Abstract

Introduction:

Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a common gynecological condition managed syndromically in most developing countries. In Zimbabwe, women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge are treated with empirical regimens that commonly cover both sexually transmitted infections (STI) and reproductive tract infections, typically including a combination of an intramuscular injection of kanamycin, and oral doxycycline and metronidazole regimens. This study was conducted to determine the current etiology of symptomatic vaginal discharge and assess adequacy of current syndromic management guidelines.

Methods:

We enrolled 200 women with symptomatic vaginal discharge presenting at 6 STI clinics in Zimbabwe. Microscopy was used to detect bacterial vaginosis and yeast infection. Nucleic acid amplifications tests were used to detect Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Mycoplasma genitalium. In addition, serologic testing was performed to detect HIV infection.

Results:

Of the 200 women, 146 (73%) had an etiology detected, including bacterial vaginosis (24.7%); N. gonorrhoeae (24.0%); yeast infection (20.7%); T. vaginalis (19.0%); C. trachomatis (14.0%) and M. genitalium (7.0%). Among women with STIs (N=90), 62 (68.9%) had a single infection, 18 (20.0%) had a dual infection and 10 (11.1%) had three infections.

Of 158 women who consented to HIV testing, 64 (40.5%) were HIV infected.

The syndromic management regimen covered 115 (57.5%) of the women in the sample who had gonorrhea, chlamydia, M. genitalium, or bacterial vaginosis, while 85 (42.5%) of women were treated without such diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Among women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge, bacterial vaginosis was the most common etiology and gonorrhea was the most frequently detected STI. The current syndromic management algorithm is suboptimal for coverage of women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge; addition of point of care testing could compliment the effectiveness of the syndromic approach.

Keywords: Vaginal Discharge, STI, Etiology, Syndromic Management

Brief Summary:

Among women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge at primary health clinics in Zimbabwe, bacterial vaginosis (24.7%) and N. gonorrhoeae infection (24%) were the most common etiologies.

Introduction

Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a common gynecological condition among women of child bearing age accounting for an estimate of 5–10 million clinic visits per year throughout the world.1 Vaginal discharge may be a normal occurrence in pregnancy, menstruation or use of estrogen containing hormonal contraception.2–4 Abnormal vaginal discharge occurs commonly among women with bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, trichomoniasis, chlamydia and gonorrhea.2,5 The presence of abnormal vaginal discharge may also be associated with multiple adverse reproductive tract outcomes that include pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and a greater than 2–3 fold increased risk of HIV acquisition.6–10 In most clinical settings, the management of vaginal discharge is mainly syndrome driven and empirical due to limited point-of-care diagnostic tools to differentiate causative etiologies.4,7,10–12 These empirical regimens commonly cover a spectrum of pathogens that are identifiable causes of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and reproductive tract infections (RTIs). RTIs are typically endogenous infections caused by overgrowth of organisms present in the genital tract.

In 2015, a total of 252,406 adult STI cases were reported syndromically to the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care of which 79,371 (31.4%) were women with vaginal discharge (unpublished data). The 2013 Zimbabwe STI treatment guidelines recommend that all women presenting with vaginal discharge should receive a course of oral metronidazole tablets (400mg or 500mg orally, 3 times a day for 7 days OR 2g orally, single dose) as empirical treatment for bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. Additional anti-fungal treatment using miconazole (200mg vaginal pessaries once at night for 3 days) or clotrimazole vaginal tablet (100mg at night for 7 days) is only indicated when clinical manifestations of candidiasis are apparent. Women presenting with muco-purulent vaginal discharge are recommended a regimen that includes kanamycin (2 grams intramuscularly, single dose) or ceftriaxone (250mg intramuscularly, single dose) in addition to doxycycline (100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days) as empirical treatment for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.13

Syndromic management of symptomatic vaginal discharge is based on clinical signs and symptoms with potential risk of overtreatment and development of antimicrobial resistance in the absence of identified etiological organism.1,4,7,10 To monitor epidemiological shifts in the etiology of vaginal discharge, it is essential to conduct periodic surveys to provide evidence based treatment strategies to policy makers.12

The purpose of this study was to establish the etiology of vaginal discharge syndrome among women presenting with symptoms of vaginal discharge in Zimbabwean clinics. The results will be used to assess the continued applicability of existing syndromic treatment guidelines in Zimbabwe.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This is a sub-study of the Zimbabwe STI Etiology study conducted in 2014 – 2015 whose main objective was to establish the etiology of STI syndromes in Zimbabwe, including male urethral discharge syndrome, male and female genital ulcer disease, and vaginal discharge syndrome. Results of the urethral discharge and genital ulcer disease sub-studies have been published in this journal previously14,15 and a general description or the study’s methodology and study population is available online.16 This manuscript reports on female study participants presenting with vaginal discharge.

