Abstract

The association between positive and negative affect and sexual behavior in 39 MSM with and without hypersexuality (HS) was explored using ecological momentary assessment. Participants reported their current positive and negative affect three times per day and their sexual behavior each morning and evening. The relationship between affect and sexual behavior differed between men with or without HS. In those with HS, the timing of and interactions between experienced affect differentially predicted types of sexual behavior, indicating differing mechanisms driving partnered sexual behavior and masturbation. These findings lend support to conceptualizing HS behavior as a coping strategy for affective arousal.

Hypersexual behavior is characterized by intense, distressing, and recurrent sexual urges and fantasies that significantly interfere with a person’s daily functioning (e.g., with personal, interpersonal, and occupational responsibilities). Hypersexual behavior is widely disputed with regard to conceptualization, etiology, and nomenclature, and has been dubbed such terms as “sexual addiction” (Carnes, 1983), “compulsive sexual behavior” (Coleman, 1991), “paraphilia related disorder” (Kafka & Prentky, 1997), “hypersexual disorder” (Kafka, 2010), and “out of control sexual behavior” (Braun-Harvey & Vigorito, 2015). Despite such disagreement, one of the hallmarks of all conceptualizations of hypersexuality (Carnes, 1983, 1991; Coleman, 1991, 2003; Kafka, 1997, 2010) is distress resulting from obsessive, compulsive, impulsive, and/or out of control sexual behavior (Black, Kehrberg, Flumerfelt, & Schlosser, 1997; Coleman et al., 2010; Dickenson, Gleason, Coleman, & Miner, 2018). Moreover, several theoretical models of hypersexual behavior indicate that engaging in sexual behavior functions as a strategy to cope with, escape from, or avoid unwanted emotions (Kafka, 2010; Reid & Kafka, 2014). Yet, to date, our understanding of how day-to-day changes in negative and positive affect are related to day-to-day changes in sexual behavior among men who exhibit hypersexual behavior remains limited.

Negative affect (e.g., sadness, fear) and mood (e.g., depressed, anxious) typically impede sexual interest and arousal (Bancroft et al., 2003a, 2003b), although some men have shown increases in sexual interest and arousal after experiencing negative affect. Moreover, the link between negative affect and sexual behavior appears to vary across individuals. For example, men who have sex with men (MSM) show increased sexual risk behavior following anxious affective states, but only if they have low trait anxiety (Mustanski, 2007). Thus, negative affect can either augment or impede sexual interest, arousal, and behavior depending on additional traits of the individual. Perhaps the degree to which negative affect motivates sexual behavior is also different for men who vary in their tendency to exhibit hypersexual behavior.

Research has consistently demonstrated that men with hypersexual behavior exhibit emotion regulation difficulties. Many men with hypersexual behavior exhibit high negative emotionality (Miner et al., 2016); negative emotional states related to their sexual behavior, such as shame, guilt, and hostility toward themselves (Reid, 2010); are more vulnerable to general life stressors (Laier & Brand, 2017); and have greater deficits in their ability to regulate emotions (Leppink, Chamberlain, Redden, & Grant, 2016; Rizor, Callands, Desrosiers, & Kershaw, 2017). Various theoretical models indicate that hypersexual behavior serves to reduce unwanted emotions (Bancroft & Vukadinovic, 2004; Coleman, 1991). Such behavior initially provides relief, but this relief is temporary and ultimately leads to guilt and shame about engaging in problematic sexual behavior, thus, re-entering the cycle.

Yet, the notion that the cycle of hypersexual behavior begins with negative emotionality has proven inconsistent. On one hand, research examining reports of reasons for engaging in sexual behavior has corroborated the hypothesized link between negative emotionality and sexual behavior. Some research has indicated that sexual behavior may be related to difficulties with negative affect regulation among hypersexual men, and hypersexual men self-report that negative affect motivates sexual behavior (Parsons et al., 2008). Individuals who compulsively view pornography exhibited higher general stress levels, reported viewing sexual imagery for the purposes of sensation seeking or emotional avoidance, and showed an increase in positive affect immediately after viewing sexual imagery (Laier & Brand, 2017). Moreover, hypersexual MSM have reported that they engage in sexual behavior to cope with negative affect and gain a sense of affirmation and validation that they could not obtain from non-sexual social relationships, whereas MSM without hypersexual behavior did not (Parsons et al., 2008).

Other research has not substantiated the link between negative affect and sexual activity. Grov, Golub, Mustanski, and Parsons (2010) found that among MSM, daily negative affect was associated with decreased likelihood of partnered sexual activity that same day. Contrary to expectations and the abovementioned studies, men with and without HS with and without hypersexual behavior did not differ in the degree to which negative affect was associated with partnered sexual activity. Such inconsistent findings indicate that the role of affective regulation in predicting sexual behavior is not clear and may involve the interaction of positive and negative affective changes.

