Abstract

Background: Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 has been previously reported in the carcinogenesis of several tumors, and its potential functional polymorphisms have also been investigated in various diseases. However, the relationship between these polymorphisms and the susceptibility of thyroid cancer has still been largely unknown. In the present study, we aimed to explore the association between MALAT1 polymorphisms and thyroid cancer (TC) susceptibility, as well as potential biological function in TC.

Methods: We conducted a case-control study with 1134 papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) patients and 1228 controls to evaluate the potential correlation between MALAT1 genetic variations (single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP) and the risk of PTC. More detailed molecular mechanisms were explored by luciferase assay, cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), and flow cytometry.

Results: MALAT1 SNP rs619586 was identified as a significantly protective factor of PTC susceptibility (P = 0.017, OR= 0.76, 95%CI = 0.60-0.95). Further functional experiments of rs619586 indicated that G allele of rs619586 could significantly decrease MALAT1expression, reduce PTC proliferation, and directly increase PTC apoptosis.

Conclusions: Our findings suggested that MALAT1 SNP rs619586 could serve as a potential indicator for PTC susceptibility and pathogenesis.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, long noncoding RNA, MALAT1, polymorphism, susceptibility.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignancy and its incidence has been increasing worldwide over the past decades 1. TC could be classified into papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC), medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), according to their histological characteristics 2. Over 90% of TC cases are PTC and FTC, together known as the well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC). WDTC patients usually have favorable prognosis, and surgery and radio-iodinated therapy are effective treatment for WDTC. The other cases, however, might eventually dedifferentiate, become aggressive and result in fatality 3.

Both genetic and epigenetic alternations have been explored and identified as the potential triggers or regulators of TC pathogenesis, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). SNP is a kind of mispairing or mutation in the genome, comprising at least 1% of the total population 4. Some of SNPs are functional (located in both coding and noncoding regions of the gene) and influence corresponding gene expression via direct or indirect pathways 5-8. In TC, the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK are the crucial signaling pathways, closely associated with the most genetic events during TC occurrence and development. These pathways also play an important role in regulation of cell growth, apoptosis, and survival 9-11. Besides these functional gene-regulatory polymorphisms, other SNPs located in non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) also draw more attention 12-14.

As an important member of ncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified to involve in most processes of tumorigenesis, including cell growth, survival and metastasis. LncRNAs are usually composed with over 200 nucleotides, and they cannot code or translate to the proteins as the final product 15, 16. Also, lncRNAs generally have relatively lower expression quantity, and often dwell in the nucleus. The metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1 (MALAT1) is an 8779 bp transcript 17, which has been reported as a crucial factor in several human diseases, including TC. Also, genetic variants of MALAT1, such as SNPs, have been reported to associate with susceptibility to these diseases 18, 19.

In this study, we have investigated whether certain SNPs on MALAT1 could be potential diagnostic biomarkers for PTC. We evaluated the association between MALAT1 tagSNPs and PTC risk, compared MALAT1 expression levels among different genotypes of these SNPs, and analyzed the functional effects of these SNPs on papillary thyroid carcinogenesis.

Methods and materials

Ethic statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Hospital Affiliated to Guizhou Medical University (No.201674). The corresponding methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All participants in this program received a detailed content of this research and signed a written informed consent form before donating their biological samples.

Study population and participants

We enrolled 1140 PTC patients and 1230 cancer-free controls from the Hospital affiliated to Guizhou Medical University and the Tumor Hospital of Guizhou Province, China, between April 2012 and March 2016. Detailed participants' demographic and clinical information (including age, gender, topography, lymph node, metastasis, and grade) were provided in table 1 20. Age and gender were well matched and indistinguishable between PTC and control groups (P = 0.754 for age and P = 0.846 for gender, respectively). Among of 1140 PTC patients, there were 64 participants who donated their tumor and adjacent normal tissue for the further investigation.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and clinical features

| Variables | Cases (n =1134) | Controls (n = 1228) | Pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age (years) | 0.754 | |||||

| ≤ 45 | 590 | 52.0 | 631 | 51.4 | ||

| > 45 | 544 | 48.0 | 597 | 48.6 | ||

| Sex | 0.846 | |||||

| Male | 355 | 31.3 | 389 | 31.7 | ||

| Female | 779 | 68.7 | 839 | 68.3 | ||

| Topography | ||||||

| T1 | 885 | 78.0 | ||||

| T2 | 138 | 12.2 | ||||

| T3 | 98 | 8.6 | ||||

| T4 | 13 | 1.2 | ||||

| Lymph Node | ||||||

| N0 | 695 | 61.3 | ||||

| N1 | 439 | 38.7 | ||||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| M0 | 1113 | 98.2 | ||||

| M1 | 21 | 1.8 | ||||

| Grade | ||||||

| I + II | 963 | 84.9 | ||||

| III + IV | 171 | 15.1 | ||||

a Two-sided c2 test for the frequency distributions of selected variables between cases and controls.

