Abstract

Women in academia receive fewer prestigious awards than their male counterparts. This gender gap may emerge purely from structural factors (e.g., gender differences in time spent in academia, institutional prestige, and academic performance), or from a combination of structural and psychological factors (e.g., gender schemas). To test these competing predictions, we assessed the independent contribution of year of degree, institutional prestige (a composite of prestige of PhD school and current affiliation), academic performance (total publications, total cites, and h-index), and gender to the prestige of awards earned by male (N = 298) and female (N = 134) academic neuroscientists. Award prestige was determined by an independent set of neuroscientists. Men earned more prestigious awards than women after controlling for institutional prestige, year of degree, and total publications. But after controlling for total citations or h-index, no gender difference appeared. Mediation analyses revealed that the gender disparity in awards was mediated by a gender difference in total cites and h-index. There was a reciprocal effect as well, in that the gender disparity in total cites and h-index was partially mediated by awards. These results point to an indirect path by which psychological factors may create gender disparities in academic awards: gender schemas may lead to women’s papers receiving fewer citations than men’s papers, resulting in more prestigious awards for men than for women. Additionally, our results suggest that gender disparities in awards and citations may reinforce each other. Practical implications for promoting gender equality in academic awards are discussed.

Keywords: gender bias, gender inequality, awards, prestige, neuroscience

Brief Abstract

Women in academia receive fewer prestigious awards than their male counterparts. Why this gender gap emerges, however, remains poorly understood. Thus, we tested multiple hypotheses about the proximate cause of the gender gap in award prestige. Our findings suggest that the gender gap in award prestige may emerge in part from gender schemas that portray women as warmer and less competent than men. Specifically, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that gender schemas lead to women’s papers receiving fewer citations than men’s papers, which in turn results in more prestigious awards for men than for women. Additionally, our results suggest that gender disparities in awards and citations may reinforce each other. Practical implications for promoting gender equality in academic awards are discussed.

Women in academia receive less recognition for their work compared to men. Controlling for representation in their field, women give fewer invited colloquia at universities (Nittrouer, et al, 2018), and are underrepresented among invited presenters at conferences (for assistant and associate professors in social psychology, see Johnson, Smith, & Wang, 2017; for evolutionary biology, see Schroeder et al, 2013). Women also receive fewer prestigious awards from professional academic societies in a range of fields (Lincoln, Pincus, Koster, & Leboy, 2012; Popejoy & Leboy, 2012; Silver et al, 2018).

What produces the gender gap in recognition for academic achievement? The disparity could emerge from structural factors, psychological factors, or both (see Heilman, Manzi, & Braun, 2015; Jones, Arena, Nittrouer, Alonso, & Lindsey, 2017; Stewart & Valian, 2018; Valian, 1998), but it has been difficult to disambiguate these competing possibilities. Overcoming this barrier is critical: the gender gap is a prima facie challenge to academia as meritocratic, and may discourage aspiring women from continuing in their field. To address the theoretical and practical issues posed by gender differences in academic achievement, we take as a test case gender differences in awards to faculty in neuroscience – one of the fastest growing disciplines in science.

Possible Reasons for Gender Disparities in Awards

Structural Factors

Gender disparities in awards may emerge from gender differences in job placement. Women are less concentrated than men in high-prestige institutions, where resources to support research are extensive, teaching occupies less time, institutional rewards are more directed at scholarship than teaching, and graduate students are better prepared (Stewart &Valian, 2018; Xie & Shauman, 1998). Thus, gender disparities in placement may yield gender disparities in productivity, which may in turn lead to gender disparities in awards (Duch, et al, 2012; Xie & Shauman, 1998).

Beyond job placement, structural factors that may lead to gender disparities in awards include demographic inertia and homophily. There are more older men than older women in most academic fields and awards tend to go to older people. Thus, one would expect fewer women than men to receive awards on the basis of age alone. With respect to homophily, men’s networks may include fewer women than women’s networks do; since men have more awards and are likely to nominate people they know, their homophily will result in proportionally more nominations of men.

Finally, there may be a reciprocal influence between awards and citations: women’s papers may receive fewer citations in part because they have fewer awards. Winning a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Award, for example, is associated with a subsequent small but significant increase in citations to work published before the award was bestowed (Azoulay, Stuart, & Yang, 2013). Thus, a failure to receive an early award that could draw attention to one’s work can result in fewer citations to that work, in turn affecting the likelihood of later awards.