Such contradictory results may be explained by differences in methodology. Studies varied in their assessment of state versus trait levels of affect, the valence of the affective state (positive versus negative), assessment of temporal versus concurrent effects (i.e., does affect lead to sexual behavior?), and assessment of whether the relationship between affective states (or traits) and sexual behavior differ between men with and without HS. To date, no study has examined whether the ways in which negative or positive affect leads to a greater or lower likelihood of engaging in sexual behavior differs among men with and without HS.

The current study aims to address this gap by examining the day-to-day relation between positive and negative affect and various types of sexual behavior (viewing sexual imagery, engaging in masturbation sexual activity, and engaging in partnered sexual activity) using a sample of MSM with and without hypersexuality. By using Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA: Dunton, Liao, Intille, Spruijt-Metz, & Pentz, 2011; Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008), we examined temporal ordering of affect and sexual behavior. This study expands existing research by focusing on positive affect, as well as negative affect, and by assessing masturbation and partnered sexual activity. Given prior research and proposed theoretical conceptualizations that hypersexual behavior serves as a coping strategy, we expected that negative affect will be associated with greater likelihood of engaging in all three types of sexual behavior among hypersexual men. Further, we expected that positive affect, but not negative affect, will be associated with greater likelihood of engaging in all three types of sexual behavior among MSM without hypersexuality.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 39 men who have sex with men who were recruited as part of a larger study of the psychological and cognitive mechanisms underlying hypersexuality (for more details see Miner et al., 2016). In brief, participants were recruited from a metropolitan area in the Upper Midwest. Participants were eligible if they were 18 years old or older, had engaged in sex with at least one man in their lifetime, and had engaged in sexual behavior within the last 90 days. Potential participants were excluded if they showed indications of a major thought disorder or physical disability that interfered with erectile function. Demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

HS |

|||||||

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | t | df | |

| Age | 29.08 | 7.92 | 26 | 38.83 | 10.74 | 12 | 3.15* | 36 |

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %, χ2) | 26 | 13 | 6.29 | 3 | ||||

| Caucasian | 23 | 88.5% | 8 | 61.5% | ||||

| African American | 2 | 5.5% | 1 | 7.7% | ||||

| Hispanic | 0 | 0% | 1 | 7.7% | ||||

| Other | 1 | 3.8% | 3 | 23.1% | ||||

| Number of Days Participants Masturbated | 4.12 | 3.64 | 25 | 5.23 | 4.21 | 13 | .85 | 36 |

| Average Number of Times Masturbated Within a Day | 0.60 | 0.81 | 25 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 13 | −.01 | 36 |

| Average Time Spent Watching Porn within a Day | 0.38 | 0.29 | 25 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 13 | .50 | 36 |

| Average Time Spent Searching for Sexual Partners within a Day | 0.35 | 0.38 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 13 | .29 | 36 |

| Number of Days Participants had Sex | 1.40 | 1.32 | 25 | 1.08 | 1.61 | 13 | −.66 | 36 |

| Average Number of Sex Partners during one Sexual Encounter | 0.15 | 0.21 | 25 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 13 | .37 | 36 |

| Number of Days Participants Had Unprotected Penetrative Sex | 0.71 | 1.05 | 17 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 7 | .35 | 22 |

| Number of Days Participants Engaged in Drug Use During Sex | 0.24 | 0.44 | 17 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 7 | −.10 | 22 |

| Average Morning Negative Affect | 5.99 | 1.14 | 25 | 7.00 | 2.02 | 13 | 1.96† | 36 |

| Average Daytime Negative Affect | 5.92 | 0.97 | 26 | 7.27 | 1.91 | 13 | 2.95* | 37 |

| Average Morning Positive Affect | 10.34 | 2.75 | 25 | 13.71 | 4.99 | 13 | 2.70* | 36 |

| Average Daytime Positive Affect | 12.11 | 3.30 | 26 | 16.07 | 4.09 | 13 | 3.26* | 37 |

| Has a Main Partner (n, %, χ2) | n=9 | 34.6% | 26 | n=5 | 38.5% | 13 | .06 | 1 |

p < .05

p < .06.

Procedure

Participants came into the laboratory to complete an initial questionnaire, a diagnostic interview to assess for hypersexuality (HS), and receive instructions for the “at home” portion of the study. For 15 days participants completed daily diaries assessing their negative and positive affect and sexual behavior every morning (8am) and night (8pm). Participants also received random “pings” to complete questions about their emotional affect, one between 8 am and noon (hereto referred as morning affect) and the other between noon and 8pm (hereto referred as midday affect). Participants were required to complete the diary within a two-hour window. Diary entries were made online, each entry was time- and date-stamped, and data was maintained through a secure server at the primary investigator’s institution.

Measures

Participant characteristics.