SNP selection

Potential candidate SNPs on MALAT1 were selected according to the following criteria: 1) locating in MALAT1; 2) acting as tagSNPs; 3) minor allele frequency of each SNP exceeding5% in Han Chinese population; 4) A linkage disequilibrium value of r2< 0.8 for each other. We also added previously reported SNPs on MALAT1 into this study. Four candidate SNPs met these requirements. However, further investigation in Haploview software and 1000 Genomes project demonstrated that the SNPs rs619586 and rs664589 were in complete linkage equilibrium in Chinese. This was confirmed by our genotyping as well. Based on further functional predictions of these two SNPs, we finally includedSNPrs619586 in our study because of its potential regulation in MALAT1 expression.

DNA extraction and polymorphism genotyping

5 ml peripheral venous blood was collected from each participant. QIAcube HT Plasticware and QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT Kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany) were used for DNA extraction, following the manufacturer's protocol. The quality of DNA samples was evaluated based on the corresponding analysis on Nanodrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). Genotyping of lnc MALAT1 polymorphisms was performed in TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay using ABI Fast 7900HT real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer were synthesized and applied by Biolight Tec. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), and all primer and probe sequences were listed in the Supplementary table s1. SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for allelic discrimination. Six samples were placed in each plate as the quality control. Additional10% samples were randomly chosen to repeat the genotyping, and the results were 100% consistent.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then reverse transcribed. The resulting cDNA was used for qPCR in TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) to evaluate the expression of MALAT1 in PTC tissues, and beta-actin was used for normalization as an endogenous control. The results were averaged from three replicates under the same operation and condition.

Cell culture

Culture condition of TPC-1 was described as our previous study 1. And the BCPAP cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and was grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2-O2 mixture.

Plasmids construction and transfection

The total MALAT1 gene (from NC_000011.10) was synthesized and constructed into pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) by Biolight Tec. Company (Nanjing, China) as the MALAT1 expression plasmid, and the single site mutation was used to obtain the mutation plasmid with G allele on rs619586 site. For luciferase reporter plasmids, 1000bp fragments of MALAT1 containing A>G rs619586 polymorphism (500bp upstream and 500bp downstream of rs619586) were synthesized and constructed into pGL3-basic vector(Promega, Madison, WI, USA) by Biolight Tec Company (Nanjing, China). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

For transfection experiments, 1×106 cells were seeded in each well of a 24-well culture plate. The lipofectamine-2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) was used to transfect 0.5μg constructed MALAT1 expression plasmids with different alleles (A and G) on rs619586 site into each well. The eGFP plasmid was co-transfected as the index of transfection efficiency and the internal standard.

Cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was quantified by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8). Cells were cultured in a 96-well plate for transfection with MALAT1 wild type and mutation expression plasmids. After transfection and incubation, CCK-8 reagent was added into each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Absorbance of each well was evaluated at 450nm with a microplate reader. The results were averaged from triplicated readings under the same operation and condition.

Cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) double staining. Because both TPC-1 and BCPAP cell lines did not display the trend of severe apoptosis, we added the cisplatin as the pretreatment to induce the corresponding cellular process. After 24h treatment with MALAT1 expression plasmid and its variants, cells were collected by centrifugation and re-suspended. Annexin V-FITC and PI were then added. Flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, CA, USA) was used to analyze cell apoptosis and calculate the apoptosis rate. Three replications were performed under the same operations and conditions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS software (version 9.13, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Differences between groups were analyzed using Student's t-test. Genotype distribution was analyzed by chi-square test to compare with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Differences between the distributions of demographic and clinical characteristics in PTC patient and control groups were evaluated by Student's t-test or chi-square tests. Logistic regression was performed to analyze the association between MALAT1 polymorphisms and TC risk, adjusted by age, gender, topography, lymph node, metastasis, and tumor grade.

Results

Associations between MALAT1 polymorphism and PTC risk

The distributions of demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were listed in the Table 1. There were no significant differences in gender and age between TC patient and control groups. For TC patients, 78.0%, 12.2%, 8.6% and 1.2% were diagnosed as T1, T2, T3, and T4, respectively. For lymph node metastasis, 61.3% patients were in N0 (with no lymph node metastasis) and the remaining 38.7% were in N1. Furthermore, only 1.8% of TC patients demonstrated distant metastasis in their pathological examinations. In addition, 84.9% patients were diagnosed as early stage (I+II) and 15.1% were in advanced stage (III+IV).

