To the Editor

Recently, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) are frequently used to treat patients with type 2 diabetes. We previously reported that SGLT2is improve liver function in addition to lowering plasma glucose [1, 2]. Hepatic histological improvement by SGLT2is was also observed. SGLT2is reduced scores of steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning, and fibrosis stage by 78%, 33%, 22%, and 33% at 24 weeks compared to the pretreatment, respectively [3]. Reduction of body weight and insulin resistance by SGLT2is may be largely associated with an improvement of liver function [4]. However, we have not fully understood the potential SGLT2i-induced mechanisms for an improvement of liver. Therefore, we discussed the possible underlying mechanisms for an improvement of liver function due to SGLT2is by reviewing literatures.

Reported mechanisms for an improvement of liver function due to SGLT2is are shown in Table 1 [5-13]. Four-week repeated administration of ipragliflozin improved not only hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia but also hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet and streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced type 2 diabetic mice [5]. In addition, ipragliflozin reduced plasma and liver levels of oxidative stress biomarkers and inflammatory markers, and improved liver injury [5]. Repeated administration of ipragliflozin to streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats for 4 weeks significantly improved hepatic steatosis and reduced liver levels of oxidative stress biomarkers and plasma levels of inflammatory markers, and improved liver injury [6]. The effect of ipragliflozin on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in rats fed a choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined (CDAA) diet was reported [7]. Five weeks after starting the CDAA diet, rats exhibited hepatic triglyceride (TG) accumulation, fibrosis, and mild inflammation. Repeated administration of ipragliflozin prevented hepatic TG accumulation, large lipid droplet formation and liver fibrosis. Ipragliflozin also improved hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-induced and leptin-deficient obese (ob/ob) mice irrespective of body weight reduction [8]. Ipragliflozin-induced hyperphagia occurred to increase energy intake, attenuating body weight reduction with increased epididymal fat mass. However, there is an inverse correlation between weights of liver and epididymal fat in ipragliflozin-treated obese mice, suggesting that ipragliflozin promoted normotopic fat accumulation in the epididymal fat and prevented ectopic fat accumulation in the liver. Such an effect of SGLT2is on hepatic fat accumulation was also reported in humans. Luseogliflozin was reported to reduce magnetic resonance imaging-hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetes patients with NAFLD [9, 10]. Very recently, empagliflozin effectively lowered liver fat content in well-controlled type 2 diabetic patients [11]. In this study, empagliflozin raised adiponectin levels [11], which has beneficial effects on glucose and lipid metabolism including activation of adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [14].

Table 1. Reported Mechanisms for an Improvement of Liver Function due to SGLT2is.

| SGLT2is | References | Subjects | Effects on liver and putative mechanisms to improve liver function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ipragliflozin | [5] | Type 2 diabetic mice | Improvement of hepatic steatosis and liver injury; reduction of plasma and liver levels of oxidative stress biomarkers and inflammatory markers |

| Ipragliflozin | [6] | Type 1 diabetic rats | Improvement of hepatic steatosis and liver injury; reduction of liver levels of oxidative stress biomarkers and plasma levels of inflammatory markers |

| Ipragliflozin | [7] | NAFLD rats | Prevention of hepatic triglyceride accumulation, large lipid droplet formation and liver fibrosis |

| Ipragliflozin | [8] | Obese mice | Prevention of ectopic fat accumulation in the liver |

| Luseogliflozin | [9, 10] | Type 2 diabetic patients with NAFLD | Reduction of hepatic fat content |

| Empagliflozin | [11] | Well-controlled type 2 diabetic patients | Lowering of liver fat content |

| Canagliflozin | [12] | HEK-293 cells | AMPK activation by inhibition of Complex I of the respiratory chain; inhibition of lipid synthesis, by phosphorylation of ACC at the AMPK sites in human hepatocytes, which leads to downregulation of fatty acid synthesis-related molecules and upregulation of β oxidation-associated molecules |

| Tofogliflozin | [13] | C57BL/6 mice | Decrease of hepatic triglyceride content; acceleration of lipolysis in adipose tissue and hepatic β-oxidation |

SGLT2is: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; ACC: acetyl-CoA carboxylase; AMPK: adenosine 5'-monophosphate-activated protein kinase; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HEK: human embryonic kidney.