The full study protocol including consent forms and questionnaires are available online.17 Six regionally and ethnically diverse STI clinics were selected. Two clinics were selected from Harare (Mbare and Budiriro); two from Bulawayo (Nkulumane and Khami Road); one from border town Beitbridge (Dulibadzimu) and one from a rural community (Gutu Hospital). More details on clinic selection can be found in the study protocol.17

Through convenience sampling, trained nurses recruited 200 consecutively eligible women aged 18–53 years presenting with vaginal discharge at the study clinics. Based on statistical considerations as well as limited resources available to the study, we felt that a sample size of 200 would strike an acceptable balance between available study resources and the need for precision.17

Sexually active women presenting with subjective complaints of abnormal vaginal discharge were included in the study. Patients were ineligible if they did not speak Shona, English or Ndebele (the 3 major languages spoken in Zimbabwe); if they were unable to provide consent; or if they had received treatment for STIs in the previous 4 weeks. Study enrolment was conducted from June 2014 to April 2015.

Study procedures

Patients who met the eligibility criteria underwent a consenting process and were asked to sign an informed consent form covering all study procedures. The study nurse then completed a paper copy questionnaire that included demographic information, sexual history, description of symptoms, history of STI/HIV and current use of medications. Each consenting patient underwent genital examination including speculum insertion and received vaginal discharge pH testing by a strip method. Four vaginal swabs were collected and one swab was used to make a smear for Gram stain. A blood sample was taken for HIV testing, among those who consented to this test. All patients were treated for STIs according to the 2013 Zimbabwe STI treatment guidelines.13 Paper data were reviewed and transcribed into a computer based data system on hand held devices. Data were uploaded at least daily from study sites to an online secure central database.

Laboratory procedures

All specimens were kept refrigerated (2 – 8 °C) and shipped in a cooler box with cooling packs the same day or overnight to the receiving laboratory at Wilkins Hospital in Harare where the specimens were kept refrigerated until further processing. Vaginal swabs were stored in a freezer at −70°C and batched for shipment. One swab was shipped to the STI reference laboratory at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) in Johannesburg, South Africa. At the NICD laboratory Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Mycoplasma genitalium were tested using an in-house developed multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) developed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, United States).5 The other two vaginal swabs were shipped to two local laboratories to perform additional testing for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) using Becton Dickinson ProbeTec (BD Molecular Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at the University of Zimabwe College of Health Science - Clinical Trial Unit Central Laboratory in the Obsterics and Gynaecology department of the University of Zimbabwe and using GeneXpert (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at the Flowcytometry laboratory in Harare. For the purposes of comparisons with T. vaginalis and M. genitalium in this study, we only included results from the M-PCR. However, concordance between M-PCR with Probetec and GeneXpert (i.e., the 3 tests were either all positive or all negative) was >95% for both gonorrhea and chlamydia. A comparative study has been presented elsewhere.18

HIV testing was performed at the study laboratory at Wilkins Hospital in Harare using the standard rapid testing algorithm used in Zimbabwe.∗ Syphilis testing using treponemal and non-treponemal assays were also conducted, however reporting on results fell outside the scope of this manuscript and will be presented elsewhere. Gram staining was also conducted in the laboratory at Wilkins Hospital to diagnose candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis. Candidiasis was defined as the presence of budding yeast of pseudo-hyphae and bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed using the Nugent criteria19 ; a score of 0 – 3 was considered normal, a score of 4 – 6 was considered intermediate and a score of 7 – 10 was classified as bacterial vaginosis. While Gram stain is an insensitive test for gonorrhea, the presence of intracellular Gram-negative diplococci organisms on Gram stain was recorded. All testing was done using standard operating procedures. More detail on laboratory procedures can be found in the online supplement.17

Data analysis

Data on participant demographics and sexual health and STI history were analyzed using SAS software (Cary, NC, USA). Tests for statistical significance testing included Chi-Square and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s T-test for continuous variables.

Since we assumed the possibility of variations and clustering by clinic, we did not attempt to generalize the relative prevalence of pathogens and conditions associated with vaginal discharge in our study and hence do not present 95% confidence intervals.

