Abstract

This paper provides up‐to‐date data on service use for mental health problems and disorders among adults aged 18‐79 years in Germany derived from the Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1‐MH; N=4483). Data are based exclusively on self‐report. Respondents were examined by clinically trained interviewers with a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview DIA‐X/M‐CIDI to assess diagnoses according to the criteria of DSM‐IV‐TR. Service use, i.e. contact to mental health care services, due to mental health problems was assessed for the past 12 months and lifetime, by type of sector and type of institution. Among respondents with a 12‐month diagnosis of a mental disorder, 23.5% of the women and 11.6% of the men reported any service use in the past 12 months. Service use depends on type of diagnosis, comorbidity and socio‐demographic characteristics. Lowest 12‐month utilization rates were found for substance use disorders (15.6%; lifetime use 37.3%), highest for psychotic disorders (40.5%; lifetime 72.1%). Further, a considerable time lap was found between disorder onset and subsequent service use among the majority of cases with anxiety and mood disorders. This paper provides self‐reported epidemiological data on mental health service use in Germany, complementing administrative statistics and the predecessor mental health module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS‐MHS) from 1998. Despite considerable changes in the mental health field in Germany and the existence of a comprehensive mental health care system without major financial barriers, we find no indications of substantially higher utilization rates for mental disorders as compared to other comparable European countries. Further, no indications of major overall changes in utilization rates are apparent. To pinpoint areas with unmet needs, more detailed analyses of the data are needed taking into account type, frequency, and adequacy of service use and treatment of mental disorders. Appropriately matched comparisons with the GHS‐MHS are needed to identify changes in patterns of utilization and interventions by type of disorder. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: mental health care, service use, service utilization

Introduction

There is consistent evidence from epidemiological research around the world that mental disorders are highly prevalent (Kessler et al., 2008) and a major contributor to the total disability burden (WHO, 2011; Wittchen et al., 2011; Vos et al., 2013). There is, despite a considerable degree of variability by country and region, also convergent evidence that the majority of those with mental disorders are not treated and among the majority of treated patients, treatment often occurs delayed and frequently not in accordance with established guidelines (Wittchen et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2005). This situation of low treatment rates also seems to apply to European countries and even to countries that offer comprehensive mental health care without major financial barriers of access (Wittchen et al., 2011; Wittchen et al., 2005). A recent study report of the European Brain Council (Wittchen et al., 2011) concluded that overall the quality and detail of existing findings by country is unsatisfactory and incomplete, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. This paper responds to the need of improved and up‐to‐date epidemiological data of mental health care service use by country by describing the situation in Germany.

Substantial routine administrative data and reports are available for Germany regarding mental health service use (e.g. Badura et al., 2013; TK, 2013; DAK‐Gesundheit, 2013). Such analyses have been interpreted to indicate increasing mental health care utilization rates in Germany (Gaebel et al., 2012a). Gaebel et al. (2013) also recently presented data from a large‐scale analysis of health insurance data involving almost 10 million persons. Main findings were that in the years 2005–2007 one third (33%) had a recorded contact with any provider associated with an ICD‐10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) diagnosis of at least one mental disorder. The vast majority was seen in the outpatient sector (95.7%). Most persons with a diagnosis of a mental disorder had at least one additional diagnosis of a somatic disease, the majority had more than two diagnoses of mental disorders and the most types of disorders were recorded not in mental health services but in primary care and other medical specialties.

Beyond such routine administrative epidemiological data, with their typical restrictions (i.e. variable diagnostic standards, confounding with reimbursement issues), internationally comparable data about health care utilization patterns in a nationally representative sample of the adult German population are rare. Such data became first available from the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey (GNHIES‐98; Bellach et al. 1998; Robert‐Koch‐Institut, 2002) and its Mental Health Supplement (GHS‐MHS; Jacobi et al., 2002). This study, using data from 1996 to 1998, found that among those with a DSM‐IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) mental disorder in the past year, 40.5% reported having sought professional help due to mental health problems in their lifetime (Jacobi et al., 2004). Additional data became available about five years later from a multinational European survey, including a representative sample of German citizens as part of the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (ESEMeD Germany; Kessler et al., 2008; Alonso et al., 2004). This study found that 26.0% of the respondents with a 12‐month mental disorder reported to have talked with a health professional about mental health problems in the prior 12 months before the survey. Thus, the available data evidence for Germany is restricted to older data, reflecting the situation in the late 1990s and early 2000. These data do not reflect the partly substantial changes in the German mental health care system, implemented since 1999. Changes might be expected due to a number of national and European campaigns to raise awareness about the size and burden of mental disorders and the need for better and more frequent treatment (European Commission, 2005), and specific measures to improve the German mental health care system such as the inclusion of psychological psychotherapists as independent providers for mental health problems, accessible to all. Since then the number of psychotherapists have increased by about 33% (between 2000 and 2010) adding to the already existing psychotherapy provider system (psychiatrists, medical psychotherapists) offering diagnosis and treatment, covered by the mandatory health insurance regulations without payment by the patient (KBV, 2001, 2011).

This paper capitalizes on the availability of the second German large‐scale general population survey (German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults, Mental Health Module, DEGS1‐MH; Jacobi et al., 2013, 2014), completed in 2012 with similar assessment strategies as a previous survey in 1998 as well as most international community studies conducted in the past two decades. Thus, the data reported allow for national and cross‐national comparisons and complement the available evidence from administrative data (Gaebel et al., 2013).

Aims

We report nationally representative data for Germany on the use of health care services due to mental health problems (a) for the total German population, (b) for persons without the diagnosis of a mental disorder as assessed in this study, and (c) for cases with mental disorders according to the criteria of DSM‐IV‐TR. The utilization data are exclusively based on self‐report by the respondent and do not take into account in any way administrative data or clinical information by providers. Although the focus of this paper is on utilization in the past 12 month preceding the interview and respondents diagnostic status in the past 12‐month, we also report data for respondents with lifetime diagnoses. This is because otherwise we might exclude for example subjects in treatment that have improved, not meeting diagnostic criteria anymore during the past 12 months.

Service use rates are presented for different types of service providers in different health care sectors, i.e. the inpatient, the outpatient, and the complementary sector. We report utilization rates due to mental health problems, including psychosomatic or substance related problems as reported by the subject, irrespective of the type, frequency, and adequacy of the possible intervention, and also irrespective of any diagnosis of a mental disorder that might have been prescribed by a medical doctor or another health professional the respondent might have seen. We further examine socio‐demographic correlates of service use as well as differences in service use rates by type of mental disorder and comorbidity with other mental disorders and present information on the estimated median time period between the onset of a mental disorder and first reported service use for cases with a 12‐month diagnosis.

