Abstract

The German federal states initiated the “Pathological Gambling and Epidemiology” (PAGE) program to evaluate the public health relevance of pathological gambling. The aim of PAGE was to estimate the prevalence of pathological gambling and cover the heterogenic presentation in the population with respect to comorbid substance use and mental disorders, risk and protective factors, course aspects, treatment utilization, triggering and maintenance factors of remission, and biological markers. This paper describes the methodological details of the study and reports basic prevalence data. Two sampling frames (landline and mobile telephone numbers) were used to generate a random sample from the general population consisting of 15,023 individuals (ages 14 to 64) completing a telephone interview. Additionally, high‐risk populations have been approached in gambling locations, via media announcements, outpatient addiction services, debt counselors, probation assistants, self‐help groups and specialized inpatient treatment facilities. The assessment included two steps: (1) a diagnostic interview comprising the gambling section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for case finding; (2) an in‐depth clinical interview with participants reporting gambling problems. The in‐depth clinical interview was completed by 594 participants, who were recruited from the general or high‐risk populations. The program provides a rich epidemiological database which is available as a scientific use file. Copyright © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: pathological gambling, problem gambling, behavioral addiction, mental disorder, psychiatric epidemiology

Background

Pathological gambling is defined in the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) as a persistent and recurrent maladaptive pattern of gambling that disrupts personal, family, or vocational pursuits (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In the most recently published fifth edition of DSM, the diagnosis was termed gambling disorder and moved from the chapter “Impulse Control Disorders” to “Substance‐Related and Addictive Disorders” as the sole condition in a new category on behavioral addictions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Additionally, a spectrum of gambling problems encompassing milder forms has been proposed, which are frequently termed problem gambling or at‐risk gambling (Shaffer and Kidman, 2004). However, problem gambling is less consistently defined across studies and not yet included in major diagnostic systems.

The growth of the gambling market in recent decades in many nations has evoked an interest in evaluating and monitoring the public health relevance of pathological and problem gambling (Korn and Shaffer, 1999; Shaffer and Kidman, 2004). Negative consequences to individuals with pathological gambling have been described in the areas of financial problems, family dysfunction and violence, criminal conduct, substance use and mental disorders, and suicide (Korn and Shaffer, 1999; Shaffer and Kidman, 2004). However, up to now, scientific evidence from population‐based studies has primarily focused on prevalence data and notable inconsistencies have been found. A recent review including 33 studies published between 2000 and 2005 reported prevalence data of pathological gambling among adults ranging from 0.15% to 3.5% (Stucki and Rihs‐Middel, 2007). Another review covering publications from 2000 to 2010 identified 39 non‐clinical national studies reporting current prevalence data of pathological and problematic gambling (Sassen et al., 2011a). Estimates of the past‐year prevalence of pathological gambling ranged from 0.02% to 2.0% among the total adult populations, 0.4% to 26.0% among adolescents, 0.8% to 6.0% among college students and 1.2% among populations aged 60 years or older. A more comprehensive report based on 202 published and unpublished prevalence studies in adult populations identified several methodological factors impacting on prevalence estimates (Williams et al., 2012). In summary, the earlier mentioned authors discuss the following aspects, that may account for inconsistent findings: First, different assessment instruments and diagnostic thresholds for case definition have been used. Second, exclusion criteria as part of the diagnostic procedure differ. For example, a certain frequency of gambling or amount of money spent on gambling was used as a skip rule to exclude subjects from being assessed for gambling problems. Third, different reference timeframes and criteria for the clustering of symptoms within specific time intervals have been used for prevalence estimates. Fourth, sampling bias includes undercoverage of institutionalized subjects in telephone surveys and exclusion of subjects who have no telephone. Fifth, selection bias includes differences in the probability of participation in a survey in specific subgroups of the population, e.g. defined by socio‐economic characteristics. Sixth, sample weights did not include adjustments for social indicators and thus did not compensate for a related selection bias. Seventh, the description of the survey to potential participants prior to their decision to participate may account for selection bias (e.g. “gambling survey”, “survey on leisure time activity” or “survey on mental health problems”). Finally, modes of administration such as postal, online, phone or face‐to‐face interviews may play a role in reporting bias. In addition to these methodological issues, secular trends and national differences may have contributed to inconsistencies among studies (Williams et al., 2012).

In Germany seven general population based surveys have been conducted since 2006 providing past year prevalence estimates of pathological gambling, which were in the lower range compared to the aforementioned studies from other nations. Methodological details of those surveys are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of recent German general population surveys

| Source | Year of data collection | Case finding instrument | Funding | Survey mode /sampling frame | Age range in years | Sample size | Threshold for the assessment of gambling problems | Past year prevalence estimate of pathological gambling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buth and Stöver (2008) | 2006 | DSM‐IV | Gambling provider | Phone/RDD and online access panel | 18 – 65 | 7,981 | Weekly gambling or spending ≥ 50 €/month on some form of gambling | 0.56% |

| Bühringer et al. (2007) | 2006 | DSM‐IV | Public | Paper‐pencil and phone and/official inhabitants registries | 18 – 64 | 7,817 | Spending ≥ 50 €/month on some form of gambling | 0.20% |

| Haß et al. (2012) | 2007 | SOGS | Gambling provider | Phone/RDD | 16 – 65 | 10,001 | Any gambling past year | 0.19% |

| Haß et al. (2012) | 2009 | SOGS | Gambling provider | Phone/RDD | 16 – 65 | 10,000 | Any gambling past year | 0.45% |

| Sassen et al. (2011b) | 2009 | DSM‐IV | Public | Paper‐pencil, online and phone /official inhabitants registries | 18 – 64 | 8,006 | Spending ≥ 50 €/month on some form of gambling | 0.31% |

| TNS EMNID (2011) | 2011 | DSM‐IV | Gambling machine industry | Phone/RDD | >18 | 15,002 | Spending ≥ 50 €/month for gambling | 0.23% |

| Haß et al. (2012) | 2011 | SOGS | Gambling provider | Phone/RDD | 16 – 65 | 10,002 | Any gambling past year | 0.49% |

So far no epidemiological data from German samples is available assessing lifetime gambling problems in a broader context of psychiatric conditions and related factors. By focusing on past year disorders previous surveys did not provide information related to course aspects. Furthermore, despite being large‐scale surveys, the number of identified cases in those studies ranged from only 14 to a maximum of 45 individuals. Even the largest population‐based study to date (US American NESARC, N = 43,093 including 185 cases with a lifetime history of pathological gambling) identified only eight individuals with current and four with former pathological gambling disorder seeking professional help (Slutske, 2006). Thus, for feasibility reasons general population‐based sampling designs may not be sufficient to reach sample sizes that allow analyzing more complex research questions related to relevant correlates of pathological gambling.

To improve the available epidemiological evidence, the German federal states funded the Pathological Gambling and Epidemiology (PAGE) program. In detail, the aim of the PAGE program was: (1) to estimate prevalence rates of current and lifetime diagnoses of pathological gambling including sub‐threshold categories for the German population aged 14 to 64; (2) to investigate factors related to gambling problems, e.g. (comorbid) substance use and mental disorders (including personality disorders), dimensional measures of psychopathology, psychosocial resources and biological markers (from saliva samples); (3) to analyze course aspects, treatment utilization, and triggering and maintenance factors of remission. PAGE was intended to describe the heterogenic presentation of the disorder in the population by using a variety of parallel recruitment strategies with access to the general and high‐risk populations. These strategies should ensure a sufficient number of cases and a broad range of assessment instruments to allow for a comprehensive characterization of individuals with pathological gambling across all samples. This set of available characteristics allows for comprehensive phenotyping and profound dimensional and categorical analyses of gambling problems in a relatively large sample. In this paper, we present an outline of the study protocol, results of the fieldwork and basic prevalence data.

