Abnormal lingual movements are not uncommon. A rare lingual syndrome consisting of involuntary wave-like lingual movements has been labeled as “galloping tongue.”1 Herein, we report a patient with galloping tongue syndrome carrier of a mutation in the PRRT2 gene.

Clinical findings

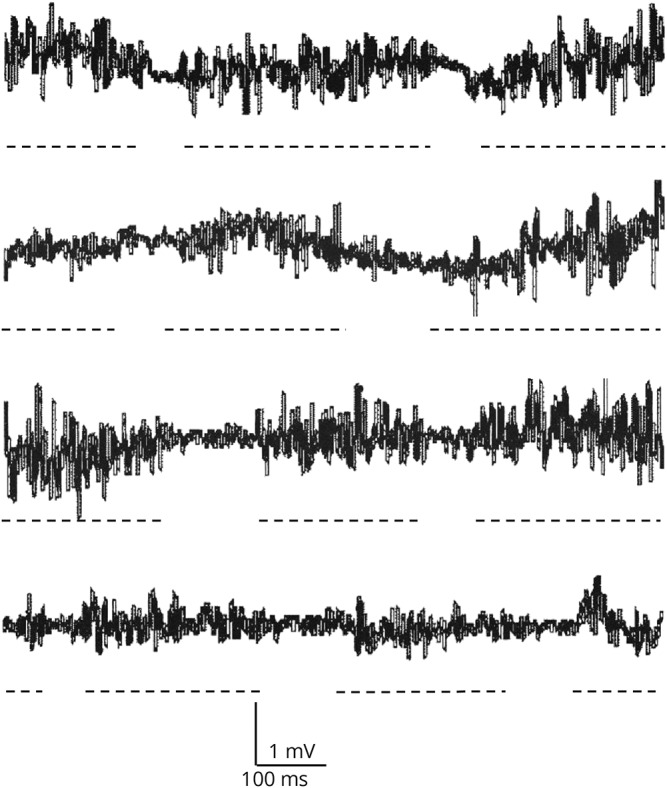

A 17-year-old woman presented with involuntary tongue movements within the past years, appearing only with tongue protrusion. “Wavy” contractions of the tongue were evident during sustained tongue protrusion (video 1). The contractions developed immediately after sticking the tongue out, persisted during protrusion, and disappeared while at rest. The movements could not be disrupted, suppressed, or entrained with examiner-given rhythmic activities. Abrupt body movements, sleep deprivation, or coffee intake did not affect the abnormal movement. There was no history of exposure to neuroleptic medication or head trauma. The tongue contractions seemed to begin in the posterior midline region and progress in a wavy fashion to the anterior and lateral parts of the tongue. The results of routine hematologic and blood biochemistry including thyroid function tests, copper levels, and ceruloplasmin were normal. A urine toxicology screen did not reveal the presence of any drug of abuse. An electrophysiologic study with electrodes applied on the surface of the tongue showed no electrical activity while at rest. With tongue protrusion, the EMG activity was segmented in discharges of 200–300 ms duration and separated by brief periods of silence, with an approximate frequency of 3 per second (figure 1). Her brain MRI was normal. Because the movement disorder did not affect the patient's orolingual function, no treatment was started.

Figure 1. Electromyographic activity of the tongue recorded with surface electrodes during tongue protrusion.

Discharges of 200–300 ms duration and separated by brief periods of silence, with an approximate frequency of 3 per second were observed during tongue protrusion. Broken lines have been added to underline each EMG discharge.

17-year-old woman with tongue movements appearing only during tongue protrusion. “Wavy” contractions of the tongue are evident during sustained tongue protrusion.Download Supplementary Video 1 (9.1MB, mov) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000377_Video_1

The patient's sister, a 14-year-old, presented with short episodes of choreo-dystonic movements of the left arm and neck that appeared when she started to run since the age of 10. These episodes usually last a few seconds and occur at least 10 times per day. Her consciousness level was normal during episodes. Her medical history included migraine. She was diagnosed as having paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias (PKD). Treatment with carbamazepine led to a complete remission of the movements.

There was no family history of epilepsy or infantile convulsions. The patient's mother had severe recurrent migraine headaches. Her maternal cousin had been diagnosed with PKD.