Participants underwent an interview based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) which was adapted to examine criteria for HS. Responses were coded by two trained research assistants. In cases of uncertainty or conflict between the ratings of the research assistants, two senior clinicians involved in the study reviewed the cases carefully to ascertain group membership. Hypersexuality criteria were operationalized as follows: (A) over a period of at least 6 months, experiencing recurrent intense sexual arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving one or more of the following: compulsive cruising and multiple partners; compulsive masturbation, including use of internet pornography and cybersex; and/or compulsive sex within a relationship; (B) the fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning; and (C) not due to another medical condition, such as substance abuse, or attributable to another psychiatric disorder such as mania, or a normal developmental stage (see Miner et al., 2016 for a complete description of this procedure). Because having a partner has the potential to affect frequency of sexual behavior, participants were asked whether they had a primary partner lasting at least 3 months in the past 90 days.

Emotional affect.

Emotional affect was assessed four times a day using the International Positive and Affect Schedule Short Form (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, 2007). The I-PANAS-SF assesses independent (uncorrelated) dimensions of positive and negative affect that has unambiguous meaning across cultures and has shown good internal consistency, convergent validity, cross-cultural invariance, and discriminant validity (Thompson, 2007). Positive affect reflects one’s level of positive engagement and negative affect reflects aversive mood states. Higher scores on both positive and negative affect reflect the experience of emotional affect whereas the lower scores on positive and negative affect reflect the absence of emotional involvement (e.g., low negative affect is characterized by being calm and relaxed, rather than happy per se).

Participants rated their current intensity of 10 emotions four times a day on a 5-point scale, 1, not at all to 5, extremely. Positive affect included ratings of active, determined, attentive, inspired, and alert (Cronbach’s alpha for this index was .87). Negative affect included ratings of afraid, upset, hostile, ashamed, and nervous (Cronbach’s alpha for this index was .76). Responses to each item were summed to obtain a total score for positive affect and for negative affect, such that each scale score ranged from 5–25.

Sexual behavior.

Participants reported the time spent viewing sexual imagery, choosing from 4 responses: did not view any porn, less than 2 hours, 2–4 hours, more than 4 hours. This variable was collapsed into two categories (not viewing sexual imagery, viewing sexual imagery) as the latter categories (more than 4 hours and 2–4 hours) did not have sufficient observations for analysis. Participants also reported whether they engaged in masturbation sexual activity and partnered sexual activity. Participants reported on their sexual behavior during each time period (between 8am and 8pm and between 8pm and 8am). Thus, the morning diary inquires about whether they masturbated, engaged in partnered sexual activity (which included oral or penetrative sex), and the amount of time spent viewing sexual imagery during the previous night (between 8pm and 8am), whereas the daytime diary represents daytime sexual behavior (between the hours of 8am and 8pm).

Analytic Strategy

To assess whether individuals with and without HS showed differences in the degree to which positive and negative affect predicted sexual behavior (likelihood of viewing pornography, engaging in masturbation, and engaging in partnered sexual activity), we examined how daytime affect (constituting affect ratings from the two momentary assessments and the evening daily diary) was associated with nighttime sexual behavior (reported in the morning). To maintain orthogonality between affect and sexual behavior, affect upon awakening was excluded from analyses. Analyses were conducted with multilevel random coefficient modeling (MRCM, employed with WHLM; Bryk & Raudenbusch, 1992) to represent the nested nature of the data, in which lower level units (sexual behavior and emotional affect) vary within persons and second level units vary between persons (e.g., hypersexuality diagnosis). Models were estimated using binomial distributions for masturbation and partnered sexual activity and viewing sexual imagery using La Place estimation procedures. The following Level 1 model predicts each participant’s nighttime sexual behavior from his previous daytime’s positive and negative affect, controlling for their sexual behavior during the daytime across the 15 day period:

This model was analogous to calculating a separate regression model for each man, in which the ‘‘sample’’ comprised his 15 days of data. Positive and negative affect were ipsatized, or “group centered” around each man’s 15-day mean. Each coefficient was interpreted as the untransformed logistic regression coefficients associated with a linear rate of change in the logit (i.e., the natural log of the odds ratio). The intercept, π 0 , represented the odds of masturbating versus not masturbating for a man who did not masturbate between 8am and 8pm on the first day of the study when morning, midday, and evening NA and PA were at his typical, or average, level. The coefficients of interest were π 3, π 4, and π 5.

To obtain the most parsimonious model, the level 1 intercept (e.g., average nighttime masturbation) was allowed to vary randomly across persons, but random effects were excluded from other slopes. Level 2 coefficients of the intercepts represent the strength and direction between day-to-day changes in emotional affect (PA, NA, interaction between NA and PA) and day-to-day changes in the likelihood of engaging in masturbation (or other sexual behavior) over time. All non-significant interactions were dropped from the final models. To assess how relations between affect and sexual behavior varied between MSM with and without HS, we entered group as a level 2 moderator, dummy coded such that “0” represented individuals with CSB. To delineate the significant interactions between positive and negative affect and to delineate the significant differences between individuals with and without HS, we conducted simple slopes, at one standard deviation above and below the sample mean level of NA among individuals with HS. This procedure was repeated for individuals without HS by recoding group such that “0” represented individuals without HS. To ease interpretation, effects are depicted graphically as predicted probabilities (Yang & Land, 2013)

Results

Differences in Overall Affect and Sexual Behavior

We first examined whether MSM with and without HS differed in their sociodemographics, amount of sexual behavior across the 15-day period (number of days participants engaged in masturbation and partnered sexual activity, average time spent viewing sexual imagery per day), and average levels of morning positive and negative affect across the 15-day period. As shown in Table 1, individuals with HS were significantly older, and were more likely to have higher positive and higher negative affect across the 15-day period, but showed no differences in partnered sexual activity or masturbation sexual activity.