Methods

The fieldwork of the PAGE program was conducted between January 2010 and March 2011 and has been approved by the ethical review boards of the Universities of Greifswald and Lübeck (Reg.‐No. BB 95/09; Reg.‐No.10‐068). The project was conducted in cooperation with the Institute for Applied Social Science (“infas – Institut für angewandte Sozialwissenschaft”), which organized parts of the fieldwork and provided methodological support. The study followed a cross‐sectional design including a variety of recruitment channels. Participants from the general population were recruited via a nationwide telephone sample. High‐risk participants were recruited at gambling locations, among patients undergoing specialized inpatient treatment for pathological gambling and via a project telephone hotline, which was available for volunteers responding to media announcements or requests of outpatient addiction counseling services, debt counselors, probation assistants, and self‐help groups. The reason for the additional recruitment of these high‐risk samples (not used for prevalence estimation) was to include a higher number of pathological gamblers than could have been expected from the general population samples alone and to include subpopulations with pathological gambling disorder that might not have been covered by a single recruitment channel approach.

Furthermore, the study design included a two‐step procedure consisting of (1) an initial diagnostic interview focusing on gambling behavior as well as the assessment of pathological gambling criteria and (2) a comprehensive, in‐depth clinical interview among those reporting gambling problems in the diagnostic interview. All participants were informed that study participation was voluntary and consent could be withdrawn at any time. Oral consent to participate and to store contact data was obtained during the telephone interviews. An informed consent form was signed by all participants during the clinical interview and by parents of minors. The consent to store contact data for follow‐up contacts was obtained by a second signature. A separate written information and consent procedure was used for the collection of a saliva sample that was intended for genotyping and gathered at the end of the in‐depth clinical interview.

General population telephone samples

Previous research has suggested that a substantial part of subjects suffering from pathological gambling did not have landline telephones. These studies revealed a high prevalence of problem gambling among attendees of soup kitchens and homeless shelters, exceeding estimates based on telephone surveys (Lepage et al., 2000). One study investigating a sample of individuals who rely on community assistance for their survival revealed that, among those meeting criteria for pathological gambling, 46% did not have a telephone (Lepage et al., 2000). In recent years, the increase of households accessible via cell phones but not landline phones (“mobile‐only's”) has become significant (Glemser, 2007). Therefore, the dramatically increasing spread of cell‐phones including disadvantaged populations has provided a new option for improving the limited coverage of the general population landline telephone surveys. In 2006, the Federal Network Agency reported that the number of cell phones in Germany exceeded the number of inhabitants, and a mobile phone penetration rate of 100% was assumed (Glemser, 2007). Therefore, two sampling frames were used for the general population sample of the present study, i.e. a landline telephone‐ and a mobile telephone‐number sample.

Landline telephone sample

We used a stratified and clustered sampling design. In the first of three stages, we sampled 53 German communities (primary sampling unit) using a “probability proportional to size” procedure (Levy and Lemeshow, 2008), which was based on the official statistics regarding the number of inhabitants aged 14 and older (reference date: January 2008). The number of communities was kept at a moderate level to facilitate coverage of all areas for face‐to‐face interviews in a subset of participants suffering from gambling problems. Implicit stratification by geographic region and density of electronic gambling machines was used to ensure a representative selection of communities. Density of electronic gambling machines was used as an indicator quantifying the regionally available gambling opportunities which might in turn influence gambling related problems. Density of electronic gambling machines was computed based on five surveys conducted from 1998 to 2008 including 1670 communities (response rate in 2008: 99.3%; Trümper and Heinemann, 2008). The data covered virtually all German communities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and a selection of smaller communities in one federal state (percentage of total German population covered in the included communities in 2008: 73%). In Germany, gambling establishments and/or electronic gambling machines have to be registered for regulatory and tax administration purposes. For the stratification of communities, we used the number of electronic gambling machines in gambling establishments per 10,000 inhabitants averaged across the five surveys and grouped in quintiles. Missing data in communities with less than 10,000 inhabitants were imputed by available data of the surrounding county.

At the second stage, a fixed number of landline telephone numbers (secondary sampling unit) was generated for each selected community following the Gabler–Häder sampling design (Häder and Gabler, 1998), which is a random digit dialing procedure adapted to the specifics of the German telephone number allocation practice. The procedure allows for representative inclusion of numbers listed and not listed in accessible telephone registries with acceptable efficiency. Because landline telephone numbers represent households that might comprise several target persons (third sampling unit), a quasi‐random selection was achieved by the “last‐birthday‐question” method. The planned sample size for the diagnostic interview was 14,000 participants.

Mobile‐only sample

Recent estimates for Germany suggest that approximately 12% of the total population is reachable via cell phone but not landline telephone (European Commission, 2011). Mobile‐only access was more prevalent among single households and younger people. At the time of data collection, the prevalence of mobile‐only access was estimated at 14% for the population aged 14 to 64 years (analyses based on unpublished survey data provided by the Institute for Applied Social Science, infas). Corresponding to the procedure described for the sampling of landline numbers, an adapted random digit dialing procedure was used to generate mobile phone numbers comprising a representative portion of telephone numbers, which were listed or not listed in accessible registries. To identify potential participants, we followed a screening approach according to which individuals with sufficient German language capacities, reporting mobile‐only status and matching the age range were eligible for the interview. This sample was considered as a nationwide one‐stage sample because a mobile phone number could not be assigned to a geographic region and it was assumed that, in general, a mobile phone is used by one person only. The planned sample size for the diagnostic interview was 1000 participants.

Samples from populations with a high risk of gambling problems

Sample of gambling location attendees

To generate a sample of gambling location attendees, we compiled a list of all gambling establishments and casinos registered in the same communities selected for the landline telephone survey. In Germany gambling establishments are specialized places primarily offering gambling with electronic gambling machines. Casinos are commonly larger places underlying different legal regulations and typically additionally offering table games. Entrance of minors was prohibited by law in gambling establishments and casinos. The final list included 431 gambling locations. An initial postal request to the management of the gambling establishments regarding permission to contact gamblers in the locations yielded no response. After negotiations, the umbrella organizations of the companies provided a reference letter in which the participation in our study was recommended. In response to a second mailing, which included the reference letter, 24 companies permitted interviewers to ask gamblers in their gambling establishments or casinos to participate in the study. In addition, not responding companies were contacted by telephone, and permission was provided by an additional 14 gambling establishments and one casino. In general, permission was given to address gamblers in the entrance or bar area but not during gambling. Initial interviewer experience revealed that addressing individuals during gambling (if allowed by the company) was not feasible because they usually did not tolerate any interruption. The interviewers were instructed to ask every attendee for study participation. However, a systematic coverage of all attendees was not feasable, if the establishment was highly frequented. Together, the interviewers were present in 39 gambling locations covering a total time period of 534 hours. Gamblers were informed about the study purpose, received a leaflet with details regarding study participation and asked to provide contact data for a telephone interview, which was planned during the next few days. During the initial part of the recruitment period, an incentive of 10 Euro was promised, which was to be paid after the telephone interview. To improve participation rates, the incentive was increased to 20 Euro (received by 63.4% of the final sample) later on. A sample size of 1000 gambling location attendees with a complete telephone interview was planned.

Sample of patients in specialized inpatient treatment facilities for pathological gambling

We conducted a search for facilities providing specialized treatment of pathological gambling via Internet, inquiry at professional associations and experts. After an initial contact, 10 out of 27 identified facilities were excluded for the following reasons: (1) service was restricted to outpatient treatment; (2) the facility was currently not available due to changes regarding the treatment concept; (3) no regular provision of specialized treatment for pathological gambling due to low demand; (4) participation in another research project. The responsible therapists working in the remaining clinics were asked to introduce the study to their patients and schedule an appointment for the clinical interview at the facility. Clinics and patients were assigned to the interview based on the promptness of response and requirements of the project logistics until the planned sample size of 50 patients was reached. In total, eight clinics provided patients included in the study (provided patients per clinic: minimum one; maximum 14; median 6.5).

Sample of volunteers contacting the project hotline

People currently suffering from gambling problems or who had overcome former gambling problems were asked to call a free hotline, which was announced by several media reports in response to two press agency messages and a leaflet. The leaflet was distributed via self‐help groups for pathological gambling, outpatient addiction counseling services, debt counselors and probation assistants.