Methods

The DEGS1‐MH study design and sampling within the DEGS1 survey has been presented in detail in previous publications (Jacobi et al., 2013; Kamtsiuris et al., 2013; Scheidt‐Nave et al., 2012). The study proposal, field procedures, and information for respondents of DEGS1 were approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committees responsible for DEGS1 (Charité, Berlin) and for DEGS1‐MH by the Ethics Board of the Technische Universität Dresden, respectively.

Sample and weighting

A random sample of persons aged 18 to 79 years stratified for sex, age and geographical location was drawn from local population registries. First, among all German municipal communities, 180 study sample points were determined. Second, participants were randomly selected from local population registries covering the 180 sample points, supplemented by former participants of the predecessor GNHIES‐98 study, who had neither died nor moved abroad and who had agreed to renewed contact. Gross sample for DEGS1‐MH was a total of N = 7116 DEGS1 participants aged 18–79 years with complete assessment (interview and examinations). In DEGS1, the response rate was 62% for the former participants of the GNHIES‐98 study and 42% for the new DEGS1 participants (Kamtsiuris et al., 2013). For DEGS1‐MH, all DEGS1 participants were eligible who met the following criteria: (a) age 18–79; (b) complete DEGS1 assessment consisting of the medical interview and examination, laboratory tests, and self‐report scales; (c) informed consent to be re‐contacted by the independent DEGS1‐MH study team for the mental health supplement; (d) sufficient language skills to complete the mental health assessment, and (e) availability during the assessment period. Persons who were institutionalized during the whole assessment period were thus not included. A total of 1089 DEGS1 participants were not eligible (987 provided no informed consent to be re‐contacted, 37 had insufficient language skills, 14 were long‐term hospitalized, six had died since the DEGS1 main survey, and for 45 no valid address for contact was available). The total DEGS1‐MH study sample consisted of 5317 participants of which 4483 completed the full DEGS1‐MH assessment. Thus, N = 834 completed the core diagnostic part of the assessment package, based on the stem screening questions (CID‐S; Wittchen et al., 1999) of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), because of time constraints (N = 450), health problems (N = 49), and other reasons (N = 335).

Measures

Diagnostic status

Within the comprehensive DEGS1‐MH assessment platform, the DEGS CIDI (DIA‐X/M‐CIDI) was the main component. This fully structured algorithm‐ and computer‐based interview (Lachner et al., 1998; Reed et al., 1998; Wittchen et al., 1991, 1997; Wittchen, 1994) is a modified version of the World Health Organization CIDI (Kessler et al., 2004). Symptoms and syndromes according to the criteria of DSM‐IV‐TR are reliably assessed for different time frames (four‐week, 12‐month, and lifetime for selected disorders). In this paper, CIDI‐diagnoses are presented for two time periods, i.e. lifetime and 12‐month. Twelve‐month mental disorders refer to the time period of the past 12 months preceding the diagnostic interview while the time span of lifetime mental disorders here is defined as the whole period of the respondent's life, including the past 12 months. Whether the respondent is a “case” was exclusively classified by the DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria in the CIDI‐interview, thus irrespective of the existence of a diagnosis of a mental disorder recorded in the clinical daily routine.

Mental disorders covered are: mental disorder due to a general medical condition or substance‐induced disorders, substance‐related disorders (nicotine dependence, alcohol‐ and medication abuse and dependence), possible psychotic disorders (F2 and other groups of psychotic disorders; screening without further differential diagnosis), mood disorders (major depression, dysthymia, bipolar I and II disorder), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobias), obsessive‐compulsive disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder, somatoform disorders (pain disorder and undifferentiated somatoform disorder as measured by the Somatic Symptom Index, SSI4,6), and eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder). Onset of disorder was assessed according to the convention of the CIDI: recent onsets were recorded by weeks and months, distant onsets (i.e. above one year distance from diagnostic interview) by years.

Service use

The mental health service use module consisted of a series of about 40 questions. The module was only administered when the module's “gateway” question was endorsed: Have you ever visited/contacted any of the health care institutions [as listed in the respondent's booklet] because of mental health, psychosomatic, or substance use problems, either by yourself, or by advise of others, e.g. medical doctors, relatives, or your partner? In addition many subsequent questions were gated questions which are only asked if previous questions were endorsed (such as when a specific type of provider was seen). The module includes the following domains regarding service utilization: help‐seeking behavior (thinking about and/or contacting a service due to mental health problems); service utilization by type of sector and type of service provider; date of first and last contact; information on treatments (type, frequency, duration, and treatment satisfaction); drug treatment and type of medication; and treatment discontinuation. In this paper, we focus on the following measures:

Service use: Contact to professional health services due to mental health problems, irrespective of the type, frequency, and adequacy of the possible intervention, separately for the 12 months prior the diagnostic interview (12 month use) or at any point in time including the past 12 months (lifetime use).

Service sector grouped into the inpatient, the outpatient, and the complementary sector.

Service providers/institutions included 27 types of health care or mental health care institutions and service providers that were listed in the respondent's booklet (see Table 1). Inpatient institutions included all types of psychiatric, neurologic, psychosomatic and psychotherapeutic hospitals, respectively, departments, inpatient institutions for alcohol, medication or drug problems, as well as day care centers and homes/or other types of sheltered environments. Outpatient institutions were general practitioners, mental health specialists (i.e. psychiatrists, medical or psychological psychotherapists, or other psychologists), psychiatric or psychotherapeutic outpatient clinics, (social‐) psychiatric services, and other outpatient institutions (such as specialist medical care providers in outpatient care settings). Respondents were instructed to report contact to general practitioners only if reason for visit were any mental health problems. The complementary sector included professional counseling centers (i.e. for students, education, marriage, or health problems like sexual problems, AIDS support, drug‐ or alcohol use), sheltered housing groups, professional education for the disabled, special working places for the disabled, transitional homes, telephone counseling, and self‐help organizations.

Table 1.

Type of sectors and service providers assessed in DEGS1‐MHa

| Sector A: Inpatient health care institutions |

| Psychiatric hospital or department |

| Hospital or department for neurology |

| Psychotherapeutic or psychosomatic hospital |

| Hospital or department for substance abuse |

| Daycare clinic |

| Home for children |

| Other inpatient institutions |

| Sector B: Outpatient health care institutions |

| General practitioner (if reason was mental health problem) |

| Psychiatrist |

| Psychotherapist |

| Other psychologist |

| Psychiatric or psychotherapeutic outpatient clinic |

| (Social‐) psychiatric service |

| Other outpatient institution |

| Sector C: Complementary institutions |

| Counseling centers |

| ‐ students |

| ‐ education (children, adolescents, parents) |

| ‐ marriage, partnership, life |

| ‐ sexual problems |

| ‐ AIDS support |

| ‐ drug or alcohol use |

| ‐ other counseling centers |

| Self‐help organizations |

| Sheltered housing groups |

| Professional education for the disabled |

| Special working places for the disabled |

| Transitional homes |

| Telephone counseling |

Twenty‐seven institutions as listed in the respondents booklet.