Does Affect Predict Partnered Sexual Activity Differently for Individuals with and without HS?

Table 2 displays the degree to which positive affect and negative affect are associated with subsequent sexual behavior (partnered sexual behavior, masturbation, viewing sexual imagery), controlling for sexual behavior that occurred earlier in the day. The data evidences that these associations vary among individuals with and without HS. With regard to partnered sexual behavior, we found that relation between prior and subsequent partnered sexual activity differed among individuals with and without HS. Simple slopes revealed that among individuals without HS, partnered sexual behavior earlier in the day was unrelated to partnered sexual behavior that subsequent night (b=.42, SE=.70, p=NS). In contrast, when individuals with HS engaged in partnered sexual behavior earlier in the day, they were more likely to engage in partnered sexual activity that subsequent night (b=3.85, SE=1.03, OR=46.8;CI: 6.2–356.3).

Table 2.

Logistic Multilevel models assessing nighttime sexual behavior predicted by the preceding daytime’s mood and behavior moderated by HS diagnosis.

| Dependent Variable: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Masturbation | Porn | ||||

| Coefficient (SE) |

OR (CI) | Coefficient (SE) |

OR (CI) | Coefficient (SE) |

OR (CI) | |

| Intercept | −4.17 (1.1) | 0.02 (0,0.15)* | 0.49 (0.55) | 1.63 (0.53,5.01) | −0.49 (0.47) | 0.61 (0.24,1.57) |

| Group | 1.91 (1.15) | 6.75 (0.65,70.07) | −0.85 (0.61) | 0.43 (0.12,1.49) | −0.14 (0.53) | 0.87 (0.29,2.56) |

| Prior behavior | 3.85 (1.03) | 46.84 (6.16,356)* | −1.67 (0.59) | 0.19 (0.06,0.61)* | −0.33 (0.67) | 0.72 (0.19,2.69) |

| Group | −3.42 (1.25) | 0.03 (0,0.38)* | 1.14 (0.65) | 3.12 (0.86,11.37) | 0.36 (0.74) | 1.43 (0.33,6.19) |

| Morning Affect | ||||||

| NA | 0.98 (0.18) | 2.67 (1.87,3.82)* | 0 (0.15) | 1 (0.75,1.34) | 0.04 (0.12) | 1.04 (0.83,1.31) |

| Group | −0.93 (0.28) | 0.40 (0.23,0.69)* | 0.08 (0.17) | 1.08 (0.78,1.51) | 0.08 (0.14) | 1.09 (0.82,1.43) |

| PA | 0.49 (0.18) | 1.63 (1.14,2.33)* | −0.03 (0.11) | 0.97 (0.77,1.21) | −0.08 (0.08) | 0.93 (0.79,1.09) |

| Group | −0.47 (0.2) | 0.62 (0.42,0.92)* | 0.01 (0.12) | 1.01 (0.79,1.29) | 0.09 (0.10) | 1.09 (0.9,1.32) |

| NA × PA | −0.26 (0.12) | 0.77 (0.61,0.97)* | – | – | – | – |

| Group | 0.35 (0.14) | 1.42 (1.08,1.86)* | – | – | – | – |

| Midday Affect | ||||||

| NA | 0.37 (0.14) | 1.44 (1.09,1.92)* | 0.07 (0.11) | 1.08 (0.87,1.34) | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.94 (0.83,1.06) |

| Group | −0.19 (0.21) | 0.83 (0.55,1.26) | −0.17 (0.14) | 0.85 (0.65,1.11) | 0.07 (0.13) | 1.07 (0.83,1.38) |

| PA | −0.29 (0.17) | 0.75 (0.53,1.05) | −0.12 (0.07) | 0.88 (0.77,1.02) | −0.05 (0.07) | 0.95 (0.83,1.08) |

| Group | 0.41 (0.2) | 1.51 (1.02,2.23)* | 0.25 (0.1) | 1.28 (1.05,1.55)* | 0.08 (0.09) | 1.08 (0.91,1.28) |

