Abstract

Unfavorable pregnancy outcomes caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) or Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infection are well known. The first step in addressing antenatal CT and NG infection is a national policy to screen all pregnant women for CT and NG, regardless of symptoms. The aim of this study was to inform policy makers on the presence of antenatal screening recommendations for CT and NG infection. We conducted a two-part survey from June 2015-February 2016. We analyzed English language information online on Ministry of Health websites regarding CT/NG antenatal screening. We contacted the Ministry of Health directly if the information on the national antenatal screening was outdated or unavailable. In parallel, we sent a survey to the regional representative from the World Health Organization (WHO) to help collect country-level data. Finally, we referenced primary country or regional policy documents. Fourteen countries have current policies for antenatal screening of CT and/or NG infection: Australia, the Bahamas, Bulgaria, Canada, Estonia, Japan, Germany, Latvia, New Zealand, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Romania, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. Australia, New Zealand, Latvia and the United States restricted antenatal screening to women ≤25 years old and those of higher risk. Several countries responded that they had policies to screen pregnant women with symptoms. This is the currently recommended WHO guideline but is not the same as universal screening. North Korea had policies in place which were not implemented due to lack of personnel and/or supplies. National level policies to support routine screening for CT and NG infection to prevent adverse pregnancy and newborn outcomes are uncommon.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a significant public health concern with more than 1 million people acquiring an STI every day worldwide (1,2). The most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection is Chlamydia Trachomatis (CT) with an estimated 131 million new cases each year (1). CT and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae (NG) infections are often asymptomatic, especially in women (4). The syndromic approach to CT and NG management currently recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) may therefore be ineffective (4, 5). This approach uses the identification of symptoms and signs that are recognizable and consistent such as vaginal discharge and lower abdominal pain as a basis for CT and NG treatment (1, 6). However, only 5–30% of women with laboratory-confirmed CT and NG infection develop symptoms (7). An alternative approach that screens all pregnant women regardless of symptoms might be beneficial when considering the extensive adverse pregnancy and newborn health outcomes that are linked to both CT and NG (8,9).

Unfavorable pregnancy outcomes caused by CT and NG infection include spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight (LBW) and postpartum endometritis (3,8,10,11). Those adverse outcomes may be particularly perilous for newborns in resource constrained areas of the developing world (8,12). Clinical screening may be very important for early eradication of infection which may reduce preterm birth by reducing exposure to these pathogenic during pregnancy (24).

Untreated CT can also increase the likelihood of HIV transmission from a mother to her infant (7, 13, 40). In addition, perinatal transmission of CT or NG can cause neonatal opthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis) and pneumonia (7,14,15,16). Worldwide, up to 4,000 newborn babies become blind every year because of eye infections attributable to untreated maternal CT and NG infections (1). Effective means of preventing conjunctivitis and newborn blindness include screening all pregnant women for both CT and NG infection, and subsequently treating pregnant women and their partners for these infections (9).

Studies in several regions have demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of antenatal screening for CT and NG infection including: Australia (17), Europe (17), Latin America (18) and the Middle East (19). Another study demonstrated that antenatal CT screening of women aged 16 to 25 years was cost-effective in Australia, even with a low estimated prevalence of 3% (13, 20).

The aim of this study was to inform public health officials of the presence of current national policies on antenatal CT and NG screening by country. Our study built on the available literature on the topic, and supports updated national, regional and global recommendations of policies for antenatal CT and NG screening and treatment.

Methods

We conducted a three-part survey from June of 2015 to February 2016. Firstly, we analyzed available data online on select English-language Ministry of Health websites regarding STI screening for pregnant women. Search terms included antenatal and prenatal Ministry of Health guidelines, recommendations, CT and NG antenatal screening, STI management, antenatal visit recommendations and policies for each respective country. Google was used as the primary search engine. Primary source documents other than MOH documents were accepted such as those provided from national health protection bodies like the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. If data was available online, the country MOH was not contacted unless online information was ambiguous in order to receive secondary confirmation of results. Secondly, we contacted the country’s Minister of Health when official screening recommendations for a country were not available online. Ministries of Health were contacted to ascertain whether they had a national CT and NG antenatal screening policy in place or not. Contact was sent via email in English, French and Spanish. Contact to countries with different languages were constructed to the best of the researcher’s ability.