Data from SNP genotyping assays for MALAT1 polymorphisms were shown in table 2. There was statistically significant association between SNP rs619586 and PTC. In the additive model, genotype AG+GG of rs619586showed a protective effect compared with genotype AA (P = 0.017, OR = 0.76, 95%CI = 0.60-0.95). Besides, the dominant and recessive model also displayed their significances in PTC patients (P= 0.017, OR = 0.76, 95%CI = 0.60-0.95 for dominant and P= 0.033, OR = 0.11, 95%CI =0.01-0.84 for recessive model, respectively). There was no significant association between either rs11227209 or rs3200401 and the risk of PTC in the participants.

Table 2.

Genotyping of MALAT1 polymorphisms and their association with thyroid cancer.

| SNPs | Genotypes | Cases | Controls | Pa | Adjusted OR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1134 | % | n = 1228 | % | (95% CI)b | ||||

| rs11227209 | CC | 1042 | 91.97 | 1110 | 90.46 | Reference | ||

| CG | 91 | 8.03 | 110 | 8.96 | 0.389 | 0.88 (0.66-1.18) | ||

| GG | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.57 | 0.962 | NA | ||

| Additive model | 0.09 | 0.79 (0.60-1.04) | ||||||

| Dominant model | 0.196 | 0.83 (0.62-1.10) | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.962 | NA | ||||||

| rs619586 | AA | 1002 | 88.36 | 1051 | 85.59 | Reference | ||

| AG | 131 | 11.55 | 167 | 13.6 | 0.116 | 0.82 (0.64-1.05) | ||

| GG | 1 | 0.09 | 10 | 0.81 | 0.032 | 0.11 (0.01-0.82) | ||

| Additive model | 0.017 | 0.76 (0.60-0.95) | ||||||

| Dominant model | 0.045 | 0.78 (0.61-0.99) | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.033 | 0.11 (0.01-0.84) | ||||||

| rs3200401 | CC | 808 | 71.32 | 872 | 71.18 | Reference | ||

| CT | 302 | 26.65 | 322 | 26.29 | 0.878 | 1.01 (0.84-1.22) | ||

| TT | 23 | 2.03 | 31 | 2.53 | 0.424 | 0.80 (0.46-1.38) | ||

| Additive model | 0.761 | 0.98 (0.83-1.14) | ||||||

| Dominant model | 0.944 | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.411 | 0.80 (0.46-1.37) | ||||||

a Two-sided χ2 test.

b Adjusted for age and sex in logistic regression model.

Stratified analysis of MALAT1 polymorphism in clinical features in PTC

Stratified analysis results were shown in table 3. SNP rs619586 also displayed its significantly protective role in the group with age ≤ 45(P = 0.035, OR = 0.70, 95%CI = 0.50-0.98), male group (P = 0.036, OR = 0.61, 95%CI = 0.39-0.87), and M0 group (patients with no distant metastasis) (P = 0.036, OR = 0.77, 95%CI = 0.60-0.98).

Table 3.

Stratification analysis of MALAT1 rs619586 in thyroid cancer in a dominant model

| Variables | AA (case/control) | AG/GG (case/control) | Pa | Adjusted OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | (95% CI)b | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ≤45 | 523/533 | 88.64/84.47 | 67/98 | 11.36/15.53 | 0.035 | 0.70 (0.50-0.98) | ||

| >45 | 479/518 | 88.05/86.77 | 65/79 | 11.95/13.23 | 0.525 | 0.89 (0.63-1.27) | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 322/333 | 90.70/85.60 | 33/56 | 9.30/14.40 | 0.036 | 0.61 (0.39-0.87) | ||

| Female | 680/718 | 87.29/85.58 | 99/121 | 12.71/14.42 | 0.316 | 0.86 (0.65-1.15) | ||