| NA × PA | – | – | 0.01 (0.03) | 1.01 (0.96,1.06) | – | – |

| Group | – | – | 0.11 (0.05) | 1.12 (1,1.24)* | – | – |

| Evening Affect | ||||||

| NA | 0.26 (0.31) | 1.29 (0.71,2.37) | 0.04 (0.23) | 1.04 (0.65,1.64) | −0.24 (0.23) | 0.79 (0.5,1.23) |

| Group | −0.15 (0.49) | 0.86 (0.33,2.29) | −0.29 (0.26) | 0.75 (0.45,1.25) | −0.29 (0.37) | 0.75 (0.36,1.54) |

| PA | −0.19 (0.11) | 0.83 (0.67,1.02) | 0.11 (0.09) | 1.12 (0.93,1.35) | 0.08 (0.07) | 1.08 (0.94,1.25) |

| Group | 0.2 (0.18) | 1.22 (0.85,1.73) | −0.12 (0.11) | 0.89 (0.72,1.1) | −0.07 (0.10) | 0.93 (0.77,1.13) |

| NA × PA | – | – | 0.33 (0.06) | 1.39 (1.23,1.57)* | 0.21 (0.09) | 1.23 (1.03,1.48)* |

| Group | – | – | −0.38 (0.08) | 0.69 (0.59,0.8)* | −0.24 (0.10) | 0.79 (0.64,0.97)* |

p < .05.

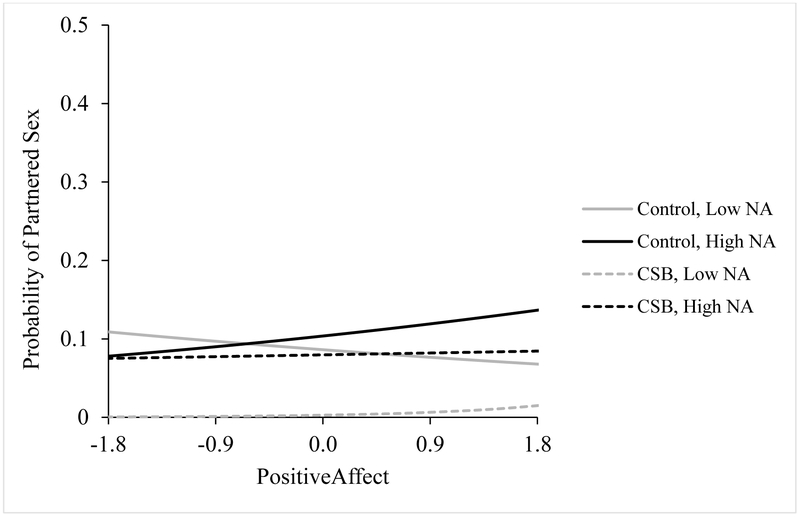

We also found that degree to which negative and positive affect were associated with nighttime partnered sexual activity differed among individuals with HS and individuals without HS (see Table 2; Figure 1). For individuals without HS, morning, midday, and evening affect did not predict partnered sexual activity (p’s=NS). Among individuals with HS (see Table 2), we found that on average (i.e., main effect), day-to-day increases in morning NA, morning PA, and midday NA (relative to their own average level of affect) were associated with greater likelihood of subsequently engaging in partnered sexual activity. We found a significant interaction between morning NA and PA in predicting nighttime sexual activity. Among individuals with HS, day-to-day increases in morning PA, relative to their own average level of morning PA, were associated with greater likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual activity, on days that their NA was average (see Table 2) or low (b=.94, SE=.37, p=.012; see Figure 1). In contrast, on days that that their morning NA was high, day-to-day changes in morning PA had no effect on the likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual activity (p>.5).

Figure 1.

Effect of morning positive and negative affect on likelihood of partnered sexual activity among MSM without and with HS.

Does Affect Predict Masturbation Differently for Individuals with and without HS?

With regard to masturbation, we found midday and evening NA and PA predicted subsequent masturbation differently among individuals with and without HS (see Table 2; Figure 2). Among individuals without HS, the interaction between midday (b=.12, SE=.12, OR=1.12 (95% CI: 1.02–1.24), p=.02), but not evening (p=NS), positive and negative affect significantly predicted the likelihood of engaging in masturbation. Among individuals without HS, day-to-day increases in midday PA, relative to their own average level of midday PA, were associated with greater likelihood of engaging in masturbation, but only on days that their midday NA was high (b=.32, SE=.12, χ2=7.62, p=.005).

Figure 2.

Effect of midday and evening positive and negative affect on likelihood of masturbating among MSM without and with HS.

Among individuals with HS, the interaction between evening, but not midday (see Table 2), positive affect and negative affect predicted likelihood of engaging in masturbation. Among individuals with HS, day-to-day increases in evening PA, relative to their own average level of evening PA, were associated with greater likelihood of engaging in masturbation, but only on days that their evening NA was high (b=.60, SE=.31, χ2=3.76, p=.049). There was also a trend, such that individuals with HS experienced low evening NA, day-to-day increases in PA tended to lead to decreased likelihood of engaging in masturbation (b=−.37, SE=.21, χ2=2.97, p=.081).