Thirdly, we contacted the reproductive health representative for each WHO region and requested them to assist us in collecting country level data on screening practices among pregnant women for both CT and NG. Our survey consisted of an introduction to the 3-question survey followed by an inquiry about that country’s policy on antenatal screening for CT and NG. The survey questions asked if the respective country had a government policy to provide CT and NG antenatal screening, and if yes, if screening was contingent upon any conditional criteria (i.e. <25 years of age, etc.)

WHO regions include Africa (47 countries), the Americas (35 countries), the Eastern Mediterranean (21 countries), Europe (53 countries), South-East Asia (11 countries), and the Western Pacific (27 countries).

Results

Of all 196 countries worldwide, we identified primary Ministry of Health or other primary sources of data on antenatal CT or NG screening policies for 28 countries. For the first round of surveys, we contacted an additional 98 country Ministries of Health, from which we received responses from 16 countries. 5 of the 16 responses recommended other sources for screening policy information. For the second round of surveys with the WHO regional offices, we received 20 country responses from WHO representatives, which included three additional countries that have national recommendations for antenatal CT or NG screening (Table 1). In total, we received 64 responses (including primary sourced documents) of which 14 countries reported to have antenatal CT or NG screening policies, and 43 countries reported to not have antenatal CT or NG screening policies, while 139 countries remain unknown (Table 2).

Table 1:

Policies for national antenatal screening of Chlamydia trachomatis

| No (n= 43) | Yes (n= 10) | Yes with specific criteria (n=3) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Cuba, Cyprus, Denmark, Egypt, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Malaysia, Maldives, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Norway, Panama, Philippines, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Singapore, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Thailand, Timor-Leste, UK, Uganda, Zambia | The Bahamas, Bulgaria, Canada, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Estonia, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Romania, Sweden, the United States | Australia1, Latvia2, United States3 |

<25 years of age and in areas where CT prevalence is high

pregnant women up to the age of 24, pregnant women of “social risk group”, pregnant women with sexually transmitted infection in anamnesis or clinical symptoms

Sexually active women under 25 years of age and sexually active women aged 25 years and older if at increased risk

Table 2:

Policies for national antenatal screening of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

| No (n= 41) | Yes (n= 6) | Yes with specific criteria (n=2) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Cuba, Cyprus, Denmark, Egypt, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Latvia, Malaysia, Maldives, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Panama, Philippines, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Singapore, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Uganda, Zambia | The Bahamas, Canada, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Germany, UK the United States | Australia1, New Zealand2, United States3 |

includes known risk factors or who live in or comes from areas where prevalence is high

includes <25 years of age, where no previous testing has been done in current relationship, in patients with partner change within previous 6-months or during pregnancy, in the presence of symptoms, and in patients with a history of previous NG infection.

Sexually active women under 25 years of age and sexually active women aged 25 years and older if at increased risk