Due to reliance on self‐report it should be highlighted that reports are based on the respondent's perception and recall. Therefore, erroneous designations of the types of providers by the respondent cannot be excluded: In particular “psychiatrists” are frequently qualified and labeled as specialist for “psychiatry and psychotherapy” in Germany; difficulties of respondents in distinguishing between psychiatry and psychotherapy might be a consequence. In some cases even the differentiation between psychiatrist and psychologist might be confused by the respondent.

If the entry question was endorsed respondents were prompted to report all of the services that were contacted at any point in time. For each type of professional seen, information was recorded on the age of the first and the recency of the last contact which was used to distinguish between service use within and before the last 12 months.

Correlates

Socio‐economic status (SES) was operationalized as an aggregate measure of educational level, current job position, and income (Lampert et al., 2013a, 2013b). SES was divided into three categories (20% high – 60% medium – 20% low). Also the regional variable urbanization was analyzed (< 20,000 inhabitants, 20,000–100,000, 100,000–500,000, > 500,000).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were based on the 4483 respondents with full diagnostic assessment. Data were calculated using weights to reflect sampling probabilities and systematic non‐participation. Differences in service use rates by age and gender and further socio‐demographic correlates were tested with odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regressions with 95% confidence intervals. Comorbidity of mental disorders was defined as the number of mental disorders per person within the last 12 months.

Among the service users, survival analyses with Kaplan–Meier‐estimates were conducted to estimate the duration in years between earliest reported onset of any anxiety and mood disorder, respectively, and the time of any subsequent use of health care services due to mental health problems (while taking into account censoring due to date of observation). This was done among the 12‐month cases of the respective disorder. Participant's records of service use prior to disorder onset were not considered here. Statistical inference for weighted data was based on the robust Huber–White sandwich estimator (Royall, 1986).

Results

In the total sample of 4483 participants (Figure 1), 24.5% reported any lifetime service use with mental health care professionals because of mental health problems, including psychosomatic or substance use‐related problems. Of the subjects who never met criteria of any CIDI mental disorder, 12.9% reported to have ever consulted a professional health care provider. Among those meeting criteria for any CIDI lifetime diagnosis and with information on service use (N = 1668), 41.8% reported any service use of the mental health care services ever and 16.0% within last 12 months. Among those with a 12‐month mental disorder with information on service use (N = 1186), 42.6% reported any lifetime use and 18.9% in the past 12 months.

Figure 1.

Lifetime and 12‐month service use rates in the total sample and among those with and without mental disorders. Numbers reported for respondents with information on diagnostic status and service use.

Among those with a lifetime diagnosis of a mental disorder (Table 2), women reported a considerably higher rate of lifetime service use than men in all age groups (47.8% versus 33.6%, p < 0.001). Among the 12‐month cases, rates are particularly low among the elderly with mental disorders, of which 14.8% of women and 4.0% of men reported service use in the past year.

Table 2.

Service use rates due to mental or substance use‐related problems by age and gender

| Lifetime service use rate | 12‐month service use rate | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %w | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | p‐Value | N | %w | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | p‐Value | |||||

| Respondents with lifetime mental disorders (N = 1677) b | ||||||||||||||||

| Women | 494 | 47.8 | 43.7 | 51.9 | 186 | 20.2 | 16.9 | 23.9 | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 94 | 43.4 | 35.1 | 52.1 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 1.15 | 0.172 | 42 | 22.4 | 15.6 | 31.1 | 1.25 | 0.71 | 2.19 | 0.434 |

| 35–49 | 129 | 49.4 | 41.8 | 57.1 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 1.42 | 0.733 | 51 | 21.9 | 16.0 | 29.2 | 1.22 | 0.73 | 2.04 | 0.458 |

| 50–64 | 178 | 51.2 | 44.0 | 58.4 | Ref. | 66 | 18.7 | 14.0 | 24.6 | Ref. | ||||||

| 65–79 | 93 | 47.4 | 38.0 | 57 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 1.39 | 0.534 | 27 | 15.6 | 9.3 | 24.9 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 1.58 | 0.522 |

| Men | 228 | 33.6 | 29.1 | 38.4 | 69 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 13.6 | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 38 | 23.5 | 16.3 | 32.7 | 0.46* | 0.26 | 0.83 | 0.009 | 13 | 7.5 | 3.9 | 13.8 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 1.54 | 0.323 |

| 35–49 | 68 | 36.3 | 28.0 | 45.6 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 1.46 | 0.583 | 24 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 21.5 | 1.28 | 0.60 | 2.75 | 0.519 |

| 50–64 | 74 | 39.8 | 31.5 | 48.7 | Ref. | 23 | 11.1 | 6.7 | 17.8 | Ref. | ||||||

| 65–79 | 48 | 38.5 | 27.6 | 50.8 | 0.95 | 0.52 | 1.75 | 0.866 | 9 | 6.5 | 2.9 | 13.9 | 0.56 | 0.21 | 1.51 | 0.249 |

| Respondents with 12‐month mental disorders (N = 1194) c | ||||||||||||||||

| Women | 369 | 48.7 | 43.9 | 53.4 | 163 | 23.5 | 19.6 | 28 | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 79 | 43.6 | 34.4 | 53.1 | 0.60* | 0.36 | 0.99 | 0.046 | 41 | 25.5 | 17.7 | 35.2 | 1.24 | 0.68 | 2.26 | 0.489 |

| 35–49 | 95 | 49.4 | 40.4 | 58.4 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 1.24 | 0.264 | 47 | 27.5 | 20.0 | 36.5 | 1.37 | 0.78 | 2.41 | 0.276 |

| 50–64 | 133 | 56.4 | 48.0 | 64.5 | Ref. | 55 | 21.7 | 15.8 | 29 | Ref. | ||||||

| 65–79 | 62 | 45.9 | 35.2 | 56.9 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 1.14 | 0.134 | 20 | 14.8 | 8.6 | 24.1 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 1.28 | 0.199 |

| Men | 145 | 33.2 | 27.7 | 39.1 | 56 | 11.6 | 8.5 | 15.7 | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 29 | 25.2 | 16.5 | 36.5 | 0.48* | 0.24 | 0.95 | 0.034 | 12 | 9.3 | 4.7 | 17.5 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 1.54 | 0.307 |

| 35–49 | 41 | 35.9 | 25.7 | 47.6 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 1.51 | 0.484 | 17 | 15.8 | 9.1 | 26.1 | 1.15 | 0.51 | 2.59 | 0.742 |

| 50–64 | 52 | 41.4 | 31.3 | 52.3 | Ref. | 22 | 14.1 | 8.8 | 21.8 | Ref. | ||||||

| 65–79 | 23 | 31.7 | 18.6 | 48.4 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 1.49 | 0.313 | 5 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 10.6 | 0.26* | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.021 |

Odds ratios (OR) from logistic regression and 95% confidence intervals (CIs): p < 0.05. Global test for interaction sex*age group: F(3, 1183) = 0.60; Prob > F = 0.6163.