For purposes of the analysis in this manuscript, clinics were combined into 3 regions: Harare, Bulawayo, and Beitbridge/Gutu.

Ethical considerations

The protocol, consent forms and questionnaires were reviewed and approved by the University of Zimbabwe Joint Research and Ethics Committee of Parirenyatwa Central Hospital, the Zimbabwe Medical Research Council and the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Results

Demographics and Risk Factors

Selected demographic characteristics and risk factors among women presenting with vaginal discharge are presented in Table 1. Of the 200 enrolled women, 69 (34.5%) were from Harare including 19 pregnant women, 69 (34.5%) were from Bulawayo including 1 pregnant woman, 59 (29.5%) were from Beitbridge and 3 (1.5%) from Gutu. Women recruited were predominantly Shona (63.5%), however, as expected women recruited in Bulawayo were significantly more Ndebele, given that Ndebele is the predominant population in the region. The mean and median ages were 27.6 years and 26 years respectively. Sixty-two percent of women were married and only 12.5% were employed. Previous history of STI was reported among 27.9% of the patients. In the preceding 3 months, 7.5% of women reported multiple sex partners while 8.5% reported sex work. Absence of condom use at last sex with main and casual partner was reported by 71.6% and 66.9% of women respectively. Participants from Beitbridge or Gutu were significantly more likely to report sex work and having more than one partner in the previous 3 months.

Table 1:

Demographics and Risk Factors Among Women Presenting with Vaginal Discharge

| All clinics | % | Harare | % | Bulawayo | % | Beitbridge/Gutu | % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluable Participants | 200 | 69 | 34.5 | 69 | 34.5 | 62 | 31.0 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Shona | 127 | 63.5 | 66 | 95.7 | 14 | 20.3 | 47 | 75.8 | <0.0001 |

| Ndebele | 57 | 28.5 | 2 | 2.9 | 49 | 71.0 | 6 | 9.7 | |

| Other | 16 | 8.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 6 | 8.7 | 9 | 14.5 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| Mean | 27.6 | - | 27.4 | - | 28.1 | - | 27.3 | - | NS |

| Median | 26.0 | - | 26.0 | - | 25.0 | - | 26.0 | - | |

| Age Category (Years) | |||||||||

| 15–19 | 17 | 8.5.5 | 4 | 5.8 | 7 25 |

10.2 | 6 | 9.7 | NS |

| 20–24 | 64 | 32.0 | 23 | 33.3 | 25 | 36.2 | 16 | 25.8 | |

| 25–29 | 49 | 24.5 | 18 | 26.1 | 11 | 15.9 | 20 | 32.3 | |

| 30–34 | 36 | 18.0 | 13 | 18.8 | 13 | 18.8 | 10 | 16.1 | |

| 35–39 | 20 | 10.0 | 8 | 11.6 | 5 | 7.3 | 7 | 11.3 | |

| ≥40 | 14 | 7.0 | 3 | 4.4 | 8 | 11.6 | 3 | 4.8 | |

| More than 1 partner in previous 3 months | |||||||||

| No | 185 | 92.5 | 67 | 97.1 | 67 | 97.1 | 51 | 82.3 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 15 | 7.5 | 2 | 2.9 | 2 | 2.9 | 11 | 17.7 | |

| Sex work in previous 3 months | |||||||||

| No | 183 | 91.5 | 64 | 92.8 | 67 | 97.1 | 52 | 83.9 | <0.05 |

| Yes | 17 | 8.5 | 5 | 7.2 | 2 | 2.9 | 10 | 16.1 | |

| Condom use at last sex with main partner* | |||||||||

| No | 141 | 71.6 | 54 | 78.3 | 48 | 72.7 | 39 | 62.9 | NS |

| Yes | 56 | 28.4 | 15 | 21.7 | 18 | 27.3 | 23 | 37.1 | |

| Missing | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |||||

| Condom use at last sex with casual partner* | |||||||||

| No | 107 | 66.9 | 29 | 80.6 | 42 | 67.7 | 36 | 58.1 | NS |

| Yes | 53 | 33.1 | 7 | 19.4 | 20 | 32.3 | 26 | 41.9 | |

| Missing | 40 | 33 | 7 | 0 | |||||

| Perceived HIV Status | |||||||||

| Negative | 55 | 27.5 | 17 | 24.6 | 24 | 34.8 | 14 | 22.6 | NS |

| Positive | 64 | 32.0 | 16 | 23.2 | 22 | 31.9 | 26 | 41.9 | |

| Unknown | 81 | 40.5 | 36 | 52.2 | 23 | 33.3 | 22 | 35.5 | |

| STI History | |||||||||

| No | 142 | 72.1 | 45 | 67.2 | 49 | 72.1 | 48 | 77.4 | NS |

| Yes | 55 | 27.9 | 22 | 32.8 | 19 | 27.9 | 14 | 22.6 | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 124 | 62.0 | 57 | 82.6 | 37 | 53.6 | 30 | 48.4 | <0.0001 |