Psychological Factors

Gender disparities in awards may also emerge from the tendency to judge women as less competent and more nurturant and communal than men in professional settings, leading directly to gender disparities in awards (Jones, et al, 2017; Valian, 1998). Such judgments need not reflect conscious attitudes toward women, but instead could reflect implicit gender schemas (e.g., Heilman, 2001; Heilman, Manzi, & Braun, 2015; Valian, 1998). The presence of women on a colloquium, awards, or organizing committee might counter such schemas by highlighting women’s competence. And women do receive more awards when committees include women (Casadevall & Handelsman, 2014; Klein et al, 2016; Lincoln, et al., 2012; Nittrouer, et al., 2018; Sardelis, & Drew, 2016).

In addition to a direct path from gender schemas to gender disparities in awards, multiple indirect paths are possible. One indirect path runs through productivity: the gender schema of women as more nurturant and communal than men may lead people to request more departmental service of women – an imbalance which would be expected to subtract from women’s research productivity. Consistent with this, women are asked to perform and do perform disproportionately more departmental service than men and produce fewer publications (Jones, et al, 2017; O’Meara, Kuvaeva, Nyunt, Waugaman, & Jackson, 2017; Valian, 1998; van Arensbergen, van der Weijden, & Van den Besselaar, 2012).

A second indirect path by which gender schemas may influence awards runs though citations: the gender schema of women as less competent than men may result in women’s papers receiving fewer citations than men’s papers. Women may in turn receive fewer prestigious awards than men, because citations reflect norms about whose work is important (MacRoberts & MacRoberts, 2018). In line with this, women are cited less than men, independent of the quality of their work and even when they publish in high-impact journals (Bendels et al, 2018; Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell, 2018; Larivière, Ni, Gingras, Cronin, & Sugimoto, 2013; Maliniak, Powers, & Walter, 2013; but see Lynn, Noonan, Sauder, & Andersson, 2019, for a report of equal citations of men and women). Relatedly, women cite themselves markedly less than men self-cite (King, Bergstrom, Correll, Jacquet, & West, 2017). Those data suggest that one problem is how women’s performance is perceived, rather than their actual performance.

A third indirect path by which gender schemas may influence awards runs through measures like the h-index. A necessary consequence of fewer publications and fewer citations is a smaller h-index, where h is the number of papers having received that number of citations or more. (An h of 30 means the author has 30 papers that have been cited at least 30 times.) In psychology, to give one example, women have a lower h-index than men (Geraci, Balsis, & Busch, 2015).

State of the Evidence

Are gender disparities in awards due to structural factors, psychological factors, or both? The answer to this question is unclear, as few studies have examined gender disparities in awards while controlling for other plausible variables that would lead to awards. Some available evidence, however, suggests that psychological factors may play an important role. For instance, King, Angoff, Forrest, and Justice (2017) estimated the independent contributions of multiple factors to the receipt of awards by senior medical school students at Yale University, all of whom must write a research paper in their final year (King, et al., 2017). Over a 13-year period, from 2003 to 2015, equal numbers of men and women submitted senior papers, equal numbers of men and women were nominated for awards for those papers, and equal numbers of men and women overall received awards. Only about 5% of the 1000+ papers received highest honors. Here, women were underrepresented, receiving slightly less than a third of highest honors. Thus, although women received half of all awards, they were a minority of the most selective awards. Even after controlling for factors that influenced awards, such as type of laboratory, mentor experience with successful students, and type of research (experimental vs clinical), women were approximately half as likely as men to receive the highest honor. As in a 1997 Swedish study of post-doctoral applicant success (Wennerås & Wold, 1997), the awards committee gave better scores to men than women, especially at the level necessary for highest honors. In light of these findings, we hypothesize that gender disparities in awards to faculty in neuroscience are attributable in part to psychological factors – namely, direct or indirect effects of gender schemas.

Present Study

The present study estimates the independent contributions of structural and psychological factors to gender disparities in awards to neuroscience faculty. To maximize the likelihood that we examined only active researchers who would be eligible for awards we restricted our sample to individuals who were first or last authors on an accepted poster during an eight-year period at meetings of the Society for Neuroscience, were tenured or tenure-track faculty, and had a curriculum vita (CV) posted online (87% of tenured and tenure-track faculty had their CV posted online, which did not vary as a function of gender, p = .739).