Nine missings of respondents with lifetime mental disorders without information on service use.

Eight missings of respondents with 12‐month mental disorders without information on service use. * indicates statistical significance for p‐value under .05.

Socio‐demographic correlates of service use

Service use rates among cases with a lifetime mental disorder were significantly higher among the never married (58.5% compared to married 39.2%), among those without current partnership (45.9% compared to those with current partnership 40.0%), and among persons not employed (i.e. unemployed, retired, student) versus the employed (47.7% versus 38.0%). No differences were found with regard to urbanization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Socio‐demographic correlates for lifetime service use among cases with lifetime mental disordersa

| Correlate in sample (N = 1668) | Association with any service use (N = 722) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %w | N | %w | ORb | 95% CI | p‐Value | |||

| Gender | Men | 664 | 42.2 | 228 | 33.7 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.000 |

| Women | 1004 | 57.8 | 494 | 47.8 | Ref. | ||||

| Age | 18–34 | 358 | 28.9 | 132 | 34.8 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 0.007 |

| 35–49 | 448 | 30.8 | 197 | 43.71 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 0.537 | |

| 50–64 | 518 | 24.8 | 252 | 46.31 | Ref. | ||||

| 65–79 | 344 | 15.5 | 141 | 44.28 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 1.29 | 0.509 | |

| Marital status | Married | 910 | 50.6 | 372 | 39.2 | Ref. | |||

| Never married | 301 | 17.0 | 172 | 58.5 | 2.05 | 1.44 | 2.92 | 0.000 | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 457 | 32.4 | 178 | 37.2 | 1.26 | 0.83 | 1.91 | 0.272 | |

| Current partnership | Yes | 1181 | 68.4 | 487 | 40.0 | Ref. | |||

| No | 487 | 31.5 | 235 | 45.9 | 1.45 | 1.08 | 1.95 | 0.014 | |

| Educational levelc | Low | 463 | 34.1 | 188 | 41.3 | 0.92 | 0.67 | 1.28 | 0.638 |

| Medium | 876 | 53.9 | 370 | 40.9 | Ref. | ||||

| High | 315 | 11.9 | 160 | 49.4 | 1.37 | 0.97 | 1.94 | 0.077 | |

| Socio‐economic statusd | Low | 267 | 23.1 | 113 | 41.8 | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.56 | 0.641 |

| Medium | 989 | 59.5 | 416 | 41.2 | Ref. | ||||

| High | 398 | 17.4 | 189 | 45.3 | 1.22 | 0.90 | 1.66 | 0.200 | |

| Employment | Yes | 959 | 60.1 | 404 | 38.0 | Ref. | |||

| Noe | 709 | 39.9 | 318 | 47.7 | 1.64 | 1.19 | 2.25 | 0.002 | |

| Urbanization | < 20,000 inhabitants | 287 | 13.7 | 113 | 39.3 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 1.22 | 0.325 |

| 20,000 to < 100,000 | 363 | 22.9 | 163 | 41.7 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 1.31 | 0.641 | |

| 100,000 to < 500,000 | 493 | 28.8 | 214 | 41.9 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 1.31 | 0.713 | |

| > 500,000 | 526 | 34.6 | 232 | 42.8 | Ref. | ||||

DEGS1‐MH weighted data from respondents with a lifetime mental disorder and information on service use (N = 1668).

Odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), controlled for age and sex.

CASMIN classification.

Index of social class (Lampert et al., 2013a, 2013b) derived from information on education, income and current (job) position.

No: unemployed, retired, student.

Service use by type of sector and type of institution

Among cases with a lifetime mental disorder (Table 4), outpatient mental health care settings were used most frequently (34.8% reported any lifetime service use and 13.6% during the past 12 months). Rates for inpatient service use were 13.0% lifetime use and 1.9% past 12 months use. Rates for the complementary sector were 9.2% and 3.1%, respectively. Among the outpatient service providers, psychotherapists were reported most often (lifetime service use by 19.4% of all cases with a lifetime diagnosis of a mental disorder, 12‐month service use 5.9% respectively) followed by the general practitioner (13.6% of lifetime cases reported lifetime use compared to 4.5% in the preceding 12 months) and the psychiatrist (11.8% and 4.5%, respectively). Service use rates among cases with a 12‐month diagnosis of a mental disorder showed similar patterns (right part of Table 4).

Table 4.

Service use by type of sector and type of institution among respondents with diagnosis of a mental disorder

| Among lifetime cases (N = 1677) | Among 12‐month cases (N = 1194) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime service use | Past 12 month service use | Lifetime service use | Past 12 month service use | |||||

| N | %w | N | %w | N | %w | N | %w | |

| Inpatient health care institutions | 226 | 13.0 | 33 | 1.9 | 181 | 15.2 | 28 | 2.3 |

| Psychiatric hospital or department | 74 | 4.8 | 10 | 0.5 | 62 | 5.7 | 10 | 0.7 |

| Hospital or department for neurology | 25 | 1.3 | 5 | 0.2 | 17 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.1 |

| Psychotherapeutic or psychosomatic hospital | 110 | 5.9 | 13 | 0.9 | 88 | 7.0 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Hospital or department for substance abuse | 18 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Daycare clinic | 28 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.2 | 24 | 2.5 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Home for children | 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other inpatient institutions | 20 | 1.4 | 5 | 0.3 | 18 | 1.8 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Outpatient health care institutions | 605 | 34.8 | 218 | 13.6 | 425 | 34.8 | 188 | 15.9 |

| General practitioner | 245 | 13.6 | 84 | 4.5 | 178 | 13.5 | 78 | 6.0 |

| Mental health specialist | 488 | 28.7 | 150 | 9.6 | 346 | 29.5 | 130 | 11.5 |

| Psychiatrist | 206 | 11.8 | 70 | 4.5 | 146 | 11.7 | 60 | 5.3 |

| Psychotherapist | 330 | 19.4 | 88 | 5.9 | 246 | 21.3 | 78 | 7.4 |

| Other psychologists | 54 | 3.4 | 8 | 0.6 | 35 | 2.9 | 8 | 0.8 |

| Psychiatric or psychotherapeutic outpatient clinic | 56 | 3.4 | 17 | 1.2 | 42 | 3.7 | 14 | 1.2 |

| Social psychiatric services | 10 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Other outpatient institutions | 12 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Complementary health care institutions | 133 | 8.3 | 31 | 2.6 | 98 | 9.6 | 28 | 3.5 |

| Counseling centers | 118 | 7.7 | 24 | 2.3 | 88 | 9.0 | 22 | 3.1 |

| Self‐help groups | 19 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.0 | 14 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other complementary institutions | 13 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.1 | 10 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.1 |

Service use by disorder and comorbidity

Service use rates varied considerably between the diagnostic groups of mental disorders (Table 5). Cases with a lifetime psychotic disorder (lifetime service use rate 59.8%; past 12 month service use rate 32.0%) reported the highest service use rates; those with any substance use‐related mental disorder the lowest rates (lifetime service use 38.4%, 12 month use 13%). Service use rates in the 12‐month cases were somewhat higher than in the lifetime cases, ranging from over 72% lifetime use in possible psychotic and in panic disorders down to 21.7% in alcohol abuse.

