Abstract

The ideal of scientific progress is that we accumulate measurements and integrate these into theory, but recent discussion of replicability issues has cast doubt on whether psychological research conforms to this model. Developmental research—especially with infant participants—also has discipline-specific replicability challenges, including small samples and limited measurement methods. Inspired by collaborative replication efforts in cognitive and social psychology, we describe a proposal for assessing and promoting replicability in infancy research: large-scale, multi-laboratory replication efforts aiming for a more precise understanding of key developmental phenomena. The ManyBabies project, our instantiation of this proposal, will not only help us estimate how robust and replicable these phenomena are, but also gain new theoretical insights into how they vary across ages, linguistic communities, and measurement methods. This project has the potential for a variety of positive outcomes, including less-biased estimates of theoretically important effects, estimates of variability that can be used for later study planning, and a series of best-practices blueprints for future infancy research.

THE “REPLICATION CRISIS” AND ITS IMPACT IN DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

What can we learn from a single study? The ideal of scientific progress is that we accumulate progressively more precise measurements and integrate these into theories whose coverage grows broader and whose predictions become more accurate (Kuhn, 1962; Popper, 1963). On this kind of model, a single study contributes to the broader enterprise by adding one set of measurements with known precision and stated limitations. Then further studies can build on this result, reusing the method and expanding its scope, adding precision, and generally contributing to a cumulative picture of a particular area of interest. Unfortunately, recent developments have cast doubt on whether research in psychology—and perhaps in other fields of inquiry as well—conforms to this model of cumulativity (Ioannidis, 2005, 2012). For example, a large-scale attempt to reproduce 100 findings from high-profile psychological journals found that fewer than half of these were successful (Open Science Collaboration (OSC), 2015; cf. Gilbert, King, Pettigrew, & Wilson, 2016; Anderson et al., 2016).

There are many hypothesized sources for failures to replicate. First, any measurement includes some amount of random noise leading to variations in the outcome even if the exact same experiment is repeated under identical conditions (as happens, for instance, in a computer simulation; Stanley & Spence, 2014). When statistical power is low (e.g., through small sample sizes) this noise is more likely to lead to spurious, non-replicable findings (Button et al., 2013). Second, psychological findings are affected by many different contextual factors, and a poor understanding of how these factors affect our ability to measure behavior—whether in the experimental task, the test population, and/or the broader setting of the experiment—can cause a failure to replicate due to lack of standardization between researchers (Brown et al., 2014). Third, a variety of “questionable research practices” can lead to improper statistical inferences. These include undisclosed analytic flexibility (“p-hacking”; Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011) as well as other practices that bias the literature, such as the failure to publish null results (Rosenthal, 1979). All of these—and other—factors add up to create a context in which published experimental findings may inspire somewhat limited confidence (Ioannidis, 2005; Smaldino & McElreath, 2016).

The research practices that limit replicability in the broader field of psychological research are present, and maybe even exacerbated, in developmental research. Developmental experiments often have low statistical power due to small sample sizes, which in turn arise from the costs and challenges associated with recruiting and testing minors. Especially for infants, consistent measurement is difficult because these participants have short attention spans and exhibit a large range of variability both within and across age-groups. Further, measures must rely on a small set of largely undirected responses to stimuli (e.g., heart rate, head-turns); direct instruction and explicit feedback are not possible in infancy research. In addition, young participants may spontaneously refuse to attend or participate during an experimental session. Due to this potential “fussiness,” there are higher rates of data exclusion in developmental research than in adult psychology research; the need to specify fussiness criteria itself may also create further undisclosed analytic flexibility.

A related set of issues is tied to a general lack of methodological standardization: while many laboratories use similar methods, the precise setups vary, and there are few independent estimates of reliability or validity across laboratories (for discussion see, e.g., Benasich & Bejar, 1992; Cristia, Seidl, Singh, & Houston, 2016). Furthermore, initiatives that have incentivized replicability in other areas of psychology—preregistration, data sharing, and registered replication—have yet to become widespread in the developmental community.1 This confluence of limitations may lead to replicability issues in developmental research that are more significant than currently appreciated.

Inspired by collaborative replication efforts in cognitive and social psychology (Klein et al., 2014; OSC, 2015), here we describe a proposal for assessing and promoting replicability in infancy research: large-scale, multilaboratory replication efforts. The ManyBabies project, our instantiation of this proposal, aims to gain a more precise understanding of key developmental phenomena, by collecting data in a coordinated fashion across laboratories. These data will not only help us estimate how robust and replicable key phenomena are, but will also provide important new insights into how they vary across ages and linguistic communities, and across measurement methods. We believe this project has the potential for a variety of positive outcomes, including less-biased estimates of theoretically important effects, estimates of variability (e.g., between laboratories or populations) that can be used for planning further studies and estimating statistical power, and a series of best-practices blueprints for future infancy research. In the remainder of the paper, we describe our approach and then go on to address some of the challenges of collaborative developmental work.

