Conflicting data exist about the impact of antibiotic exposure on clinical outcome during immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (aNSCLC). Routy et al. [1] and Derosa et al. [2] described a detrimental effect of antibiotic administration on clinical outcome during ICB in aNSCLC, which is in line with our single-center experience at the tertiary cancer center in Salzburg [3]. Derosa et al. reported an inferior median overall survival (mOS) associated with the use of antibiotics within a time frame of 30 days [hazard ratio (HR) = 4.4] or 60 days (HR = 2.0) preceding ICB initiation in 239 patients with aNSCLC [2]. In contrast, Metges et al. found a survival advantage for patients receiving antibiotics up to 60 days before or during ICB (mOS: 16.2 versus 11.5 months, P = 0.01) in 325 aNSCLC patients [4].

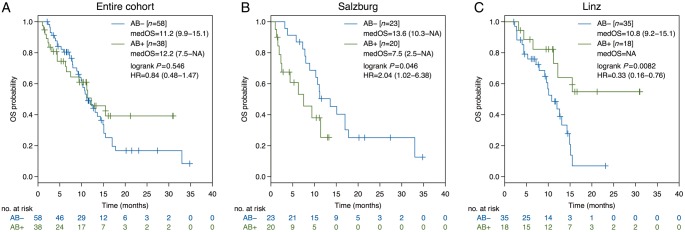

In our bi-centric analysis, including 96 non-squamous aNSCLC patients, no influence of antibiotic exposure on mOS from ICB initiation was found (AB--group: 11.2 versus AB+-group: 12.2 months, HR = 0.84, P = 0.546, Figure 1A). In contrast to Derosa et al. and Metges et al., the defined time frame of antibiotic exposure ranged from one month before to 1 month after ICB start in our analysis. Neither the time point of antibiotic administration (before: 15.5 months, after: 6.3 months, before and after: not reached, P = 0.060), nor a distinct antibiotic class applied as monotherapy (P = 0.954) was associated with mOS.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival according to the antibiotic treatment status. Comparison of Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival between antibiotic-positive and antibiotic-negative group in advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer for the entire cohort (A), for the tertiary cancer center in Salzburg (B) and for the tertiary cancer center in Linz (C). The 95% confidence interval is shown in brackets. Tick marks represent censored patients. medOS, median overall survival; HR, hazard ratio.

While the detrimental effect of antibiotic exposure on clinical outcome with ICB was corroborated in our aNSCLC cohort in Salzburg (N = 43, AB--group: mOS 13.6 versus AB+-group: 7.5 months, HR = 2.04, P = 0.046, Figure 1B) [3], an opposite effect was found at the tertiary cancer center in Linz (N = 53; AB--group: mOS 10.8 months versus AB+-group: not reached, HR = 0.33, P = 0.008, Figure 1C). The imbalance of ECOG performance status (PS) at the time point of ICB initiation between the centers in Salzburg and Linz (ECOG PS ≥2: 30% versus 0%, P < 0.001, supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) might have laid the basis for a confounding bias. It is noteworthy that ECOG PS in our bicentric AB+-group was worse in comparison to the Derosa study (ECOG PS ≥2: 13% versus 1%). However, the antibiotic treatment status and ECOG PS remained independently associated with mOS in multivariate analysis in the latter study [2]. Compared with Derosa et al. (20% within 30 days, 28% within 60 days) and Metges et al. (47% within 60 days), 40% of patients had been exposed to antibiotics in our cohort predominantly as empiric antibiotic therapy and for upper respiratory tract infections.

Despite the high clinical interest in this topic, only a few retrospective studies have reported an inferior outcome with antibiotics use during ICB and the question arises whether a publication bias exists. In consideration of the limited and conflicting data and due to putative heterogeneity between tertiary cancer centers as depicted in our bi-centric approach, prospective stratification according to the antibiotic treatment status is necessitated in future clinical trials to clarify the impact of antibiotic administration on clinical outcome with ICB.

Supplementary Material

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

FH received travel grants from BMS, Roche and MSD. GR has acted as scientific advisor for Roche, obtained speakers’ honoraria from BMS and Roche, received travel grants from Roche and received research funding from Roche. DL received travel grants from Roche. BL has acted as scientific advisor for, or obtained speakers’ honoraria from BMS, MSD, and Roche. RG received speakers’ honoraria from Roche, Merck/MSD and BMS, has acted as scientific advisor for Roche and BMS, received research funding from Roche, Merck/MSD and BMS, and obtained travel grants from Roche. HH has declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L. et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2017; 359(6371): 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M. et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(6): 1437–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huemer F, Rinnerthaler G, Westphal T. et al. Impact of antibiotic treatment on immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy in advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2018; 9(23): 16512–16520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Metges J, Michaud E, Lagadec DD. et al. Impact of anti-infectious and corticosteroids on immunotherapy: nivolumab and pembrolizumab follow-up in a French study. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(Suppl 8): viii400–viii441. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.