Table 5.

Lifetime and 12 month service use by type of specific mental disordersa

| Lifetime DSM‐IV diagnosis (N = 1677) | 12‐month DSM‐IV diagnosis (N = 1194) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime service use (N = 722) | 12 month service use (N = 255) | Lifetime service use (N = 514) | 12 month service use (N = 219) | |||||

| N | %w | N | %w | N | %w | N | %w | |

| Any mental disorder due to general medical condition or substance induced disorders | 44 | 55.8 | 15 | 19.9 | 20 | 53.2 | 9 | 25.9 |

| Any substance use disorder inclusive nicotine dependenceb | 385 | 33.3 | 143 | 12.7 | 231 | 37.3 | 98 | 15.6 |

| Any substance use disorder without nicotine dependenceb | 132 | 38.4 | 49 | 13.0 | 93 | 42.6 | 36 | 15.8 |

| Alcohol abuse | 74 | 34.7 | 25 | 10.4 | 15 | 21.7 | 5 | 10.2 |

| Alcohol dependence | 72 | 53.0 | 26 | 16.5 | 49 | 48.8 | 15 | 12.9 |

| Medication abuse | 35 | 56.2 | 14 | 24.0 | 34 | 55.8 | 14 | 24.1 |

| Medication dependence | 26 | 59.2 | 13 | 30.3 | 11 | 60.5 | 7 | 34.3 |

| Possible psychotic disorderc | 115 | 59.8 | 51 | 32.0 | 62 | 72.1 | 31 | 40.5 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 344 | 48.7 | 149 | 22.3 | 300 | 48.0 | 140 | 23.5 |

| Panic disorderd | 125 | 67.6 | 54 | 31.8 | 67 | 72.6 | 36 | 41.8 |

| Agoraphobia | 105 | 61.1 | 55 | 31.4 | 98 | 64.0 | 52 | 33.2 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 56 | 69.2 | 32 | 40.7 | 53 | 69.1 | 32 | 42.6 |

| Social phobia | 68 | 70.1 | 45 | 46.0 | 64 | 69.7 | 44 | 48.2 |

| Specific phobiase | 175 | 44.1 | 69 | 18.9 | 175 | 44.1 | 69 | 18.9 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 64 | 42.7 | 28 | 17.5 | 62 | 44.1 | 27 | 18.2 |

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder | 120 | 56.7 | 53 | 25.9 | 59 | 61.6 | 29 | 31.0 |

| Any mood disorder | 391 | 55.8 | 156 | 24.2 | 228 | 57.4 | 122 | 32.9 |

| Major depressive disorder | 278 | 54.0 | 100 | 23.0 | 142 | 55.7 | 78 | 34.6 |

| Dysthymia | 112 | 62.4 | 68 | 42.5 | 109 | 62.7 | 66 | 42.6 |

| Bipolar I and II disorder | 69 | 67.1 | 37 | 29.9 | 40 | 68.4 | 25 | 37.4 |

| Any eating disorderf | 43 | 50.7 | 19 | 26.2 | 15 | 41.2 | 8 | 24.8 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 33 | 48.7 | 15 | 25.0 | 7 | 31.6 | 5 | 22.8 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 18 | 85.5 | 5 | 31.8 | 7 | 73.1 | 1 | 12.3 |

| Binge eating disorder | 3 | 52.5 | 3 | 52.5 | 2 | 51.3 | 2 | 51.3 |

| Any somotoform disorder/syndrome | 175 | 55.4 | 61 | 23.1 | 80 | 49.5 | 37 | 26.5 |

| SSI4/6 | 49 | 62.2 | 18 | 28.6 | 19 | 55.2 | 11 | 38.3 |

| Pain disorder | 141 | 54.8 | 52 | 23.9 | 68 | 49.0 | 31 | 25.8 |

| Any mental disorder (without nicotine dependence) | 722 | 41.8 | 255 | 16.0 | 514 | 42.6 | 219 | 18.9 |

Weighted data; DSM‐IV hierarchy rules were dropped.

Without illicit drug abuse/dependence (not assessed).

Screening for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders without further differential diagnosis; includes psychotic features occurring as part of mood disorders.

With or without agoraphobia.

Animal, natural environment, blood‐injection‐injury, and situational type.

Anorexia nervosa, atypical anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, atypical bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder.

Service use was strongly associated with the number of comorbid mental disorders (Figure 2). Service use rates of men equaled those of women only in highly comorbid cases. Among cases with comorbid unipolar depression, defined here as major depressive disorder or dysthymia, service use rates were higher compared to comorbid mental disorders without comorbid depression (lifetime service use rate 60.4% in cases with any comorbidity of mental disorders including 12‐month diagnosis of depression versus 44.3% without 12‐month diagnosis of depression; 12 month service use rate 39.5% in cases with any comorbidity of mental disorders including 12‐month diagnosis of depression versus 19.6% without 12‐month diagnosis of depression).

Figure 2.

(a) Association between comorbidity and 12 month service use among respondents with a diagnosis of a 12‐month mental disorder. (b) Service use of cases with comorbid mental disorders with and without (w/o) comorbid unipolar depression (i.e. major depressive disorder or dysthymia).

Time between disorder onset and service use

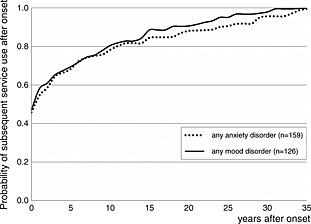

Figure 3 presents Kaplan–Meier curves among the service users showing the proportion of respondents with any anxiety and any mood disorder that eventually had a mental health care service use in years after the onset of the respective mental disorder. This was done among the 12‐month cases of the respective disorder. In the year of disorder onset, 45.8% of cases with any anxiety disorder, 47.1% of cases with any mood disorder reported contact with health care services due to mental health problems. The estimated time between first diagnosis and subsequent contact to mental health care services among those not making any treatment contact within the year of disorder onset, was 6 years for any anxiety disorder and 7 years for any mood disorder. Further analyses on the delay including all participants are available on request.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier‐estimates on time period between first disorder onset (12‐month diagnoses) and subsequent service use in years among cases that made service use. Any mood disorder includes major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar I and II disorder.