COLLABORATIVE DATA COLLECTION IN INFANCY RESEARCH

The aims of the ManyBabies project are importantly different from the aims of previous replication projects such as the Reproducibility Project: Psychology (OSC, 2015), which focused on estimating the replicability of an entire scientific field. Instead, our aim is to understand why different developmental laboratories, studying the same phenomena using the same or highly similar methods, might find differences in their experimental results. To achieve this goal, we plan to conduct a series of preregistered, collaborative, multisite attempts to replicate theoretically central developmental phenomena. Thus, our approach is much more closely aligned with the “Many Labs” projects, from which we take our name. The Many Labs effort focuses on understanding variability in replication success and identifying potential moderators (e.g., Klein et al., 2014). But the effort involved in reproducing even one infant result across a large group of laboratories is substantial. To make the most of this effort and create high-value experimental data sets, we must navigate the tension between standardization across laboratories (with the goal of eliminating variability) and documentation of variability (with the goal of analyzing it).

For example, there is wide variation in experimental paradigms implemented across infant laboratories, manifest in both the paradigms that are available in a given laboratory and in how these paradigms are implemented. For practical reasons, it is not possible to use a single identical paradigm across laboratories, so in the ManyBabies 1 study described below, we will include several standard paradigms for measuring infant preferences (habituation, headturn preference, and eye-tracking). Each laboratory using a particular paradigm will be provided with a collaboratively developed protocol to minimize within-paradigm variability. Deviations from these standards within individual laboratories, where necessary, will be carefully documented.

As a second example of the tension between standardization and documentation, it is clearly impossible to standardize all aspects of the sample of infants that we recruit across sites. Instead, we will document participant-level demographics (e.g., native language, mono- versus bilingual environment, socio-economic status). In general, our approach will be to choose a relatively small set of potential laboratory- and participant-level moderators of experimental effects in each project and plan analyses that quantify variation on these variables.

In addition to those sources of variation that can be straightforwardly documented and analyzed, there will be other systematic variation across laboratories on dimensions that are more difficult to quantify, like physical laboratory space, participant pool, and experimenter interaction. One of the goals of the project is to measure the variability in effect size that emerges from such sources, which is typically difficult to separate from truly random variation. Minimally, we will be able to make precise estimates of the proportion of variance that is explained by (structured) lab-to-lab variation. With the hope of potentially exploring ultimate sources of structured between-laboratory variation, the group is discussing supplemental steps we can take to ensure high data collection standards, including the video recording and sharing of all experimental procedures (e.g., using sharing platforms like Databrary; Adolph et al., 2012) and the training of RAs and other experimenters with standard videos across sites.

Because participant exclusion criteria, preprocessing steps, and choice of statistical tests all present opportunities for analytic flexibility (and hence an inflation of false positives), we will fix these decisions ahead of time. We will use both simulated and real pilot data to establish a processing pipeline and set standards for data formatting, participant exclusion, and the myriad other decisions that must be taken in data analysis. Once analytic decisions are finalized, we will preregister our experimental protocol and analyses, freezing these confirmatory analyses (providing a model “standard operating procedure” for future analyses). This preregistration does not, however, preclude exploratory analyses, and we anticipate that these will be a significant source of new insights going forward. In this spirit, all of our methods, data, and analyses will be completely open by design. We will use new technical tools (e.g., the Open Science Framework) to share the relevant materials with collaborators and other interested parties. We hope this openness provides other unanticipated returns on our invested effort as others use and reuse our stimuli, protocols, data, and analysis code.

Having established a set of goals and an approach, our group next converged on a target case study. After an open and lively discussion with interested laboratories, we elected via majority vote to examine infants’ preference for speech directed to them (infant-directed speech, or IDS) in our first ManyBabies replication study (MB1), described below. We decided to begin with an uncontroversial and commonly replicated finding so as to provide some expectations for variability across laboratories and to provide guidelines for planning further studies. Indeed, further down the line, we hope to consider replications of a range of developmental phenomena, including both fundamental phenomena whose replicability is not in question as well as more controversial findings. We also recognize that there is no single approach to collaborative replication that will apply in all cases. For example, when attempting to replicate controversial findings, tight standardization will typically be necessary. However, attempts to assess the generalizability of a well-established finding will instead benefit from documenting variability. In sum, across many different possible targets, we believe that the collaborative approach will yield new empirical and theoretical insights.