Does Affect Predict Viewing Sexual Imagery Differently for Individuals with and without HS?

We found that the interaction between evening positive and negative affect predicted viewing sexual imagery and this association differed among individuals with and without HS (see Table 2; Figure 3). The interaction between evening positive and negative affect predicted nighttime viewing of sexual imagery among individuals with HS, but not among individuals without HS (p>.2). Among individuals without HS, morning, midday, and evening affect did not significantly predict likelihood of viewing sexual imagery (p’s>.06).

Figure 3.

Effect of positive and negative affect on watching pornography among MSM without and with HS.

Among individuals with HS, when NA was at typical levels (mean average), day-to-day changes in evening PA did not affect the likelihood of viewing sexual imagery (see Table 2). In contrast, day to day increases in evening PA, relative to their own average level of evening PA, was associated with greater likelihood of viewing sexual imagery on days when their NA was high (b=.39, SE=.20, χ2=3.9, p=.05). Moreover, day to day decreases in evening PA, relative to their own average level of evening PA, was associated with greater likelihood of viewing sexual imagery on days when their NA was low (b=−.23, SE=.10, χ2=5.8, p=.01).

In summary, individuals without HS were generally not any more likely to engage in partnered sexual activity, masturbate, or view sexual imagery based on their emotional state. The exception was that, when individuals without HS experienced high levels of midday NA, increases in midday PA led to greater likelihood of masturbating. In contrast, individuals with HS were more prone to engaging in sexual activity depending on their emotional state. Among individuals with HS, increases in morning NA and PA and midday NA led to greater likelihood of engaging in partnered sex. As well, when evening NA was low, increases in evening PA, relative to their own average level, led to greater likelihood of engaging in sexual activity. With regard to masturbation, when evening NA was high, increases in evening PA, relative to their own average level, led to greater likelihood of masturbating. That is, individuals with HS were more likely to engage in masturbation on days when both NA and PA were high. Finally, when individuals with HS experienced low levels of NA, decreases in evening PA led to higher likelihood of viewing sexual imagery. When they experienced high levels of NA, increases in PA led to higher likelihood of viewing sexual imagery. In other words, individuals with HS were more likely to view sexual imagery when both their PA and NA was high or when both their NA and PA were low.

Discussion

This study was designed to assess the association between positive and negative affect and sexual behavior in men who met criteria for HS and those who did not. Our data indicates that affect has differential associations with sexual behavior for men with HS and those without. Positive and negative affect was associated with masturbation for those without HS. Yet, for men with HS, changes in positive and negative affect were related to likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual behavior, masturbation, and viewing sexually explicit material. However, changes in positive and negative affect predicted the likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual behavior, masturbation, and viewing sexually explicit material in different ways. Finally, the timing of affect mattered, with different relationships between partnered sexual behavior or solitary sexual behavior and morning, mid-day, and evening affect.

Among men who met criteria for HS, increases in morning NA and PA and increases in midday NA prompted higher likelihood of engaging in sexual behavior. Yet, increases in individual’s morning PA prompted greater likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual behavior only when morning NA was low or at average levels. Incentive motivation may explain this interaction effect. According to incentive motivation, when negative emotion is present, individuals feel less motivated to take action. Therefore, the presence of some level of engagement, or motivation to take action would be necessary for any coping strategy to be implemented. Our measure of affect (PANAS) was designed to measure positive and negative affect as independent dimensions (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) such that positive affect is less about happiness and more about being engaged, that is alert, determined, and active (Watson et al., 1988). Thus, the abovementioned interaction seems to indicate that engaging in partnered sexual behavior was related to increases in feeling engaged and alert in the morning, combined with a low to typical level of morning negative affect. Our results extend previous research documenting that men with HS show greater reactivity to negative affect (Miner et al., 2016; Reid, Stein, & Carpenter, 2011; Walton, Cantor, & Lykins, 2017). Additionally, our findings demonstrated that sexual behavior earlier in the day, increases in morning NA, and increases in midday NA were also associated with greater likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual behavior that evening. One plausible explanation is that after engaging in the earlier sexual behavior, perhaps men with HS did not achieve sexual satisfaction, or they may have experienced negative affect in response to their sexual behavior (Carnes, 1983; Coleman, 1991). Theories have suggested that individuals with HS expect pleasure and abatement of the negative affect from engaging in sexual behavior, despite the actual experience of worsening negative affect following the previous sexual behavior (Redish, 2004). Although our study cannot determine whether daytime sexual behavior preceded the negative affect, our study does suggest that negative affect may be lead to further engagement of partnered sexual behavior.