| Unmarried | 76 | 38.0 | 12 | 17.4 | 32 | 46.4 | 32 | 51.6 | |

| Employed | |||||||||

| Yes | 25 | 12.5 | 8 | 11.6 | 10 | 14.5 | 7 | 11.3 | NS |

| No | 175 | 87.5 | 61 | 88.4 | 59 | 85.5 | 55 | 88.7 | |

| Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 20 | 10 | 19 | 27.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001 |

| No | 180 | 90 | 50 | 72.5 | 68 | 98.5 | 62 | 100 |

Percentages and Chi Square/T-Test analyses limited to non-missing data

Gram Stain Results

Gram stain results were available for 198 women. Nugent scores were as follows: 0–3: 75 (37.9%); 4–6: 70 (35.3%) and 7–10: 53 (26.8%). Forty-one (20.7%) women had Gram stain evidence of yeast infections and 18 (9.1%) women had evidence of gonorrhea. When excluding women with a Gram stain diagnosis of yeast infection or gonorrhea, 49 women (24.7%) were diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis based on a Nugent score of 7 or higher and 90 (45.5%) had a normal Gram stain.

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (M-PCR) Results

M-PCR results were available for all 200 women and pathogens were detected in 90 women (45.0%), including N. gonorrhoeae (48/200, 24.0%), T. vaginalis (38/200, 19.0%), C. trachomatis (28/200, 14.0%) and M. genitalium (14/200, 7.0%). There were no significant variations in prevalence of STI etiologies across recruitment sites (Table 2). All 18 women with gonorrhea identified on Gram stain tested positive for N. gonorrhoeae by M-PCR.

Table 2:

Prevalence of STI Etiologies by Recruitment Site and Frequency of Co-Infections

| All clinics | Harare | Bulawayo | Beitbridge/ Gutu | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 200 | 69 | 69 | 62 | |||||

| Pathogen | |||||||||

| N. gonorrhoeae | 48 | 24.0 | 13 | 18.8 | 17 | 24.6 | 18 | 29.0 | NS |

| C. trachomatis | 28 | 14.0 | 6 | 8.7 | 11 | 15.9 | 11 | 17.7 | NS |

| T. vaginalis | 38 | 19.0 | 10 | 14.5 | 17 | 24.6 | 11 | 17.7 | NS |

| M. genitalium | 14 | 7.0 | 5 | 7.2 | 4 | 5.8 | 5 | 8.1 | NS |

| Any Infection | 90 | 45.0 | 26 | 37.7 | 31 | 44.9 | 33 | 53.2 | NS |

| No Infection | 110 | 55.0 | 43 | 62.3 | 38 | 55.1 | 29 | 46.8 | NS |

Key: NG - N. gonorrhoeae; TV - T. vaginalis; CT - C. trachomatis; MG - M. genitalium

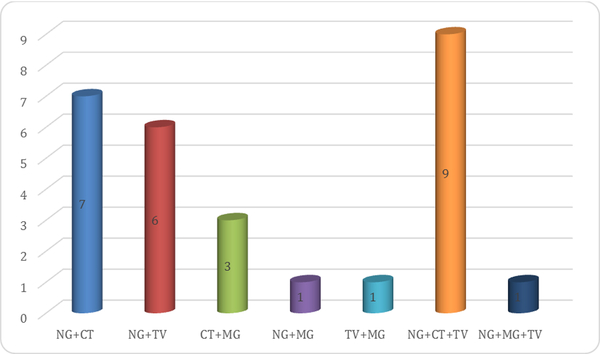

Of the 90 women who had pathogens identified, 62 (68.9%) had a single infection, 18 (20.0%) had a dual infection and 10 (11.1%) had three infections (Figure 1). Most co-infections were a combination of gonorrhea with chlamydia and trichomonas (n=9); gonorrhea and chlamydia (n=7) and gonorrhea and trichomonas (n=6). In addition, 24/49 (49%) of women with bacterial vaginosis but only 10/41 (24.4%) of women with candidiasis had at least one STI (p<0.05).