The restriction to first or last author helped ensure that the person most responsible for the research (the first author) was included, as was the likely person in whose lab the research was conducted (the last author). Although we cannot be sure that research was conducted in the lab of the last author, or that the first author was responsible for the research, we reasoned that including only first and last authors minimized our likelihood of including non-active neuroscientists in our analyses. The restriction to tenure line individuals ensured that only people with full time positions in academia – those most likely to be candidates for awards – were included. The restriction to individuals with on-line CVs was partly a matter of convenience and partly a way of choosing a sample that was professionally active.

We also limited our sample to people who specialized in the same subfield. Different subfields have different percentages of men and women, have different norms with respect to total research output and citations, and are eligible for different awards. We thus examined only neuroscientists whose poster was in the human behavior and cognition poster session, which we selected because it was among the largest poster sessions and thus allowed us to maximize our sample size.

We include measures for year of degree, prestige of degree-granting and present institution, number of publications, number of citations to publications, and gender to determine whether men and women receive equal awards. However flawed publications and citations are as measures of performance, they are commonly used in determinations of hiring and promotion.

Method

Participants

We analyzed curriculum vitae (CV) and publication data from male (n = 298) and female (n = 134) academic neuroscientists. To be included in our sample, researchers must have met the following criteria: i) position as first or last author of a poster accepted for presentation in the Human Behavior and Cognition category at the Society for Neuroscience conferences between 2003 and 2011; ii) status as tenure track or tenured faculty member at a US college or university during the same year at least one of their posters was accepted; iii) PhD degree in the year 1960 or later; and iv) availability of an online CV.

The presenter index on the Society for Neuroscience website allowed us to identify 5726 unique first plus last authors with posters accepted in the Human Behavior and Cognition category at the annual Society for Neuroscience conference between 2003 and 2011. Of those authors, 1054 (18%) were tenure track (or tenured) faculty affiliated with a US college or university who had earned their PhD in the year 1960 or later. Of those 1054 eligible presenters, 532 (50%) posted their CV online. One hundred individuals who were randomly selected and asked to rate the prestige of awards were excluded from analyses, leaving a total of 432 individuals.

We determined each individual’s gender based on pictures and, when available, gender-specific pronouns found in their bios. We referenced the presenter index on the Society for Neuroscience website to identify the number of times they were the first or last author of a presented poster between 2003 and 2011.

Curriculum Vitae (CV) Data Collection

We collected the following data from eligible participants’ public CVs: i) year of PhD (range from 1960–2009); ii) PhD-granting institution; iii) institution where they were first employed; iv) current institution where employed; v) names of awards and prizes; and vi) date of most recent CV update.

We used each researcher’s most recent publication date as their most recent CV update in the absence of a note specifying when they made their last update. We coded the world ranking for each of the three institutions (PhD institution, first job, and current employer) according to the Shanghai Academic Ranking of World Universities (Shanghai Ranking Consultancy, 2011). The lower the rank the more prestigious the institution: Ranks 1–10 received a score of 8, ranks 11–20 received a score of 7, ranks 21–50 received a score of 6, ranks 51–100 received a score of 5, ranks 101–200 received a score of 4, 201–300 received a score of 3, 301–400 received a rank of 2, and ranks 401–500 received a score of 1. Because institution ranks of PhD institution, first job, and current employer were highly intercorrelated (all rs > .8), we computed their mean to create a single composite institution score. Institution score could thus range from 1–8. Individuals at unranked schools (N = 18) were excluded.

Publication Data

We collected the following publication data for each author using the software program Publish or Perish (Harzing, 2007): number of total publications, number of total citations, and h-index. We log transformed all publication data to normalize their distributions.

Although it is one of the most reliable sources of publication data, Publish or Perish searches sometimes include errors. The program fails to distinguish between authors with the same initials and last name and sometimes lists alternate titles as separate publications (e.g., The brain on drugs vs. brain on drugs, The), which inflates an author’s publication total and possibly dilutes their highest cite total. To avoid these issues, we manually removed all erroneous author inclusions by identifying those that corresponded to publication titles clearly incompatible with the target author’s line of research. We also aggregated data for all publications with alternate spellings.

Award Score

We identified all major achievement-based awards and prizes for which neuroscientists specializing in human behavior and cognition are eligible (N = 42, of which we used 30; see Appendix for full list). We excluded awards if they were not primarily given for research excellence and awards named after women (Janet T. Spence, Janet Rosenberg Trubatch, Mika Salpeter). (We excluded awards named after women in case awards committees view these as more “appropriate” for women scientists. However, results did not differ if we included awards named after women.)