To recruit self‐help group members, we informed delegates of a meeting for self‐help group leaders about the study and asked for recommendation of the study to their groups and distribution of the leaflet. In addition, contacts to self‐help groups were established via specialized departments for pathological gambling in the federal states.

For recruitment via outpatient addiction counseling services, we conducted a search of a nationwide registry of counseling facilities. In total, 493 services located in the communities selected for the landline telephone survey had been identified and were contacted via a postal mail requesting distribution of the leaflet among their clients. To support these measures, further contacts had been established with specialized departments at the federal level.

Finally, mail was sent to 230 debt counselors registered in the communities that had been selected for the landline telephone survey to ask for assistance in recruiting clients with gambling problems and distribution of the leaflet. Contact data was researched online. Further contact with selected debt counseling organizations was made by telephone. Supporting measures included contact and information from respective umbrella organizations. The same approach was followed with respect to probation assistants, including a systematic mailing to 83 facilities and contacts with superior administrative departments. It was planned to include as many volunteers as necessary to reach a sample size of 570 participants in the in‐depth clinical interview taking all recruitment channels together.

Assessment

The assessment consisted of an initial diagnostic interview and an in‐depth clinical interview that was supplemented by a paper‐pencil questionnaire. All interviews were computer assisted. In general, the diagnostic interview was administered via telephone while the clinical interview was conducted face‐to‐face at participants' homes (35.4% of all interviews) or at another suitable location (e.g. hotel lobby, restaurant, rooms provided by universities or local addiction counseling services). Aside from this, a combination of the diagnostic and in‐depth clinical interview was administered at one occasion face‐to‐face with all participants recruited via specialized inpatient treatment facilities. The same was done occasionally if volunteers provided initial information strongly suggesting that gambling problems have been present to an extent that qualified for the clinical interview. Although recent meta‐analysis revealed evidence of bias for mixed modes of questionnaire administration, the face‐to‐face and telephone mode are considered to be equivalent in case of a moderate interview length and closed question format (Bowling, 2005). More specific studies in the field of psychiatric epidemiology found that telephone administration of standardized and structured interviews revealed highly concordant diagnostic decisions compared to face‐to‐face interviews (Aneshensel et al., 1982; Kessler et al., 2009; Sobin et al., 1993).

Diagnostic interview

The case‐finding instrument was based on the gambling section of the World Mental Health (WMH) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 3.0 published by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2009). The assessment of gambling participation was adapted to the kinds of gambling available in Germany and extended to cover lifetime and past year gambling separately for 21 categories. In addition to conventional kinds of gambling such as casino games, electronic gambling machines, lotteries, poker and sport betting, the kinds of gambling also included high‐risk trading on the stock exchange, gambling on television quiz channels, privately organized or illegal gambling and “Fun Games”. The latter are electronic gambling machines that are operated with tokens instead of money and thus are not considered as gambling for money. However, informal reports of treatment experts suggest that, although prohibited by law, tokens might have been changed back to money in some gambling establishments.

The items assessing gambling behavior in the original gambling section of the CIDI asked for “times gambled” for a specific game. In contrast, we assessed the frequency of gambling in days (“How many days in your life/in the last 12 months did you spend money for …”). In addition, we assessed the predominant access path, e.g. Internet, postal, telephone, or location of gambling, e.g. gambling establishment or casino, for each gambling category endorsed during participants' lifetime. Moreover, we change the skip rule steering the omission or presentation of items assessing gambling problems in the original gambling section of the CIDI. In the original version the items were omitted if the interviewees reported gambling for money no more than 10 times in life or if the maximum of losses due to gambling within any previous year (taking all wins and losses together) did not exceeded 364 US$. This skip rule was enabled in our study. For the general population sample, an interim analysis was planned a priori to test the sensitivity of different alternative skip rules based on the first 1000 interviews. To allow analyses testing the convergence of the pathological gambling and substance use criteria we included additional symptom questions (Denis et al., 2012). The questions were taken from the Nicotine, Alcohol and Drug sections of the CIDI and adapted to gambling behavior. In total, we assessed 27 gambling problems. Finally, we computed the number of symptoms defined by Criterion A for pathological gambling according to DSM‐IV based on the 16 questions of the original CIDI gambling section. Participants' gambling was categorized by the number of symptoms for pathological gambling according to DSM‐IV Criterion A separating two sub‐threshold categories of gambling problems defined by 1–2 and 3–4 symptoms, and pathological gambling (5–10 symptoms).

To avoid systematic dropout during the recruitment of the general population telephone sample, the study was described as a survey about leisure time activities such as social activities, Internet use and gambling. Accordingly, the interview started with items covering participation in 13 social activities (e.g. sport events, cinema, church attendance, club meetings) and social trust (Hanson et al., 1997), followed by items assessing Internet use and related problems, gambling participation and related problems, and socio‐economic variables. For all the other samples, the diagnostic interview was reduced to the case‐finding instrument if conducted by telephone and the remaining aforementioned items were assessed face‐to‐face along with the in‐depth clinical interview.

In‐depth clinical interview

Participants that fulfilled at least one symptom from the DSM‐IV Criterion A for pathological gambling (lifetime) according to the diagnostic interview were eligible for the in‐depth clinical interview. The instruments included in the clinical interview were configured to match different groups of participants defined by age (adolescents versus adults) and recency of gambling problems (gambling problems occurring within the last 12 months versus more than 12 months ago). The total item pool comprised 2194 items (cf. Table 2). The length of the individual assessment was reduced by various skip rules particularly embedded in the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M‐CIDI; Wittchen et al., 1995; Wittchen and Pfister, 1997), which contributed the largest share of the item pool. In addition, some instruments were administered via a paper‐pencil questionnaire (two versions for participants with current and former gambling problems: 27/16 pages sized A4), which were to be filled in after the face‐to‐face interview and sent back via a free mail envelope. Finally, at the end of the clinical interview, participants were asked to provide a saliva sample for genotyping.

Table 2.

Instruments included in the diagnostic or in‐depth clinical interview

| Number of items | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio‐economic characteristics | ||

| Basic socio‐demographics | 21 | Adapted from (Hoffmeyer‐Zlotnik et al., 2010) |

| Extended socio‐demographics/financial situationa | 37 | Adapted from (Hoffmeyer‐Zlotnik et al., 2010)/— |

| Diagnostic of pathological gambling, gambling behavior and gambling‐related problems | ||

| Lifetime and past‐month gambling participation by forms of gambling and access channels | 57 | — |

| WHO‐WMH CIDI 3.0 Gambling section (gambling participation items excl.) | 33 | (WHO, 2009) |

| Substance disorder symptom questions adapted from the M‐CIDI to gambling | 12 | (Wittchen et al., 1995; Lachner et al., 1998) |

| Screening for manic episode and gambling | 3 | Adapted from (Wittchen et al., 1995) |

| Screening for problem gambling | 2 | (Cunningham et al., 2009) |

| Lie – Bet questionnairea, b | 2 | (Johnson et al., 1998) |

| Gambling participation (frequency of gambling days and gambling hours per day last year and episode of highest participation in life)a | 8 | — |

| ACG – Adverse Consequences from Gamblinga | 12 | Adapted from (Moos et al., 1985) |

| PRISM – Gambling Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measurea | n.a. | Adapted from (Rumpf et al., 2004) |

| Familial gambling problems (Item 3 from South Oaks Gambling Screen)a, c | 1 | Adapted from (Lesieur and Blume, 1987) |

| Substance use and mental disorders | ||

| M‐CIDI core lifetime version of the sections: Nicotine, Anxiety (excl. specific phobia items), Depression, Mania, Alcohol, Drugs, Post‐traumatic Stress Disorder, Treatment Utilizationa | 1326 | (Wittchen et al., 1995; Wittchen and Pfister, 1997) |

| SKID II with skip rules omitted and exclusion of passive‐aggressive and depressive personality disorder itemsa, d | 98 | (Fydrich et al., 1997) |

| SDQ – Strength and Difficulty Questionnairea, e | 25 | (Klasen et al., 2003) |

| FDS – Questionnaire on Dissociative Symptomsa, c | 8 | (Spitzer et al., 2006) |