| Topography | ||||||||

| T1 | 783/1051 | 88.47/85.59 | 102/177 | 11.53/14.41 | 0.054 | 0.77 (0.60-1.01) | ||

| T2 | 121/1051 | 87.68/85.59 | 17/177 | 12.32/14.41 | 0.531 | 0.84 (0.49-1.44) | ||

| T3 | 88/1051 | 89.80/85.59 | 10/177 | 10.20/14.41 | 0.235 | 0.67 (0.34-1.31) | ||

| T4 | 10/1051 | 76.92/85.59 | 3/177 | 23.08/14.41 | 0.403 | 1.74 (0.47-6.43) | ||

| Lymph Node | ||||||||

| N0 | 613/1051 | 88.20/85.59 | 82/177 | 11.80/14.41 | 0.116 | 0.80 (0.60-1.06) | ||

| N1 | 389/1051 | 88.61/85.59 | 50/177 | 11.39/14.41 | 0.104 | 0.76 (0.54-1.06) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||||

| M0 | 985/1051 | 88.50/85.59 | 128/177 | 11.50/14.41 | 0.036 | 0.77 (0.60-0.98) | ||

| M1 | 17/1051 | 80.95/85.59 | 4/177 | 19.05/14.41 | 0.447 | 1.54 (0.51-4.67) | ||

| Grade | ||||||||

| I + II | 851/1051 | 88.37/85.59 | 112/177 | 11.63/14.41 | 0.051 | 0.78 (0.60-1.00) | ||

| III + IV | 151/1051 | 88.30/85.59 | 20/177 | 11.70/14.41 | 0.37 | 0.80 (0.49-1.81) | ||

a Two-sided χ2 test.

b Adjusted for age and sex in logistic regression model.

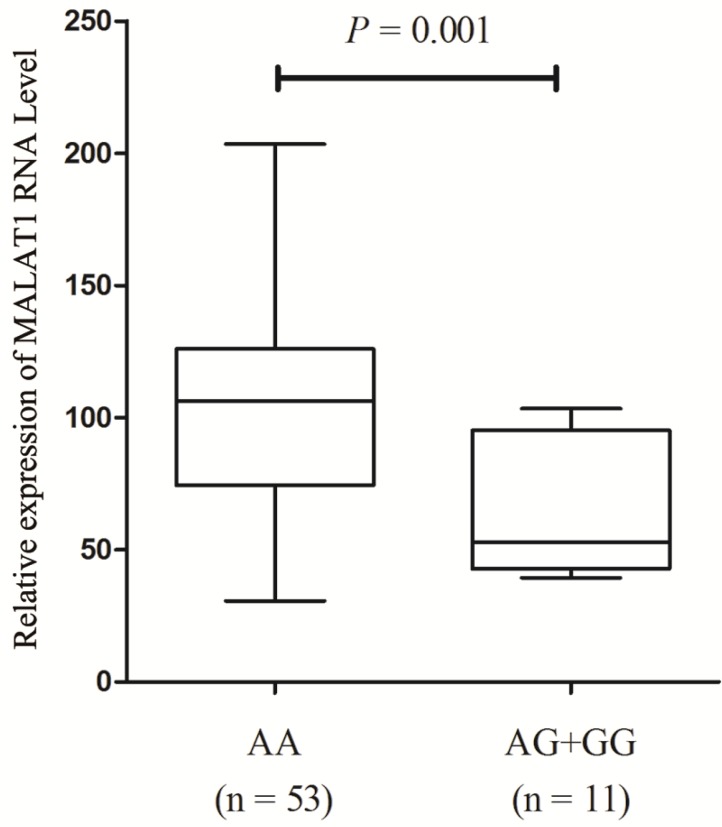

The genotype-phenotype relationship between MALAT1 expression and its polymorphism

We further quantified MALAT1 expression levels in PTC tissue samples with different genotypes of SNP rs619586 in order to investigate the influence of rs619586 variants on MALAT1 transcription. As displayed in figure 1, after standardization by each corresponding normal tissues, the MALT1 expression in patients' tumor tissues displayed higher expressions (Ranging from 5.87 to 201.6 folds). And MALAT1 expression level in samples with AA genotype was significantly higher than those with AG+GG genotypes (P = 0.001, fold change = 1.65).

Figure 1.

Expression of lnc MALAT1 in PTC tissues with different genotypes of rs619586.

