Ceftolozane-tazobactam is considered to be a last-resort treatment for infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although resistance to this antimicrobial has been described in vitro, the development of resistance in vivo has rarely been reported. Here, we describe the evolution of resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam of P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from the same patient during recurrent infections over 2.5 years.

Keywords: AmpC, G183D, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam

ABSTRACT

Ceftolozane-tazobactam is considered to be a last-resort treatment for infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although resistance to this antimicrobial has been described in vitro, the development of resistance in vivo has rarely been reported. Here, we describe the evolution of resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam of P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from the same patient during recurrent infections over 2.5 years. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results showed that 24 of the 27 P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from blood (n = 18), wound (n = 2), pulmonary (n = 1), bile (n = 2), and stool (n = 4) samples from the same patient were susceptible to ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam but resistant to ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem, and meropenem. Three clinical isolates acquired resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam along with a partial restoration of piperacillin-tazobactam and carbapenem susceptibilities. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals that all isolates were clonally related (sequence type 111 [ST-111]), with a median of 24.9 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (range, 8 to 48 SNPs). The ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam resistance was likely linked to the same G183D substitution in the chromosome-encoded cephalosporinase. Our results suggest that resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam in P. aeruginosa might occur in vivo upon treatment through an amino acid substitution in the intrinsic AmpC leading to ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam resistance, accompanied by resensitization to piperacillin-tazobactam and carbapenems.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes more than 51,000 health care-associated infections per year in the United States, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1). This Gram-negative extracellular pathogen is mostly reported in health care-associated infections in immunocompromised patients. These infections are diverse, ranging from urinary tract infections, acute pulmonary infections, wound infections, acute otitis, and septicemia (2). P. aeruginosa is also the major cause of chronic infection in cystic fibrosis patients (3). In 2017, the World Health Organization included P. aeruginosa in its list of pathogens of global concern, mostly due to the dissemination of multidrug-resistant isolates in this species (4). Although extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (mostly VIM and IMP) are increasingly reported worldwide (5, 6), multidrug resistance (MDR) in P. aeruginosa often involves an association of intrinsic mechanisms. Indeed, P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to many antimicrobials through the constitutive expression of several efflux pumps, low permeability of the outer membrane, and (over)production of the chromosome-encoded cephalosporinase (PDC) (7). Recently, ceftolozane was commercialized in association with tazobactam for the treatment of urinary tract and intra-abdominal severe infections. This association is particularly efficient in P. aeruginosa MDR isolates (8–10). Indeed, ceftolozane is not affected by decreased outer membrane permeability that results in carbapenem resistance (OprD mutations and MexAB-OprM efflux), and it possesses improved stability toward the intrinsic AmpC compared to the other β-lactams (e.g., ceftazidime) (11).

Although resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam (C-T) has been described in vitro (12–14), the development of resistance in vivo has been rarely reported (10, 15–18).

Here, we describe the evolution of resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, and carbapenems of P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from the same patient during recurrent infections over 2.5 years.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