The total amount of prestige that awards confer on an individual scientist is a joint function of the number of awards that the scientist has and their quality. To compute a total award score for each scientist in our sample, it was necessary to measure the prestige of each award. We emailed 100 randomly selected members of our sample and asked them to complete an online questionnaire designed to assess the prestige of awards and prizes in neuroscience. (These individuals were excluded from all subsequent analyses.) For each award and prize included in our sample, respondents evaluated prestige on a 9-point scale (1=not at all prestigious; 9=extremely prestigious). Inter-rater reliability was good among the 52 neuroscientists (36% female) who completed the survey (κ = .84). We assigned each award a prestige score equal to its mean rating (all of which were unmoderated by the gender of the rater), and assigned each participant an award score equal to the sum of their awards’ prestige scores.

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for all variables. The awards scores are for all awards, including those named after women.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Total | Women | Men | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | |

| Award Score | 37.9 | 25.02 | 0 | 77 | 30.0 | 23.21 | 0 | 72 | 41.5 | 25.03 | 0 | 77 |

| Degree Year | 1994 | 8.84 | 1960 | 2009 | 1996 | 8.13 | 1965 | 2009 | 1993 | 8.99 | 1960 | 2009 |

| Institution Score | 5.29 | 1.84 | 1.67 | 8 | 4.85 | 2.22 | 1.67 | 8 | 5.48 | 1.61 | 1.67 | 8 |

| Total Publications | 185 | 154.75 | 10 | 946 | 120 | 124.67 | 10 | 888 | 214 | 158.31 | 11 | 946 |

| Total Citations | 11,890 | 10,547 | 372 | 70,137 | 7,271 | 7,121 | 372 | 46,267 | 13,967 | 11,170 | 575 | 70,137 |

| h-lndex | 34 | 21.42 | 5 | 106 | 21 | 12.17 | 5 | 96 | 40 | 22.09 | 6 | 106 |

Results

As shown in Table 1, which lists the descriptive statistics for all variables, the ranges of scores for all variables except gender were large. For example, award scores ranged from 0 to 77; year of degree ranged from 1960 to 2009; institution score ranged from 1.67 to 8; total publications ranged from 10 to 946; total cites ranged from 372 to 70,137; and h-indexes ranged from 5 to 106.

Correlations among all variables of interest are displayed in Table 2. Being male (rather than female) was associated with an earlier date of PhD attainment (r(432) = −.16, p = .001), working at higher ranked universities (r(432) = .30, p < .001), and having more total publications (r(432) = .323, p < .001), total cites (r(432) = .34, p < .001), and a higher h-index (r(432) = .43, p < .001). Being male was also significantly correlated with the main variable of interest – award scores (r(432) = .21, p < .001).

Table 2.

Correlations

| 1. Gender | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. Degree Year | −.16** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. Institution Score | .30*** | .05 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. Total Publications | .32*** | −.52*** | .10* | -- | -- | -- |

| 5. Total Citations | .34*** | −.43*** | .19*** | .50** | -- | -- |

| 6. h-lndex | .43*** | −.61*** | .14** | .72** | .62** | -- |

| 7. Award Score | .21*** | −.34*** | .11* | .22*** | .31*** | .35*** |

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001

Note. Gender is scored 0 for female and 1 for male.

Year of degree, as would be expected, was negatively correlated with total publications (r(432) = −.52, p < .001), total cites (r(432) = −.43, p < .001), h-index (r(432) = −.61, p < .001), and award score (r(432) = −.34, p < .001). Institution prestige had a significant, positive correlation with total publications (r(432) = g.10, p = .037), total cites (r(432) = .19, p < .001), h-index (r(432) = .14, p = .003), and award score (r(432) = .11, p = .023). Together, year of degree and institution prestige accounted for 13% of the variance in award score (R2 = .13, F(2, 411) = 31.6, p < .001). Not surprisingly, total publications, total cites, and h-index were highly intercorrelated (all rs > .5).

Given the pattern of correlations, the relationship between gender and award score could be due to gender differences in year of degree, current institution ranking, total publications, total cites, h-index, or some combination thereof. To test those possibilities, we performed three regressions (see Table 3). Models regressed gender, year of degree, current institution ranking, and one of the three performance metrics (total publications, total cites, or h-index) on award score. All three models accounted for a significant amount of variance in award score.