MANYBABIES 1: THE PREFERENCE FOR INFANT-DIRECTED SPEECH

Infants’ preference for speech containing the unique characteristics of so-called IDS over adult-directed speech (ADS) has been demonstrated using a range of experimental paradigms and at a variety of ages (e.g., Cooper & Aslin, 1990; Cooper, Abraham, Berman, & Staska, 1997; Fernald & Kuhl, 1987; Hayashi, Tamekawa, & Kiritani, 2001; Newman & Hussain, 2006; Pegg, Werker, & McLeod, 1992; Werker & McLeod, 1989). Moreover, infants perform better in language tasks when IDS stimuli are used, including tasks such as detecting prosodic characteristics (Kemler Nelson, Hirsh-Pasek, Jusczyk, & Cassidy, 1989) or learning/recognizing words (e.g., Ma, Golinkoff, Houston, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2011; Singh, Nestor, Parikh, & Yull, 2009; Thiessen, Hill, & Saffran, 2005). A typical experimental operationalization of a preference for IDS is that infants will attend longer to a static visual target (e.g., a checkerboard) when looking leads to hearing IDS, as opposed to ADS (Cooper & Aslin, 1990).

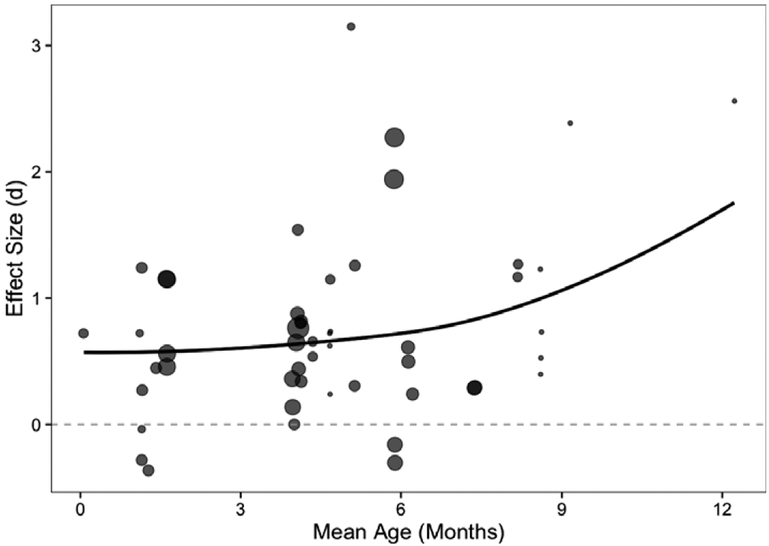

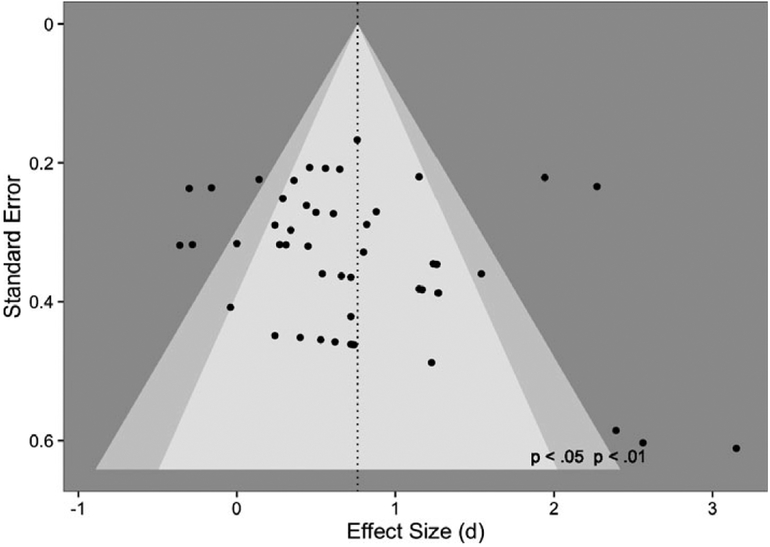

The preference for IDS is observed robustly across studies, but it is also quite variable. Data from a recent meta-analysis examining 34 published studies, including 840 infants (Dunst, Gorman, & Hamby, 2012), reveals significant heterogeneity [Q(49) > 222] and some evidence of publication bias (z = 2.5, p = .01; see Figures 1 and 2; data available at http://metalab.stanford.edu). In addition, while several moderators of the size of infants’ IDS preference have been described (e.g., age), considerable variance remains unexplained. Most notably, although the presence of IDS is a cross-linguistic phenomenon (see Soderstrom, 2007, for review), there is variation across languages, and North American English (NAE) appears to provide an especially exaggerated form (Fernald et al., 1989; Floccia et al., 2016; Kitamura, Thanavishuth, Burnham, & Luksaneeyanawin, 2002; Shute & Wheldall, 1995; although cf. Farran, Lee, Yoo, & Oller, 2016). Although studies have found preferences for IDS in other languages, including Japanese (Hayashi et al., 2001) and Chinese (Werker et al., 1994), the tendency for studies on IDS to come from North America may therefore provide an inflated view of its robustness. This description highlights why a meta-analysis is insufficient: A meta-analysis is only as good as the published body of research it rests on, and conclusions based on it are uncertain when there are biases in data collection (e.g., oversampling North American laboratories) and publication (notice that the IDS meta-analysis revealed significant bias, as low-precision studies tended to yield larger effect sizes than high-precision ones). In contrast, the collaborative approach advocated here can reduce or eliminate these sources of bias.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of infant-directed speech (IDS) preference, modified from http://metalab.stanford.edu. Points show individual studies, with point size showing N. Line shows an inverse-variance weighted local regression.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot showing the relationship between standard error and effect size for studies of infant-directed speech (IDS) preference, modified from http://metalab.stanford.edu. Individual dots represent studies. Larger and smaller funnel boundaries show 99% and 95% thresholds, respectively. Dotted line shows the mean effect size from a random-effects meta analytic model.