Figure 1: Frequency of co-infections between various pathogens among women.

Key: NG - N. gonorrhoeae; TV - T. vaginalis; CT - C. trachomatis; MG - M. genitalium

When analyzing the etiology of vaginal discharge in our study by each component of the typical syndromic management for this condition (i.e., a combination of kanamycin, doxycycline and metronidazole), the kanamycin component covered 48 (24.0%) women in the sample who had gonorrhea, the doxycycline component covered 60 (30.0%) women who either had gonorrhea or chlamydia, and the metronidazole component covered 77 (38.5) of women who either had bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis. Combined, the syndromic management regimen covered 115 (57.5%) of the women in the sample who had gonorrhea, chlamydia, M. genitalium, trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis, while 85 (42.5%) of women were treated without such diagnosis. The treatment components in the current algorithm13 did not include a macrolide; therefore 14/200 (7%) of women with Mycoplasma genitalium may have received sub-optimal treatment.

PH

PH assessment was available for 191/200 (95.5%) of women. The mean PH was 5.2 (median 5.3, interquartile range 0.5). Using the median PH value, 82 women (42.9%) had a PH lower than 5.3 and 109 (57.1%) had a PH of 5.3 or higher. Only 8 women in the study had a PH of ≤ 4.5. Associations of PH at the 5.3 cut-off with etiologic conditions linked to vaginal discharge is presented in Table 3. Higher PH was statistically significantly associated with a diagnosis of BV and gonococcal infection and marginally associated with chlamydial infection. Lower PH was associated with yeast infection or normal findings. There was no association with trichomonas infection. Performance of the PH test (at the 5.3 cut-off) to predict any condition covered under the syndromic guidelines (i.e., BV or infection with N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, T. vaginalis, or M. genitalium) were as follows: sensitivity: 73/108 (67.6%); specificity: 47/83 (56.6%); predictive value of a high PH: 73/109 (67.0%); predictive value of low PH: 47/82 (57.3%).

Table 3.

PH Test Results* Among Women With Vaginal Discharge Syndrome

| Test Performance** | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Prevalence (N/%) | OR | P | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV+ | PPV− | ||

| Low PH | High PH | ||||||||

| Gram Stain | 191 | 82 | 109 | ||||||

| BV | 45 | 12 (14.6) | 33 (30.3) | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | <0.05 | 73.3 | 47.3 | 30.3 | 85.4 |

| Yeast | 39 | 23 (28.0) | 16 (14.7) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | <0.05 | 59.0 | 61.2 | 28.0 | 85.3 |

| Normal | 88 | 43 (52.4) | 45 (41.3) | 0.6 (0.4–1.1) | NS | 48.9 | 62.1 | 52.4 | 58.7 |

| M-PCR | 191 | 82 | 109 | ||||||

| N. gonorrhoeae | 45 | 13 (16.0) | 32 (29.4) | 2.2 (1.1–4.5) | <0.05 | 71.1 | 47.3 | 29.4 | 84.0 |

| C. trachomatis | 27 | 7 (3.6) | 20 (18.3) | 2.4 (0.9–6.0) | 0.06 | 74.1 | 45.7 | 18.3 | 91.4 |

| T. vaginalis | 36 | 14 (17.1) | 22 (20.2) | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | NS | 61.1 | 43.9 | 20.2 | 82.9 |

| M. genitalium | 13 | 3 (3.7) | 10 (9.2) | 2.7 (0.9–9.9) | NS | 76.9 | 44.4 | 9.2 | 96.3 |

| Any infection | 86 | 29 (35.4) | 57 (52.3) | 2.0 (1.1–3.6) | <0.05 | 66.3 | 50.5 | 52.3 | 64.6 |

| Any infection or BV | 108 | 35 (42.7) | 73 (67.0) | 2.7 (1.5–4.9) | <0.01 | 67.6 | 56.6 | 67.0 | 57.3 |

Low PH: ≤ 5.2 ; High PH: >5.2

Low vs. high PH for all infections/conditions, except yeast infection and normal Gram stain

HIV Infection

Of the 158 women who consented to HIV testing, 64 (40.5%) were HIV infected. The burden of STIs was higher amongst women with HIV infection compared to HIV uninfected women (54.7% versus 37.2%, p<0.05). Table 4 shows association of HIV with STIs and RTIs. Women with T. vaginalis infection were more likely to be HIV infected than women without T. vaginalis infection (59.4% versus 35.7%, p < 0.05). Women with gonorrhea were also more likely to be HIV infected compared to women without gonorrhea (54.1% versus 36.4%, p = 0.05). Although not significantly different, women with chlamydia infection were less likely to be HIV infected compared to women without chlamydia infection (22.7% versus 43.4%, p=0.06), however this association disappeared when controlling for age (data not shown).