| RSQ‐10D – Rumination Scalea, c | 10 | (Huffziger and Kühner, 2012) |

| CAARS‐S – Connor Adult ADHD Rating Scale self‐rating short forma, c | 26 | (Christiansen et al., 2011) |

| CIUS – Compulsive Internet Use Scale | 18 | (Meerkerk et al., 2009) |

| IAT – Young's Internet Addiction Testa | 20 | (Widyanto and Mcmurran, 2004) |

| Risk and protective factors | ||

| BIS‐10/11 – Barrat Impulsiveness Scalea, c | 34 | (Preuss et al., 2003) |

| Delay and Probability Discountinga, c | 57 | (Madden et al., 2009) |

| Risk Propensity Scalea, c | 7 | (Nicholson, 2005) |

| GBQ – Gamblers Belief Questionnairea, c | 21 | (Steenbergh et al., 2002) |

| Social capital | 14 | (Hanson et al., 1997) |

| SSD – Scale for gambling related social pressurea | 30 | Adapted from (Bischof et al., 2003b) |

| SSA – Social Support Appraisal scalea | 28/56f | (Vaux et al., 1986) |

| Awareness of own gambling problems in the social environmenta | 10/20 f | — |

| Motivation to change gambling behavior | ||

| Self‐efficacy and readiness rulera, c | 2 | — |

| Readiness rulera, c | 1 | Adapted from (Heather et al., 2008) |

| CAR – Cognitive and Affect related assessment of Readinessa, b | 16 | — |

| GBDS – Gambling Decisional Balance Scalea, c | 26 | Adapted from (Hannöver et al., 2001) |

| Gambling treatment utilization | ||

| Utilization of different forms of help for gambling problemsa | 69 | ‐ |

| RFNSH – Reasons For Not Seeking Helpa | 12 | Adapted from (Hingson et al., 1982; Sobell et al., 1993) |

| Factors triggering and maintaining remission | ||

| Course of gambling problems, time and duration of remissiona, g | 8 | — |

| Subjective reasons for remissiona, g | 10 | — |

| SLD – Satisfaction with Life Domainsa | 8/16 f | (Dlugosch and Krieger, 1995) |

| CBI‐G – Coping Behaviors Inventorya, g | 36 | Adapted from (Bischof et al., 2003a) |

| GASS – Gambling Abstinence Self‐Efficacy Scalea, b, c | 24 | (Hodgins and El‐Guebaly, 2000) |

| SLR – Subjectively relevant Life domains for maintenance of Remissiona, c, g | 12 | — |

| Further assessments | ||

| Self‐rated general healtha | 1 | (Idler and Benyamini, 1997) |

| Binge drinking in last 12 monthsa | 1 | — |

| Medication with dopamine agonista | 4 | — |

| Time to first cigarettea | 1 | (Heatherton et al., 1991) |

| Saliva sample for genotypinga, d | n.a. | |

In‐depth clinical interview only.

Participants with current gambling problems only.

Administered as paper‐pencil questionnaire.

Adults only.

Adolescents only.

Assessed twice for participants with former gambling problems, referring to the two years preceding remission and the year following remission; for participants with recent gambling problems assessed once for the last year.

Participants with former gambling problems only.

developed within the present project or in previous projects of the research group and not yet published.

n.a. not applicable.

All instruments not available in German were translated by a psychologist and translated back to English by another psychologist. In case of discrepancies with the original version, the German version was corrected. For validation of the translation of the case‐finding instrument a specialized translation service was commissioned.

Study procedure and quality assurance

In the planning phase, we invited an external expert committee covering a broad range of relevant clinical and scientific expertise to ensure a high scientific quality standard for project administration. After an informational meeting of the committee, an advisory board consisting of seven experts was established to monitor the on‐going project and to provide feedback via telephone conferences and bilateral contacts.

The diagnostic telephone interviews were conducted by the cooperating survey research institute (infas) with established quality assurance measures. These included the programming of the survey software, contact procedures to maximize response rates, interviewer training and monitoring. The interview was pre‐tested and continuously checked for consistency during the fieldwork. The institute gained full access to all data relevant to the evaluation. In total, 612 interviewers were trained and employed in the landline telephone survey. Among them, 547 interviewers conducted one or more interviews, and 26 interviews were conducted on average (standard deviation [SD] = 35.97) between June 7 and October 22, 2010. For the mobile‐only survey, 385 trained interviewers were appointed. In total, 256 completed one or more interviews, and four interviews were conducted on average (SD = 4.02) between November 22, 2010 and February 1, 2011. The diagnostic telephone interview of gambling location attendees providing contact data (field period October 1, 2010–January 30, 2011) and persons contacting the project hotline (field period July 2, 2010–December 16, 2010) was conducted by 35 and 18 trained interviewers, respectively.

The in‐depth clinical interview was conducted by eight academics with experience in psychological diagnosis (seven interviewers held a degree in psychology equivalent to a master's degree and one was qualified by several years of experience in prior research projects). The interviewers participated in the development of the interview and were trained in several meetings. Additionally, they were trained by external experts in the application of the M‐CIDI and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Personality Disorders (SKID‐II; Fydrich et al., 1997) within two sessions lasting two and four days.

To ensure consistent fieldwork across the complex sampling design, data safety and protection, we adapted study‐management software developed at our institute. Each contact attempt and all data were registered and continuously synchronized between central and local databases installed on interviewers' notebooks and the databases delivered by the survey research institute, as well as the entry of the questionnaire data. The central database was used to monitor and administer the on‐going fieldwork, including optimized coordination of the interviewers traveling to the sampling points. All paper‐pencil questionnaires were entered in the central database twice, checked for consistency and corrected if necessary. Furthermore, the correct application of skip rules, avoidance of items missing due to omission and real‐time checks for inconsistent data were achieved due to the computerized administration of the interviews.

An incentive of 100€ was available to increase participation rates for the in‐depth clinical interview. To avoid aggravation of gambling problems or relapse, potentially negative consequences of cash payment or alternative options were explicitly discussed with the participants and, in case of recruitment in inpatient clinics, with the therapeutic team. An additional incentive of 10€ was offered for the provision of the saliva sample.

Results

General population surveys

Recruitment and participation

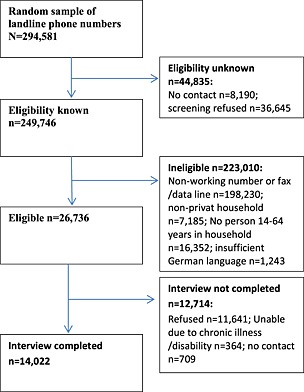

Figure 1 details the results of the recruitment procedure for the landline telephone survey. Eligibility was unknown for 15.2% of the telephone numbers primarily due to household refusal to provide the screening information. Ineligibility was confirmed for 84.8% of the telephone numbers. The major reason for ineligibility (88.9%) was owing to random generation of the telephone numbers being invalid, followed by no household member in the age range (7.3%), non‐private number (3.2%), and insufficient German language skills of the contact person (0.6%). Among the remaining 10.7% eligible numbers representing target persons within the specified age‐range 14,022 participants completed the interview. The main reason for non‐participation was refusal (91.6%), followed by not reached (5.6%) and inability to take part due to disease or cognitive impairment (2.9%). Based on the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) standard, we calculated a response rate of 44.5% (formula RR3; The American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2011). The calculation of RR3 was based on the assumption that “e” , i.e. the proportion of eligible units among the cases with known eligibility, was the same among the cases with unknown eligibility (here e = 0.107; Smith, 2009). According to the CASRO definition (formula COOP3; The American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2011) the cooperation rate is calculated based on the individuals who could be personally reached, i.e. those completing or refusing participation. Accordingly, the cooperation rate in the landline survey was 54.6% (14,022/26,736; cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing the sampling of the landline telephone survey.