We selected IDS preference for our first replication study because it satisfies a number of key desiderata. Most importantly, it allows us to measure interlaboratory and interbaby variability because the effect itself is large and robust—at least within North America. With a large effect as a baseline, we can assess variation in that effect across methods (e.g., comparing eye-tracking versus human-coded procedures), across linguistic communities (e.g., comparing infants for whom the stimuli are native versus not), and across ages. Distinguishing these moderators would not be possible in the case of a phenomenon with a smaller effect size. In the worst case, if the original effect were truly null, no moderation relationships would be detectable at all.

Preference for IDS also allows MB1 to assess several questions that are important for developmental theory. First, some views of language acquisition attribute a key role to IDS preference in scaffolding language learning, due to its attentiondriving properties (e.g., Kaplan, Goldstein, Huckeby, Owren, & Cooper, 1995) or specific linguistic characteristics (e.g., Kuhl et al., 1997). Although the preference for IDS is robust with young infants, fewer studies precisely examine how this preference changes across development (although cf. Hayashi et al., 2001; Newman & Hussain, 2006). Second, our study also offers an opportunity to examine the classic theory of native-language phonological specialization—in which general preferences and perceptual abilities gradually become language-specific over the course of the first year (Kuhl, 2004; Werker & Tees, 1984)—in a new domain. Use of IDS varies across linguistic communities (see above), but there has been relatively little study of this variation. For example, as mentioned above, British English IDS has less prosodic modification than NAE IDS (Fernald et al., 1989; Shute & Wheldall, 1995). Does this imply that UK infants might be particularly interested (or uninterested) in the intonational characteristics of North American IDS? Should this interest decline as they recognize that the dialect of the IDS is distinct (Butler, Floccia, Goslin, & Panneton, 2011; Nazzi, Jusczyk, & Johnson, 2000)? We can ask the same question for infants learning languages other than English: will the IDS preference decline more quickly with age for these infants compared with NAE learning infants? In sum, the MB1 study provides both methodological and theoretical opportunities.

To address all of these questions, after substantial consideration, we elected to use precisely the same speech stimuli across laboratories: samples of IDS from NAE-speaking mothers, the most well-studied IDS source. Our study therefore measures preference for NAE IDS, rather than IDS more generally. This choice was a necessary compromise to meet our other goals. For example, if each laboratory recorded its own stimuli, laboratory-related variability would have been confounded with stimulus variability. Under this design, the burden of time and expertise for participating laboratories would also have been substantially greater. We recognize that this decision furthers the existing NAE bias in the literature (cf. Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010), but as our goal was to replicate an existing phenomenon, we were constrained by the same literature. Our hope is that this initial study will spur additional research using other languages.

At the time of writing, we have divided into committees who are working toward making informed key decisions on all subsequent aspects of this project, including stimuli selection, experimenter training, data collection, and data analyses. We expect to begin data collection in 2017 and complete the study roughly a year later, analyzing and writing up the main results shortly thereafter. We also hope many more manuscripts from this project emerge as participants and the community more generally explore the resulting rich dataset.

