Background

The impact of clinical trials on treatment advances in cancer is diminished by suboptimal trial participation both by patients and among clinicians and their organizations. Nearly one half (40%) of National Clinical Trial Network (formerly Cooperative Group Program) trials fail to complete accrual,1 and less than 2% of adults with cancer enroll in trials.2,3 Last year, no trials were offered in 36% of physician-owned, 14% of hospital/health system–owned, and 3% of academic practices.4 Little progress has been made in identifying multipronged strategies5,6 to improve the clinical trials process.

Trial accrual is complex and involves several steps. Factors that impede accrual, such as long delays in designing and initiating trials, patient barriers, and regulatory burden, have been studied independently7,8 but must be understood collectively to improve the entire accrual process. As part of a larger effort to understand clinical trial accrual,9 we conducted semistructured telephone interviews with clinical trial stakeholders. We first identified key leaders from the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program and used snowball sampling to identify other community and academic stakeholders with the goal of achieving representation from individuals in various leadership roles and from a variety of geographic areas. Our 10 interviews represent stakeholders from nine states (Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Texas, North Dakota, and Virginia) and with diverse experience. Stakeholders were network leaders (clinical practice administrator, medical doctor) and administrators (medical doctor; two registered nurses, oncology nurse certified) in community oncology practice, oncology professional associations, and industry-sponsored and cooperative group programs. Interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes (led by S.J.C.L.), and six stakeholders provided additional materials and written commentary by follow-up e-mail.

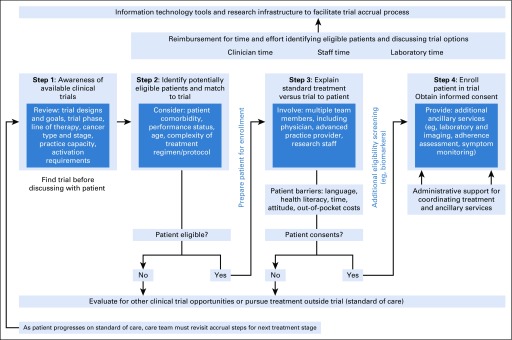

We conducted a thematic analysis of interview content and identified four major steps involved in clinical trial accrual. These steps, depicted in the resulting conceptual model shown in Figure 1, are (1) promoting awareness of available trials, (2) identifying eligible patients, (3) explaining standard treatment and trial options to patients, and (4) completing enrollment. Stakeholders emphasized that completion of all steps in the accrual process requires coordination of care and transfer of responsibility among care teams (eg, physicians, nurses, and research staff). They also identified potential solutions for overcoming barriers associated with each step. The model illustrates practice structure, reimbursement mechanisms, and electronic health information technology tools that can be incorporated into clinical care and inform best practice.

FIG 1.

Process model that describes the steps of cancer clinical trial accrual.

Step 1: Promote Available, Open Clinical Trials

The trial accrual process begins with a clinician’s awareness of available trials, which requires familiarity with trial types and goals, patient mix in the practice, and differences between trial phases (eg, dose escalation v comparison with standard treatment). Stakeholders interviewed noted that whether a practice has capacity to activate and administer a trial depends on available infrastructure, including workforce, capability in laboratory and pathology processing, and partnerships with other oncology practices (ie, to refer patients to trials at nearby practices). Practice administrators, in particular, reported that the time involved for contract and budget negotiation often limits their ability to offer trials,7 coverage analysis for industry-sponsored trials is costly and inefficient, and successful accrual to trials requires staff time and resources for keeping providers knowledgeable about available trials before discussing with patients. These challenges can impede or delay trial activation and affect patient accrual downstream.

Potential solutions offered for enhancing awareness of trials both ongoing and upcoming included information technology tools, such as central registration platforms and trial management software, and systematic identification of open trials within and across practices. Although these tools exist for most National Clinical Trial Network–sponsored trials, their availability for industry-sponsored trials or internally among practices varies. Because a range of research team members complete contract negotiation and coverage analysis tasks, standardized training could ensure knowledge of trials and ancillary services across practices. Stakeholders noted that especially among smaller practices, promotion of available trials may mean the referral of patients to ostensible competitors. Affiliation with contracted networks, such as Sarah Cannon or The US Oncology Network, presents a collaborative alternative but may introduce other trade-offs (eg, constraints to autonomy).