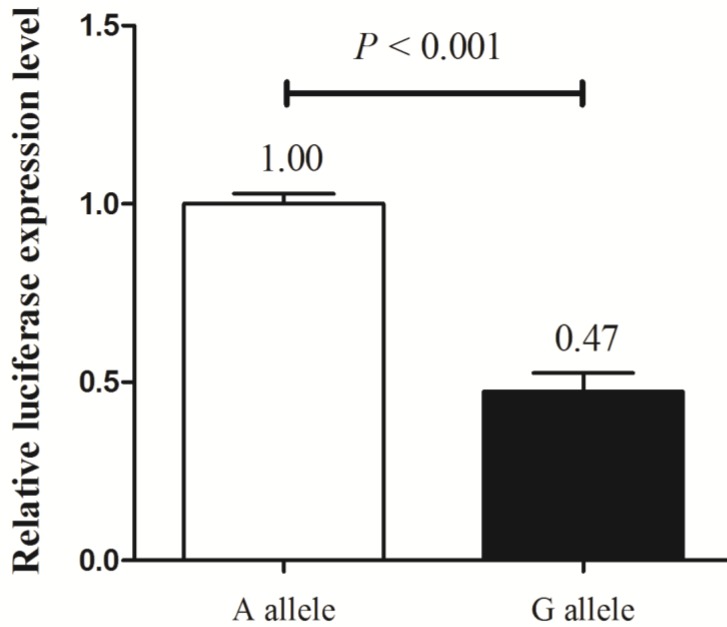

The effects of MALAT1 polymorphism on MALAT1 transcription in functional analysis

Next, we explored the functional effects of different alleles of MALAT1 rs619586 by luciferase assay in TPC-1 cell line. After transfection, cells transfected with plasmid with G allele demonstrated a substantially decreasing trend of luciferase activity compared with those transfected with plasmid containing A allele (P < 0.001, fold change = 2.11, figure 2). Combined with the findings above, these results suggested that the A allele of rs619586 could directly influence MALAT1 expression in PTC.

Figure 2.

The effect of rs619586 on lnc MALAT1 transcriptional activity detected by luciferase assay.

