LETTER

MacConkey agar is one of the earliest and most common bacteriological media used in clinical microbiology for the isolation and identification of Gram-negative bacteria (1–3). The medium has been listed as an aerobic medium for use with a wide range of clinical specimens (4), and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommends that MacConkey agar plates be incubated under aerobic conditions (5). However, from an informal survey of microbiology technologists from different countries, we noted that some laboratories use aerobic conditions irrespective of specimen type, while other laboratories use a 5% CO2-enriched environment, particularly for specimens such as respiratory, sterile body fluid, tissue, and wound specimens. The rationale for using the 5% CO2-enriched environment is for workflow optimization, in that technologists can collect all plates (e.g., blood, chocolate, and MacConkey) from the same incubator and read all plates from the same sample together. Also, incubation of MacConkey agar with ∼5% CO2 (or in a candle jar) is recommended in the World Health Organization (WHO) manual for the diagnosis of meningitis when Gram-negative bacteria are suspected in blood cultures, which is inconsistent with CLSI and manufacturer recommendations (6). Experimental data on the growth of Gram-negative bacteria on MacConkey plates under aerobic versus CO2-enriched conditions are not readily available in the literature. The only evidence available is a reference to an abstract presented at the 79th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Microbiology in 1979 (7, 8), which is not publicly available. In order to generate empirical evidence to inform our laboratory procedures, we compared the growth and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of a set of reference strains of clinically significant Gram-negative bacterial species on MacConkey agar plates incubated with either 5% CO2 or ambient air. Furthermore, a total of 101 original and 26 simulated urine samples were also cultured under both conditions, and the results were compared (see the Methods in the supplemental material).

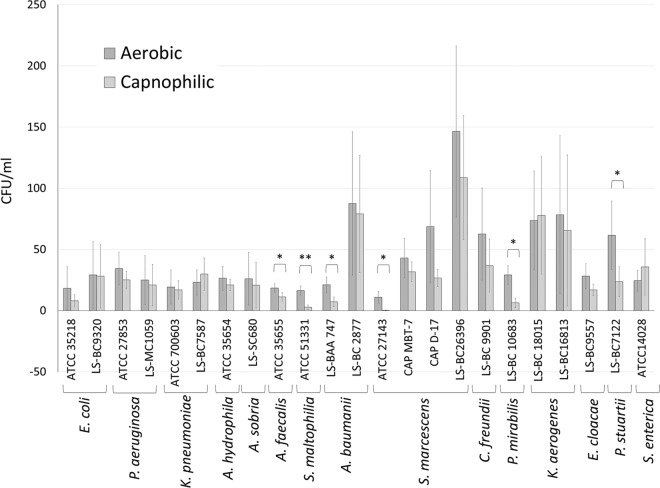

For the majority of the reference bacterial strains tested, colony counts for individual species were not significantly different when grown under 5% CO2 instead of aerobic conditions, but the overall average colony count of all the bacterial species was higher on the aerobic plates (P < 0.0001). Colony counts were significantly higher (2- to >50-fold) for some strains of Alcaligenes faecalis, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, and Providencia stuartii (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). For Serratia marcescens (ATCC 27143), colonies were only observed after 48 h of incubation under CO2-enriched growth conditions. For Proteus mirabilis, swarming was only observed under aerobic conditions. Also, the Providencia stuartii and Salmonella enterica colony diameters were much larger under aerobic conditions than under CO2-enriched conditions. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) profiles of bacteria grown under aerobic or CO2-enriched conditions were mostly identical or had insignificant differences (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Quantitative culture of clinically significant Gram-negative bacteria grown under aerobic versus CO2-enriched growth conditions. Bacterial strains were grown (in duplicate) on MacConkey agar plates with either 5% CO2 or ambient air, and bacterial colonies were counted, as described in the text. The results represent mean ± standard error mean (n = 3 independent studies). Statistical significance (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) is based on a 2-tailed, pairwise Student's t test. E. coli, Escherichia coli; P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; A. hydrophila, Aeromonas hydrophila; A. sobria, Aeromonas sobria; A. faecalis, Alcaligenes faecalis; S. maltophilia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; A. baumannii, Acinetobacter baumannii; S. marcescens, Serratia marcescens; C. freundii, Citrobacter freundii; P. mirabilis, Proteus mirabilis; K. aerogenes, Klebsiella aerogenes; E. cloacae, Enterobacter cloacae; P. stuartii, Providencia stuartii; S. enterica, Salmonella enterica; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CAP, College of American Pathologists; LS, laboratory strains.