AMPK activation was also induced by canagliflozin, which was caused by inhibition of Complex I of the respiratory chain, leading to increases in cellular AMP or adenosine diphosphate (ADP) [12]. Canagliflozin inhibited lipid synthesis, an effect that was absent in AMPK knockout cells and that required phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) at the AMPK sites [12]. Another study also showed that SGLT2is ameliorated fat deposition and increased AMPK phosphorylation, resulting in phosphorylation of its major downstream target, ACC, in human hepatocytes, which led to the downregulation of downstream fatty acid (FA) synthesis-related molecules and the upregulation of downstream β oxidation-associated molecules [15]. Tofogliflozin reduced the body weight gain, mainly because of fat mass reduction associated with a diminished adipocyte size in C57BL/6 mice [13]. Serum-free FA and ketone bodies were increased and the respiratory quotient was decreased in the tofogliflozin-treated mice, suggesting the acceleration of lipolysis in adipose tissue and hepatic β-oxidation [13]. Hepatic TG contents were decreased. Further, tofogliflozin ameliorates insulin resistance and obesity by increasing glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and lipolysis in adipose tissue.

Empagliflozin shifted energy metabolism towards fat utilization, elevated AMPK and ACC phosphorylation in skeletal muscle in diet-induced obese mice [16]. SGLT2is induce a negative energy balance state by excreting glucose in the urine, which may induce alteration in glucose-FA cycle [17]. The fundamental concept of glucose-FA cycle is reciprocal substrate competition between glucose and FA in oxidative tissues such as skeletal muscles. By now, many new mechanisms controlling the utilization of glucose and FA have been discovered [18]. Dysregulation of FA metabolism is a key event responsible for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [19]. We speculate that SGLT2i-mediated alteration of glucose-FA cycle may induce changes in glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and liver, which may be associated with amelioration of liver function.

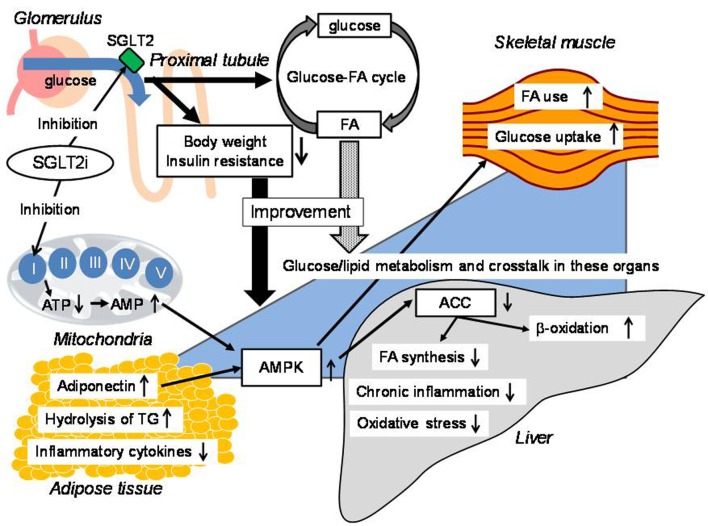

In conclusion, the summary of possible underlying mechanisms for an improvement of liver function due to SGLT2is is shown in Figure 1. SGLT2is lead to reduction of renal glucose reabsorption and decrease of plasma glucose in an insulin-independent manner, inducing reduction of body weight and insulin resistance, which may be largely associated with an improvement of liver function. Increased renal excretion of glucose may alter glucose-FA cycle and may result in increase of FA use/oxidation in skeletal muscle and liver, and increase of lipolysis in adipose tissue. The improvement of insulin resistance and altered glucose-FA cycle may ameliorate glucose/lipid metabolic crosstalk between skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and liver, which may also contribute to an improvement of liver function. SGLT2is also induce activation of AMPK, which increases FA use/oxidation in skeletal muscle and liver, and decreases FA synthesis in liver. Decrease of hepatic fat accumulation by SGLT2is reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, which may induce amelioration of liver function.

Figure 1.

The possible underlying mechanisms for an improvement of liver function due to SGLT2is. ACC: acetyl-CoA carboxylase; AMPK: adenosine 5'-monophosphate-activated protein kinase; FA: fatty acid; SGLT2is: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; TG: triglyceride; AMP: adenosine 5'-monophosphate; ATP: adenosine triphosphate.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff (Yukie Kawamura, Keiko Nakamura, Harue Aoki and Ayano Sakakibara) of the Division of Research Support, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Kohnodai Hospital.