One important implication of our findings is its potential to explain the differences in findings between those studies that focus on internet pornography use and those studies that define HS by frequency of partners or total sexual outlet (Kafka, 2000). Our study shows that negative and positive affect interact differently to predict partnered sexual behavior in MSM with HS and those without HS than to predict masturbation or viewing sexually explicit material, which show comparable relations with negative and positive affect. Thus, it is likely that the mechanisms driving HS characterized by partnered sexual behavior may be different from that driving HS as defined by masturbation and pornography use. Importantly, we found the combination of high positive affective activation and high negative affective activation increased the probability of engaging in masturbation and viewing sexual imagery among individuals with HS. This appears consistent with some of the neuroimaging studies which find increased activity in dopaminergic structures in the central nervous system (Brand, Snagowski, Laier, & Maderwald, 2016) when studying individuals whose HS is characterized by high levels of problematic use of internet sexual imagery. Furthermore, this is in line with previous research suggesting that when high positive and high negative affect occurred together, often termed ambivalent affect, high levels of sexual arousal, both subjective and measured erectile response, and high levels of reported sexual desire were induced by exposure to sexual stimuli (Peterson & Janssen, 2007).

Finally, our findings demonstrate that not only does the likelihood of engaging in various forms of sexual behavior vary not only according to the type of affect (either positive, negative, or a combination), but to the timing of such affective experiences. The likelihood of engaging in partnered sexual behavior changed depending on affective arousal experienced in the morning or earlier in the day whereas the likelihood of engaging in masturbation and viewing sexual imagery changed depending on the more proximal affective experience (i.e., during the evening just prior to when the sexual activity occurred). The fact that partnered sexual activity and masturbation or viewing sexual imagery were affected by distinct emotions at different times of the day suggest that engaging in partnered sex may serve a different purpose than masturbation and viewing of sexual imagery for HS individuals. The immediate access to sexual imagery on the internet may increase the potency of such activities as a coping strategy for negative affect, whereas partnered sexual behavior may be driven by the need for affiliation or affirmation, thus by previously experienced negative affect such as loneliness. Further, engaging in partnered sexual behavior requires more planning and intention than masturbation and viewing sexual imagery. This could also could account for associations between emotions experienced either previously in the day or proximal to the behavior. These possibilities present important avenues for future research.

This study has a number of limitations. Both the emotional states and the sexual behavior were assessed by self-report. Additionally, the EMA requires that individuals respond after being prompted or at the standardized response times. There may be response bias where participants fail to respond when in certain emotional states or when engaging in or failing to engage in the behavior of interest. Additionally, the sample size for this study is rather small. However, given the number of responses per subject, statistical power is not compromised by the sample size. Finally, this study focuses exclusively on men who have sex with men, without concomitantly assessing the sociocultural context (e.g., minority stress). Thus, the degree to which our findings are related to syndemic stress remains unknown. This represents a critical avenue for future research.

At this point, it is still unclear whether HS is an addictive, impulsive, compulsive, or high drive related process. The fact that sexual behavior at one time point predicted later sexual behavior may indicate that HS individuals have higher sex drive, thus one sexual experience does not satisfy their need for sexual gratification. However, it could also be that individuals with HS have difficulties regulating emotions and behavioral control, in which their desire to reduce unwanted emotions increases the likelihood of pursuing sexual activity. Importantly, our data do not corroborate models of sexual addiction. Rather, our findings suggest that emotional avoidance may be key to the experience of individuals who struggle with HS. Future research should further explore emotion regulation difficulties in its relevant sociocultural context.

Additionally, our findings indicate that different affective mechanisms drive partnered sexual activity and masturbation in individuals with HS. These mechanisms can be further explicated in future research, which should use larger, more diverse samples. Importantly, these data indicate that the mechanisms that drive HS may vary within person and across people. Researchers have indicated that HS is driven by multiple mechanisms and thus some differences between groups can be washed out (Coleman, 2011; Coleman et al., 2018). However, our findings do indicate that across individuals who meet criteria for HS, sexual behavior serves to regulate negative affect and is driven by affective arousal. Further research might look at different types of people with hypersexuality (those that are driven by various factors such as affect dysregulation, anxiety reduction, impulse control, sensation seeking), sub-classifying these individuals, and testing these hypotheses regarding effect of emotions on sexual behavior. Now that the International Classification of Diseases, Version 11 has recognized a discrete category of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder under the parent category of impulse control disorders (WHO, 2018), it is incumbent upon us to better search for an understanding of underlying mechanisms which might lead to more individualized treatment approaches while also being careful to not pathologize normative sexual behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to Michael Miner (R01MH094229). The authors would like to thank Cathy Strobel-Ayres, the project coordinator, without whom this project would never have been completed. We would also like to thank Ann Person, our research assistant who conducted much of the data collection, and Ross Crosby, PhD, who provided the methodology and daily management of the daily diary/ecological momentary assessment procedure. We would also like to thank the project co-investigators, Nancy Raymond, Erick Janssen, and Angus MacDonald, III. Finally, we want to thank Heidi Fall for contributing her expertise in editing, formatting, and references for the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michael H. Miner, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School.

Janna Dickenson, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School..

Eli Coleman, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School..