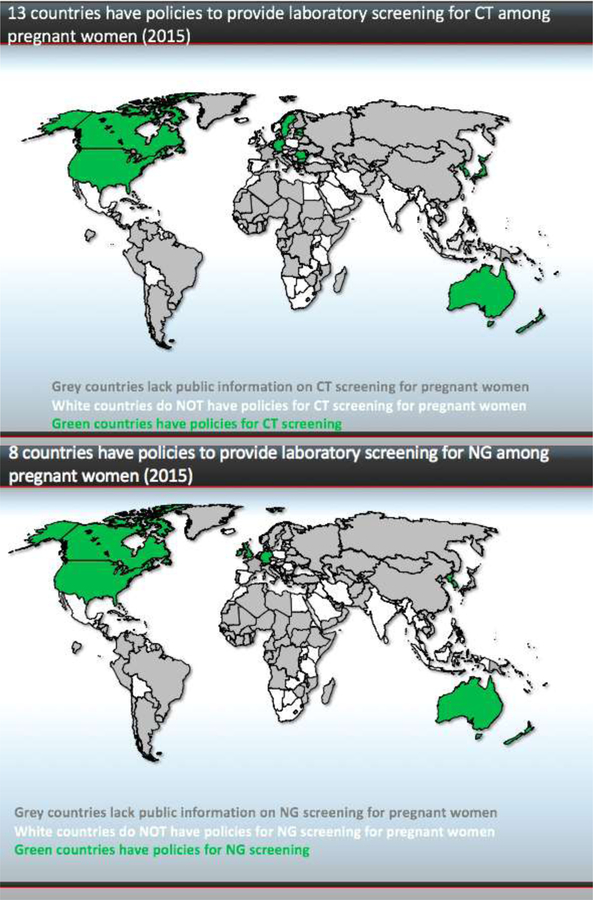

Our study found that fourteen countries have policies for antenatal screening of CT and/or NG infection: Australia, the Bahamas, Bulgaria, Canada, Estonia, Japan, Germany, Latvia, New Zealand, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Romania, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 1). Of those countries, several restrict CT and NG antenatal screening to young women ≤25 years of age, including Australia, the United States, New Zealand and Latvia. Several countries responded that they have policies to treat pregnant women with symptoms, consistent with current WHO guidelines for syndromic management. North Korea had screening policies in place which were not implemented due to lack of personnel or supplies.

Figure 1.

(a) Thirteen countries have policies to provide laboratory screening for CT among pregnant women (2015). (b) Eight countries have policies to provide laboratory screening for NG among pregnant women (2015).

Discussion

This study informs public health officials of the presence of current national policies on antenatal CT and NG screening by country and found that antenatal CT and NG screening policies were uncommon. Three of the fourteen countries with antenatal screening policies only test young women specifically (≤25 years old). Further, having a national policy does not translate into providing testing to all pregnant women. For example, many women are still not tested for CT and NG infection despite screening recommendations in the US (22,23) and New Zealand (24). Increasing the coverage of antenatal screening for CT and NG infection could greatly improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

Previous studies have confirmed the importance of improving interventions to screen and treat CT and NG in early pregnancy (25–27). Other studies demonstrated that routine antenatal CT and NG screening is the most effective intervention to prevent eye infections and pneumonia among newborns (9). Previous studies have also indicated that antenatal CT screening can be both cost-effective and highly acceptable in various global settings (19, 21, 28, 17), especially in areas with high CT prevalence (29).

Recent research has shown a persistent high prevalence of antenatal CT in different settings worldwide especially in low and middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa (11, 34), and Pacific Island countries (30). Screening pregnant women for CT has been recommended as a result of studies analyzing antenatal CT prevalence in different settings. Antenatal CT prevalence studies worldwide have demonstrated high prevalence within specific populations in Botswana (8%) (26), Cameroon (38.4% in HIV-infected patients and 7.1% in HIV-uninfected patients) (31), China (10.1%) (27), Kenya (6%) (32); Mozambique (8%) (33), Papua New Guinea (11.1%) (34), Peru (10%) (19), Saudi Arabia (10.5%) (20) South Africa (17.8%) (35) and Tanzania (11.4%) (36).

Integrating antenatal CT and NG screening can help identify curable infections among pregnant women, and sequelae among newborns. With the advent of highly sensitive and specific nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) and point of care testing platforms, implementation of routine screening in ANC in resource limited countries is warranted (32, 37,38). Clinical trials, such as the one trial ongoing in Papua New Guinea, are recommended to evaluate context-specific cost-benefit of CT and NG routine screening in ANC in different settings (39).

One barrier to future policy changes and implementation of routine screening is the inconsistent evidence basis for CT and NG screening that currently exists even within countries themselves. For example, in the US, while the U.S Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) only promotes screening for women under 24 or above 25 that are high risk, other influential US sources such as the American College of Preventative Medicine (ACPM) recommend screening all pregnant women. Thus, collaboration is needed between country-level influential organizations to consolidate a consistent evidence basis for CT and NG screening recommendations.