CHALLENGES AND BENEFITS OF COLLABORATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Any project has costs—in time, money, and research effort—and for a project as large as ManyBabies, these will be considerable. Nevertheless, we believe that the benefits of the project outweigh these costs, both for individual researchers and for the field as a whole. We discuss challenges for individuals (including early career researchers [ECRs]), laboratories, and the field as a whole in turn and lay out benefits for each in subsequent paragraphs.

Individual researchers

One obstacle to collaborative projects like ManyBabies is that the positive incentives for participation are not as obvious as those for independent research. For example, grant panels and tenure committees may be strongly focused on first- and last-author publications, and may not sufficiently recognize collaborative work even when specific contributions are carefully documented. ECRs in particular are especially vulnerable to the need to produce original scholarship on a relatively short timeline. But given the relatively modest investments of time and effort necessary to make a contribution to a large project, we believe these potential downsides are outweighed by a number of substantial positive benefits.

Improvements in individual scientific practices

Issues of replication and reproducibility are fundamentally not just problems for the community as a whole, but also problems for individual researchers who may both fail to perform replicable research and fail to replicate others’ work. Collaborative projects allow individual researchers to gain experience with community-generated best-practices in experimental design, data analysis, and use of collaborative open-science tools. Such opportunities may be especially valuable for ECRs who do not have access to local training in these practices. As a group, the authors of this paper have found the discussions surrounding project planning to be helpful with their own evolving understanding of issues of reproducibility and study design.

Being a pioneer

Although there are still significant impediments, attitudes toward the value of collaborative and replication work are changing. In the coming years, contributions to collaborative work and projects that work to resolve the replicability crisis may be important factors in hiring, promotion, and funding decisions. Researchers who can show a pattern of early adoption of these new attitudes and approaches will demonstrate a visible and potentially field-shaping commitment to replicability in psychological science.

Opportunities for secondary analysis

Large-scale collaborative projects yield a multitude of data that, in addition to the planned analyses, can be explored for different kinds of research questions, creating additional publication opportunities for the same effort.

Being part of a community

A final important component of the collaborative approach for its participants is the opportunity to collaborate with other researchers. Collaborative efforts provide significant opportunities for networking, mentorship, and the sharing and cross-fertilization of ideas, well beyond those afforded by the standard conference and publication paradigm. With the widespread use of videoconferencing, collaborative projects bring together researchers across timezones in relatively intimate, friendly, supportive, and significant interactions. For ECRs, collaborative projects provide a method for connecting with a broad community of interest and raising awareness about their own skills and abilities. In addition, connections made through collaborative projects may blossom into other professional interactions.

Groups, laboratories, and laboratory heads

Even if individuals may be interested in a collaborative project, the decision to commit the resources of a research group or laboratory may be more complex. For example, often laboratories have funding obligations that require a specific amount of administrative or participant recruitment resources to be devoted to ongoing projects. In the short term, the ManyBabies group has secured modest funding to support laboratory involvement where it would otherwise not be possible, but longer-term financial support may be important for sustaining the group’s efforts. But again, as in the case of individual researchers, there may be a variety of other subsidiary benefits that out weigh the costs of participation.

Standardization of research practices with other laboratories

In group discussions regarding the standardization of practices across laboratories for ManyBabies, many previously unrecognized differences in laboratory practice have emerged (e.g., deciding what counts as “piloting” or when it is acceptable to restart an experimental session). Understanding how different sources of variability impact the robustness and replicability of experimental effects can help laboratories improve their own practices. Furthermore, in the long term, new laboratories could use a ManyBabies protocol to calibrate their laboratory and compare their data against the group standard as a means of establishing reliability.

Implementation of emerging open science practices

The ManyBabies project makes use of a number of emerging practices to ensure reproducibility and to facilitate communication and dissemination, as discussed above. These practices—for example, creating shared project repositories, generating analysis and simulation pipelines, and writing preregistration documents—provide the same kind of benefits to efficiency and reproducibility when used within a single laboratory. Contributors to the Many Babies study will be able to bring these tools back with them to their home laboratory.

The field as a whole

Finally, while it is challenging to coordinate and conduct a multi-site replication study, we believe that there are important reasons why collaborative projects benefit the field as a whole. Replication work leads to more robust science, greater confidence in our findings, and better knowledge-sharing about methodological concerns, which in turn contributes to a culture of data sharing that has benefited fields such as computer science, physics, bioinformatics, and sociology but is not yet widespread in developmental science. We highlight two important positive consequences here.