Table 4:

Association of HIV with Sexually Transmitted Infections and Reproductive Tract Infections

| Number tested | No. HIV Infected | % | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 158 | 64 | ||

| N. gonorrhoeae | ||||

| Yes | 37 | 20 | 54.1 | P=0.05 |

| No | 121 | 44 | 36.4 | |

| C. trachomatis | ||||

| Yes | 22 | 5 | 22.7 | P= 0.06 |

| No | 136 | 59 | 43.4 | |

| M. genitalium | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 7 | 58.3 | NS |

| No | 146 | 57 | 39 | |

| T. vaginalis | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 19 | 59.4 | P<0.05 |

| No | 126 | 45 | 35.7 | |

| Any infection | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 35 | 50 | P<0.05 |

| No | 88 | 29 | 32.9 | |

| Bacterial vaginosis* | ||||

| Yes | 39 | 15 | 38.5 | NS |

| No | 74 | 29 | 39.2 | |

| Yeast infection* | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 12 | 38.7 | NS |

| No | 74 | 29 | 39.2 |

Compared to normal Gram Stain

There was no association between HIV infection and diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis or yeast infection.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this sub-study was to establish the etiology of vaginal discharge syndrome among women presenting to selected Zimbabwe STI clinics, in order to assess the adequacy of current treatment guidelines against the prevalent causes of vaginal discharge.

Bacterial vaginosis (24.7%) was the most prevalent cause identified among women presenting with vaginal discharge syndrome. The predominance of bacterial vaginosis as a common cause of vaginal discharge syndrome is an observation that has been reported in several other studies among women with reproductive tract infections.4–7,10 Detection of STIs by M-PCR was most common for N. gonorrhoeae (24.0%), T. vaginalis (19.0%) and C. trachomatis (14.0%). The observed higher burden of N. gonorrhoeae compared to C. trachomatis in our study is in contrast to previous studies amongst asymptomatic women conducted in Zimbabwe20,21 and in sub -Saharan Africa which revealed a higher burden of C. trachomatis than N. gonorrhoeae.22 This could be a manifestation resulting from the more symptomatic nature of gonorrhea than chlamydia, such that women infected with N. gonorrhoeae are more likely to present to a health care facility.23

The presence of multiple concurrent infections was most commonly identified among women infected with N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and T. vaginalis, a manifestation that typically presents with muco-purulent vaginal discharge. This study also reveals presence of M. genitalium (7.0%). This organism has been reported as a cause of STI in several countries and an association with HIV has been reported.24–26 Replacing doxycycline with azithromycin in the syndromic treatment algorithm may increase coverage for M. genitalium while still providing adequate coverage for chlamydia (azithromycin is currently listed as an alternative regimen in the Zimbabwe STI treatment guidelines13). However a 23S rRNA mutation in the M. genitalium ribosome has resulted in rapidly increasing macrolide resistance world-wide, especially in countries that have replaced doxycycline with azithromycin in their STI treatment guidelines, leaving a conundrum for appropriate syndromic management and providing another rationale for etiologic testing.27

A significant number of women presenting with vaginal discharge syndrome were HIV infected (40.5%) compared to HIV prevalence of 15.6% in the general population.28 The burden of STIs was higher amongst HIV-infected women (54.7% versus 37.2%, p<0.05). Trichomoniasis was significantly associated with HIV infection, an observation that has been reported in previous studies.29 These data support a recommendation that the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care should consider offering HIV testing and linkage to care for all women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge. In addition to prompt treatment of STI, partner management for women diagnosed with STI is also crucial to prevent re-infection and on-going transmission.12,30,31

With regards to the adequacy of syndromic management for vaginal discharge syndrome, our study found that 57.5% of women had a pathogen covered by a combination treatment of kanamycin, doxycycline, and metronidazole. However, the kanamycin component over-treated 76% of women who did not have gonorrhea; the doxycycline component over-treated 70% of women who did not have gonorrhea or chlamydia and the metronidazole component over-treated 61.5% of women who did not have bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis. Moreover, treatment for M. genitalium may have been sub-optimal. Our results are in agreement with several studies that have observed a relatively low positive predictive value for the detection of STI when using the vaginal discharge syndrome algorithm5,10,11,30 with potential harm for over treatment, anti-microbial resistance and stigmatization. To avoid the burden of over treatment, there is need for diagnostic capacity at the clinics thus affordable point of care testing32 should be considered for STI screening among women presenting with symptomatic vaginal discharge, including basic microscopy to differentiate BV, trichomoniasis, and yeast infections. Also, point of care testing using nucleic acid amplification technology that is increasingly becoming available for tuberculosis/rifampin resistance testing in developing countries, can easily be utilized for chlamydia and gonorrhea testing on the same platform.