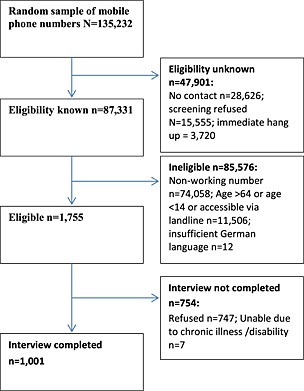

Figure 2 describes the results of the recruitment procedure for the mobile phone survey. Eligibility was unknown for 35.4% of the numbers because of no contact (59.8%), refusal to provide screening information (32.5%) or immediate hanging up (7.7%). Ineligibility was confirmed for 63.3% of the telephone numbers with the majority being non‐working numbers (86.5%) followed by not fulfilling the age or mobile‐only inclusion criterion (13.4%) or insufficient German language skills (0.01%). Among the eligible persons 1001 completed the interview. The main reason for non‐participation was refusal (99.1%) followed by inability to take part due to disease or cognitive impairment (0.9%). Based on an eligibility proportion among the cases with known eligibility of e = 0.020, the response rate (RR3) was 36.8%. The cooperation rate (COOP3) was 57.3%.

Figure 2.

Flow chart detailing the sampling of the mobile‐only telephone survey.

According to the electronic registration, the mean duration of the landline telephone interviews were 14.8 (SD = 6.8) and 18.4 (SD = 8.3) minutes including or excluding the abovementioned skip rule, respectively. The mean duration of the mobile‐phone interview was 18.4 minutes (SD = 8.3).

Sample weights

To account for different probabilities of inclusion resulting from the sampling design and non‐response, we developed weights for the landline and mobile‐only telephone samples. Separate weights were constructed for each sample, and then final weights for the combined analysis of both samples were calculated.

The design weights for the landline sample were defined as the inverted product of the inclusion probabilities of each sampling stage, i.e. the community, the household (represented by landline phone numbers) and the target person selection. In accordance with the sampling procedure, the stratification of the communities was considered for the computation of the inclusion probabilities. On the household and person level, the inclusion probability was determined by the number of telephone numbers assigned to each household and the number of target persons living in respective households. This information was gathered during the telephone interviews. The design weight was adjusted to the number of cases in the sample and trimmed at the 2.5 and 97.5 percentile (range: 0.125 to 20.689; 2.5‐percentile = 0.25; 95‐percentile = 2.93). Finally, an iterative proportional fitting algorithm was used to calibrate the design‐weighted distribution of socio‐economic variables to data of the German population derived from official statistics. The following variables were considered: age, sex, federal state, size of household, education level (graduation level), unemployment, and migration experience.

Analogous to the procedure described earlier, we constructed the design weights for the mobile‐only phone sample. Since we assumed that, in general, a mobile phone number represented one person rather than a household, the number of mobile‐phone numbers that were assigned to each participant was the only factor considered. The combined design weights for the mobile‐only and landline sample were computed by assuming an estimated proportion of 14% of German residents exclusively accessible via mobile phone in the 14 to 64 year old age group. The combined design weights were again adjusted, trimmed, and calibrated to the aforementioned characteristics of the German population between the ages of 14 to 64 years. The final combined weights ranged from 0.15 to 3.75. The use of sampling weights generally reduces potential bias of estimates. However, a loss of precision, i.e. increased standard errors of estimates, has to be considered. The maximum extent of such losses (assuming no correlation between the weight and characteristic to be measured in the survey) is expressed by the unequal weighting effect (UWE = 1 + [standard deviation of the weight/mean of the weight]2) which is 1.766 in the present study (Levy and Lemeshow, 2008). Thus, the effective sample size for population estimates based on the weighted telephone samples was at least equal to an unweighted sample of 8506 (15,022/1.766) individuals. In addition to the weights adjusted to the sample size, we computed weights adjusted to the size of the German population aged 14 to 64 years (N = 55,239,007). To allow for adequate statistical analyses considering the complex sampling design for variance estimation, variables indicating the primary sampling unit and sampling strata were provided with the final data set. As depicted in the left columns of Table 3, the weighting compensates for a higher participation proportion among females and highly educated individuals and a lower proportion among unemployed individuals and individuals reporting migration experience. Moreover, the sample weights compensate for the underrepresentation of mobile‐only participants due to the fixed sample sizes of both sampling frames. The deviation from the distribution of the characteristics in the general population that may result from the trimming of the sampling weights was below 1% for all variables (cf. Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the general population telephone samples, the German population and the sample undergoing the in‐depth clinical interview

| General population | Participants in the in‐depth clinical interviewb (N = 594) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone samples (N = 15,023) | Total population aged 14–64 yearsc | |||||

| Unweighted | Weighted | |||||

| n | % | % | % | n | % | |

| Sampling frame | ||||||

| landline | 14,022 | 93.3 | 86.0 | 86.0 | ||

| mobile‐only | 1001 | 6.7 | 14.0 | 14.0 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| female | 8300 | 55.3 | 49.4 | 49.4 | 113 | 19.0 |

| male | 6723 | 44.8 | 50.6 | 50.6 | 481 | 81.0 |

| Age (in years) | ||||||

| 14–17 | 947 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 12 | 2.0 |

| 18–24 | 1990 | 13.3 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 75 | 12.6 |

| 25–34 | 2848 | 19.0 | 17.5 | 17.6 | 126 | 21.2 |

| 35–44 | 3163 | 21.1 | 23.8 | 23.1 | 142 | 23.9 |

| 45–54 | 3437 | 23.0 | 22.7 | 23.3 | 163 | 27.4 |

| 55–64 | 2580 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 76 | 12.8 |

| no information | 58 | 0 | ||||

| Educational levela | ||||||

| still in school | 736 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 9 | 1.5 |

| no graduation | 177 | 1.2 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 11 | 1.9 |

| < 10 years of schooling | 2193 | 14.7 | 29.8 | 29.4 | 161 | 27.2 |

| 10 years of schooling | 4746 | 31.9 | 31.7 | 32.7 | 203 | 34.2 |

| >10 years of schooling | 7051 | 47.3 | 29.6 | 29.2 | 209 | 35.2 |

| no information | 120 | 1 | ||||

| Migration | ||||||

| born in Germany | 13,292 | 88.7 | 84.2 | 84.0 | 520 | 87.7 |

| born abroad | 1701 | 11.4 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 73 | 12.3 |

| no information | 30 | 1 | ||||

| Currently unemployed | ||||||

| no | 14,365 | 95.6 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 456 | 77.0 |

| yes | 658 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 136 | 23.0 |

| no information | 0 | 2 | ||||

The highest graduation level was classified according to the usual years of schooling for the respective grade.

Including all recruitment channels.

Data provided by the German Federal Statistical Office.

Threshold for the assessment of gambling problems

An interim analysis was done to test the sensitivity of different thresholds for the presentation of the case finding instrument among the first 1007 interviews of the landline telephone survey. For these interviews all participants reporting any lifetime gambling participation were assessed for lifetime gambling problems and 10 participants fulfilling the criteria for pathological gambling were identified. Among those participants five reported maximum losses (taking all wins and losses together) due to gambling or betting of more than 364€ or 599€ in a previous year. All of those participants reported more than 10 days, nine more than 50 days and eight more than 100 days with gambling participation in their previous life. To ensure 100% sensitivity for the detection of participants with pathological gambling we added the following skip rule to all subsequent interviews of the general population sample: if gambling or betting for money (in general or for any specific kind of gambling) on no more than 10 days during their lifetime was reported then the assessment of gambling problems was omitted.

Prevalence of past year gambling problems

Based on both telephone surveys and extrapolated to the German general population aged 14 to 64 we estimated that 193,028 inhabitants fulfilled the criteria for pathological gambling with symptoms within the past 12 months. Additionally 172,015 and 778,479 inhabitants were estimated to suffer from sub‐threshold gambling problems fulfilling 1–2 and 3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms, respectively. With respect to socio‐demographic characteristics increased prevalence rates of gambling problems were found for males, younger age groups, and individuals born abroad (cf. Table 4). Prevalence rates of pathological gambling but not sub‐threshold gambling problems were increased among subpopulations with lower educational level and among the unemployed.

Table 4.