Funding is tied to community confidence

As any researcher knows, the public controls the purse strings—if a government is voted into office that is less friendly toward research (or even certain kinds of research), this decision will be very quickly felt within the research community by individual researchers who do not get the grant funding they rely on for their work. Setting aside altruistic desires to do high-quality research, our own self-interest in the field of developmental psychology—and infancy research in particular—should drive us to support endeavors like ManyBabies in order to demonstrate to the public our commitment to improving scientific practices.

Creating “best practices” materials and guidelines for experimental procedures and data analysis

The first ManyBabies project will create a push-and-play implementation of a discrimination experiment with a directional prediction. The natural side effect of this study is that it will lead to a set of consensus decisions about experimental procedures using different paradigms for measuring preference, and a set of open-source analysis scripts for the kind of data such experiments generate. These materials will not only lower commitment costs for laboratories involved in the study, but will also create a well-realized template for any future work (by ManyBabies participating laboratories or otherwise) wanting to use these popular developmental methods.

ADVICE FOR SIMILAR MULTISITE REPLICATION EFFORTS

We hope that the ManyBabies project is an initial foray into a new way of doing research in our field. Although our first study is still ongoing, there are already a number of things we have learned that may be beneficial to others embarking on similar endeavors.

First, although the tendency when planning a large, costly project will be to use complex experimental designs or to deal with difficult issues first, we have found that there is much to be done using simple methods to study seemingly well-understood phenomena. Even a straightforward investigation will incur substantial associated complexity as a multisite project, given the variation of methodological practices within developmental research. In MB1, we were conservative in our initial choice of topic: The preference for IDS is a phenomenon that we have strong reason to believe is robust and will lead to a “successful” outcome (in the sense of finding an overall effect in our analysis). Yet making best-practices decisions on method and stimulus was difficult and time-consuming, despite the existence of many similar studies on the topic. Thus, we advise future studies to choose the simplest design that is informative relative to the question of interest.

Second, we suggest that researchers carefully consider policies surrounding authorship, responsibility and credit. From the beginning, ManyBabies decision making has been democratic in nature, and contributors have largely self-selected their contributions (including in the writing of this paper). This collaborative approach has been surprisingly successful, although it has led to some questions around the attribution of authorship. The area of most concern in this regard has been how to encourage and recognize student participation. Specifically, because so many primary investigators were involved in methodological decision making and because the manuscript was largely complete prior to the start of data collection, it has been challenging to involve students in meaningful ways. However, students directly associated with setting up, testing and analyzing the data will appear as authors on the experimental paper that will result from this project. We leave the onus on individual laboratories to find ways to engage involved students meaningfully in the science. Whether this approach is successful remains to be seen. Similar projects in the future might want to start by addressing these authorship issues at the outset of the project.

Third, we strongly recommend that researchers investigate statistical issues prior to beginning recruitment. While we had a priori ideas regarding the overall structure and analysis of the study, collaborative discussions of the developmental sampling scheme and the desire for cross-linguistic comparison led to crucial refinements in the design and analyses to be conducted. In addition, through consultation with statisticians and quantitative researchers, we came to understand early on that our power to draw meaningful inferences about the influence of methodological considerations on out comes would be strongly influenced by the number of participating laboratories. This statistical fact has had important consequences for decisions regarding laboratory recruitment and commitment. We have worked to minimize the burden on any individual laboratory participating in a number of ways, and prioritized including more laboratories at the expense of smaller samples per laboratory (although we do impose a minimum contribution of N = 16 based on the effect size established in the literature discussed above).

Fourth, we suggest that researchers make use of collaboration tools to share the workload and maximize transparency. From the start, ManyBabies has relied heavily on online collaboration, which has made a democratic and accountable decision process possible. Materials are shared, reviewed, and revised either with the whole group or within dedicated task forces that everyone is free to join. Decision-making meetings are documented exhaustively in notes to allow those that could not participate—due to prior commitments or time differences—to catch up and comment. Sharing manuscripts and analysis code through platforms like Google Docs, github, and the Open Science Framework has made it possible to have multiple editors, effectively dividing the workload and speeding up the design and planning process. As MB1 recruits more laboratories to participate, interested researchers can get an overview of the project and join the decision-making process easily by reviewing these shared projects.

Finally, collaborative projects benefit from having at least one individual researcher who can coordinate the project, including initiating decision making, moving discussions forward, setting deadlines, identifying potential publication and funding sources, and acting as spokesperson for disseminating findings at conferences and elsewhere. Having a project coordinator prevents the diffusion of leadership that would otherwise stall progress and completion of the work.