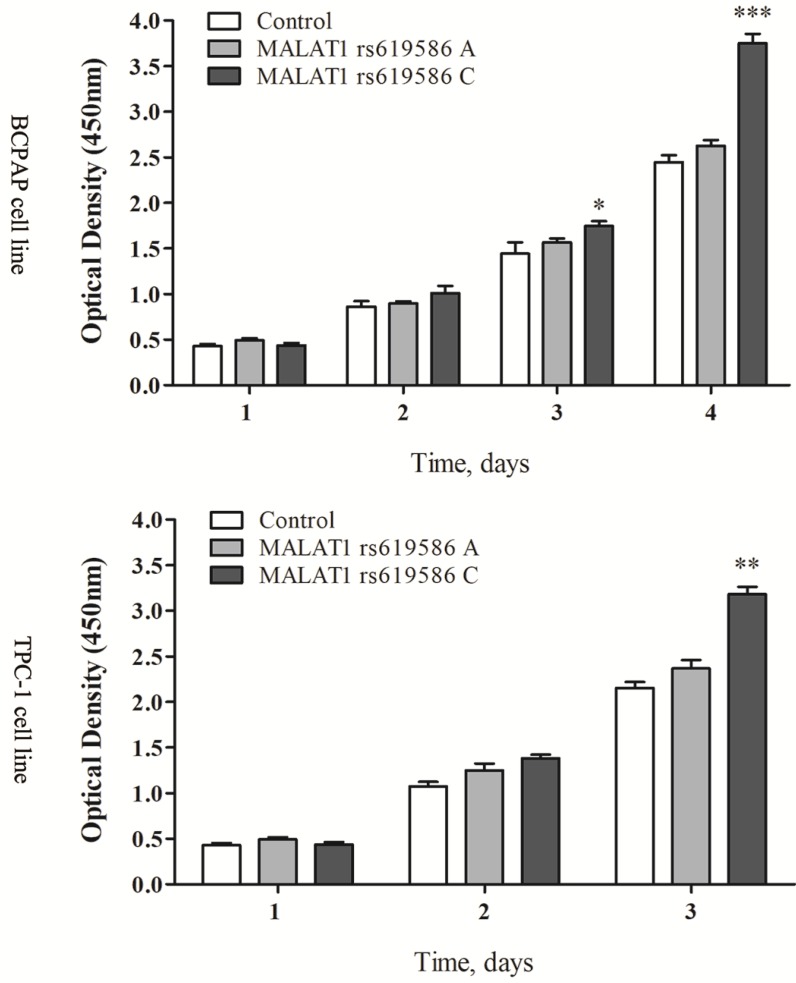

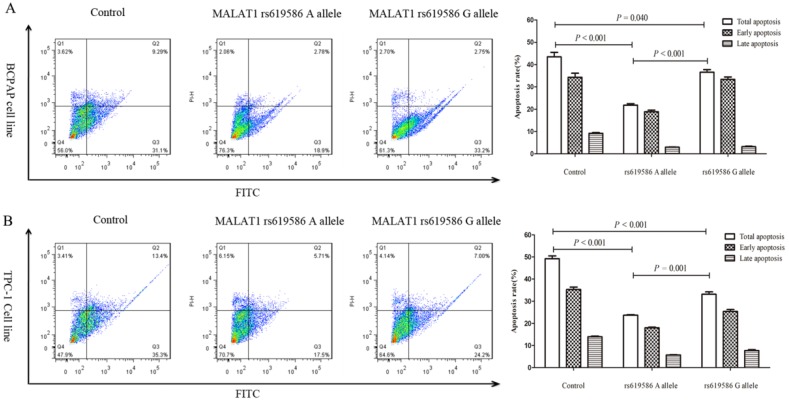

The different phenotypes of thyroid cancer cell line induced by MALAT1 polymorphism

We also examined rs619586's effect on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Proliferation increased significantly in cells transfected with MALAT1 expression plasmid carrying A allele than G allele in the rs619586 site (figure 3), while the apoptosis capacity showed the opposite (figure 4). These findings further indicated SNP rs619586's molecular function and mechanism in papillary thyroid carcinogenesis.

Figure 3.

The lnc MALAT1 rs619586 influence the proliferation of PTC cells.

Figure 4.

The impact of lnc MALAT1 rs619586 on PTC cell apoptosis. (A) the apoptosis of 10μg/ml cisplatin pre-treated BCPAP cell line; (B) the apoptosis of 10μg/ml cisplatin pre-treated TPC-1 cell line.

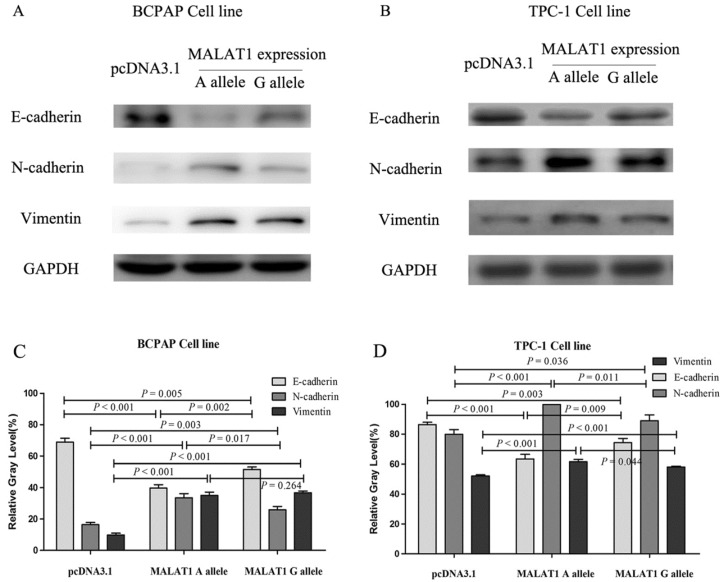

The EMT effects induced by different alleles of MALAT1 rs619586

The EMT-related proteins were tested after transfection of different MALAT1 expression plasmids. The E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin were chosen as the markers of EMT. The E-cadherin of cells transfected with MALAT1 expression plasmid carrying rs619586 A alllele was lower than that carrying G allele in both mRNA level and protein level, while N-cadherin and vimentin displayed diametric trends (figure 5).

Figure 5.

The variations of EMT markers influenced by MALAT1 with different rs619586 polymorphism. (A) the protein levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin in BCPAP cell line; (B) the protein levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin in TPC-1 cell line; (C) the corresponding relative gray assay level of (A); (D) the corresponding relative gray level of (B).

Discussion

In this study, we have systematically investigated the association between MALAT1 polymorphisms and TC (especially PTC) risk in a Chinese population. SNP rs619586 G allele was identified as a potential protective factor to reduce the risk of TC. We also demonstrated that rs619586 could influence cell proliferation and apoptosis, potentially via direct regulation on MALAT1 expression.

Overexpression of MALAT1 (metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) was identified in different types of malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer 21, ovarian cancer 22, prostate cancer 23 and other cancers 24, 25. Aberrant expression of MALAT1 was significantly associated with tumor invasion and metastasis, indicating this lncRNA could be a prognostic marker for cancers 26. In tumorigenesis, however, the categories of MALAT1 have still been less comprehensively investigated and understood, especially in TC. In a previous research, the MALAT1 expression was explored in tumor tissues and adjacent normal thyroid tissues in FTC patients. The average profile of MALAT1 in tumor cells was over 4-fold higher than in the corresponding normal cells 27. Besides, MALAT1 was also up-regulated in MTC patients, with an expression 150 times as much as normal thyroid tissues 28. In addition, our data in PTC patients indicated a high profile of MALAT1 in cancerous tissues. There was approximate 2-fold expression of MALAT1 in 64 PTC patients' cancerous tissues over normal tissues (Figure 1). These results confirmed MALAT1 overexpression in TC patients.