Table 3.

Regression models predicting award score

| Model 1 (R2 = .15) | b | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Year | −.88*** | .15 |

| institution Score | 1.34† | .74 |

| Total Publications | .61 | 1.67 |

| Gender | 6.74* | 2.75 |

| Model 2 (R2 = .17) | b | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Year | −.70*** | .14 |

| Institution Score | 1.00 | .14 |

| Total Citations | 4.44** | 1.32 |

| Gender | 4.52† | 2.72 |

| Model 3 (R2 = .16) | b | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Year | −.63*** | .16 |

| institution Score | 1.15 | .74 |

| h-index | 6.77** | 2.48 |

| Gender | 4.10 | 2.83 |

P < .01,

P < .05,

P < .01,

P < .001

Model 1’s performance metric was total publications (R2 = .15, F(4, 409) = 17.78, p < .001). Gender had a significant effect on award score (b = 6.74, SE = 2.75, p = .014), accounting for 1.3% of the variance. Specifically, men had higher award scores than women, over and above a marginal effect of institution prestige, (b = 1.34, SE = .74, p = .073) and the significant effect of year of degree (b = −.88, SE = .15, p < .001). Total publications was not significant (b = .61, SE = 1.67, p = .716).

Model 2’s performance metric was total citations (R2 = .17, F(4, 409) = 21.04, p < .001). In this model, only total citations (b = 4.44, SE = 1.32, p = .001) and year of degree (b = −.70, SE = .14, p < .001) were significant predictors of award score. Neither institution score (b = 1.40, SE = .74, p = .179) nor gender (b = 4.52, SE = 2.72, p = .097) were significant predictors, with gender accounting for 0.6% of the variance.

Model 3’s performance metric was h-index (R2 = .16, F(4, 409) = 19.93, p < .001). As in Model 2, only year of degree (b = −.63, SE = .16, p < .001) and h-index (b = 6.77, SE = 2.48, p = .007) were significant predictors of award score. Neither institution score (b = 1.15, SE = .74, p < .13) nor gender (b = 4.1, SE = 2.83, p < .15) were significant predictors of award score.

To further examine the role of gender and the other variables in Models 2 and 3 we conducted four mediation analyses. The first two tested whether citations and h-index mediated the effect of gender on award score. The final two tested whether award score mediated the effect of gender on citations and h-index. Both could be true, to different degrees.

We tested both models using the PROCESS macro of SPSS version 24.0, developed by Hayes (2017). The PROCESS macro estimates effects with bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals that are significant when the upper and lower bound of the bias corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) does not contain zero. Mediation is assessed by the indirect effect of the X (independent variable) on Y (dependent variable) through M (the mediator), which can be significant regardless of the significance of the total effect (the effect of X on Y) and the direct effect (the effect on Y when both X and M are included as predictors).

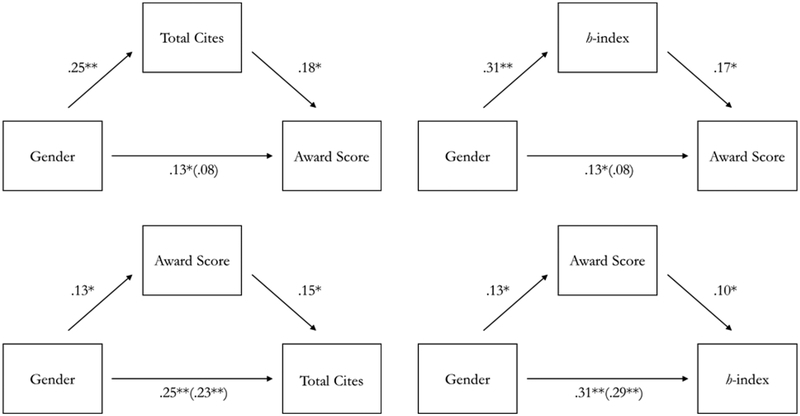

In all four mediation models, institution score and year of degree were included as covariates. Mediation Model 1, shown in the top left panel of Fig. 1, included gender as the predictor variable, award score as the outcome variable, and total cites as the mediator variable. The bias corrected bootstrap 95% CI indicated that total cites fully mediates the effect of gender on award score: the indirect effect of gender on award score through total cites was significant (b = 2.49, SE = .86, 95% CI [1.03, 4.42]), while the direct effect of gender on award score was nonsignificant (b = 4.52, SE = 2.72, 95% CI [−.83, 9.86]).