Twelve‐month prevalence of gambling problems in the general population and socio‐demographic subgroups

| Sub‐threshold gambling problems | Pathological gambling | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‐2 criteria | 3–4 criteria | 5–10 criteria | ||||

| n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | |

| Total | 232 | 1.4 (0.1) | 43 | 0.3 (0.1) | 43 | 0.3 (0.1) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 153 | 2.0 (0.2) | 32 | 0.5 (0.1) | 37 | 0.6 (0.1) |

| Female | 79 | 0.8 (0.1) | 11 | 0.2 (0.1) | 6 | 0.1 (0.02) |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 14–30 | 112 | 2.1 (0.3) | 26 | 0.6 (0.1) | 35 | 1.0 (0.2) |

| 31–47 | 72 | 1.4 (0.2) | 10 | 0.2 (0.1) | 5 | 0.1 (0.1) |

| 48–64 | 47 | 0.7 (0.2) | 7 | 0.2 (0.1) | 3 | 0.04 (0.02) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| < 10 years of schoolinga | 30 | 1.0 (0.2) | 9 | 0.3 (0.1) | 14 | 0.6 (0.2) |

| 10 years of schooling | 79 | 1.5 (0.2) | 15 | 0.4 (0.1) | 14 | 0.3 (0.1) |

| >10 years of schooling | 99 | 1.6 (0.2) | 15 | 0.2 (0.04) | 10 | 0.1 (0.1) |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 9 | 1.2 (0.6) | 3 | 0.4 (0.3) | 5 | 1.1 (0.6) |

| Migration | ||||||

| born abroad | 35 | 2.2 (0.6) | 10 | 0.8 (0.3) | 12 | 0.9 (0.3) |

All estimates were based on the weighted general population telephone samples; estimates of standard error (SE) were corrected for cluster sampling and stratification. For total size of each subpopulation cf. Table 3.

Including no graduation.

High‐risk populations and in‐depth clinical interview

Recruitment among gambling location attenders

In the gambling locations, we addressed 3199 attendees, of whom 607 were excluded because they did not fulfill the age criterion or had insufficient German language skills. As a result of the difficulties in recruiting the gambling locations with only 9% giving permission for interviews (39/431) and a high proportion of subjects who were eligible but refused to participate, the planned sample size was not reached with 303 individuals completing the diagnostic interview (cf. Table 5). The cooperation rate (COOR3) was 11.7%. Because we were not able to realize a random selection of gambling locations and because of the inability to consecutively register attendees the calculation of a response rate was not possible. However, by definition, the response rate was below the cooperation rate. The mean interview duration was 25.2 minutes (SD = 7.9).

Table 5.

Recruitment for the in‐depth clinical interview across different channels

| General population samples | High risk population samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landline telephone survey | Mobile phone survey | Gambling location attendees | Volunteers contacting the project hotline a | Patients with specialized inpatient treatment for pathological gambling | |

| German‐speaking subjects 14–64 years | 26,736 | 1767 | 2592 | 412 | 52 |

| Not assessed for eligibility | 11,482 | 1986 | 2289 | 14 | ‐ |

| no valid contact data | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0 | |

| diseased, cognitive impaired | 364 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| target person not reached (again) | 709 | 1232 | 51 | 10 | |

| refused | 10,409 | 747 | 2175 | 4 | |

| Assessed for eligibility of the clinical interview | 14,022 | 1001 | 303 | 398 | ‐ |

| ≥ 1 DSM‐IV Criterion for pathological gambling | 1008 (100%) | 121 (100%) | 227 (100%) | 388 (100%) | ‐ |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (1–2 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 741 | 81 | 67 | 8 | |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 170 | 21 | 44 | 21 | |

| pathological gambling (>4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 97 | 19 | 116 | 359 | |

| Consent for further contact | 475 (47.1%) | 68 (56.2%) | 205 (90.3%) | 388 (100%) | ‐ |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (1–2 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 329 | 38 | 57 | 8 | |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 95 | 16 | 40 | 21 | |

| pathological gambling (>4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 51 | 14 | 108 | 359 | |

| Assigned for clinical interview | 226 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 93 (100%) | 311 (100%) | ‐ |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (1–2 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 81 | 0 | 9 | 2 | |

| sub‐threshold gambling problems (3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 94 | 0 | 7 | 10 | |

| pathological gambling (>4 DSM‐IV symptoms) | 51 | 13 | 77 | 299 | |

| Excluded | 10 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (1.3%) | ‐ |

| fulfillment ≥ 1 DSM‐IV symptoms not replicated | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| no valid contact data | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| moved abroad | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| insufficient German language capacities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| cognitive impaired | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| concerns about interviewer security | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Interview not realized | 51 (22.6%) | 3 (23.1%) | 26 (28.0%) | 6 (1.9%) | ‐ |

| target person never personally reached again | 12 | 2 | 11 | 1 | |

| target person reached again but interview could not be scheduled before end of study period | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | |

| explicit or implicit refusalb | 31 | 0 | 7 | 5 | |

| Interview completed | 165 (73.0%) | 10 (76.9%) | 66 (71.0%) | 301 (96.8%) | 52 |

Figures are numbers unless otherwise stated, column percentages in parenthesis

In response to media announcements, request of outpatient addiction counseling services, debt counselors, probation assistants, self‐help groups or other persons.

Implicit refusal was coded if a subject missed two interview appointments without reporting a comprehensible reason.

not applicable for the respective recruitment channel.

Recruitment of volunteers contacting the project hotline

The vast majority (96.6%) of the 412 volunteers contacting the project hotline completed the diagnostic interview (cf. Table 5). Among the volunteers who were interviewed separately by telephone in advance of the in‐depth clinic interview (n = 133), the interview duration was 23.0 minutes (SD = 7.0; the diagnostic interview was included in the in‐depth clinical interview for the remaining sample of volunteers).

Participation in the in‐depth clinical interview

Participants in the diagnostic interview were eligible for the in‐depth clinical interview if at least one symptom for pathological gambling according to DSM‐IV Criterion A had been fulfilled over their lifetime. Consent to be re‐contacted was given by 48% and 90% of the eligible individuals recruited via the general population telephone survey and the gambling locations, respectively. As depicted in Table 5, slightly lower rates were found for individuals with 1–2 DSM‐IV symptoms compared to individuals with 3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms and pathological gambling. Due to a limited budget and a restricted field period, only a selection of eligible individuals could be assigned to the in‐depth clinical interview. The selection aimed to optimize the number of completed interviews with the available resources for personnel and travelling taking into account the following priorities: (1) individuals with pathological gambling were preferred; (2) at least 50 individuals for both sub‐threshold categories of gambling problems should have been included; (3) individuals from the general population sample were preferred over other recruitment channels; (4) among the volunteers contacting the project hotline, infrequently reported ways of getting aware of the study (e.g. via debt counselors or probation assistants) were preferred. In total, 643 individuals had been assigned to the clinical interview. Among them, 15 had to be excluded after the initial contact attempt, and for 86 individuals, an interview could not be completed (cf. Table 5). With the additional 52 participating patients from specialized inpatient treatment for pathological gambling, the final total sample consisted of 594 participants that completed the in‐depth clinical interview. Among them, 88.2% (524/594) completed the paper‐pencil questionnaire after a systematic reminder procedure. A saliva sample was provided by 28.5% (169/594) of the participants. Consent to be contacted for a follow‐up study was given by 90.4% (537/594) of the participants.

An electronic registration of the interview duration was implemented in an update of the interview software during the field period. Thus, data regarding interview duration is available for 85% (485/594) of the interviews. The durations registered for each instrument administered in the individual case added up to a mean of 121.6 (SD = 47.57) minutes, excluding informal parts of the interview (e.g. study introduction, breaks, spontaneous conversation), instructions, collection of consent forms, times elapsed between the administration of single instruments and the collection of the saliva sample. The latter parts of the interview were estimated by the interviewers to last an additional 30 minutes on average. Although three hours of registered administration time was exceeded by 10.7% (52/485), the assessment was well tolerated, as only two interviews were prematurely abandoned, presumably due to participant burden (one participant experienced severe emotional distress and was overstrained by the interview, and another participant spontaneously left the interview location without giving reasons). One additional interview was incomplete because the interviewer decided to prematurely abandon the interview for security concerns (participant got intoxicated and presented psychotic symptoms during the interview).