CONCLUSIONS

The foundational purpose of developmental research is to create and disseminate knowledge about processes of change over time that affect both internal representations and external behaviors. This goal is best achieved within a culture of careful, methodological research and widespread sharing of data. The ManyBabies project is a new collaborative effort to promote best practices, evaluate and build on influential findings, and understand different dimensions of variability in laboratory-based infancy research. While data collection is currently ongoing for our first project on IDS preference, other tangible benefits have already emerged from this collaboration.

First, the ManyBabies project served as one inspiration for a recent preconference at the International Congress on Infant Studies, titled Building Best Practices in Infancy Research. This preconference in turn triggered discussions with the Congress leadership, leading to the special issue you are now reading. Such “knock-on” effects are one important benefit of so many people’s efforts being directed at these issues.

Second, participation in the ManyBabies project has already affected how we conduct our own research. For instance, there have been many fruitful discussions during video conferences among members of the ManyBabies 1 project subgroups, including the methods, stimulus, data analysis, and ethics groups. Both macro-level conceptual issues about conducting rigorous research and micro-level methodological issues about a variety of topics have been discussed, such as how to most effectively reduce parent interference during experiments. These discussions have already informed practices within our own laboratories.

Third and finally, the project has served to promote community-building in infancy research outside of the standard framework. This venue for interaction is likely to enhance the rigor and health of our field in the future by promoting reproducibility, improving methods, sharing ideas and data, encouraging reasonable interpretations of data, and building theories. Central to this effort is the idea that science is fundamentally incremental and collaborative. All graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, research staff, and faculty members are welcome to join the ManyBabies project and our community more generally.

Footnotes

Although both the recent Infancy registered reports submission route and efforts for sharing observational data are notable exceptions; cf. Adolph, Gilmore, Freeman, Sanderson, & Millman, 2012; Frank et al., 2016; MacWhinney, 2000; Rose & MacWhinney, 2014; VanDam et al., 2016).

Contributor Information

Michael C. Frank, Stanford University

Elika Bergelson, Duke University.

Christina Bergmann, Laboratoire de Sciences Cognitives et Psycholinguistique (ENS, EHESS, CNRS), Ecole Normale Superieure, PSL Research University.

Alejandrina Cristia, Laboratoire de Sciences Cognitives et Psycholinguistique (ENS, EHESS, CNRS), Ecole Normale Superieure, PSL Research University.

Caroline Floccia, University of Plymouth.

Judit Gervain, CNRS & Université Paris Descartes.

J. Kiley Hamlin, University of British Columbia.

Erin E. Hannon, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Melissa Kline, Harvard University.

Claartje Levelt, Leiden University.

Casey Lew-Williams, Princeton University.

Thierry Nazzi, CNRS & Université Paris Descartes.

Robin Panneton, Virginia Tech.

Hugh Rabagliati, University of Edinburgh.

Melanie Soderstrom, University of Manitoba.

Jessica Sullivan, Skidmore College.

Sandra Waxman, Northwestern University.

Daniel Yurovsky, University of Chicago.