Financial Disclosure

Authors have no financial disclosure to report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning this article.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

HY designed the research, and MH and HK collected and analyzed data. HY wrote and approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Katsuyama H, Hamasaki H, Adachi H, Moriyama S, Kawaguchi A, Sako A, Mishima S. et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes: a chart-based analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(3):237–243. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2467w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanai H, Hakoshima M, Adachi H, Kawaguchi A, Waragai Y, Harigae T, Masui Y. et al. Effects of six kinds of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on metabolic parameters, and summarized effect and its correlations with baseline data. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(7):605–612. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3046w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akuta N, Kawamura Y, Watanabe C, Nishimura A, Okubo M, Mori Y, Fujiyama S. et al. Impact of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor on histological features and glucose metabolism of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease complicated by diabetes mellitus. Hepatol Res. 2019;49(5):531–539. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanai H, Katsuyama H, Hamasaki H, Adachi H, Moriyama S, Yoshikawa R, Sako A. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: possible anti-atherosclerotic effects beyond glucose lowering. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(1):10–14. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2385w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tahara A, Kurosaki E, Yokono M, Yamajuku D, Kihara R, Hayashizaki Y, Takasu T. et al. Effects of SGLT2 selective inhibitor ipragliflozin on hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and obesity in type 2 diabetic mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;715(1-3):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tahara A, Kurosaki E, Yokono M, Yamajuku D, Kihara R, Hayashizaki Y, Takasu T. et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 selective inhibitor ipragliflozin on hyperglycaemia, oxidative stress, inflammation and liver injury in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66(7):975–987. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashizaki-Someya Y, Kurosaki E, Takasu T, Mitori H, Yamazaki S, Koide K, Takakura S. Ipragliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, exhibits a prophylactic effect on hepatic steatosis and fibrosis induced by choline-deficient l-amino acid-defined diet in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;754:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komiya C, Tsuchiya K, Shiba K, Miyachi Y, Furuke S, Shimazu N, Yamaguchi S. et al. Ipragliflozin improves hepatic steatosis in obese mice and liver dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients irrespective of body weight reduction. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuchay MS, Krishan S, Mishra SK, Farooqui KJ, Singh MK, Wasir JS, Bansal B. et al. Effect of empagliflozin on liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial (E-LIFT Trial) Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1801–1808. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumida Y, Murotani K, Saito M, Tamasawa A, Osonoi Y, Yoneda M, Osonoi T. Effect of luseogliflozin on hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetes patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective, single-arm trial (LEAD trial) Hepatol Res. 2019;49(1):64–71. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahl S, Gancheva S, Strassburger K, Herder C, Machann J, Katsuyama H, Kabisch S. et al. Empagliflozin effectively lowers liver fat content in well-controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, phase 4, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2019 doi: 10.2337/dc19-0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley SA, Ford RJ, Smith BK, Gowans GJ, Mancini SJ, Pitt RD, Day EA. et al. The Na+/Glucose cotransporter inhibitor canagliflozin activates AMPK by inhibiting mitochondrial function and increasing cellular AMP levels. Diabetes. 2016;65(9):2784–2794. doi: 10.2337/db16-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obata A, Kubota N, Kubota T, Iwamoto M, Sato H, Sakurai Y, Takamoto I. et al. Tofogliflozin improves insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and accelerates lipolysis in adipose tissue in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(3):1029–1042. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanai H, Yoshida H. Beneficial effects of adiponectin on glucose and lipid metabolism and atherosclerotic progression: mechanisms and perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(5):1190. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang H, Lee JC, Huang HC, Huang H, Liu HK, Huang C. Delayed intervention with a novel SGLT2 inhibitor NGI001 suppresses diet-induced metabolic dysfunction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2019 doi: 10.1111/bph.14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, Nagata N, Nagashimada M, Zhuge F, Ni Y, Chen G, Mayoux E. et al. SGLT2 inhibition by empagliflozin promotes fat utilization and browning and attenuates inflammation and insulin resistance by polarizing M2 macrophages in diet-induced obese mice. EBioMedicine. 2017;20:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1963;1(7285):785–789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(63)91500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(3):E578–591. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00093.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delarue J, Magnan C. Free fatty acids and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10(2):142–148. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328042ba90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]