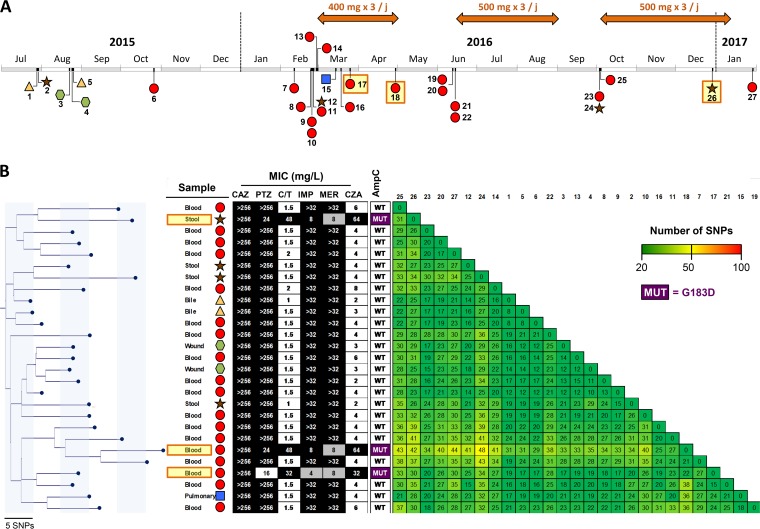

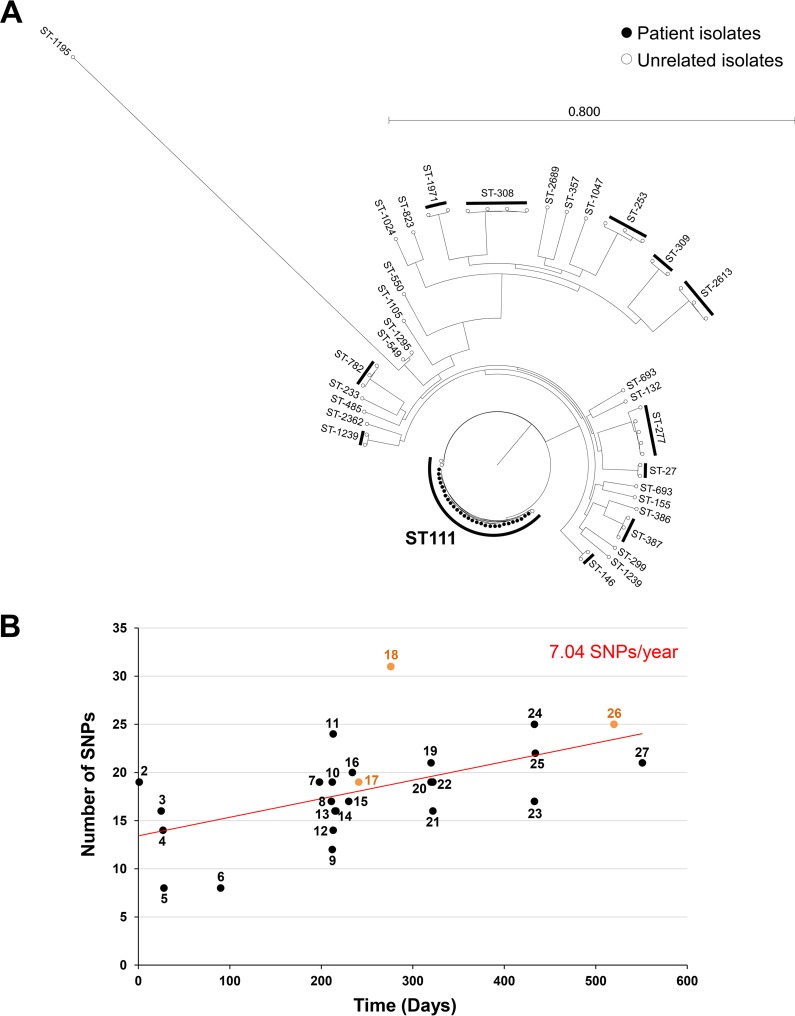

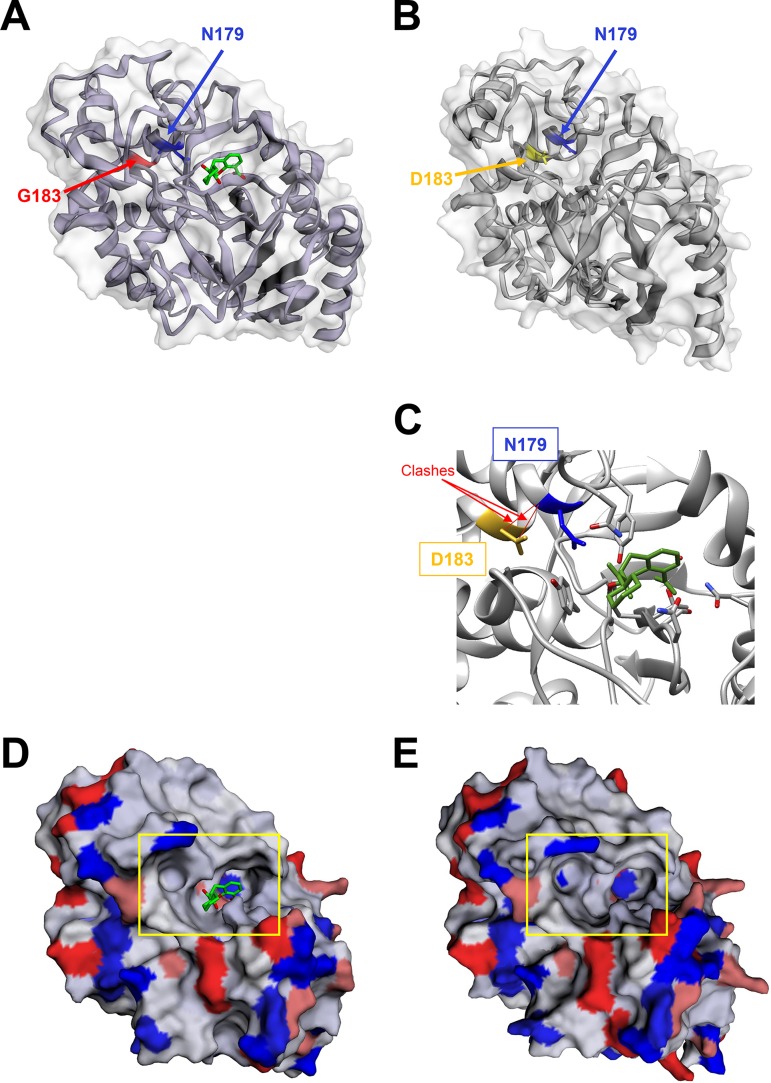

A 3-year-old patient with biliary atresia was liver transplanted twice. Following the second surgery, the patient was treated by colistin (intravenous [i.v.] for 7 days plus aerosol for 14 days) for a ventilator-acquired pneumonia caused by an extremely drug-resistant (XDR) P. aeruginosa isolate susceptible to polymyxins only (MIC, 1 mg/liter). During the next 6 months, four episodes of catheter-related bacteremia caused by ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae were efficiently treated by imipenem and amikacin and catheter ablation. During the same time, the patient remained colonized with the XDR P. aeruginosa isolate which was cultivated from bile (strains 1 and 5), stool (strain 2), and wound (strains 3 and 4) samples (Fig. 1A). In March 2016, C-T (400 mg/kg of body weight, 3 times per day) was introduced for the treatment of a bacteremia caused by the XDR P. aeruginosa (strains 7 to 11) (Fig. 1A), related to the Gore-Tex graft infection used for replacement of the vena cava. This uncommon dosage corresponds to an adaptation to the patient weight compared to that with adults. After 22 days of therapy with C-T, the first C-T-resistant isolate was recovered from blood culture (strain 17). During the following year, two other bacteremias caused by the XDR P. aeruginosa isolate were successfully treated by C-T (500 mg/kg, 3 times per day). Among these 53 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates recovered over a 2.5-year period, three were found to be resistant to C-T, ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA), and ceftazidime (CAZ) (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, partial restoration of piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) and carbapenem (imipenem and meropenem) susceptibilities was observed in these C-T- and CZA-resistant isolates (Fig. 1B). To decipher if the three C-T-resistant isolates derived from a previously C-T-susceptible P. aeruginosa isolate and to potentially identify the resistance mechanism involved in this phenotype, 27 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (including the 3 C-T-resistant isolates) recovered from diverse samples (n = 4 from stool, n = 2 from wound, n = 2 from bile, n = 1 from bronchial aspirate fluid, and n = 18 from positive blood cultures) covering the 2.5-year period were randomly selected and whole-genome sequenced