Vaginal PH testing is a simple and cheap test that could be used in the diagnostic differentiation of the vaginal discharge syndrome at the point on of care. Indeed, we found statistically significant associations between a PH ≥ 5.3 and BV or infection with N. gonorrhoeae. However, for practical purposes, the diagnostic differentiation proved to be inadequate: while the positive predictive value was quite high (67%) for women with a high PH who had BV or STI, the negative predictive value was low (i.e., 42.7% of women with a low PH still had BV or STI).

Given the high burden of STIs amongst HIV-infected women and the high level of concurrent STIs, there is a high risk of ongoing HIV transmission in this community. In addition to capacitating clinics with STI point-of-care testing, the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care should consider expanding programs that promote HIV risk reduction. These include condom use promotion and antiretroviral treatment (ART) counseling. Adherence to ART reduces viral load thereby reducing the chances of HIV transmission to sexual partners33. In addition, partners should be offered HIV testing; HIV negative partners should be encouraged to take up pre-exposure prophylaxis to reduce HIV infection34 and HIV positive partners should be encouraged to initiate ART as per WHO guidelines.35

Our study should be understood in light of some limitations. First, for the diagnosis of yeast infection and bacterial vaginosis, the study relied on Gram stain testing; on-site wet mount testing was not conducted. This could have resulted in an under-estimation of both conditions. Moreover, 35% of women had intermediate (4–6) Nugent scores and in one study 32% of women with intermediate scores progressed to bacterial vaginosis , whereas 30% reverted to normal flora.36 Second, this study did not determine antibiotic susceptibility to confirm the effectiveness of the empirical regimens as recommended by the current local guidelines particularly for N. gonorrhoeae.13 However, a recent study conducted in Zimbabwe showed high levels of N. gonorrhoeae susceptibility to kanamycin and ceftriaxone20 and additional studies are ongoing. Third, this study only enrolled symptomatic women that could have resulted in a bias towards a high prevalence of STIs and these results can therefore not be generalized to asymptomatic women; thus requiring additional studies amongst the latter population.

In view of the 42.5% of women with symptomatic vaginal discharge who were over-treated using the current algorithm, we recommend a review of the Zimbabwean STI treatment algorithm with a focus on point of care testing. Point of care testing, especially the use of nucleic acid amplification testing devices that are becoming increasingly available, would also allow for testing of asymptomatic women. Because STIs among women, including gonorrhea and chlamydia infections are often asymptomatic, such an approach would have a greater impact on STI control than the current approach depending on syndromic management.

Acknowledgements:

ZiCHIRe Study Team:

-Luanne Rodgers, Laboratory Scientist

-Vitalis Kupara, State Registered Nurse (SRN)

-Mebbina Muswera, State Registered Nurse and State Registered Midwife(SRN, SRM)

-Sarah Vundhla, State Registered Nurse and State Registered Midwife(SRN, SRM)

-Shirley Tshimanga, State Registered Nurse and State Registered Midwife(SRN, SRM)

This study could not have been conducted without the gracious support and collaboration of the staff and patients of the following clinics:

Harare: Mbare and Budiriro clinics

Bulawayo: Nkulumane and Khami Road Clinics

Beitbridge: Dulibadzimu Clinic

Gutu: Gutu Rural Hospital

The Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study was supported by funds from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through a cooperative agreement between the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the University of Zimbabwe Department of Community Medicine SEAM Project under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number IU2GGH000315–01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HIV testing in Zimbabwe follows a standard algorithm of the following HIV rapid tests: 1) initial test by First Response HIV 1–2.O (Premier Medical Corporation, Daman, India); 2) confirmatory test by Alere Determine HIV 1/2 (Alere, Waltham MS, USA) if the initial test result is positive, and 3) INSTI HIV1/HIV2 (Biolytical, Richmond BC, Canada) as a tiebreaker if the initial and confirmatory tests are discrepant.