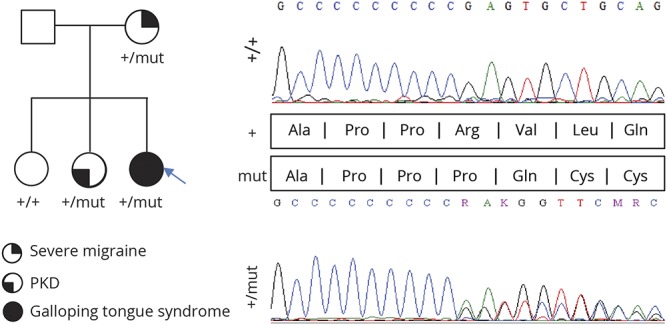

The patient, her 2 sisters (1 healthy and the other affected with PKD), and their mother were available for PRRT2 mutation screen (figure 2). Direct sequencing identified a heterozygous truncating mutation in the proband, her mother, and the symptomatic sister: GRC37/hg19: chr16:29825025 GA/A, NM_145239: c.650delG, producing the amino acid change NP_660282.2: p.R217Qfs*12. This variant is not listed in public genomic databases, including ExAC (exac.broadinstitute.org/).

Figure 2. PRRT2 mutational analysis in a family with paroxysmal neurologic disorder.

Right, PRRT2 electropherograms: Top, wildtype sequence in the proband's healthy sister; and bottom, guanine deletion at position 650 occurs at the end of a cytosine streak, a well-known hotspot in PKD. The variant results in a premature termination of transcription (p.R217Qfs*12). Left, family tree with various phenotypes indicated.

Discussion

Herein, we describe a patient with “galloping tongue” syndrome who was positive for the p.R217Q fs*12 mutation in the PRRT2 gene. Galloping tongue is an uncommon movement disorder.1–5 The characteristics of these lingual movements have been variably described as transverse contractions, twisting, or undulating movements.2–5 Although these movements were present with the tongue at rest in most of the reported patients, in some cases the movements were also observed during sustained action.

Our patient had a mutation in the PRRT2 gene known to be associated with PKD.6 However, she did not have the typical paroxysmal dyskinesias seen in PKD. Her abnormal movements were triggered by action but were not paroxysmal because they were present as long as the voluntary movement motion persisted, resembling an action dystonia. The topography of dyskinesia, isolated to the tongue, was also uncharacteristic of PKD. Still, we believe that the PRRT2 mutation could be linked to the patient's movement disorder because it is action related and known causes of the disorder have been ruled out. Furthermore, the phenotype of PRRT2 mutations is not limited to dystonia and chorea typical of PKD, but episodic ataxia and paroxysmal torticollis have also been described.7 Seizures and migraine seem to be also part of the clinical spectrum.6

The cause of the lingual movements in our patient remains uncertain. A functional movement disorder seemed unlikely because the movement disorder could not be disrupted, suppressed, or entrained with examiner maneuvers, which had no impact in the patient's life, and there was no obvious gain for the patient. The study of similar cases and additional PRRT2 families will eventually clarify whether the “galloping tongue” syndrome is indeed a previously unrecognized manifestation of PRRT2 mutations.

Author contributions

D. Vilas and E. Tolosa: drafting/revising the manuscript and conceptualization of the study. A. Marcé-Grau and A. Macaya: genetic analysis and revising the manuscript. J. Vall-Solé: electrophysiologic study and revising the manuscript.

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

Disclosures available: Neurology.org/NG.

References

- 1.Keane JR. Galloping tongue: post-traumatic, episodic, rhythmic movements. Neurology 1984;34:251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saddichha BA, Talukdar D. Serpentine tongue syndrome associated with risperidone long-acting injection treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34:657–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagappa M, Sinha S, Saini J, Bindu P, Taly A. Undulating tongue in Wilson's disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014;17:225–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prashantha DK. Serpentingue tongue: a rare manifestation following initiation of levodopa therapy in a patient with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2009;15:718–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheehy SHC, Lawrence T, Thevathasan AW. Serpentine tongue. A lingual dyskinesia. Neurology 2008;70:e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Méneret A, Grabli D, Depienne C, et al. . PRRT2 mutations: a major cause of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia in the European population. Neurology 2012;79:170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelnovo G, Renard D, De Verdal M, Luc J, Thouvenot E, Riant F. Progressive ataxia related to PRRT2 gene mutation. J Neurol Sci 2016;367:220–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

17-year-old woman with tongue movements appearing only during tongue protrusion. “Wavy” contractions of the tongue are evident during sustained tongue protrusion.Download Supplementary Video 1 (9.1MB, mov) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000377_Video_1