REFERENCES

- Adolph KE, Gilmore RO, Freeman C, Sanderson P, & Millman D (2012). Toward open behavioral science. Psychological Inquiry, 23, 244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CJ, Bahník Š, Barnett-Cowan M, Bosco FA, Chandler J, Chartier CR, … & Della Penna N. (2016). Response to comment on “estimating the reproducibility of psychological science”. Science, 351, 1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benasich AA, & Bejar II (1992). The Fagan test of infant intelligence: A critical review. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 13, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Furrow D, Hill DF, Gable JC, Porter LP, & Jacobs WJ (2014). A duty to describe better the devil you know than the devil you don’t. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 626–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J, Floccia C, Goslin J, & Panneton R (2011). Infants’ discrimination of familiar and unfamiliar accents in speech. Infancy, 16, 392–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ES, & Munafò MR (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14, 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RP, Abraham J, Berman S, & Staska M (1997). The development of infants’ preference for motherese. Infant Behavior and Development, 20, 477–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RP, & Aslin RN (1990). Preference for infant-directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Development, 61, 1584–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristia A, Seidl A, Singh L, & Houston D (2016). Test-retest reliability in infant speech perception tasks. Infancy, 21, 648–667. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst C, Gorman E, & Hamby D (2012). Preference for infant-directed speech in preverbal young children. Center for Early Literacy Learning, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Farran LK, Lee CC, Yoo H, & Oller DK (2016). Cross-cultural register differences in infant-directed speech: An initial study. PLoS One, 11, e0151518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, & Kuhl PK (1987). Acoustic determinants of infant preference for motherese speech. Infant Behavior and Development, 10, 279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Taeschner T, Dunn J, Papousek M, de Boysson-Bardies B, & Fukui I (1989). A cross-language study of prosodic modifications in mothers’ and fathers’ speech to preverbal infants. Journal of Child Language, 16, 477–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floccia C, Keren-Portnoy T, DePaolis R, Duffy H, Delle Luche C, Durrant S,… & Vihman M. (2016). British English infants segment words only with exaggerated infant-directed speech stimuli. Cognition, 148, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MC, Braginsky M, Yurovsky D, & Marchman VA (2016). Wordbank: An open repository for developmental vocabulary data. Journal of Child Language. doi: 10.1017/S0305000916000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, King G, Pettigrew S, & Wilson TD (2016). Comment on “estimating the reproducibility of psychological science”. Science, 351, 1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A, Tamekawa Y, & Kiritani S (2001). Developmental change in auditory preferences for speech stimuli in Japanese infants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44, 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, & Norenzayan A (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2, e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP (2012). Why science is not necessarily self-correcting. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Goldstein MH, Huckeby ER, Owren MJ, & Cooper RP (1995). Dishabituation of visual attention by infant-versus adult-directed speech: Effects of frequency modulation and spectral composition. Infant Behavior and Development, 18, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kemler Nelson DG, Hirsh-Pasek K, Jusczyk PW, & Cassidy KW (1989). How the prosodic cues in motherese might assist language learning. Journal of Child Language, 16, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura C, Thanavishuth C, Burnham D, & Luksaneeyanawin S (2002). Universality and specificity in infant-directed speech: Pitch modifications as a function of infant age and sex in a tonal and non-tonal language. Infant Behavior and Development, 24, 372–392. [Google Scholar]

- Klein RA, Ratliff KA, Vianello M, Adams RB Jr, Bahník Š, Bernstein MJ, … & Cemalcilar Z. (2014). Investigating variation in replicability. Social Psychology, 45, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Andruski JE, Chistovich IA, Chistovich LA, Kozhevnikova EV, Ryskina VL, … & Lacerda F. (1997). Cross-language analysis of phonetic units in language addressed to infants. Science, 277, 684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK (2004). Early language acquisition: Cracking the speech code. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5, 831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn TS (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Golinkoff RM, Houston DM, & Hirsh-Pasek K (2011). Word learning in infant-and adult-directed speech. Language Learning and Development, 7, 185–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B (2000). The CHILDES Project: Tools for analyzing talk, 3rd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Jusczyk PW, & Johnson EK (2000). Language discrimination by English-learning 5-month-olds: Effects of rhythm and familiarity. Journal of Memory and Language, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Newman RS, & Hussain I (2006). Changes in preference for infant-directed speech in low and moderate noise by 4.5- to 13-month-olds. Infancy, 10, 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349, aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg JE, Werker JF, & McLeod PJ (1992). Preference for infant-directed over adult-directed speech: Evidence from 7-week-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 15, 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- Popper K (1963). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rose Y, & MacWhinney B (2014). The PhonBank project: Data and software-assisted methods for the study of phonology and phonological development In Durand J, Gut U, & Kristoffersen G (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corpus phonology (pp. 380–401). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Shute B, & Wheldall K (1995). The incidence of raised average pitch and increased pitch variability in British ‘motherese’ speech and the influence of maternal occupation and discourse form. First Language, 15, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, & Simonsohn U (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22, 1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh L, Nestor S, Parikh C, & Yull A (2009). Influences of Infant-directed speech on early word recognition. Infancy, 14, 654–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaldino PE, & McElreath P (2016). The natural selection of bad science. Royal Society Open Science, 3, 160384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom M (2007). Beyond babytalk: Reevaluating the nature and content of speech input to preverbal infants. Developmental Review, 27, 501–532. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley DJ, & Spence JR (2014). Expectations for replications: Are yours realistic? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen ED, Hill EA, & Saffran JR (2005). Infant-directed speech facilitates word segmentation. Infancy, 7, 53–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDam M, Warlaumont AS, Bergelson E, Cristia A, Soderstrom M, De Palma P, & MacWhinney B (2016). HomeBank, an online repository of daylong child-centered audio recordings. Seminars in Speech and Language, 37, 128–142. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1580745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, & Tees RC (1984). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, & McLeod PJ (1989). Infant preference for both male and female infant-directed talk: A developmental study of attentional and affective responsiveness. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie, 43, 230–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, Pegg JE, & McLeod PJ (1994). A cross-language investigation of infant preference for infant-directed communication. Infant Behavior and Development, 17, 323–333. [Google Scholar]