One limitation to our study was the large proportion of Ministries of Health and WHO representatives who did not respond to our survey. A second limitation to our study was language barriers that were encountered when reaching out to various Ministries of Health. Because of the various challenges faced in collecting the aforementioned data, we may have excluded countries with antenatal CT or NG screening policies; however, we hypothesize that the response rate was highest among countries with antenatal CT or NG screening policies. Finally, we found some discrepancy when comparing official documents with responses received from Ministries of Health. In those cases, the Ministry of Health responses took priority over other sources. A large number of countries remained unknown due to both language limitations on the part of the research group. The absence of professional translators who could have helped with communication to various countries that did not speak English, French or Spanish. These countries were contacted with limited translation and could have warranted more professional translation that may have resulted in more MOH responses. Furthermore, many countries remain unknown due to internet limitations for some of the countries. For example, there was an absence or illegitimacy of MOH contact information. A final limitation to our study was the discrepancy encountered between MOH policy and primary sources of data.

Conclusion:

Universal antenatal CT or NG screening policies were uncommon. Some regions (Middle East, Central and South America) did not have any country with antenatal CT or NG screening policies, despite persistently high antenatal CT and NG prevalence. There is a need for a response from international agencies to build a more robust and comprehensive database of programs to increase routine CT or NG screening in antenatal care. There is also an urgent need to consider the indications of new CT and NG screening policies in areas where prevalence of these infections is high and where screening asymptomatic woman could have profound benefits. Considering the high prevalence of CT and NG, and the negative maternal and newborn sequelae of these infections, we recommend further implementation science to demonstrate the feasibility, acceptability, and cost-benefit of integrating screening for CT and NG infection into existing antenatal programs. The new knowledge found in our study demonstrates that screening is lacking and there should be a greater response to increase both screening and international awareness of its benefits.

APPENDIX: References for Data On CT/NG Antenatal Screening Policies:

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2014, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module II Australian Government Department of Health, Canberra

British Association of Sexual Health and HIV, Clinical Effectiveness Group. United Kingdom National Guideline for NG Testing 2012.

Department of Health Republic of South Africa. Guidelines for Maternity Care in South Africa: Third Edition. National Maternity Guidelines Committee, 2007.

Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening Recommendations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Recommendation Sources. CDC, 2015.

Egypt Ministry of Health & Population. Practice Guidelines for Family Physicians Volume 3.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Chlamydia control in Europe - a survey of Member States. Stockholm: ECDC; 2014.

Gonorrhoea Guidelines Writing Group on behalf of the New Zealand Sexual Health Society. New Zealand Guidelines for the Management of Gonorrhoea, 2014, and Response to the Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance. NZSHS, 2014.

Government of Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Basic Package of Essential Health Services for Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, 2010. \\

Government of Southern Sudan Ministry of Health. Prevention and Treatment Guidelines for Primary Health Care Units.

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health Assistant Deputyship Minister for Hospital Affairs General Directorate of Hospitals. Guidelines for Obstetrics & Gynecology. Ministry of Health, 2013. L.D. No. 1434/8837 ISBN: 978–608-8144–08

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal Care For Uncomplicated Pregnancies: Clinical guideline Published: 26 March 2008, Last Modified December, 2014.

Norwegian gynecological association. Prenatal Care: Recommendations. NFOG, 2014.

México. Secretaría de Salud. Sistema de Protección Social en Salud. Elementos conceptuales, financieros y operativos / Se- cretaría de Salud, coord. de Eduardo González Pier, Mariana Barraza Lloréns, Cristina Gutiérrez Delgado, Armando Vargas Palacios. — 2a ed. — México: FCE, Secretaría de Salud, Funda- ción Mexicana para la Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pú- blica, 2006. 312 p. : ilus. ; 27 × 21 cm — (Colec. Biblioteca de la Salud) ISBN 978–968-16–8287-3

Ministry of Health Botswana; the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI). National Guidelines for Antenatal Care and the Management of Obstetric Emergencies and Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV in Botswana. Ministry of Health Botswana, 2005.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales E Igualdad. Plan Estratégico de Prevencion y Control de la infeccion por el VIH y otras infecciones de transmision sexual 2013–2016. Sanidad, 2015

Minakami, H., et al. (2014). “Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) 2014 edition.” J Obstet Gynaecol Res 40(6): 1469–1499.