Figure 1.

h-index as a mediator of the effect of gender on award score (top panel) and award score as a mediator of the effect of gender on total cites and h-index (bottom panel). Direct effects controlling for the mediators are in parentheses. Pathways represent standardized coefficients. *p < .01, **p < .001.

Mediation Model 2, shown in the top right panel of Fig. 1, included gender as the predictor variable, award score as the outcome variable, and h-index as the mediator variable. The bias corrected bootstrap 95% CI indicated that h-index fully mediates the effect of gender on award score: the indirect effect of gender on award score through h-index was significant (b = 2.9, SE = 1.2, 95% CI [0.86, 5.59]), while the direct effect of gender on award score was nonsignificant (b = 4.1, SE = 2.83, 95% CI [−1.47, 9.67]).

Mediation Model 3, shown in the bottom left panel of Fig. 1, included gender as the predictor variable, total cites as the outcome variable, and award score as the mediator variable. The bias corrected bootstrap 95% CI indicated that award score partially mediates the effect of gender on total cites: the indirect effect of gender on total cites through award score was significant, (b = .04, SE = .02, 95% CI [.01, .10]), and the direct effect of gender on h-index was also significant (b = .52, SE = .10, 95% CI [.33, .71]).

Mediation Model 4, shown in the bottom right panel of Fig. 1, included gender as the predictor variable, h-index as the outcome variable, and award score as the mediator variable. The bias corrected bootstrap 95% CI indicated award score partially mediates the effect of gender on h-index: the indirect effect of gender on h-index through award score was significant, (b = 0.41, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.31, .51]), and the direct effect of gender on h-index was also significant (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.005, 0.04]).

Discussion

Our aim was to understand the determinants of award bestowal and the role of gender. To this end, we tested the hypothesis that gender disparities in awards to faculty in neuroscience are attributable in part to direct or indirect effects of gender schemas. Our approach was to estimate the effect of gender on award scores (i.e. the total prestige of the awards bestowed upon a researcher) while controlling for other factors that lead to award receipt: year of degree, institutional prestige, total publications, total citations, and h-index. We found that women had lower award scores than men, and that this effect remained when controlling for institutional prestige, year of degree, and total publications. Controlling for either total citations or h-index, however, eliminated the gender gap in award score.

Because gender was unrelated to award score after controlling for structural factors and (citation-based) performance metrics, our findings do not support a direct path from gender schemas to gender disparities in awards. However, our findings are consistent with an indirect path from gender schemas to gender disparities in awards: gender schemas may lead to women’s papers receiving fewer citations than men’s papers, resulting in more prestigious awards for men than for women. As previously discussed, this account is consistent with research demonstrating that women are cited less than men independent of the quality of their work and even when they publish in high-impact journals (Bendels et al, 2018; Dion et al., 2018; Larivière et al., 2013; Maliniak et al., 2013; cf. Lynn et al., 2019).

A second, non-mutually exclusive account of our findings is that they reflect a reciprocal influence between awards and citations: women’s papers may have received fewer citations in part because they received fewer awards. Consistent with this, we found that award score partially mediated the effect of gender on total cites and h-index. This finding points to a feedback loop between awards and performance: gender schemas produce gender disparities in awards (by creating gender disparities in citation and h-index), which then exacerbates gender disparities in total cites and h-index, which then exacerbates gender disparities in awards, ad infinitum. On this account, gender disparities in citations and h-index not only cause gender disparities in awards, but are also effects of gender disparities in awards.

Of course, our findings do not rule out the possibility than women’s and men’s papers differ in quality. Doing so would require an objective measure of quality, which is elusive. As we have suggested, quality does not correspond to number of citations or h-index.

A few qualifications are in order. First, from the present cross-sectional observational data it is not possible to tease apart the complex relations that hold among the variables we included. Also, our models accounted for less than 20% of the variance, suggesting that variables we did not include – such as the prestige of the nominators and the quality of nomination letters– may be important. For instance, recommendation letters for job candidates tend to overrate men (e.g., Trix & Psenka, 2003) and critiques of grant proposals are more likely to describe men than women as leaders and pioneers (Magua, et al., 2017). But awards may also simply have a large element of luck involved. Despite these caveats, the present results have a number of practical implications.

