource allocation; so that this becomes a pre‐emptive measure to counteract barriers rather than a post‐event reflection on what the barriers were. We need to be aware of the barriers at protocol stage and have the technical and financial resources in place. Once the project is underway, staff training, community engagement and intervention adaptation will need to be implemented. The effects of these on recruitment rate should be regularly reviewed and if these facilitators make an insufficient effect on recruitment rates and new barriers are encountered, then these need to be looked into and solutions generated.

We did not find any trials that tested interventions for enhancing recruitment of ethnic groups. Designing nested studies within randomized controlled trials (RCTs) would be valuable in gauging the effect of different recruitment strategies and will facilitate future research.

It is difficult to ascertain the extent to which prejudices do exist and how they affect recruitment either arising from researchers or from clinical services. The ethnicity of the researcher must also be taken into account as this prejudice could be assumed to be eradicated should the participant be of the same ethnicity as the researcher. It can be concluded from this that it takes extra efforts to recruit participants from ethnic minorities and with this comes additional costs to the research. It is therefore important that researchers take this into consideration within the planning stages and financial costing of the research.

References

- Aliyu M.H., Calkins M.E., Swanson C.L.J., Lyons P.D., Savage R.M., May R., Wiener H., Devlin B., Nimgaonkar V.L., Ragland J.D., Gur R.E., Gur R.C., Bradford L.D., Edwards N., Kwentus J., McEvoy J.P., Santos A.B., McCleod‐Bryant S., Tennison C., Go R.C.P., On behalf of the PAARTNERS study group (2006) Project among African‐Americans to explore risks for schizophrenia (PAARTNERS): recruitment and assessment methods. Schizophrenia Research, 87(1–3), 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arean P.A., Alvidrez J., Nery R., Estes C., Linkins K. (2003) Recruitment and Retention of Older Minorities in Mental Health Services Research. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K., McKenzie K., Rasul F. (2007) Rates, risk factors & methods of self harm among minority ethnic groups in the UK: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan M., Begg M.D., Brown A., Schaefer C., Sohler N., Insel B., Vella L., Susser E. (2007) Race and risk of schizophrenia in a US birth cohort: another example of health disparity? International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(4), 751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Kramer E.J., Chen T., Chung H. (2005) Engaging Asian Americans for mental health research: challenges and solutions. Journal of Immigrant Health, 7(2), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J., Husain N., Webb R., Waheed W., Kapur N., Guthrie E., Appleby L. (2006) Self‐harm in the UK: differences between South Asians and Whites in rates, characteristics, provision of service and repetition. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(10), 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon P., Kirkbride J., Morgan C., Dazzan P., Morgan K., Lloyd T., Hutchinson G., Tarrant J., Lun A., Fung W., Holloway J., Mallett R., Harrison G., Leff J., Jones P., Murray R. (2006) Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in ethnic minority groups: results from the MRC AESOP Study. Psychological Medicine, 36(11), 1541–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J.G., Howerton M.W., Lai G.Y., Gary T.L., Bolen S., Gibbons M.C., Tilburt J., Baffi C., Tanpitukpongse T.P., Wilson R.F., Powe N.R., Bass E.B. (2008) Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer, 112(2), 228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher‐Thompson D., Singer L.S., Depp C., Mausbach B.T., Cardenas V., Coon D.W. (2004) Effective recruitment strategies for Latino and Caucasian dementia family caregivers in intervention research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12(5), 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gater R., Tomenson B., Percival C., Chaudhry N., Waheed W., Dunn G., Macfarlane G., Creed F. (2009) Persistent depressive disorders and social stress in people of Pakistani origin and white Europeans in UK. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(3), 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Commission . (2005) Count Me In 2005. London: Healthcare Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey J.D. (2000) Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among Central American immigrants. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 30(2), 125–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain‐Gambles M., Atkin K., Leese B. (2004) Why ethnic minority groups are under‐represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 12(5), 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le H.N., Lara M., Perry D.F. (2008) Recruiting Latino women in the U.S. and women in Mexico in postpartum depression prevention research. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 11(2), 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loue S., Sajatovic M. (2008) Research with severely mentally ill Latinas: successful recruitment and retention strategies. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(2), 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinert J.A., Blehar M.C., Peindl K.S., Neal‐Barnett A., Wisner K.L. (2003) Bridging the gap: recruitment of African‐American women into mental health research studies. Academic Psychiatry, 27(1), 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J. 1996. Introduction to the special section on recruiting and retaining minorities in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 64(5), 848–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J., Organista K.C., Azocar F., Munoz R.F., Lieberman A. (1996) Recruiting and retaining low‐income Latinos in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(5), 868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J., Duan N., Sherbourne C., Schoenbaum M., Lagomasino I., Jackson‐Triche M., Wells K.B. (2003) Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research, 38(2), 613–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh A., Panesar S.S., Lasserson T., Netuveli G. (2004) Recruitment of ethnic minorities to asthma studies. Thorax, 59(7), 634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E.E., Neighbors H.W. (1996) Recruitment and retention of African American patients for clinical research: an exploration of response rates in an urban psychiatric hospital. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(5), 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau . (2009) Current population survey, annual social and economic supplement, ethnicity and ancestry statistics branch, population division. http://www.census.gov

- Waheed W., Husain N., Creed F., Bhui K. (2003) Psychiatric services for ethnic minority groups: a third way? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(6), 562–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey A.K., Ortega A.N., Kumanyika S.K. (2006) Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]