Philippines National Center for Disease Prevention and Control Department of Health. Guidelines on the Management of Sexually-Transmitted Infections (STI) In Pregnancy. 2010.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections. Retrieved February 12, 2016 from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti-its/cgsti-ldcits/section-6-4-eng.php. PHOC, 2012.

Republica De Cuba. Ministerio De Salud Publica. Plan Estratégico Nacional Para La Prevencion Y El Control De Las ITS Y El VIH/SIDA | 2014–2018. Minterio de Salud Publica, 2013.

Republic of Kenya. Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation and Ministry of Medical Services. National Guidelines for Quality Obstetrics and Perinatal Care. Division of Reproductive Health; Kenyan Republic of Kenya, 2012.

Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. Namibia Standard Treatment Guidelines First Edition. Ministry of Health and Social Services, 2011.

Republic of Zambia Ministry of Health, 2003. Integrated Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS Protocol Guidelines.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Routine Antenatal Assessment in the Absence of Pregnancy Complications. 2015.

Swiss Confederation Federal Office of Public Health. National Programme on HIV and other STI (NPHS) 2011–2017. SCFOH, 2010.

Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda Clinical Guidelines 2010: National Guidelines on Management of Common Conditions. Uganda Ministry of Health, 2010.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance on chlamydia control in Europe – 2015. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016.

References

- (1).World Health Organization. [December 2015]; [February 16, 2016]; Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) Fact Sheet. Updated. Retrieved. from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/

- (2).Newman L, et al. (2013). “Global estimates of syphilis in pregnancy and associated adverse outcomes: analysis of multinational antenatal surveillance data.” PLoS Med 10(2): e1001396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rours GI, et al. (2011). “Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy associated with preterm delivery: a population-based prospective cohort study.” Eur J Epidemiol 26(6): 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Peuchant O, et al. (2015). “Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Mycoplasma genitalium should it be integrated into routine pregnancy care in French young pregnant women?” Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 82(1): 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).McMillan HM, et al. (2006). “Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in asymptomatic women attending outpatient clinics in a large maternity hospital in Dublin, Ireland.” Sex Transm Infect 82(6): 503–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).World Health Organization, 2004. Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections Retrieved February 16, 2016 from http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2942e/2.4.html#Jh2942e

- (7).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [November 17, 2015]; [February 16, 2016]; Chlamydia- CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed) Updated. Retrieved. from http://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia-detailed.htm.

- (8).Mullick S, Watson-Jones D, Beksinska M, & Mabey D (2005). Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy: prevalence, impact on pregnancy outcomes, and approach to treatment in developing countries. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81(4), 294–302. 10.1136/sti.2002.004077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Moore DL and MacDonald NE (2015). “Preventing ophthalmia neonatorum.” Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 26(3): 122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bébéar and Barbeyrac de (2009). “Genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections ” Clin Microbiol Infect, 15 (2009), pp. 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lacey CJ and Milne JD (1984). “Preterm labour in association with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: case reports.” Br J Vener Dis 60(2): 123–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes; Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, editors. Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. 6, The Problem of Low Birth Weight.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222095/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Adachi K, et al. (2015). “Chlamydia and NG in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Infant HIV Transmission.” Sex Transm Dis 42(10): 554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(1997). “Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections--United States, 1995.” MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 46(9): 193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Brocklehurst P, Rooney G. Interventions for treating genital chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 4 Art. No.: CD000054 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Beem MO and Saxon EM (1977). “Respiratory-tract colonization and a distinctive pneumonia syndrome in infants infected with Chlamydia trachomatis.” N Engl J Med 296(6): 306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bilardi JE, et al. (2010). “Young pregnant women’s views on the acceptability of screening for chlamydia as part of routine antenatal care.” BMC Public Health 10: 505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cabeza J, et al. (2015). “Feasibility of Chlamydia trachomatis screening and treatment in pregnant women in Lima, Peru: a prospective study in two large urban hospitals.” Sex Transm Infect 91(1): 7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Alzahrani AJ, et al. (2010). “Screening of pregnant women attending the antenatal care clinic of a tertiary hospital in eastern Saudi Arabia for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections.” Indian J Sex Transm Dis 31(2): 81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Ong JJ, et al. (2015). “Chlamydia screening for pregnant women aged 16–25 years attending an antenatal service: a cost-effectiveness study.” Bjog [DOI] [PubMed]