First, our findings suggest that researchers can promote gender equality in awards by being diligent in searching for and citing high-quality papers by women as well as men. Such diligence can be fostered by increasing awareness among individual researchers, and by editorial and reviewer efforts to alert authors to relevant, high-quality papers by women that they failed to cite. Second, to the extent that awards are important signals of achievement both for observers and for scholars themselves, more attention to gender equity in the distribution of awards is warranted. Interventions to consider are ensuring that women are nominated for awards in convincing nomination letters, ensuring that women are present on awards panels, and ensuring that awards panelists learn about the ways that women can be undervalued professionally.

Conclusion

Ours is one of the few studies to examine gender disparities in awards while controlling for other plausible factors that would lead to awards (see King et al, 2017). Additional research is necessary in order to reliably estimate the independent effect of gender on awards. Overall, however, the present findings are consistent with existing work showing that women in science receive fewer honors than men (Johnson et al, 2017; King et al, 2017; Lincoln et al, 2012; Nittrouer, et al, 2018; Popejoy & Leboy, 2012; Silver et al, 2018; Schroeder et al, 2013; Wennerås & Wold, 1997), and that this may result from gendered citation patterns. The present findings also provide novel directions for future research, namely, to establish the causal relationships among gender, award score, total cites, and h-index in neuroscience.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation (Award No. 0123609), the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. GM088530), and the Sloan Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

We thank Nancy Kanwisher and Paul Rozin for their helpful feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Appendix. List of awards and average award score

| American Academy of Arts and Sciences | |

| Fellow | 7 |

| American Academy of Neurology | |

| Norman Geschwind Prize in Behavioral Neurology | 4 |

| American Association for the Advancement of Science | |

| Fellow | 5 |

| Philip Hauge Abelson Award | 5 |

| Eppendorf and Science Prize for Neurobiology | 3 |

| Newcomb Cleveland Prize | 2 |

| American Neurological Association | |

| Elected member | 6 |

| American Psychological Association | |

| Fellow | 7 |

| Master Lecturer | 7 |

| Distinguished Scientific Award for Early Career Contribution to Psychology | 6 |

| D.G. Marquis Behavioral Neuroscience Award | 4 |

| Association for Psychological Science | |

| Fellow | 8 |

| James McKeen Cattell Award | 8 |

| Williams James Fellow | 8 |

| Janet T Spence Award for Transformative Early Career Contributions | 7 |

| Cognitive Neuroscience Society | |

| Distinguished Career Contributions Award | 8 |

| George A. Miller Prize | 7 |

| National Academy of Sciences | |

| Fellow | 9 |

| Troland Award | 8 |

| Nobel Prize | 9 |

| Organization for Human Brain Mapping | |

| Wiley Young Investigator Award | 3 |

| Editor’s Choice Award | 2 |

| Society of Experimental Psychologists | |

| Fellow | 5 |

| Society for Neuroscience | |

| Mika Salpeter Lifetime Achievement Award | 6 |

| Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation Neuroscience Prize | 6 |

| Young Investigator Award | 6 |

| Ralph W. Gerard Prize in Neuroscience | 5 |

| Swartz Prize for Theoretical and Computational Neuroscience | 5 |

| Jacob P. Waletzky Award | 3 |

| Janett Rosenberg Trubatch Career Development Award | 2 |

Footnotes

The authors have made available for use by others the data that underlie the analyses presented in this paper (see Melnikoff, D. (2019)), thus allowing replication and potential extensions of this work by qualified researchers. Next users are obligated to involve the data originators in their publication plans, if the originators so desire. Data Repository: https://osf.io/4jefy/.

Contributor Information

David E. Melnikoff, Yale University

Virginia V. Valian, Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center

References

- Azoulay P, Stuart T, & Wang Y (2013). Matthew: Effect or fable?. Management Science, 60(1), 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bendels MH, Müller R, Brueggmann D, & Groneberg DA (2018). Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by Nature Index journals. PloS one, 13(1), e0189136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann L, Schier H, Marx W, & Daniel HD (2012). What factors determine citation counts of publications in chemistry besides their quality?. Journal of Informetrics, 6(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brashears ME, Hoagland E, & Quintane E (2016). Sex and network recall accuracy. Social Networks, 44, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, & Handelsman J (2014). The presence of female conveners correlates with a higher proportion of female speakers at scientific symposia. MBio, 5(1), e00846–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duch J, Zeng XHT, Sales-Pardo M, Radicchi F, Otis S, Woodruff TK, & Amaral LAN (2012). The possible role of resource requirements and academic career-choice risk on gender differences in publication rate and impact. PloS one, 7(12), e51332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci L, Balsis S, & Busch AJB (2015). Gender and the h index in psychology. Scientometrics, 105(3), 2023–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Harzing AW (2007). Publish or Perish, available from http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm.