After decades of research on polymorphisms, several functional SNPs have been identified to involve in gene transcription and translation via different mechanisms 29, 30, and these regulations also exist in lncRNA expression 13, 31, 32. Our results also indicated SNP rs619586 triggered the increasing growth and suppressed apoptosis in thyroid cells. These findings demonstrated that the variants of rs619586 could directly induce the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process of cells, an essential mechanism in cellular remodeling during carcinogenesis 33. Considering the promoter activity of different alleles of rs619586 and the corresponding variants of EMT markers, it is reasonable that this SNP trigger the EMT via up-regulating MALAT1 expression. These results were partially in accordance with the role of MALAT1 in EMT 34.

Recently, two independent GWAS researches about PTC in European populations. However, these studies did not list rs619586 in their results. For GWAS study usually remained the SNPs with P < 10-8 as remarkable results, it will lose information about other potential significant SNPs. Therefore, we downloaded the GWAS database of thyroid cancer and evaluated this SNP to seem whether this SNP was significant in European population. Unexpectedly, the SNP rs619586 did not display any significance in these European populations. Then we retrospected the MAF of SNP rs619586, the SNPs distributed differently in European population and in the Chinese population. Therefore, we believed the ethnic difference might lead to this problem.

Nevertheless, there are limitations in this study. One potential pitfall is that this study was based on a population enrolled from the hospital, therefore selection bias could be possible. Although we recruited over 1000 PTC patients and controls, the statistical power could be further improved in future large-scale study; replications of crowd tests in larger population and in population with different ethnicity might be helpful to make our results more convincing. Besides, tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, and dietary preference were potential confounders for PTC but such information was partly missing in our study. In addition, because of the feature of the case-control study, our research could hardly display the final causal relationship effect of MALAT1 in stratified features.