using Illumina technology. De novo assembly and read mappings were performed using CLC Genomics Workbench v10.1 (Qiagen, Les Ulis, France). Multilocus sequence typing derived from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data demonstrated that all of the 27 XDR P. aeruginosa isolates were from the same sequence type (ST), ST-111 (Fig. 2A). The phylogenetic tree and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) count demonstrated that all of these 27 isolates belonged to the same clone, with a median of 24.9 SNPs (range, 8 to 48 SNPs) based on whole-genome SNP analysis (Fig. 1B). Overall, the evolution scale of this clone is of 7.04 SNPs per year (Fig. 2B). In all of the 27 P. aeruginosa isolates (resistant and susceptible isolates), blaOXA-9 and blaOXA-395 genes were identified as acquired resistance genes. Accordingly, the production of OXA-9 and OXA-395 is not supposed to play a role in C-T resistance. Of note, only OXA-539 and GES-6 were previously described to be involved in resistance to C-T (15, 19). In addition, WGS sequencing data identified only one SNP that was common to all C-T-resistant isolates but absent in all susceptible strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This SNP resulted in a substitution of an aspartic acid to a glycine at the position 183 (G183D) of the intrinsic cephalosporinase PDC. Previously, Cabot et al. demonstrated that this mutation might appear in vitro in a P. aeruginosa mutator background and be responsible for high-level resistance to C-T associated with a reduction in the imipenem MIC (14). This particular substitution was also demonstrated in vitro to be responsible for a 16-fold elevation of the CZA MIC values (20). Of note, in our study, the three C-T-resistant isolates that harbor this G183D mutation in PDC were resistant to CZA (8- to 128-fold increase in the MIC) but displayed a partial restoration of imipenem and meropenem (MIC, 4 to 8 mg/liter in C-T-susceptible isolates versus >32 mg/liter in C-T-resistant strains) and TZP (MIC, 16 to 24 mg/liter in C-T-susceptible isolates versus >256 mg/liter in C-T-resistant strains) susceptibilities (Fig. 1B). In our collection, carbapenem resistance results in an OprD porin deficiency due to a frameshift in the oprD gene (Fig. S1) and the hydrolytic activity of the intrinsic AmpC. Accordingly, the partial restoration of carbapenem and TZP susceptibility is likely caused by the decreased hydrolytic activity of the mutated AmpC toward carbapenems and TZP