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman ME (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657–674. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman ME, Manzi F, & Braun S (2015). Presumed incompetent: perceived lack of fit and gender bias in recruitment and selection In Broadbridge AM & Fielden SL (Eds.), Handbook of gendered careers in management: getting in, getting on, getting out (pp. 90–104). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS, Smith PK, & Wang C (2017). Sage on the stage: Women’s representation at an academic conference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KP, Arena DF, Nittrouer CL, Alonso NM, & Lindsey AP (2017). Subtle discrimination in the workplace: A vicious cycle. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10(1), 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- King JJ, Angoff NR, Forrest JJ, & Justice AC (2017). Gender disparities in medical student research awards: A thirteen-year study from the Yale School of Medicine. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MM, Bergstrom CT, Correll SJ, Jacquet J, & West JD (2017). Men set their own cites high: Gender and self-citation across fields and over time. Socius, 3, 2378023117738903. [Google Scholar]

- Klein RS, Voskuhl R, Segal BM, Dittel BN, Lane TE, Bethea JR, … & Piccio L (2017). Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nature Immunology, 18(5), 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larivière V, Ni C, Gingras Y, Cronin B, & Sugimoto CR (2013). Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science. Nature News, 504(7479), 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln AE, Pincus S, Koster JB, & Leboy PS (2012). The Matilda Effect in science: Awards and prizes in the US, 1990s and 2000s. Social Studies of Science, 42(2), 307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn FB, Noonan MC, Sauder M, & Andersson MA (2019). A rare case of gender parity in academia. Social Forces, 1–30 (online). [Google Scholar]

- MacRoberts MH, & MacRoberts BR (2018). The mismeasure of science: Citationanalysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 69(3), 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Magua W, Zhu X, Bhattacharya A, Filut A, Potvien A, Leatherberry R, … & Kaatz A (2017). Are female applicants disadvantaged in National Institutes of Health peer review? Combining algorithmic text mining and qualitative methods to detect evaluative differences in R01 reviewers’ critiques. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(5), 560–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliniak D, Powers R, & Walter BF (2013). The gender citation gap in international relations. International Organization, 67(4), 889–922. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikoff D (2019). Awards in Neuroscience [Data set]. https://osf.io/4jefy/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nittrouer CL, Hebl MR, Ashburn-Nardo L, Trump-Steele RC, Lane DM, & Valian V (2018). Gender disparities in colloquium speakers at top universities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(1), 104–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara K, Kuvaeva A, Nyunt G, Waugaman C, & Jackson R (2017). Asked more often: Gender differences in faculty workload in research universities and the work interactions that shape them. American Educational Research Journal, 54(6), 1154–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström U, & Hällsten M (2008). Persistent nepotism in peer-review. Scientometrics, 74(2), 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Sardelis S, & Drew JA (2016). Not “pulling up the ladder”: women who organize conference symposia provide greater opportunities for women to speak at conservation conferences. PloS one, 11(7), e0160015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J, Dugdale HL, Radersma R, Hinsch M, Buehler DM, Saul J, … & Santure AW (2013). Fewer invited talks by women in evolutionary biology symposia. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 26(9), 2063–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShanghaiRankings Consultancy. (2011). Academic Ranking of World Universities – 2011. Academic Ranking of World Universities Since 2003; 02/29/2012. http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2011.html [Google Scholar]

- Silver JK, Blauwet CA, Bhatnagar S, Slocum CS, Tenforde AS, Schneider JC, … & Mazwi NL (2018). Women physicians are underrepresented in recognition awards from the Association of Academic Physiatrists. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 97(1), 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ & Valian V (2018). An inclusive academy: Achieving diversity and excellence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trix F, & Psenka C (2003). Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse & Society, 14(2), 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- van Arensbergen P, van der Weijden I, & Van den Besselaar P (2012). Gender differences in scientific productivity: a persisting phenomenon?. Scientometrics, 93(3), 857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerås C & Wold A (1997). Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature, 387, 341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, & Shauman KA (1998). Sex differences in research productivity: New evidence about an old puzzle. American Sociological Review, 63(6), 847–870. [Google Scholar]