As depicted in Table 6, three out of four participants who completed the clinical interview fulfilled the criteria for pathological gambling. The majority of participants with sub‐threshold gambling disorders, i.e. 1–2 symptoms (86.8%) and 3–4 DSM‐IV symptoms (78.4%), were recruited via the general population sample, and the majority of the participants with pathological gambling were among those contacting the hotline (65.3%), particularly in response to media announcements. About half of the participants (55.2%) reported gambling problems occurring within the last 12 months. The highest proportion of participants with 12‐month gambling problems was recruited among gambling location attendees (92.4%) and patients of inpatient clinics (96.2%). In contrast, one out of four (26.3%) participants recruited from the general population reported occurrence of gambling problems during the past 12 months. Socio‐demographic characteristics of subjects participating in the in‐depth clinical interview are described in the right columns of Table 3.

Table 6.

Participants of the in‐depth clinical interview by recruitment channel, diagnostic category, recency of gambling problems

| Recruitment | Sub‐threshold gambling problems | Pathological gambling | Symptoms within past 12 monthsa | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 criteria | 3–4 criteria | 5–10 criteria | 1–10 criteria | ||

| General population samples | 66 (37.3) | 58 (33.1) | 51 (29.1) | 46 (26.3) | 175 |

| mobile‐only survey | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 4 (40.0) | 10 |

| landline survey | 66 (37.3) | 58 (35.2) | 41 (24.8) | 42 (25.5) | 165 |

| Gambling location attendees | 7 (10.6) | 5 (7.6) | 54 (81.8) | 61 (92.4) | 66 |

| Volunteers contacting project hotline | 2 (0.7) | 9 (3.0) | 290 (93.3) | 171 (56.8) | 301 |

| in response to announcement/request of: | |||||

| self‐help groups | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 57 (100) | 28 (49.1) | 57 |

| outpatient addiction counseling services | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 58 (96.7) | 36 (60.0) | 60 |

| probation assistants | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (100) | 12 (54.5) | 22 |

| debt counselors | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 3 (60.0) | 5 |

| media | 2 (1.3) | 7 (4.5) | 148 (94.3) | 92 (58.6) | 157 |

| Inpatient clinics | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.8) | 49 (94.2) | 50 (96.2) | 52 |

| All recruitment channels | 76 (12.8) | 74 (12.5) | 444 (74.7) | 328 (55.2) | 594 |

Figures are numbers (row percentage based on all subjects of the respective recruitment category).

Participants with missing data on the item assessing the date of the last occurrence of gambling problems (n = 5) were classified as having symptoms within the last 12 months if any gambling was reported within this period and as having no problems within the last 12 months if no gambling was reported within this period.

Discussion

In this article, we described the study design that was completed within the PAGE program. The objectives of PAGE were to quantify the public health burden resulting from pathological gambling and to provide a large‐scale sample for subsequent in‐depth data analyses. Within a broadened epidemiological perspective, we considered the relevance of sub‐threshold diagnoses, comorbid substance use and mental disorders, course aspects, psychosocial resources, treatment utilization and processes of remission.

Several methodological innovations were implemented to overcome limitations of previous general population surveys: (1) The inclusion of a mobile‐only sampling frame may help to reduce coverage bias of previous landline telephone surveys. As indicated by health survey research, the omission of populations exclusively accessible via mobile‐phones might not sufficiently be compensated for by post‐stratification, especially when analyzing disparities in subpopulations (Call et al., 2011). Particularly, pathological gambling might be associated with financial problems precluding continuous payment of bills for a landline telephone as opposed to cell phones (e.g. with prepaid cards). (2) In contrast to surveys using brief screening instruments, we implemented a one‐step diagnostic procedure with a comprehensive, standardized, criterion‐based case finding instrument. In addition, skip rules steering the omission of symptom questions were empirically tested to ensure sufficient sensitivity. As indicated by our analysis higher threshold used in previous surveys (cf. Table 1) and implemented in the original gambling section of the CIDI may result in substantial underestimation. Accordingly, the use of respective skip rules should be carefully reconsidered for future surveys. (3) By covering lifetime gambling problems, the assessment allows analysis of course aspects and remission processes in a German sample. (4) Post‐stratification weights developed for the general population telephone samples considered an extended set of social indicators (i.e. educational level, unemployment, and migration), which have been previously found to be associated with pathological gambling and thus reduced the risk of selection bias.

Compared to studies from other nations the past year prevalence estimates of pathological gambling and sub‐threshold gambling problems in the present study were in the lower range (Sassen et al., 2011a; Stucki and Rihs‐Middel, 2007; Williams et al., 2012). Furthermore, our results replicated previous findings regarding subpopulations with increased prevalences, i.e. males, younger aged, lower educated, unemployed and migrant populations (Williams et al., 2012). Although comparisons with other general population surveys conducted in Germany so far are limited due to several methodological differences, the absolute differences in prevalence rates appear to be fairly small and our estimate exactly matched the mean of estimates detailed in Table 1. However, the relative differences of estimates among the available surveys were large with a three‐fold prevalence found in the highest compared to the lowest estimate. With respect to conclusions regarding the potential need for treatment options or secular trends this variation clearly was not satisfying. Several methodological features impacting on prevalence estimates have been proposed by previous research (Williams et al., 2012). However, no consistent pattern emerged when comparing the estimates and methodological differences of available Germany surveys (cf. Table 1).

Another important characteristic of the PAGE study design is in the addition of complementary recruitment channels used simultaneously with the general population telephone surveys. With respect to research questions related to descriptive epidemiology this may help to identify the omission of “hidden populations” by any specific recruitment. Stimulated by the capture–recapture method systematic approaches to combine different sampling frames or multiple places of observation have been applied in other fields of epidemiology (Verlato and Muggeo, 2000; Williams, 2010) and may be adapted for psychiatric epidemiology. By estimating the overlap of different PAGE sampling frames future strategies may be developed to derive sampling plans allowing a more complete coverage of the affected populations. With respect to research questions related to analytic epidemiology our approach may allow to learn more about sample selection bias and the generalizability of findings relying on only one sample. Furthermore, compared to convenience samples or designs using only one recruitment channel, our approach allows to analyze if associations of interest were dependent on the recruitment. For example, this strategy has been previously used in studies investigating natural recovery from alcohol dependence (Rumpf et al., 2000). Finally, our approach was an efficient strategy to generate one of the world´s largest samples of subjects suffering from gambling disorders, which were comprehensively phenotyped. Due to a sufficient sample size relevant subgroups could be analyzed by a case‐control methodology that has been established as a powerful alternative to cohort studies. The different PAGE samples could also naturally form relevant comparison groups. For example factors related to treatment utilization could be analyzed by comparing the inpatient or self‐help group sample to untreated cases from the general population sample.

For feasibility reasons and due to limited resources the design of PAGE included a two‐step assessment procedure. Thus, the more comprehensive information from the clinical interview was only available for subjects with lifetime gambling problems and direct comparisons with individuals experiencing no gambling problems in the past are restricted to information gathered in the diagnostic interview. However, in light of previous evidence confirming substantial rates of psychiatric comorbidity (Petry et al., 2005), subgroups of PAGE participants defined by other mental disorders could be analyzed as well. Comparing such data to studies using other sequences of sampling may be fruitful to discover the relevance of gambling problems in other mental disorders with respect to related mechanisms of psychopathology, recovery, or treatment utilization.