compared to the wild-type enzyme. Accordingly, the specific hydrolysis activity toward piperacillin was of 5.0 mU/mg of proteins for C-T-susceptible isolates versus no detectable hydrolysis activity for the three C-T-resistant isolates. This phenomenon has been previously identified for CMY-2 and ADC-7 (21, 22). Of note, resistance to CZA (caused by increased hydrolytic activity toward CAZ) accompanied by resensitization to carbapenems was recently reported with two variants of KPC carbapenemases. Indeed, it was demonstrated that the catalytic efficiencies of KPC-28 and KPC-14 were 10-fold lower for carbapenems and 10- to 30-fold higher for CAZ than those obtained for wild-type enzymes KPC-2 and KPC-3, respectively (23). Accordingly, a comparison of the wild-type (24) with G183D mutant PDC of Pseudomonas aeruginosa indicates a conformational change of the catalytic pocket that likely is involved in the observed phenotype (Fig. 3). Indeed, we could observe an opening of the catalytic cavity which might help better accommodate large molecules such as ceftolozane and ceftazidime. In the same time, we observed the appearance of a negative charge in the catalytic site (Fig. 3D and E), along with clashes between D183 and N179 (Fig. 3C) that are involved in stabilization of the substrate in the binding pocket of the enzyme.

FIG 1.

(A) Time schedule of the 27 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates that were selected for whole-genome sequencing. Ceftolozane-tazobactam treatment is indicated with an orange arrow over the time schedule. Ceftolozane-tazobactam-resistant isolates (17, 18, and 26) are highlighted in yellow. Types of clinical samples are indicated by different colored shapes (yellow triangle, bile; brown star, stool; green hexagon, wound; red circle, blood; blue square, pulmonary sample). (B) Phylogenetic relationship of the 27 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates (all ST-111). The tables next to phylogenetic tree correspond to (i) MICs to ceftazidime (CAZ), piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP), ceftolozane-tazobactam (C-T), imipenem (IMP), meropenem (MEM), and ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA), the background corresponds to the susceptibility categorization according to EUCAST breakpoints (black for resistant, gray for intermediate, and white for susceptible), (ii) the status of the intrinsic cephalosporinase (AmpC), wild type (WT) or G183D mutant (MUT), and (iii) the matrix of SNP numbers.