Discussion

The core findings are:

Although Germany ranks among the countries with the highest general health care utilization rates worldwide, the majority of men and women with mental disorders in Germany did not report having used any provider or service for mental health reasons. This result is at large consistent with the European survey by Alonso et al. (2004).

Among all respondents with a 12‐month diagnosis of any mental disorder, only 18.9% had used in the past year either any general health care or specialized mental health care service for mental health reasons. Rates are particularly low in men (11.6%) and among the elderly (65–79) women (14.1%) and elderly men (4.5%) with mental disorders.

Utilization rates differ though substantially by type of diagnosis: Particularly low 12‐month service use rates for 12‐month mental disorders were found for most substance use disorders (15.8%), bulimia nervosa (12.3%), and specific phobias (18.9%). Considerably higher rates were found for social anxiety disorder (48.2%), generalized anxiety disorder (42.6%), dysthymic disorder (42.6%) panic disorder (41.8%), and psychotic disorders (40.5%).

Utilization rates depended strongly on comorbidity. Service use rates steadily increased with the number of comorbid mental disorders, from an overall 11% in persons with only one mental disorder to over 40% in those with multimorbidity (four or more diagnoses).

There are considerable time lapses between the first onset of anxiety and mood disorders and subsequent service use in the health care system among persons with a 12‐month mental disorder, i.e. a median time period of 6 years for any anxiety and 7 years for any mood disorder among those not making treatment contact in the year of disorder onset.

Utilization is associated with socio‐demographic characteristics. Being never married, no current partnership, and not employed (i.e. unemployed, student, retired) was associated with higher prevalances of lifetime service use due to mental health problems.

According to respondent's self‐report, utilization of psychotherapists, medical or psychological, was reported more frequently than other types of specialized mental health providers.

Rates for inpatient care among persons with a lifetime diagnosis (13%) were high compared to other countries (Kessler et al., 2008).

These recent data from Germany appear to be similar to other countries with comprehensive mental health care (Alonso et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2008). Although one cannot equate the presence of a mental disorder directly with specific treatment needs, it is important to note that by definition of a mental disorder and its explicit diagnostic criteria as used in the present study, each diagnosis implies a need for an intervention (or at least further monitoring), may it be a diagnostic assessment with counseling, or the initiation of a psychiatric, a psychological, social, or psychopharmacological treatment. Given that Germany has a comprehensive health care and mental health system that even offers psychotherapy free of charge to the patient, it is remarkable that the utilization rates reported in our survey are not substantially higher than in other comparable countries. Ideally the majority of cases should have reported to have been in contact with at least one health care provider either lifetime or in the past 12 month. The finding that even a minimal intervention was not reported in the majority of cases and that many cases did not report any service use ever for mental health reasons and thus might never have been recognized by the health care system raises many questions: Are the self‐report data reliable? Did our standardized questions elicit valid and trustworthy responses? Why are the mental health utilization rates for primary care doctors so low – given that the majority of German citizens see their general practitioner at least once a year (Rattay et al., 2013)?

Although we cannot provide direct proof of reliability and validity for our assessment that is based on standard questions used in many similar surveys worldwide of this sort, there is at least indirect support for our findings. Due to administrative statistics from three health insurance companies, 33% of about 10 million insured persons in Germany (Gaebel et al., 2013) have a recorded visit to the health care system in connection with mental disorders as diagnosed by medical doctors in a three years time period. This number lies in the middle of our lifetime (39.7 and 42.6%) and our 12‐months estimate (18.9%). We assume that not all physician recorded diagnoses are also evident to the patient and further that many physicians might not feel responsible to recognize mental disorders. This corresponds to the findings based on self‐report in the present study. Probably some cases in our study might in fact be diagnosed and recorded as a patient by the provider but the respondent did either never notice, does not remember, or was reluctant to report this intervention in our study. However we assume, due to good acceptance and the low refusal rate in our study (Jacobi et al., 2013) that reluctance (e.g. due to fear of stigmatization) might not play a significant role. Rather, other factors, such as poor mental health literacy (Jorm, 1997) might be of greater relevance. Further difficulties arise from the fact that a clear distinction between the providers is sometimes hard to make by service users (e.g. in Germany also psychiatrists – trained as specialists in psychiatry and psychotherapy – and other medical specialists additionally trained in psychotherapy provide psychotherapeutic interventions). Further steps to investigate these issues include: (a) closer examination of the respondents who reported psychiatric or psychotherapeutic treatment in the DEGS1 main survey but not in the DEGS1‐MH mental health module; (b) analyzing further interview questions addressing reasons for not seeking treatment or counseling; (c) also more detailed examination in a subsample of respondents reporting no treatment (although having been at a general practitioner or psychiatrist) in future DEGS waves are possible.

An interesting finding of our study is that 12.9% of our sample ever reported to have sought professional help due to mental health problems without meeting lifetime and 12 month criteria of a mental disorder as assessed in our study. This group represents a remarkable 31.6% of all users in our study. An evident potential reason for this finding might be that we did not cover all mental disorders listed in DSM‐IV‐TR and ICD‐10. For example, neurodevelopmental or neurodegenerative disorders, as well as personality or sleep disorders were not included, and the spectrum of substance, somatoform, dissociative and trauma/stress‐related disorders was restricted. Further, popular syndromes associated with helpseeking, like “burn‐out” (Hapke et al., 2013) were not included in DEGS1‐MH. This remarkable finding prompts future investigation, for example examining subthreshold conditions and linking these findings to information of the comprehensive health information from DEGS1.