- (21).Blatt et al. , 2010. Blatt AJ, Lieberman JM, Hoover DR, and Kaufman HW: Chlamydial and gonococcal testing during pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 207: pp. 55.e1–55.e18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fontenot HB and George ER (2014). “Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy.” Nurs Womens Health 18(1): 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wise MR, et al. (2015). “Chlamydia trachomatis screening in pregnancy in New Zealand: translation of national guidelines into practice.” J Prim Health Care 7(1): 65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Folger AT (2014). “Maternal Chlamydia trachomatis infections and preterm birth:the impact of early detection and eradication during pregnancy.” Matern Child Health J 18(8): 1795–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Romoren M, et al. (2007). “Chlamydia and gonorrhoea in pregnant Batswana women: time to discard the syndromic approach?” BMC Infect Dis 7: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chen XS, et al. (2006). “Sexually transmitted infections among pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic in Fuzhou, China.” Sex Transm Dis 33(5): 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Paavonen J, Puolakkainen M, Paukku M, and Sintonen H. 1998. Cost-benefit analysis of first-void urine Chlamydia trachomatis screening program. Obstet. Gynecol 92:292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Genc M, Mardh P. A Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Screening and Treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis Infection in Asymptomatic Women. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_Part_1-199601010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gottlieb SL, et al. (2014). “Toward global prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the need for STI vaccines.” Vaccine 32(14): 1527–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Mbu ER, et al. (2008). “Gynaecological morbidity among HIV positive pregnant women in Cameroon.” Reprod Health 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kohli R, et al. (2013). “Prevalence of genital Chlamydia infection in urban women of reproductive age, Nairobi, Kenya.” BMC Res Notes 6: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Menendez C, et al. (2010). “Prevalence and risk factors of sexually transmitted infections and cervical neoplasia in women from a rural area of southern Mozambique.” Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (33).Wangnapi RA, et al. (2015). “Prevalence and risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis infection in pregnant women in Papua New Guinea.” Sex Transm Infect 91(3): 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Moodley D, et al. (2015). “High prevalence and incidence of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections during pregnancy and postdelivery in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa.” Sex Transm Dis 42(1): 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hokororo A, et al. (2015). “High prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in pregnant adolescent girls in Tanzania: a multi-community cross-sectional study.” Sex Transm Infect 91(7): 473–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Joseph-Davey DL et al. (2016). “Prevalence of curable sexually transmitted infections in pregnant women in low- and middle-income countries from 2010–2015: A systematic review” STD, In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (37).Mahilum-Tapay L, Laitila V, Wawrzyniak JJ, Lee HH, Alexander S, Ison C, … Goh BT (2007). New point of care Chlamydia Rapid Test—bridging the gap between diagnosis and treatment: performance evaluation study. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 335(7631), 1190–1194. 10.1136/bmj.39402.463854.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Postma MJ, Bakker A, Welte R, et al. 2000. [Screening for asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatisinfection in pregnancy; cost-effectiveness favorable at a minimum prevalence rate of 3% or more.] Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd 144:2350–2354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wheelahan Dan, 2015. Sexual Health Study in PNG set to improve maternal and newborn health. The Kirby Institute at UNSW and PNGIMR Retrieved March 15, 2016 from http://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/health/sexual-health-study-png-set-improve-maternal-and-newborn-health

- (40).Ghys PD, Fransen K, Diallo MO, et al. The associations between cervicovaginal HIV shedding, sexually transmitted diseases and immunosuppression in female sex workers in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. AIDS 1997; 11: F85–F93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]