Step 2: Identify Potentially Eligible Patients and Match to Trial

Interviews found that systematic identification and matching of eligible patients to trials are a major challenge to accrual. A designated person (eg, physician, advanced practice provider, nurse, or research staff) may need to review patient lists to determine eligibility and select available and open trials. This step can involve at least three tasks: reviewing eligibility, preferably before patient appointments; determining whether patients are eligible for available trials; and documenting eligibility assessment as part of the medical record.

Eligibility assessments must consider patient comorbidity, performance status, age, and complexity of treatment regimen and protocol. Stakeholders noted that because treatments are increasingly selected on the basis of genetic mutations present in tumors, eligibility for trials has become less straightforward. Thus, although the numbers of trials are growing, particularly in industry, stringent eligibility specifications that are based on tumor type and genomic markers have increased the burden of identifying patients, each of whom may be eligible for fewer and fewer trials.10-18 For some rare tumor subtypes, only tumor-agnostic phase I trials may be available, whereas there might be more phase II and III trial options for patients with more common tumor subtypes.

As a potential solution to facilitate systematic identification and matching of eligible patients, stakeholders again emphasized the importance of electronic tools, in this case clinical decision support for treatment pathways.19-22 Oncologists’ willingness to adopt these tools may promote efficiency of this task. To that end, the National Cancer Institute National Community Cancer Centers Program has created a self-assessment tool to enable administrators to identify gaps in practice capacity and then to benchmark and strengthen their trial infrastructure.23

Step 3: Explain Standard Treatment Versus Trial to Patient

The third major step in the trial accrual process is discussion with patients—the fundamental process of achieving informed consent. In their interviews, stakeholders emphasized the importance of explaining direct versus indirect benefits (which may vary by trial design) and noted that even when patients are identified as eligible, barriers to participation still exist. Extensively documented in the literature, these barriers to participation include language, health literacy, time, attitude toward trials, and prohibitive out-of-pocket costs.8 Because of trial complexities and these potential barriers, communication skills are essential. Potential solutions may include additional training to enhance discussion of risks and benefits and goals of care for patients who are considering participation in clinical trials. Indeed, research has shown that consent to participation is positively correlated with the consenter’s level of experience.12,18

Step 4: Enroll Patient in Trial

After obtaining and documenting informed consent, a critical last step of the process is to enroll patients and initiate care per protocol, which often requires clinical services from noncancer care teams. For example, specific laboratory tests (eg, pharmacokinetic or ECG studies common to phase I trials) and imaging may be required to determine response to therapy. This type of monitoring, which historically has not been the purview of oncology clinics and providers, may necessitate interactions with clinicians from different specialties. In addition, addressing supportive care and unique needs related to trial regimens—activities that are not uniformly reimbursed—can introduce additional complexity, even as clinical organizations launch initiatives to provide insurance coverage for all care provided to patients in trials.24 Finally, beyond interactions with other clinical service teams, stakeholders described a lack of administrative support to coordinate therapy and ancillary services. This includes the collection of patient-reported outcomes, management of regulatory requirements, compliance with trial sponsor, site monitoring, regulatory document management, adverse event reporting, and sufficient staffing. Numerous protocol amendments and updates make management tasks iterative, which quickly become overwhelming. Potential solutions to these and other care coordination challenges25 likely will require additional financial resources and infrastructure, as emphasized by community practitioners.

Future Directions and Considerations

Our in-depth interviews with stakeholders identified an entire process associated with clinical trial accrual and multiple challenges associated with each step in that process. Emerging therapeutics and the changing landscape of oncology are introducing multiple new components to quality cancer care, including how a practice stays aware of available clinical trials, identifies eligible patients, introduces standard treatment versus trial participation to those patients, and enrolls and cares for patients throughout the trial. Each step has become increasing complicated in recent years partly because of emerging discoveries that inform precision oncology.26,27 For example, whereas trials were once available for all patients with stage II breast cancer, many protocols now specify evaluation of biomarkers before enrolling patients in trials. After assessing multiple factors that determine eligibility, practices must provide detailed documentation of these in the electronic health record. Because eligibility criteria are becoming more specific and numerous,28 an individual patient’s likelihood of meeting all criteria may simultaneously diminish. Meanwhile, the infrastructure and processes required to open a single trial remain the same regardless of the number of patients enrolled. Because most payment models only reimburse for services rendered after (v before) enrollment, clinicians who invest time and resources to identify eligible participants may jeopardize the financial well-being of their practices. Key solutions and opportunities for policy change may include trial-specific adjustments to reimbursement and incentives for administrative and infrastructure costs.