There are two noteworthy unexpected results: First, we found that in big cities (>500,000 inhabitants) with an extensive and diverse range of mental health care institutions, the utilization rates were similar to those in rural areas. Secondly, psychotherapists were reported as the most frequent type of contact because of mental health reasons, exceeding even the primary care physicians and the psychiatrist. This finding contrasts not only our own previous results from the 1998 health survey, where primary care was found to be most frequent provider (Wittchen et al., 2001). It also seems to differ from findings derived from German routine administrative data (Gaebel et al., 2013), which highlighted the core role of the primary care and other somatic medical sectors. German health insurance data in persons with depression, analysed in that study showed that general practitioners and other somatic medical specialists were the most frequent providers of mental health care (Gaebel et al., 2012b). Comparisons of general population survey data with routine administrative data are generally difficult, due to substantially different methodologies of data collection and analysis. Routine data have their own limitations, e.g. health insurance data are mainly collected for reimbursement, not for epidemiological purposes. Thus, as mentioned above with regard to prevalence of any contact, one may only speculate about putative reasons for the discrepancy of findings on the most frequently used mental health services: persons may perceive and report services as “psychotherapist” services even though a routine data set may not include them, like psychological counseling. In addition, they often may not be able to distinguish between psychiatrists, medical and psychological psychotherapists. On the other hand, persons in routine medical care who are diagnosed and recorded with a mental disorder for administrative reasons may not even be aware of this. For international comparisons, the specific structures and regulations of the German health care and reimbursement system (e.g. mandatory coverage of all services, including psychological psychotherapists) might be co‐responsible for our findings that are further consistent with a European trend. Alonso et al. (2004) described in their European comparisons that mental health specialists are consulted more frequently for mental health disorders than the general practitioner. This finding seems distinctive for European countries given the predominant role of the general practitioner in other non‐European countries (Kessler et al., 2008).

Limitations

Our findings are not based on routinely recorded administrative statistics by providers or insurance companies, but rely exclusively on the subjects self‐report.

Due to reliance on self‐report our utilization data are subject to the respondent's perception, understanding of terms and recall error. The subject's answers to utilization questions might be erroneous in some cases (e.g. if respondents confused “psychologist” with “psychiatrist”) and the respondents designation of type of provider might not be in concordance with the true formal designation of an institution (e.g. clinic attached to a hospital might be misconceived by a respondent as general hospital).

Comparability with administrative statistics is limited because they rely on physician's routine diagnoses with questionable reliability and validity, subject to bias by reimbursement considerations and lack of expertise and competence.

Utilization rates are reported irrespective of type, frequency, and adequacy of treatment provided. Further steps to investigate type and frequency of treatments in various health care settings and to define minimal adequate treatment standards are needed.

Minor differences to previous surveys might be due to slightly different wording of core CIDI‐questions and different context in which these questions were provided. Our gateway question: “Have you ever contacted/visited any of the list (a list of 27 health care institutions and service providers) because of mental, psychosomatic, or substance use problems?”, was meant to enhance recognition of providers by use of the long respondent list. Other CIDI studies (e.g. ESEMeD and WMH Survey Initiative) used simpler question formats, without necessarily providing such a long list of providers.

This report presents data from the utilization section of the interview only. Information regarding service use as asked at the end of each specific diagnostic section of the CIDI‐interview has not been considered so far and will be dealt with in subsequent papers on specific disorders.

Kaplan‐Meier curves used to estimate the probability of service use in years since onset of disorders has limitations: First, the participant's capacity of recalling lifetime events accurately might be limited. Second, the actual cause of the reported service use due to mental health problems is unclear. It is not excluded that early subthreshold conditions or other comorbid mental disorders might have caused the service use. Third, participant's records of service use prior to the disorder onset were not considered in the Kaplan‐Meier curves.

Both, lifetime as well as 12‐month service use dates, cannot reliably inform about the effects of improvements in the health care system that have taken place in the last decade.

Conclusion

Despite considerable changes in the mental health field in Germany, a country offering access to a comprehensive mental health care system without major financial barriers, we find no indications of considerable better or substantially higher utilization rates for mental disorders as compared to European countries with a nationally comparable mental health care system (Wittchen et al., 2005; Wittchen et al., 2011). We also see – superficially examined – no indications of evidence of major changes as compared to our previous nationwide survey in 1998 (Wittchen et al., 2001; Jacobi et al., 2004). The question, whether these data signal a considerable degree of unmet needs cannot yet be answered. To address this question, further more detailed analyses of the data are needed to examine type, frequency, and adequacy of treatments of mental disorders. Furthermore, appropriately matched comparison with the DEGS1‐MH predecessor study GHS‐MHS from 1998 is needed to identify any changes in utilization patterns and to review the adequacy of interventions by type of disorder.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors do not report conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

DEGS1 and DEGS1‐MH are projects by the Robert Koch Institute (Berlin, Germany; head of the Department of Epidemiology and Health Monitoring: Dr Bärbel‐Maria Kurth) funded primarily by the German Ministry of Health (BMG). Supplementary funding is provided by the Technische Universität Dresden, and by the Stiftung Seelische Gesundheit inaugurated by the German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN) for implementation of the neurocognitive assessment and for extending the psychosis section (Prof. Dr Wolfgang Maier, Prof. Dr Wolfgang Gaebel). The authors would like to acknowledge the support of all Robert‐Koch‐Institut (RKI) staff in the fieldwork of the project, in particular Dr Heike Hölling, and the responsible RKI project officer for DEGS1‐MH, Michael Lange. The authors also thank the many staff members and interviewers of DEGS1‐MH at Technische Universität Dresden, in particular Lisa Beyer, Ariane Bürkner, Marlen Gehrke, Gerry Gwozdz, Esther Lochmann, Doreen Opitz, Stephanie Preiß, Kristina Schäfer, Lucie Scholl, Kathrin Spitzer, Yuliya Stankevich and Anke Vogel for their exceptional contributions during the field phase of DEGS1‐MH. Above all, the authors wish to thank all the DEGS1‐MH study participants.

Mack S., Jacobi F., Gerschler A., Strehle J., Höfler M., Busch M. A., Maske U. E., Hapke U., Seiffert I., Gaebel W., Zielasek J., Maier W. and Wittchen H.‐U. (2014), Self‐reported utilization of mental health services in the adult German population – evidence for unmet needs? Results of the DEGS1‐Mental Health Module (DEGS1‐MH), International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23, pages 289–303, doi: 10.1002/mpr.1438

References

- Alonso J., Angermeyer M.C., Bernert S., Bruffaerts R., Brugha T.S., Bryson H., de Girolamo G., de Graaf R., Demyttenaere K., Gasquet I., Haro J.M., Katz S.J., Kessler R.C., Kovess V., Lépine J.P., Ormel J., Polidori G., Russo L.J., Vilagut G., Almansa J., Arbabzadeh‐Bouchez S., Autonell J., Bernal M., Buist‐Bouwman M.A., Codony M., Domingo‐Salvany A., Ferrer M., Joo S.S., Martínez‐Alonso M., Matschinger H., Mazzi F., Morgan Z., Morosini P., Palacín C., Romera B., Taub N., Vollebergh W.A.M. (2004) Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(Suppl. 420), 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badura B., Ducki A., Schröder H., Klose J., Meyer M. (2013) Fehlzeiten‐Report 2013. Verdammt zum Erfolg – Die süchtige Arbeitsgesellschaft? Heidelberg, Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bellach B.M., Knopf H., Thefeld W. (1998) The German Health Survey 1997/98. Gesundheitswesen, 60(2), 59–68 (in German). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAK‐Gesundheit . (2013) Gesundheitsreport 2013. http://www.dak.de/dak/download/Gesundheitsreport_2013-1146388.pdf [8 October 2013].