References

- Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, & Long JS (2003a). The relation between mood and sexuality in heterosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(3), 217–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1023409516739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, & Long JS (2003b). Sexual risk-taking in gay men: The relevance of sexual arousability, mood, and sensation seeking. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(6), 555–572. doi: 10.1023/A:1026041628364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J, & Vukadinovic Z (2004). Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. The Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 225–234. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Kehrberg LL, Flumerfelt DL, & Schlosser SS (1997). Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(2), 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M, Snagowski J, Laier C, & Maderwald S (2016). Ventral striatum activity when watching preferred pornographic pictures is correlated with symptoms of Internet pornography addiction. Neuroimage, 129, 224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Harvey D, & Vigorito MA (2015). Treating out of control sexual behavior: Rethinking sex addiction. New York, Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, & Raudenbusch SW (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data management methods. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P (1983). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. Minneapolis, MN: CompCare. [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P Don’t call it love: Recovery from sexual addiction. New York: Bantam Books; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E (1991). Compulsive sexual behavior: New concepts and treatments. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 4(2), 37–52. doi: 10.1300/J056v04n02_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E (2003). Compulsive sexual behavior: What to call it, how to treat it? SIECUS Report, 31(5), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E (2011) Impulsive/compulsive sexual behavior: Assessment and treatment In Grant JE, & Potenza MN (Eds.), The oxford handbook of impulse control disorders (pp. 375–388). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Dickenson JA, Girard A, Rider GN, Candelario-Pérez LE, Becker-Warner R, Kovic AG, & Munns R (2018). An integrative biopsychosocial and sex positive model of understanding and treatment of impulsive/compulsive sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2018.1515050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Horvath KJ, Miner M, Ross MW, Oakes M, & Rosser BRS (2010). Compulsive sexual behavior and risk for unsafe sex among internet using men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(5), 1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9507-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson JA, Gleason N, Coleman E, & Miner Michael H. (2018). Prevalence of distress associated with difficulty controlling sexual urges, feelings, and behaviors in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184468–e184468. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Liao Y, Intille SS, Spruijt-Metz D, & Pentz M (2011). Investigating children’s physical activity and sedentary behavior using ecological momentary assessment with mobile phones. Obesity, 19(6), 1205–1212. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Mustanski B, & Parsons JT (2010). Sexual compulsivity, state affect, and sexual risk behavior in a daily diary study of gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0020527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafka MP (1997). Hypersexual desire in males: An operational definition and clinical implications for males with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(5), 505–526. doi: 10.1023/A:1024507922470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafka MP (2000). Paraphilia-related disorders: The evaluation and treament of nonparaphilic hypersexuality In Leiblum SR, & Rosen RC (Eds). Principles and practice of sex therapy (3rd ed., pp. 471–503. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka MP (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafka MP, & Prentky RA (1997). Compulsive sexual behavior characteristics. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11), 1632–1632. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laier C, & Brand M (2017). Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 5, 9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppink EW, Chamberlain SR, Redden SA, & Grant JE (2016). Problematic sexual behavior in young adults: Associations across clinical, behavioral, and neurocognitive variables. Psychiatry Research, 246, 230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner MH, Swinburne Romine R, Raymond N, Janssen E, MacDonald A, & Coleman E (2016). Understanding the personality and behavioral mechanisms defining hypersexuality in men who have sex with men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(9), 1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B (2007). The influence of state and trait affect on HIV risk behaviors: A daily diary study of MSM. Health Psychology, 26(5), 618–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, DiMaria L, Wainberg ML, & Morgenstern J (2008). Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(5), 817–826. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, & Janssen E (2007). Ambivalent affect and sexual response: The impact of co-occurring positive and negative emotions on subjective and physiological sexual responses to erotic stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(6), 793–807. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9145-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD (2004). Addiction as a computational process gone awry. Science, 306(5703), 1944–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.1102384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RC (2010). Differentiating emotions in a sample of men in treatment for hypersexual behavior. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 10(2), 197–213. doi: 10.1080/15332561003769369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RC, & Kafka MP (2014). Controversies about hypersexual disorder and the DSM-5. Current Sexual Health Reports, 6(4), 259–264. doi: 10.1007/s11930-014-0031-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RC, Stein JA, & Carpenter BN (2011). Understanding the roles of shame and neuroticism in a patient sample of hypersexual men. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(4), 263–267. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182125b96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizor A, Callands T, Desrosiers A, & Kershaw T (2017). (S)He’s gotta have it: Emotion regulation, emotional expression, and sexual risk behavior in emerging adult couples. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 24(3), 203–216. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2017.1343700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ER (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. doi: 10.1177/0022022106297301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MT, Cantor JM, & Lykins AD (2017). An online assessment of personality, psychological, and sexuality variables associated with self-reported hypersexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 721–733. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0606-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1630268048

- Yang YC, & Land KC (2013). Misunderstandings, mischaracterizations, and the problematic choice of a specific instance in which the IE should never be applied. Demography, 50(6), 1969–1971. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0254-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]