Urine culture plates are recommended to be incubated in a non-CO2 incubator, with the exception of the Gram-positive coccobacillus Actinobaculum schaalii, a common uropathogen in children and the elderly (4). However, there are no associated data to support the aerobic incubation of urine culture plates. Therefore, to compare bacterial growth from urine samples under CO2-enriched versus aerobic conditions, a total of 127 urine specimens were tested, including 26 simulated specimens (Table 1). Simulated specimens were created to increase the diversity of clinically significant Gram-negative bacterial species in our specimen set. After 24 h of incubation, bacteria were detected from a total of 68 specimens when the MacConkey plates were grown under aerobic conditions, as opposed to 67 specimens under CO2-enriched conditions. None of the specimens yielded a higher bacterial count when grown under CO2-enriched conditions than when grown under aerobic conditions. Bacterial counts were categorically (see Methods in the supplemental material) higher in 12 (9.4%) specimens when grown under aerobic versus CO2-enriched conditions. However, clinically significant differences were observed in 4 (3.1%) specimens. Three of these specimens grew Klebsiella pneumoniae and one grew Acinetobacter lwoffii, with bacterial counts of 10,000 to 50,000 CFU/ml in an aerobic environment. However, the bacterial counts in these specimens were <10,000 CFU/ml under 5% CO2 and would have been reported as insignificant results.

TABLE 1.

Summary of urine culture results

| Culture category | No. (% of total [n = 127]) by environment |

|

|---|---|---|

| O2 (aerobic) | CO2 enriched | |

| Patient specimens | 101 (79.5) | 101 (79.5) |

| Simulated urine specimens | 26 (20.4) | 26 (20.4) |

| Bacterial count (CFU/ml) of: | ||

| >100,000 | 42 (33.1) | 39 (30.7) |

| 50,000–100,000 | 5 (3.9) | 6 (4.7) |

| 10,000–50,000 | 15 (11.8) | 10 (7.9) |

| <10,000 | 6 (4.7) | 12 (9.4) |

| Specimens showing no growth | 59 (46.4) | 60 (47.2) |

| Urine culture with clinically significant results | 54 (42.5) | 50 (39.4) |

Instead of splitting different plates into aerobic and CO2-enriched environments, some laboratories have chosen to use only CO2-enriched conditions for workflow convenience. This has been justified by a belief that the differences in growth and antibiotic susceptibility may not be clinically significant for most bacteria. However, our findings show that there can be clinically significant differences in some situations and that the incubation of MacConkey plates under CO2-enriched conditions may decrease the sensitivity of the test for certain organisms. Therefore, our data emphasize the importance of adherence to aerobic conditions when growing bacteria on MacConkey agar plates.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01441-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.MacConkey AT. 1900. Note on a new medium for the growth and differentiation of the Bacillus coli communis and the Bacillus typhi abdominalis. Lancet 156:20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)99513-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacConkey A. 1905. Lactose-fermenting bacteria in faeces. J Hyg (Lond) 5:333–379. doi: 10.1017/s002217240000259x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mossel DA, Mengerink WH, Scholts HH. 1962. Use of a modified MacConkey agar medium for the selective growth and enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae. J Bacteriol 84:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McElvania E, Singh K. 2019. Specimen collection, transport, and processing: bacteriology, p 228–271. In Carroll KC, Pfaller MA, Landry ML, McAdam AJ, Patel R, Richter S, Warnock DW (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 12th ed, vol 1. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2004. Quality control of commercially prepared microbiological culture media; approved standard, 3rd ed. CLSI document M22-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. 2011. Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae: WHO manual. 2nd ed. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70765/WHO_IVB_11.09_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazura-Reetz G, Neblett TR, Galperin JM. 1979. MacConkey agar: CO2 vs. ambient incubation. Abstr 79th Ann Meet Am Soc Microbiol, Los Angeles, CA, 4 to 8 May 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becton Dickinson GmbH. 2013. BD MacConkey II agar. Becton Dickinson GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany: http://legacy.bd.com/resource.aspx?IDX=8978. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.