Advances in clinical science hold great promise for the future of oncology. Cancer therapies can now be evaluated in trials of specific patients most likely to benefit. However, because practices must do more work to make the patient-trial match, their same amount of effort now achieves a lower yield in enrollment. Our next goal must be to work toward the enhancement of logistic, infrastructure, and policy support to translate oncology discoveries to the process of delivering high-quality cancer care, particularly in community settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article was produced by employees of the US government as part of their official duties and, as such, is in the public domain of the United States of America. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (P30CA142543, U54 CA163308-05S1) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001103, C.C.M.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conceptual Model for Accrual to Cancer Clinical Trials

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

David E. Gerber

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Gilead Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Samsung Bioepis, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Speakers’ Bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Immunogen (Inst), ArQule (Inst), ImClone Systems (Inst), BerGenBio (Inst), Karyopharm Therapeutics (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from Oxford University Press for two books, royalties from Decision Support in Medicine for the Clinical Decision Support–Oncology online program.

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly, ArQule, Bristol-Myers Squibb

John V. Cox

Employment: The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Simmons Cancer Center

Leadership: Parkland Health System

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen, Medfusion, Merck, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson

Honoraria: Association of Community Cancer Centers, American College of Physicians, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Cancer Policy Forum

Research Funding: The US Oncology Network

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: American College of Physicians, Association of Community Cancer Centers

Other Relationship: Mary Crowley Research Center, American Society of Clinical Oncology, Texas Oncology Foundation

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mendelsohn J, Moses HL, Nass SJ. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman MA, Cain DF. National Cancer Institute sponsored cooperative clinical trials. Cancer. 1990;65:2376–2382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:10+<2376::aid-cncr2820651504>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2017: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e353–e394. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.020743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denicoff AM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Grubbs SS, et al. The National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Trial Accrual Symposium: Summary and recommendations. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:267–276. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:245–255. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vose JM, Levit LA, Hurley P, et al. Addressing administrative and regulatory burden in cancer clinical trials: Summary of a stakeholder survey and workshop hosted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Association of American Cancer Institutes. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3796–3802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.6781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy CC, Craddock Lee SJ, Geiger AM, et al. Community oncologist and practice barriers to clinical trial accrual. Presented at Translational Science 2019; Washington, DC: March 5-8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smuck B, Bettello P, Berghout K, et al. Ontario protocol assessment level: Clinical trial complexity rating tool for workload planning in oncology clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:80–84. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demmy TL, Yasko JM, Collyar DE, et al. Managing accrual in cooperative group clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2997–3002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasco DW, Xie Y, Yan J, et al. The impact of consenter characteristics and experience on patient interest in clinical research. Oncologist. 2009;14:468–475. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, et al. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: Implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv002. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber DE, Pruitt SL, Halm EA. Should criteria for inclusion in cancer clinical trials be expanded? J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:289–291. doi: 10.2217/cer.15.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber DE, Lakoduk AM, Priddy LL, et al. Temporal trends and predictors for cancer clinical trial availability for medically underserved populations. Oncologist. 2015;20:674–682. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, et al. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, et al. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: Implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:S56–S57. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber DE, Rasco DW, Skinner CS, et al. Consent timing and experience: Modifiable factors that may influence interest in clinical research. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:91–96. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somkin CP, Ackerson L, Husson G, et al. Effect of medical oncologists’ attitudes on accrual to clinical trials in a community setting. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e275–e283. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lidz CW, Benedicto CM, Albert K, et al. Clinical concerns and the validity of clinical trials. AJOB Prim Res. 2013;4:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howerton MW, Gibbons MC, Baffi CR, et al. Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109:465–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson SV, Momperousse D, Leventhal H. Physician perspectives on cancer clinical trials and barriers to minority recruitment. Cancer Contr. 2005;12:93–96. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimond EP, Zon RT, Weiner BJ, et al. Clinical trial assessment of infrastructure matrix tool to improve the quality of research conduct in the community. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:63–64. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.005181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber JS, Levit LA, Adamson PC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: The critical role of phase I trials in cancer research and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:278–284. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmud A, Zalay O, Springer A, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials: A physician survey. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:119–125. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garraway LA, Verweij J, Ballman KV. Precision oncology: An overview. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1803–1805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad V, Fojo T, Brada M. Precision oncology: Origins, optimism, and potential. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia S, Bisen A, Yan J, et al. Thoracic oncology clinical trial eligibility criteria and requirements continue to increase in number and complexity. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1489–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]