FIG 2.

(A) Phylogenetic relationships and sequence types of the 27 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates with P. aeruginosa genomes from the GenBank database. (B) Evolution rates of the ST-111 P. aeruginosa clone (27 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates). Each point corresponds to one P. aeruginosa clinical isolate. The first isolate was used as a reference. The numbers correspond to the isolate number indicated in Fig. 1. Ceftolozane-tazobactam-resistant isolates are indicated in orange. The red curve corresponds to the tendency curve. The evolution rate (indicated in red) corresponds to the slope of the tendency curve.

FIG 3.

(A to E) Comparison of three-dimensional (3D) structures of the wild-type (A and D) and G183D mutant (B, C, and E) PDC β-lactamase. The wild-type PDC corresponds to the 6I30 PDB crystal structure of the AmpC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in complex with bicyclic boronate, as described by Cahill et al. (24). (C) The clashes between D183 and N179 in the mutated PDC are indicated in red. (D and E) Surface charges of the wild-type (D) and G183D mutant (E) PDC β-lactamase. The 3D structure of G183D mutant PDC was modeled using the Phyre2 software (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index). Both 3D structure visualizations were performed using the EzMol 2.1 software (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/).

In addition, our evolutionary analysis showed that this particular substitution occurred three times independently (Fig. 1B). These results might indicate that the G183 position of the P. aeruginosa PDC might be a preferential hot spot mutation site under C-T-selective pressure. Accordingly, the emergence of the same substitution in two C-T-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from a patient who was treated for 42 days with this antimicrobial agent for a recurrent wound infection corroborates our hypothesis (17). In our case, C-T resistance occurred more rapidly (22 days versus 42 days).

Globally, our results suggest that C-T therapy might result in the development of resistance by a single mutation in the intrinsic cephalosporinase PDC within 3 weeks. This single G183D mutation is responsible for resistance to C-T but also to CZA. This substitution seems to result in decreased hydrolytic activity toward TZP but also to carbapenems, thus restoring a potential alternative therapy in the absence of other carbapenem resistance mechanisms (here, deficiency of the OprD porin). It also paves the way for a potential benefit of C-T and carbapenem association for the treatment of difficult-to-treat infection caused by XDR P. aeruginosa that required prolonged therapy. Indeed, this kind of unusual association might prevent the development of resistance to C-T upon treatment. However, in endovascular graft infection, biofilm formation might also play a significant role that should be considered (25). Finally, we should also acknowledge that the low C-T dosage, which was empirically adapted to the weight of the patient, might have been not effective enough to clear the infection and prevent mutant formation. However, no blood dosage was available at the time of this clinical case.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

P. aeruginosa clinical isolates.

Over 2.5 years, 53 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates were collected from stools (n = 10), positive blood cultures (n = 23), bronchial aspirate fluid (n = 5), wounds (n = 5), ascites (n = 1), bile (n = 8), and urine (n = 1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (Bio-Rad, Marnes-La-Coquette, France) and interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines updated in 2019 (http://www.eucast.org/). MICs to ceftolozane-tazobactam (C-T), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA), and piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) were determined using the Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and interpreted according to EUCAST breakpoints updated in 2019 (http://www.eucast.org/). MICs to colistin were determined by broth microdilution (Sensititre/Thermo Fisher), as recommended by EUCAST guidelines.

DNA extraction and sequencing.

Total DNA was extracted from colonies using the UltraClean microbial DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Ozyme, Saint-Quentin, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentrations and purity assessments were determined using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer using the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) HS and/or BR assay kit and NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Saint-Herblain, France). The DNA library was prepared using the Nextera XT v2 kit (Illumina, Paris, France) and then run on NextSeq 500 automated system (Illumina), using a 2 × 100-bp paired-end approach.

Bioinformatic analysis.