Several limitations of the present study have to be considered for subsequent studies which were based on the PAGE data. (1) Because the primary source of data collection relied on self‐reports, reporting bias cannot be precluded. With respect to prevalence estimation in person assessment, i.e. face‐to‐face or telephone, was more likely to be subject to a social desirability bias compared to self‐administered assessments, i.e. online or postal mode (Bowling, 2005). However, in person interview administration is regarded as a gold standard in psychiatric epidemiology because of several other possible sources of bias, e.g. lower item non‐response, being participants' preferred mode, or allowing measures to ensure question comprehension. (2) A further limitation of our study is that we did not cover the institutionalized or non‐German speaking populations that may differ with respect to the prevalence of gambling problems and related factors. (3) Because we aimed to provide national estimates by the telephone survey and at the same time expanded the assessment of identified individuals with gambling problems by a face‐to‐face interview we had to restrict the number of communities, i.e. the primary sampling unit, to keep traveling costs at a reasonable level. The fairly small number of included communities may increase the sampling error. However, stratification was used to at least ensure a nationally representative selection of communities with respect to the number of inhabitants and the density of electronic gambling machines. (4) A substantial part of subjects addressed in the telephone surveys refused to participate in the study. To correct for a potential selection bias in the general population sample we provided extended sample weights including adjustment for social indicators. The downside of this procedure is that the effective sample size is reduced to a minimum of 57% when analyzing characteristics that are uncorrelated with the sample weights. Although, the response rates in the PAGE telephone surveys are comparable with other recent general population gambling studies conducted in Germany (cf. Table 1) non‐participants might differ from participants with respect to relevant but unmeasured characteristics. Irrespective of specific survey designs, an increase of refusal in epidemiological studies has been observed over the past decades (Galea and Tracy, 2007). Higher participation rates have been reported in studies involving face‐to‐face recruitment but particularly in studies with nationwide sampling costs would increase dramatically. The development of brief but valid assessments that lowers the burden for participants and the use of prepaid monetary incentive provided with announcement letters may help to at least partially reduce non‐participation in future studies (Galea and Tracy, 2007). The later measure is precluded with sampling involving random digit dialing procedures and speaks in favor of sampling from official population registries. Depending on national availability and accessibility, registry based sampling could be regarded as a gold standard that may also provide additional information for a refinement of the sampling plan or evaluation of non‐response (Romild et al., 2014). Another cost saving opportunity developed in the United States may be seen in address‐based sampling, i.e. use of a sampling frame that may allow higher response rates and coverage of mobile‐only households compared to conventional random digit dialing surveys (Link et al., 2008). However, to our knowledge the latter option was not available in Germany and registration office based sampling was not feasible because each of the German communities had their own inhabitant register and the project duration of one year did not allow gaining necessary permissions in all selected communities. With respect to the sampling of gambling location attenders we failed to realize a random sample. Both, the participation rates of the gambling locations and attenders were very low. Therefore, those data should be regarded as a further convenience sample. As an advantage, this approach was particularly effective in recruiting participants with current disorders without previous contact to the treatment system. Finally, the low rate of participants providing a saliva sample should be carefully considered for subsequent analyses. Future research may identify more refined strategies to optimize completeness of data for surveys collecting bio‐material in addition to self‐report data.

The PAGE program provides a rich epidemiological database, setting the ground for extended research in the field of gambling. This may include longitudinal studies using PAGE participants as a baseline sample. To ensure broad use of the data, it is intended to provide a scientific use file for non‐commercial research purpose to interested scientists. Innovations embedded in the project design may also contribute to methodological advances in the field of psychiatric epidemiology.

Authors' contribution

UJ, CM and HR outlined the study concept in the grant proposal. CM, AB, AW, CJ, SB, SG, DS, SP, TH, FJ, ML, VP, RG, DH, GB, UJ and HR substantially contributed to the final study design. DH was responsible for organizing the fieldwork and quality control of the general population telephone surveys, the recruitment and telephone interviews with gambling location attendees and parts of the telephone interviews conducted with volunteers. RG computed the sampling weights for the general population surveys. AW, CJ, SB, SG, DS, SP, AB conducted the clinical interviews. CM, NK, DG were responsible for data preparation and checks and also built up the final database. CM, NK, DG, AB, HR took part in the data analyses. CM drafted the initial version of the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the 16 German federal states, and the decision for funding was made by a review board based on a grant proposal outlining the study concept. The funding included no further restriction regarding the study design, analysis, interpretation and publication of the data.

The authors would like to thank Dipl.‐Ing. Christian Goeze for programming the project management software, Diana Klinger for the field‐management of the clinical interviews and M.A. Angelika Steinwede for the field‐management of the telephone surveys. Thanks are extended to the following scientists providing support and the members of the advisory board: M. A. Sven Buth, Prof. Dr John Cunningham, PD Dr Ralf Demmel, Prof. Dr Harald Freyberger, Dipl.‐Päd. Ilona Füchtenschnieder‐Petry, Dipl.‐Psych. S. Giralt, Prof. Dr Hans‐Jörg Grabe, Dr Ulfert Hapke, Prof. Dr Klaus Junghanns, Dr Tagrid Lemenager, Prof. Dr Karl Mann, Prof. Dr Gerhard Meyer, Jürgen Trümper, Dr Klaus Wölfling. Further, the authors are grateful for the cooperation of the following inpatient clinics providing specialized treatment for pathological gambling: AHG Klinik Schweriner See, Fachkrankenhaus Nordfriesland, Klinken Daun, Fachklinik Fredeburg, Salus Klinik Wilhemsheim, Klinik Bad Herrenalp, Therapiezentum Brückle in Buggingen. Finally, the authors would like to thank all participants and supporting institutions for their contributions to the project.

Meyer C., Bischof A., Westram A., Jeske C., de Brito S., Glorius S., Schön D., Porz S., Gürtler D., Kastirke N., Hayer T., Jacobi F., Lucht M., Premper V., Gilberg R., Hess D., Bischof G., John U., and Rumpf H.‐J. (2015) The “Pathological Gambling and Epidemiology” (PAGE) study program: design and fieldwork, Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res., 24, pages 11–31. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1458.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (4th ed., text revision), American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Arlington, VA: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel C.S., Frerichs R.R., Clark V.A., Yokopenic P.A. (1982) Measuring depression in the community: a comparison of telephone and personal interviews. Public Opinion Quarterly, 46(1), 110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G., Rumpf H.J., Hapke U., Meyer C., John U. (2003a) Deutsches Coping‐Behaviours Inventory (CBI‐G) In Glöckner‐Rist A., Küfner H. (eds) Elektronisches Handbuch zu Erhebungsinstrumenten im Suchtbereich (EHES), Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G., Rumpf H.J., Hapke U., Meyer C., John U. (2003b) Die Skala zur Erfassung sozialen Drucks (SSD) In Glöckner‐Rist A., Küfner H. (eds) Elektronisches Handbuch zu Erhebungsinstrumenten im Suchtbereich (EHES), Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. (2005) Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health (Oxford), 27(3), 281–291. DOI: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühringer G., Kraus L., Sonntag D., Pfeiffer‐Gerschel T., Steiner S. (2007) Pathologisches Glücksspiel in Deutschland: Spiel‐ und Bevölkerungsrisiken. Sucht, 53(5), 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Buth S., Stöver H. (2008) Glücksspielteilnahme und Glücksspielprobleme in Deutschland: Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Repräsentativbefragung. Suchttherapie, 9(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Call K.T., Davern M., Boudreaux M., Johnson P.J., Nelson J. (2011) Bias in telephone surveys that do not sample cell phones: uses and limits of poststratification adjustments. Medical Care, 49(4), 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen H., Kis B., Hirsch O., Philipsen A., Henneck M., Panczuk A., Pietrowsky R., Hebebrand J., Schimmelmann B.G. (2011) German validation of the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales‐self‐report (CAARS‐S) I: Factor structure and normative data. European Psychiatry, 26(2), 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.A., Hodgins D.C., Toneatto T. (2009) Natural history of gambling problems: results from a general population survey. Sucht, 55(2), 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Denis C., Fatseas M., Auriacombe M. (2012) Analyses related to the development of DSM‐5 criteria for substance use related disorders: 3. An assessment of Pathological Gambling criteria. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 122(1–2), 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosch G.E., Krieger W. (1995) Fragebogen zur Erfassung des Gesundheitsverhaltens (FEG), Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . (2011) Special Eurobarometer 362: E‐Communication Household Survey Retrieved December 31, 2013, from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_362_en.pdf.