- European Commission . (2005) Green Paper. Improving the Mental Health of the Population: Towards a Strategy on Mental Health for the European Union. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/mental/green_paper/mental_gp_en.pdf [20 July 2012].

- Gaebel W., Kowitz S., Fritze J., Zielasek J. (2013) Use of health care services by people with mental illness: secondary data from three statutory health insurers and the German statutory pension insurance scheme. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 110(47), 799–808, DOI 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W., Zielasek J. (2012a) Psychiatry in Germany 2012. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(4), 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W., Kowitz S., Zielasek J. (2012b) The DGPPN research project on mental healthcare utilization in Germany: inpatient and outpatient treatment of persons with depression by different disciplines. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 262(2), 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke U., Maske U.E., Scheidt‐Nave C., Bode L., Schlack R., Busch M.A. (2013) Chronic stress among adults in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 56, 749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F., Mack S., Gerschler A., Scholl L., Höfler M., Siegert J., Buerkner A., Preiß S., Spitzer K., Busch M., Gaebel W., Maier W., Wagner M., Zielasek J., Hapke U., Wittchen H.U. (2013) The design and methods of the Mental Health Module in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1‐MH). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 22(2), 83–99, DOI 10.1002/mpr.1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F., Höfler M., Siegert J., Mack S., Gerschler A., Scholl L., Busch M., Hapke U., Maske U., Gaebel W., Maier W., Wagner M., Zielasek J., Wittchen H.U. (2014) 12‐month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1‐MH). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, DOI 10.1002/mpr.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F., Wittchen H.‐U., Hölting C., Höfler M., Pfister H., Müller N., Lieb R. (2004) Prevalence, co‐morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS). Psychological Medicine, 34, 1–15, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291703001399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F., Wittchen H.‐U., Müller N., Hölting C., Sommer S., Lieb R., Höfler M., Pfister H. (2002) Estimating the prevalence of mental and somatic disorders in the community: aims and methods of the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 11(1), 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A.F. (1997) Mental health literacy: a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamtsiuris P., Lange M., Hoffmann R., Schaffrath Rosario A., Dahm S., Kurth B.‐M. (2013) Die erste Welle der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1): Stichprobendesign, Response, Gewichtung und Repräsentativität. Bundesgesundheitsbl, 56, 620–630, DOI: 10.1007/s00103-012-1650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) (2001) Grunddaten zur Vertragsärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland 2001. http://www.kbv.de/media/sp/Grunddaten_2001.pdf [8 October 2013].

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) (2011) Grunddaten zur vertragsärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschlang. http://www.kbv.de/media/sp/Grunddaten_2011.pdf [8 October 2013].

- Kessler R.C., Üstün T.B. (2004) The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Üstün T.B. (2008) The WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders, New York, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert T., Kroll L.E., Müters S., Stolzenberg H. (2013a) Measurement of socioeconomic status in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsbl, 56, 631–636, DOI: 10.1007/s00103-012-1663-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert T., Kroll L.E., von der Lippe E., Müters S., Stolzenberg H. (2013b) Socioeconomic status and health. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsbl, 56, 814–821, DOI: 10.1007/s00103-013-1695-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner G., Wittchen H.‐U., Perkonigg A., Holly A., Schuster P., Wunderlich U., Türk D., Garczynski E., Pfister H (1998) Structure, content and reliability of the Munich‐Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M‐CIDI). Substance use sections. European Addiction Research, 4, 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattay P., Butschalowsky H., Rommel A., Prütz F., Jordan S., Nowossadeck E., Domanska O., Kamtsiruis P. (2013) Utilization of outpatient and inpatient health services in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsbl, 56, 832–844, DOI 10.1007/s00103-013-1665-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed V., Gander F., Pfister H., Steiger A., Sonntag H., Trenkwalder C., Hundt W., Wittchen H.‐U. (1998) To what degree the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) correctly identifies DSM‐IV disorders? Testing validity issues in a clinical sample. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Robert‐Koch‐Institut (Ed.) (2002) The German National Health Interview and Examination Survey 1998 – the basis for health surveillance in German [German version only]. Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. http://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Health_Monitoring/Health_Reporting/GBEDownloadsB/baustein_der_gesundheitssurveillance.html [31 January 2013].

- Royall R.M. (1986) Model robust confidence intervals using maximum likelihood estimators. International Statistical Review, 54, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt‐Nave C., Kamtiuris P., Goesswald H., et al. (2012) German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS) – design, objectives and implementation of the first data collection wave. BMC Public Health, 12, 730, DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TK (Techniker Krankenkasse) (2013) Gesundheitsreport. Berufstätigkeit, Ausbildung und Gesundheit. Band 28. http://www.tk.de/centaurus/servlet/contentblob/516416/Datei/83065/Gesundheitsreport-2013.pdf [8 October 2013].

- Vos T., Flaxman A.D., Naghavi M., et al. (2013) Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 380, 2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.S., Lane M., Olfson M., Pincus H.A., Wells M.D., Kessler R.C. (2005) Twelve‐month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiary, 62, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Jacobi F. (2001) Die Versorgungssituation psychischer Störungen in Deutschland. Eine klinisch‐epidemiologische Abschätzung anhand des Bundes‐Gesundheitssurveys 1998. Bundesgesundheitsblatt ‐ Gesundheitsforschung ‐ Gesundheitsschutz, 44(10), 993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U. (1994) Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 57–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Höfler M., Gander F., Pfister H., Storz S., Üstün T.B., Müller N., Kessler R.C. (1999) Screening for mental disorders: performance of the Composite International Diagnostic‐Screener (CID‐S). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 8(2), 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Jacobi F. (2005) Size and burden of mental disorder in Europe: A critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(4), 357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Jacobi F., Rehm J., Gustavsson A., Svensson M., Jönsson B., Olesen J., Allgulander C., Alonso J., Faravelli C., Fratiglioni L., Jennum P, Lieb R, Maercker A., van Os J., Preisig M., Salvador‐Carulla L., Simon R., Steinhausen H.‐C. (2011) The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21, 655–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Pfister H. (1997) DIA‐X‐Interviews: Manual für Screening‐Verfahren und Interview; Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA‐X‐Lifetime); Ergänzungsheft (DIA‐X‐Lifetime);Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA‐X‐12 Monate); Ergänzungsheft (DIA‐X‐12Monate); PC‐Programm zur Durchführung des Interviews (Längs‐ und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm, Frankfurt, Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.‐U., Robins L.N., Cottler L., Sartorius N., Burke J., Regier D. (1991) Cross‐cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) – results of the multicenter WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials (wave I). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2011) World Report on Disability, Geneva, WHO Press. [Google Scholar]