De novo assembly and read mappings were performed using CLC Genomics Workbench v10.1 (Qiagen, Les Ulis, France). The acquired antimicrobial resistance genes were identified using the ResFinder server v3.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/). MLST was performed using the MLST 1.8 server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/pMLST/). Phylogeny was performed using the CSI Phylogeny v1.4 server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CSIPhylogeny/) set with default parameters (10× coverage at SNP position, 10% relative depth at SNP position, and 10-bp distance between SNPs) and visualized using the FigTree software v1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Hydrolysis analysis.

The specific activities toward piperacillin of the wild-type and the G183D mutated PDC were determined using the supernatant of a whole-cell crude extract obtained from an overnight culture of C-T-resistant and C-T-susceptible P. aeruginosa clinical isolates with the UV spectrophotometer Ultrospec 2000 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as previously described (26).

Data availability.

The whole-genome sequences generated in the study have been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers detailed in Table S2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pasteur International Bioresources Networking (PibNet, Paris, France) for providing whole-genome sequencing facilities.

This work was partially funded by the University Paris-Sud, France. L.D. and T.N. are members of the Laboratory of Excellence in Research on Medication and Innovative Therapeutics (LERMIT) supported by a grant from the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-LABX-33).

We declare no competing interests.

T.B. and L.D. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. L.D. and T.N. developed the study concept and design. All authors were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of the data. T.B. and L.D. drafted the manuscript. L.D. and T.N. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01637-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stryjewski M, Sexton D. 2003. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in specific types of patients and clinical settings, p 1–15. In Hauser AR, Rello J (ed), Severe infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Perspectives on critical care infectious diseases. Springer US, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lund-Palau H, Turnbull AR, Bush A, Bardin E, Cameron L, Soren O, Wierre-Gore N, Alton EW, Bundy JG, Connett G, Faust SN, Filloux A, Freemont P, Jones A, Khoo V, Morales S, Murphy R, Pabary R, Simbo A, Schelenz S, Takats Z, Webb J, Williams HD, Davies JC. 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis: pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Expert Rev Respir Med 10:685–697. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2016.1177460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. 2017. Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259462/9789241550178-eng.pdf?sequence=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta V. 2008. Metallo-β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species. Expert Opin Invest Drugs 17:131–143. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesaros N, Nordmann P, Plesiat P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Van Eldere J, Glupczynski Y, Van Laethem Y, Jacobs F, Lebecque P, Malfroot A, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin Microbiol Infect 13:560–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Zowalaty ME, Al Thani AA, Webster TJ, El Zowalaty AE, Schweizer HP, Nasrallah GK, Marei HE, Ashour HM. 2015. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: arsenal of resistance mechanisms, decades of changing resistance profiles, and future antimicrobial therapies. Future Microbiol 10:1683–1706. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassetti M, Castaldo N, Cattelan A, Mussini C, Righi E, Tascini C, Menichetti F, Mastroianni CM, Tumbarello M, Grossi P, Artioli S, Carannante N, Cipriani L, Coletto D, Russo A, Digaetano M, Losito AR, Peghin M, Capone A, Nicole S, Vena A, CEFTABUSE Study Group. 2019. Ceftolozane/tazobactam for the treatment of serious Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a multicentre nationwide clinical experience. Int J Antimicrob Agents 53:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortridge D, Duncan LR, Pfaller MA, Flamm RK. 2019. Activity of ceftolozane-tazobactam and comparators when tested against Gram-negative isolates collected from paediatric patients in the USA and Europe between 2012 and 2016 as part of a global surveillance programme. Int J Antimicrob Agents 53:637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haidar G, Philips NJ, Shields RK, Snyder D, Cheng S, Potoski BA, Doi Y, Hao B, Press EG, Cooper VS, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2017. Ceftolozane-tazobactam for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: clinical effectiveness and evolution of resistance. Clin Infect Dis 65:110–120. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda S, Ishii Y, Hatano K, Tateda K, Yamaguchi K. 2007. Stability of FR264205 against AmpC β-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents 30:443–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes MD, Taracila MA, Rutter JD, Bethel CR, Galdadas I, Hujer AM, Caselli E, Prati F, Dekker JP, Papp-Wallace KM, Haider S, Bonomo RA. 2018. Deciphering the evolution of cephalosporin resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 9:e02085-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02085-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berrazeg M, Jeannot K, Ntsogo Enguéné VY, Broutin I, Loeffert S, Fournier D, Plésiat P. 2015. Mutations in β-lactamase AmpC increase resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates to antipseudomonal cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6248–6255. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabot G, Bruchmann S, Mulet X, Zamorano L, Moya B, Juan C, Haussler S, Oliver A. 2014. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ceftolozane-tazobactam resistance development requires multiple mutations leading to overexpression and structural modification of AmpC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3091–3099. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02462-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraile-Ribot PA, Mulet X, Cabot G, Del Barrio-Tofino E, Juan C, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2017. In vivo emergence of resistance to novel cephalosporin-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations through the duplication of amino acid D149 from OXA-2 β-lactamase (OXA-539) in sequence type 235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01117-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01117-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangcuangco LM, Clark P, Stewart C, Miljkovic G, Saul ZK. 2016. Persistent bacteremia from Pseudomonas aeruginosa with in vitro resistance to the novel antibiotics ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam. Case Rep Infect Dis 2016:1520404. doi: 10.1155/2016/1520404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacVane SH, Pandey R, Steed LL, Kreiswirth BN, Chen L. 2017. Emergence of ceftolozane-tazobactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa during treatment is mediated by a single AmpC structural mutation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01183-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01183-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munita JM, Aitken SL, Miller WR, Perez F, Rosa R, Shimose LA, Lichtenberger PN, Abbo LM, Jain R, Nigo M, Wanger A, Araos R, Tran TT, Adachi J, Rakita R, Shelburne S, Bonomo RA, Arias CA. 2017. Multicenter evaluation of ceftolozane/tazobactam for serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 65:158–161. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirel L, Ortiz De La Rosa JM, Kieffer N, Dubois V, Jayol A, Nordmann P. 2019. Acquisition of extended-spectrum β-lactamase GES-6 leading to resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam combination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e01809-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01809-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lahiri SD, Walkup GK, Whiteaker JD, Palmer T, McCormack K, Tanudra MA, Nash TJ, Thresher J, Johnstone MR, Hajec L, Livchak S, McLaughlin RE, Alm RA. 2015. Selection and molecular characterization of ceftazidime/avibactam-resistant mutants in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains containing derepressed AmpC. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1650–1658. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skalweit MJ, Li M, Conklin BC, Taracila MA, Hutton RA. 2013. N152G, -S, and -T substitutions in CMY-2 β-lactamase increase catalytic efficiency for cefoxitin and inactivation rates for tazobactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1596–1602. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01334-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skalweit MJ, Li M, Taracila MA. 2015. Effect of asparagine substitutions in the YXN loop of a class C β-lactamase of Acinetobacter baumannii on substrate and inhibitor kinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1472–1477. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03537-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oueslati S, Iorga BI, Tlili L, Exilie C, Zavala A, Dortet L, Jousset AB, Bernabeu S, Bonnin RA, Naas T. 2019. Unravelling ceftazidime/avibactam resistance of KPC-28, a KPC-2 variant lacking carbapenemase activity. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:2239–2246. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cahill ST, Tyrrell JM, Navratilova IH, Calvopina K, Robinson SW, Lohans CT, McDonough MA, Cain R, Fishwick CWG, Avison MB, Walsh TR, Schofield CJ, Brem J. 2019. Studies on the inhibition of AmpC and other β-lactamases by cyclic boronates. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 1863:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domitrovic TN, Hujer AM, Perez F, Marshall SH, Hujer KM, Woc-Colburn LE, Parta M, Bonomo RA. 2016. Multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing prosthetic valve endocarditis: a genetic-based chronicle of evolving antibiotic resistance. Open Forum Infect Dis 3:ofw188. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dortet L, Oueslati S, Jeannot K, Tande D, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2015. Genetic and biochemical characterization of OXA-405, an OXA-48-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase without significant carbapenemase activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3823–3828. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05058-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The whole-genome sequences generated in the study have been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers detailed in Table S2.