References

- 1.Rekha S, Jyothi S. Comparison of visual, clinical and microbiological diagnosis of symptomatic vaginal discharge in the reproductive age group. Int J Pharm Biomed Res. 2010;1(4):144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell H Vaginal discharge--causes, diagnosis, and treatment. BMJ. 2004;328(7451):1306–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.da Fonseca TM, Cesar JA, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Schmidt EB. Pathological Vaginal Discharge among Pregnant Women: Pattern of Occurrence and Association in a Population-Based Survey. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:590416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan SA, Amir F, Altaf S, Tanveer R. Evaluation of common organisms causing vaginal discharge. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21(2):90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhlongo S, Magooa P, Müller EE, et al. Etiology and STI/HIV coinfections among patients with urethral and vaginal discharge syndromes in South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(9):566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masand DL, Patel J, Gupta S. Utility of microbiological profile of symptomatic vaginal discharge in rural women of reproductive age group. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(3):QC04–07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickering JM, Whitworth JA, Hughes P, et al. Aetiology of sexually transmitted infections and response to syndromic treatment in southwest Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):488–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karou SD, Djigma F, Sagna T, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of abnormal vaginal discharges microorganisms in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(4):294–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mlisana K, Naicker N, Werner L, et al. Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a poor predictor of sexually transmitted infections and genital tract inflammation in high-risk women in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ray K, Muralidhar S, Bala M, et al. Comparative study of syndromic and etiological diagnosis of reproductive tract infections/sexually transmitted infections in women in Delhi. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(6):e352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42782/1/9241546263_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 13.Ministry of Health and Child Care - AIDS and TB Unit Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Reproductive Tract Infections in Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe: Ministry of Health and Child Care;2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rietmeijer C, Mungati M, Machiha A, et al. The etiology of urethral discharge in Zimbabwe - Results from the Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2017;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mungati M, Machiha A, Mugurungi O, et al. The etiology of genital ulcer disease and co-infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in Zimbabwe - Results from the Zimbabwe STI Etiology Study Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2017;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rietmeijer C, Mungati M, Machiha A, et al. The Zimbabwe STI etiology study: design, methods, study population. STD Prevention Online. 2017. http://www.stdpreventiononline.org/index.php/resources/detail/2114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Zimbabwe STI Aetiology Study Group. The Aetiology of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Zimbabwe - Study Protocol. STD Prevention Online. 2014. http://www.stdpreventiononline.org/index.php/resources/detail/2039. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mungati M, Mugurungi O, Machiha A, et al. Performance of GeneXpert ® CT/NG in the diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis among men and women with genital discharge syndrome in Zimbabwe. 2015. World STI and HIV Congress, Brisbane Australia https://www.eiseverywhere.com/file_uploads/2bf18fa876f43162bf3cb3f2bf7cd3aa_KeesReitmeijer_P09.21.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chirenje ZM, Gundacker HM, Richardson B, et al. Risk Factors for Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Women in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Chemoprevention Trial: VOICE (MTN-003). Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(3):135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guffey MB, Richardson B, Husnik M, et al. HPTN 035 phase II/IIb randomised safety and effectiveness study of the vaginal microbicides BufferGel and 0.5% PRO 2000 for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in women. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(5):363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malhotra M, Bala M, Muralidhar S, Kunger N, Puri P. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and its association with other sexually transmitted infections in a tertiary care center in North India. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS. 2008;29:82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pépin J, Labbé AC, Khonde N, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium: an organism commonly associated with cervicitis among west African sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(1):67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomih-Alakija A, Ting J, Mugo N, et al. Clinical characteristics associated with Mycoplasma genitalium among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(10):3660–3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandepitte J, Muller E, Bukenya J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium infection among female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(2):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: yet another challenging STI. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):795–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregson S, Gonese E, Hallett TB, et al. HIV decline in Zimbabwe due to reductions in risky sex? Evidence from a comprehensive epidemiological review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(5):1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClelland RS, Sangare L, Hassan WM, et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(5):698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, Ramasamy J. Utility of syndromic approach in management of sexually transmitted infections: public health perspective. Journal of Coastal Life Medicine. 2014;2(7–13). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam N, Chamot E, Vermund SH, Streatfield K, Kristensen S. Partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murtagh M The point-of-care diagnostic landscape for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2016. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/rtis/diagnostic_landscape_2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organization WH. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. 2015; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186275/1/9789241509565_eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed]

- 36.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Nugent RP, Gibbs RS. Characteristics of three vaginal flora patterns assessed by gram stain among pregnant women. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]