Conclusion

We identify that MALAT1 SNP rs619586 is associated with the risk of PTC in the Chinese population, and this polymorphism could directly reduce MALAT1 expression for the first time. We further demonstrate that SNP rs619586 could influence thyroid cell proliferation and apoptosis, indicating its potential role as a novel susceptibility for the papillary thyroid carcinogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table 1.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81760141), the Guizhou Provincial Project of Science and Technology Foundation (Grant No. 20161122) and the Start-up Funding of Henan University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 13480027).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzaferri EL. An overview of the management of papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 1999;9:421–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns WR, Zeiger MA. Differentiated thyroid cancer. Seminars in oncology. 2010;37:557–66. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirk BW, Feinsod M, Favis R, Kliman RM, Barany F. Single nucleotide polymorphism seeking long term association with complex disease. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:3295–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirooz HJ, Jafari N, Rastegari M, Fathi-Roudsari M, Tasharrofi N, Shokri G. et al. Functional SNP in microRNA-491-5p binding site of MMP9 3'-UTR affects cancer susceptibility. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2018;119:5126–34. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Titeux M, Pendaries V, Tonasso L, Decha A, Bodemer C, Hovnanian A. A frequent functional SNP in the MMP1 promoter is associated with higher disease severity in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Human mutation. 2008;29:267–76. doi: 10.1002/humu.20647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan BM, Robles AI, McClary AC, Haznadar M, Bowman ED, Pine SR. et al. Identification of a functional SNP in the 3'UTR of CXCR2 that is associated with reduced risk of lung cancer. Cancer research. 2015;75:566–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Parry S, Macones G, Sammel MD, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G. et al. A functional SNP in the promoter of the SERPINH1 gene increases risk of preterm premature rupture of membranes in African Americans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:13463–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser S, Go C, Aniss A, Sidhu S, Delbridge L, Learoyd D. et al. BRAF(V600E) Mutation is Associated with Decreased Disease-Free Survival in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. World journal of surgery. 2016;40:1618–24. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3534-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Lee KE, Myong JP, Park JH, Jeon YK, Min HS. et al. BRAF V600E mutation is associated with tumor aggressiveness in papillary thyroid cancer. World journal of surgery. 2012;36:310–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi RL, Qu N, Liao T, Wei WJ, Lu ZW, Ma B. et al. Relationship of body mass index with BRAF (V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid cancer. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37:8383–90. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong J, Tian J, Lou J, Ke J, Li L, Li J. et al. A functional polymorphism in lnc-LAMC2-1:1 confers risk of colorectal cancer by affecting miRNA binding. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:443–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang X, Gao Y, Yu L, Lu Y, Zhou G, Cheng L. et al. Correlations between lncRNA-SOX2OT polymorphism and susceptibility to breast cancer in a Chinese population. Biomarkers in medicine. 2017;11:277–84. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H, Zhang DY, Li X, Yuan XQ, Yang YL, Zhu KW. et al. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 polymorphism predicts a poor prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia in Chinese patients via affecting hematopoietic reconstitution. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2017;58:1948–57. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1266626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A. et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT. et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316:1484–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt LH, Spieker T, Koschmieder S, Schaffers S, Humberg J, Jungen D. et al. The long noncoding MALAT-1 RNA indicates a poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer and induces migration and tumor growth. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2011;6:1984–92. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307eac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuo Y, Zeng Q, Zhang P, Li G, Xie Q, Cheng Y. Functional polymorphism of lncRNA MALAT1 contributes to pulmonary arterial hypertension susceptibility in Chinese people. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2017;55:38–46. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong WJ, Peng JB, Yin JY, Li XP, Zheng W, Xiao L. et al. Association between well-characterized lung cancer lncRNA polymorphisms and platinum-based chemotherapy toxicity in Chinese patients with lung cancer. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2017;38:581–90. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen J, Gao Q, Wang N, Zhang W, Cao K, Zhang Q. et al. Association of microRNA-related gene XPO5 rs11077 polymorphism with susceptibility to thyroid cancer. Medicine. 2017;96:e6351. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Boing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM. et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:8031–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Xu X, Lv H, Wen Q, Li J, Tan L. et al. The Long Noncoding RNA MALAT-1 Is Highly Expressed in Ovarian Cancer and Induces Cell Growth and Migration. PloS one. 2016;11:e0155250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren S, Liu Y, Xu W, Sun Y, Lu J, Wang F. et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 is a new potential therapeutic target for castration resistant prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2013;190:2278–87. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiao F, Hu H, Yuan C, Wang L, Jiang W, Jin Z. et al. Elevated expression level of long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 facilitates cell growth, migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer. Oncology reports. 2014;32:2485–92. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian Y, Zhang X, Hao Y, Fang Z, He Y. Potential roles of abnormally expressed long noncoding RNA UCA1 and Malat-1 in metastasis of melanoma. Melanoma research. 2014;24:335–41. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Xue D, Li Y, Pan X, Zhang X, Kuang B. et al. The Long Noncoding RNA MALAT-1 is A Novel Biomarker in Various Cancers: A Meta-analysis Based on the GEO Database and Literature. Journal of Cancer. 2016;7:991–1001. doi: 10.7150/jca.14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang JK, Ma L, Song WH, Lu BY, Huang YB, Dong HM. et al. MALAT1 promotes the proliferation and invasion of thyroid cancer cells via regulating the expression of IQGAP1. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2016;83:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu YH, Hardin H, Schneider DF, Chen H, Lloyd RV. MicroRNA-21 and long non-coding RNA MALAT1 are overexpressed markers in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2017;103:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu M, Gao Y, Yu T, Wang J, Cheng L, Cheng L. et al. Functional promoter rs2295080 T>G variant in MTOR gene is associated with risk of colorectal cancer in a Chinese population. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2015;70:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Q, Ju X, Li P, Meng X, Shao P, Cai H. et al. A functional variant in the MTOR promoter modulates its expression and is associated with renal cell cancer risk. PloS one. 2012;7:e50302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du M, Wang W, Jin H, Wang Q, Ge Y, Lu J. et al. The association analysis of lncRNA HOTAIR genetic variants and gastric cancer risk in a Chinese population. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31255–62. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu H, Liu Q, Li J, Wang X, Wang Y, Yuan Z. et al. Analysis of the association of HOTAIR single nucleotide polymorphism (rs920778) and risk of cervical cancer. APMIS: acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2016;124:567–73. doi: 10.1111/apm.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suarez-Carmona M, Lesage J, Cataldo D, Gilles C. EMT and inflammation: inseparable actors of cancer progression. Molecular oncology. 2017;11:805–23. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang J, Liang L, Ouyang K, Li Z, Yi X. MALAT1 induces tongue cancer cells' EMT and inhibits apoptosis through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Journal of oral pathology & medicine: official publication of the International Association of Oral Pathologists and the American Academy of Oral Pathology. 2017;46:98–105. doi: 10.1111/jop.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1.